18

Music recording

There are three questions that a producer should ask before becoming involved in the production of any music.

First, is the material offered relevant to programme needs? The technically minded producer, audiophile or engineer can easily create reasons for recording a particular music occasion other than for its value as good programming. It may represent an attractive technical challenge or be the sort of concert which at the time seems a good idea to have ‘in the can’. Alternatively, the desire to record a particular group of performers may outweigh considerations of the suitability of what they are playing. Sometimes musicians are visually persuasive but aurally colourless, as with many club performers dependent on an atmosphere difficult to reproduce on radio. To embark on music with little prospect of broadcasting it is a speculative business and the radio producer should not normally commit resources unless it's known, perhaps only in outline, how the material is to be used.

The second question asks whether the standard of performance is good enough for broadcasting. There cannot be a single set of objective criteria for standards since much depends on the programme's purpose and context. A national broadcaster will undoubtedly demand the highest possible standards. Regionally and locally, there is an obligation to broadcast the music making of the area, which will almost certainly be of less than international excellence. The city orchestra, college swing band, amateur pop group, all have a place in the schedules, but for broadcasting to a general audience, as opposed to a school concert which is directed only to the parents of performers, there is a lower limit below which the standard must not fall. In identifying this minimum level, the producer has to decide whether what is being broadcast is primarily the music, the musician or the occasion. Certainly, one should not go ahead without a clear indication of the likely outcome – new groups should be auditioned first, preferably ‘live’ rather than from a submitted disc or cassette. If the technical limits of performance are apparent, musicians should be persuaded to play items that lie within their abilities. Simple music well played is infinitely preferable to the firework display that does not come off.

And finally, is the recording or broadcast within the technical capability of the station? Even at national level there are limits to what can be expended on a single programme. Numbers and types of microphones, the best specification for stereo lines, special circuits, engineering facilities at a remote OB site, the availability of more than one echo source and so on – these are considerations which affect what the listener will hear and will therefore contribute to an appreciation of the performer. The broadcaster has an obvious obligation to artists to present them in the most appropriate manner without the intervention of technical limits. This presupposes that the producer knows exactly what is involved in any given situation and, for example, understands the implications of a ‘live’ concert where the members of a pop group sing as they play, where public address relay is present, or hypercardioid, variable pattern or tie-clip microphones are required to do justice to a particular sound balance. Small programme-making units should avoid taking on more than they can adequately handle, and instead should stay within the limits of their equipment and expertise. Much better for a local station to refuse the occasional music OB as beyond its technical scope than it should broadcast a programme that it knows could have been improved, given better equipment. Alternatively, if a station is not equipped or staffed to undertake outside music recording, it could consider contracting the work out to a specialist facilities company, with the station retaining editorial control.

The remainder of this chapter is directed to help producers in their understanding of some of the technical factors of music recording.

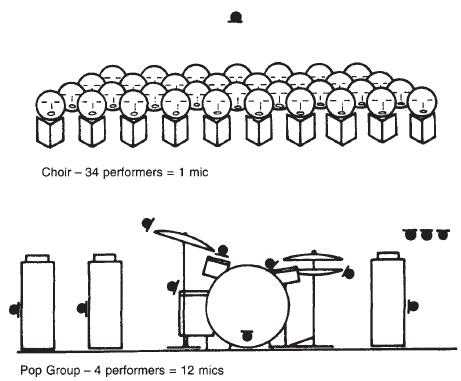

Figure 18.1 The technical complexity of broadcasting live music is not related to how many performers there are. The producer must decide whether adequate programme standards can be achieved within the available resources

The philosophy of music balance is divided into two main groups – first, the reproduction of a sound which is already in existence and, second, the creation of a synthetic overall balance which exists only in the composer's or arranger's head and subsequently in the listener's loudspeaker.

Reproduction of internal balance

Where the music created results from a carefully controlled and self-regulating relationship between the performers, it would be wrong for the broadcaster to alter what the musicians are trying to achieve. For example, the members of a string quartet are sensitive to each other and adjust their individual volume as the music proceeds. They produce a varying blend of sound that is as much part of the performance as the notes they play or the tempo they adopt. The finished product of the sound already exists and the art of the broadcaster is to find the place where the microphone(s) can most faithfully reproduce it. Other examples of internally balanced music are symphony orchestras, concert recitalists, choirs and brass bands. The dynamic relationship between the instruments and sections of a good orchestra is under the control of its conductor; the broadcaster's task is to reproduce this interpretation of the music and not create a new sound by boosting the woodwind or unduly accentuating the trumpet solo. Since the conductor controls the internal balance by what he or she hears, it is in this area that one searches initially for the ‘right’ sound. Using a ‘one-mic balance’ or stereo pair, the rule of thumb is to place it with respect to the conductor's head – ‘three metres (10 feet) up and three metres (10 feet) back’.

