17

Commentary

Radio has a marvellous facility for creating pictures in the listener's mind. It is more flexible than television in that it is possible to isolate a tiny detail without waiting for the camera to ‘zoom in’ and it can create a breadth of vision much larger than the dimensions of a glass screen. The listener does more than simply eavesdrop on an event; radio, more easily than television or video, can convey the impression of actual participation. The aim of the radio commentator is therefore to recreate in the listener's mind not simply a picture but a total impression of the occasion. This is done in three distinct ways:

1 The words used will be visually descriptive of the scene.

2 The speed and style of their delivery will underline the emotional mood of the event.

3 Additional ‘effects’ microphones will reinforce the sounds of the action, or the public reaction to it.

Attitude to the listener

In describing a scene the commentator should have in mind ‘a blind friend who couldn't be there’. It is important to remember the obvious fact that the listener cannot see. Without this, it is easy to slip into the situation of simply chatting about the event to ‘someone beside you’. The listener should be regarded as a friend because this implies a real concern to communicate accurately and fully. The commentator must use more than his or her eyes and convey information through all the senses, so as to heighten the feeling of participation by the listener. Thus, for example, temperature, the proximity of people and things, or the sense of smell are important factors in the overall impression. Smell is particularly evocative – the scent of newly mown grass, smoke from a fire, the aroma inside a fruit market or the timeless mustiness of an old building. Combine this with the appropriate style of delivery, and the sounds of the place itself, and you are on the way to creating a powerful set of pictures.

Preparation

Some of the essential stages are described in Chapter 16, but the value of a pre-transmission site visit cannot be overemphasized. Not only must the commentator be certain of the field of vision and whether the sun is likely to be in your eyes, but it is important to spend time obtaining essential facts about the event itself. For example, in preparing for a ceremonial occasion, research:

1 The official programme of events with details of timing, etc.

2 The background of the people taking part, their titles, medals and decorations, position, relevant history, military uniforms, regalia or other clothing, personal anecdotes – for the unseen as well as the seen, e.g. organizers, bandmasters, security people, caretakers, etc.

3 The history of where it's taking place, the buildings and streets, and their architectural detail.

4 The names of the flowers used for decoration, the trees, flags, badges, mottoes and symbols in the area. The names of any horses or make of vehicles being used.

5 The titles of music to be played or sung, and any special association it may have with the people and the place.

It adds immeasurably to the description of a scene to be able to mention the type of stonework used in a building, or that ‘around the platform are purple fuchsias and hydrangeas’. The point of such detail is to use it as contrast with the really significant elements of the event, so letting them gain in importance. Contrast makes for variety and for more interesting listening, and mention of matters both great and small is essential, particularly for an extended piece. An eye for detail can also be the saving of a broadcast when there are unexpected moments to fill. There is no substitute for a commentator doing proper homework.

In addition to personal observation and enquiry, useful sources of information will be the Internet, reference sections of libraries or museums, newspaper cuttings, back copies of the event programme, previous participants, specialist magazines, and commercial or government press offices.

Having obtained all the factual information in advance, the commentator must assemble it in a form that can be used in the conditions prevailing at the OB. If perched precariously on top of a radio car in the rain, clutching a guardrail and holding a microphone, stopwatch and an umbrella, the last thing you want is a bundle of easily windblown papers! Notes should be laid out on as few sheets as possible and held firmly on a clipboard. Cards may be useful since they are silent to handle. The important thing is their order and logic. The information will often be chronological in nature, listing the background of the people taking part. This is particularly so where the participants appear in a predetermined sequence – a procession or parade, variety show, race meeting, athletics event, church service or civic ceremony. Further information on the event or the environment can be on separate pages so long as they can be referred to easily. If the event is non-sequential – for instance, a football match or public meeting – the personal information may be more useful in alphabetical form, or better still memorized.

