2. How to Think in Terms of Objects

In Chapter 1, “Introduction to Object-Oriented Concepts,” you learned the fundamental object-oriented (OO) concepts. The rest of the book delves more deeply into these concepts and introduces several others. Many factors go into a good design, whether it is an OO design or not. The fundamental unit of OO design is the class. The desired end result of OO design is a robust and functional object model—in other words, a complete system.

As with most things in life, there is no single right or wrong way to approach a problem. There are usually many ways to tackle the same problem. So when attempting to design an OO solution, don’t get hung up in trying to do a perfect design the first time (there will always be room for improvement). What you really need to do is brainstorm and let your thought process go in different directions. Do not try to conform to any standards or conventions when trying to solve a problem because the whole idea is to be creative.

In fact, at the start of the process, don’t even begin to consider a specific programming language. The first order of business is to identify and solve business problems. Work on the conceptual analysis and design first. Think about specific technologies only when they are fundamental to the business problem. For example, you can’t design a wireless network without wireless technology. However, it is often the case that you will have more than one software solution to consider.

Thus, before you start to design a system, or even a class, think the problem through and have some fun! In this chapter we explore the fine art and science of OO thinking.

Any fundamental change in thinking is not trivial. As a case in point, a lot has been mentioned about the move from structured to OO development. As was mentioned earlier, one side effect of this debate is the misconception that structured and object-oriented development are mutually exclusive. This is not the case. As we know from our discussion on wrappers, structured and object-oriented development coexist. In fact, when you write an OO application, you are using structured constructs everywhere. I have never seen a program, OO or otherwise, that does not use loops, if-statements, and so on. Yet making the switch to OO design does require a different type of investment.

Changing from FORTRAN to COBOL, or even to C, requires you to learn a new language; however, making the move from COBOL to C++, C# .NET, Visual Basic .NET, Objective-C, Swift, or Java requires you to learn a new thought process. This is where the overused phrase OO paradigm rears its ugly head. When moving to an OO language, you must first go through the investment of learning OO concepts and the corresponding thought process. If this paradigm shift does not take place, one of two things will happen: Either the project will not truly be OO in nature (for example, it will use C++ without using OO constructs) or the project will be a complete object-disoriented mess.

Three important things you can do to develop a good sense of the OO thought process are covered in this chapter:

Knowing the difference between the interface and implementation

Thinking more abstractly

Giving the user the minimal interface possible

We have already touched on some of these concepts in Chapter 1, “Introduction to Object-Oriented Concepts,” and we now go into much more detail.

Knowing the Difference Between the Interface and the Implementation

As we saw in Chapter 1, one of the keys to building a strong OO design is to understand the difference between the interface and the implementation. Thus, when designing a class, what the user needs to know and, perhaps of more importance, what the user does not need to know are of vital importance. The data hiding mechanism inherent with encapsulation is the means by which nonessential data is hidden from the user.

Caution

Do not confuse the concept of the interface with terms like graphical user interface (GUI). Although a GUI is, as its name implies, an interface, the term interfaces, as used here, is more general in nature and is not restricted to a graphical interface.

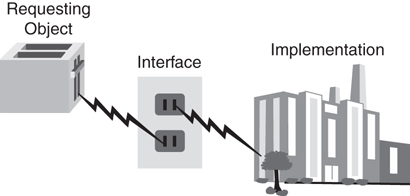

Remember the toaster example in Chapter 1? The toaster, or any appliance for that matter, is plugged into the interface, which is the electrical outlet—see Figure 2.1. All appliances gain access to the required electricity by complying with the correct interface: the electrical outlet. The toaster doesn’t need to know anything about the implementation or how the electricity is produced. For all the toaster cares, a coal plant or a nuclear plant could produce the electricity—the appliance does not care which, as long as the interface works as specified, correctly and safely.

As another example, consider an automobile. The interface between you and the car includes components such as the steering wheel, gas pedal, brake, and ignition switch. For most people, aesthetic issues aside, the main concern when driving a car is that the car starts, accelerates, stops, steers, and so on. The implementation, basically the stuff that you don’t see, is of little concern to the average driver. In fact, most people would not even be able to identify certain components, such as the catalytic converter and gasket. However, any driver would recognize and know how to use the steering wheel because this is a common interface. By installing a standard steering wheel in the car, manufacturers are assured that the people in their target market will be able to use the system.

