Chapter 8. Capturing Social Media Opportunities

The Web is a social medium. As we showed in Chapter 7, the value of content on the Web is directly proportional to the quantity and quality of links to it. To get people to link to your content, you have to establish credibility with folks who share your interests and find your content compelling. To establish credibility, you have to develop relationships with them. Thus, if you hope to create valuable content on the Web, you must frequent the parts of the Web developed for social interaction and sharing. And it is not enough to merely lurk on these social sites. You must contribute. Providing quality social media contributions is a key differentiator between effective and ineffective Web communicators.

Throughout this book, we have used the lens of media determinism to try to distinguish Web communication from other types, especially print. (We defined media determinism in Chapter 2, but perhaps a refresher is in order. Media determinism is the view that what we communicate is at least in part determined by the medium in which we communicate. As Marshall McLuhan is famous for saying, “The medium is the message” [or massage].) The center of the distinction between Web and print writing is links. The social nature of the Web changes the way we write, not just from an information architecture perspective, but from a conceptual perspective. As we showed in Chapter 7, the concept of credibility is similar between print and Web. In both cases, you must get people to refer to your work in order for it to have value. But that is where the similarity ends: Unlike print publications, your Web pages cannot stand on their own. They must have the support of links between your content and complementary content. And that complementary content cannot be just within your domain. Some of those links must be between your domain and collaborators outside of it, in order for them to have sufficient value for Google and other search engines to give your content the visibility it needs. Without search engines ranking your content according to the links to it, your content will not be effective.

Some aspects of social media writing are common to all Web writing: Clear, concise, and compelling content that is relevant to the audience works, no matter where you are on the Web. But in social media, these values tend to be concentrated. In social media settings, clarity, conciseness, and persuasiveness aren’t just values of good writing; they’re necessities. On your own Web pages, a longer piece here or there might be effective for some members of your audience. But you would be utterly ineffective with a longer piece in Twitter, even if its character limit allowed for that. And in social media domains, you don’t just address an anonymous audience of diverse visitors; you engage friends and followers with whom you have developed a relationship. Writing for those particular people requires an even tighter focus on what you want to say. This chapter delves into how and why good Web writing is ever more important in social media settings.

Retrievability—how easy it is for your target audience to find your content—is central to effective Web content. Nowhere is that more important than in social media settings. To make quality social media contributions, you must take advantage of the ways that social media sites use social tagging, visitor ratings, and other social applications to help users with similar interests find relevant content. Still, social media writing is not fundamentally different than writing in other parts of the Web. Effective writing for social media uses the same principles as the search-first writing methods we focused on in previous chapters. For example, writing effective copy so that users will tag it and rank it highly is very similar to writing effective copy for search engines. Here are some important points.

• Social tagging is similar to keyword usage. Social tags are words and phrases that users assign to content. Users can look for particular tags to find what is most relevant to them. Social tagging applications display tagged content to users in innovative experiences such as tag clouds. Obviously, keywords are similar to social tags. They also use words to describe content. Less obviously, perhaps, keywords can also be used in a social way. Search engines pull content related to the keyword clouds that writers use in their content. But writers use particular keywords to attract traffic from folks who are interested in them. Also, when you link to another site, you write the anchor text for those links. Google and Bing pay a lot of attention to the anchor text to assign relevance to links. In this sense, keywords are assigned by the linking sites, just like social tags.

The main difference between social tagging and keyword usage is the person who assigns them to a piece of content. Writers assign keywords to their content. Readers typically assign tags to it. Also, unlike keywords, user tags are displayed onscreen, while search engines use “invisible” keywords to find relevant content to display. Still, the concept of writing with keywords placed in strategic places applies to social Web sites, just as much as it does to your own domain. If you use keywords appropriately, your content is more likely to be tagged by your readers. And when you tag your own content, keywords are the best place to start.

Figure 8.1 shows an example of social tagging at Delicious.com.

Figure 8.1. An example of social tagging in action at Delicious.com. The social tags are listed on the right of the screen shot, with a red box around them. Users can organize their bookmarked content by the tags they assign and share them with like-minded friends.

