Chapter 6

Situational Awareness

For want of a shoe the horse was lost. For want of a horse the rider was lost. For want of a rider the message was lost. For want of a message the battle was lost.

And all for want of a nail.

Unknown

Situational awareness is being aware of what is going on around us. We use it to orient ourselves, and it is a key ingredient of the decision-making process. To gain good situational awareness we need to understand the current conditions and capabilities in our ecosystem. Much as John Boyd predicted in his work on the OODA loop, how well we construct this awareness determines how quickly and accurately we can make decisions.

While information availability and observability is an important ingredient in creating situational awareness, there are other factors that are even more crucial in ensuring its accuracy. These span everything from our past experiences, relevant concepts that we were taught, and what we perceive as the purpose or outcome we are pursuing. Unbeknownst to many of us, situational awareness is also heavily influenced by various cultural elements we have been exposed to at home and work, as well as other habits and biases we have acquired over time. Together these not only shape how relevant we consider the information to what we are trying to achieve but can even interfere with our ability to notice it at all.

The topic of how we build and shape our situational awareness is deep enough to warrant its own book. This chapter is merely an introduction to these factors to help you spot important patterns that can negatively affect any decisions you and others in your team make. At the end of this chapter there are some tips that not only will help improve your situational awareness, but also strengthen the efficacy of other practices in this book.

Making Sense of Our Ecosystem

Gathering and assembling the information we need to build the situational awareness necessary to make accurate decisions can be surprisingly difficult and prone to mistakes. We have to identify what information is available to us. We then need to determine what elements are relevant, as well as whether what we have is both sufficient and accurate enough for our purposes. Then we need to figure out how best to access and understand it.

Despite being one of the largest and most powerful in the animal kingdom, the human brain struggles to reliably and accurately find, sort, and process all the information we need to make decisions. In fact, there is an abundance of research that suggests it is surprisingly easy to overwhelm the human brain. For instance, according to the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), at least 70 percent of commercial aircraft accidents and 88 percent of general aviation fatal accidents are attributed to human error primarily caused by the stress of deficient cockpit design.1 Since the late 1960s, research performed by cockpit designers found that too many signals can actually make it harder for us to find the crucial information we need. Cockpits with too many gauges and indicators increased the stress levels of even the most experienced pilots, causing them to make far more mistakes.2 Even today, pilots describe the experience of learning cockpit automation systems as “drinking from a fire hose.”3

1. US Department of Transportation Research and Special Programs Administration. (1989). Cockpit Human Factors Research Requirements.

2. Wiener, E.L., & Nagel, D.C. (1988). Human Factors in Aviation. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press.

3. BASI. (1999). Advanced Technology Safety Survey Report.

To overcome this limitation, our brains create clever shortcuts that filter and pre-process elements in our surroundings in order to lighten the load. We see these shortcuts in action when we effortlessly perform relatively complex tasks without thinking, like riding a bicycle or playing a favorite video game. These mechanisms are why experience can often lead to faster and more accurate decision making.

Why it is important to know about these shortcuts is that they come with some significant shortcomings. For one, they are far from perfect, and in their rapid handiness can themselves damage your decision-making abilities. Some of the more innocent side effects can be seen with our brains’ over-eagerness to pattern match. We might see familiar objects in cloud shapes and ink blots that aren’t really there. Unfortunately, this eagerness can also cause us to see nonexistent patterns in more consequential circumstances that can lead us to chase problems that are not there. We might, for instance, connect the coincidence of a service failure with activities being performed in a completely unrelated part of the ecosystem, leading to a large waste of time troubleshooting with nothing to show for it.

More problematically, our brains use these same shortcuts to filter out information that they deem superfluous to the task at hand. When our mental shortcut is flawed or our understanding of the situation is inaccurate, these same mechanisms can filter out the very information that we might need, causing us to completely miss the most obvious of facts even when they are jumping around right before our eyes.

This filtering problem was demonstrated many years ago in a short video called “Selective Attention Test,” with the results later being published in a book called The Invisible Gorilla.4 It depicted six people, three with black shirts and three with white ones, passing a basketball around in a hallway. The viewer was challenged to count how many passes were made between people wearing white shirts. During the 80-second video a guy in a gorilla suit strolled out into the middle of the action, faced the camera, thumped his chest, and then wandered off. Even though the gorilla was on screen for a whole nine seconds, over half of the people who watch it are so focused on counting the passes that they miss the gorilla entirely.

4. http://www.theinvisiblegorilla.com

Figure 6.1

“What gorilla?”

We have all at one point or another been convinced something must be happening that wasn’t, all while missing the proverbial gorillas in our midst. They can come in the form of a faulty piece of code in a place we do not expect, a misconfiguration that detrimentally affected some dependency we missed, or even a misalignment between people that is wreaking havoc on our environment.

To improve our situational awareness, we need to first understand how our brain creates and maintains these mental shortcuts. Doing so can help us devise ways to avoid the shortcomings that can get in the way of accurately making sense of our ecosystem.

