7

Broadcast Regulations

This chapter surveys broadcast regulations and focuses on

• modifications of the 1996 Telecommunications Act regulatory framework

• FCC licensing and reporting requirements

• FCC policies pertaining to ownership, programming, announcements, commercials, and operating requirements

• FCC regulations on indecency, violence, contests, hoaxes, and political campaigns

Historically, broadcasting has been the most heavily regulated mass medium. Broadcast regulation was based upon concepts of “public interest” and scarcity, which meant, simply, that there were more applicants for licenses than there were available frequencies. In the 1980s, a deregulation frenzy swept the federal government, and the “scarcity” rationale for regulation was declared by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to be no longer valid.

In the early 1990s, the relaxation of formal broadcast regulation continued. Ownership rules were changed in 1991 to permit duopoly, the common ownership of more than one station in the same class of service in the same market. Deregulation casualties of the 1980s and 1990s included long-standing FCC rules, such as the Financial Interest and Syndication Rules (Fin-Syn), the Prime-Time Access Rule (PTAR), the Fairness Doctrine, the Personal Attack Rule, and the Political Editorial Rules. In February 1996, the Congress enacted, and the President signed, the Telecommunications Act of 1996.1

This new law was a sweeping revision of the 1934 Communications Act. However, its principal long-term impact has been on the ownership face of the industry. The law should more appropriately be called the “Consolidation Act of 1996,” because it has permitted concentration of electronic media ownership at the national and local levels. And that consolidation theme has been continued and expanded since passage of the act.2

BACKGROUND

During the early days of broadcasting, there were very few rules to follow. Anyone who wanted to transmit a broadcast signal on any frequency could do so, thus creating a jamming effect on frequencies carrying more than one station.

After years of discussion and compromise among all factions involved in this growing industry, Congress passed the Radio Act of 1927. The act provided for the formation of a Federal Radio Commission (FRC), comprising five persons appointed by the President, one of whom would be selected as chairman. The FRC was to oversee broadcasting on a trial basis for one year. At the end of the year, its term was extended and it continued in effect until 1934.

It soon became apparent that broadcasting needed a new and more comprehensive regulatory agency. In February 1934, President Franklin D. Roosevelt sent to Congress a proposal to create an agency to be known as the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and to bring all means of electronic communication under the jurisdiction of this one agency. The Commission would be composed of seven members appointed by the President, with the advice and consent of the Senate. One member would be designated as chairman by the President.

Today, the FCC is a five-member body, but that is not the only change. Under Chairman Mark Fowler (1981–1987), the FCC embarked on a program of industry deregulation. His successor, Dennis Patrick (1987–1989), accelerated the trend, culminating with the elimination of the Fairness Doctrine.3 That decision put the FCC into bad standing with Congress, which had already been legislating to fill the regulatory void caused by the agency’s policy changes.

After George Herbert Walker Bush became president in 1989, he appointed as FCC chairman Alfred Sikes, former head of the National Telecommunications and Information Administration. Sikes successfully mended congressional fences. He worked to revise certain archaic rules, such as those on financial interest and syndication and, at the same time, pioneered new concepts, like the entry of telephone companies into video. Sikes also undertook some technology-based initiatives, such as high-definition television (HDTV) and digital audio broadcasting (DAB). He was an activist chairman who perpetuated marketplace regulation and charted many new waters. Sikes resigned on January 19, 1993, one day before Bill Clinton assumed office.

President Clinton appointed Commissioner James Quello as acting chairman. He served until Clinton nominee Reed Hundt was sworn in as chairman later that year. Chairman Hundt’s FCC was often bogged down in internal conflict. He did initiate efforts to reintroduce some elements of licensee responsibility in the wake of deregulation. One of his successful undertakings was in the area of children’s television content and reporting rules. Early in President Clinton’s second term, Hundt resigned and was replaced by former FCC General Counsel William Kennard.

In 2001, another Bush, George W., became president. He appointed Michael Powell, son of Secretary of State Colin Powell, as FCC chairman.

He attempted to accelerate media consolidation4 and wrestled with the questions of indecency, violence, and localism. The FCC is a political body and has regular changes in leadership and membership. That is evidenced by Powell’s resignation in 2005 and his replacement by Kevin Martin.

THE ROLE OF BROADCAST REGULATIONS

The FCC, the Broadcaster, and the Public Interest

When broadcasting emerged, it was recognized as having an obligation to serve “the public interest.” This phrase, along with “convenience and necessity,” was included in the Communications Act for specific reasons, not the least of which was to give the FCC maximum latitude to use its own judgment in matters relating to commercial broadcasting. Section 303 of the Communications Act, for example, begins: “Except as otherwise provided in this Act, the Commission from time to time, as public convenience, interest or necessity requires shall.…” This section goes on to list 19 functions, ranging from the power to classify radio stations to the power to make whatever rules and regulations the FCC needs to carry out the provisions of the act. The term “public interest” similarly occurs in the crucially important sections dealing with granting, renewing, and transferring licenses.

The public interest has been discussed and defined by Congress, the courts, broadcasters, and the public for so long that its meaning has become whatever a person wants it to be. This is especially true of broadcasters, since they are ultimately the ones who determine what the public interest means, at least for their audiences. The real burden of definition must come from the FCC, but even the FCC has granted leeway to licensees, since they are in daily contact with their audiences and obtain feedback from them, thereby being able to gauge what is in their best interests. The FCC does believe that it is in the public interest for stations to carry programs dealing with community issues and problems. The whole topic of what is and what is not public interest is once again under review.

Following the Red Lion Supreme Court decision in 19695 upholding the constitutionality of the Fairness Doctrine, many broadcast regulations were based upon the scarcity rationale. It was scarcity that allowed for different First Amendment standards for the print and electronic media businesses. In its 1987 decision eliminating the doctrine, the FCC decided that scarcity of viewpoint sources no longer existed, which left only the concept of public interest as a basis for regulations. In the future, decisions on the public interest would be made on a case-by-case basis.

Other Regulatory Agencies

Broadcast regulation does not come entirely from the FCC. Of all the regulatory agencies, probably the one that has the greatest impact on broadcasting, other than the FCC, is the Federal Trade Commission (FTC).

Deregulation by the FCC has further enhanced the importance of that agency. In 1986, the FCC eliminated many of its rules on station business practices, including fraudulent billing and contests. The terminated regulations were characterized as “unnecessary regulatory underbrush,” which duplicated other federal and state laws. Much of the responsibility abdicated by the FCC was absorbed by the FTC.

The FTC is the federal government’s primary agent for advertising regulation. Its general mandate is to guard against unfair and deceptive advertising in all media. Broadcasters, or rather the companies that advertise on broadcast facilities, are the main targets of this agency, since the broadcast media are a mass-advertising funnel that reaches out to almost the entire population. Because the agency was created under the authority of Congress to regulate interstate commerce, products or services must be sold in interstate commerce, or the advertising medium must be somehow affected by interstate commerce, before the FTC can intervene. Since it is charged with policing unfair or deceptive advertising, the terminology needs to be defined.