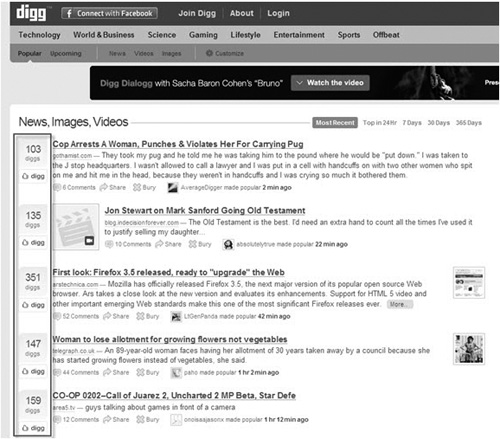

• User ratings are similar to links. Both links and user ratings are votes of confidence for content. But it’s easier for users to vote for content they like using user ratings, because it is a one-click operation. Linking to content is decidedly not a one-click procedure. It often requires at least copying and pasting the link, writing the anchor text, and publishing the content with the link in it. Still, the concept of writing link bait applies in social media settings, just as it does on your own Web domain. Link bait is just highly credible content, whether it appears on your domain or elsewhere. In social media settings, it is more likely to be highly rated. For search engines, links are votes for content. On social sites, “diggs” or “likes” are votes of confidence for content. Perhaps links are better indicators of the perceived quality of content, because of the level of difficulty in “voting” with links rather than by clicking the digg button on Digg.com. But the concept is the same.

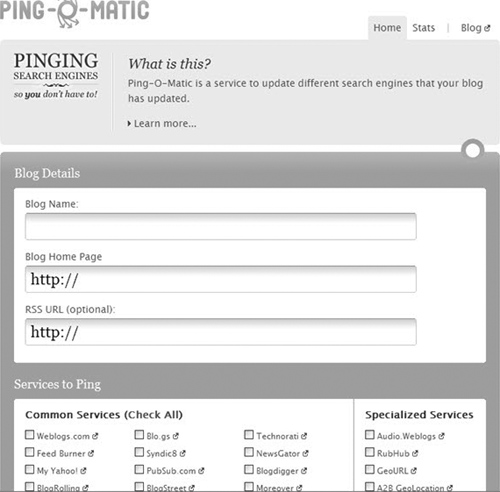

Figure 8.2 shows an example of user ratings at Digg.com.

Figure 8.2. An example of user ratings at Digg.com. Users can click the “digg” link highlighted in the red box to indicate that they like the content. Users will tend to click more often on more popular content.

Some bloggers who write about writing for social media seem to think that social media is very different from ordinary Web writing. Contrary to what we say, these writers claim that some of the basic principles of good Web content don’t apply to social media. For example, Walter Pike writes the following:

Social media is different. It’s different because the reader is in control and the reader is cynical and doesn’t trust spin and brand speak. The reader will participate and comment and, because he or she is connected, will share his or her views with their network. To some it may be bad news but social media is not a fad and it is here to stay. (Source:www.bizcommunity.com/Article/196/16/25990.html)

First of all, we agree with the last line: Social media is here to stay. We expect it to only grow in popularity as time goes on. We also agree that in social media settings, the reader is in control, is cynical, and wants to participate. What we don’t agree with is that these readers’ practices are unique to social media. As we have been claiming throughout this book, the Web as a whole is different from print because Web readers are in control and are more skeptical than print readers. That may be somewhat heightened in social media settings, but it is common in more traditional Web sites. Even before discussing social media, we have encouraged you to enable reader feedback and ratings and other ways for readers to interact with your content. You can do those things just as well on your site as the social media applications do. Yes, social media is here to stay. But social media experiences are not (or should not be) fundamentally different than the Web experiences on your domain. Actually, the only thing we would change about the above quotation is to replace the words “social media” with “Web content.”

Some bloggers take the attitude that writing for social media is different than Web writing to extremes. At www.copyblogger.com/writing-for-social-media, Muhammad Saleem says:

The social media everyman is looking for an entertaining diversion, while being receptive to learning something new if presented in an “edutainment” format that ties the lesson into popular culture.

In the same post as above, he recommends the following headlines for blog posts, which had appeared earlier on copyblogger.com:

• Did Alanis Morissette Get Irony Right?

