When first designing a service inventory, there are steps that can be taken to ensure that the eventual effort and impact of having to govern the inventory is reduced. This chapter provides a set of patterns that supply some fundamental design-time solutions specifically with the inventory’s post-implementation evolution in mind.

Canonical Expression (275) refines the service contract in support of increased discoverability, which goes hand-in-hand with Metadata Centralization (280), a pattern that essentially establishes a service registry for the discovery of service contracts. These patterns are further complemented by Canonical Versioning (286), which requires the use of a consistent, inventory-wide versioning strategy.

All of these patterns are considered fundamental to inventory governance in that they support and are influenced by the Service Discoverability principle, which actually shapes service meta information in such a manner that it can be effectively discovered and interpreted.

Note

The governance patterns in this chapter focus on fundamental technical and design-related governance issues only. The upcoming title SOA Governance as part of this book series will provide a collection of additional technical and organizational best practices and patterns.

Service contracts delivered or extended by different projects and at different times are naturally shaped by the architects and developers that work with them. The manner in which the service context and the service’s individual capabilities are defined and expressed through the contract syntax can therefore vary. Some may use descriptive and verbose conventions, while others may use terse and technical formats. Furthermore, the actual terms used to express common or similar capabilities may also vary.

Because services are positioned as enterprise resources, it is fully expected that other project teams will need to discover and interpret the contract in order to understand how the service can be used. Inconsistencies in how technical service contracts are expressed undermine these efforts by introducing a constant risk of misinterpretation (on a technical level). The proliferation of these inconsistencies furthermore places a convoluted face on a service inventory, increasing the effort to effectively navigate various contracts to study possible composition design options.

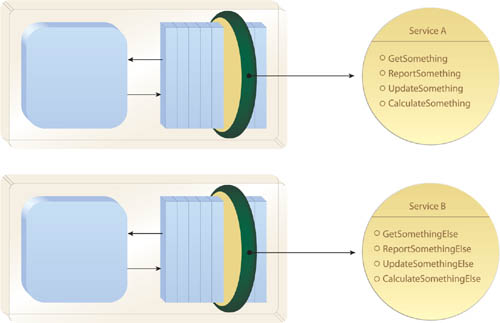

Standardized naming conventions can be applied to the delivery of all service contracts so as to ensure the consistent expression of service contexts and capabilities (Figure 10.1).

A set of naming and functional expression conventions needs to be established as formal design standards. The realization of consistent contract design is then attained via the disciplined use of these conventions within common analysis and design processes.

An example of a standard associated with contract expression is the CRUD (create, read, update, delete) convention traditionally used to outfit components with a predictable set of methods. Entity services in particular often require these types of data processing functions, and using standardized verbs to express them supports the application of this pattern.

With Web services in particular, this pattern will tend to impact the design of WSDL definitions, as illustrated in Figure 10.2.

The relevance of Canonical Expression may at first appear trivial. However, when building a collection of services, especially within larger enterprise environments, a consistent functional expression significantly reduces tangible risk factors.

The primary requirement to successfully applying this pattern is the incorporation and enforcement of the required design standards. If a formal design process has already been established in support of Decoupled Contract (401) and Canonical Schema (158), then the effort to include a step dedicated to Canonical Expression is usually minor.

Note also that unlike Canonical Schema (158), which often must be limited to domain service inventories due to its governance impact, this pattern can more easily be positioned as an enterprise-wide standard. This benefits the enterprise as a whole as consistent expression is established across all domains.

The naming conventions introduced by Canonical Expression influence how several other patterns are applied (as listed at the top of Figure 10.3). This pattern fundamentally supports the goals of Contract Centralization (409) and Metadata Centralization (280) by enhancing the intuitiveness of service identification and reuse.

When growing a service inventory and fostering fundamental qualities such as those realized by Service Normalization (131) and Logic Centralization (136), there is a constant risk of project teams inadvertently (or sometimes even intentionally) delivering new services or service capabilities that already exist or are already in development (Figure 10.4).

This leads to undesirable results, most notably:

• the introduction of redundant service logic, which runs contrary to Logic Centralization (136)

• the introduction of overlapping service contexts, which runs contrary to Service Normalization (131)

• an overall less effective service inventory and technology architecture, bloated and convoluted by the added redundancy and denormalization and in need of additional governance effort

All of these characteristics can undermine an SOA initiative by reducing its strategic benefit potential.

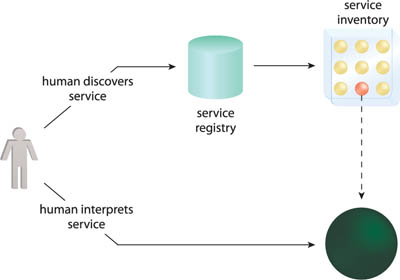

A service registry is established as a central part of the surrounding infrastructure and is used by service owners and designers to:

• register existing services and capabilities

• register services and capabilities in development

As emphasized in discovery-related governance patterns, the registration process requires that discovery information be recorded in a highly descriptive and communicative manner so that it can be used by project teams to:

• locate and interpret existing services and learn about their functional contexts and boundaries

• locate and interpret service capabilities and learn about their invocation and interaction requirements

By providing a current and well-maintained registry of service contexts and capabilities, effective service discovery can be achieved (Figure 10.5).

