6. Financing the Developing World

“Like slavery and apartheid, poverty is not natural,” declared Nelson Mandela. “It is man-made and it can be overcome and eradicated by the actions of human beings.” This challenge lies at the heart of development finance, a field that has until recently been largely passed over by financial innovation.

The goal of ending global poverty has proven elusive for so long that it is painful to contemplate the failed efforts and squandered opportunities. But the broader picture is not uniformly bleak. The World Bank reports that the percentage of people around the world living in extreme poverty dropped by half between 1981 and 2005. Half a billion people who once struggled to survive on less than $1.25 a day have been lifted out of poverty in one of the greatest success stories of our times.1

Perhaps the most dramatic strides have been made in China, which just 30 years ago was one of the poorest countries in the world. Since 1990, it has grown at an average rate of more than 10% a year in real terms. In 2008, its $7.9 trillion GDP (adjusted for purchasing power) stood second only to the United States’ (at $14.3 trillion). India, too, has seen sweeping change; since 1990, it has grown at more than 6% a year in real terms. It is now the fourth-largest economy in the world, with a GDP adjusted for purchasing power of $3.3 trillion (trailing the third-largest economy, Japan, which posts a GDP of $4.4 trillion).2

The grip of poverty has been loosened and a new middle class has emerged—not only in China and India, but also in emerging nations such as Brazil, Malaysia, and South Korea. Their trajectories make it clear that the most direct route to poverty reduction is the creation of real, broad-based economic growth that generates jobs. It is no coincidence that the World Bank found the most remarkable strides were made in East Asia. As the region’s economy came roaring to life, ignited by increased international trade, the extreme poverty rate was slashed from nearly 80% to 18% in just 24 years.3

But that progress, heartening as it is, has not penetrated to all the desperate corners of the globe. In places like sub-Saharan Africa, where a dire health crisis hinders productivity, little progress has been made. The proportion of the population in sub-Saharan Africa living on less than $1.25 a day decreased from 55.7% in 1990 to 50.3% in 2005. However, because of population growth, the number of people in the region living in extreme poverty actually grew by 100 million over this period.4

Spurring on the kind of economic growth that can overcome the development gap is the central task of our generation. Traditional foreign aid—disbursement of loans, grants, and other assistance by individual governments or multilateral agencies—is very much focused on issues of poverty reduction and global health; there is no doubt it has a continuing and vital role to play. But a wave of financial innovation is urgently needed to supplement this model and truly integrate developing nations into the global economy.

Growth cannot be sustained by low savings rates, undeveloped financial systems, and inadequate financial intermediation between savers and investors (both locally and internationally). Sound banking systems and transparent markets are the underpinnings of sustainable development. Financial innovators will need to actively participate in the effort to build solid financial institutions and expand access to credit and financial services in order to responsibly fuel higher rates of growth.

In addition to financial infrastructure, the developing world has an overwhelming need for physical and social infrastructure—and vast flows of capital will need to be mobilized to support this effort. Nobel laureate Gary Becker and others have repeatedly shown the importance of human capital investments in determining income, so it is no surprise to see that the earnings of more educated individuals rise faster than earnings of the less educated.5 Dramatically expanding access to education is crucial to ensuring that gains are more widely and equitably shared across entire populations, thus reducing not only the gaps between nations, but internal inequalities as well. Focusing on the factors that could increase human capital productivity (not only education, but inputs such as health, housing, communication, and transportation) will enable the developing world to take advantage of greater trade and inflows of technology and capital.

The dramatic gains against poverty seen in the last three decades could have happened only in a more open and integrated world economy. As the World Bank’s Commission on Growth and Development noted, “Growth is not an end in itself. But it makes it possible to achieve other important objectives of individuals and societies. It can spare people en masse from poverty and drudgery. Nothing else ever has.”6

Table 6.1. Types of Financial Innovations for Development

Paradigm Shifts in Development Finance

Whenever an international summit is convened, or whenever a new American president takes office, wistful memories of the Marshall Plan are invoked as a road map for turning around the developing world. That dutiful policy reference echoes from John F. Kennedy’s “Alliance for Progress,” to George W. Bush’s “Millennium Challenge,” to Barack Obama’s recent calls for new global development initiatives.

Under the Marshall Plan, the United States injected billions of dollars into Europe’s economies to rebuild a continent ravaged by World War II. America’s success in speeding European recovery informed the direction of foreign aid for a generation, as well-meaning officials struggled to apply the same template around the globe.

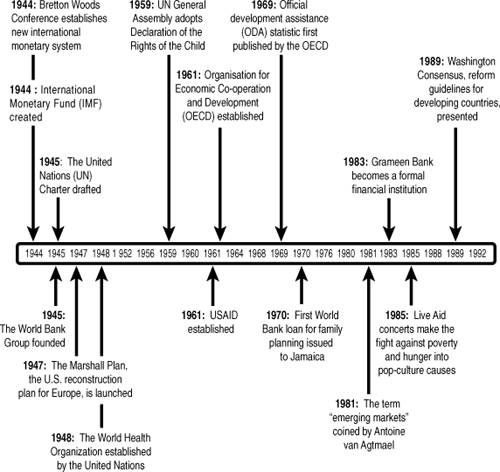

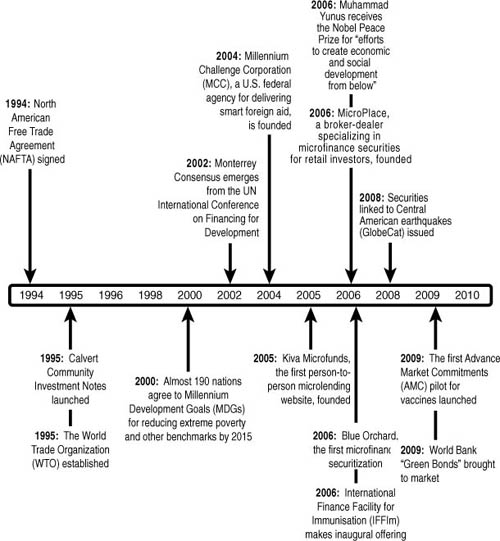

As the timeline at the beginning of this chapter indicates, development finance gained real momentum in the postwar years for a variety of reasons, including a wave of decolonization that led to the independence of countries once under the thumb of European imperialism. The Cold War simultaneously sparked a race between East and West to amass influence and resources in less-developed countries.

This era saw the establishment of a whole range of institutions focused on financing and promoting development as a means to promote stability in the postwar world. These included the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID); KfW, the German development bank; the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD); the World Bank; the International Monetary Fund (IMF); and, of course, the United Nations itself.