• The David Lee Roth Guide to Legendary Marketing

• What Owen Wilson’s Pursed Lips Mean to Your Blog

• Don’t Be Cameron Diaz

• What Prince Can Teach You About Effective Blogging

These headlines could not be in more direct conflict with our advice in this book. What’s wrong with them? First of all, just because you’re writing a blog, you shouldn’t throw away everything we taught you about writing descriptive headings that contain the keywords your target audience uses. Users who search on these celebrity names, click through to the results, and land on one of these blog posts, unaware that the blog is actually about writing for blogs, will instantly bounce. Every bounce is a bad user experience and a negative influence on your credibility.

Search is the universal application on the Web, whether the site is a blog or a traditional Web site. All the techniques that we described in Chapters 4 and 5 apply in social settings as well. If anything, they are even more important in social settings, because you have less space in which to do search optimization. Spamming a heading or title tag with irrelevant keywords is wrong everywhere on the Web.

Second, content transparency is central to writing link bait. If you try to pump up traffic volume with misleading headings, no credible source will take you seriously. Using celebrity names to drive traffic to your blog posts is akin to metadata spamming. Search engines will not be the only sites to boot you from their lists of credible sources if you pull tricks like this.

Also, Saleem misses the point of Web audience analysis. The study he cites as suggesting using an “edutainment” format was conducted on a cross section of Web users, some of whom, undoubtedly, cared about the entertainment industry. If your users don’t care about the entertainment industry, using an “edutainment” technique will only turn them off to what might otherwise be good content.

Saleem also cites the study “The Latest Headlines—Your Vote Counts” from journalism.org (http://www.journalism.org/node/7493). However, this study actually comes to radically different conclusions than Saleem seems to think it does. It says that when users vote on content that they find interesting or important in social settings, their votes are highly diverse. In contrast to the mainstream media, they don’t focus on one topic—such as the death of Michael Jackson—to the exclusion of others. In particular, when the mainstream media seems to fixate on one story related to celebrities, the social networks are off taking deeper dives into all sorts of diverse interests in news around the globe. So, far from suggesting that you use the same words or celebrity names as the mainstream press in your social media headlines and tweets, the study suggests that you ignore those words and use ones that connect with the particular needs of your audience.

We cannot emphasize enough just how wrong Saleem is here. If you use the techniques we have outlined in previous chapters and later in this chapter to write relevant content for your Web audiences, you will succeed. These techniques work in both overt social settings and in the less obvious social setting of your own Web domain. Here’s a quick refresher.

• Learn the content needs of your target audience, and use words and phrases relevant to those needs.

• Write your content, starting with the keywords that your target audience members use in their own content efforts (such as search queries, tweets, and blog posts).

• Link in an intelligent way to the most credible content related to your topic, rather than replicating what is already published on the Web.

• Use your own voice to create original content that complements the ongoing conversation on the Web; but only write if you have something original and credible to say.

• Collaborate with credible sources that you have found, to weave your original content into the body of work on a topic, encouraging links from their content into yours.

Social media is a catch-all phrase that is used to describe a variety of Web content models and user interface applications, not all of which fit neatly in any one category. For this reason, beyond our generic advice in previous chapters, our advice regarding writing for social media is geared toward the particular content models and user interface applications within social sites. For example, writing for Twitter is very different than writing for Facebook, though some of the same principles apply.

Social media sites are evolving, and new ones crop up every day. So it is impossible to be all-inclusive in a book such as this. Rather than treating each existing social media site here (that could be the subject of a whole network of sites or series of books), we will focus on a few of the main ones and leave the definitive social media writing guide to some other effort. Applications on which we focus include forums, wikis, blogs, microblogs (such as Twitter pages), and persona sites (such as Facebook and LinkedIn). Other social media sites, such as MySpace, Xing, Google Wave, and Windows Live Spaces, will be left to follow-on work on this book’s companion blog, http://writingfordigital.com.

Social media domains are just sophisticated extensions of the Web. Each domain tries to solve the same problem that search engines have been trying to solve for the general Web: How do you enable Web users to find, share, and consume Web content that is relevant to their interests?

