7. Transportation Systems

As the saying goes, “A chain is only as strong as its weakest link.” In the case of the supply chain, the link is your transportation system, and its strength can mean the difference between the success and failure of your business.

To be successful, the transportation system used to connect your supply chain must be managed and controlled properly, with complete visibility and great communication between partners. Transportation and logistics costs (mainly warehouse operations, which are covered in the next chapter) can account for as much as 7% to 14% of sales depending on the industry you are in. Transportation costs alone comprise the vast majority of this expense for most companies. Best-in-class companies have transportation and logistics related costs in a range of 4% to 7% depending on industry sector. So, it’s not hard to see both operationally and financially important transportation is to a successful business.

There are also many professional career opportunities in the transportation field, both in corporate goods and services organizations (usually in the transportation, traffic, or logistics departments) as well as in transportation companies. They can range from corporate to operations and even sales. Besides the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (CSCMP) organization mentioned previously, there are many others, such as AST&L (American Society for Transportation & Logistics; www.astl.org) and SOLE (International Society for Logistics; www.sole.org).

As a first step, it is important to understand background on the history of transportation systems in the United States, followed by a discussion of the various characteristics of transportation types and modes, along with their cost elements, rate structures, and some of the necessary documentation.

Brief History of Transportation Systems in America

In the late 18th century, overland transportation was primarily by horse, and water and river transportation was primarily by sailing vessel.

As a result of the distances between cities and the cost to maintain roads, many highways in the late 18th century and early 19th century were actually privately maintained turnpikes. Other highways were largely dirt roads and impassable by wagon for at least some of the year. Economic expansion in the late 18th century to early 19th century was the impetus for the building of canals to move goods rapidly to market. One of the most successful examples was the Erie Canal.

As a result, access to water transportation tended to shape the geography of early settlements and boundaries.

Development of the midwestern and southern states located on or near Mississippi River system was accelerated by the introduction of steamboats on these rivers in the early 19th century.

The rapid expansion railroad transportation in the 1830s to 1860s ended the canal boom and provided a timely, scheduled year-round mode of transportation. Railroads rapidly spread to connect states by the mid-1800s. As the United States industrialized after the Civil War, and with the creation of the transcontinental rail system in the 1860s, railroads expanded rapidly across the United States to serve industries and the growing cities.

The passage of the Act to Regulate Interstate Commerce, in 1887, allowed the federal government to become more active in protecting the public interest. It established the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), which had broad regulatory power in the area of transportation, which lasted until 1980. During this period, the federal and state governments determined who could provide transportation services and the price they could charge for their services.

The invention of the automobile started the decline of passenger railroads and increased mobility in the United States, the latter adding to economic output.

Freight railroads also began to decline as motor freight captured a significant portion of the business. This loss of business, along with the highly regulated environment with its restricted pricing power, forced many railroads into bankruptcy and resulted in the nationalization of several large eastern carriers into the Consolidated Rail Corporation (Conrail).

Air cargo deregulation was signed into law a year prior to the passage of the Air Deregulation Act in 1978, which was directed at passenger airlines. Deregulation in trucking and railroads became official with the passage of the Motor Carrier Act of 1980 (MC 80) and the Staggers Rail Act (Staggers Act), which created a regulatory environment favorable to the business economics of the railroad and trucking industries.

With globalization starting in the 1980s, air cargo transport, a vital component of many international logistics networks commonly used for perishables and premium express shipments, grew rapidly.

In the 1990s, the increase in foreign trade and intermodal ocean container shipping led to a resurgence of freight railroads, which today have consolidated into two eastern and two western private transportation networks: Union Pacific and BNSF in the west, and CSX and Norfolk Southern in the east. The Canadian National Railway acquired the Illinois Central route down the Mississippi River Valley.

Transportation Cost Structure and Modes

The primary modes of transportation are truck/motor carrier, rail, air, water, intermodal transportation, and pipeline. Before getting into specifics, it is helpful to understand the cost structure for transportation because a primary source of difference between modes is operating cost and flexibility.

Transportation Costs

Transportation costs are both fixed and variable. The fixed-cost component refers to costs that do not change with the volume moved, such as buildings, equipment, and land. Variable costs, in contrast, are costs that do change with the volume moved, such as fuel, maintenance, and wages.

The areas where these costs occur in transportation are as follows: 1) the ways (that is, road, air, and water), 2) terminals (including administration) where goods are loaded and unloaded, and 3) the vehicles themselves used to haul the freight.

Ways

The ways are the land, water, road, space, and so on over which goods are moved and may be owned by the operator (railroad tracks), run by the government (roads, canals), or made by Mother Nature (ocean).

Terminals

The terminals are used to sort, load and unload goods, connect between line-haul and local deliveries or between different modes or carriers as well as dispatching (that is, to monitor the delivery of freight over long distances and coordinate delivery pickup and drop-off schedules), maintenance, and administration.

Vehicles

The vehicles themselves are either owned or leased by the transportation companies and have a mix of fixed (for example, vehicle capital investment) and variable (for example, fuel, maintenance, and labor) operating costs.

Modes

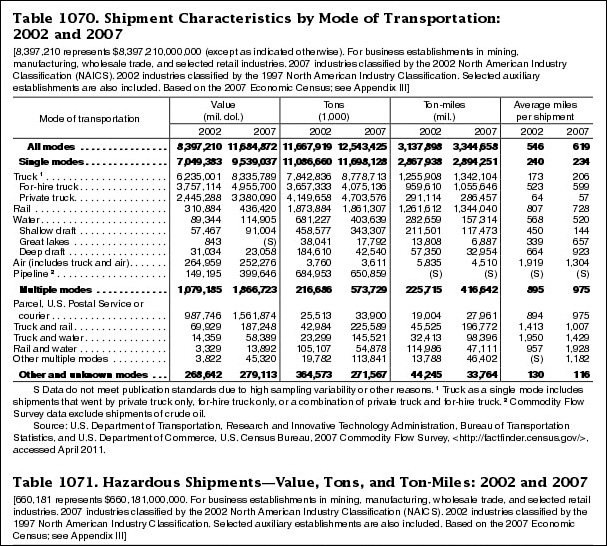

In general terms, trucks carry the greatest dollar volume of freight in the United States (71%) because they tend to haul higher-value consumer goods. Rail, which tends to haul lower-value commodity items longer distances, matches motor carriers in terms of ton-miles (39% each). Not surprisingly, air transport has by far the longest average miles per shipment, at 1,304, followed by rail (728) and then water (520) (U.S. Department of Transportation, 2007; see Figure 7.1).