Similarly, the conductor of a good choir will listen, assess and regulate the balance between the soprano, contralto, tenor and bass parts. If the choir is short of tenors and this section needs reinforcing, this adjustment can of course be made in the microphone balance. But this is at once to create a sound not made simply by the musicians and raises interesting questions about the lengths to which broadcasters may go in repairing the deficiencies of performers.

It is possible to ‘improve’ a musician's tone quality, to clarify the diction of a choir or to correct an unevenly balanced group. With a multi-track recorder it is even possible to correct a soloist's late entry by moving that track forward in time. The ultimate in such cosmetic treatment is to use the techniques of the recording studio to so enhance a performer's work that it becomes impossible for them ever to appear ‘live’ in front of an audience, a not-unknown situation. But while it is entirely reasonable to make every possible adjustment in order to obtain the best sound from a school orchestra, it would be unthinkable to tamper with the performance of an artist who had a personal reputation. It is in the middle ground, including the best amateur musicians, where the producer is required to exercise this judgement – to do justice to the artist but without making it difficult for the performer in other circumstances.

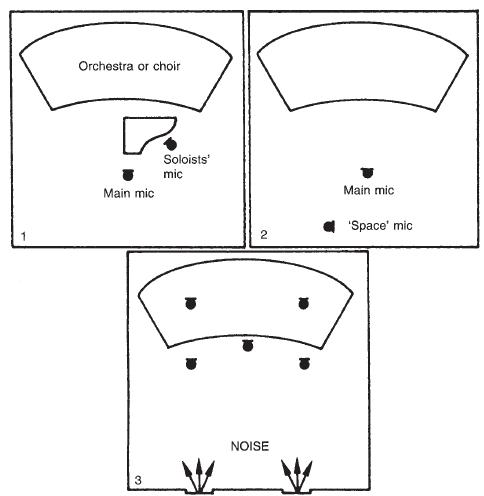

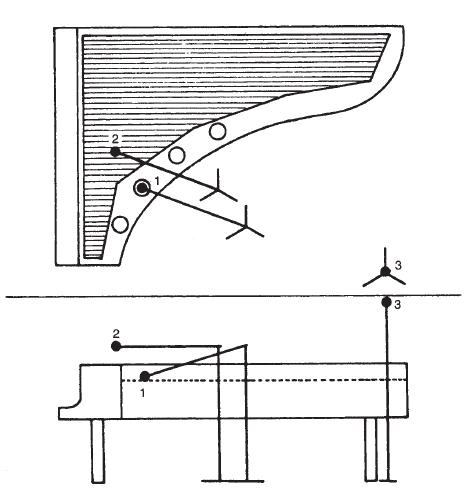

Figure 18.2 Basic considerations for mic placement with an internally balanced group. 1. Mic balance suitable under low noise conditions in a good acoustic. A soloist's mic or occasional ‘filler’ mic may be added. 2. In too ‘dry’ an acoustic, a space mic is added to increase the pick-up of reflected sound. 3. Under conditions of unacceptable ambient noise, the microphones are moved closer to the source and increased in number to preserve the overall coverage. It may be necessary to add artificial reverberation

The foregoing assumes that the music is performed in a hall that has a favourable acoustic. Where this is not the case, steps have to be taken to correct the particular fault. For example, in too ‘dry’ an acoustic, some artificial reverberation will need to be added, preferably on-site at the time of recording, although it is possible for it to be added later. Alternatively, a ‘space’ microphone can be used to increase the pick-up of reflected sound. If the hall is too reverberant or the ambient noise level, from air-conditioning plant or outside traffic, is unacceptably high, the microphone should be moved closer to the sound source. If this tends to favour one part at the expense of another, further microphones are added to restore full coverage. The best sound quality from most instruments and ensembles is to be found not simply in front of them, but above them. A good music studio will have a high ceiling and the microphone for an internally balanced group will be kept well above head height. As mentioned previously, the standard starting procedure is to place a main microphone ‘three metres up and three metres back’ from the conductor's head, with a second microphone perhaps further back and a little higher. The outputs of the two microphones are then compared. The one giving the better overall blend without losing the detail then remains and the other microphone is moved to another place for a second comparison. An alteration in distance of even a few centimetres can make a significant difference to the sound produced. Hence the development of the Decca ‘tree’, which consists of three omni mics placed in a horizontal equilateral triangle two metres apart above the conductor's head. They are panned left, centre and right. This helps to avoid the effects of either the reinforcement or the phase cancellation of the reflected sound, whereby mono microphones are best placed asymmetrically within a hall, off the centre line. Similarly, one avoids the axis of a concave surface such as a dome.