To start this journey, let’s examine the two most important of these mental shortcuts, the mental model and cognitive bias. This will help us better understand how they work, how they go awry, and how we can catch when they fail us.

The Mental Model

Figure 6.2

The mental model.

A mental model is a pattern of predictable qualities and behaviors we have learned to expect when we encounter particular items and conditions in our ecosystem. Some are as simple as knowing that a rubber ball and an egg will act differently when dropped from a height, or that people will usually stop at a red traffic signal. Others can be more complex, like the behavior and likely output of a service journey when given a certain request type. Together they shape how we perceive the world and the probability of certain conditions occurring that we can use to make decisions and solve problems.

Mental models are typically constructed from data points we collect through a combination of first-hand experience and information gleaned from people, books, and other sources. These same data points become clues that we use to identify, verify, or predict ecosystem events. The more relevant data points we collect about a given situation, and the more first-hand experience we have encountering those data points, the greater the depth of situational awareness we can gain from them. Over time, continual contact with those data points not only dramatically reduces the cognitive load necessary to identify a given situation but also increases decision-making speed to become instantaneous and intuitive.

Gary Klein found when researching firefighters5 that those with such tacit knowledge and expertise were able to decide and act quickly on important but minute signals others likely would easily miss. In one example a firefighter commander fighting what appeared to be a small kitchen fire in a house sensed that something was wrong when the temperature of the room did not match what he expected. In the unease, he immediately ordered his entire team to leave. Just as the last person left the building the floor collapsed. Had the men been in the house they would have plunged into the burning basement.6

5. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254088491_Rapid_Decision_Making_on_the_Fire_Ground_The_Original_Study_Plus_a_Postscript

6. https://www.fastcompany.com/40456/whats-your-intuition

In the previous example, the commander compared his mental model of a small fire (lower ambient room heat) with the data points he was observing (unusually high ambient room heat). The mismatch made him doubt not the accuracy of his mental model but whether his understanding of the situation was correct. This unease caused him to order his team to leave so that he could reassess the situation.

The Problems with Mental Models

When they are well constructed, mental models are an incredibly useful mechanism. The challenge is that their accuracy depends heavily upon the number, quality, and reliability of the data points used to construct them. Having too few can be just as dangerous as relying upon many irrelevant or unreliable ones. Take the example of the fire commander in the previous section. He would have received just as little situational awareness benefit from only knowing the fire was in a kitchen and was small as he would have knowing that the kitchen walls were painted blue or that the pots and pans in the kitchen had been wedding presents.

The mechanisms used to collect data also play an important role in how accurately our mental model is shaped. The most dangerous are those that are considered more trustworthy than they actually are.

One good example of this comes from the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant accident in March 1979. A series of minor faults led to a pressure relief value in the reactor cooling system becoming stuck, allowing cooling water levels in the reactor core to drop. A fault in an instrument in the control room led the plant staff to mistakenly believe that everything was okay. With no way to measure water levels in the reactor core, operators failed to realize that the plant was experiencing a loss-of-coolant accident even as alarms rang out that the core was overheating.7 This resulted in a partial meltdown of the Unit 2 reactor, with radiation contaminating the containment building and the release of steam containing about 1 millirem of radiation, or about one-sixth the radiation exposure of a chest X-ray.

7. https://www.nrc.gov/reading-rm/doc-collections/fact-sheets/3mile-isle.html

Figure 6.3

“Scary” nuclear power cooling towers.

Interestingly, the Three Mile Island accident created another set of flawed mental models. This time it was with the public. Despite the fact that the accident caused nearly no negative health effects, the public became convinced that nuclear power was far more dangerous than more conventional power sources such as coal. This is despite the fact that burning coal produces far more in the way of health-damaging toxins into the environment, often including aerosolized radioactive material. As a result, construction of new nuclear power plants fell precipitously while existing plants were pushed to close.

Data Interpretation Issues

Having accurate data sources does not mean that we are completely out of danger. The usefulness of a mental model also hinges on the accuracy of our interpretation of the data we use to construct them. Even when the data is factually correct, there are a lot of factors that can cause us to still misinterpret it in a way that is faulty. Timeliness, coverage, granularity, and suboptimal collection methods can leave us with a poor understanding of the current situation and the events leading up to them, as well as a flawed grasp of the effect of any actions taken.

Interpretation inaccuracy is a big problem in many industries. For instance, virologists long believed that anything larger than 200 nanometers in size could not possibly be a virus. This belief survived as techniques used to find viruses removed anything larger. It was only through some later filtering mistakes that they discovered the existence of entire classes of giant megaviruses, many with unique features that have altered many other ideas about viruses that researchers once believed. Similarly, many IT organizations suffer from monitoring that can be both too sensitive, producing so many false-positives that actual problems are lost in the noise, and not sensitive enough, where faults and race conditions that were not imagined are missed completely.