The foreign aid disbursed by governments and multilateral agencies in the ensuing decades has been crucial for maintaining some level of health, education, and social services in the poorest countries. But aid alone cannot generate the kind of robust economic growth that is self-sustaining and transformative. Financial innovation is needed to step into the breach and devise new models that can supplement the role of foreign aid.

In fact, by the early 1990s, private capital flows began to outstrip bilateral and multilateral flows of government development funding.7 This signaled a profound shift in the world economy, opening new possibilities for broad-based job growth.

A crucial change in terminology played a supporting role in attracting this new surge of investment. For many years, the “underdeveloped” label had tainted the assets of developing nations, yielding undervalued assessments and arbitrary discounts. But terms like “less developed countries (LDCs)” and “Third World” eventually gave way to “newly industrialized countries (NICs).” Then, in the early 1980s, Antoine van Agtmael, then serving as division chief for the World Bank’s treasury operations and deputy director of the International Finance Corporation’s Capital Markets Department, coined the term “emerging markets.”8

This new definition proved to be a masterstroke of marketing. Now developing nations had a designation that reflected their economic potential and the investment opportunities they presented. Just two and a half decades after this nomenclature change, The Economist would declare, “The world is experiencing one of the biggest revolutions in history, as economic power shifts from the developed world to China and other emerging giants. Thanks to market reforms, emerging economies are growing much faster than developed ones.”9 Today emerging markets are poised to account for a majority of global GDP.10

It’s clear that some major battle lines have shifted in the fight against global poverty. But the gains have not been shared equally, and billions of people have yet to see their standard of living improve. The challenge for today’s financial innovators is to find a way to replicate the unprecedented achievements of the last three decades more widely.

A Marshall Plan for Africa, parts of Latin America, the poorest regions of Asia, and the non-oil-producing Middle East is simply not in the offing from Western nations. In 2000, the world’s leaders set out an ambitious agenda for development at the United Nations. The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were formal pledges to eradicate extreme poverty and hunger, provide universal education, improve child and maternal health, and combat HIV/AIDS, among other worthy aspirations. It does indeed appear that the initial targets for reducing extreme poverty will be met by 2015, but the larger agenda is in doubt.

A 2002 study by the World Bank estimated that an additional $40 billion to $70 billion in additional assistance per year would be needed to meet all the MDGs.11 In the wake of the global financial crisis, few donor nations are in a position to increase foreign aid. In 2009, a UN task force reported that donors are falling short by $34 billion per year on pledges made at the 2005 G-8 meeting in Gleneagles.12

Interestingly, in China, there have been calls for the country to use up to $500 billion of its $2.3 trillion foreign exchange reserves in a Chinese “Marshall Plan” to lend money to Africa, Asia, and Latin America. The idea is to help increase living standards in these parts of the world while simultaneously increasing demand for Chinese products.13

But is a simple increase in foreign aid the answer? After many decades and trillions of dollars in foreign aid, donors and emerging-market countries alike have understandably come to question the conventional approaches. Yes, foreign aid eases short-term macroeconomic shocks, alleviates humanitarian emergencies, and provides critical health and education services. At its best, it can build the infrastructure that makes further progress possible. But the best-case scenario isn’t always how things play out.

The traditional model of foreign aid comes laden with baggage: the crushing debt burden of repayment, the frequency with which corrupt officials divert funding away from its intended purposes, the unpredictability of funding flows from donor nations, the stifling of innovation, and concerns over building a culture of dependency. There has been a growing realization that aid cannot be fully effective in the absence of strong institutions and a commitment to transparency in recipient nations.14

Looking beyond foreign aid, the usual economic development palliatives are not up to the task. Foreign direct investment flows are not high enough to drive aggregate demand and growth, and portfolio capital flows to many developing and frontier markets are at a trickle due to insufficient banking institutions and capital market development. Sovereign debt reduction all too often benefits the entrenched elites and does not translate into real infrastructure improvements for the poor. Microcredit, which seeks to provide small-scale entrepreneurial financing to the poorest of the poor, has been widely heralded as a fresh approach. But it is not the panacea that was once envisioned: It still has limited penetration in many neglected regions and, while alleviating poverty to some extent, can never drive economic growth to the levels required to build a global middle class. Some critics are beginning to call its effectiveness into question.15

This is the point at which financial innovation has to enter the game. Capital is urgently needed for vast new infrastructure projects and for funding the small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs) that are the leading engines of job growth. In addition to helping developing nations build banking systems and institutional frameworks, a major challenge is achieving “financial inclusion”—that is, expanding access to credit and financial services to previously excluded populations.

These are perhaps the most sprawling and complex challenges that have ever faced financial innovators, and creative strategies to address these issues are just beginning to emerge. Finding the right answers may involve years of trial and error, but success will unlock the kind of growth that may one day eliminate the need for interventions. With the right tools and capital structures in hand, private investors can open new markets, igniting broadly shared and sustainable prosperity by harnessing the power of entrepreneurial and infrastructure finance.

Building Financial Infrastructure, Building a Middle Class

Empirical studies using cross-country analysis have shown the strong relationship between finance and growth.16 In comparing the financial systems and structures of both developed and developing countries, and considering their impacts on economic performance, a number of important recommendations emerge:

• It is crucial to prudently develop a diversified financial system.

• State banks should be privatized, and foreign banks should be allowed to acquire domestic banks.

• Developing countries should promote a financial system that allows for dispersed private ownership of all financial resources.

• Banks should not be prevented from adopting the latest information technology.

• Governments should provide an appropriate legal, regulatory, enforcement, and accounting environment for financial markets.17

In many emerging markets, systemic and institutional problems constrain growth and hinder broader participation in the economy. Financial power may be concentrated within a tiny elite circle, or a nation may lack property rights, a well-developed legal system for enforcing contracts, market transparency, and good corporate governance.18 These obstacles make the tools of financial technology inaccessible in large parts of the world and have aborted market changes in many countries. Building market and regulatory institutions and capabilities is a critical ingredient of real economic development.

In addition, development officials need to employ tools for screening out high-risk borrowers in advance (thus overcoming adverse selection) and protecting their repayment prospects once borrowers have the money from investment (preventing moral hazard).24 Weak accounting standards, limited third-party credit information services, restrictions on the use of physical collateral, the high cost of managing smaller transactions and projects, and the difficulty of mobilizing a continuing supply of funds are among the issues facing the field of development finance.25

Advances in information technology are beginning to change this picture. Today, it is easier than ever to enable the free flow of accurate operating and financial information to provide oversight by investors, owners, and regulators. But financial technology has its enemies. Entrenched oligarchies in many developing countries have yet to support reforms that might decentralize political and economic power to transform state-run economies into entrepreneurial ones.

