14

Sequences and magazines

Of all programme types, it is the regular sequences and magazines that can so easily become boring or trivial by degenerating into a ragbag of items loosely strung together. To define the terms, a sequence or strip programme is the lengthy slot – generally between two and four hours – often daily, such as the morning show or drive-time, etc., using music with a wide audience appeal, and with an emphasis on the presentation. Whereas a magazine is usually designed with a specific audience in mind and tightly structured, with the emphasis on content. For both, the major problem for the producer is how best to balance the need for consistency with that of variety. Clearly there has to be a recognizable structure to the programme – after all, this is probably why the listener switched on in the first place – but there must also be fresh ideas and newness.

An obvious policy of marketing, which applies to radio no less than to any other product, is to build a regular audience by creating positive listener expectations and then to fulfil or, better still, exceed them. The most potent reason for tuning in to a particular programme is that the listener liked it the last time. This time, therefore, the programme must be of a similar mould, not too much must be changed. It is equally obvious, however, that the programme must be new in the sense that it must have fresh and updated content and contain the element of surprise. The programme becomes boring when its content is too predictable, yet it fails if its structure is obscure. It is not enough simply to offer the advice ‘keep the format consistent but vary the content’. Certainly, this is important, but there must be consistencies too in the intellectual level and emotional appeal of the material. From edition to edition there must be the same overall sense of style.

Since we have so far borrowed a number of terms from the world of print, it might be useful to draw the analogy more closely.

The newspapers and magazines we buy are largely determined by how we reacted to the previous issue. To a large extent purchases are a matter of habit and although some are bought on impulse, or by accident, changes in readership occur relatively slowly. Having adopted our favourite periodical, we do not care to have it tampered with in an unconsidered way. We develop a personal interest in the typography, page layout, length of feature article or use of pictures. We know exactly where to find the sports page, crossword or favourite cartoon. We take a paper which appeals to us as individuals; there is an emotional link and we can feel distinctly annoyed should a new editor change the typeface, or start moving things around when, from the fact that we bought it, it was all right as it was. In other words, the consistency of a perceived structure is important since it leads to a reassurance of being able to find your way around, of being able to use the medium fully. Add a familiar style of language, words that are neither too difficult nor too puerile, sentences which avoid both the pompous and the servile, captions which illuminate and not duplicate, and it is possible to create a trusting bond between the communicator and the reader, or in our case the listener. Different magazines will each decide their own style and market. It is possible for a single publisher, as it is for the manager of a radio station, to create an output with a total range aimed at the aggregate market of the individual products.

For the individual producer, the first crucial decision is to set the emotional and intellectual ‘width’ of a programme and to recognize when there is a danger of straying outside it.

To maintain programme consistency several factors must remain constant. A number of these are now considered.

Programme title

This is the obvious signpost and it should both trigger memories of the previous edition and provide a clue to content for the uninitiated. Titles such as ‘Farm’, ‘Today’, ‘Sports Weekly’ and ‘Woman's Hour’ are self-explanatory. ‘Roundabout’, ‘Kaleidoscope’, ‘Miscellany’ and ‘Scrapbook’ are less helpful except that they do indicate a programme containing a number of different but not necessarily related items. With a title like ‘Contact’ or ‘Horizon’, there is little information on content, and a subtitle is often used to describe the subject area. Sequences, like DJ programmes, are often known by the name of the presenter – ‘The Jack Richards Show’ – but a magazine title should stem directly from the programme aims and the extent to which the target audience is limited to a specialist group.

Signature tune

The long sequence is designed to be listened to over any part at random – to dip in and out of. A signature tune is largely irrelevant, except to distinguish it from the previous programme, serving as an additional signpost intended to make the listener turn up the volume. It should also convey something of the style of the programme – light-hearted, urgent, serious or in some way evocative of the content. Fifteen seconds of the right music can be a useful way of quickly establishing the mood. Magazine producers, however, should avoid the musical cliché. While ‘Nature Notebook’ may require a pastoral introduction, the religious magazine will often make strenuous efforts not to use opening music that is too churchy. If the aim is to attract an audience that already identifies with institutionalized religion, some kind of church music may be fine. If, on the other hand, the idea is to reach an audience that is wider than the churchgoing or sympathetic group, it may be better to avoid too strong a church connotation at the outset. After all, the religious magazine is by no means the same as the Christian magazine or the church programme.