If, however, a manufacturer decided to install a joystick in place of the steering wheel, most drivers would balk at this, and the automobile might not be a big seller (except possibly gamers). On the other hand, as long as the performance and aesthetics didn’t change, the average driver would not notice whether the manufacturer changed the engine (part of the implementation) of the automobile.

It must be stressed that the interchangeable engines must be identical in every way—as far as the interface goes. Replacing a four-cylinder engine with an eight-cylinder engine would change the rules and likely would not work with other components that interface with the engine, just as changing the current from AC to DC would affect the rules in the power plant example.

The engine is part of the implementation, and the steering wheel is part of the interface. A change in the implementation should have no impact on the driver, whereas a change to the interface might. The driver would notice an aesthetic change to the steering wheel, even if it performs in a similar manner. It must be stressed that a change to the engine that is noticeable by the driver breaks this rule. For example, a change that would result in noticeable loss of power is actually impacting the interface.

What Users See

When we talk about users in this chapter, we primarily mean designers and developers—not necessarily end users. Thus, when we talk about interfaces in this context, we are talking about class interfaces, not GUIs.

Properly constructed classes are designed in two parts—the interface and the implementation.

The Interface

The services presented to an end user constitute the interface. In the best case, only the services the end user needs are presented. Of course, which services the user needs might be a matter of opinion. If you put 10 people in a room and ask each of them to do an independent design, you might receive 10 totally different designs—and there is nothing wrong with that. However, as a general rule, the interface to a class should contain only what the user needs to know. In the toaster example, the user needs to know only that the toaster must be plugged into the interface (which in this case is the electrical outlet) and how to operate the toaster itself.

Identifying the User

Perhaps the most important consideration when designing a class is identifying the audience, or users, of the class.

The Implementation

The implementation details are hidden from the user. One goal regarding the implementation should be kept in mind: A change to the implementation should not require a change to the user’s code. This might seem a bit confusing, but this goal is at the heart of the design issue.

Good Interfaces

If the interface is designed properly, a change to the implementation should not require a change to the user's code.

Remember that the interface includes the syntax to call a method and return a value. If this interface does not change, the user does not care whether the implementation is changed. As long as the programmer can use the same syntax and retrieve the same value, that’s all that matters.

We see this all the time when using a cell phone. To make a call, the interface is simple—we either dial a number or select an entry in the contact list. Yet, if the provider updates the software, it doesn’t change the way you make a call. The interface stays the same regardless of how the implementation changes. However, I can think of one situation when the provider did change the interface—when my area code changed. Fundamental interface changes, like an area code change, do require the users to change behavior. Businesses try to keep these types of changes to a minimum, for some customers will not like the change or perhaps not put up with the hassle.

Recall that in the toaster example, although the interface is always the electric outlet, the implementation could change from a coal power plant to a nuclear power plant without affecting the toaster. One very important caveat should be made here: The coal or nuclear plant must also conform to the interface specification. If the coal plant produces AC power but the nuclear plant produces DC power, a problem exists. The bottom line is that both the user and the implementation must conform to the interface specification.

An Interface/Implementation Example

Let’s create a simple (if not very functional) database reader class. We’ll write some Java code that will retrieve records from the database. As we’ve discussed, knowing your end users is always the most important issue when doing any kind of design. You should do some analysis of the situation and conduct interviews with end users, and then list the requirements for the project. The following are some requirements we might want to use for the database reader:

We must be able to open a connection to the database.

We must be able to close the connection to the database.

We must be able to position the cursor on the first record in the database.

We must be able to position the cursor on the last record in the database.

We must be able to find the number of records in the database.

We must be able to determine whether there are more records in the database (that is, if we are at the end).

We must be able to position the cursor at a specific record by supplying the key.

We must be able to retrieve a record by supplying a key.

We must be able to get the next record, based on the position of the cursor.

With these requirements in mind, we can make an initial attempt to design the database reader class by creating possible interfaces for these end users.