A recent study by Asli Demirguc-Kunt and Ross Levine shows how improvements in credit markets and the development of a solid financial infrastructure can translate into economic opportunity:

[A]ccess to credit markets increases parental investment in the education of their children and reduces the substitution of children out of schooling and into labor markets when adverse shocks reduce family income. Moreover, a growing body of evidence suggests that better functioning financial systems stimulate new firm formation and help small, promising firms expand as a wider array of firms gain access to the financial system. Besides the direct benefits of enhanced access to financial services, research also indicates that finance reduces inequality through indirect, labor market mechanisms. Specifically, cross-country studies, individual-level analyses, and firm-level investigations show that financial development accelerates economic growth, intensifies competition, and boosts the demand for labor, disproportionately benefiting those at the lower end of the income distribution.26

Even countries that witness an overall credit expansion due to increased multilateral foreign aid and investment flows will not experience real growth unless there is broader access to banks, formal financial institutions, and credit markets. There is considerable evidence that as the depth and breadth of financial markets increases, an accelerated level of global economic growth follows. Reduced inequality, development, and the operation of the credit markets are clearly linked.27

The Microfinance Revolution

In 1976, an entirely new model of development finance emerged not from Washington’s halls of power, but from the forgotten back streets of Jobra, an impoverished village in Bangladesh. Abandoning his classroom, Muhammad Yunus, a professor of economics, ventured out to meet directly with the poor and learn exactly what factors kept them from earning their way out of poverty. He soon realized that their lack of access to credit left them at the mercy of unscrupulous loan sharks. Moved by their plight, he opened his own purse strings and loaned $27 to 42 women who made bamboo stools. In the process, he launched the microlending movement, taking a more grassroots approach than the traditional top-down aid model.

By 1983, Yunus had founded Grameen Bank as a formal financial institution. It offered small loans to the poor with no collateral required. The bank successfully employed a group lending model, which holds borrowers accountable to their neighbors for repayment performance. Grameen proved that the poor were indeed creditworthy; in fact, the bank boasts that its loan recovery rate is 97.66%. It has enjoyed phenomenal growth: It works in almost 85,000 villages, has served almost 8 million borrowers, and has disbursed US$8.4 billion since its inception. Grameen is 95% owned by its borrowers, most of whom are poor women, and is now completely self-sustaining through the deposits of its customers.28

Appearing at the 2008 Milken Institute Global Conference, Yunus explained the thinking behind his model. “It is amazing how financial institutions reject such a large number of human beings on this planet, saying they are not creditworthy. Instead of banking institutions telling people they’re not creditworthy, the people should tell the banks whether they are people-worthy,” he said. “The basic principle of banking is the more you have, the more you can get. We reversed it. The less you have, the higher priority you get.”29

Grameen’s success inspired a host of other organizations to try microlending—and soon the model expanded beyond the provision of small loans to become microfinance, which encompasses a whole range of financial services for the underprivileged. These include savings accounts, investment products, money transfers and remittances, bill payment services, home loans, education and consumer loans, agricultural and leasing loans, life insurance, property and crop insurance, health insurance, and even pension products—services that were once completely out of reach for disadvantaged populations.30

It is difficult to get an accurate read on the size of the industry worldwide, but it is estimated that anywhere from 1,000 to 2,500 microfinance institutions (MFIs) serve some 67.6 million clients in over 100 different countries.31 Of these 67 million, more than half come from the bottom 50% of people living below the poverty line. That is, some 41.6 million of the poorest people in the world have been reached by MFIs.32

MFIs can take many forms, from NGOs (nongovernmental organizations) and rural development banks to commercial banks. Some MFIs attempt to increase their social impact by tying in additional services such as health and education. While many operate with a purely altruistic mission, others have a for-profit model, with service to the poor as only a secondary goal—a shift that has caused controversy within the microfinance community.33

Beyond Microfinance: The Missing Middle of SME Finance

If there is a lesson from General Marshall’s playbook, it is that the entrepreneurial growth that saved both postwar Europe and the post-Depression United States was fueled by small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs). Even today, this entrepreneurial sector contributes 57% of total employment and more than half of GDP in high-income countries. But the same growth dynamic has yet to be set in motion in low-income countries, where SMEs account for only 18% of employment and 16% of GDP.40 Ironically, development finance is available for microenterprises and large businesses, but not for this “missing middle,” which would actually have the potential to solve the development conundrum if the proper momentum were put behind it.

While microcredit is at an all-time high for individual entrepreneurs and artisans, the funding to expand and thrive is scarce for growth-oriented firms of 10–300 employees in emerging markets. SMEs typically require financing amounts between $10,000 and $1 million, with $3 million to $5 million being the upper threshold. They also need patient capital that gives them time to grow, but many investors are not willing to lock up their funds for extended periods. In recent World Bank Enterprise Surveys, more than 40% of entrepreneurial firms in low-income nations reported lack of capital access as their key barrier to growth.

Although they will provide retail services to these companies, commercial banks tend to avoid lending to this sector, preferring instead to allocate capital to more established companies. (Because banks in many emerging nations enjoy monopoly status, they can afford to ignore market segments such as this and still remain profitable.) Even if they will lend to SMEs, banks tend to impose such stiff requirement for posting collateral that loans are out of reach for fledgling businesses. While 30% of large firms use bank finance in developing countries, only 12% of small companies do. Less than 10% of SME demand for credit is being met by banks facing new Basel II regulations; these institutions often impose requirements of 100% collateral in liquid assets, real property, and cash deposits. In Cameroon, the minimum deposit for opening a checking account is more than $700, an amount higher than that country’s per-capita GDP.41

External financing is also hard to come by, since few angel investors, venture capitalists, or private equity investors—the funders who specialize in startups—operate in these markets. Not only is credit and risk appraisal difficult for investors, but, above all, these markets tend to be illiquid; the difficulty of exiting investments remains perhaps the most formidable barrier to establishing a more substantial flow of foreign capital to this sector. Government and donor-directed subsidized credit programs in support of SMEs have had limited impact in the absence of wider systemic reforms and are fraught with moral hazard and adverse selection problems.

SMEs in the developing world continue to face unique and enormous challenges: barriers to market entry, expensive and time-consuming regulatory requirements, burdensome tax and legal structures, lack of management experience, labor market rigidities, and, above all, limited access to affordable capital (whether traditional bank lending or risk capital). Large firms that enjoy limited competition may influence the regulatory, legal, and financial conditions to block new entrants. Indeed, SMEs face greater financial, legal, and corruption obstacles than large firms, and these challenges constrain the growth of SMEs to a greater degree.42

Are there models for filling the financial service gap for SMEs? How can we identify and assess SME deal flow? What investment structures will enable credit enhancement and flexibility for SMEs on a revolving basis? What would those hybrid capital structures for development investment look like if scaled? How can multilateral and bilateral agencies manage sources of risk for such longer-term investments? What role can developing world stock exchanges play in intermediating capital for SMEs? These are all questions that can be answered with financial innovations.