Deceptive Advertising

There are four considerations in deciding whether an advertisement is deceptive:

• The meaning of the advertisement must be determined. In other words, what promise is made?

• The truth of the message must be determined.

• When only a part of the advertisement is false, it must be determined whether the false part is a material aspect of the advertisement; that is, is it capable of affecting the purchasing decision of the consumer?

• The level of understanding and experience of the audience to which the advertisement is directed must be determined.6

Two cases will help explain these concepts. In the early 1970s, a spokesman for Chevron F-310 gasoline additive in advertisements claimed he was standing in front of the Standard Oil Research Laboratories when, in fact, he was standing in front of a county courthouse. Was this deceptive advertising? The FTC said no—that the location of a spokesman is irrelevant to a consumer making a purchasing decision.7

On the other hand, Standard Oil of California was ordered to stop claiming that its Chevron gasolines with F-310 produce pollution-free exhaust. The Commission banned television and print advertisements in which the company claimed that just six tankfuls of Chevron will clean up a car’s exhaust to the point that it is almost free of exhaust-emission pollutants.8

Other agencies, both state and federal, also are involved in the regulation of advertising. The advertising industry itself has industry-sponsored groups that are active in resolving complaints against advertisers. The National Advertising Division (NAD) of the Council of Better Business Bureaus is an example.

Consumers, as a whole, have little or no influence when it comes to policing false advertising. For the most part, all they can do is report it to the regulatory agencies.

Besides the FTC, the advertising business is touched by at least 32 federal statutes, including the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act; Consumer Credit Protection Act; Copyright Act; and Consumer Product Safety Act.

The FTC’s ascendancy to fill the regulatory void left by the FCC has not been limited to advertising matters. In a significant decision on FCC mustcarry rules, a federal court adopted an FTC report that concluded that the absence of the rules would not be harmful to local broadcasting.9

Other federal agencies and executive departments have also stepped into the power vacuum left by FCC deregulation actions. One such example is the Department of Justice. It has become especially active since passage of the 1996 Telecommunications Act. As noted above, the act allowed expanded electronic media ownership consolidation nationally and locally. Since then, the department has been investigating on a case-by-case basis the extent to which legally permitted consolidation also concentrates on radio advertising revenue. Such examinations have extended to situations where in-market concentration leads to dominance in a particular format. Transactions subject to review before transfer are said to have been “red flagged.” Still another federal agency stepping into the power vacuum is the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), which is located in the Commerce Department and is the White House policy office on telecommunications. The NTIA is principally a policy agency and its initiatives often show up in the FCC’s agenda.

The Role of FCC Counsel

While it is theoretically possible to navigate the requirements and regulations of the FCC without professional assistance, it is a bad idea. Most electronic media companies opt for qualified legal representation.

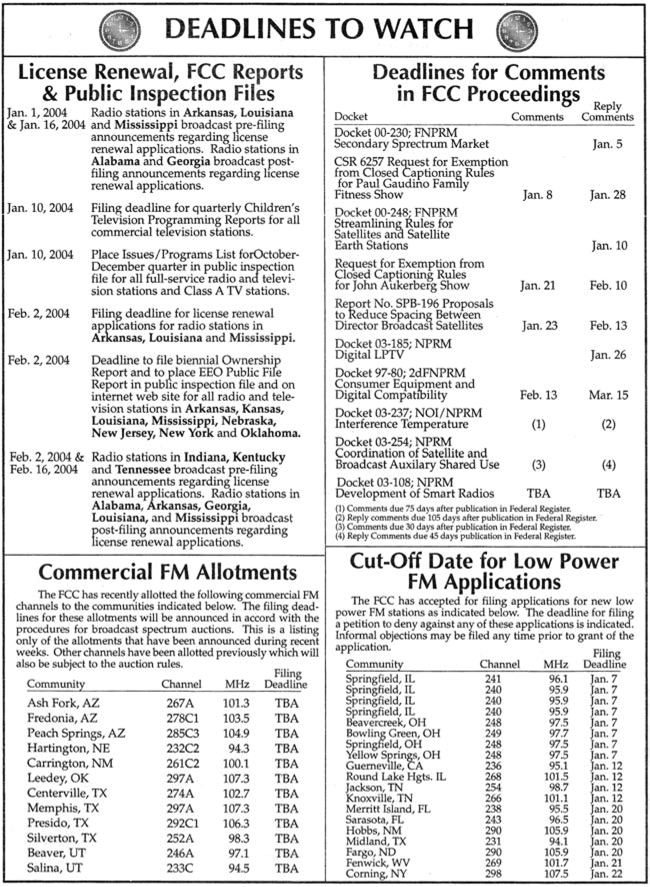

Professional counsel keeps the client abreast of the many FCC deadlines (Figure 7.1) and provides a vehicle for commenting on rules and regulations changes that the FCC is considering. Available FCC firms range from the sole practitioner to the midsize boutique communications specialty firms to the mega worldwide firms.

Figure 7.1 FCC deadlines.

(Source: Drinker Biddle & Reath, LLP. Used with permission.)