In this case, the database reader class is intended for programmers who require use of a database. Thus, the interface is essentially the application-programming interface (API) that the programmer will use. These methods are, in effect, wrappers that enclose the functionality provided by the database system. Why would we do this? We explore this question in much greater detail later in the chapter; the short answer is that we might need to customize some database functionality. For example, we might need to process the objects so that we can write them to a relational database. Writing this middleware is not trivial as far as design and coding go, but it is a real-life example of wrapping functionality. More important, we may want to change the database engine itself without having to change the code.

Figure 2.2 shows a class diagram representing a possible interface to the DataBaseReader class.

DataBaseReader class.

Note that the methods in this class are all public (remember that there are plus signs next to the names of methods that are public interfaces). Also note that only the interface is represented; the implementation is not shown. Take a minute to determine whether this class diagram generally satisfies the requirements outlined earlier for the project. If you find out later that the diagram does not meet all the requirements, that’s okay; remember that OO design is an iterative process, so you do not have to get it exactly right the first time.

Public Interface

Remember, an application programmer can access it, and thus, it is considered part of the class interface. Do not confuse the term interface with the keyword interface used in Java and .NET—which is discussed in later chapters.

For each of the requirements we listed, we need a corresponding method that provides the functionality we want. Now you need to ask a few questions:

To effectively use this class, do you, as a programmer, need to know anything else about it?

Do you need to know how the internal database code opens the database?

Do you need to know how the internal database code physically positions itself over a specific record?

Do you need to know how the internal database code determines whether any more records are left?

On all counts the answer is a resounding no! You don’t need to know any of this information. All you care about is that you get the proper return values and that the operations are performed correctly. In fact, the application programmer will most likely be at least one more abstract level away from the implementation. The application will use your classes to open the database, which in turn will invoke the proper database API.

Minimal Interface

Although perhaps extreme, one way to determine the minimalist interface is to initially provide the user no public interfaces. Of course, the class will be useless; however, this forces the user to come back to you and say, “Hey, I need this functionality.” Then you can negotiate. Thus, you add interfaces only when it is requested. Never assume that the user needs something.

Creating wrappers might seem like overkill, but there are many advantages to writing them. To illustrate, there are many middleware products on the market today. Consider the problem of mapping objects to a relational database. OO databases have never caught on; however, theoretically they may be perfect for OO applications. However, one small problem exists: Most companies have years of data in legacy relational database systems. How can a company embrace OO technologies and stay on the cutting edge while retaining its data in a relational database?

First, you can convert all your legacy, relational data to a brand-new OO database. However, anyone who has suffered the acute (and chronic) pain of any data conversion knows that this is to be avoided at all costs. Although these conversions can take large amounts of time and effort, all too often they never work properly.

Second, you can use a middleware product to seamlessly map the objects in your application code to a relational model. This is a much better solution since relational databases are so prevalent. Some might argue that OO databases are much more efficient for object persistence than relational databases. In fact, many development systems seamlessly provide this service.

Object Persistence

Object persistence refers to the concept of saving the state of an object so that it can be restored and used at a later time. An object that does not persist basically dies when it goes out of scope. For example, the state of an object can be saved in a database.

However, in the current business environment, relational-to-object mapping is a great solution. Many companies have integrated these technologies. It is common for a company to have a website front-end interface with data on a mainframe.

If you create a totally OO system, an OO database might be a viable (and better performing) option; however, OO databases have not experienced anywhere near the growth that OO languages have.

Standalone Application

Even when creating a new OO application from scratch, it might not be easy to avoid legacy data. Even a newly created OO application is most likely not a standalone application and might need to exchange information stored in relational databases (or any other data storage device, for that matter).

Let’s return to the database example. Figure 2.2 shows the public interface to the class, and nothing else. When this class is complete, it will probably contain more methods, and it will certainly contain attributes. However, as a programmer using this class, you do not need to know anything about these private methods and attributes. You certainly don’t need to know what the code looks like within the public methods. You simply need to know how to interact with the interfaces.