Mental Model Resilience

The longer a mental model is held, the more it begins to form the core of our understanding of the world. This makes it increasingly resilient. Such resiliency can be very useful for responding quickly and expertly to situations where the model is genuinely applicable but some of the details might differ in relatively unimportant ways from experiences in the past. For instance, driving a different brand or model of car is typically not that big of a deal if you are an experienced driver and the layout of its main controls are roughly where your mental model would expect them to be.

Unfortunately, when your mental model is flawed, an approach that is far superior is found, or your ecosystem has changed so much as to render your mental model obsolete, this same resiliency can still heavily influence your decision making. Old approaches can “just feel right” even when there is ample evidence of the problems they cause.

Such misalignments are also stressful for those who face them. To seek relief, those facing them can become good at explaining away any experiences that conflict with established ideas. At first it will be brushed away as a unique event or a stroke of bad luck. If the situation continues to deteriorate, they may even create an elaborate conspiracy theory to explain it. For some the stress can become so great as to cause cognitive dissonance. Such holding of two opposing ideas as simultaneously true inevitably causes considerable damages to the inflicted individual’s decision efficacy.

To replace old models with new and more appropriate ones, people need time and support for them to properly embed. This is often hard in the modern workplace and is why culture changes and process transformations struggle to take hold. Many industries and occupations even have their own ingrained and dysfunctional models, making it even tougher to support such improvements. Without time and help to fix these misalignments, our brains will sometimes cause us to double down on the broken model. Our views harden further and we shut out or belittle any conflicts we encounter.

Cognitive Bias

Cognitive biases are a much deeper and often cruder form of mental model. They exist at a subconscious level, relying upon subtle environmental triggers that predispose us to filter, process, and make decisions quickly with little information input or analysis. Some arise from subtle cultural characteristics such as the perception of time and communication styles, or the level of tolerance for uncertainty and failure. However, the vast majority of biases are more innate and culturally independent. It is these that so often go unnoticed, affecting our ability to make sensible decisions.

There are many cognitive biases that plague us all. Table 6.1 includes a number of the more serious ones that I regularly encounter in service delivery environments.

Table 6.1

Common Cognitive Biases

Bias | Description | Impact |

|---|---|---|

Confirmation bias | Tendency to pay attention to information that confirms existing beliefs, ignoring anything that does not | Inability to listen to opposing views, and the likelihood that people on two sides of an issue can listen to the same story and walk away with different interpretations |

Hindsight bias | Tendency to see past events as more obvious and predictable than they are | Overestimate ability to predict and handle events, leading to taking unwise risks |

Anchoring bias | Tendency to be overly influenced by the first piece of information received for decision making and using it as the baseline for making comparisons | Inability to fully consider other information leading to suboptimal decision making |

Sunk cost fallacy | Justifying increased investment in a decision or endeavor because time, money, or effort has already been invested into it, regardless of whether the cumulative costs outweigh the benefits | Overinvesting resources that could be better spent elsewhere |

Optimism bias | Tendency to underestimate the likelihood of failure scenarios | Poor preparation and defense against failure |

Automation bias | Depending excessively on automated decision-making and support systems, ignoring contradictory information found without automation even when it is clearly correct | Increased risk from bad decision making, situational awareness, and learned carelessness (e.g., driving into a lake because Google Maps told you to) |

This list is far from complete, and you will almost certainly encounter other cognitive biases in your own organization. What is important is ensuring that you and the rest of your team are aware of their existence and their effects, keeping a lookout for them as part of your decision-making process. Such awareness is itself crucial before taking the next step of finding ways to gain better situational awareness.

Gaining Better Situational Awareness

Now that you are aware of the failings of the shortcuts your brain uses to reduce cognitive load, you can begin the process to construct mechanisms to catch them in action, check their accuracy, and make any necessary course corrections to gain better situational awareness and improve your decision making.

The first step in any improvement activity is to start by getting a good idea of the current state. Fortunately, there are common patterns that every person and organization follows to organize and manage the information necessary for making decisions. These fall into the following categories:

Framing: The purpose or intent that staff use to perform their tasks and responsibilities. Any alignment gaps between this framing and customer target outcomes can lead to errant mental models and information filtering.

Information flow: The timeliness, quality, accuracy, coverage, and consistency of the information used for decision making as it flows across the organization. How is it used? Who uses it? Is information altered or transformed, and if so, why?

Analysis and improvement: The mechanisms used to track situational awareness and decision quality and identify and rectify the root causes of any problems that occur. Who performs these activities, how often do they occur, and what are the criteria for triggering an analysis and improvement?

Let’s take a look at each of these to understand what they are, why they matter, how they can become compromised or rendered ineffective, and how they can be improved.

Framing

Figure 6.4

Framing cannot be done haphazardly.

Every activity you perform, responsibility you have, and decision you make has a purpose no matter how inconsequential. This purpose is your guide to know whether you are on track to successfully complete it, and the way that it is framed can heavily influence what information and mental models you use along the way.