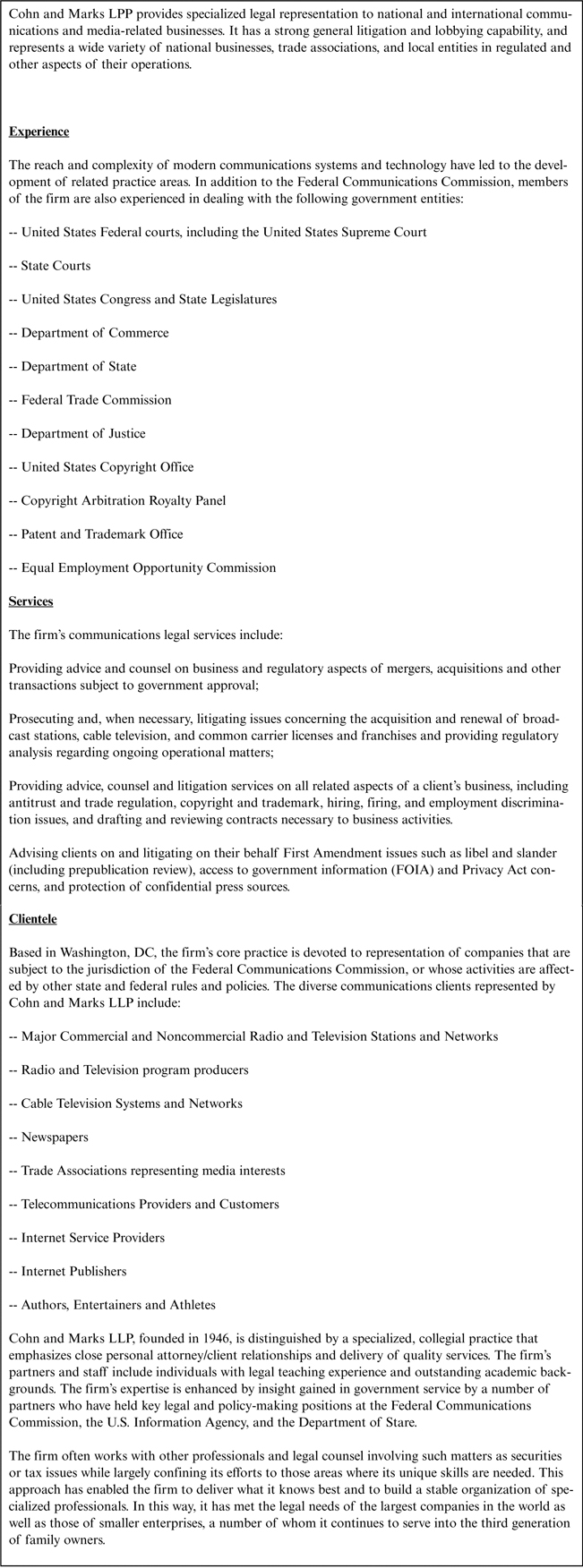

For purposes of illustration, the authors have selected a Washington, DC, boutique firm, Cohn & Marks. This is a smaller specialty firm of about ten attorneys. Figure 7.2 profiles the firm’s experience, services, and illustrative clientele.

Figure 7.2 Profile of the experience, services, and clientele of the Washington, DC, firm Cohn and Marks, LLP.

(Source: Cohn and Marks, LLP. Used with permission.)

APPLICATION AND REPORTING REQUIREMENTS

One day, perhaps, both federal income tax and broadcast station forms will be simplified. Until that happens, the forms will continue to be cumbersome. The broadcast industry is full of forms: for a construction permit to build a radio or television station, for a broadcast license renewal, and so on.

To begin the process of establishing a new broadcast station, an individual, partnership, or corporation must meet certain criteria. They include the following:

• The licensee must be a U.S. citizen.

• The licensee must be of good character.

• The licensee must have substantial financial resources to establish and maintain the station.

• The licensee must have the technical ability to operate the station according to FCC regulations.10

Applicants requesting to construct a new facility or make changes in an existing AM, FM, or TV facility must use FCC Form 301 (Figure 10.13). FCC facility construction permits are issued for a period of three years. They are no longer subject to extension as they once were.

Once the construction is completed, it is necessary to apply for a license using FCC Form 302. Applicants must show compliance with all terms, conditions, and obligations set forth in the original application and construction permit. Upon completion of the construction, the permittee may begin program tests upon sending a notice to the FCC.

During the period of operation, all stations were required to file with the FCC an annual employment report form, FCC 395-B, on or before May 31 of each year. The employment data filed were to reflect figures from any one payroll period in January, February, or March. The same payroll period had to be used each year. The FCC used the reported data to monitor compliance with its equal employement opportunity (EEO) regulations.11

In addition, stations had to file at license renewal time an EEO report form, FCC 396. The report was required to determine whether or not the station’s personnel composition reflected that of the community of license. Stations with fewer than five employees were exempt from filing the form.

In 1998, the FCC suspended the requirement that stations file the two forms in the wake of a court ruling that threw out the FCC’s broadcast affirmative action requirements.12 Chairman Kennard announced that a proposal for new rules would be issued, and he urged broadcasters to voluntarily file EEO data with the FCC. Subsequently, the FCC adopted a new EEO plan. A detailed discussion of the commission’s EEO reporting regulations appears in Chapter 3, “Human Resource Management.”

The FCC requires each commercial broadcast licensee to file an ownership report, FCC Form 323, once a year, on the anniversary of the date that its renewal application must be filed.

Sports and network affiliation agreements must be in writing, and single copies of all local, regional, and national network agreements must be filed with the FCC within 30 days of execution.

Deregulation has ended the need to file with the FCC notification of radio and television station programming changes. To replace previous program ascertainment requirements, the FCC requires only that stations place in their public file quarterly a list of five issues and programming related to those issues. The quarterly lists must be in the file by January 10, April 10, July 10, and October 10, respectively, each year. See Figure 7.3 for an illustration of what a typical station quarterly issues/programs list might look like. Note that the list should reflect the station’s “most significant programming treatment” of community issues and needs. The programming need not be locally produced.

Figure 7.3 Sample quarterly issues/programs list.

(Source: Cohn and Marks, LLP. Used with permission.)

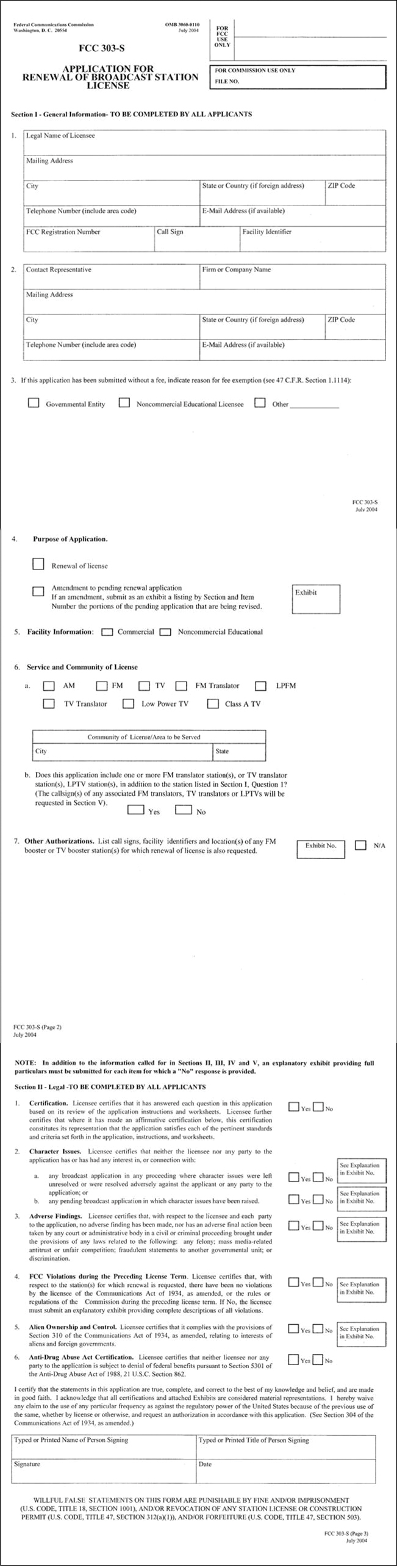

Broadcast licenses are not issued on a permanent basis and must be renewed on a regular timetable. All licensees, except those TV and noncommercial stations selected to complete the long-form audit, must file the simplified renewal application form, FCC 303-S (Figure 7.4). It must be filed every eight years by television and radio stations, on or before the first business day of the fourth month prior to the expiration of the existing license.13

Figure 7.4 Excerpt from FCC Form 303-S.