Working with the base studio

The commentator will need to know the precise handover details. This applies both from the studio to the commentator and at the end for the return to the studio. These details are best written down, for they easily slip the memory. There should also be clarity at both ends about the procedures to be followed in the event of any kind of circuit failure – the back-up music to be played and who makes the decision to restore the programme. It may be necessary to devise some system of hand signals or other means of communication with technical staff, and on a large OB whether all commentators will get combined or individual ‘talkback’ on their headphones, etc. These matters are the ‘safety nets’ which enable the commentators to fulfil their role with a proper degree of confidence.

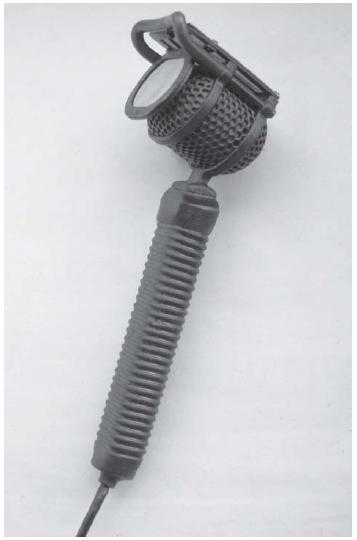

Figure 17.1 The lip mic. The microphone has excellent noise-cancellation properties, which makes it ideal for commentary situations. The mouthguard is held against the broadcaster's lip while the microphone is in use. There is a bass cut in the handle to compensate for the bass lift that results from working close to a ribbon microphone

As with all outside broadcasts, the base studio should ensure that the commentary output is recorded. Not only will the commentator be professionally curious as to how it came over, but the material may be required for archive purposes. Even more important is that an event worthy of a ‘live’ OB will almost certainly merit a broadcast of edited highlights later in the day.

Sport

First and foremost, the sports commentator must know his or her sport and have detailed knowledge of the particular event. What was the sequence that led up to this event? What is its significance in the overall contest? Who are the participants and what is their history? The possession of this background information is elementary, but what is not so obvious is how to use it. The tendency is to give it all out at the beginning in the form of an encyclopedic but fairly indigestible introduction. Certainly, the basic facts must be provided at the outset, but a much better way of using background detail is as the game, race or tournament itself proceeds, at an appropriate moment or during a pause in the action. This way, the commentator sounds much more as part of what is going on instead of being a rather superior observer.

Traditionally, for technical reasons, the commentator has often had to operate from inside a soundproof commentary position, isolated from the immediate surroundings. It's easy to lose something of the atmosphere by creating too perfect an environment, and there is a strong argument in favour of the ringside seat approach, provided that it is possible to use a noise-cancelling microphone and that communication facilities, such as headphone talkback, are secure.

Sports stadia seem to undergo more frequent changes to their layout than other buildings and unless a particular site is in almost weekly use for radio work, a special reconnaissance visit is strongly advised. It is easy to forego the site reconnaissance assuming that the place will be the same as it was six months ago. However, unless there are strong reasons to the contrary, a visit and technical test should always be made.

Where the action is spread out over a large area, as with horse racing, golf, motor racing, a full-scale athletics competition or rowing event, more than one commentator is likely to be in action. Cueing, handovers, timing, liaison with official results – all these must be precisely arranged. The more complex an occasion, the more necessary is observance of the three golden rules for all broadcasts of this type:

1 Meticulous production planning so that everyone knows what they are likely to have to do.

2 First-class communications for control.

3 Only one person in charge.

Communicating mood

The key question is ‘what is the overall impression here?’ Is it one of joyful festivity or is there a more intense excitement? Is there an urgency to the occasion or is it relaxed? At the other end of the emotional scale there may be a sense of awe, a tragedy or a sadness that needs to be reflected in a sombre dignity. Look at people's faces – they will tell you. Whatever is happening, the commentator's sensitivity to its mood, and to that of the spectators, will control matters of style, use of words and speed of delivery. More than anything else this will carry the impressions of the event in the opening moments of the broadcast. The mood of the crowd should be closely observed – anticipatory, excited, happy, generous, relaxed, impressed, restive, sullen, tense, angry, solemn, sad. Such feelings should be conveyed in the voice of the commentator and their accurate assessment will indicate when to stop and let the sounds of the event speak for themselves.