Forums: The Original Online Communities

Forums have been around since before the Web even existed. Before the Web, they resembled online bulletin boards where like-minded users could share information about their passions. For example, when one of the authors of this book (James Mathewson) was in graduate school, he participated in a forum called Rhetlist (now available on the Web at http://blog.lib.umn.edu/logie/rhetlist/), which served a community of educators and scholars interested in the rhetoric of print and online media. At the time, users didn’t come to Rhetlist through the (not-yet-born) Web, but through an online system administered by the University of Minnesota. Almost every academic discipline had a series of forums and discussion lists similar to Rhetlist.

Forums were also adopted by businesses to promote products and enable users to help each other resolve issues with the products. Often, these product-related forums were independent of the vendors themselves and were instead affiliated with Special Interest Groups (SIGs) related to a product or product family. Members of SIGs (which were also known as user groups), often met face to face in addition to participating in the SIGs online. Today, SIGs and other types of user groups still exist, much as they have for the past quarter century, with or without vendor sponsorship.

Among other things, forums were (and are) informal “spaces” where participants:

• Share “inside” information with peers and colleagues

• Form relationships with potential collaborators

• Bounce ideas off of peers prior to publication

• Promote and extend existing publications

Though forums now use the Web as a wrapper application, the basic principles for writing in forums are the same now as they were 25 years ago. First of all, forums are often moderated. Without moderation, participants can veer off topic. Because forums are intended to have a rather narrow topical scope, writers of irrelevant content are often censured, and their work is deleted. Repeated violations can get participants banned from a forum. In today’s blog community sites, participants are also expected to stay “on topic,” though moderation is typically less stringent.

Second, forums are somewhat more insular than a blog community site. New users are encouraged to “lurk” for awhile to get a sense of the topicality of a forum, and its style. After a user has posted fairly regularly, moderators give her more leeway about what she may post. So, for example, you might see an occasional off-topic post by a regular forum participant. When new posters see these off-topic posts, they get the idea that the forum is not tightly moderated, and will sometimes write an off-topic post. When they do this, they are often severely censured.

On forums, it takes quite a few good posts to gain the credibility of the whole community. Before crossing that threshold of credibility, posters must be judicious in contributing. In this regard, writing for forums is similar to other social media venues: The community must show its acceptance of you by responding to your posts with positive comments. Until you have that credibility, your work within forums is limited primarily to reading and making short positive comments on topics. This can be frustrating for those who have important things to say, but whose personas are still relatively unknown. For this reason, building your persona can be as important as writing strong content. Gaining credibility or reputation involves a combination of your body of work and your persona. Your goal in forums is to build that credibility—otherwise known as your reputation.

Of course, credibility is also a common currency in social media settings (and in the Web in general). On the Web, before you can be effective, you need to develop credibility with your audience, and especially with others in your field who will link to your content. In conventional Web sites, it’s a bit more difficult to know when you have the needed credibility. (We showed in Chapter 7 that this is best measured by search visibility and referrals.) In social media settings, you have direct anecdotal evidence of your credibility by the sentiment of the comments that engage with your posts. So credibility might be easier to gauge in social media contexts. But either way, it is a bellwether of Web effectiveness. When you have credibility, all the metrics that we describe in Chapter 9 will start to go in your favor, indicating Web effectiveness.

Wikis: The Purest Form of Web Content

As we mentioned in Chapter 7, Wikipedia is a model for how we recommend that content teams should manage their content, whether within wikis or in other areas. It is very similar to what Tim Berners-Lee envisioned when he developed the Web at CERN: a team of experts collaborating on related content in real time. Somehow, that vision got lost as corporate interests tried to create the Web in the image of print, and to use it as a transaction engine, with good success. But Wikipedia brought back the ideal of the Web as an information management application. It has shown over time the true power of the Web. Wikipedia works by engaging subject matter experts on every conceivable topic and using an army of volunteer editors to ensure the accuracy and completeness of the topics. The integrity of the content process and the credibility of the experts engaged in the project ultimately resulted in Wikipedia taking the top position in Google for hundreds of thousands of keywords.

Of course, Wikipedia is only one of thousands of wikis on the Web. It is just the most comprehensive and recognizable one. Organizations large and small are using wikis as a way to connect internal and external experts on topics of interest. At IBM, for example, we have wikis related to most of our product lines. Because they engage the community in a transparent way, wikis are the fastest growing kind of content in the ibm.com domain in terms of traffic volumes. They also are drawing search traffic away from some of our more traditional marketing pages on the same topics. This challenge is being met by ensuring that the wikis link to traditional Web pages. In this way, we can capture some link juice while providing an interactive form of content to our target audience.