There are several important barriers that impede the flow of capital to emerging-market SMEs43:

• Exiting investments is difficult. Because emerging countries typically have underdeveloped capital markets and a shortage of buyers, it can be challenging to exit equity investments. Investors are often forced to hold on to these investments longer than would be ideal as they struggle to find a buyer or wait for the entrepreneur to come up with enough cash to buy out the investors’ shares. All else being equal, the longer an investment’s length, the lower the overall return, so the difficulty of exiting discourages investors from putting their money in these markets.

• SME investment returns are not fully risk-adjusted. Due to the lack of solid information, fund managers seeking to invest in this arena are forced to spend a great deal of time and effort locating prospective investments and becoming familiar with companies’ financials. Post-investment, SMEs often require a significant amount of technical assistance from fund managers to improve their businesses. As a result, these types of investments are time- and capital-intensive, leading investors to seek a higher risk-adjusted rate of return. These commercial investors tend to put their money elsewhere or move up-market to more profitable investments at the larger end of the SME continuum. Historically, the vast majority of capital in SME funds has come from multilateral and bilateral development finance institutions. Funds need to find ways to attract more private investors to small and growing businesses.

• Information gaps exist between investors and SMEs. Development institutions and national governments use widely varying definitions of what constitutes an SME, resulting in a lack of comprehensive and comparable data for the sector that makes it difficult for investors to accurately assess opportunities. Investors are hesitant to embrace a sector for which there are no established norms for performance, while entrepreneurs do not have an efficient way of tapping into funding sources. Clearly, there is a need to better connect the two sides to facilitate investment in these markets. Innovations in information technology—such as data reduction and storage technologies that can better index, store, and retrieve small business data sets—may present an opportunity to facilitate a more efficient flow of information in these markets.

There are a range of financial innovations that could start to address these problems. Given the difficulty of exiting investments in developing countries, creating exit finance facilities would be one possibility. In this case, a revolving loan fund could facilitate exits by providing entrepreneurs and other buyers access to capital in the absence of bank funding. Another strategy would be the creation of permanent capital vehicles, comparable to a limited-life fund, which would decrease fund costs and offer liquid shares to investors, making exits easier.

A royalty model could also ensure returns. Investors would have a claim on a percentage of an SME’s sales or revenues over the life of the investment, enabling them to pull in a regular source of capital; in the case of a management buyout, it would decrease the amount that the recipient has to pay at the end of the investment.

Increasing investment through the creation of regional funds or funds of funds has the potential to broaden the investment target and decrease administrative costs relative to investment income, lifting net returns. Increasing the number of technical assistance funding sources and having them operate side-by-side with investment funds would separate technical assistance and boost returns for investors. The use of structured finance vehicles could broaden the investment base in SME firms, enabling different investors to use investment products that suit their risk appetite and return expectations, thus allowing more investors to participate in funding this sector. Another innovation might be first-loss credit enhancement or guarantee funds from local banks that would incentivize them to provide capital to SMEs, thereby capping downside investor risk.

Underlying all these financial innovations would be a greater use of information technology to overcome information asymmetries about these firms and increase investors’ comfort level in dealing with them. This information infrastructure could be essential. It would allow the matching of investors and entrepreneurs, thus increasing the number of SMEs financed and decreasing the costs of sourcing deals. High-level financial and performance data on SMEs would enable investors to make more informed investment decisions.

The global aid architecture is evolving, with an increased role for NGOs, foundations, and private-sector entities—and some organizations are applying alternative and entrepreneurial strategies to SME development. There is an interest in creative approaches to helping SMEs gain access to forms of financing that will free up working capital for business expansion.

For-profit firms like the U.S.-based Microfinance International Corporation are mobilizing remittance flows (personal flows of money from migrants to family and friends still residing in their home country) for capital investments in small enterprises. (The importance of remittances as a source of development aid and investment has increased from $50 billion in 1995 to over $229 billion in 2007.49) Organizations like Small Enterprise Assistance Funds (U.S.) have defined a niche by packaging risk capital with specialized technical support for SMEs.

Others are finding ways to lower the risk premium associated with small businesses. The German bank ProCredit is training loan officers to work directly with small enterprises to manage credit risk and encourage traditional banks to enter the SME sector. The JSE Securities Exchange in South Africa has created an alternative exchange for small enterprises that provides business training for SME executives.

Public- and private-sector actors are exploring how they might underwrite an international bond for SMEs. Some are experimenting with new kinds of financial instruments (debt, equity, and quasiequity) tailored to the credit/risk profile of SMEs.50

A growing number of “impact investors” (see the accompanying sidebar) are now putting their money in organizations that finance the “missing middle.” For example, Small Enterprise Assistance Funds (SEAF) has found that investing in SMEs with high growth potential can deliver not only substantial financial returns, but also social impacts such as increased employment opportunities for the poor; on-the-job benefits such as training and health insurance; low-cost, high-quality goods and services for customers; greater sales opportunities for suppliers; and increased tax revenues to the government. SEAF estimates that for every dollar invested, an additional $12 is generated in the local economy, on average.51

SMEs are widely recognized as key contributors to employment, innovation, productivity, and economic growth. If barriers to its growth were removed, this sector would contribute to expanding the middle class. Achieving a critical mass of SMEs helps to build supply chains and forge dynamic business clusters linked to global markets through trade and investment.

Financing Infrastructure Development

Infrastructure is the lifeblood of any modern economy. No country has sustained rapid growth without also keeping up impressive rates of public investment in infrastructure, education, and health.52 Roads, railways, airports, and seaports are vital for transporting goods, while telecommunications networks form a bridge to the ideas, markets, and technologies available in the broader global economy. Infrastructure spending also encompasses electricity, quality schools, sanitation, and clean drinking water—services that have a dramatic impact on the quality of life for residents of low-income nations.

But for decades, gaps in infrastructure have hampered growth prospects. Traditional foreign aid is too scarce to meet the developing world’s immense and urgent need for investment.