The following subsections cover each mode of transport in more detail.

Rail

Rail is the slowest, least flexible, yet lowest-cost mode of transportation. So, it is typically used to transport bulky commodities over long distances. Because rail carriers must provide own ways, they are actually natural monopolies, but still must provide their own terminals and vehicles, resulting in a large capital investment and high volumes required to operate a railroad. As a result, they tend to have high fixed costs and low variable costs.

Railroads come in three general types:

![]() Class I: At least 350 miles in track and/or revenue at least $272 million (in 2002 dollars). Class I carriers comprise only 1% of the number of U.S. freight railroads, but they account for 70% of the industry’s mileage operated, 89% of its employees, and 92% of its freight revenue. Class I carriers typically operate in many different states and concentrate largely (though not exclusively) on long-haul, high-density intercity traffic lanes. There are seven Class I railroads: BNS, Canadian National, Canadian Pacific, CSX Transportation, Kansas City Southern, Norfolk Southern, and Union Pacific.

Class I: At least 350 miles in track and/or revenue at least $272 million (in 2002 dollars). Class I carriers comprise only 1% of the number of U.S. freight railroads, but they account for 70% of the industry’s mileage operated, 89% of its employees, and 92% of its freight revenue. Class I carriers typically operate in many different states and concentrate largely (though not exclusively) on long-haul, high-density intercity traffic lanes. There are seven Class I railroads: BNS, Canadian National, Canadian Pacific, CSX Transportation, Kansas City Southern, Norfolk Southern, and Union Pacific.

![]() Regional and local line haul: Regional railroads are line-haul railroads with at least 350 route miles and/or revenue of between $40 million and the Class I threshold. There were 31 regional railroads in 2002. Regional railroads typically operate 400 to 650 miles of road serving a region located in two to four states.

Regional and local line haul: Regional railroads are line-haul railroads with at least 350 route miles and/or revenue of between $40 million and the Class I threshold. There were 31 regional railroads in 2002. Regional railroads typically operate 400 to 650 miles of road serving a region located in two to four states.

Local line haul carriers operate less than 350 miles and earn less than $40 million per year. In 2002, there were 309 local line haul carriers. They generally perform point-to-point service over short distances. Most operate less than 50 miles of road (more than 20% operate 15 or fewer miles) and serve a single state.

![]() Switching and terminal (S&T) carriers: Railroads that primarily provide switching/terminal services, regardless of revenue. They perform pickup and delivery services within a certain area. In 2002, there were 205 S&T carriers. The largest S&T carriers handle hundreds of thousands of carloads per year and earn tens of millions of dollars in revenue (Association of American Railroads, 2004).

Switching and terminal (S&T) carriers: Railroads that primarily provide switching/terminal services, regardless of revenue. They perform pickup and delivery services within a certain area. In 2002, there were 205 S&T carriers. The largest S&T carriers handle hundreds of thousands of carloads per year and earn tens of millions of dollars in revenue (Association of American Railroads, 2004).

Motor Carriers

Motor carrier is the most widely used mode of transportation in the domestic supply chain; most consumer products are shipped via this method from manufacturers, wholesalers, and distributors to retailers. In fact, there are more than half a million private, for hire, and other U.S. interstate motor carriers.

The economic structure of the motor carrier industry contributes to the vast number of carriers in the industry because it has low fixed and high variable costs.

Motor carriers pay for highway, tunnel, and bridge access through taxes or tolls and provide their own terminals and are fairly fast and flexible because they can offer door-to-door service and are used for small-volume goods to many delivery locations.

Within this mode, there are full-truckload, less-than-truckload (LTL; national and regional), and small-package carriers. Examples of for-hire carriers include Schneider and Werner (TL), Con-way Freight and Old Dominion Freight Line (LTL), and UPS (small package).

Full-truckload carriers have the lowest overhead because they gain economies by filling out one load or trailer with one customer’s freight and go point to point. In contrast, LTL and small-package carriers must have a network of terminals called break bulks for sorting and mixing as each vehicle may have dozens of customer’s small shipments going to a variety of places. This infrastructure is reflected in their rates, as discussed later in the chapter.

Air Carriers

Air cargo carriers are the fastest, most expensive mode of transportation and are an especially important part of many international logistics networks. They use government-provided terminals and air traffic control systems, so they have relatively low fixed costs but operate with high variable costs for fuel and operating costs and tend to haul high-value, lower-volume, and time-sensitive cargo at premium rates.

Some cargo airlines are divisions or subsidiaries of larger passenger airlines; others, such as UPS, FedEx, and DHL, operate for cargo only.

Water Carriers

As noted earlier, water transport is one of the oldest forms of transport. It is divided between domestic and (deepwater) international transport.

Nature provides ways in most cases; however, canals and ports are government controlled. The carrier pays for use of terminals and owns the ships, so there are moderate fixed costs but low operating costs.

This mode is fairly slow and not very flexible and is used to haul low-value bulk cargo over long distances. However, with the advent of containerization in the 1970s, it has become a major facilitator of international trade, carrying 81% international freight movement.

Intermodal Carriers

Intermodal refers to freight being transported in an intermodal container or vehicle. The most widely used intermodal systems are the trailer on a flatcar (TOFC) and container on a rail flatcar (COFC).

This takes advantage of the economies of each mode of transportation (rail, ship, and truck), with no handling of the freight itself when changing modes. As a result, this improves accessibility, reduces cargo handling, and improves security. It also reduces damage and loss and increases the speed with which freight is transported.

It has also helped to facilitate the growth of global trade when used in conjunction with water transport on container ships with standardized containers that are compatible with multiple modes of transport.

Pipeline

Pipelines are a unique mode of transportation used for high-volume gases or liquids moving from point to point. The equipment is fixed in place, and the product moves through it in high volume. There are 174 operators of hazardous liquid pipelines that primarily carry crude oil and petroleum products, the most well known of which is the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS).

Crude oil pipelines are the basis for our liquid energy supply. The crude oil is collected by pipelines from inland production areas like Texas, Louisiana, Alaska, and western Canada. Pipelines also move crude oil produced far offshore in coastal waters as well as from Mexico, Africa and the Middle East, and South America delivered by marine tankers, often moving for the final leg of that trip from a U.S. port to a refinery by pipeline.