Transmission time

Many stations construct their daily schedule with a series of sequences in fixed blocks of three or four hours. It is obviously important to have the right presenter and the right style of material for each time slot. The same principle holds for the more specialist magazine. Regular programmes must be at regular times and regular items within programmes given the same predictable placing in each programme. This rule has to be applied even more rigorously as the specialization of the programme increases.

For example, a half-hour farming magazine may contain a regular three-minute item on local market prices. The listener who is committed to this item will tune in especially to hear it, perhaps without bothering with the rest of the programme. A sequence having a wider brief, designed to appeal to the more general audience, is more likely to be on in the background and it is therefore possible to announce changes in timing. Even so, the listener at home in the mid-morning wants the serial instalment, item on current affairs or recipe spot at the same time as yesterday, since it helps to orientate the day.

The presenter

Perhaps the most important single factor in creating a consistent style, the presenter regulates the tone of the programme by his or her individual approach to the listener. This can be outgoing and friendly, quietly companionable, informal or briskly businesslike, or knowledgeable and authoritative. It is a consistent combination of characteristics, perhaps with two presenters, which allows the listener to build a relationship with the programme based on ‘liking’ and ‘trusting’. Networks and stations which frequently change their presenters, or programmes that ‘rotate’ their anchor people, are simply not giving themselves a chance. Occasionally you hear the justification of such practice as the need ‘to prevent people from becoming stale’ or, worse, ‘to be fair to everyone working on the programme’. Most programme directors would recommend a six-month period as the minimum for a presenter on a weekly programme and three months for a daily show. Less than this and they may hardly have registered with the listener at all.

In selecting a presenter for a specialist magazine, the producer may be faced with a choice of either a good broadcaster or an expert in the subject. Obviously the ideal is to find both in the same person, or through training to turn one into the other – the easier course is often to enable the latter to become the former. If this is not possible, an alternative is to use both. Given a strict choice, the person who knows the material is generally preferable. Credibility is a key factor in whether or not a specialist programme is listened to, and expert knowledge is the foundation, even though it may not be perfectly expressed. In other words, if we have a doctor for the medical programme and a gardener for the gardening programme, should there be children for the children's show, and a disabled person introducing a programme for the handicapped? In a magazine programme for the blind there may be a bit more paper shuffling ‘off-mic’, and the Braille reading may not be as fluent as with a sighted reader, but the result is likely to have much more impact and be far more acceptable to the target audience.

Linking style

Having established the presenter, or presenters, and assuming he or she will write, or at least rewrite, much of the script, the linking material will have its own consistent style. The way in which items are introduced, the amount and type of humour used, the number of time checks, and the level at which the whole programme is pitched will remain constant. Although sounding as though it is spontaneous, off-the-cuff comment, what is said needs to be worked on in advance in order to contain any substance. The links enable the presenter to give additional information, personalized comment or humour. The ‘link-person’ is much more than a reader of item cues, and it is through the handling of the links more than anything else that the programme develops a cohesive sense of style.

Information content

The more local a sequence becomes, the more specific and practical can be the information it gives. It may be either carried in the form of regular spots at known times or simply included in the links. If a programme sets out with the intention of becoming known for its information content, the spots must be distinctive, yet standardized in terms of timing, duration, style, ‘signposting’, introductory ident or sound effect.

The types of useful information will naturally depend on the particular needs of the audience in the area covered by the station. The list is wide ranging and typical examples for inclusion in a daily programme are:

Programme construction

The overall shape of the programme will remain reasonably constant. The proportion of music to speech should stay roughly the same between editions, and if the content normally comprises items of from three to five minutes’ duration ending with a featurette of eight minutes, this structure should become the established pattern. This is not to say that a half-hour magazine could not spend 15 minutes on a single item given sufficient explanation by the presenter. But it is worth pointing out that by giving the whole or most of a programme over to one subject, it ceases to be a magazine and instead becomes a documentary or feature. There is an argument to be made in the case of a specialist programme for occasionally suspending the magazine format and running a one-off ‘special’ instead, in which case this should of course be aimed at the same audience as the magazine it replaces. Another permissible variation in structure is where every item has a similar ‘flavour’ – as in a ‘Christmas edition’, or where a farming magazine is done entirely at an agricultural show.