After the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997–1998, infrastructure investment collapsed in the region and has never recovered. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) estimates that over the next decade, Asian governments need to spend $8 trillion at the national level and $290 billion on cross-border projects to integrate the economies of the region; it believes these outlays could generate $13 trillion in real income gains. Emphasizing that returns on telecommunications, energy, and transportation spending far exceed those of other types of spending, the ADB noted that “the inadequacies of Asia’s infrastructure networks are a bottleneck to growth, a threat to competitiveness, and an obstacle to poverty reduction.”53

Two of the world’s fastest-growing economies have taken different paths to modernizing their infrastructure. China has built vast public works in recent years—and its response to the global downturn was not to scale back investment, but to consolidate recent gains. In November 2008, Chinese leaders announced a major stimulus package, with $450 billion earmarked for ports, airports, bridges, schools, hospitals, highways, and roads.54

But in India, where cities are similarly bursting at the seams, the infrastructure is crumbling. Not only is investment inadequate, but corruption and bureaucracy make projects difficult to execute. One adviser to India’s Planning Commission estimated that the nation’s economic losses from congestion and poor roads alone amount to $6 billion a year. The agricultural sector is hampered due to a lack of roads to and from the fields, while employees of multinational companies cannot commute to work due to urban congestion. The “infrastructure deficit” is so dire that it could prevent India from achieving the prosperity that finally seems to be within reach.

In one hopeful sign, India passed a new law in 2005 allowing public–private partnerships for infrastructure initiatives. The first such project was an urgently needed international airport for Bangalore. Siemens participated in building the facility, which will be managed by Switzerland’s Unique Ltd; both companies are equity investors. The state contributed just 18% of the cost, and ownership will transfer to the state after 60 years. The airport opened in 2008, and it is hoped that it will be a precursor for other creative partnerships that can provide a solid foundation for India’s burgeoning economy.55

The situation is also urgent in Africa—especially in sub-Saharan Africa, where road density, electricity, and sanitation lag far behind that of other countries. Only one in four Africans has access to electricity, and only one in three rural Africans has access to an all-season road. According to the World Bank’s Africa Infrastructure Country Diagnostic (AICD), Africa’s infrastructure deficit is lowering the continent’s per-capita economic growth by 2 percentage points each year and reducing the productivity of firms by as much as 40%. By 2007, external financing for infrastructure (from private capital flows, development assistance, and other sources) had reached $20 billion. But the AICD report estimates that some $80 billion a year is needed.56 (Interestingly, as trade has increased between China and Africa, Chinese investment in African infrastructure has scaled up rapidly in recent years. More than 35 African nations have engaged in infrastructure financing deals with China in recent years, including projects for hydroelectric power generation and railways.57)

Funding for infrastructure development around the world became even more scarce in the wake of the financial crisis of 2008. In response, the World Bank and the International Finance Corporation (IFC) created an “infrastructure crisis facility” to provide roll-over financing and help recapitalize existing, viable, privately funded infrastructure projects in financial distress. The IFC announced plans to invest $300 million over three years and mobilize between $1.5 billion and $10 billion from other sources.58

A number of financial innovations could be applied to address this daunting capital gap. Credit enhancement funds could be created to accelerate interest in capital structures, reducing the risks for private-sector investors in these projects. Developing nations could direct more domestic funds to infrastructure projects by using derivatives to free up the allocation of funds from institutional investors, such as insurance companies and provident funds. Measures could be taken to enhance the role of banks as intermediaries for local infrastructure finance projects by creating instruments and markets to shape risk, maturity, and duration.59

One financial innovation has recently been deployed to spur sustainable infrastructure development that fights climate change: World Bank Green Bonds. In partnership with a consortium of investment banks, the World Bank raised $350 million via several key Scandinavian investors (first transaction) and $300 million via the State of California (second transaction) to support green development projects. These include solar and wind installations, deployment of clean technology, upgrades of existing power plants, funding for mass transit and residential energy efficiency, methane management, and forestry protection initiatives administered by the World Bank in developing countries.60

Engaging the capital markets more broadly for infrastructure funding is a major challenge—especially when it comes to tapping the large pools of capital managed by institutional investors such as pension funds; these entities must invest conservatively to carry out their fiduciary duties. Public-sector risk-mitigation programs that might make projects more attractive to these investors are often cumbersome and expensive because they are applied on a case-by-case basis and lack a systematic approach. The concept of “global development bonds” has been floated to overcome the historical inability to link institutional investors with developing countries. These fixed-income securities would cover a pool of diversified projects and would mobilize capital market funding, particularly from U.S. institutional investors. Institutional investors are currently unable to invest in such projects because rated securities do not exist, but this could be solved through public agency and philanthropic credit enhancement. It may be possible to utilize entities like the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) to provide credit wraps or guaranteed credit enhancement funds to draw institutional investors into these infrastructure projects.

Financial Innovations to Enhance Food Security

Much of this chapter has discussed long-range plans to support economic growth and build a global middle class. But the reality is that famine, wars, and natural disasters will always be with us—and with the advent of global warming, we are likely to see more frequent and more severe humanitarian crises.

Global food security remains one of the paramount concerns of our time. One billion people go hungry each day.61 In the developing world, approximately 200 million children under the age of five suffer from stunted growth due to malnutrition, which also plays a role in one-third of all child deaths in this age group.62 And the cost of hunger from medical costs, lost productivity, and lower educational attainment is estimated at $500 billion to $1 trillion over a generation’s lifetime.63

Organizations providing humanitarian food assistance—including international relief agencies, national governments, and nongovernmental organizations—provide one of the few lifelines available to the hungry. But these aid groups face significant challenges to obtaining and quickly delivering food in a cost-effective, efficient, and responsive manner. When commodity prices spike, as they did in 2008, critical weaknesses are revealed in the food assistance supply chain.

Meeting these growing needs in a climate of volatile prices and supply will require improved risk management and more predictable, flexible funding for food assistance organizations. As the G-8 nations discussed in July 2009, strategies for improving food security must focus on strengthening long-term agricultural development, emergency food assistance, and safety-net and nutrition programs.

Humanitarian groups face a multitude of obstacles. Because they rely on voluntary contributions, the timing and volume of funds available can be unpredictable. And many donors place restrictions on how and where their funds can be used. Predictable and flexible capital is necessary to ensure that organizations can maximize their limited resources—and financial innovations can fast-track solutions that will strengthen the food-access pipeline.64

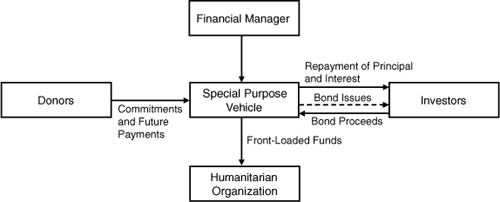

The most intriguing possibility for humanitarian groups involves raising money through the bond markets. If a group of donors made legally binding commitments to a food assistance organization, rated bonds could be issued. A third party could act as financial manager, and credit enhancement could be provided by foundations.