What would the code for this public interface look like (assume that we start with a Oracle database example)? Let’s look at the open() method:

public void open(String Name){

/* Some application-specific processing */

/* call the Oracle API to open the database */

/* Some more application-specific processing */

};

In this case, you, wearing your programmer’s hat, realize that the open method requires String as a parameter. Name, which represents a database file, is passed in, but it’s not important to explain how Name is mapped to a specific database for this example. That’s all we need to know. Now comes the fun stuff—what really makes interfaces so great!

Just to annoy our users, let’s change the database implementation. Last night we translated all the data from an Oracle database to an SQLAnywhere database (we endured the acute and chronic pain). It took us hours—but we did it.

Now the code looks like this:

public void open(String Name){

/* Some application-specific processing

/* call the SQLAnywhere API to open the database */

/* Some more application-specific processing */

};

To our great chagrin, this morning not one user complained. This is because even though the implementation changed, the interface did not! As far as the user is concerned, the calls are still the same. The code change for the implementation might have required quite a bit of work (and the module with the one-line code change would have to be rebuilt), but not one line of application code that uses this DataBaseReader class needed to change.

Code Recompilation

Dynamically loaded classes are loaded at runtime—not statically linked into an executable file. When using dynamically loaded classes, like Java and .NET do, no user classes would have to be recompiled. However, in statically linked languages such as C++, a link is required to bring in the new class.

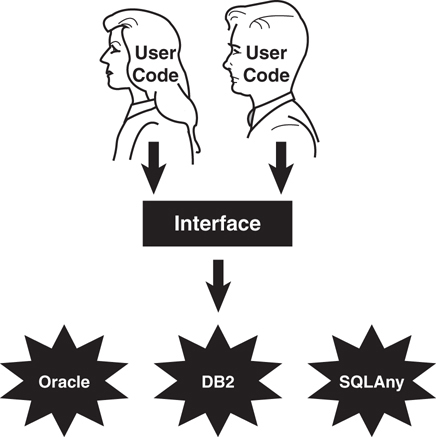

By separating the user interface from the implementation, we can save a lot of headaches down the road. In Figure 2.3, the database implementations are transparent to the end users, who see only the interface.

Using Abstract Thinking When Designing Interfaces

One of the main advantages of OO programming is that classes can be reused. In general, reusable classes tend to have interfaces that are more abstract than concrete. Concrete interfaces tend to be very specific, whereas abstract interfaces are more general. However, simply stating that a highly abstract interface is more useful than a highly concrete interface, although often true, is not always the case.