The process of mic combining and comparison continues until no further improvement can be obtained. It is essential that such listening is done with reference to the actual sounds produced by the musicians. It is important that producers and sound balance engineers do not confine themselves to the noises produced by their monitoring equipment, good though they may be, but listen in the hall to what the performers are actually doing.

Having achieved the best placing for the main microphone, soloists’, ‘filler’ or ‘space’ mics may be added. These additional microphones must not be allowed to take over the balance nor should their use alter the ‘perspective’ during a concert. For a group that is balanced internally, the only additional control is likely to be a compression of the dynamic range as the music proceeds. An intelligent anticipation of variations in the dynamics of the sound is required and although a limiter/compressor will avoid the worst excesses of overload, it can also iron out all artistic subtlety in the performance. There is no substitute for a manual control that takes account of the information from the musical score and is combined with a sensitive appreciation of what comes out of the loudspeaker.

The aim is to broadcast the music together with whatever atmosphere may be appropriate. To secure the confidence of the conductor, bandmaster or leader, it is good practice to invite them into the sound mixing and monitoring area to listen to the balance achieved during rehearsal. It should be remembered that since conductors normally stand close to the musicians, they are used to a fairly high sound level and the playback of rehearsal recordings should take this into account. Recordings should not as a rule be played back into the room in which they were made, since this can lead to an undue emphasis of any acoustic peculiarity. A final balance should also be monitored at low level, at what more closely resembles domestic listening conditions. This is particularly important with vocal work, when the clarity of diction may suffer if the end result is only judged at high level.

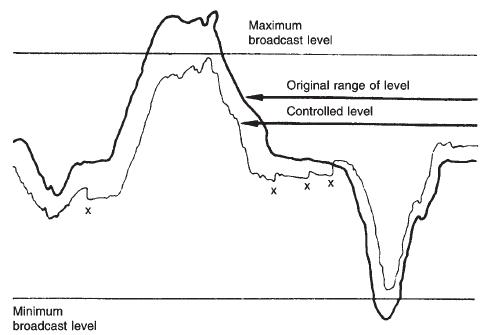

Figure 18.3 Dynamic compression. The range of loudness in the studio can easily rise above the maximum and fall below the minimum levels acceptable to the broadcast system. By anticipating a loud passage, the main fader is used to reduce the level before it occurs. Similarly, the level prior to a quiet part is increased. Faders generally work in small steps, each one introducing a barely perceptible change (X)

Creation of a synthetic balance

Whereas the reproduction of an existing sound calls for the integration of performance and acoustic using predominantly one main microphone, the creation of a synthetic balance, which in reality exists nowhere, requires the use of many microphones to separate the musical elements in order to ‘treat’ and reassemble them in a new way. For example, a concert band arrangement calling for a flute solo against a backing from a full brass section would be impossible unless, for the duration of the solo, the flute can be specially favoured at the expense of the brass. Achieving this relies on the ability to separate the flute from everything else in such a way that it can be individually emphasized without affecting the sound from other instruments. The factors involved in achieving this separation are: studio layout, microphone types, source treatment, mixing technique and recording technique.

Studio layout

The physical arrangement of a music group has to satisfy several criteria, some of which may conflict:

1 To achieve ‘separation’, quiet instruments and singers should not be too close to loud instruments.

2 The spatial arrangement must not inhibit any stereo effect required in the final balance.

3 The conductor or leader must be able to see everyone.

4 The musicians must be able to hear themselves and each other.

5 Certain musicians will want to see other musicians.

6 If an audience is present, the group will need to play to ‘the front’.

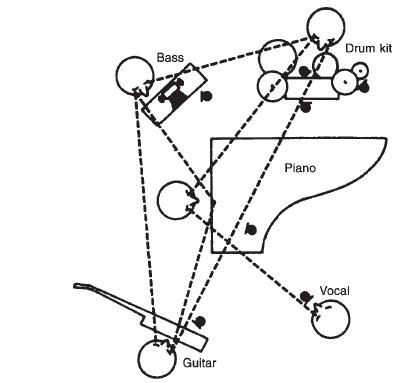

Figure 18.4 Studio layout. The musicians need to see each other, and the microphones placed so as to avoid undue pick-up of other instruments