Wikis are not only great vehicles of content for companies, but for individuals as well. If you are an expert on a topic, it is worth your while to try to get content published on Wikipedia related to that topic. To do this, start by commenting on the existing content on that topic and see if you can get approval to fill holes or gaps, as needed. Wikipedia is always looking for helpers to make it an even better free reference. Once you have some content up on Wikipedia, you can link to it and use it as a way to promote your credibility on the topic in other venues, such as your blog or Twitter page.

Wikipedia is not the only place where good writers can make a name for themselves. You can create your own wiki environment on your site, using free tools such as Wetpaint (www.wetpaint.com). These are good ways to publish content that needs frequent updates and regular collaboration from team members who share a topic area. Be careful, though. Because wikis are live environments, they are susceptible to higher error rates. And they can be vandalized, so you’ll need to do daily maintenance. Because of this, they are not necessarily the best option for content that will persist on your environment. But for quick updates around a shell of topics, wikis are great avenues in which to more fully engage with your target audience.

Writing for wikis is somewhat different than writing for Web pages, because you serve as your own architect. You decide when to make a new page within a topic and how to populate it. Unlike more traditional Web environments, where templates typically enforce strict character counts, wikis are much more flexible, expanding and contracting to fit the topic at hand. That said, the temptation is to become overly verbose if you have more room to work with. So you must still write concisely, keeping in mind that Web readers scan before reading and skim otherwise, especially if topics are on the long side.

We said earlier that wikis are the purest form of Web publishing because they fit Tim Berners-Lee’s original Web concept. But there are other reasons. For one thing, wikis are uncomplicated from the standpoint of code and metadata. It is almost impossible to be anything but transparent in them. So our advice about writing genuine link bait by starting with keywords that resonate with your target audience should be a natural consequence of writing for wikis, provided that you learn what your target audience needs. They’re also places that rely heavily on links—not only internal to the wiki, but to external resources. For this reason, link juice is a natural consequence of good wiki architecture. Wikipedia is a great example of how to own topics on thousands of keywords in Google without even trying to do SEO. The integrity of the process virtually ensures it.

Blogging to Grow Your Voice

Blogs are topic-centric sites in which personalities write regular Web columns and encourage participation with regular readers. Blog formats are about as diverse as Web sites, so it makes little sense to form a narrow definition here. But, in addition to conventional Web writing best practices, there are a few features that all blogs have in common, which affect blog best practices.

• Like Web sites, the most successful blogs look for gaps in subject matter. If you find yourself saying the same thing as other more established bloggers, consider a new niche.

• Blogs are personality-driven. As with a column in a newspaper, the writer’s voice and reputation are as important as what he or she writes about in a given day.

• Unlike some Web content, the expectation is for blogs to be updated with fresh content regularly. Most readers will subscribe to your blog using RSS. If they aren’t notified about a new post very often, they might stop clicking through to your blog.

• Also, blogs have regular followers who comment—often multiple times a day—and interact with each other in the comment section. Regular blog commenters can be an important source of interest for your readers.

Each of these aspects of blogs changes the way we think about writing for them. We will delve more deeply into each here.

Find your niche. The easiest way to develop a loyal audience is to provide unique content. Just as you would lurk in a forum (hang out without commenting) and figure out what is both topical and as yet unsaid, follow the blogs on your topic of interest and find out what they’re not talking about. Then fill that gap. Of course, you want to acknowledge how important your work is relative to theirs and develop all kinds of links between your content and theirs. The more tightly you integrate with other experts, the more effective your blog will be.

Unveil your personality. Perhaps the single most important thing about a blog is to bring out your own personality. Building in an occasional personal reference can endear you to your audience. In some cases, even if the personal reference isn’t endearing, it helps to be a somewhat crusty character. Don’t tell your whole story right away or inundate your audience with personal anecdotes. But an occasional personal reference can strengthen the personal connection you develop with your audience.

Keep it fresh. Try to find something to say regularly (we recommend at least weekly), even if once in a while you have a short post or a regular post of all the links you’ve discovered over the course of a week. If you don’t give your audience a reason to come to your page weekly, they will get out of the habit of coming to your site.