In addition, two-thirds of the lower 48 states are almost totally dependent on the interstate pipeline system for their supplies of natural gas.

Global Intermediaries

There also exists as many global intermediaries as there are a variety of services required for international trade. Some of them are as follows:

![]() Freight brokers: Similar to any other type of broker, the main function is to bring together a buyer and a seller. The buyer in this case is the shipper of the goods, and the seller is the trucking company. The broker negotiates the terms of the deal and handles much of the paperwork.

Freight brokers: Similar to any other type of broker, the main function is to bring together a buyer and a seller. The buyer in this case is the shipper of the goods, and the seller is the trucking company. The broker negotiates the terms of the deal and handles much of the paperwork.

![]() Freight forwarders: Heavily utilized in global trade, for both surface and air, to comply with export documentation and shipping requirements, many exporters utilize a freight forwarder to act as their shipping agent. The forwarder advises and assists clients on how to move goods most efficiently from one destination to another. A forwarder has extensive knowledge of documentation requirements, regulations, transportation costs, and banking practices, thus assisting in the exporting process for many companies.

Freight forwarders: Heavily utilized in global trade, for both surface and air, to comply with export documentation and shipping requirements, many exporters utilize a freight forwarder to act as their shipping agent. The forwarder advises and assists clients on how to move goods most efficiently from one destination to another. A forwarder has extensive knowledge of documentation requirements, regulations, transportation costs, and banking practices, thus assisting in the exporting process for many companies.

They may also provide essential freight services such as assembling and consolidation of smaller shipments plus taking larger bulk shipments and breaking them into smaller shipments.

![]() Customs brokers: Perform transactions at ports on for other parties. Typically, an importer hires a customs broker to guide their goods into a country. Similar to the forwarder, the broker will recommend efficient means for clearing goods through customs entry and can also estimate the landed costs for shipments entering the country. U.S. exporters typically do not book shipments directly with a foreign customs broker, because freight forwarders often partner with customs brokers overseas who will clear goods that the forwarder ships to the overseas port. However, foreign customs brokers contract the services of the domestic freight forwarder when the goods are headed in the opposite direction.

Customs brokers: Perform transactions at ports on for other parties. Typically, an importer hires a customs broker to guide their goods into a country. Similar to the forwarder, the broker will recommend efficient means for clearing goods through customs entry and can also estimate the landed costs for shipments entering the country. U.S. exporters typically do not book shipments directly with a foreign customs broker, because freight forwarders often partner with customs brokers overseas who will clear goods that the forwarder ships to the overseas port. However, foreign customs brokers contract the services of the domestic freight forwarder when the goods are headed in the opposite direction.

The types of transactions negotiated for an importer may include the entry of goods into a customs territory, payment of taxes and duties, and duty drawback or refunds of any kind.

![]() Non-vessel-operating common carriers (NVOCCs): NVOCCs are also freight forwarders, except that they 1) may own and operate and sometimes lease the containers they ship, 2) be required to publish a public tariff (that is, rates), 3) may have to take on the status of a virtual carrier and take on liabilities of a carrier, and 4) whereas freight forwarders can be agents for an NVOCC, the reverse is not true, giving NVOCCs more flexibility.

Non-vessel-operating common carriers (NVOCCs): NVOCCs are also freight forwarders, except that they 1) may own and operate and sometimes lease the containers they ship, 2) be required to publish a public tariff (that is, rates), 3) may have to take on the status of a virtual carrier and take on liabilities of a carrier, and 4) whereas freight forwarders can be agents for an NVOCC, the reverse is not true, giving NVOCCs more flexibility.

Legal Types of Carriage

There are two legal types of carriers, for hire and private, as described here.

For Hire

For-hire carriers offer service to the general public and are subject to government regulations in regard to rates, routes, and markets served.

They come in two major forms:

![]() Common carriers: Licensed to carry only certain goods available to public to designated points or areas served and offer scheduled service. Common carriers must file both liability insurance and cargo insurance. Public airlines, railroads, bus lines, taxicab companies, cruise ships, motor carriers, and other freight companies generally operate as common carriers (as do communications service providers and public utilities).

Common carriers: Licensed to carry only certain goods available to public to designated points or areas served and offer scheduled service. Common carriers must file both liability insurance and cargo insurance. Public airlines, railroads, bus lines, taxicab companies, cruise ships, motor carriers, and other freight companies generally operate as common carriers (as do communications service providers and public utilities).

![]() Contract carriers: For-hire interstate operators that offer transportation services to certain shippers under contracts. Contract carriers must file only liability insurance.

Contract carriers: For-hire interstate operators that offer transportation services to certain shippers under contracts. Contract carriers must file only liability insurance.

There are also independent carriers, referring to an individual owner-operator or trucker who can make agreements with private carriers, common carriers, contract carriers, or others as they want.

Private

Carriers are considered private when a company transports only their own goods. Their primary business is not transportation, and the vehicles are not for hire. Private carriage usually refers to trucking, but is also found in rail and water transportation.

Very high volume or specific needs are needed to justify the expense. Many retail organizations, as well as some manufacturers, distributors, and wholesalers, operate their own fleets. We’ve all seen Walmart and Toys R Us trucks (with Jeffrey Giraffe) printed on the side of the trailer on a highway at one time or another. These are examples of private carriage.

In many cases, private vehicles such as those mentioned here can also be used to backhaul freight from suppliers after delivering product from distribution facilities to retail locations. This can avoid the need for the vehicle to make the return trip empty and to reduce their fleets’ overall operating costs.

Transportation Economics

In this section, we will deal with the application of demand and cost principles to transportation.

Transportation Cost Factors and Elements

There are a variety of factors that impact transportation costs, which we will now cover.