Such exceptions are only possible where a standard practice has become established, for it is only by having ‘norms’ that one is able to introduce the variety of departing from them.

Sequences are best designed in the clock format described in the previous chapter.

Programme variety

Each programme should create fresh interest and contain surprise. First, the subject matter of the individual items should itself be relevant and new to the listener. Second, the treatment and order of the items need to highlight the differences between them and maintain a lively approach to the listener's ear. It is easy for a daily magazine, particularly the news magazine, to become nothing more than a succession of interviews. Each may be good enough in its own right, but heard in the context of other similar material, the total effect may be worthy but dull. In any case, long stretches of speech, especially by one voice, should be avoided. Different voices, locations, actuality, and the use of music bridges and stings can produce an overall effect of brightness and variety – not necessarily superficial, but something people actually look forward to.

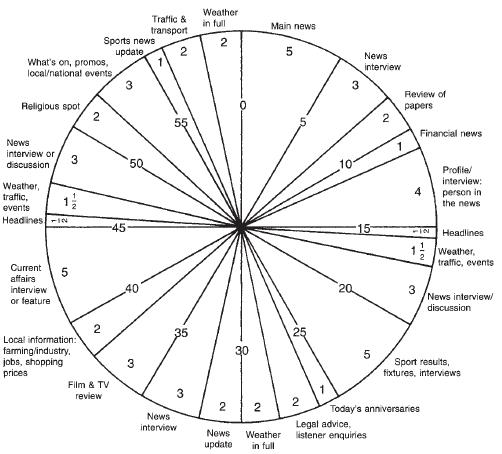

Figure 14.1 The clock format applied to an all-speech, news-based, non-commercial, breakfast sequence. Typically programmed from 6.30 to 9.00 a.m., it requires a range of news, weather, sport and information sources, plus five interviews in the hour – live, telephoned or recorded. With repeats this might total nine in the two and a half hours. Interviewees will be drawn mainly from politicians, people in the news, officials, ‘experts’ and media observers. Large organizations will have their own correspondents and local stringers. Presentation will include station idents, time, temperature, promos and incidental information

Programme ideas

Producing a good programme is one thing, sustaining it day after day or week after week, perhaps for years, is quite another. How can anyone, with little if any staff assistance, set about the task of finding the items necessary to keep the programme going? First, a producer is never off duty but is always wondering if anything noticed, seen or heard will make an item. Record even the passing thought or brief impression, probably in a small notebook that is always carried. It is surprising how the act of writing down even a flimsy idea can help it to crystallize into something more substantial. Second, through a diary and other sources, note advance information on anniversaries and other future events. Third, cultivate a wide range of contacts. This means reading, or at least scanning, as much as possible: newspapers, children's comics, trade journals, parish magazines, the small ads, poster hoardings, the internet – anything which experience has shown can be a source of ideas.

Producers need to get out of the studio and walk through the territory – easier in local radio than for a national broadcaster! Be a good listener, both to the media and in personal conversation. Be aware of people's problems and concerns, and of what makes them laugh. Encourage contributors to come up with ideas and, if there is no money to pay them, at least make sure they get the credit for something good. If you are too authoritarian or adopt a ‘know it all’ attitude, people will leave you alone. But by being available and open, people will come to you with ideas. Welcome correspondence. It is hard work but the magazine/sequence producer soon develops a flair for knowing which of a number of slender leads is likely to develop into something for the programme.

Having decided to include an item on a particular subject, the producer has several options on the treatment to employ. A little imagination will prevent a programme from sounding ‘samey’ – consider how to increase the variety of a programme by using the following radio forms.

Voice piece

A single voice giving information, as with a news bulletin, situation report or events diary. This form can also be used to provide eyewitness commentary, or tell a story of the ‘I Was There’ type of personal reminiscence.

A voice piece lacks the natural variety of the interview and must therefore have its own colour and vitality. In style, it should be addressed directly to the listener – pictorial writing in the first person and colloquial delivery, as discussed in Chapter 4, can make compelling listening. But more than this, there must also be a reason for broadcasting such an item. There needs to be some special relevance – a news ‘peg’ on which to hang the story. The most obvious one lies in its immediacy to current events. Topicality, trends or ideas relevant to a particular interest group, innovation and novelty, or a further item in a useful or enjoyable series, are all factors to be used in promoting the value of items in a magazine.