Coordinating the images

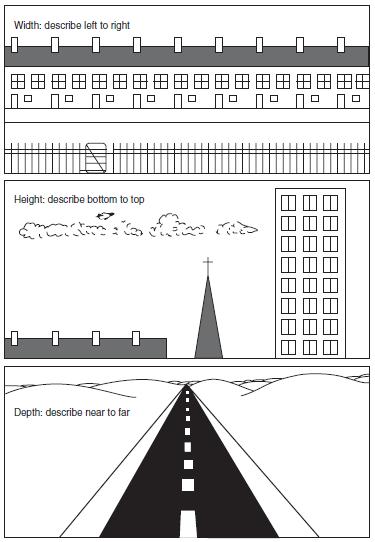

It is all too easy to fall short of an overall picture but to end up instead with some accurately described but separate pieces of jigsaw. The great art, and challenge, of commentary is to fit them together, presenting them in a logically coordinated way which allows your ‘blind friend’ to place the information accurately in their mind's eye. The commentator must include not only the information relating to the scene, but also something about how this information should be integrated to build the appropriate framework of scale. Having provided the context, other items can then be related to it. Early on, it should be mentioned where the commentator's own position is relative to the scene, also giving details of distance, up and down, size (big and small), foreground and background, side to side, left and right, etc. Movement within a scene needs a smooth, logical transition if the listener is not to become hopelessly disorientated.

Content and style

The commentator begins with a ‘scene-set’, saying first of all where the broadcast is coming from, and why. This is best not given in advance by the continuity handover and duplication of this information must be avoided. The listener should be helped to identify with the location, particularly if it is likely to be familiar. The description continues from the general to the particular noting, as appropriate, the weather, the overall impression of lighting, the mood of the crowd, the colour content of the scene and what is about to happen. Perhaps two minutes or more should be allowed for this ‘scene-setting’, depending on the complexity of the event, during which time nothing much may be happening. By the time the action begins the listener should have a clear visual and emotional picture of the setting, its sense of scale and overall ‘feel’. Even so, the commentator must continually refer to the generalities of the scene as well as to the detail of the action. The two should be woven together.

Figure 17.2 The dimensions of commentary. The listener needs three-dimensional information in which to place the action. Such orientation should not be confined to the scene-set but should be maintained throughout the commentary

Time taken for scene-setting does not, of course, apply in the case of news commentary, where one is concerned first and foremost with what is happening. Arriving at the scene of a fire or demonstration, one deals first with the event and widens later to include the general environment. Even so, it is important to provide the detail with its context.

Many commentaries are greatly improved by the use of colour. Colour whether gaudy or sombre is easily recreated in the mind's eye and mention of purple robes, brilliant green plumage, dark grey leaden skies, the blue and gold of ceremonial, the flashes of red fire, the green and yellow banners, or the sparkling white surf – such specific references conjure up the reality much better than the short cut of describing a scene simply as multi-coloured.

In describing the action itself, the commentator should proceed at the same pace as the event, combining prepared fact with spontaneous vision. In the case of a planned sequence as a particular person appears, or slightly in anticipation, reference is made to the appropriate background information, title, relevant history and so on. This is more easily said than done and requires a lot of practice – perhaps using a recorder to help perfect the technique.