Note

Metadata Centralization is clearly a design pattern associated with the Service Discoverability design principle and the discovery of services in general. Why then is it not simply called Service Discovery?

Service discovery itself is a process that is carried out once an enterprise has successfully applied Metadata Centralization to its architecture and the Service Discoverability design principle to its services. The process of service discovery is therefore related to a set of SOA governance patterns documented separately in the upcoming title SOA Governance that will be released as part of this book series.

The application of this pattern requires the following common steps:

1. Regularly apply the Service Discoverability principle to all service contracts being modeled and designed.

2. Use service profiles and supporting processes to standardize the documentation of service and capability metadata. For example, a common part of service profiles is a standard vocabulary used for keywords that are attached to the service registry records.

3. Implement a reliable service registry product and position it as a standard part of the supporting infrastructure.

Finally, formal processes for the registration and discovery of services and capabilities need to be established.

Note

This pattern can be applied to a single service inventory or multiple domain inventories, depending on the ability of the service registry product to associate domains with service profile records. For a service profile template and descriptions of service discovery and interpretation processes, see Chapters 16 and 12, respectively, in SOA Principles of Service Design.

Service registration and discovery processes are key success factors for the effective governance of a service inventory. If the processes are not respected or followed consistently by project teams or if the registry is not kept current, then the value potential of Metadata Centralization will severely diminish.

From a design perspective, however, this pattern will introduce the need for metadata standardization, as per the Service Discoverability principle. It will further require that metadata documentation and registration become part of the standard service delivery lifecycles.

There may further be a need to create a new organizational role in support of realizing Metadata Centralization. A person or a group would act as service registry custodian and assume responsibility for collecting the required metadata and maintaining the registry.

Metadata Centralization essentially establishes a service registry, which is key to ensuring the long-term successful application of Logic Centralization (136) and Contract Centralization (409). If the correct services and their contracts can be effectively located (discovered), then the risk of inadvertently introducing redundant logic into an environment is reduced, further supporting Service Normalization (131).

Agnostic services represent the primary type of service for which metadata needs to be centralized for discovery purposes, which is why this pattern is especially relevant to services defined as a result of Entity Abstraction (175) and Utility Abstraction (168).

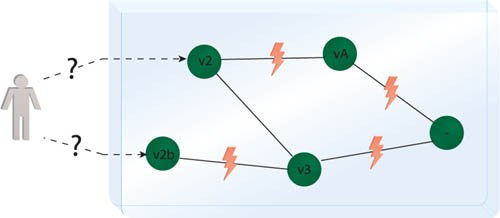

When service contracts within the same service inventory are subjected to different versioning approaches and conventions, post-implementation contract-level disparity emerges, compromising interoperability and effective service governance (Figure 10.8). This can negatively impact design-time consumer development, runtime service access, service reusability, and the overall evolution of the service inventory as a whole.

Service contracts within the same inventory are versioned according to the same conventions and as part of the same overall versioning strategy (Figure 10.9). This ensures a consistent governance path for each service, thereby preserving contract standardization and intra-inventory compatibility and interoperability.

This pattern generally requires that a single versioning strategy be chosen, comprised of a series of rules and conventions that essentially become governance standards.

Canonical Versioning approaches can vary depending on the complexion of the enterprise, existing versioning or configuration management methodologies that may already be in place, and the nature of the overall governance strategy that may have also been established.

There are three common strategies that provide a baseline set of rules:

• Strict– Any compatible or incompatible change results in a new version of the service contract. This approach does not support backwards or forwards compatibility and is most commonly used when service contracts are shared between partner organizations and when changes to a contract can have legal implications.

• Flexible– Any incompatible change results in a new version of the service contract, and the contract is designed to support backwards compatibility but not forwards compatibility.

• Loose– Any incompatible change results in a new version of the service contract and the contract is designed to support backwards compatibility and forwards compatibility.

Note

The terms “backwards compatibility” and “forwards compatibility” are explained in the description for Compatible Change (465) in Chapter 16. For examples of each of these versioning strategies, see Chapters 20–23 in Web Service Contract Design and Versioning for SOA.

There is the constant risk that project teams will continue to use their own versioning approaches, or rely too heavily on patterns like Concurrent Contracts (421), which allows them to simply add new contracts to an existing service.

The successful application of any versioning strategy will require strong support for the adherence to its rules and conventions to the extent that the chosen versioning approach becomes an inventory-wide standard on par with any other design standard. This introduces the need for a new organizational role that is tasked with enforcing the processes and syntactical characteristics that are defined as part of the strategy.

Canonical Versioning essentially formalizes the application of Compatible Change (465), Version Identification (472), and Termination Notification (478), in that the overarching strategy established by this pattern will determine how and to what extent each of these more specific versioning patterns is applied.

The application of Metadata Centralization (280) results in a service registry that enables effective discovery of different contract versions and Canonical Expression (275) implements characteristics in service contracts that improve their legibility. Both of these patterns therefore aid the goals of Canonical Versioning.