Figure 6.1 outlines the proposed structure for a food assistance bond. A special-purpose vehicle (SPV) would issue bonds backed by donor commitments. The proceeds from the bonds would be transferred to a humanitarian organization. Because the money required for humanitarian relief varies from year to year, the bond proceeds could be based on the amount the organization regularly receives each year. (Emergency needs could still be funded through specific appeals when a crisis occurs.) Investors in the bonds would receive their principal plus interest. A separate entity, possibly the World Bank, would act as financial manager for the transaction. Such a structure requires a credit rating, which poses a challenge if the issuing organization does not have one. In such cases, another organization would have to back the transaction.

Figure 6.1. How a food assistance bond would work

Source: Milken Institute

Bonds could provide a portion of an organization’s funding up front, giving it a clear budget picture and the ability to react immediately instead of waiting for donations to arrive after a crisis is announced, potentially saving more lives. In addition, up-front funding would benefit countries where the timing of delivery is important (in many nations, for example, it is extremely difficult and expensive to move food during the rainy season). The most sensible approach—particularly in Darfur and some other isolated areas—is to collect about 90% of the year’s food supply by April. Proceeds from food-assistance bonds would allow this up-front purchase, and bond proceeds would likely have fewer restrictions than donations from individuals.

This model builds on an example we will examine in the next chapter on financing cures: the International Financing Facility for Immunisation (IFFIm), which secures funding for vaccines. An analysis of the IFFIm funding structure predicted it would increase the health impact of spending on vaccines by 22%, even after taking into account the costs of private-sector borrowing.65 In the case of the IFFIm, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (part of the World Bank) manages the bond proceeds, tracks liquidity to meet disbursement commitments, and services the debt. The bank monitors leverage to ensure that the IFFIm meets all its long-term financial obligations. The IFFIm had a long-term rating on its bonds of AAA from Standard & Poor’s as of July 2009.66

Food-assistance organizations could also benefit from using financial innovations to mitigate the risk of volatile food prices. Forward purchases of supplies can be made when prices dip and before food is needed. These transactions offer flexibility on price, volume, and delivery locations; allow shorter lead times; and provide predictable planning. Call options—the right, but not the obligation, to buy a commodity at a certain price for a period of time—also facilitate access to commodities at lower prices. Because they don’t mandate the purchase, the buyer can back out if the commodity ultimately isn’t needed, forfeiting only the premium paid for the option.

All of these mechanisms have the potential to help humanitarian groups deliver food on time and at low cost to vulnerable populations. The long-term effects of hunger on areas such as health, productivity, and national security make early and efficient crisis responses imperative.

The Success Stories: China and India

As mentioned at the start of the chapter, two developing nations stand out as powerhouses of economic growth. In China and to a lesser extent in India, hundreds of millions of people have shaken off the chains of poverty. Somehow this has been accomplished despite the fact that both countries are regarded as having corrupt legal systems and institutions that would frequently be considered inadequate by Western standards. How have they pulled it off? Innovation has played a key role. Both nations have devised financing and governance methods that fill in gaps left by the standard channels of banks and financial markets.

The Chinese and Indian financial systems are markedly different in their nature and evolution. Transitioning from a socialist system to a market-based system, China had no formal commercial legal framework or associated institutions in place when its economy entered warp speed in the 1980s. India, on the other hand, has a long history of well-developed legal institutions and financial markets.

The Chinese economy can be divided into three categories: 1) the state sector, which includes all companies ultimately controlled by the government (state-owned enterprises, or SOEs); 2) the listed sector, which includes all firms listed on an exchange and publicly traded; and 3) the private sector, which includes all other firms with various types of private and local government ownership.67 The private sector now dominates the state and listed sectors in size, growth, and importance. Although it relies on relatively weaker legal protection and financing channels, the private sector has been racing ahead of the others and has been contributing most of the economy’s growth. This indicates that the private sector has managed to develop effective, alternative financing channels and corporate governance mechanisms, such as those based on reputation and relationships, to support its momentum.

China’s financial system is dominated by a large but underdeveloped banking system that is mainly controlled by the four largest state-owned banks. The Shanghai Stock Exchange and ShenZhen Stock Exchange have been growing by leaps and bounds since their inception in 1990, but their scale and importance are still not comparable to other channels of financing (especially the banking sector) for the Chinese economy as a whole.

The state sector has been shrinking as privatization proceeds apace, with greater numbers of firms going public. Equity ownership is concentrated within the state for firms converted from the state sector, and within founders’ families for nonstate firms. The standard corporate governance mechanisms are weak and ineffective in the listed sector.

By contrast, the private sector is more interesting. The two most important financing channels for these firms during their start-up and subsequent periods are financial intermediaries, including state-owned banks and private credit agencies, and founders’ friends and families. Firms have outstanding loans from multiple financial intermediaries, with most of the loans secured by fixed assets or third-party guarantees. During a firm’s growth period, funds from “ethnic Chinese” investors (from Hong Kong, Taiwan, and other countries) and trade credits from business partners are also important sources.

Though formal governance mechanisms are practically nonexistent, alternative mechanisms have been remarkably effective in the private sector. Reputation and relationships matter above all. The most important force shaping China’s social values and institutions is the widely held set of beliefs related to Confucius; these customs define family and social orders and trust, and are entirely distinct from Western reliance on the rule of law. Another important mechanism that drives good management and corporate governance is simple competition. Given the risks of failure during the early stages of a firm’s development, firms have a strong incentive to gain a comparative advantage. Another important mechanism is the role of local governments. In the Chinese regions that witnessed the most successful economic growth and improvement in living standards, motivated government officials have actively supported the growth of private-sector firms.

India poses a very different set of circumstances. With its English common-law heritage, India offers one of the world’s strongest sets of legal protections for investors.68 Moreover, a British-style judicial system and a democratic government have been in place for a long time. But what exists on the books and what plays out in the day-to-day reality of the business world are two very different things. The effective level of investor protection and the quality of legal institutions in India both remain poor.

The reasons for the wide gap between investor protection on paper and in practice include a slow and inefficient legal system and government corruption. A firm’s equity ownership is typically highly concentrated within the founder’s family and/or the controlling shareholder, more so than in other Asian countries. Surveys indicate that small firms, regardless of age and industry, have little use for the legal system. Most firms prefer not to seek legal recourse in any situation, including customer defaults, breaches of contract, or commercial disputes. On the other hand, nonlegal sanctions in various forms (such as loss of reputation or future business opportunities, or even fear of personal safety) are far more effective deterrents against contract violations and nonpayment than legal recourse, and these strategies are employed widely. India’s case would seem to indicate that strong legal protection is not a necessary condition for conducting business—as long as there are effective, nonlegal “institutional” substitutes.