News action

With little or no time for scene-setting, it's important to answer the central questions, what's happening, where and why? Here, mood is especially important. Are people in a demonstration angry, dignified or relaxed? Read the banners and placards, describe any unrest or scuffles with police. How are the police reacting? Above all, get the event in proportion – how many people are there? How many stone-throwers? What is their age? Very often at such gatherings there are many inactive bystanders, and these are part of the scene too. At a large riot take a wide view, describing things from the edge not the centre of the action – keep out of the way of petrol bombs or water cannon. Again, it's important that you report what you see. This is not the time for analysis as to reasons or speculation on outcomes. Whether this is a two-minute piece for a bulletin or a half-hour actuality programme, leave me, the listener, with an accurate picture of the event so that I can really appreciate what has happened.

Sports action

The description of sport, even more than that of the ceremonial occasion, needs a firm frame of reference. Most listeners will be very familiar with the layout of the event and can orient themselves to the action so long as it is presented to them the right way round. They need to know which team is playing from left to right; in cricket, which end of the pitch the bowling is coming from; in tennis, who is serving from which court; in horse racing or athletics, the commentator's position relative to the finishing line. It is not sufficient to give this information at the beginning only, it has to be used throughout a commentary, consciously associated with the description of the action.

As with the ceremonial commentator, the sports commentator is keeping up with the action but also noticing what is going on elsewhere – for instance, the injured player or a likely change in the weather. Furthermore, the experienced sports commentator can increase interest for the listener by highlighting an aspect of the event which is not at the front of the action. For example, the real significance of a motor race may be the duel going on between fourth and fifth place; the winner of a 10 000-metre race may already be decided but there can still be excitement in whether the athlete in second place will set a new European record or a personal best.

With slower games, such as cricket, the art is to use pauses in the action interestingly, not as gaps to fill but opportunities to add to the general picture or give further information. This is where another commentator or researcher can be useful in supplying appropriate information from the record books or with an analysis of the performance to date. Long stretches of commentary in any case require a change of voice, as much for the listener as for the commentators, and changeovers every 20–30 minutes are about the norm.

If, for some reason, the commentator cannot quite see a particular incident or is unsure what is happening, it is better to avoid committing oneself. ‘I think that …’ is better and more positive than ‘It looks as though …’. Similarly, it is unwise for a commentator to speculate on what a referee is saying to a player in a disciplinary situation. Only what can be seen or known should be described – the red or yellow card. It is easy to make a serious mistake affecting an individual's reputation through the incorrect interpretation of what may appear obvious. And it must be regarded as quite exceptional to voice a positive disagreement with an umpire or referee's decision. After all, they are closer to the action and may have seen something that the commentator, with a general view, missed. The reverse can also be true, but in the heat of the moment it is sensible policy to give match officials the benefit of any doubt.

Scores and results should be given frequently for the benefit of listeners who have just switched on, but in a variety of styles in order to avoid irritating those who have listened throughout. Commentators should remember that the absence of goals or points can be just as important as a positive scoreline.

Actuality and silence

It may be that, during the event, there are sounds to which the commentary should refer. The difficulty here is that the noisier the environment, the closer on-microphone will be the commentator, so that the background will be relatively reduced. It is essential to check that these other sounds can be heard through separate microphones, otherwise references to ‘the roar of the helicopters overhead’, ‘the colossal explosions going on around me’ or ‘the shouts of the crowd’ will be quite lost on the listener. It is important in these circumstances for the commentator to stop talking and to let the event speak for itself.

There may be times when it is virtually obligatory for the commentator to be silent – during the playing of a national anthem, the blessing at the end of a church service or important words spoken during a ceremonial. Acute embarrassment on the part of the over-talkative commentator and considerable annoyance for the listener will result from being caught unawares in this way. A broadcaster unfamiliar with such things as military parades or church services must be certain to avoid such pitfalls by a thorough briefing beforehand.

The ending

Running to time is helped by having a stopwatch synchronized with the studio clock. This will provide for an accurately timed handback, but if open-ended, the cue back to the studio is simply given at the conclusion of the event.