Cost Factors

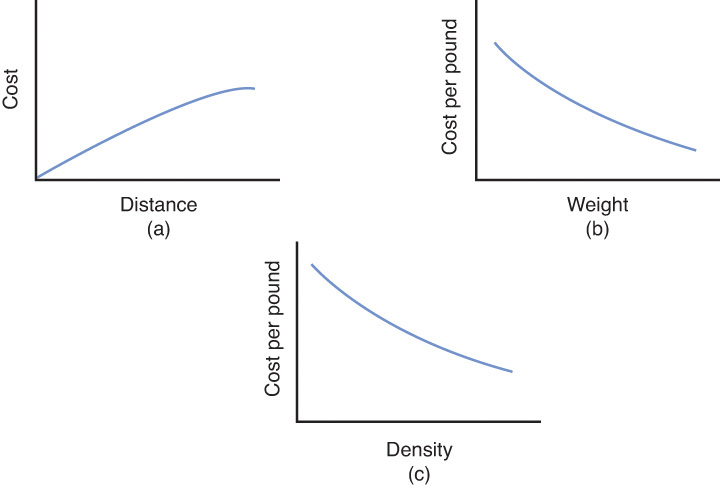

The primary factors influencing transportation costs pricing are distance, weight, and density (see Figure 7.2a, b, c).

![]() Distance: As distance traveled increases, variable expenses such as labor, fuel, and maintenance increase.

Distance: As distance traveled increases, variable expenses such as labor, fuel, and maintenance increase.

![]() Weight: The transport cost per unit decreases as the load weight increases. This is as a result of economies of scale as a result of spreading the fixed costs over more weight. That is why it is always best to combine small loads into larger ones where possible, up to the capacity of the vehicle carrying the load.

Weight: The transport cost per unit decreases as the load weight increases. This is as a result of economies of scale as a result of spreading the fixed costs over more weight. That is why it is always best to combine small loads into larger ones where possible, up to the capacity of the vehicle carrying the load.

![]() Density: This is the combination of weight and cubic volume. Vehicles have both weight and cubic capacity and tend to cube out before weighting out. So, shipping higher-density products enables the cost to be spread over more weight versus a lighter load such as paper cups, where you are shipping a lot of air for your money. As a result, higher-density products are charged less per hundredweight or CWT (that is, per hundred pounds; one of the common forms of transportation pricing, which is discussed shortly).

Density: This is the combination of weight and cubic volume. Vehicles have both weight and cubic capacity and tend to cube out before weighting out. So, shipping higher-density products enables the cost to be spread over more weight versus a lighter load such as paper cups, where you are shipping a lot of air for your money. As a result, higher-density products are charged less per hundredweight or CWT (that is, per hundred pounds; one of the common forms of transportation pricing, which is discussed shortly).

![]() Stowability: Similar to density and is also a factor. It refers more to the ease of storage, such as when shipping items are easily stacked or nested.

Stowability: Similar to density and is also a factor. It refers more to the ease of storage, such as when shipping items are easily stacked or nested.

![]() Other factors: Can includes factors such as the amount of handling necessary (smaller volumes typically require more handling), type of handling (full pallets can be handled with more automated equipment versus individual cases, which are handled manually in most cases), liability (can be a function of the value or nature of the product), perishability, and market factors such as market (origin and destination) volume and balance, which refers to amount of freight flowing both ways. Finally, an empty return or backhaul can be costly to the carrier and thus may affect rates into an area that has very little freight coming out. (For example, because there is very little manufacturing in Florida, rates into the state may be high because carriers have a hard time finding freight for the return trip.)

Other factors: Can includes factors such as the amount of handling necessary (smaller volumes typically require more handling), type of handling (full pallets can be handled with more automated equipment versus individual cases, which are handled manually in most cases), liability (can be a function of the value or nature of the product), perishability, and market factors such as market (origin and destination) volume and balance, which refers to amount of freight flowing both ways. Finally, an empty return or backhaul can be costly to the carrier and thus may affect rates into an area that has very little freight coming out. (For example, because there is very little manufacturing in Florida, rates into the state may be high because carriers have a hard time finding freight for the return trip.)

Shipping Patterns

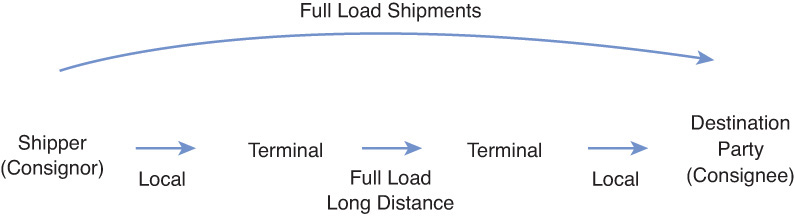

There are a variety of shipping patterns, as shown in Figure 7.3. A shipment may go direct from the origin point to destination or make one or more stops in between. This will depend on the primary cost factors mentioned above (for example, TL versus LTL).

![]() Line haul: Carriers have basic costs to move product from point to point that include fuel, labor, and depreciation. The costs are pretty much the same per mile whether the container is full or empty, so the line haul cost is total of these costs divided by the distance traveled.

Line haul: Carriers have basic costs to move product from point to point that include fuel, labor, and depreciation. The costs are pretty much the same per mile whether the container is full or empty, so the line haul cost is total of these costs divided by the distance traveled.

So, for example, if the line haul cost to transport material from point A to point B is $5 per mile and the route is 500 miles, the total line haul cost is $2,500. The actual cost (in $/CWT) for a shipment weighing 12,000 pounds is $20.83/CWT (that is, $2,500 / 120), and the cost for a shipment weighing 45,000 pounds is $5.56/CWT.

As a result, the total line haul cost will vary with the cost per mile to operate the vehicle and the distance the material is moved. The line haul cost per hundredweight varies based on the cost per mile, distance, and weight, as you learned in the earlier example.

Other line haul services may be required, as well, including the following:

![]() Reconsignment: This involves changing the consignee while the shipment is in transit and is used commonly in industries where goods are shipped before they are sold.

Reconsignment: This involves changing the consignee while the shipment is in transit and is used commonly in industries where goods are shipped before they are sold.

![]() Diversion: The changing of the destination of a shipment while in transit, which is often used in conjunction with reconsignment.

Diversion: The changing of the destination of a shipment while in transit, which is often used in conjunction with reconsignment.

![]() Pooling: This allows a shipper to use a less-costly container or truckload rate by consolidating smaller shipments going to one destination and one consignee into one pool car or truck.

Pooling: This allows a shipper to use a less-costly container or truckload rate by consolidating smaller shipments going to one destination and one consignee into one pool car or truck.

![]() Stopping in transit: This allows the shipper to use a full container or truckload rate and drop off portions of the load at various intermediate destinations. The shipper is invoiced for a stop-off charge for each stop, which is usually a lot less than shipping the load at less than car or truck load rates.