Cultivate comments. In a blog, readers’ comments are almost as important as the posts themselves. Regular posters will respond to each other and drive the comments up considerably. There’s no secret to getting people to comment, but it helps to take risks and purposely be controversial. Controversy breeds comments, which lead to more comments. You can have accurate, unique content and it won’t gain many comments because there’s nothing to disagree with. But if you make a few bold statements, some will respond to the controversy and the battle lines will be drawn. Nothing does more to develop a loyal following than to see lively debates in your comment section.

Enable linkbacks. Some blog software, such as WordPress, allows you to track when and where people link to your blog posts. Linkbacks come in several varieties—most notably trackbacks and pingbacks, which are often colloquially referred to as trackbacks. Linkbacks are valuable because they help you monitor the conversation around your writing, and in some cases, engage with those who link to your work to establish a richer content relationship with their work.

The technical details of trackbacks and pingbacks are somewhat complex and outside the scope of this book. If you enable linkbacks on your blog, you will need to carefully manage the spam that inevitably arises from them. Spam bots follow links through the blogosphere to find places to post automated marketing messages, which dilute the effectiveness of your comments. Both types of linkbacks—trackbacks and pingbacks—require you to monitor, delete, and block spammers from using your comment section as a place to tout their nefarious products and services. The extra management effort is well worth it, however, because link information is some of the most important data you can receive about your blog. Linkbacks enable you to monitor and take action and improve your blog’s link equity.

A blog is a big commitment. To do it right, you must be prepared to post something weekly. You need to monitor comments and occasionally respond to a commenter. Be prepared to moderate the comments section and remove spam whenever you find it. Perhaps most important of all, you need to promote your blog, not only through the tactics we outline above, but through other social media venues. Tweet and retweet your blog posts on Twitter. And post new blog updates on your Facebook and LinkedIn pages.

Using Twitter to Grow Your Network

Twitter is a microblogging site that lets users develop a following of folks with common interests. You develop that following by “tweeting” valuable commentary about areas of expertise. People search on keywords in your tweets and eventually follow you because of their interests in those keywords, and especially your reputation in the field.

At the time of writing, Twitter has a low signal-to-noise ratio. By that we mean that a high percentage of Twitter users don’t really get the concept and tweet on things of little interest to their followers. The more tweets from your followers about irrelevant things, the less useful the application is. Your followers can choose to stop following you if you post too much noise. So developing a loyal group of followers forces you to tighten your focus on your area of expertise so that those interested in it will want to follow you, within reason. Just as with your blog, we recommend folding in an occasional personal item of interest to build your persona with your followers. The more followers you have, the bigger your sphere of influence. That sphere of influence is a good measure of your credibility, and an excellent way to promote your content in other Web venues, such as your blog and your Web site.

One of the reasons Twitter users struggle with the application is the strict 140-character limit for tweets. If you try to post a tweet with more than 140 characters, the application will tell you to be more concise. Saying something worth posting in fewer than 140 characters (letters, spaces, and punctuation marks) is a difficult challenge for writers accustomed to having as much space as they need to say what they want. There are three responses to this:

- You can refrain from tweeting because you can’t seem to find the words to say your piece concisely.

- You can feel compelled to write something insignificant or irrelevant because it fits into the 140-character limit and you feel the pressure to tweet daily.

- You can take on the challenge of saying important things in the space provided.

The first response will reduce your roster of followers, as they assume you don’t have anything interesting to say on a regular basis. The second response will cause you to lose followers who grow weary of weeding through noise to get to the signals. The third response will lead to you gain followers. Because Twitter success is measured by the number of followers you have, we will focus on techniques of fitting your insights into the space provided. Optimizing those tweets is a further step that we will cover below.

As Twitter gains popularity, it will change the way people write on the Web. A strict space constraint forces writers to be more concise about every aspect of their writing. They learn to cut needless words out of sentences. They learn to write with more verbs and fewer adjectives. They learn to write in active voice. In short, they learn all the lessons they need to write more concisely in all their Web work, and increase their effectiveness for Web audiences.

First and foremost, concise writing demands that you don’t try to say too much in your tweets. One single thought is all you need. If you have other related thoughts, you can always say them in subsequent tweets. Some writers struggle to reduce their thinking down to elemental insights and focus on one per tweet. If you find yourself really struggling to fit your insight into a tweet, consider breaking it up into two related insights.