Interview

The types of interview (see Chapter 6) include those which challenge reasons, discover facts or explore emotions. This sub-heading also includes the vox pop or ‘man in the street’ opinion interview. A further variation is the question and answer type of conversation done with another broadcaster – sometimes referred to as ‘Q & A’ or a two-way. Using a specialist correspondent in this way, the result is often less formal, though still authoritative.

Discussion

Exploration of a topic in this form within a magazine programme will generally be of the bidirectional type, consisting of two people with opposing, or at least non-coincident, views. To attempt in a relatively brief item to present a range of views, as in the ‘multi-facet’ discussion, will often lead to a superficial and unsatisfactory result. If a subject is big enough or important enough to be dealt with in this way, the producer should ask whether it shouldn't have a special programme.

Music

An important ingredient in achieving variety, music can be used in a number of ways:

1 As the major component in a sequence.

2 An item, concert performance or recording featured in its own right.

3 A new item reviewed.

4 Music which follows naturally upon the previous item. For example, an interview with a choir about to make a concert debut followed by an illustration of their work.

5 Where there is a complete change of subject, music can act as a link – a brief music ‘bridge’ may be permissible. This is particularly useful to give ‘thinking time’ after a thoughtful or emotional item where a change of mood is required.

Music should be used as a positive asset to the programme and not merely to fill time between items. It can be used to supply humour or provide wry comment on the previous item, e.g. a song from My Fair Lady could be a legitimate illustration after a discussion about speech training. Its use, however, should not be contrived merely because its title has a superficial relevance to the item. It would be wrong, for example, to follow a piece about an expedition to the Himalayas with ‘Climb Every Mountain’ from the Sound of Music. For someone who looks no further than the track notes there appears to be a connection, but the discontinuity of context can lead to accusations of poor judgement.

One of the most difficult production points in the use of the medium is the successful combination of speech and music. Music is much more divisive of the audience, since listeners generally have positive musical likes and dislikes. It is also very easy to create the wrong associations, especially among older people, and real care has to be taken over its selection.

Sound effects

Like music, effects or actuality noises can add enormously to what might otherwise be a succession of speech items. They stir the memory and paint pictures. An interview on the restoration of an old car would surely be accompanied by the sound of its engine and an item on dental techniques by the whistle of a high-speed drill. The scene for a discussion on education could be set by some actuality of playground or classroom activity, and a voice piece on road accident figures would catch the attention with the squeal of brakes. These things take time and effort to prepare and, if overdone, the programme suffers as it will from any other cliché. But used occasionally, appropriately and with imagination, the programme will be lifted from the mundane to the memorable. You do not have to be a drama producer to remember that one of the strengths of the medium is the vividness of impression that can be conveyed by simple sounds.

Listener participation

Daily sequences in particular like to stimulate a degree of audience involvement and the producer has several ways of achieving this, as discussed in Chapter 12.

Regarding a spot for letters and e-mails, it is important that programme presenters do not read letters or reply to them in a patronizing way, but respond to them as to a valued friend. Broadcasters are neither omniscient nor infallible, and should always distinguish between a factual answer, best advice and a personal opinion. Some basic and essential reference sources – books, databases, available experts, etc. – will provide answers for questions like, why does the leaning tower of Pisa lean? Or, how do you remove bloodstains from cloth? But it is a quite different matter replying to questions about how to invest your money, a cure for cataracts, the causes of a rising crime rate or why a loving God allows suffering. Nevertheless, without being glib or superficial, it is possible for such a letter to spark off an interesting and useful discussion, or for the presenter to give an informed and thought-out response with:

‘On balance I would say that …’ or

‘If you are asking for my own opinion I'd say … but let me know what you think.’

Research may have thrown up a suitable quote or piece of writing on the subject, which should of course always be attributed. Other phrases useful here are:

‘Experts seem to agree that …’

‘No one really knows, but …’

Competitions are a good method of soliciting response. These could be in reply to quizzes and on-air games with prizes offered, or simply for the fun of it.

A phone-in spot in a live magazine helps the sense of immediacy and can provide feedback on a particular item. Placed at the end, it can allow listeners the opportunity of saying what they thought of the programme as a whole. Used in conjunction with a quiz competition, it obviously allows for answers to be given and a result declared within the programme.