Stopping in transit: This allows the shipper to use a full container or truckload rate and drop off portions of the load at various intermediate destinations. The shipper is invoiced for a stop-off charge for each stop, which is usually a lot less than shipping the load at less than car or truck load rates.

![]() Transit privilege: This allows for the shipper to unload a car or trailer, process the shipment, and then reload and ship the processed product to its final destination using a through rate (that is, a single transportation rate on an interline haul made up of two or more separately established rates).

Transit privilege: This allows for the shipper to unload a car or trailer, process the shipment, and then reload and ship the processed product to its final destination using a through rate (that is, a single transportation rate on an interline haul made up of two or more separately established rates).

![]() Pickup and delivery: These costs depend on the time spent picking up and dropping off cargo and not distance. There is a charge for each pickup, so it is useful to consolidate multiple shipments to avoid multiple separate trips.

Pickup and delivery: These costs depend on the time spent picking up and dropping off cargo and not distance. There is a charge for each pickup, so it is useful to consolidate multiple shipments to avoid multiple separate trips.

The loading and unloading of freight at pickup and delivery is generally the responsibility of the carrier in the case of LTL or LCL (and small-package) shipments, whereas the shipper is usually responsible for TL and CL loading and unloading.

The carrier will specify the amount of time the shipper and receiver have for loading and unloading. In the case of rail free time, this is 24 to 48 hours; after free time, rail carriers charge what is called a demurrage fee; motor charge what is called a detention fee. Motor carrier loading and unloading times vary, but can be as little as a half hour.

![]() Terminal handling: These costs depend on how many times the shipment must be handled. In the case of full truckloads (TL), there is no terminal handling because they go directly to the customer. However, LTL shipments must be sent to a terminal, sorted, and consolidated, so charges are incurred. As a result, it is wise to consolidate shipments into fewer parcels where possible.

Terminal handling: These costs depend on how many times the shipment must be handled. In the case of full truckloads (TL), there is no terminal handling because they go directly to the customer. However, LTL shipments must be sent to a terminal, sorted, and consolidated, so charges are incurred. As a result, it is wise to consolidate shipments into fewer parcels where possible.

There are other terminal services besides handling, including the following:

![]() Consolidation: Many small shipments are consolidated into a one larger shipment going to a customer, qualifying the shipper for a lower rate.

Consolidation: Many small shipments are consolidated into a one larger shipment going to a customer, qualifying the shipper for a lower rate.

![]() Dispersion: This is the opposite of consolidation, with one large shipment being distributed to multiple customers at the destination terminal.

Dispersion: This is the opposite of consolidation, with one large shipment being distributed to multiple customers at the destination terminal.

![]() Shipment services: The carrier provides freight handling for consolidation or dispersion.

Shipment services: The carrier provides freight handling for consolidation or dispersion.

![]() Vehicle service: Carriers need to maintain a diverse and adequate fleet of transit vehicles for shipper’s use.

Vehicle service: Carriers need to maintain a diverse and adequate fleet of transit vehicles for shipper’s use.

![]() Interchange: Carriers must provide the ability to interconnect with other carriers of the same or different modes so that through rates may be used by the shipper.

Interchange: Carriers must provide the ability to interconnect with other carriers of the same or different modes so that through rates may be used by the shipper.

![]() Weighing: The carrier (or shipper) provides the weight of shipment.

Weighing: The carrier (or shipper) provides the weight of shipment.

![]() Tracing: Carriers can communicate to shipper where the shipment is and when it might be delivered. In most cases, this information can be supplied via the Internet.

Tracing: Carriers can communicate to shipper where the shipment is and when it might be delivered. In most cases, this information can be supplied via the Internet.

![]() Expediting: In some cases, it is necessary to move a shipment faster than normal, and as a result, this may require a premium over-regular handling.

Expediting: In some cases, it is necessary to move a shipment faster than normal, and as a result, this may require a premium over-regular handling.

![]() Billing and collecting: This includes the costs of paperwork and invoicing the shipper. Carriers also provide clerical services for bills of lading (documents issued by a carrier for a shipment of merchandise giving title of that shipment to a specified party), freight bills, and routing of the shipment.

Billing and collecting: This includes the costs of paperwork and invoicing the shipper. Carriers also provide clerical services for bills of lading (documents issued by a carrier for a shipment of merchandise giving title of that shipment to a specified party), freight bills, and routing of the shipment.

Rates Charged

Now that we you understand the general economics of transportation cost and it its major elements, let’s turn our focus to pricing.

Effects of Deregulation on Pricing

Since deregulation, transportation rates or prices are negotiated like other commodities. Some changes as a result of deregulation by mode are as follows:

![]() Motor and water carriers: Rate and tariff-filing regulations were eliminated except for household and noncontiguous trade for domestic water transportation (that is, shipments that originate or terminate in Alaska, Hawaii, or a U.S. territory or possession). The common carriage concept was for the most part eliminated, as all carriers may contract with shippers. Antitrust immunity for collective ratemaking was eliminated.

Motor and water carriers: Rate and tariff-filing regulations were eliminated except for household and noncontiguous trade for domestic water transportation (that is, shipments that originate or terminate in Alaska, Hawaii, or a U.S. territory or possession). The common carriage concept was for the most part eliminated, as all carriers may contract with shippers. Antitrust immunity for collective ratemaking was eliminated.

![]() Air carriers: As mentioned earlier, economic regulation of air carriers was eliminated in 1977. However, safety regulation remains in force.

Air carriers: As mentioned earlier, economic regulation of air carriers was eliminated in 1977. However, safety regulation remains in force.

![]() Rail carriers: This is still the most regulated of the transportation modes. There has been, however, complete deregulation over certain types of traffic: piggyback and fresh fruits.

Rail carriers: This is still the most regulated of the transportation modes. There has been, however, complete deregulation over certain types of traffic: piggyback and fresh fruits.

![]() Freight forwarders and brokers: Both are required to register with the Surface Transportation Board (STB). Brokers must also post a $75,000 bond to ensure payment to the carriers. No economic rate or service controls these entities. A freight forwarder is considered a carrier and is liable for freight damages.

Freight forwarders and brokers: Both are required to register with the Surface Transportation Board (STB). Brokers must also post a $75,000 bond to ensure payment to the carriers. No economic rate or service controls these entities. A freight forwarder is considered a carrier and is liable for freight damages.