It is all too easy after the excitement of what has been happening to create a sense of anticlimax. Even though the event is over and the crowds are filtering away, the commentary should maintain the spirit of the event itself, perhaps with a brief summary or with a mention of the next similar occasion. Another technique is radio's equivalent of the television wide-angle shot. The commentator ‘pulls back’ from the detail of the scene, concluding as at the beginning with a general impression of the whole picture before ending with a positive and previously agreed form of words which indicates a return to the studio.

Many broadcasters prefer openings and closings to be scripted. Certainly, if you have hit upon the neat, well-turned phrase, its inclusion in any final paragraph will contribute appropriately to the commentator's endeavour to sum up both the spirit and the action of the hour.

An example

One of the most notable commentators was the late Richard Dimbleby of the BBC. Of many, perhaps his most memorable piece of work was his description of the lying-in-state of King George VI at Westminster Hall in February 1952. The printed page can hardly do it justice, it is radio and should be heard to be fully appreciated. It is old now, but nevertheless it is still possible to see here the application of the commentator's ‘rules’. A style of language, and delivery, that is appropriate to the occasion. A ‘scene-set’ which quickly establishes the listener both in terms of the place and the mood. ‘Signposts’ which indicate the part of the picture being described. Smooth transitions of movement that take you from one part of that picture to another. Researched information, short sentences or phrases, direct speech, colour and attention to detail, all used with masterly skill to place the listener at the scene.

‘It is dark in New Palace Yard at Westminster tonight. As I look down from this old, leaded window I can see the ancient courtyard dappled with little pools of light where the lamps of London try to pierce the biting, wintry gloom and fail. And moving through the darkness of the night is an even darker stream of human beings, coming, almost noiselessly, from under a long, white canopy that crosses the pavement and ends at the great doors of Westminster Hall. They speak very little, these people, but their footsteps sound faintly as they cross the yard and go out through the gates, back into the night from which they came.

They are passing, in their thousands, through the hall of history while history is being made. No one knows from where they come or where they go, but they are the people, and to watch them pass is to see the nation pass.

It is very simple, this lying-in-state of a dead king, and of incomparable beauty. High above all light and shadow and rich in carving is the massive roof of chestnut that Richard II put over the great hall. From that roof the light slants down in clear, straight beams, unclouded by any dust, and gathers in a pool at one place. There lies the coffin of the King.

The oak of Sandringham, hidden beneath the rich golden folds of the Standard; the slow flicker of the candles touches gently the gems of the Imperial Crown, even that ruby that King Henry wore at Agincourt. It touches the deep purple of the velvet cushion and the cool, white flowers of the only wreath that lies upon the flag. How moving can such simplicity be. How real the tears of those who pass and see it, and come out again, as they do at this moment in unbroken stream, to the cold, dark night and a little privacy for their thoughts.’

(Richard Dimbleby)

Coping with disaster

Sooner or later something will go wrong. The VIP plane crashes, the football stadium catches fire, terrorists suddenly appear, a peaceful demonstration unexpectedly becomes violent or spectator stands collapse. The specialist war correspondent or experienced news reporter sent to cover a disaster knows how far to go in describing death and destruction. Sensitivity to the reactions of the listener in describing mutilated bodies or the bloody effect of shellfire is developed through experience and a constant reappraisal of news values. But the non-news commentator must also learn to cope with tragedy. From the crashing of the Hindenburg airship in 1937, and the explosion of the space shuttle, to the destruction of the Twin Towers, commentators are required to react to the totally unforeseen, responding with an instant transition perhaps from national ceremony to fearful disaster. Certain kinds of events such as motor racing and airshows have an inherent capacity for accident, but when terrorists invade a peaceful Olympic Games village commentators normally used to describing the excitement of the track are called on to cope with tensions of quite a different magnitude.