Second, you’d be surprised how few words it takes to write a single insight if you edit your work down to size. A good reference for how to do this is Strunk and White’s Elements of Style (1979, 23-4). For example, one very common phrase is due to the fact that; it can be simply replaced with because. Another common problem is putting the adjective at the end of the sentence, although it’s shorter and punchier to put it before the noun. We won’t go into all of the habits of concise writing here. Repeatedly editing your own work will eventually teach you to say more important things with fewer words.

You can reduce the character count in your tweets with some of the application’s functions.

• Use a URL shortener, such as bit.ly (http://bit.ly/) to rewrite the URLs you embed into your posts with the fewest possible characters.

• Use the @ sign before a follower’s Twitter name to show that you are responding to a tweet by one of your followers. This lets you get right to the point of the tweet.

• Use the hashtag (#) function to indicate keyword tags in your tweets. This not only lets you condense your writing by breaking it into its most elemental keywords, but it will help you follow threads of content between tweets. Simply follow @hashtags to have your hashtags tracked. You can follow your hashtags in real time at hashtags.org.

Hashtags are one way to optimize your tweets for search engines, including the Twitter search engine. But they should be used judiciously. Choose hashtags as you would keywords on Web pages: one per page or tweet. Your hashtags should also be part of the network of keyword clouds surrounding your area of expertise. Using keywords and hashtags based on popularity, rather than on relevance to your area of expertise, is akin to spamming. You can attract a lot of followers who are not directly interested in your tweets, and thereby damage your image in the process. Or you can turn off your followers by using hashtags that are not relevant to their interests.

One of the best ways to measure the success of your tweets is by the number of retweets, or tweets that other users embed in their own tweets. Because retweets typically contain a link to the original tweet, they also improve link equity to your twitter page. In his research on the subject, coauthor Frank Donatone discovered several ways to improve the chances that your tweets will get retweeted. Here are the highlights of that research.

• Time of day. If you tweet during normal business hours (EST), you will have a better chance of getting retweeted. You can use the tweetlater function (www.tweetlater.com/) to automate your tweet timing.

• Links. Tweets with links in them are three times more likely to get retweeted.

• Self reference. If your tweets are related to how twitter affects your area of expertise, they will be more likely to get retweeted.

• Timeliness. If you are the first among your followers to tweet on a timely topic, it will be more likely to get retweeted among your followers.

Twitter is a great way to tighten your focus on your target audience by attracting like-minded followers and promoting your content to them. Writing concise, search-optimized tweets is an emerging art form. But the same principles that govern successful SEO in other Web venues apply.

• Use search-optimized titles

• Constrain tweets to one insight

• Tweet in the fewest possible words

• Use a URL shortener, such as bit.ly

• Add a relevant hashtag

• Work to get retweets

If you do these things, you will grow your following and maximize the value of your time spent on Twitter.

Optimizing Your Facebook and LinkedIn Presences

We don’t advocate using Twitter to build your online character. There is little room for writing personal tweets to people who are following your professional persona. For hobbies and other passions outside of your professional persona, we advocate using Facebook. For more involved professional news about you than you can tweet, we recommend LinkedIn.

Facebook is a site that enables you to build a personal profile comprising your full range of interests. It replicates what early Web users tried to do on their own: build a site that encapsulates your values, projects, tastes, friends, and family. You develop a network of friends, who alone can see your posts and poll responses (if you manage your security settings appropriately). And you write short daily posts that call attention to the best examples of these aspects of your character.

LinkedIn is another venue to get your name out there. While Facebook is primarily a place to connect with friends and family, LinkedIn is primarily a place to cultivate professional contacts. There will be some overlap between your LinkedIn connections and your Facebook friends, so the distinction is not sharp. But if you think of the two as serving somewhat different purposes, you can channel your messages to one or the other depending on purpose. For example, if you have an important publication that you want your professional contacts to know about, post an update to your LinkedIn page. If you did something fun or interesting in your personal life, post it to Facebook. Of course you can cross post and even set up feeds from Twitter to Facebook and LinkedIn. But managing three pages and a blog with the kind of intensity that folks display on Twitter can consume more of your time than you have, and you will end up not being able to say anything interesting about yourself.