The producer should not force players to adopt an unusual layout against their will, since the standard of performance is likely to suffer. Any difficulty of this kind has to be resolved by suggesting alternative means of meeting the musical requirements. For example, a rhythm section of piano, bass, drums and guitar needs to be tightly grouped together so that they can all see and hear each other. If there is a tendency for them to be picked up on the microphones of adjacent instruments, then working closely to highly directional mics may improve the separation, or they may need to be screened off. If this in turn affects their or other musicians’ ability to see or hear, the sight-line can be restored by the use of screens with inset glass panels, and aural communication maintained by means of headphones – or a foldback speaker on the floor near them – fed with whatever mix of other sources they need. It's worth noting that working simply from a floor plan may inhibit thinking in three dimensions. The solution to a sight-line problem may be to use rostra or staging to raise, say, a brass section – this can improve the separation by keeping it off other mics, which are pointing downwards.

Left to themselves, musicians often adopt the layout usual to them for cabaret or stage work. This may be unsuitable for broadcasting and it is essential that the producer knows the instrumentation detail beforehand in order to make positive suggestions for the studio arrangements. It's obviously important to know whether bass and guitar players have an electric or acoustic instrument. Also, how much ‘doubling’ is anticipated – that is, one musician playing more than one instrument, sometimes within the same musical piece, and whether the players are also to sing. This information is also useful in knowing how many music stands to provide.

It is desirable to avoid undue movement in the studio during recording or transmission, but it may be necessary to ask a particular musician to move to another microphone, for example for a solo. It is also usual to ask brass players to move into the microphone slightly when using a mute. This avoids opening the fader to such an extent that the separation might be affected.

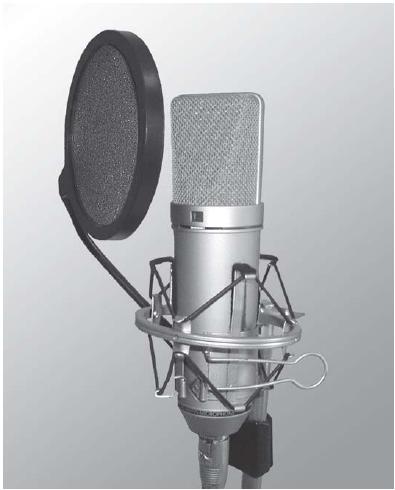

Figure 18.5 A high-quality Neumann condenser speech/vocal mic with a fine gauze ‘pop-stopper’ to prevent breath blasts causing audible pops

Microphones for music

As an aid in achieving separation, the sound recordist's best friend is the directional microphone. The physical layout in the studio is partly arrived at in the light of what microphones are available. A ribbon microphone with its figure of eight directivity pattern is most useful for its lack of pick-up on the two sides. Used horizontally just above a flute or piano, it is effectively dead to other instruments in the same plane. A cardioid microphone gives an adequate response over its front 180° and will reject sounds arriving at the back – good for covering a string section. A hypercardioid microphone will narrow the angle of acceptance, giving an even more useful area of rejection. Condenser or electret types of microphone with variable directivity patterns are valuable for the flexibility they afford in being adjustable – often by remote control – to meet particular needs.

Mics for singers working very close to them will need additional windshield or ‘pop-stoppers’ to prevent blasts of breath causing audible noise.

The presenter of a live music show with an audience will probably need his or her mic to be fed to a public address system as well as to the broadcaster's mixer. Careless PA suffers from the all too familiar howl-round problem, even with a mixer desk that provides an anti-howl facility by tuning out the most susceptible frequency. However, a personal radio mic is a great help – provided that the sound mixer can see the stage. PA mixing is best done in the hall itself, so that the operator hears what the live audience hears and can take immediate action in the event of the onset of a ‘howl’. If this is not possible, a video link is extremely useful in allowing both the PA and the broadcast mixers to see what the performers are doing. The producer should also decide if the presenter needs talkback via an earphone.