Formal financing channels based on stock markets and banks are not essential for corporate operations and investments if alternative financing sources pick up the financing slack. In spite of poor investor protection in practice, the Indian economy has outpaced most others since the early 1990s. Further, firm-level evidence indicates that from 1996 to 2005 (a sufficiently long period for which reliable data is available), the average Indian firm grew at an impressive 10.9% compound annual rate. Moreover, in both India and China, SME firms grew even faster, although they depend little on formal legal channels and use far less formal finance than their larger counterparts.

China and India have managed to innovate around the problems that stifle growth in so many emerging economies. Developing alternate channels and mechanisms can speed the way for growth and make it possible to overcome obstacles. The main challenge facing the developing world is how to adapt these strategies to the local culture and surroundings in other nations so that the success of China and India can be emulated in other parts of the world.

Conclusions

Though recent decades have seen dramatic advances in corporate, housing, and environmental finance, this wave of progress has left the field of development finance largely untouched. But finance and information technology can converge again to unleash the potential of entrepreneurial firms in emerging markets, fund the infrastructure improvements that are needed to power growth, and even speed the flow of emergency aid in cases where lives are at stake.

Development finance, a neglected stepchild of Wall Street, Washington, and other global capitals, increasingly finds its place at the table not only for altruistic reasons, but out of self-interest. First and foremost, in this increasingly interconnected global economy, the developing world represents a huge untapped source of future demand and growth. But it’s equally important to realize that development enhances security, for at the heart of most geopolitical conflicts lie persistent problems of inadequate economic growth shared unequally. Regions marked by poverty, blight, and despair are breeding grounds for terrorism and conflict.

Demographic shifts add new urgency to this imperative. While the developed world is graying, many emerging markets are characterized by very young populations. As more young people enter the labor market and seek productive opportunities, job creation, firm formation, and income and wealth generation become imperative. Fostering higher rates of economic growth may always have been the right way to approach development, but over the next half-century, there is really no choice but to finally accomplish it to avoid geopolitical instability.

The examples of China and India show what it is possible. Now the challenge is replicating their success on a worldwide scale.

Endnotes

1 Shaohua Chen and Martin Ravallion, “The Developing World Is Poorer Than We Thought, but No Less Successful in the Fight Against Poverty,” World Bank Development Research Group (August 2008).

2 International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook database.

3 World Bank press release, “World Bank Updates Poverty Estimates for the Developing World” (28 August 2008). Available at http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/NEWS/0,,contentMDK:21882162~menuPK:51062075~pagePK:34370~piPK:34424~theSitePK:4607,00.html.

4 United Nations, press release, “Sub-Saharan Africa’s Progress Towards Anti-Poverty Goals Is Encouraging, But Needs to Be Accelerated to Meet 2015 Targets,” September 12, 2008.

5 Gary S. Becker, Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994).

6 “The Growth Report: Strategies for Sustained Growth and Inclusive Development,” Commission on Growth and Development (2008): 1.

7 OECD, quoted in “Foreign Aid in the National Interest: Promoting Freedom, Security, and Opportunity,” USAID (2002): 133. Available at www.usaid.gov/fani/index.htm.

8 Antoine van Agtmael, The Emerging Markets Century: How a New Breed of World-Class Companies Is Overtaking the World (New York: Free Press, 2007).

9 “Dizzy in Boomtown,” The Economist (15 November 2007).

10 Victoria Papandrea, “Emerging Markets Set to Dominate Global GDP,” Investor Daily (22 October 2009).

11 Shantayanan Devarajan, Margaret J. Miller, and Eric V. Swanson, “Goals for Development: History, Prospects, and Costs,” (working paper no. WPS 2819, World Bank, 2002).

12 United Nations, MDG Gap Task Force Report 2009, “Strengthening the Global Partnership for Development in a Time of Crisis”: ix.

13 Geoff Dyer, “Global Insight: Springing China’s Forex Trap,” Financial Times (19 October 2009).

14 Dambisa Moyo, Dead Aid: Why Aid Is Not Working and How There Is a Better Way for Africa (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2009). See also Chris Lane and Amanda Glassman, “Smooth and Predictable Aid for Health: A Role for Innovative Financing?” (working paper no. 1, Brookings Global Health Financing Initiative, 2008). For an overview of the debate surrounding the effectiveness of the traditional aid model, see Nicholas Kristof, “How Can We Help the World’s Poor?” New York Times (22 November 2009).

15 Steve Beck and Tim Ogden, “Beware of Bad Microcredit,” Harvard Business Review online (September 2007). Available at http://hbr.harvardbusiness.org/2007/09/beware-of-bad-microcredit/ar/1.

16 Robert G. King and Ross Levine, “Finance and Growth: Schumpeter Might Be Right,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 108, no. 3 (1993): 717–737.

17 James R. Barth, D. E. Nolle, Hilton L. Root, and Glenn Yago, “Choosing the Right Financial System for Growth,” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 13, no. 4 (2001): 116–123. See also James R. Barth, Gerard Caprio Jr., and Ross Levine, Rethinking Bank Regulation: Till Angels Govern (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

18 Hernando de Soto, The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Succeeds in the West and Fails Everywhere Else (New York: Basic Books, 2000); and D. C. North, Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

19 Financial Access Initiative, “Half the World Is Unbanked” (October 2009). Available at http://financialaccess.org.

20 United Nations, “The Millennium Development Goals Report 2009”: 51–52.

21 Nancy Gohring, IDG News Service, “Google and Grameen Launch Mobile Services for the Poor,” PC World (29 June 2009).

22 Sara Corbett, “Can the Cellphone Help End Global Poverty?” New York Times (13 April 2008).

23 Sarah McGregor, “Alliance on Banking Services for the Poor Starts First Meeting,” Bloomberg (14 September 2009).

24 Torsten Wezel, “Does Co-Financing by Multilateral Development Banks Increase ‘Risky’ Direct Investment in Emerging Markets?” Discussion Paper Series I: Economic Studies, Deutsche Bundesbank Research Centre (2004).

25 David de Ferranti and Anthony J. Ody, “Beyond Microfinance: Getting Capital to Small and Medium Enterprises to Fuel Faster Development,” Policy Brief no. 159, Brookings Institution (2007).

26 Asli Demirguc-Kunt and Ross Levine, “Finance and Inequality: Theory and Evidence,” Annual Review of Financial Economics 1 (2009): 15.

27 Timothy Besley and Robin Burgess, “Halving Global Poverty,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, American Economic Association 17, no. 3 (2003): 15.