The short-form renewal was a product of deregulation and consisted of only eight questions. However, the simplicity has begun to fade, and the “postcard” form has grown from its original 1 page to 29 pages. In response to the Children’s Television Act of 1990,14 the FCC added a ninth question for all television renewal applicants. It requires a summary of the applicant’s children’s programming activity and its compliance with commercial content restrictions. Other questions have been added since then.

Licenses that are in good standing may be sold and transferred by licensees to third parties with the consent of the FCC. To obtain consent, the seller and buyer must file with the FCC’s Media Bureau FCC Form 314 (see Figure 10.11).

OWNERSHIP POLICIES

Simply put, the ownership rules govern who can own what, and where. They include limitations on numbers and kinds of stations that can be commonly owned in a market and on the total number that can be owned in the country as a whole by a single person or entity.

Another ownership consideration has to do with the length of time a station must be held by an owner before it can be sold. Cross-ownership rules exist for newspaper-broadcast combinations.

Deregulation’s largest impact on changing the face of the broadcast industry has resulted from the relaxation of the ownership rules. The oldest and best known was the duopoly rule, which was designed to prevent a single person or entity from owning more than one station in a market providing the same class of service. Consequently, no individual or company could own more than one AM, one FM, or one TV station in the same service area. This media-concentration rule served its purpose for many years. But the decline of AM’s competitive position in particular, and of radio’s profitability in general, led to its reexamination.

The Progression to Consolidation, 1992–1996

On September 16, 1992, a new duopoly rule became effective. The change allowed a single party to have up to three radio stations in the same market in markets with fewer than 15 stations. However, the three commonly owned stations could not exceed 50 percent of the total number of stations in the market. No more than two of the three stations could be the same class of service (AM or FM). In markets with 15 or more stations, a single entity could own up to four stations, no more than two of which could be AM or FM. In those markets, there was an additional requirement: the combined audience share of the commonly owned stations could not exceed 25 percent.

Before the implementation of the new local ownership rules, many operators who were experiencing financial or competitive strain had entered into local marketing agreements (LMAs). Under an LMA, a station sells all or some of its weekly broadcast schedule to another station in the market, which uses the air time to broadcast content, including commercials, over the selling station. When the new duopoly regulations were adopted, they were accompanied by a new LMA requirement. It said that if an LMA exceeded 15 percent of the selling station’s weekly broadcast schedule, that station had to be counted as an owned station for the station buying the time. For example, if FM station A bought more than 15 percent of the time of FM station B, FM station A could own no other FM station in the market because two was the limit in the same class of service.

The ownership rule changes also affected the limits for the number of stations that could be owned nationwide by a single party. The 1992 multiple ownership rules increased the radio levels to 18 AM and 18 FM stations, and a further increase to 20 AM and 20 FM stations was permitted thereafter.

The television multiple-ownership limit of 12 was unaffected by the 1992 changes. However, the television rule depended upon the percentage of TV households reached nationally by commonly owned stations, with the upper limit being 25 percent. Therefore, if a company owned five television stations that covered 25 percent of the television households in the United States, it could not own any more. Special variations of the rule allowed UHF stations to count for only one-half of television market households in calculating the 25 percent.

The 1996 Telecom Act: Consolidation Accelerated

The change in local ownership rules continued in the 1996 Telecommunications Act. Now, the changes became dramatic.

Multiple ownership limits for radio nationwide were eliminated completely. By 1998, there were publicly traded companies that owned hundreds of commercial radio stations each. Such companies included Clear Channel, Cumulus, and Infinity.

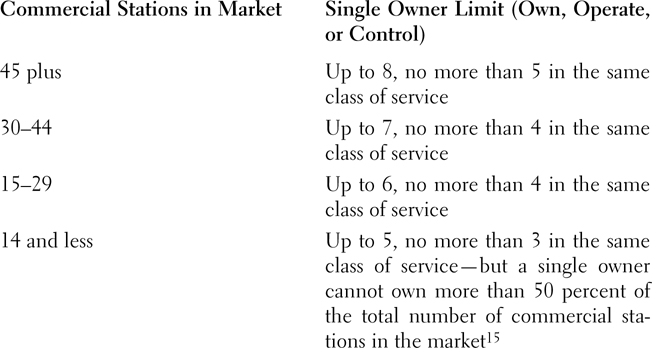

The local-level ownership rules for radio changed as well. Limits were set according to market size and class of service. The 1996 local radio ownership concentration rules are as follows:

The television rules were changed more modestly under the 1996 act. National ownership levels were removed, as they were in radio. However, there was a cap of coverage of 35 percent of U.S. TV households. Once that limit was reached, no additional stations could be purchased, whatever the number of stations currently owned.

The 1996 law permitted the FCC to issue waivers to allow common ownership of radio and television stations in the same market. The prohibition on duopoly ownership of TV stations in the same market remained, but the 1996 law ordered the FCC to study the matter. Existing restrictions against daily newspaper ownership of electronic media servicing all or part of the same market continued, but were under FCC review.

Prior to the 1996 law, the FCC eliminated what was known as the “three-year rule.” It had required broadcasters who acquired a station to operate it for three years before being allowed to sell it. Now, there is no holding period for existing stations. The end of the rule led to a flurry of station transactions and brought new investors and new types of financing into the industry.

The combination of the changes in the ownership rules and the abolition of the three-year rule resulted in innumerable mergers, corporate takeovers, and leveraged buyouts.

Ownership Rules Changes Post-1996

The 1996 law mandated that the FCC conduct an ownership rule review every two years. The purpose was to ascertain if the rules were still necessary in the public interest as a result of competition.16

One such review resulted in FCC adoption of new rules on media concentration in June 2003.17 The proposed new rules allowed ownership of more than one TV station in a market depending on the number of TV stations in the market. For example, a company could own two stations in a market with five or more stations.

The national limits on TV station ownership were increased from a household penetration of 35 percent to a maximum of 45 percent. However, in January 2004, Congress reduced the national level to stations that reach 39 percent of total TV households. The new rules maintained the “UHF discount.”

The local radio limits remained the same as set in the 1996 Telecomm Act, but the FCC replaced its signal contour method of defining radio markets with a geographic market approach designed by Arbitron. The national limit on radio station ownership remained unlimited.

Cross-ownership was permitted among TV, radio, and newspapers. The FCC restated its commitment to localism.

The new rules were challenged immediately in the federal courts and stayed. In June 2004, the rules were sent back to the FCC by a federal court of appeals for reexamination. The stay against implementing the rules continued.

The FCC petitioned the court for a rehearing on that portion of its ruling pertaining to media ownership. The June 2003 proposed ownership rules were adopted on a 3-2 party-line vote. Commissioners and chairpersons often change in the wake of a presidential election, even if the ruling party remains in office. For that reason, the future of the 2003 rules changes now on remand to the FCC is not certain. However, in September 2004, the court did allow the FCC to implement the rule that the number of stations permitted in a market would be based on the Arbitron definition of a market.