Listener participation elements need proper planning, but part of their attraction lies in their live unpredictability. The confident producer or presenter will know when to stay with an unpremeditated turn of events and extend an item which is developing unexpectedly well. He or she will have also determined beforehand the most likely way of altering the running order to bring the programme back on schedule. In other words, in live broadcasting the unexpected always needs to be considered.

Features

A magazine will frequently include a place for a package of material dealing with a subject in greater depth than might be possible in a single interview. Often referred to as a featurette, the general form is either person centred (‘our guest this week is …’ ), place centred (‘this week we visit …’ ) or topic centred (‘this week our subject is …’ ).

Even the topical news magazine, in which variety of item treatment is particularly difficult to apply, will be able to consider putting together a featurette comprising interview, voice piece, archive material, actuality and links, even possibly music. For instance, a report on the scrapping of an old ferry boat could be run together with the reminiscences of its former skipper, describing some perilous exploit, with the appropriate sound effects in the background. Crossfade to breaker's yard and the sound of lapping water. This would be far more interesting than a straight report.

The featurette is a good means of distilling a complex subject and presenting its essential components. The honest reporter will take the crux of an argument, possibly from different recorded interviews, and present them in the context of a linked package. They should then form a logical, accurate and understandable picture on which the listener can base an opinion.

Drama

The weekly or daily serial or book reading has an established place in many programmes. It displays several characteristics that the producer is attempting to embody – the same placing and introductory music, a consistent structure, familiar characters, and a single sense of style. On the other hand, it needs a variety of new events, some fresh situations and people, and the occasional surprise. But drama can also be used in the one-off situation to make a specific point – for example, in describing how a shopper should compare two supermarket products in order to arrive at a best buy. It can be far more effective than a talk by an official, however expert. Lively, colloquial, simple dialogue, using two or three voices with effects behind it to give it location – in a store or factory, on a bus or at the hospital – this can be an excellent device for explaining legislation affecting citizens’ rights, a new medical technique, or for providing background on current affairs. Scriptwriters, however, will recognize in the listener an immediate rejection of any expository material which has about it the feel of propaganda. The most useful ingredients would appear to be: ordinary everyday humour, credible characters with whom the listener can identify, profound scepticism and demonstrable truth.

Programmes for children use drama to tell stories or explain a point in the educational sense. The use of this form may involve separate production effort, but it can be none the less effective by being limited to the dramatized reading of a book, poem or historical document.

Item order

Having established the programme structure, set the overall style and decided on the treatment of each individual item, the actual order of the items can detract from or enhance the final result.

In the case of a traditional circus or variety performance in a theatre, the best item – the top of the bill – is kept until last. It is safe to use this method of maintaining interest through the show since the audience is largely captive and it underwrites the belief that, whatever the audience reaction, things can only get better. With radio, the audience is anything but captive and needs a strong item at the beginning to attract the listener to the start of the show, thereafter using a number of devices to hold interest through to the end. These are often referred to as ‘hooks’ – remarks or items designed to capture and retain the listener's attention. It is crucial to engage the audience early in the programme – an enticing, imaginatively written menu is one way of doing this – but then to continue to reach out, to appeal to the listener's sense of fun, curiosity or need. Of course, this applies to all programmes, but the longer strip programming is particularly susceptible to becoming bland and characterless. There should always be something coming up to look forward to.

The news magazine will probably start with its lead story and gradually work through to the less important. However, if this structure is rigidly applied the programme becomes less and less interesting – what has been called a ‘tadpole’ shape. News programmes are therefore likely to keep items of known interest until the end, e.g. sport, stock markets and weather, or at least end with a summary for listeners who missed the opening headlines. Throughout the programme, as much use as possible will be made of phrases like ‘more about that later’. Some broadcasters deliberately avoid putting items in descending order of importance in order to keep ‘good stuff for the second half’ – a dubious practice if the listener is to accept that the station's editorial judgement is in itself something worth having. A better approach is to follow a news bulletin with an expansion of the main stories in current affairs form.

The news magazine item order will be dictated very largely by the editor's judgement of the importance of the material, while in the tightly structured general magazine the format itself may leave little room for manoeuvre. In the more open sequence other considerations apply and it is worth noting once again the practice of the variety music bill. If there are two comedians they appear in separate halves of the show, something breathtakingly exciting is followed by something beautiful and charming, the uproariously funny is complemented by the serious or sad, the small by the visually spectacular. In other words, items are not allowed simply to stand on their own, but through the contrast of their own juxtaposition and the skill of the compère they enhance each other so that the total effect is greater than the sum of the individual parts.