The wide operatic platform can be covered by a suspended stereo pair or a row of three panned, front-of-stage mics. The low ‘boundary effect’ mic is particularly effective in this context, although prone to footstep sounds.

The closer a microphone is placed to an instrument, the greater the relative balance between it and the sounds from other sources. However, while separation is improved, other effects have to be considered:

1 The pick-up of sound very close to an instrument may be of inferior musical quality. It can be uneven across the frequency range or sound ‘rough’ due to the reproduction of harmonics not normally heard.

2 There may be an undue emphasis of finger noise or the instrument's mechanical action.

3 The volume of sound may produce overload distortion in the microphone or in the subsequent electronics.

4 Movement of the player relative to the microphone becomes very critical, causing significant variations in both the quantity and quality of the sound.

5 Close microphone techniques require more microphones and more mixing channels, thus increasing the complexity of the operation and the possibility of error.

The choice and placing of microphones around individual instruments is a matter of skill and judgement by the recording engineer. But no matter how complex the technical operation, the producer must also be aware of other considerations. Technicalities such as the changing of microphones, alterations to the layout and the running of cables or audio feeds should not be allowed to interfere unduly with the music-making or human relations aspects. It is possible to be technically so pedantic as to inhibit the performance. If major changes in the studio arrangements are required, it is much better to do them while the musicians are given a break. Under these circumstances the broadcaster has an obvious additional responsibility to safeguard instruments left in the studio.

Figure 18.6 Piano balance. Typical microphone positions for different styles of music. 1. Emphasizes percussive quality for pop music and jazz. 2. Broader intermediate position for light music. 3. Full piano sound for recitals and other serious or classical music

The ultimate in separation is to do away with the microphone altogether. This is possible with certain electronic instruments where their output is available via an appropriately terminated lead, as well as acoustically for the benefit of the player and other musicians. The lead should be connected through a ‘direct inject’ box to a normal microphone input cable. Used particularly in conjunction with electric guitars, the box obviates the hum, rattles and resonances often associated with the alternative method, namely placing a microphone in front of the instrument's loudspeaker.

A further point in the use of any electrically powered instrument is that it should be connected to a studio power socket through a mains isolating transformer. This will protect the power supply in the event of a failure within the instrument and will exclude the possibility of an electrocution accident – so long as the studio equipment and the individual instrument are correctly wired and properly earthed. Faulty wiring or earthing arrangements can cause an accident, as in the event of a performer touching simultaneously two ‘earths’ (‘grounds’) – for example, an instrument and a microphone stand – which in fact are at a different potential. While comparatively rare, it is a matter that needs attention in the broadcasting of amateur pop groups using their own equipment. The broadcasting organization is legally responsible for the safety of performers and contributors while on their premises or under their supervision.

Having turned the acoustic sound into electrical output, a number of treatments may now be applied to individual sources, some of which can affect the separation. These include frequency control, dynamic control and echo.

Frequency control

The tone quality of any music source can be altered by the emphasis or suppression of a given portion of its frequency spectrum. Using a graphic equalizer, the EQ on the mixer channel or other frequency discriminating device, a singer's voice is given added ‘presence’, and clarity of diction is improved, by a lift in the frequency response in the octave between 2.8 and 5.6 kHz. A string section can be ‘thickened’ and made ‘warmer’ by an increase in the lower and middle frequencies, while brass is given greater ‘attack’ and a sharper edge by some ‘top lift’. It should be noted, however, that in effectively making the microphone for the brass section more sensitive to the higher frequencies, spillover from the cymbals is likely to increase and separation in this direction is therefore reduced. Fairly savage control is often applied to jazz or rhythm piano to increase its percussive quality. It is also useful on a one-microphone balance, particularly on an outside broadcast, to reduce any resonance or other acoustic effect inherent in the hall.

Dynamic control

This can be applied automatically by inserting a compressor/limiter device in the individual microphone chain. On a digital desk this facility, together with a noise gate, is likely to be found on each channel. Once set, the level obtained from any given source will remain constant – quiet passages remain audible, loud parts do not overload. It becomes impossible for the flute to be swamped by the brass. Because of the economics of popular music, commercial recording companies have attained a high degree of sophistication in the use of dynamic control. This is unlikely to be reached by most broadcasters, who are unable to go to such lengths in recording their music. However, devices of this type can save studio time and their progressive application is likely. Variations include a ‘voice-over’ facility that enables one source to take precedence over another. Originally intended for DJs, its obvious use is in relation to singers and other vocalists, but it can be applied to any source relative to any other. Computerized music desks can be programmed to store in a memory the changing mix required throughout a performance. In the final take, the basics can be left to look after themselves.