Framing can take a number of forms, many that can interact and even interfere with one another. Some are the acceptance criteria of an individual task. There are also the overall objectives of the project or delivery itself. Then there are team and role responsibilities and priorities, as well as the performance evaluation measures used for raises, promotions, and bonuses.

Ideally, all of this framing should add context that better aligns work to deliver the target outcomes desired by the customer. However, it is extremely easy for gaps and misalignments to form when there are so many layers that people have to contend with.

Finding and Fixing Framing Problems

For better or worse, organizational framing problems tend to follow familiar patterns. Recognizing these patterns can help you find the misalignments in your organization that need to be fixed. Each of these patterns is described next in turn. I have included some details about how they often manifest themselves, as well as some ways to overcome them.

Pattern 1: Customer Engagement

Aligning work to a customer’s desired outcomes is never easy. Customers aren’t always willing to share, and even when they do it can be difficult to understand their desired outcomes in the same context they were derived. It also doesn’t help that many delivery teams never get an opportunity to meet and build a relationship where that information and context can flow directly.

Few organizations do much to help matters. Many use product and project management, Sales, and even managers to effectively broker information between customers and those responsible for doing the actual delivery work. This is usually done under the flawed belief that intermediating can maintain better control over information flow, and thereby the work performed, to keep technical staff focused on what are deemed as the correct priorities while not unnecessarily scaring customers with out-of-context details of service delivery processes.

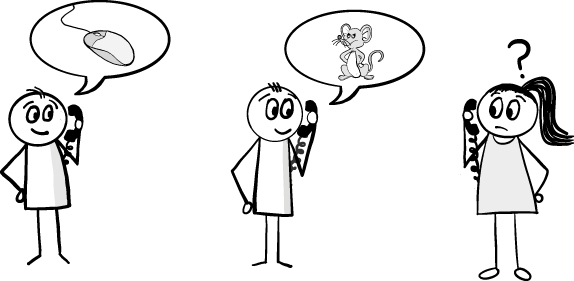

Such an “air gap” in the information flow creates a lot of opportunities for information loss and misframing. It makes it difficult to check and correct errant assumptions, creating awareness drift that can result in dangerously flawed mental models, just like the children’s game of telephone where information increasingly gets lost or is distorted the longer the chain grows.

Figure 6.5

Information can become scrambled as it passes between people.

While the best way to solve this awareness drift is to actually try to engage with the customer, jumping straight into a conversation with one is not always possible or advisable. Even if you do, it is likely that it will take time and patience to dispel any flawed assumptions that you and others in your team have collected over time before you can start to really see what is going on.

When beginning the journey to understand the customer, one of the best places to begin is to closely examine the ways they interact with your ecosystem. First, evaluate the services the customer uses directly. Capture and analyze their experience to spot potential problems and opportunities. This evaluation has the advantage of being both more familiar and accessible than an actual customer, and can also facilitate any conversation in cases where you do eventually have an opportunity to interact with the customer. It also has the benefit of revealing aspects of customer interactions that they might not realize themselves or might be unwilling to freely disclose.

Customers inevitably leave a long trail of clues behind. Much of this trail is discussed in Chapter 11, “Instrumentation,” and includes everything from logging and service telemetry to monitoring transactions and service performance, as well as tracing customer and service journeys.

Customers also engage and impact with your organization directly in ways that can provide additional clues about both their needs and how your organization handles them. Sales, Customer Engagement, and Support functions can help provide a bridge to the customer, as well as some insight into their desires and concerns. You might discover places where service properties are misunderstood. I have prevented many potentially disastrous engagements by finding and correcting such misunderstandings in both the sales and contract negotiation phases, as well as in digging into the details behind customer complaints and feature requests.

I also, as discussed in Chapter 11, “go to the gemba” or where the work is being performed to see how customer interactions affect delivery and service supportability. Sometimes customers are more than happy to make adjustments to their own demands if they realize they are degrading the delivery or supportability of other functionality that is far more important to them. Capturing this information allows you to have more factual conversations that can help you better help them reach their target outcomes.

Pattern 2: Output Metrics

Measuring an output is generally easier than measuring an outcome. Outputs are also far less ambiguous. This is a big part of why managers have a natural preference to evaluate individual and team performance based upon meeting delivered output targets.

The problem is that customers measure their own success not on the outputs you generate but the outcomes they achieve. Customers do not care if your service has 99.999 percent uptime or extra features if none of it ensures that they are able to use it effectively to meet their needs at the very moment they need it. I have encountered this issue repeatedly, especially on trading floors where the customer can be extremely vocal. Such mismatch between targets and making sure the customer has what they need when they need it can be costly both financially and with customer trust.

While it is true that outputs have the potential to contribute to a customer achieving a customer outcome, having staff focus centered on delivering the output only guarantees that the output will be achieved, not the outcome. Information that is not needed for delivering the output can easily be missed, ignored, or even buried if it might detract from delivering it. This is especially true if delivering the metric is tied to performance evaluation metrics.