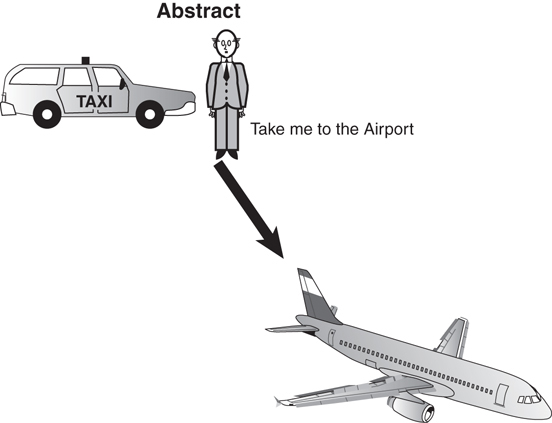

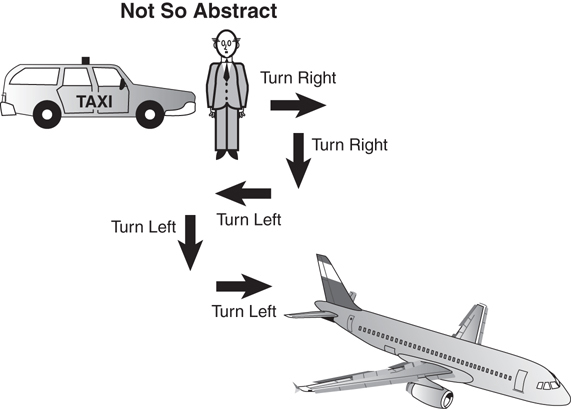

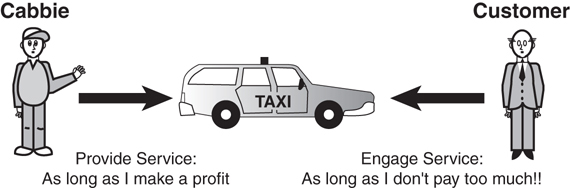

It is possible to write a very useful, concrete class that is not at all reusable. This happens all the time, and nothing is wrong with it in some situations. However, we are now in the design business and want to take advantage of what OO offers us. So our goal is to design abstract, highly reusable classes—and to do this we will design highly abstract user interfaces. To illustrate the difference between an abstract and a concrete interface, let’s create a taxi object. It is much more useful to have an interface such as “drive me to the airport” than to have separate interfaces such as “turn right,” “turn left,” “start,” “stop,” and so on, because as illustrated in Figure 2.4, all the user wants to do is get to the airport.

When you emerge from your hotel, throw your bags into the back seat of the taxi, and get in, the cabbie will turn to you and ask, “Where do you want to go?” You reply, “Please take me to the airport.” (This assumes, of course, that there is only one major airport in the city. In Chicago you would have to say, “Please take me to Midway Airport” or “Please take me to O’Hare.”) You might not even know how to get to the airport yourself, and even if you did, you wouldn’t want to have to tell the cabbie when to turn and which direction to turn, as illustrated in Figure 2.5. How the cabbie implements the actual drive is of no concern to you, the passenger. (However, the fare might become an issue at some point, if the cabbie cheats and takes you the long way to the airport.)

Now, where does the connection between abstract and reuse come in? Ask yourself which of these two scenarios is more reusable, the abstract or the not-so-abstract? To put it more simply, which phrase is more reusable: “Take me to the airport,” or “Turn right, then right, then left, then left, then left”? Obviously, the first phrase is more reusable. You can use it in any city, whenever you get into a taxi and want to go to the airport. The second phrase will work only in a specific case. Thus, the abstract interface “Take me to the airport” is generally the way to go for a good, reusable OO design whose implementation would be different in Chicago, New York, or Cleveland.

Providing the Absolute Minimal User Interface Possible

When designing a class, the general rule is to always provide the user with as little knowledge of the inner workings of the class as possible. To accomplish this, follow these simple rules:

Give the users only what they absolutely need. In effect, this means the class has as few interfaces as possible. When you start designing a class, start with a minimal interface. The design of a class is iterative, so you will soon discover that the minimal set of interfaces might not suffice. This is fine.

It is better to have to add interfaces because users really need it than to give the users more interfaces than they need. At times it is highly problematic for the user to have access to certain interfaces. For example, you don’t want an interface that provides salary information to all users—only the ones who need to know.

For the moment, let’s use a hardware example to illustrate our software example. Imagine handing a user a PC box without a monitor or a keyboard. Obviously, the PC would be of little use. You have just provided the user with the minimal set of interfaces to the PC. However, this minimal set is insufficient, and it immediately becomes necessary to add interfaces.

Public interfaces define what the users can access. If you initially hide the entire class from the user by making the interfaces private, when programmers start using the class, you will be forced to make certain methods public—these methods thus become the public interface.

It is vital to design classes from a user’s perspective and not from an information systems viewpoint. Too often designers of classes (not to mention any other kind of software) design the class to make it fit into a specific technological model. Even if the designer takes a user’s perspective, it is still probably a technician user’s perspective, and the class is designed with an eye on getting it to work from a technology standpoint and not from ease of use for the user.

Make sure when you are designing a class that you go over the requirements and the design with the people who will actually use it—not just developers (this includes all levels of testing). The class will most likely evolve and need to be updated when a prototype of the system is built.

Determining the Users

Let’s look again at the taxi example. We have already decided that the users are the ones who will actually use the system. This said, the obvious question is, who are the users?

The first impulse is to say the customers. This is only about half right. Although the customers are certainly users, the cabbie must be able to successfully provide the service to the customers. In other words, providing an interface that would, no doubt, please the customer, such as “Take me to the airport for free,” is not going to go over well with the cabbie. Thus, in reality, to build a realistic and usable interface, both the customer and the cabbie must be considered users.