Localism

The proposed ownership rule changes in June 2003 resulted in an FCC examination into whether or not the ownership concentration triggered by the 1996 act had diminished the dedication to localism.

In September 2003, Chairman Powell announced a localism initiative.18 It had three parts: (1) a localism task force; (2) accelerating activation of lowpower stations; and (3) notice of inquiry.19

Powell appointed a localism task force that conducted hearings around the country. Further, the FCC opened a filing window to resolve conflicts among low-power FM applicants. The commission believes that LPFM epitomizes local broadcasting. Finally, the FCC issued a notice of inquiry to collect comments on whether localism-based rules are effective or need to be changed or supplemented.

PROGRAMMING POLICIES

Programming policies cover a broad area of station activity. Here, the focus is on those of particular significance to station management.

Political Broadcasts

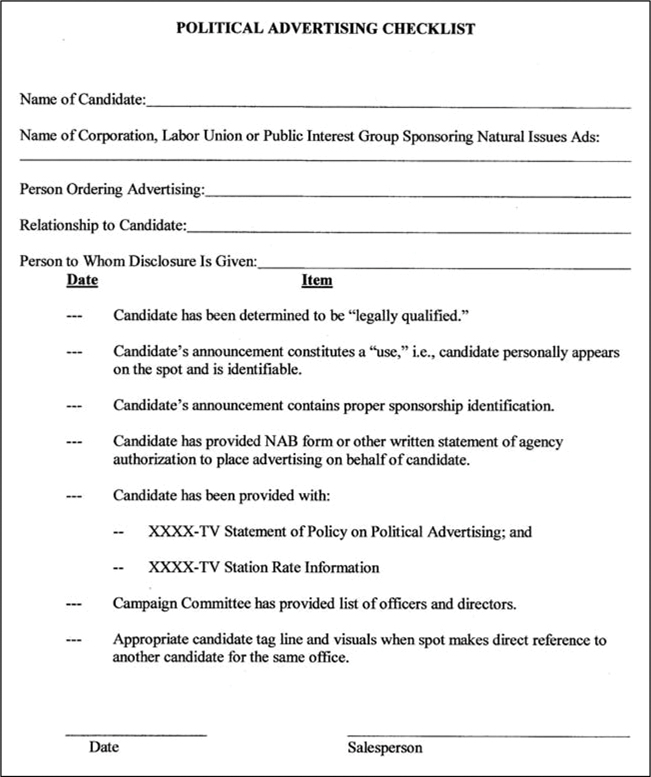

Enforcement of federal laws and FCC regulations pertaining to political advertising has become a particular emphasis with the FCC. There is obviously a great deal of interest in this topic by office holders and office seekers. Congressional pressure has led to political rate audits, and the FCC is authorized to levy fines for violations of the political rules. Former candidates have also sued broadcast stations for alleged overcharges. Who is allowed access to the airwaves, when, and at what rate are critical questions. Ignorance or informed noncompliance can be expensive and career-ending. FCC attorneys advise their clients to issue political advertising policy statements and to maintain a station political advertising checklist (Figure 7.5). Now, on to the specifics of the laws and regulations.

Figure 7.5 Sample political advertising checklist.

(Source: Cohn and Marks, LLP. Used with permission.)

The “equal opportunities” provision of Section 315 of the Communications Act is commonly (and incorrectly) referred to as the “equal time” provision. It allows broadcasters to permit a legally qualified candidate for public office to “use” a station’s facilities, but they must afford equal opportunities to all other opposing legally qualified candidates for that office, provided a request for equal opportunities is made within seven days of the first prior use.

The use of a broadcast facility by a candidate is defined as any appearance on the air by a legally qualified candidate for public office, where the candidate either is identified or is readily identifiable by the listening or viewing audience. Appearances by candidates in the following types of broadcasts are not considered “uses” and are exempt from the provision:

• bona-fide newscasts

• bona-fide news interviews

• bona-fide news documentaries (if the appearance of the candidate is incidental to the presentation of the subject or subjects covered by the news documentary)

• on-the-spot coverage of bona-fide news events (including but not limited to political conventions and activities incidental thereto)

In response to petitions from the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) and others, the FCC authorized broadcasters to sponsor political debates. In 1987, the debate exemption was expanded to cover candidate-sponsored debates.20 In both cases, even if all competing candidates do not appear in the debate, the broadcast will be exempt from the equal opportunities requirements, provided the debate has genuine news value and is not used to advance the candidacy of any particular individual. Also, taped debates need not be aired within 24 hours of their occurrence to qualify for exemptions, as long as they are broadcast currently enough so that they are still bona-fide news.

Specifically, licensees now may air in-studio debates featuring only the most significant candidates. Minor candidates are not entitled to request other air time if they are not invited to appear.

In 1991, the Section 315(a) (4) exemption was expanded to include a situation in which a local television station dedicated an hour of time to be shared equally by the two major presidential candidates for separate 30-minute presentations. Although not technically a debate, it did qualify for the use exclusion.21

If a broadcast constitutes a “use” of a station by a legally qualified candidate for public office, Section 315 of the Communications Act prohibits a station from censoring the broadcast content, directly or indirectly. This “no censorship” provision bans a station from refusing to broadcast a “use” by a candidate or any person connected with the content or format of the broadcast. Thus, even if the proposed broadcast contains libelous statements, the station is prohibited from rejecting it. For this reason, the U.S. Supreme Court has exempted broadcasters from liability under state libel and slander laws for any defamatory material contained in such a broadcast use.

Under Section 312(a)(7) of the Communications Act, broadcasters are required to allow “reasonable access to or to permit purchase of reasonable amounts of time for the use of a broadcasting station by a legally qualified candidate for Federal elective office on behalf of his candidacy.” In 1971, the FCC ruled that each licensee has a public interest obligation to make the facilities of its station “effectively available” to all candidates for public office. It was assumed that this rule would be considered in a case-by-case manner.

Comparisons between the requirements of Sections 315 and 312(a)(7) always seem to cause confusion. It can best be avoided by remembering that, under Section 315, a broadcaster has no obligation to political candidates unless one of them has been allowed to use the broadcast facility. Section 312(a)(7), on the other hand, requires a broadcaster to provide time to candidates for federal elective office. Section 315(b)(1) and (2) of the 1934 act set standards for rates to be charged to political candidates. The following paragraphs summarize the rate advice one law firm provides to its clients:

For “uses” broadcast during the forty-five days before a primary or primary runoff election and sixty days before a general election (including election day), you may charge candidates no more than your “lowest unit charge” for the same class (rate category) of advertisement, the same length of spot, and the same time period (daypart or program). The candidate must be sold spots at the lowest charge you give to your most favored advertiser for the same class, length of spot and time period. If your lowest unit charge is commissionable to an agency, you must sell to candidates who buy direct at a rate equal to what the station would net from the agency buy. This agency rule does not apply to spots sold by a station’s national rep firm.