The value of your Facebook or LinkedIn personas is that they are about trust. If you help your friends and connections understand the breadth and depth of your character and experience, they are more likely to trust your writing in other settings. Of course, both sites are also great places to collaborate and connect with your network. Forming and participating in groups is an essential way to grow your network of friends and connections beyond those you formed through past and present companies you worked for. Actions speak louder than words. Collaborating with friends and connections gives you an opportunity to directly demonstrate that the persona you promote on Facebook and LinkedIn accurately represents what you’re about.

Of course, Facebook and LinkedIn are also great places to promote your Web writing. They enable you to post links to your blog or Web sites when new updates are available. As mentioned, both Facebook and LinkedIn allow auto feed from Twitter (using the #fb and #in hashtags), so that your tweets can be automatically posted on your Facebook and LinkedIn pages for all your friends and professional connections to see. When Twitter followers become Facebook friends or LinkedIn connections, this lets you show that your professional and personal personas are compatible, or even integrated.

Writing in these settings poses some unique challenges. As with Twitter, shorter posts tend to be more effective. Facebook posts with links tend to get reposted by others. Cultivating and writing in your voice is particularly effective when you know your audience well and they know you well. Using the conversational tone that you cultivate in your blog will get more comments than bland or flat text. Finally, although your blog won’t get direct link juice from these mentions, promoting your blog to other bloggers through Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn is the surest way to get them to link to your blog posts. As on other Web venues, link equity is the surest way to drive targeted traffic to your Web content, especially your blog.

At times, Facebook and LinkedIn are less about writing than they are about posting links to videos, photos, and other rich media assets. Sometimes you can say more with rich media than you can with text. For these times, using Facebook and LinkedIn to make your point is the most effective way to connect with your friends and contacts.

Sustainable Practices for the Web as a Social Medium

As we have mentioned, it takes a big commitment to thrive in social media. The temptation is to try to push your name out there and get a lot of friends and followers in a hurry. You can do this, but it might not be the best strategy. Too often, people come to social sites with a lot of energy and later find that they can’t sustain their initial enthusiasm. They get burned out on the daily activities and their blogs, Twitter pages, and Facebook pages are suddenly thin on content.

A lifeless blog with irregular posts is worse than no blog at all. Followers and commenters will stop coming to your social venues when you do not provide regular updates. For this reason, we recommend starting small with a blog, moving to Facebook and LinkedIn pages, and eventually creating a Twitter page. If you gradually ramp up to a rich complement of venues, you can sustain success.

If you take a realistic look at how much time you can devote to the four primary social venues (blogs, Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter), you can develop an integrated social media strategy. The general strategy uses your Web page for persistent content, your blog for daily insights, your Twitter page for condensed insights, and your Facebook and LinkedIn pages for your persona.

A general sustainable content strategy also means not trying to do too much in terms of the topics you focus on. As we showed in Chapter 7, the object is to become a hub of authority on subjects for which you are considered an expert; that prospect depends on making connections with other experts in your field, and rather than trying to compete with them, collaborating with them. Find the white space in their work and fill it with original insights and research. Become the connection point in their work. When you apply this overarching goal to the four social media venues we talk about in this chapter, your task won’t seem so overwhelming.

You will have more success by defining your scope as a hub of authority, where the spokes are your Web audience, blog commenters, Facebook friends, LinkedIn contacts, and Twitter followers. By not trying to own every topic, but letting collaborators do their work and promoting it on your social media venues, your collaborators will give you the credit you deserve in the form of links, and Google will rank your content with the visibility it deserves.

Summary

• Social sites such as blogs, Facebook, and Twitter are just more overtly social than traditional Web pages.

• Social media innovations such as social tags and ratings are similar to keywords and links, respectively.

• Blogging is similar to writing for the Web, except that it’s much more focused on a single topic and on a well-defined audience.

• Pinging, RSS feeds, and participation in social tagging sites are keys to blogging success and SEO.

• Twitter can extend your blog reach by developing a rich group of like-minded followers.

• Facebook can enhance your blog and Twitter persona by letting your friends know about your side projects, values, tastes, friends, and family.

• Integrating the content you publish to these four venues can help you develop a sustainable content model that extends your connections with collaborators.