In short, any object that sends a message to the taxi object is considered a user (and yes, the users are objects, too). Figure 2.6 shows how the cabbie provides a service.

Looking Ahead

The cabbie is most likely an object as well.

Object Behavior

Identifying the users is only a part of the exercise. After the users are identified, you must determine the behaviors of the objects. From the viewpoint of all the users, begin identifying the purpose of each object and what it must do to perform properly. Note that many of the initial choices will not survive the final cut of the public interface. These choices are identified by gathering requirements using various methods such as UML Use Cases.

Environmental Constraints

In their book Object-Oriented Design in Java, Gilbert and McCarty point out that the environment often imposes limitations on what an object can do. In fact, environmental constraints are almost always a factor. Computer hardware might limit software functionality. For example, a system might not be connected to a network, or a company might use a specific type of printer. In the taxi example, the cab cannot drive on a road if a bridge is out, even if it provides a quicker way to the airport.

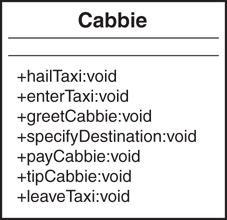

Identifying the Public Interfaces

With all the information gathered about the users, the object behaviors, and the environment, you need to determine the public interfaces for each user object. So think about how you would use the taxi object:

Get into the taxi.

Tell the cabbie where you want to go.

Pay the cabbie.

Give the cabbie a tip.

Get out of the taxi.

What do you need to do to use the taxi object?

Have a place to go.

Hail a taxi.

Pay the cabbie money.

Initially, you think about how the object is used and not how it is built. You might discover that the object needs more interfaces, such as “Put luggage in the trunk” or “Enter into a mindless conversation with the cabbie.” Figure 2.7 provides a class diagram that lists possible methods for the Cabbie class.

Cabbie class.As is always the case, nailing down the final interface is an iterative process. For each interface, you must determine whether the interface contributes to the operation of the object. If it does not, perhaps it is not necessary. Many OO texts recommend that each interface model only one behavior. This returns us to the question of how abstract we want to get with the design. If we have an interface called enterTaxi(), we certainly do not want enterTaxi() to have logic in it to pay the cabbie. If we do this, not only is the design somewhat illogical, but there is virtually no way that a user of the class can tell what has to be done to pay the cabbie.

Identifying the Implementation

After the public interfaces are chosen, you need to identify the implementation. After the class is designed and all the methods required to operate the class properly are in place, the specifics of how to get the class to work are considered.

Technically, anything that is not a public interface can be considered the implementation. This means that the user will never see any of the methods that are considered part of the implementation, including the method’s signature (which includes the name of the method and the parameter list), as well as the actual code inside the method.

It is possible to have a private method that is used internally by the class. Any private method is considered part of the implementation given that the user will never see it and thus will not have access to it. For example, a class may have a changePassword() method; however, the same class may have a private method that encrypts the password. This method would be hidden from the user and called only from inside the changePassword() method.

The implementation is totally hidden from the user. The code within public methods is a part of the implementation because the user cannot see it. (The user should see only the calling structure of an interface—not the code inside it.)

This means that, theoretically, anything that is considered the implementation might change without affecting how the user interfaces with the class. This assumes, of course, that the implementation is providing the answers the user expects.

Whereas the interface represents how the user sees the object, the implementation is really the nuts and bolts of the object. The implementation contains the code that represents that state of an object.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we have explored three areas that can get you started on the path to thinking in an OO way. Remember that there is no firm list of issues pertaining to the OO thought process. Doing things in an OO way is more of an art than a science. Try to think of your own ways to describe OO thinking.

In Chapter 3, “More Object-Oriented Concepts,” we discuss the object life cycle: it is born, it lives, and it dies. While it is alive, it might transition through many states. For example, a DataBaseReader object is in one state if the database is open and another state if the database is closed. How this is represented depends on the design of the class.

References

Fowler, Martin. 2003. UML Distilled, Third Edition. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley Professional.

Gilbert, Stephen, and Bill McCarty. 1998. Object-Oriented Design in Java. Berkeley, CA: The Waite Group Press (Pearson Education).

Meyers, Scott. 2005. Effective C++, Third Edition. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley Professional.