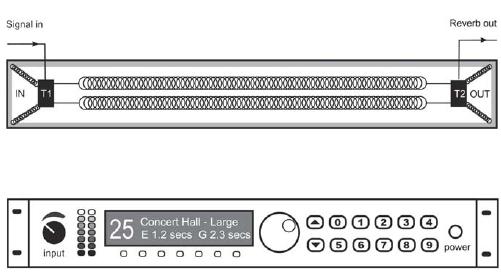

Figure 18.7 Mechanical and digital methods of creating echo. The spring device delays the programme signal sent to it, returning it to the mixing desk as reverberation. The digital effects box offers a large range of frequency and delay options to colour the original sound

Echo

The echo effect, more correctly described as reverberation, used to be generated in an empty room, but today's digital effects equipment is so versatile that any kind of echo can be created electronically through a number of controls and presets which affect the duration, type, mix and decay characteristic of the reverberation. It is also possible to alter the frequency response, thereby producing any acoustic from a boxy telephone booth to a cave or cathedral. This is illustrated on the CD. Modern desks not only offer echo and delay, but facilities may also include dynamic compression, equalization and noise reduction – even of a specific frequency – making it especially useful in controlling the howl-round of PA. A digital mixer may have all these facilities on every channel.

The output from a source can be made to vibrate a mechanical plate or spring, the vibrations travelling through it to a transducer, which converts them back into electrical energy, returning as echo to the mixing desk. Equivalent to a two-dimensional room, the reverberation time is adjustable depending on the mechanical damping applied. Some such devices are in portable form and are often preferred for ‘retro’ OB applications.

When echo is added to solo singers’ voices it is wise to let them listen on headphones, since they will almost certainly want to adjust their phrasing to suit the new sound.

Channel delay

The clever way of overcoming the effect of altering the perspective when opening up an individual ‘spot’ mic is to delay the output of the mic by the same amount as the sound of that source coming through the main mic. For example, if an orchestral clarinet is 40 feet from the main mic, the time taken for its sound to reach that microphone is some 40 milliseconds (rule of thumb: sound travels 1100 feet/second or 1 foot/ms). Therefore, with a delay of 40 ms in the close clarinet mic, its sound is heard as if it were still 40 feet away. On opening up its own mic, the perceived effect is that the instrument is ‘louder but not closer’. This is yet another facility that a digital mixer can offer on every channel.

Mixing technique

Before mixing a multi-microphone balance, each channel should be checked for delivering its correct source, with adequate separation from its neighbours, having the desired amount of ‘treatment’ and producing a clear distortion-free sound. It is a sensible procedure to label the channel faders with the appropriate source information – solo vocal, piano, lead guitar and so on. For a stereo balance it is necessary to be clear about the placing of each instrument in the stereo picture. Stereo microphones are physically adjusted to spread their output across the required width of the picture, and the mono microphone ‘pan-pots’ set so that their placement coincides with that provided by any stereo microphone covering the same source. It is possible to create a stereo balance using only monophonic microphones by ‘spotting’ them across the stereo picture, but it is an advantage to have at least one genuine stereo channel, even if it is only the echo source.

Microphones should be mixed first in their ‘family’ groups. The rhythm section, backing vocals or brass is individually mixed to obtain an internal balance. The sections are then added to each other to obtain an overall mix. Music desks allow their channels to be grouped together so that sections can be balanced relative to each other by the operation of their ‘group’ fader without disturbing the individual channel faders. Successful mixing requires a logical progression, for if all the faders are opened to begin with, the resulting confusion can be such that it is very difficult to identify problems. It is important to arrive at a trial balance fairly quickly, since the ear will rapidly become accustomed to almost anything. The overall control is then adjusted so that the maximum level does not exceed the permitted limit.