I actively seek out and try to eliminate output-based metrics whenever possible. In their place I work with individuals and teams to construct metrics that are meaningful for helping customers attain their target outcomes. One of the best places to start is to look at framing the acceptance criteria for tasks and responsibilities to help the customer reach them, and then search for ways that the contribution can be measured. For instance, in the case of uptime I look to measure the negative impacts toward the customer reaching their outcomes due to service loss, errors, and latency. For features, I look at how the feature fits into the customer journey, how often is it used, how easy is it for the customer to use, and how valuable is its usage to helping the customer achieve their target outcomes. All of this helps reorient you and your staff to reframe how you view the ecosystem around you and the decisions you make within it.

Pattern 3: Locally Focused Metrics

Metrics that are tightly framed around team or person-centric activities are another common distortion in organizations. Besides not being framed around customer outcomes, the tight focus often causes teams to lose sight of the rest of the organization as well.

There are a multitude of ways that this occurs in DevOps organizations. Sole focus on your own tasks can cause you to have long-lived branches with little thought of merging and integration issues that will likely crop up later. When specialty teams exist, there is a risk that they can concentrate only on their own areas rather than on those that achieve the target outcomes of the customer. Sometimes alignment is so poor that other teams put in workarounds that can make overall situational awareness worse.

Information flow also breaks down and becomes distorted. At best local framing results in ignoring any information immediately outside that tight scope, even if it is likely beneficial to another group. When the measures are used to compare and rate teams against each other, it not only discourages sharing and collaboration, it leads to information becoming a currency to hoard, hide, or selectively disclose to attain an advantage over others. The end result is information distortion and friction that degrade decision making throughout the organization.

I actively seek out locally focused metrics for removal whenever I can. In order to reverse the damage they cause, I often create performance metrics centered on helping others in the organization be successful. These may be other teammates, adjacent teams, or other teams delivering solutions across the same customer journey. I find that doing so helps refocus people to think about others, the whole organization, and ultimately the needs of the customer.

Information Flow

There is little chance that all information in an ecosystem can be made readily available with sufficient accuracy to everyone on demand at any time. Even if it were possible, it would likely be overwhelming. While accurate framing and valid mental models can narrow the scope of information needed, alone they provide little insight into the timeliness, quality, accuracy, coverage, and consistency that information must have to ensure you have sufficient situational awareness to make accurate decisions.

This is where the dynamics of your delivery ecosystem come in.

Why Ecosystem Dynamics Matter

As you learned in Chapter 5, “Risk,” the dynamics of your operating ecosystem do play a fundamental role in determining which information characteristics are important for decision making. The reason for this is that the rate, predictability, and cause-and-effect of ecosystem change directly correlate to how often and to what extent mental models need to be checked to maintain an accurate awareness model for decision making.

In other words, it doesn’t take much feedback to get to reach a “good enough” decision to reach a desired outcome in a relatively predictable and easily understood environment. Under such conditions you only need enough information to identify what mental models to use and when to use them as there is little risk of any dramatic or unforeseen change invalidating their accuracy.

As the dynamics of your environment increase and become more unpredictable and undiscoverable (or “unstructured,” in the language of Cynefin, discussed in Chapter 5, “Risk”), the accuracy of your mental models begins to break down and the thresholds for what quality, coverage, type, and timeliness of feedback needed to both catch and correct any mental model problems as well as reach a “good enough” decision grow considerably.

To help to understand this better, let’s consider the dynamism of the ecosystem of your commute to work. There is little need for lots of rapid, high-quality feedback if your commute consists of nothing more than logging into work from home on your computer. The process is well known and is unlikely to change much without considerable warning.

There is a little more variability if your commute consists of catching a train to the office. You will need to know train availability, departure and arrival times, possibly which platform the train will depart from, and whether you need to obtain a new ticket. While this is certainly more information than is needed when you work from home, most of it only augments existing mental models. Inaccuracies are not only rarely fatal, they can usually be easily corrected for along the way with at worst only mild inconveniences.

Figure 6.6

Commuting by train has low information flow requirements.

Commuting to work by driving a car, however, is a completely different story. Driving requires operating in a very dynamic ecosystem. Everything from traffic and traffic controls, other drivers, pedestrians and animals, weather, road conditions, and even unexpected objects can dramatically change a situation, and with it appropriateness of any decision, instantly. I have personally had to dodge to avoid everything from chickens and moose running around on the roadway, a barbeque flying off the car ahead, to flash flooding and police chases. With such dynamism, feedback needs to be instant, accurate, and with enough coverage to adjust for any new developments that if missed can detrimentally affect achieving the desired outcome of getting to work alive without injuring yourself or others. Unlike in the other two scenarios, mental models are more geared for helping facilitate information gathering and decision prioritization than acting as a step-by-step recipe for executing the activity to outcome.