Candidates get the benefit of any volume discounts you offer to other advertisers even if they purchase only one spot. Thus, if you charge $20 for a single one-minute spot and $150 for ten one-minute advertisements (or $15 per ad), you may charge a candidate only $15 for a one-minute ad even if the candidate buys only one spot. However, you can offer legally qualified candidates an additional volume discount from the lowest unit charge for purchases that do not qualify for the volume discount, but you must make the volume discount available on a non-discriminatory basis to all candidates.

Any station practices that enhance the value of advertising spots must be disclosed, and must be made available to candidates. These include, but are not limited to, discount privileges that affect the value of the advertising, such as bonus spots, time-sensitive make goods, preemption priorities, and other factors that enhance the value of the advertisement. Under the rules, if you have provided any commercial advertiser with even a single time-sensitive make-good for the same class of spot during the preceding year, you must provide time-sensitive make goods for all candidates before the election.

Only “uses” by legally qualified candidates for public office are entitled to the lowest unit charge. The candidate must appear personally in the spot by voice or image, and the appearance must be in connection with his or her campaign. If the owner of the general store runs for sheriff, he or she is not entitled to the lowest unit charge for spots promoting the store’s weekly specials.

A demand for equal opportunities can change this. A candidate making a valid equal opportunity claim in response to his or her competitor’s spots will be entitled to the same rate the competitor paid, and may use the time any way he or she sees fit. If the candidate he or she is responding to got the lowest unit charge, he or she gets it too, by operation of the equal opportunities provision.22

In addition to all the other requirements, broadcasters have an affirmative obligation to discover who is behind the nominal sponsoring organization of political advertising.

All of these matters, including “issues” advertisements, are now subject to Congressional and Department of Justice examination.

Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 (BCRA)

This law, also known as the Campaign Spending Law, amended Section 315 of the 1934 Communications Act.

As noted earlier, candidates for federal elective office receive the lowest unit rate 45 days before a primary or 60 days before a general election. BCRA requires that federal candidates must do something additional to qualify for the lowest unit rate. At the time of purchase of lowest unit rate spots, the candidate or the authorized committee must certify in writing that the candidate will not make any direct reference to another candidate for the same office unless the political spot contains, for radio, a personal audio statement voiced by the candidate and identifying the candidate and the office being sought and announcing that the candidate has approved the broadcast.

For television and cable, a clearly identifiable photograph or similar image of the candidate must be shown for at least four seconds and a simultaneously displayed printed statement must identify the candidate and advise that the candidate approved the broadcast and that the candidate or the candidate’s authorized committee paid for the broadcast.

BCRA was to be the law that outlawed the unregulated and unrestricted use of soft money. It was to be replaced by third-party issue ads. Third-party issue ad organizations are called 527s. In the 2004 presidential campaign, such organizations generated much controversy.

As to third-party issue ads (i.e., political ads that advocate the election or defeat of federal candidates or solicit any political contributions, but are not authorized by a federal candidate or the candidate’s authorized campaign committee), the ad must state that it is not authorized by any federal candidate and identify the name of the responsible political party, committee, person and/or connected organization paying for the broadcast. For television and cable, this statement is required to be made with an unobscured, full-screen view of a representative of such committee or other person in voice-over. It must also appear for at least four seconds in a clearly readable manner with a reasonable degree of contrast between the background and the printed statement. Surely, you have seen or heard these announcements. Now, you know why.

BCRA also imposed some new public file requirements. They are set out later in the chapter.

Fairness Doctrine

The Fairness Doctrine required broadcasters to devote time to coverage of “controversial issues of public importance” and to make sure that such coverage was not grossly out of balance. In other words, reasonable opportunity was to be afforded for presentation of contrasting views. It was left to broadcasters to decide what issues were controversial and how to treat them on the air.

After calling the Fairness Doctrine the sine qua non for broadcast license renewal in 1974, the FCC declared it unconstitutional and essentially unenforceable in 1987.23 Subsequent to its repeal, Congress each session, until 1993, annually passed a law to codify the doctrine. Since the Republicans took over Congress in 1995, there has been no such effort and the FCC has shown little interest.

In 2000, the FCC repealed its personal attack and political editorial rules, both corollaries of the Fairness Doctrine. That action would seem to have sealed its fate.

However, the FCC’s media ownership rules may give it life again. The objections to the perceived loss of localism as a consequence of ownership concentration in local markets may revive the doctrine’s corpse. Localism is intertwined inextricably with Fairness Doctrine concerns.

Children’s Programming

The FCC began a study of children’s television programming in the early 1970s. In 1974, it issued a Children’s Television Report and Policy Statement. The Commission stated that television stations would be expected to provide diversified programming designed to meet the varied needs and interests of the child audience. It said that television stations should provide a “reasonable amount” of programming designed for children, intended to educate and inform, not simply to entertain.

On December 22, 1983, the FCC adopted a report and order terminating its 13-year inquiry into this kind of programming. While reaffirming the obligations of all commercial broadcast television stations to serve the special needs of children, it rejected the option of mandatory programming requirements for children’s television by a three-to-one vote. As a result, broadcasters could justify their inattention to such programming based on alternate children’s programming available in the market on public television or cable.

Citizens’ groups were outraged by the perceived FCC abandonment of the licensee’s obligation to children’s programming. Their unhappiness was intensified by the FCC’s 1984 elimination of commercial guidelines for children’s programming.

In 1990, activists succeeded in their efforts to restore commercial limits and licensee program obligations for children, and the Children’s Television Act passed. President Bush (the elder) signed the law and, in 1991, the FCC adopted regulations implementing the act. They went into effect in 1992.24

As administered by the FCC, the act no longer allows broadcasters to satisfy their children’s programming obligation by relying on what is available on cable and public television. Children’s programming was defined as those “programs originally produced and broadcast primarily for an audience of 12 years old and under.”25 Broadcasters’ compliance with the program requirements would be examined at license renewal time. The law also reimposed limitations on commercials in children’s programming: 12 minutes per hour on weekdays and 10.5 minutes on weekends.

Under regulations adopted by the FCC to implement the 1992 law, television stations had to report quarterly in their public inspection file their compliance with the commercial limits requirements. In addition, TV stations were to keep an annual list of programming and other efforts geared to meet the educational and informational needs of children.

FCC experience under the new regulations was not good. Fines for exceeding the commercial limits were sizable and frequent. The anticipated children’s programming upgrade and improvement did not occur.

After four years of experimentation under the Children’s Television Act, the FCC in 1996 issued new rules and new reporting requirements. The Telecommunications Act required TV stations to air at least three hours per week of “core” children’s programming, which is defined as programming designed to educate and inform children. It must air on a regularly scheduled basis weekly during the hours of 7:00 A.M. to 10:00 P.M. Such programming must be at least 30 minutes in length.