The prime requirement for a satisfying music balance is that there should be a proper relationship between melody, harmony and rhythm. Since the group is not internally balanced, listening on the studio floor will not indicate the required result. Only the ‘hands-on’ person manipulating the faders and listening to the loudspeaker is in a position to arrive at a final result. The melody will almost certainly be passed around the group, and this will need very precise operation of the faders. If the lead guitar takes the tune from an upbeat, that fader must be opened further from that point – no earlier, otherwise the perspective will alter. At the end of that section the fader must be returned to the normal position to avoid loss of separation. It is probable that alterations to a source making use of echo will need a corresponding and simultaneous variation in the echo return channel. It is a considerable help, therefore, to have an elementary music score or ‘lead sheet’ which indicates which instrument has the melody at any one time. If this is not provided by the musical director, the producer should ensure that notes are taken at the rehearsal – for example, how many choruses there are of a song, at what point the trumpets put their mutes in and, perhaps more importantly, when they take them out again, when the singer's microphone has to be ‘live’ and so on. A professional music balance operator quickly develops a flair for reacting to the unexpected but, as with most aspects of broadcasting, some basic preparation is only sensible.

It is important that faders that are opened to accentuate a particular instrument are afterwards returned to their normal setting. Unless this is done it will be found that all the faders are gradually becoming further and further open, with a compensating reduction of the overall control. This is clearly counter-productive and leads to a restriction in flexibility as the channels run out of ‘headroom’.

As with all music balance work, the mixing must not take place only under conditions of high-level monitoring. The purpose of having the loudspeaker turned well up is so that even small blemishes can be detected and corrected. But from time to time the listening level must be reduced to domestic proportions to check particularly the balance of vocals against the backing, and the acceptable level of applause. The ear has a logarithmic response to volume and is far from being equally sensitive to all the frequencies of the musical spectrum. This means that the perceived relationship between the loudness of different frequencies heard at high level is not the same as when heard at a lower level. Unless the loudspeaker is used with domestic listening in mind as well as for professional monitoring, there will be a tendency as far as the listener at home is concerned to underbalance the echo, the bass and the extreme top frequencies. For this reason, many professional studios check the final mix on a simple domestic loudspeaker.

Recording technique

The successful handling of a music session requires the cooperation of everyone involved. There are several ways of actually getting the material recorded and the procedure to be adopted should be agreed at the outset.

The first method is obviously to treat a recording in the same way as a live transmission. One starts when the red light goes on and continues until it goes out. This will be the procedure at a public concert when, for example, no retakes are possible.

Second, a studio session with an audience present. Minor faults in the performance or mixing will be allowed to pass but the producer must decide when something has occurred that necessitates a retake. The audience may be totally unaware of the problem, but someone will have lightly and briefly to explain the existence of ‘a gremlin’ and quickly brief the musical director on the need to retake from point A to point B.

Third, without an audience the musicians can agree to use the time as thought best. This may be to rehearse all the material and then to record it, or to rehearse and record each individual item. In either case, breaks can be taken as and when decided by the producer in consultation with the musical director. A music producer must, of course, be totally familiar with any agreements with the performers’ unions that are likely to affect how a session is run.

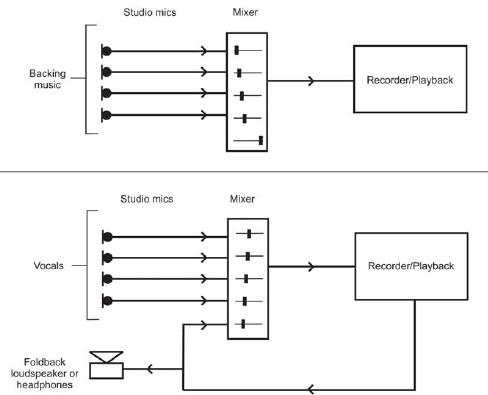

Fourth, to record the most material in the shortest time or to accommodate special requirements, the music may be ‘multi-tracked’. This means that instead of immediately arriving at a final mix, the individual instruments or groups of channels are recorded as separate tracks on a multi-track recorder. In the same way that digital mixers can be linked together to provide greater capacity, three 24-track recorders may be linked to create 72 tracks if required. Digital recording in this way offers a wide range of signal manipulation, monitoring, auto-location and editing. Some tracks can be set to play while others record, so enabling musicians to record their contribution without the necessity of having all the performers present simultaneously. It also permits ‘doubling’ – that is, the performing of more than one role in the same piece of music. This double-tracking is most often used for an instrumental group who also sing. The musicians first play the music – either conventionally recorded or multi-tracked – and when this is played back to them on headphones, they add the vocal parts. These are recorded on separate tracks or mixed with the music tracks to form a final recording. This process can be repeated to enable singers to sing with themselves as many times as is required to create the desired sound. An added advantage of multi-tracking is that any mistake does not spoil the whole performance – a retake may only be required to correct the individual error. The subsequent ‘mixing down’ or ‘reduction’ of many tracks is a relatively straightforward process, giving the producer the opportunity to tidy up the performance. Many is the recording session when it was said, ‘We'll sort it out in post-production.’ But then what if it is ‘live’?