Pricing Specifics

Full container or truck load rates may be expressed in a flat dollar or mileage rate, and less than containers or truckloads may be a discount off of the class rate from the tariff.

In general, prices (known as rates) are expressed in either dollars (whole or per mile) or cents per hundredweight (CWT) and are contained in tariffs, which can be in hard copy or electronic form.

Freight Classifications

The classification of an item must first be determined. The classification is based on the cost elements of an item mentioned earlier: density, stowability, ease of handling, and liability. The class given to an item is known as its rating.

Truck and rail each have their own set of classifications. For motor carriers, it is the National Motor Freight Classification (NMFC), and for rail, it is the Uniform Freight Classification (UFC).

A class of 100 is considered average. A class can range from 35 to 500. (In general, the higher the rating, the higher the transportation cost.)

Rate Determination

After the class is identified, the rate must be determined and is based on the origin and destination. There is usually a minimum charge and various rates at weight breaks as the shipments increase in size. There may also be rate surcharges or accessorial charges for extra services provided by the carrier.

There are also other types of rates, such as the following:

![]() Cube or density rates: Freight rate computed on the basis of a cargo’s volume, instead of its weight.

Cube or density rates: Freight rate computed on the basis of a cargo’s volume, instead of its weight.

![]() Exception rates: A deviation from the class rate; changes (exceptions) made to the classification.

Exception rates: A deviation from the class rate; changes (exceptions) made to the classification.

![]() Commodity rates: The carrier will offer an all-commodity rate for this specific route despite the class of the commodity carried. The class of the commodity does not matter to the carrier.

Commodity rates: The carrier will offer an all-commodity rate for this specific route despite the class of the commodity carried. The class of the commodity does not matter to the carrier.

![]() Freight-all-kinds (FAK) rates: These are rates for a carrier’s tariff classification for various kinds of goods that are pooled and shipped together at one freight rate. Consolidated shipments are generally classified as FAK.

Freight-all-kinds (FAK) rates: These are rates for a carrier’s tariff classification for various kinds of goods that are pooled and shipped together at one freight rate. Consolidated shipments are generally classified as FAK.

Documents

A variety of documents are used in transportation both domestically and internationally. This section covers the main ones in this section.

Domestic Transportation Documents

Before discussing the major domestic documents, it is first useful to understand terms of sale.

Terms of Sale

Transportation costs are the second- or third-highest expense that a manufacturing company has beyond the cost of labor and raw materials, so it makes sense to know how they are allocated. Even if your vendor pays the freight charges, you need to know the amount they paid, because at some point when you have enough volume, you may want to take control of your inbound freight and negotiate rates with your own carriers to less than you are paying now. You should always identify freight costs separate from cost of goods.

Negotiating the most appropriate terms of sale will allow you to add value to your purchase.

The terms determine which party is to pay the freight bill, which party has title to the goods, and which party controls the movement of the goods.

The two major terms are as follows:

![]() F.O.B. origin: The buyer pays for the freight, takes title to the goods once loaded, and controls movement of the goods.

F.O.B. origin: The buyer pays for the freight, takes title to the goods once loaded, and controls movement of the goods.

![]() F.O.B. destination: The seller pays for the freight, has title to the goods until they are delivered, and controls movement of the goods.

F.O.B. destination: The seller pays for the freight, has title to the goods until they are delivered, and controls movement of the goods.

There are variations to these terms, as follows:

![]() F.O.B. origin, freight collect: The buyer pays freight charges, owns goods in transit, and files claims, if any.

F.O.B. origin, freight collect: The buyer pays freight charges, owns goods in transit, and files claims, if any.

![]() F.O.B. origin, freight prepaid: The seller pays freight charges, and the buyer owns goods in transit and files claims, if any.

F.O.B. origin, freight prepaid: The seller pays freight charges, and the buyer owns goods in transit and files claims, if any.

![]() F.O.B. origin, freight prepaid and charged back: The seller pays freight charges, owns goods in transit, and the buyer files claims, if any.

F.O.B. origin, freight prepaid and charged back: The seller pays freight charges, owns goods in transit, and the buyer files claims, if any.

![]() F.O.B. destination, freight collect: The buyer pays freight charges, and the seller owns goods in transit and files claims, if any.

F.O.B. destination, freight collect: The buyer pays freight charges, and the seller owns goods in transit and files claims, if any.

![]() F.O.B. destination, freight prepaid: The seller pays freight charges, owns goods in transit, and files claims, if any.

F.O.B. destination, freight prepaid: The seller pays freight charges, owns goods in transit, and files claims, if any.

![]() F.O.B. destination, freight collect and allowed: The buyer pays freight charges, and the seller owns goods in transit and files claims, if any.

F.O.B. destination, freight collect and allowed: The buyer pays freight charges, and the seller owns goods in transit and files claims, if any.

Bill of Lading

A bill of lading (B/L) is a contract between the carrier and the shipper issued by a carrier, which details a shipment of merchandise and gives title of that shipment to a specified party (that is, a receipt) with specified timing.

A B/L includes title to the goods and name and address of the consignor and consignee and summarizes the goods in transit and their class rates. Electronic bills are now used often where the carrier and shipper have an established strategic partnership.

There are two main types of B/Ls:

![]() (Uniform) straight bill of lading: These are nonnegotiable and contain terms of the sale, including the time and place of title transfer.

(Uniform) straight bill of lading: These are nonnegotiable and contain terms of the sale, including the time and place of title transfer.

![]() Order (notified) bill of lading: These are negotiable, and the consignor retains the original until the bill is paid. They can be used as a credit instrument because there is no delivery unless the original bill of lading is surrendered to the carrier.

Order (notified) bill of lading: These are negotiable, and the consignor retains the original until the bill is paid. They can be used as a credit instrument because there is no delivery unless the original bill of lading is surrendered to the carrier.

There are also export bills of lading (covered in the section “International Transportation Documents”) and government bills of lading. Government B/Ls are used when the product is owned by the U.S. government.

In cases where there are individual stops or consignees when multiple shipments are placed on a single vehicle, what is known as a shipment manifest is used. Each shipment still requires a B/L, and the manifest lists the stop, B/L, weight, and case count for each shipment. The goal of a manifest is to provide one document that describes the complete contents of the load.

The B/L also documents responsibilities for all possible causes of loss or damage and includes terms such as the following:

![]() Common carrier liable for all losses, damage, or delays in shipment.