So it should be with the radio magazine. Two interviews involving men's voices are best separated. An urgently important item can be heightened by something of a lighter nature. A long item needs to be followed by a short one. Women's voices, contributions by children or old people should be consciously used to provide contrast and variety. Tense, heated or other deeply felt situations need special care, for to follow with something too light or relaxed can give rise to accusations of trivialization or superficiality. This is where the skill of the presenter counts, for it is his or her choice of words and tone of voice that must adequately cope with the change of emotional level.

Variations in item style combined with a range of item treatment create endless possibilities for the imaginative producer. A programme which is becoming dull can be given a ‘lift’ with a piece of music halfway through, some humour in the links, or an audience participation spot towards the end. For a magazine in danger of ‘seizing up’ because the items are too long, the effect of a brief snippet of information in another voice is almost magical. And all the time the presenter keeps us informed on what is happening in the programme, what we are listening to and where we are going to next, and later. The successful magazine will run for years on the right mixture of consistency of style and unpredictability of content. It could be that, apart from its presenter, the only consistent characteristic is its unpredictability.

The following examples of the magazine format are not given as ideals, but as working illustrations of the production principle. Commercial advertising has been omitted in order to show the programme structure more clearly, but the commercial station can use its breaks to advantage, providing an even greater variety of content.

Example 1: Fortnightly half-hour industrial magazine |

||

Structure |

Running order |

Actual timing |

Standard opening (1′15″) |

Signature tune |

0 15 |

Follow-up to previous programmes |

35 |

|

News (5 min) |

News round-up |

5 05 |

Link |

15 |

|

Item |

Interview on lead news story |

3 08 |

Link – information |

30 |

|

Item |

Voice piece on new process |

1 52 |

Link |

15 |

|

Item |

Vox pop – workers’ views of safety rules |

1 15 |

Link |

20 |

|

Trades Council spot (2½ min) |

Union affairs – spokesman |

2 20 |

Link |

20 |

|

Participation |

Listeners’ letters |

2 45 |

spot (3 min) |

Link – introduction |

20 |

Discussion |

Three speakers join presenter for discussion of current issue – variable length item to allow programme to run to time | 6 20 |

Financial news (3 min) |

Market trends |

3 00 |

Standard closing (50″) |

Coming events |

30 |

Expectations for next programme |

10 |

|

Signature tune |

10 |

|

29′50″ |

||

In Example 1, the programme structure allows 1′ 15″ for the opening and 50″ for the closing. Other fixed items are a total of 8′00″ for news, 3′ 00″ for letters and 2′ 30″ for the Union spot. About 2′ 00″ are taken for the links. This means that just over half the programme runs to a set format, leaving about 13′ 00″ for the two or three topical items at the front and the discussion towards the end.

So long as the subject is well chosen the discussion is useful for maintaining interest through the early part of the programme since it preserves at least the possibility of controversy, interest and surprise. With a ‘live’ broadcast it is used as the buffer to keep things on time since the presenter can then bring it to an end and get into the ‘Market trends’ four minutes before the end of the programme. The signature tune is ‘prefaded to time’ to make the timing exact. With a recorded programme the discussion is easily dropped in favour of a featurette, which in this case might be a factory visit.

| Example 2: Weekly 25-minute religious current affairs | ||

| Structure | Running order | Timing |

| Standard opening (15″) | Introduction | 0 05 |

| Menu of content | 0 10 | |

| Item | Interview – main topical interest | 3 20 |

| Link | 30 | |

| Item | Interview – woman missionary | 2 05 |

| Link | 10 | |

| Music (3min) | Review of gospel record release | 2 40 |

| Link – information | 55 | |

| Item | Interview (or voice piece) – forthcoming convention | 2 30 |

| Link | 05 | |

| Featurette (7min) | Personality – faith and work | 7 10 |

| Link | 15 | |

| News (5min) | News round-up and What's On events | 4 45 |

| Standard closing (15″) | Closing credits | 15 |

| 24′55″ | ||

In Example 2, with no signature tune, the presenter quickly gets to the main item. Although in this edition all the items are interviews, they are kept different in character and music is deliberately introduced at the midpoint. The opening and closing take half a minute and the other fixed spots are allocated another 15 minutes. If the programme is too long, adjustment can be made either by dropping some stories from the news or by shortening the music review. If it under-runs, a repeat of some of the record release can make a useful reprise at the end.