28 Grameen Bank website, “At a Glance,” www.grameen-info.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=26&Itemid=175.

29 Milken Institute Global Conference 2008 panel summary, “Business Innovations That Are Changing the World.” Available at www.milkeninstitute.org/events/gcprogram.taf?function=detail&eventid=GC08&EvID=1395.

30 Elisabeth Rhyne and Maria Otero, “Microfinance Through the Next Decade: Visioning the Who, What, Where, When and How,” Global Microcredit Summit (2006).

31 Estimates from Microfinance Information Exchange and the Microcredit Summit Campaign.

32 Rajdeep Sungupta and Craig P. Aubuchon, “The Microfinance Revolution: An Overview,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 90, no. 1 (January/February 2008): 9–30.

33 “Yunus Blasts Compartamos,” BusinessWeek Online Extra (13 December 2007). Available at www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/07_52/b4064045920958.htm.

34 “The Greatest Entrepreneurs of All Time,” BusinessWeek (27 June 2007).

35 Milken Institute Forum, Creating a World Without Poverty (January 16, 2008). Available at www.milkeninstitute.org/events/events.taf?function=detail&ID=219&cat=Forums.

36 Veolia press release. Available at www.veoliawater.com/press/press-releases/press-2008/20080331,grameen.htm.

37 Clinton Global Initiative press release (23 September 2009).

38 “Adidas to Make 1€ Trainers,” Daily Telegraph (16 November 2009).

39 International Monetary Fund, www.imf.org/external/np/exr/cs/news/2009/021009.htm.

40 Meghana Ayyagari, Thorsten Beck, and Asli Demirguch-Kunt, “Small and Medium Enterprises Across the Globe: A New Database” (working paper no. 3217, World Bank, August 2003).

41 “Finance for All? Policies and Pitfalls in Expanding Access,” World Bank Policy Research Report (2008).

42 Thorsten Beck, Asli Demirguc-Kunt, and Vojislav Maksimovic, “Financial and Legal Constraints to Growth: Does Firm Size Matter?” Journal of Finance (2005): 133–177.

43 This discussion draws on Jill Scherer, Betsy Zeidman, and Glenn Yago, “Structuring Scalable Risk Capital for Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Emerging Markets,” Financial Innovations Lab Report, Milken Institute (August 2009).

44 Acumen Fund, “About Us,” www.acumenfund.org/about-us.html. See also Nicholas Kristof, “How Can We Help the World’s Poor? New York Times (22 November 2009).

45 Root Capital, “What We Do,” www.rootcapital.org/what_we_do.php.

46 “A Place in Society,” The Economist (25 September 2009).

47 Monitor Institute, “Investing for Social & Environmental Impact: A Design for Catalyzing an Emerging Industry” (2009).

48 Antony Bugg-Levine and John Goldstein, “Impact Investing: Harnessing Capital Markets to Solve Problems at Scale,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Community Development Investment Review 5, no. 2 (2009): 30–41.

49 Krishnan Sharma and Manuel Montes, “Strengthening the Business Sector in Developing Countries: The Potential of Diasporas” (United Nations working paper, 2008); Krishnan Sharma, “The Impact of Remittances on Economic Security” (working paper no. 78, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, July 2009).

50 Glenn Yago, Daniela Roveda, and Jonathan White, “Transatlantic Innovations in Affordable Capital for Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises: Prospect for Market-Based Development Finance,” German Marshall Fund/Milken Institute (2007).

51 Small Enterprise Assistance Funds, “From Poverty to Prosperity: Understanding the Impact of Investing in Small and Medium Enterprises” (2007).

52 Commission on Growth and Development, “The Growth Report” (2008): 5.

53 Alan Wheatley, “Asia Could Benefit from Cooperating on Infrastructure,” New York Times (24 November 2009). See also “Study on Intraregional Trade and Investment in South Asia,” Asian Development Bank (2009).

54 Simon Elegant and Austin Ramzy, “China’s New Deal: Modernizing the Middle Kingdom,” Time (1 June 2009)..

55 Steve Hamm and Nandini Lakshman, “The Trouble with India: Crumbling Roads, Jammed Airports, and Power Blackouts Could Hobble Growth,” BusinessWeek (19 March 2007).

56 “Africa’s Infrastructure: A Time for Transformation,” Africa Infrastructure Country Diagnostic (AICD), World Bank (2009).

57 Vivien Foster, William Butterfield, Chuan Chen, and Nataliya Pushak, “Building Bridges: China’s Growing Role as Infrastructure Financier for Sub-Saharan Africa,” World Bank/Public-Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility (July 2008).

58 World Bank press release, “World Bank Group Boosts Support for Developing Countries” (11 November 2008). Available at http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/NEWS/0,,contentMDK:21973077~pagePK:64257043~piPK:437376~theSitePK:4607,00.html.

59 Nachiket Mor and Sanjeev Sehrawat, “Sources of Infrastructure Finance,” Centre for Development Finance, working paper series, Institute for Financial Management and Research, India (October 2006).

60 World Bank press release, “First World Bank Green Bonds Launched” (5 January 2009). Available at http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/NEWS/0,,contentMDK:22024264~pagePK:64257043~piPK:437376~theSitePK:4607,00.html.

61 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, “More People Than Ever Are Victims of Hunger” (June 2009).

62 UNICEF, “Tracking Progress on Child and Maternal Nutrition” (2009).

63 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, “The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2004.”

64 This discussion is drawn from Jill Scherer, Betsy Zeidman, and Glenn Yago, “Feeding the World’s Hungry: Fostering an Efficient and Responsive Food Access Pipeline,” Financial Innovations Lab Report, Milken Institute (October 2009).

65 Owen Barder and Ethan Yeh, “The Costs and Benefits of Front-Loading and Predictability of Immunization,” Center for Global Development (January 2006).

66 Larry Hays, Standard & Poor’s Ratings Direct report, “International Finance Facility for Immunisation” (9 July 2009).

67 See Franklin Allen, Jun Qian, and Meijun Qian, “Law, Finance, and Economic Growth in China,” Journal of Financial Economics 77, (2003): 57–116; and Franklin Allen, Jun Qian, Meijun Qian, and Mengxin Zhao, “A Review of China’s Financial System and Initiatives for the Future,” in James R. Barth, John A. Tatom, and Glenn Yago (eds.), China’s Emerging Financial Markets: Challenges and Opportunities (New York: Springer, 2009).

68 Franklin Allen, Rajesh Chakrabarti, Sankar De, Jun Qian, and Meijun Qian, “Financing Firms in India” (working paper, Wharton Financial Institutions Center, 2008).