Common carrier liable for all losses, damage, or delays in shipment.

![]() Exceptions include acts of God, public enemy, shipper, public authority, and inherent nature of the goods.

Exceptions include acts of God, public enemy, shipper, public authority, and inherent nature of the goods.

![]() Reasonable dispatch.

Reasonable dispatch.

![]() Shipper liable for mending, cooperage, bailing, or reconditioning of goods or packages and gathering of loose contents for packages.

Shipper liable for mending, cooperage, bailing, or reconditioning of goods or packages and gathering of loose contents for packages.

![]() Freight not accepted stored at owner’s cost.

Freight not accepted stored at owner’s cost.

Freight Bills

Freight bills are the carrier’s invoice for charges for a given shipment. The credit terms are specified by the carrier and can vary extensively. In some cases, credit may be denied if the charges are worth more than the freight.

Bills may also be either prepaid or collect per the previous discussion on freight terms.

Because there tends to be large changes to fuel costs, low visibility of the future freight costs, and a relatively high complexity of freight quotes, freight invoices are susceptible to human and process errors and require auditing to ensure that the organization does not overpay for services it did not incur.

These audits can be performed internally or externally, both prepayment and, in some cases, postpayment.

When I worked in General Electric Corporate Sourcing, I helped to establish the GE Corporate Freight Payment Center in Fort Myers, Florida. The two major goals of the service was to both consolidate information for their 100 or so business units to leverage the over $1 billion spent company-wide on transportation services and to perform a pre-audit on freight bills in a more standardized, automated fashion (because freight bill errors, including overcharges and duplicate bills and payments, can range as high as 5% domestically and even as high as 10% internationally).

Freight Claims

A freight claim is a document filed with the carrier to recover monetary losses due to losses, damage, delay, or overcharges by the carrier. In most cases, claims are filed within 9 months, the claimant is notified by receipt within 30 days, and settlement or refusal usually occurs within 120 days.

The claimants are expected to take some reasonable measures to minimize the loss, such as requiring the carrier to pay for the difference between the original value and the damaged or salvage value.

International Transportation Documents

By its very nature, documentation for international transportation is much more complex than required for domestic transportation. The types of documents vary widely by country and fall into two major categories of sales and transportation.

Sales Documents

A sales contract is usually the initial document used international trade. A letter of credit, a document issued by a financial institution ensuring payment to a seller of goods or services, may also accompany shipment.

For export, one may need an export license, which is the express authorization by a country’s government to export a specific product before it is shipped. Governments may require an export license to exert some control over foreign trade for political or military reasons, control the export of natural resources, or control the export of national treasures or antiques.

Also for export, a shipper’s export declaration is required by U.S. Customs, which is designed to keep track of the type of goods exported from the United States, as well as their destination and their value.

There may also be export taxes and quotas in effect.

For import, countries require certain documents to ensure that no shoddy quality goods are imported; and to help determine the appropriate tariff classification, the correct value of imported goods, the correct country of origin for tariff purposes; or to protect importers from fraudulent exporters or limit (or eliminate) imports of products that the government finds inappropriate for whatever reason.

Import documents include the following:

![]() Certificate of origin: A document provided by the exporter’s chamber of commerce that attests that the goods originated from the country in which the exporter is located. It is used by the importing country to determine tariff of goods.

Certificate of origin: A document provided by the exporter’s chamber of commerce that attests that the goods originated from the country in which the exporter is located. It is used by the importing country to determine tariff of goods.

![]() Certificate of manufacture: A document provided by the exporter’s chamber of commerce that attests that the goods were manufactured in the country in which the exporter is located.

Certificate of manufacture: A document provided by the exporter’s chamber of commerce that attests that the goods were manufactured in the country in which the exporter is located.

![]() Certificate of inspection: A document provided by an independent inspection company that attests that the goods conform to the description contained in the invoice provided by the exporter and that the value of the goods is reflected accurately on the invoice. It is always obtained by the exporter in the exporting country, before the international voyage takes place, and the certificate of inspection is the result of a pre-shipment inspection (PSI).

Certificate of inspection: A document provided by an independent inspection company that attests that the goods conform to the description contained in the invoice provided by the exporter and that the value of the goods is reflected accurately on the invoice. It is always obtained by the exporter in the exporting country, before the international voyage takes place, and the certificate of inspection is the result of a pre-shipment inspection (PSI).

![]() Certificate of free sale: This shows that the goods sold by the exporter can legally be sold in the country of export; this certificate is designed to prevent the export of products that would be considered defective in the country of export.

Certificate of free sale: This shows that the goods sold by the exporter can legally be sold in the country of export; this certificate is designed to prevent the export of products that would be considered defective in the country of export.

![]() Import license: A document issued by the importing country that is designed to prevent import of nonessential or overly luxurious products in developing countries short of foreign currency supply.

Import license: A document issued by the importing country that is designed to prevent import of nonessential or overly luxurious products in developing countries short of foreign currency supply.

![]() Certificate of insurance: Some international terms of sale, or Incoterms (International Commerce Terms), require that the exporter provide insurance, and a certificate of insurance offers this proof of coverage.

Certificate of insurance: Some international terms of sale, or Incoterms (International Commerce Terms), require that the exporter provide insurance, and a certificate of insurance offers this proof of coverage.

![]() Carnet: International customs documents that simplify customs procedures for the temporary importation of various types of goods. They ease the temporary importation of commercial samples, professional equipment, and goods for exhibitions and fairs by avoiding extensive customs procedures and eliminating payment of duties and value-added taxes (minimum 20% in Europe, 27% in China); they replace the purchase of temporary import bonds.

Carnet: International customs documents that simplify customs procedures for the temporary importation of various types of goods. They ease the temporary importation of commercial samples, professional equipment, and goods for exhibitions and fairs by avoiding extensive customs procedures and eliminating payment of duties and value-added taxes (minimum 20% in Europe, 27% in China); they replace the purchase of temporary import bonds.

Terms of Sale

International Commercial Terms, also known as Incoterms, are a set of rules that define the responsibilities of sellers and buyers for the delivery of goods under sales contracts for domestic and international trade. They are published by the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) and are widely used in international commercial transactions. They provide a common set of rules to apportion transportation costs and clarify responsibilities of sellers and buyers for the delivery of goods under sales contracts. The goal is to simplify the drafting of contracts and help avoid misunderstandings by clearly describing the obligations of buyers and sellers.