In Example 3, the speech/music ratio is regulated to about 3:1. A general pattern has been adopted that items become longer as the programme proceeds. Each half of the programme contains a ‘live’ item which can be ‘backtimed’ to ensure the timekeeping of the fixed spots. These are respectively the studio discussion and the special guest interview. Nevertheless, the fixed spots are preceded by non-vocal music prefaded to time for absolute accuracy. Fifteen minutes is allowed for links. An alternative method of planning this running order is by the clock format illustrated on p. 176.

Production method

A regular magazine or sequence has to be organized on two distinct levels – the long term and the immediate. Long-term planning allows for anniversaries, ‘one-off editions’, the booking of guests reflecting special events, or the running of related spots to form a series across several programmes. On the immediate time-scale, detailed arrangements have to be finalized for the next programmes.

In the case of the fortnightly or weekly specialist magazine of the type represented in Examples 1 and 2, it is a fairly straightforward task for the producer to make all the necessary arrangements in association with the presenter and a small group of contributors acting as reporters or interviewers. The newsroom or sources of specialist information will also be asked for a specific commitment. The important thing is that everyone has a precise brief and deadline. It is essential too that, while the producer will make the final editorial decisions, all the contributors feel able to suggest ideas. Good ideas are invariably ‘honed up’, polished and made better by the process of discussion. Suggestions are progressed further and more quickly when there is more than one mind at work on them. Almost all ideas benefit from the process of counter-suggestion, development and resolution. Lengthy programmes of this nature are best produced by team-working with clear leadership. This should be the pattern encouraged by the producer at the weekly planning meeting, by the end of which everyone should know what they have to do by when, and with what resources.

The daily sequence illustrated by Example 3 is more complex and such a broadcast will require a larger production team. Typically, the main items such as the serial story and special guest in the second half will have been decided well in advance, but the subject of the discussion in the first may well be left until a day or two beforehand in order to reflect a topical issue. A retrospective look at something recently covered, the further implications of yesterday's story, a ‘whatever happened to … ?’ spot – these are all part of the daily programme. Responsibility for collating the listeners’ letters, organizing the quiz and producing the ‘Out and about’ item will be delegated to specific individuals, and the newsroom will be made responsible for the current affairs voice piece, the news, sport and weather package, and perhaps one of the other interviews. The presenter will write the links and probably select the music, according to station policy. The detail is regulated at a morning planning meeting, the final running order being decided against the format structure that serves as the guideline.

At less frequent intervals, say once a month, the opportunity should be taken to stand back to review the programme and take stock of the longterm options. In this way, it may be possible to prevent the onset of the more prevalent disease of the regular programme – getting into a rut – while at the same time avoiding the disruptive restlessness which results from an obsession with change. When you have become so confident about the success of the programme that you fail to innovate, you have already started the process of staleness that leads to failure. A good approach is constantly to know what you are up against. Identify your competition and ask ‘What must I do to make my programme more distinguishable from the rest?’

Responding to emergency

Sooner or later all the careful planning has to be discarded in order to cope with emergency conditions in the audience area. Floods, snowfall, hurricane, earthquake, power failure, bush fire or major accident will cause a sequence to cancel everything except the primary reason for its existence – public service. It will provide information to isolated villages, link helpers with those in need, and act as a focus of community activity. ‘Put something yellow in your window if you need a neighbour to call.’ ‘Here's how to attract the attention of the rescue helicopter which will be in your area at 10 o'clock ….’ ‘The following schools are closed ….’ ‘The army is opening an emergency fuel depot at ….’ ‘A spare generator is available from ….’ ‘Can anyone help an elderly woman at … ?’ The practical work that radio does in these circumstances is immense, its morale value in keeping isolated, and sometimes frightened, people informed is incalculable. Broadcasters are glad to work for long hours when they know that their service is uniquely valued.

The flexibility offered by the sequence format enables a station to cover a story, draw attention to a predicament, or devote itself totally to audience needs as the situation demands. Radio services should have their contingency plans continuously updated – at least reviewed annually – in order to be able to respond quickly to any situation. Programmers cannot afford to wait for an emergency before making decisions, but must always be asking the question ‘what if … ?’