Figure 6.7

Sam needs to stay situationally aware of his surroundings in order to safely commute by car.

Figuring out what characteristics and information you need takes knowing the dynamics of the delivery ecosystem. As you will see, you will need to consider the mental model friction and cognitive biases of people within your delivery ecosystem, what outcomes you are targeting, as well as the risk profile you are willing to accept to reach them.

Meeting Your Information Flow Needs

To be effective, each individual has different information needs. Some people are quick to spot a meaningful condition or discrepancy and investigate. Others can easily miss or happily ignore anything that does not precisely fit the expectations of their mental models. Most people fall somewhere in the middle of this spectrum, catching some information, missing other information, and force-fitting everything else in ways that filter or distort their understanding of what is actually happening.

Finding these variations can be challenging. This is why whenever I begin in an organization I find a variety of “tracers” (which are little more than information elements, tasks, and events) to effectively trace what information characteristics are used across different people and teams as information flows through the organization. A tracer is often little more than a set of information elements, tasks, or events that forms part of a decision and delivery item that is important to meet customer needs. Some examples include a deployment, an incident, a standard request, and work planning.

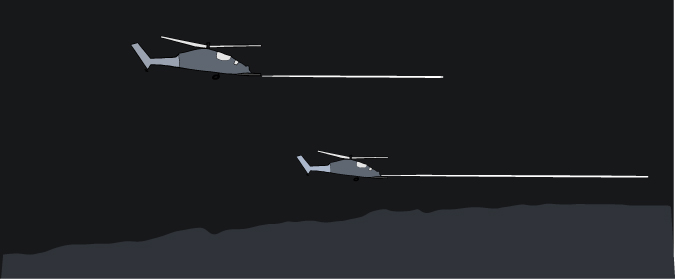

Figure 6.8

Think of “tracers” like military tracer fire. It is to see that you understand and adjust to conditions to better “hit your target.”

I find that tracers can help expose the level of predictability and preparedness for events, their likely range and rate, how and where they enter and are handled, how adequately they are managed and completed, and how this lifecycle impacts customers. Tracers also uncover the sources and consumers of the information needed for decision making, as well as its flow and how well its characteristics match the needs of decision makers. Together, all of this should expose efficacy gaps that can be investigated more deeply so that any problems and associated risks can be reduced or eliminated.

Examining tracers in an ecosystem that you have been long a part of can be difficult, if nothing more than because you have to contend with your own flawed mental models and cognitive biases along the way. Fortunately, there are some common patterns for information flow problems that you can look for that can help you get started.

Pattern 1: Information Transmission Mismatches

Figure 6.9

Despite Suzy’s plan to add text messaging functionality to her phone, she still struggled to get the information she needed.

Transmitting information in a way that it is immediately understood with the correct context in an actionable way at the right time is surprisingly difficult. As we saw with the Three Mile Island incident, this is especially challenging if the information needs to invalidate any potential mental models in the process of trying to inform.

One of the most common problems in transmitting information comes from relying upon mechanisms that do not reliably possess characteristics that can get information to the people who need it in a way that can pierce through any flawed mental model to be employed to guide key decisions at the right time. Most of the time this occurs because people haven’t thought clearly about what characteristics are important. Instead, they rely upon either whatever transmission methods are most readily available or whatever others typically use without giving any thought to their suitability.

Some common mismatches include the following:

Monitoring systems that are configured to catch and relay events rather than relay the current conditions to provide effective decision-making support. As a result, information must be sifted out of noise and then cobbled together by staff using their past experiences, available documentation, and guesswork to find out what is going on. This high-risk, high-friction approach can fail spectacularly, as it did with Knight Capital when cryptic alerts about a critical misconfiguration that ultimately sank the company were missed, as they were sent by email in the early hours of the day.

Sourcing data from systems to drive decisions without regard to its accuracy, context when it was generated, and its relevancy to other data it is processed and compared with. Such mismatches are common in AI/ML environments that must rely upon data from sources that were not originally designed with such purposes in mind. This might be harmless when it results in poorly targeted ads, but can be dangerous or even fatal when it involves medical or environmental data.

The use of lengthy requirements documents, poorly laid-out user story tasks, long email chains, and numerous meetings to communicate task and role objectives, dependencies, and anti-goals.8 Unlike what was detailed in Chapter 3, “Mission Command,” little is done to ensure that there is enough information regarding target outcomes, the current state, potential risks, or which risks are tolerable in pursuing those outcomes. Instead, most communication focuses primarily on what to deliver and ignores what outcome it is trying to deliver and why it is desired. This results in both frustration and the likelihood of unknowingly delivering without sufficient context of ecosystem dynamics and not achieving the target outcomes.