Figure 18.8 Simple ‘doubling’. The musicians first record a ‘backing track’. This is then played back so that it is heard on the studio foldback speaker (or headphones) while the musicians provide another four tracks. This can be mixed with the backing to provide a single track or kept as eight separate tracks for later mixdown

Since recording at different times represents total separation, multi-tracking techniques can solve other problems. For instance, the physical separation or screening of loud instruments such as a drum kit can be avoided by recording the rhythm section separately – usually first, in order to keep subsequent performers in sync. It is an especially useful technique to apply to a music recording which has to be done in a small, non-purpose-built studio, and even working in four tracks can help to produce a more professional sound.

A point worth noting by studios unable to afford the latest in sophisticated stereo recording equipment is that a good domestic video recorder connected to a digital processor is capable of excellent results.

Production points

Essentially, the producer's job is to obtain a satisfactory end product within the time available and above all to avoid running into overtime, which with professional musicians is expensive. Neither do musicians appreciate an oppressively hard taskmaster, so that the session ends with time to spare and everyone is relieved to get out. The producer must remember that all artists need encouragement and that ‘production’ has a positive duty in helping them give the best performance possible.

Finally, some general points:

![]() Avoid using the talkback into the studio to make disparaging comments about individual performers. Instead, direct all remarks to the conductor or group leader via a special headphone feed, or better still by going into the studio for a personal talk.

Avoid using the talkback into the studio to make disparaging comments about individual performers. Instead, direct all remarks to the conductor or group leader via a special headphone feed, or better still by going into the studio for a personal talk.

![]() Foster a professionally friendly atmosphere and sound relaxed even when under pressure. Often acting as the mediator between the performers and the technical staff, explain delays and agree new time-scales.

Foster a professionally friendly atmosphere and sound relaxed even when under pressure. Often acting as the mediator between the performers and the technical staff, explain delays and agree new time-scales.

![]() Anticipate the need for breaks and rest periods. During these times it is often sensible to invite the MD or group leader into the control cubicle to hear the recorded balance and discuss any problems.

Anticipate the need for breaks and rest periods. During these times it is often sensible to invite the MD or group leader into the control cubicle to hear the recorded balance and discuss any problems.

![]() Avoid displaying a musical knowledge which, while attempting to impress, is based on uncertain foundations. ‘Can we have a shade more “arco” on the trombones?’ is a guaranteed credibility loser.

Avoid displaying a musical knowledge which, while attempting to impress, is based on uncertain foundations. ‘Can we have a shade more “arco” on the trombones?’ is a guaranteed credibility loser.

![]() Make careful rehearsal notes for the recording or transmission, and take details of the final timings and any retakes for subsequent editing.

Make careful rehearsal notes for the recording or transmission, and take details of the final timings and any retakes for subsequent editing.

![]() When an audience is present, decide how it is best handled and what kind of introduction and warm-up is appropriate – and get them to switch off their mobile phones. This is often the producer's job.

When an audience is present, decide how it is best handled and what kind of introduction and warm-up is appropriate – and get them to switch off their mobile phones. This is often the producer's job.

![]() Resolve the various conflicts that arise – whether the air-conditioning or heating is working properly, whether the lights are too bright or whether the banging in another part of the building can be stopped. Remember other needs – ashtrays, drinking water, lavatories, telephones.

Resolve the various conflicts that arise – whether the air-conditioning or heating is working properly, whether the lights are too bright or whether the banging in another part of the building can be stopped. Remember other needs – ashtrays, drinking water, lavatories, telephones.

![]() When a retake is required, make a positive decision and communicate it quickly to the musical director. The producer exercises the broadcaster's normal editorial judgement and is responsible for the quality of the final programme.

When a retake is required, make a positive decision and communicate it quickly to the musical director. The producer exercises the broadcaster's normal editorial judgement and is responsible for the quality of the final programme.

![]() Ensure that the musicians are paid – those performers who signed a contract and made the music and, through the appropriate agencies, those who wrote, arranged and published the work still in copyright.

Ensure that the musicians are paid – those performers who signed a contract and made the music and, through the appropriate agencies, those who wrote, arranged and published the work still in copyright.

![]() After the session say thank you – to everyone.

After the session say thank you – to everyone.