The terms may include export packing costs, inland transportation, export clearance, vehicle loading, transportation costs, insurance, and duties.

The two main categories of Incoterms® 2010 are now organized by modes of transport:

![]() Group 1: Incoterms® that apply to any mode of transport.

Group 1: Incoterms® that apply to any mode of transport.

![]() EXW Ex Works

EXW Ex Works

![]() FCA Free Carrier

FCA Free Carrier

![]() CPT Carriage Paid To

CPT Carriage Paid To

![]() CIP Carriage and Insurance Paid To

CIP Carriage and Insurance Paid To

![]() DAT Delivered at Terminal

DAT Delivered at Terminal

![]() DAP Delivered at Place

DAP Delivered at Place

![]() DDP Delivered Duty Paid

DDP Delivered Duty Paid

![]() Group 2: Incoterms® that apply to sea and inland waterway transport only.

Group 2: Incoterms® that apply to sea and inland waterway transport only.

![]() FAS Free Alongside Ship

FAS Free Alongside Ship

![]() FOB Free on Board

FOB Free on Board

![]() CFR Cost and Freight

CFR Cost and Freight

![]() CIF Cost, Insurance, and Freight

CIF Cost, Insurance, and Freight

International Transportation Documents

Transport documents are a crucial part of international trade transactions. The documents are issued by the shipping line, airline, international trucking company, railroad, freight forwarder, or logistics companies.

To the shipping company and freight forwarder, transport documents provide an accounting record of the transaction, instructions on where and how to ship the goods, and a statement giving instructions for handling the shipment.

International Bill of Lading

B/Ls in international trade help guarantee that exporters receive payment and that importers receive merchandise. The export B/L can govern foreign,, intercountry, and domestic movements of the goods.

An international B/L can have a number of additional attributes, such as on-board, received-for-shipment, clean, and foul. An on-board B/L denotes that merchandise has been physically loaded onto a shipping vessel, such as a freighter or cargo plane. A received-for-shipment B/L denotes that merchandise has been received, but is not guaranteed to have already been loaded onto a shipping vessel. Such bills can be converted upon being loaded.

Some of the specific types of B/Ls related to international transportation include the following. (Straight and intermodal for domestic have already been discussed.)

![]() Ocean bill of lading: Sets terms and lists origin and destination ports, quantities and weight, rates, and special handling needs for the ocean movement. The ocean carrier is held liable for losses due to negligence only, with other losses being the responsibility of the shipper. A commercial invoice determines the value of the products in the case of losses due to negligence.

Ocean bill of lading: Sets terms and lists origin and destination ports, quantities and weight, rates, and special handling needs for the ocean movement. The ocean carrier is held liable for losses due to negligence only, with other losses being the responsibility of the shipper. A commercial invoice determines the value of the products in the case of losses due to negligence.

![]() Air waybill: A B/L used in the transportation of goods by air, domestically or internationally.

Air waybill: A B/L used in the transportation of goods by air, domestically or internationally.

B/Ls can also be for receipt or title to goods in the form of a

![]() Negotiable or to order B/L: A negotiable B/L allows the owner of the goods to sell them while they are in international transit. The transfer of ownership to the new owner is done with the B/L, because it is a certificate of title to the goods. Only ocean B/Ls can be negotiable.

Negotiable or to order B/L: A negotiable B/L allows the owner of the goods to sell them while they are in international transit. The transfer of ownership to the new owner is done with the B/L, because it is a certificate of title to the goods. Only ocean B/Ls can be negotiable.

![]() Clean B/L: This type of B/L is used as a receipt for goods and is issued by carrier when goods arrive in port; damages and other exceptions should be noted. (A foul B/L denotes that merchandise has incurred damage prior to being received by the shipping carrier. Letters of credit usually will not allow for foul B/Ls.)

Clean B/L: This type of B/L is used as a receipt for goods and is issued by carrier when goods arrive in port; damages and other exceptions should be noted. (A foul B/L denotes that merchandise has incurred damage prior to being received by the shipping carrier. Letters of credit usually will not allow for foul B/Ls.)

Key Metrics

In addition to budgeting transportation costs by mode and by lane, a variety of performance measurements are used in transportation for current performance versus historical results, internal goals, and carrier commitments. The main categories of key metrics are service quality and efficiency and may include on-time delivery, loss and damage rate, billing accuracy, equipment condition, and customer service.

Technology

Transportation management systems (TMSs) have been around for a long while. Historically, they have been an add-on to an existing enterprise resource planning (ERP) or legacy (that is, homegrown) order-processing or warehouse management system (WMS).

Like most software today, they can be installed as resident software or web based and accessed on demand.

A TMS offers benefits to an organization such as automated auditing and billing, optimized operations, and improved visibility.

They typically include functionality to plan, schedule, and control an organization’s transportation system, with functionality for the following:

![]() Planning and decision making: Helps to define the most efficient transport schemes according to parameters such as the following: transportation cost, lead time, stops, and so on. Also includes inbound and outbound transportation mode and transportation provider selection and vehicle load and route optimization.

Planning and decision making: Helps to define the most efficient transport schemes according to parameters such as the following: transportation cost, lead time, stops, and so on. Also includes inbound and outbound transportation mode and transportation provider selection and vehicle load and route optimization.

![]() Transportation execution: Allows for the execution of a transportation plan such as carrier rate acceptance, carrier dispatching, electronic data interchange (EDI), and so on.

Transportation execution: Allows for the execution of a transportation plan such as carrier rate acceptance, carrier dispatching, electronic data interchange (EDI), and so on.

![]() Transport follow-up: Tracking of physical or administrative transportation operations such as traceability of transport event by receipt, custom clearance, invoicing and booking documents, and sending of transport alerts (delay, accident, and so on).

Transport follow-up: Tracking of physical or administrative transportation operations such as traceability of transport event by receipt, custom clearance, invoicing and booking documents, and sending of transport alerts (delay, accident, and so on).

![]() Measurement: Cost control and key performance indicator (KPI) reporting as it relates to transportation.

Measurement: Cost control and key performance indicator (KPI) reporting as it relates to transportation.

Ultimately, a supply chain system is made up of connecting links and nodes, where the transportation system provides the links, and the facilities provide the nodes. Therefore, the next logical topic to cover is warehouse management and operations.