8. Anti-goals are events, situations, or outcomes that you want to avoid.

The use of methods for cross-team and cross-organization communication that do not consider how much or at what speed and accuracy context needs to be communicated, nor sufficiently promote camaraderie and collaboration. This has become an especially pressing problem in the distributed working environment that so many of us now find ourselves in. Emails, task tracking tickets, chat rooms, and video meetings each are limited in their fidelity for communicating contextual information. They also struggle to flag disconnects and flawed mental models. This all results in a fracturing of ecosystem understanding, “us-vs.-them” conflicts, and siloed thinking. All of these make it extremely difficult to correct mental model flaws and effectively deliver target outcomes.

Transmission mismatches are endemic in IT. This is likely because most in the industry tend to think more about convenience, novelty, or following the same approach that others are using than about finding the method best suited for making timely and accurate decisions. However, IT is far from the only industry with such mismatches. I have encountered them in industries spanning from medicine and finance to energy and industrial supply chains. Many industries might not be as willing to use new or novel methods as quickly as IT, but even groups with names like “Business Intelligence” and “Decision Support” often still struggle to think about ensuring that information flows ensure intelligent and supportable decisions.

This is why it is so critical to regularly check the flows in your own ecosystem. Many of the practical methods mentioned in this book, from the Queue Master (Chapter 13) and Service Engineering Lead roles (Chapter 9) to instrumentation (Chapter 11) and the various sync point mechanisms (Chapter 14), are provided to help you and your team on your journey.

Pattern 2: Cultural Disconnects

Figure 6.10

Cultural differences often go far beyond language.

The differences in experiences that individuals, teams, and organizations have affect more than the mental models they hold. They also impact the characteristics and perceived value of the information itself. When experiences are shared within a group, they can become part of common cultural framework that can facilitate intra-group communication of information in the right context.

Just like any other culture, as these shared experiences grow and deepen over time, this framework can expand to include a wide array of jargon, rules, values, and even rituals. While all of this can further streamline group-centric communication, it does have some downsides. One is that shared mental models are even tougher to break than individually held ones. The other is that one group’s communication streamlining can seem like impenetrable or nonsensical gibberish to outsiders.

Such cultural disconnects can create real problems for the information flow necessary to coordinate and align the decisions necessary to deliver the right outcomes.

IT organizations can hold any number of such cultures, each full of its own terminology and priorities. Development teams value the speed of delivering feature functionality or using new interesting technologies, while operational cultures tend to favor stability and risk mitigation. Database teams are interested in schema designs and data integrity, while network teams tend to pay close attention to throughput, resiliency, and security. The differing dispositions and motivations of each team alters what and how information is perceived. Without the right motivation and coordinated objectives, maintaining alignment to a jointly shared outcome can be difficult.

Being aware of these cultural differences can help you find ways to reduce frustration and conflict caused by faults and misalignments in the situational awareness between teams. This can aid in finding and correcting any misperceptions of the target outcome such misalignments may cause. There are a number of ways to do this. One is by building better communication bridges between groups that encourage trust and understanding, as discussed in Chapter 3, “Mission Command.” You can also minimize the number of faults in your assumptions by being clearer about what is going on, as well as use the Mission Command techniques such as backbriefing and increased personal contact in order to improve information flow and catch any misalignments that might form along the way. These can make you and your team better decision makers.

Pattern 3: Lack of Trust

Trust is an underappreciated form of information filter in an organization. Your level of trust is the gauge you use to determine how much you need to protect yourself from the selfish self-interests of a person or organization. The less trust you have the more likely you are going to hide, filter, or distort information that the other party might use for decision making. This has the obvious effect of slowing the flow of information in a way that erodes situational awareness and decision effectiveness.

Trust can be squandered in a number of ways. Rarely is it due to personal or organizational sociopathy. Most of the time the cause starts out as a misunderstanding or mishandling of a situation where a person has been left feeling injured or taken advantage of. In IT, the following are the most common ways this occurs:

Forced commitment: A person or team is forced to accept a commitment made by someone else, often with a careless disregard of its actual feasibility. This could be anything from aggressively set release deadlines to signing up to hard-to-deliver requirements. The crux of the problem is the mismatch between customer expectation and effort. With the commitment made, the customer expects that the risk of failure is lower than it actually is. Not only is the delivery team constantly under a sizeable threat of failure, any herculean efforts made to improve the odds for success go unrecognized.

Unreasonable process inflexibility: A process that is supposed to improve situational awareness actually damages it through its stringent inflexibility and problematic process chains. Rather than working toward what ought to be the desired outcome of the process, people hide details and use political and social pressures to work around the rules and procedures. This, of course, opens up the risk of surprise and further distrust.

Blame-based incident management: Incident management processes look for scapegoats either in the form of people or technology and assign blame rather than finding and eliminating the incident’s root cause. This results in a game of “Incident Theatre” where investigative scope is severely narrowed to the event itself, details are obfuscated or omitted to minimize blame, and improvement steps are limited to either a confined list of identified symptoms or blown out into a list of poorly targeted improvements that are unlikely to tackle the root cause.

The most effective way to avoid losing trust is to build in a culture and supporting mechanisms that actively promote a strong sense of respect between the people in the organization. Respect is what creates a unified sense of purpose, sense of trust, and sense of safety that motivates people to break down barriers to work together to achieve success.