To monitor compliance with its new rules, the FCC also introduced FCC Form 398, which television stations must complete on a quarterly and annual basis. It requires the reporting television station to have a named children’s programming liaison and to report performance for the quarter just ended and plans for the quarter coming up. The station must also notify the public of the existence of Form 398 and collect public comments on its children’s programming.

Obscenity, Indecency, and Profanity

The U.S. Criminal Code forbids the utterance of “any obscene, indecent, or profane language by means of radio communication.”26 The problem, as it pertains to programming, is the definition of what is obscene or indecent.

The prevailing standard for obscenity was adopted by the U.S. Supreme Court in its 1973 resolution of Miller v. California. The Court’s three-part test is: (1) whether the average person, applying contemporary community standards, would find that the work, taken as a whole, appeals to prurient interests; (2) whether the work depicts or describes in a patently offensive way sexual conduct specifically defined by applicable state law; and (3) whether the work lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.

After the Miller case, the FCC standard for indecency was the “seven dirty words” test announced in the Pacifica case involving George Carlin.27 That changed in 1987, when the FCC issued a new indecency standard.28 It is now defined as “language or material that depicts or describes, in terms patently offensive as measured by contemporary community standards for the broadcast medium, sexual or excretory activities or organs.” Contemporary community standards, said the FCC, were meant to be those of the average broadcast viewer or listener.

The 1987 indecency standard has been a problem from its inception. There have been three major points of contention: What was prohibited? When was it prohibited? How much would violations cost? The standard itself has been upheld by court decisions in the face of claims that it is vague and indefinite.29

Enforcement hours have been another story. Originally, the FCC proposed a “safe harbor” when adult programming might be broadcast. That time period was identified as the hours of midnight to 6:00 A.M. For a time, under a congressional mandate, the FCC extended the coverage of its indecency rule to 24 hours a day. However, the courts repeatedly refused to allow the FCC limitations. The issue was finally resolved in 1995 when the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit ruled that the FCC could permit the broadcasting of indecent material between the hours of 10:00 P.M. and 6:00 A.M. 30

In addition to establishing safe harbor hours for adult content, the FCC, as noted in Chapter 4, “Broadcast Programming,” has approved a voluntary ratings system to alert viewers to adult content, indecency, and violence in television programming.

Another major enforcement wrinkle is the amount of an FCC fine. Under current forfeiture schedules, the basic one-time indecency fine is $7,000, with statutory discretion based on circumstances to raise that to a maximum of $27,500. In June 2004, the FCC adjusted its maximum forfeiture penalties to reflect inflation. The new rates for indecency are $32,500 per violation or per day of a continuing violation with the amount of continuing violation not to exceed $325,000.31 Many of the cash penalties imposed so far have been against New York “shock jock” Howard Stern. His show is syndicated nationally, and the FCC has been fining both the originating and carrying stations.

Clear Channel Communications carried Stern in six markets and it was fined $175,000 by the FCC in 2004.32 The company agreed to the fine and told Congress it was cleaning up its act. “Zero tolerance” is the term it uses to describe its indecency policy.33 Major broadcasting companies are trying to pass through indecency fines to talent. In some instances, talent has been fired and, like Stern, may be heading for the unregulated satellite skies.34

The frenzy over indecency was triggered by a television show and not a radio show. In February 2004, singer Janet Jackson had an on-the-air “wardrobe malfunction” during the Super Bowl halftime show with Justin Timberlake.35 In September 2004, the FCC fined CBS, the offending network, $550,000 for the incident.

Consequently, congressmen and senators outdid each other in their zeal to raise the indecency fine.36 So as not to miss the boat, the FCC began consideration of a requirement that broadcasters record and archive their programs for possible indecency compliance issues.37

Indecency has been, and will be, a major initiative for the FCC. Litigation is costly, and broadcasters who cannot afford to fight for perceived First Amendment principles would be well advised to be cautious in observing a less-than-definite standard. The only real definition we had from the FCC on indecency pertains to the “F word.” It is bad, anywhere and anytime,38 even at the 2004 Democratic National Convention on CNN.39

Violence

Violence is, and has been, an area of industry self-regulation. While threatening regulation, the FCC knows very well, given its problems with indecency, that program content regulations are difficult to enforce. From time to time, members of Congress, like the late Senator Paul Simon, have threatened legislation. However, each time the industry has escaped.

One serious threat was resolved when the FCC adopted a table of voluntary program ratings (see Appendix A, “TV Parental Guidelines”) designed to alert viewers to program content. Compliance with the ratings by program exhibitors has not been universal.

In addition to the ratings initiative, there was also an agreement by the television networks to pay for an ongoing independent study of the level of violence in television programming. The agreement followed threats of FCC regulation and congressional legislation.

However, the wolf is at the door again. A motivated FCC, in the company of some powerful U.S. senators, has opened a new notice of inquiry into violent programming. Part of this incentive comes from the 2004 indecency frenzy. There has been an effort in Congress to exile violent programming to the safe harbor established for indecency.40 Time will tell.

Racial Slurs

Shock jocks are not new to the airwaves, but the audience fragmentation of the 1990s and the success of Howard Stern have led to a shock jock breakout from East to West. More and more on-air hosts are pushing the envelope of acceptable standards for program content. Complaints about problem content are no longer limited to indecency. The 1990s saw an increasing number of allegations of racism.41

The FCC has been confronted with the problem of racial comments in the past. Its policy has been to rely on industry self-regulation, and it has no fine or forfeiture for such comments. The FCC’s position is that federal law does not prohibit them. Indeed, the U.S. Supreme Court has decided that hate speech is protected First Amendment activity.42

In one case, the FCC was asked to halt the sale of a Washington, DC, radio station to a company that employed a disc jockey who allegedly made racially insensitive comments on the air. In a petition filed to block the sale, the African-American Business Association said that the sale would create a hostile environment for Blacks working at the station.43

While a search is under way to find a solution to this emerging problem at the national level, the current remedial approach appears to rely on the amount of pressure that can be brought against management by community groups. In one instance, community pressure was joined by a withdrawal of advertising support for the offending program, and station management elected to suspend and then fire the disc jockeys.44 In 1998, five years after their dismissal, the disc jockeys were hosting a successful nationally syndicated morning show in the same market. Where dictates of good taste do not govern an air host’s behavior, perhaps concern about occupational longevity would be an appropriate guiding principle. But, obviously, it does not always work.

On-the-Air Hoaxes

The electronic media industry has a legacy of spoofs and hoaxes dating back to the famous 1938 “War of the Worlds” broadcast by Orson Welles. His elaborate radio production describing an invasion from Mars caused a panic.

The late 1980s and early 1990s saw a new rash of incidents, perhaps another by-product of audience fragmentation. One, in St. Louis, resulted in a substantial FCC fine. In that case, a disc jockey for KSHE-FM aired a Civil Defense alert for impending nuclear attack.45 The fact that it occurred in the midst of the Gulf War only intensified audience reaction.