Here is an example of BBC Sports commentator Peter Jones covering a football match at Hillsborough Stadium, Sheffield. The game had only just begun when more people crowding into the ground suddenly caused such a crush in the stands that supporters were climbing the fences and invading the pitch. The match was stopped and a few moments later:

‘At the moment there are unconfirmed reports, and I stress unconfirmed reports, of five dead and many seriously injured here at Hillsborough. Just to remind you what happened – after five minutes, at the end of the ground to our left where the Liverpool supporters were packed very tightly – and the report is that one of the gates in the iron fence burst open – supporters poured on the pitch. Police intervened and quite correctly the referee took the police advice and took both teams off. Since then we've had scenes of improvised stretchers with the advertising hoardings being torn up, spectators have helped, we've got medical teams, oxygen cylinders, a team of fire brigade officers as well to break down the fence at one end to make it easier for the ambulances to get through and we've got bodies lying everywhere on the pitch.’

(Courtesy of BBC Sport)

Remembering that his commentary was being heard by the families and friends of people at the match, it was important here to describe the early casualty reports as ‘unconfirmed’ and also to avoid any attempt at identifying the cause of the situation or, worse, to apportion blame. Commentators do well to report only what they can personally see.

So what should the non-specialist do? Here are some guidelines:

![]() Keep going if you can. A sense of shock is understandable, but don't be so easily deterred by something unusual that you hand back to the studio. Even if your commentary is not broadcast ‘live’ it could be crucial for later news coverage.

Keep going if you can. A sense of shock is understandable, but don't be so easily deterred by something unusual that you hand back to the studio. Even if your commentary is not broadcast ‘live’ it could be crucial for later news coverage.

![]() There's no need to be ashamed of your own emotions. You are a human being too and if you are horrified or frightened by what is happening, say so. Your own reaction will be part of conveying that to your listener. It's one thing to be professional, objective and dispassionate at a planned event, it is quite another to remain so during a sudden emergency.

There's no need to be ashamed of your own emotions. You are a human being too and if you are horrified or frightened by what is happening, say so. Your own reaction will be part of conveying that to your listener. It's one thing to be professional, objective and dispassionate at a planned event, it is quite another to remain so during a sudden emergency.

![]() Don't put your own life, or the lives of others, in unnecessary danger. You may from the best of motives believe that ‘the show must go on’, but few organizations will thank you for the kind of heroics which result in your death. If you are in a building which is on fire, say so and leave. If the bullets are flying or riot gas is being used in a demonstration, take cover. You can then say what's happening and work out the best vantage point from which to continue.

Don't put your own life, or the lives of others, in unnecessary danger. You may from the best of motives believe that ‘the show must go on’, but few organizations will thank you for the kind of heroics which result in your death. If you are in a building which is on fire, say so and leave. If the bullets are flying or riot gas is being used in a demonstration, take cover. You can then say what's happening and work out the best vantage point from which to continue.

![]() Don't dwell on individual anguish or grief. Keep a reasonably ‘wide angle’ and put what is happening in context. Remember the likelihood that people listening will have relatives or friends at the event.

Don't dwell on individual anguish or grief. Keep a reasonably ‘wide angle’ and put what is happening in context. Remember the likelihood that people listening will have relatives or friends at the event.

![]() Let the sounds speak for themselves. Don't feel you have to keep talking, there is much value in letting your listener hear the actuality – gunfire, explosions, crowd noise, shouts and screams.

Let the sounds speak for themselves. Don't feel you have to keep talking, there is much value in letting your listener hear the actuality – gunfire, explosions, crowd noise, shouts and screams.

![]() Don't jump too swiftly to conclusions as to causes and responsibility. Leave that to a later perspective. Stick with observable events, relay the facts as you see them.

Don't jump too swiftly to conclusions as to causes and responsibility. Leave that to a later perspective. Stick with observable events, relay the facts as you see them.

![]() Above all, arrive at a station policy for this sort of coverage well before any such event takes place. Get the subject on the agenda in order to agree emergency procedures.

Above all, arrive at a station policy for this sort of coverage well before any such event takes place. Get the subject on the agenda in order to agree emergency procedures.