Teams and organizations that foster trust and respect regularly demonstrate the following:

Creating a safe working environment: It is never enjoyable to work in an environment that is unnecessarily stressful. Often stress comes from the technology itself, such as having to handle/debug/develop on top of hazardous software that is poorly designed, overly complex, brittle, tightly coupled, full of defects, difficult/time consuming to build, integrate, and test, or simply was never meant to be used the way others now want to use it. Other times the supporting elements for building and supporting a safe working environment are a major source of stress, such as having unreliable infrastructure or tools that fail for no reason, or tools that are difficult to use or make it difficult to reliably and efficiently deploy, configure, or manage your services. Stress can also be working in an environment full of constant interruptions from noise, meetings, or activities that take away from the effort required to get the job done. Teams need to be allowed to have time actively set aside to identify and remove such stressful elements from their working environment. Doing so not only shows that the organization cares about their well-being, but also helps reduce the noise and stress that reduces situational awareness and decision making.

Fostering a sense of feeling valued and belonging: People who feel they are a key part of what makes the team successful, and not just some interchangeable resource, are far less likely to hide or distort information. Help them take pride in their work by trying to create an atmosphere where they feel they have a part in the successes and accomplishments of the team, organization, and ultimately the customer achieving their target outcomes. One way to do this is by replacing person-specific performance targets with more customer-centric or organization-centric ones. Encourage the team to identify errors and mistakes not as points of blame but signs of some element in the ecosystem that has been found to be unsafe and needs to be improved and made safe. I also encourage teams to get to really know each other and not view others as resources or rivals.

Creating a sense of progress: People can become demotivated and feel that work is less purposeful if they do not feel a sense of progress toward a goal. Establish frequent and regular quality feedback mechanisms that show how much progress is being made toward a set of outcomes or goals. Iterative mechanisms such as daily standups and visual workflow boards help with showing accomplishments. I also use retrospectives and strategic reviews, as covered in Chapter 14, “Cycles and Sync Points,” to have the team reflect on the progress that they have made. This helps people see that there has been progress in improving, as well as can be motivational for finding ways to get even better.

Analysis and Improvement

With so many ways for our situational awareness to become fractured and distorted, it makes sense to have some means within your team to regularly check for, correct, and proactively look to prevent the future development of any flaws that might damage service delivery.

Most teams do have some means for checking and correcting for context and alignment issues. They usually take the form of checkpoint and review meetings geared for verifying that everyone has the same general understanding of a given situation and what needs to be done to move forward, as well as checklists to help ensure that steps are not accidentally missed along the way.

While such a strategy can work to catch and address misalignment and understanding mistakes, it counts on having everyone fully participating and paying attention. This is not a safe assumption to make in the best of times, and is one that usually fails spectacularly when people are under stress. It also does little to tell us the root causes that might be creating awareness gaps to form, let alone address them so that they no longer persist to cause damage again in the future.

One of the best ways to fix this is to recraft the way you and your team look at mistakes and failures. Rather than thinking of them as the fault of a person or misbehaving component, approach them as a faultless situational awareness failure. Finding why situational awareness was lost, whether it was from a flawed mental model of a situation, a misframing, or faulty information flow, can help you uncover why it occurred and put in mechanisms to reduce the chances it occurs in the future.

Such recrafting has an added benefit in that it makes it far easier to avoid blame. The mechanisms that support individual and team situational awareness have fallen short and need to be improved to ensure success. This reduces the risk of finger-pointing and other behaviors that do little more than further erode team effectiveness.

It is also important to proactively search for potential hazards that can cause situational awareness to degrade before they have a chance to harm. Many of the techniques covered in this book, whether in the form of roles like Queue Master and Service Engineering Lead, sync points like retrospectives and strategic reviews, work alignment mechanisms like workflow boards and backbriefings, or instrumentation and automation approaches, are designed with elements that try to expose any drift between the way that people understand their surroundings and their actual state.

Another mechanism that I regularly use is to war-game various scenarios with the team. To do this I will ask about a particular service, interaction, flow, or some other element to see how they construct and update their situational awareness. Seeing how much people rely upon their mental models, how strong those mental models are, and what information they feel can help guide them to the right decisions and can help uncover gaps that can be quickly rectified. Often gaps can be found in simple roundtable discussions, though sometimes these are followed up with actual or simulated scenarios to double-check that details are correct.

Summary

Our situational awareness is how we understand our ecosystem and orient ourselves to make sensible decisions within it to reach our target outcomes. There are a lot of ways that our situational awareness can go awry, from flawed mental models and poor communication methods to cultural differences, badly calibrated work evaluation approaches, unclear or locally focused objectives, to a lack of trust and sense of progress. Understanding these dynamics within your ecosystem and constantly improving them can help improve the sorts of misalignments and disappointments that damage delivering the right services optimally.