Responding to this and other complaints, many involving false reports of crimes, the FCC issued a new hoax rule in 1992. It forbids the broadcast of false information concerning a crime or catastrophe if (1) the information is known to be false; (2) it is foreseeable that the broadcast will cause substantial public harm; and (3) broadcast of the information does, in fact, directly cause substantial harm.46 The basic FCC one-time fine for knowingly broadcasting a hoax is $7,000.

Lotteries

There has been a long-time FCC requirement that prohibits stations from broadcasting any advertisement or information concerning a lottery. As noted in Chapter 6, “Broadcast Promotion and Marketing,” there are three elements to a lottery: prize, chance, and consideration. The prize must consist of something of value. Chance means that skill will not improve a player’s chance of winning. Consideration means that the contestant has to provide something of value to participate. Listen- or watch-to-win requirements by many stations are not deemed to be consideration.

Many states have lotteries that use the electronic media to promote and disseminate information, but there was some concern that the FCC lottery prohibition would prevent broadcasters from airing lottery spots and news. To remedy the situation, Congress passed a law stating that the lottery rule should not apply to “an advertisement, list of prizes, or information concerning a lottery conducted by a state … broadcast by a … station licensed to a location in that state or adjacent state which has a lottery.”47

Congress revisited the lottery question in 1988 when it passed the Charity Games Advertising and Clarification Act. The FCC implemented the law in 1990.48 In essence, the new rules created further exemptions to the general lottery prohibition. Basically, lotteries for tax-exempt charities, governmental organizations, and commercial establishments running an occasional lottery may be advertised now. To qualify, however, the lottery and its advertising must be legal under state law.

The FCC does have a fine for noncompliance with the lottery rule: $4,000 per occurrence. This is one area in which broadcasters may need local legal advice before proceeding.

In recent years, questions have arisen about the ability of broadcasters to carry commercials for casinos that have sprung up around the country. Initially, the FCC reasoned that, under the lottery prohibition of the United States Code,49 they could not. There has been a series of cases on the topic and, in 1998, the Supreme Court refused to review a decision of the Ninth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals that found the FCC’s gambling prohibition unconstitutional.50

The FCC has said that it will enforce its gambling casino advertising prohibition in those states not affected by the decision, absent a court order. Apparently, gambling advertising will be legally contested state-by-state.

Other Regulations

The deregulation era has seen the termination of many regulations, some of long standing. Most were eliminated in the FCC’s “regulatory underbrush” proceedings in the 1980s, which allowed other federal agencies, like the FTC, to enter the regulatory void. Among the FCC regulations discontinued were those pertaining to

• double billing

• distortion of audience ratings

• distortion of signal coverage maps

• network clipping

• false, misleading, or deceptive advertising

• promotion of nonbroadcast business of a station51

Obviously, many rules remain in effect. Two that bear mention are rules regarding contests and phone conversations. The FCC has a strict contest rule.52 As noted in Chapter 6, “Broadcast Promotion and Marketing,” it requires the following:

• A station must fully and accurately disclose the material terms of the contest (prizes, eligibility, entry terms, etc.).

• The contest must be conducted substantially as advertised.

• Material terms of the contest may not be false, misleading, or deceptive.

As applied by the FCC, failure to mention a relevant fact can be as serious as making a false statement. For example, advertising a resort stay as a contest prize must include information that transportation is not included, if it is not.

FCC phone conversation rules also survived the “underbrush” proceedings. Simply stated, persons answering the phone must grant permission before their voice is put on the air live or prior to recording it for later broadcast.

ANNOUNCEMENTS

As used in broadcasting, the word “announcement” has a multitude of meanings and just as many regulations to cover them.

If a broadcast station or network airs a program that relates to an element of time that is significant, or if an effort is made by the program content to create the impression it is live, an announcement must be made stating that the program is either taped, filmed, or recorded.

A good example might be ABC-TV’s “The Day After,” which dealt with the time in which we live and the fear of World War III and a nuclear holocaust. The program was done in such a way that it seemed that the action was taking place live. The producers included messages at the beginning and end of the program that it was a taped dramatization.

Broadcast stations are required to identify themselves at the beginning of daily operations and at the end of operations for that day. In other words, stations must start and end their broadcast day with station identification announcements. They are also required to air a station identification hourly, as close to the hour as feasible at a natural break in the programming. Television stations may make their station identifications either visually or aurally.

When a station broadcasts any material for which it receives compensation, it must identify the person or group sponsoring the broadcast. Compensation refers to money, services, or other valuable consideration. Sponsorship identification remains a problem, particularly in children’s shows where the station receives the program from a distributor in exchange for air time.

Disregarding the sponsorship identification rule has landed some stations in trouble for payola, the practice whereby recording company representatives have secretly rewarded disc jockeys for playing and plugging certain records. Payola is one FCC policy that has not been a casualty of deregulation.

Similarly, the sponsorship identification rule also applies to plugola. That is the on-the-air promotion of goods or services in which someone selecting the material broadcast has an undisclosed financial interest.

In broadcasting, there is a type of announcement referred to as a “teaser” or “come-on” spot. This announcement may consist of catchwords, slogans, symbols, and so forth. The intent is to arouse the curiosity of the public as to the identity of the advertiser or product to be revealed in subsequent announcements. The FCC has ruled that, even though the final advertisement in a campaign fully identifies the sponsor, the law requires that each teaser announcement reveal the identity of the sponsor.

When concert promotions are carried on a station and it receives some type of valuable consideration in return, the station must make this fact known. Concert-promotion television announcements for which consideration has been received must be logged as commercial announcements.

Finally, there are public service announcements. These are announcements aired by the station without charge and include spots that promote programs, activities, or services of federal, state, or local governments (e.g., sales of savings bonds), or the programs, activities, or services of nonprofit organizations (e.g., Red Cross, United Way), or any other announcements regarded as servicing community interests. Here, the station must identify the group on whose behalf the PSA is being aired.

COMMERCIAL POLICIES

Commercial broadcasting in the United States operates in a free-enterprise system. Profit is the motivating factor, and it comes from a station’s success in generating revenue from advertisers.

The public interest should be the primary consideration in program selection. However, as part of the deregulation of radio and television, the FCC has eliminated all program-length commercial restrictions. The rationale is the belief that audience selection and other marketplace forces will be more effective in determining advertising policies that best serve the public.

On the other hand, the FCC continues to prohibit the intermixture of commercial and programming matter. Its basic concern is whether a licensee has subordinated programming in the public interest to commercial programming, in the interest of salability. The selection of program matter that appears designed primarily to promote the product of the sponsor, rather than to serve the public, will raise serious questions as to the licensee’s purpose. But the fact that a commercial entity sponsors a program that includes content related to the sponsor’s products does not, in and of itself, make a program entirely commercial.

If the program content promotes an advertiser’s product or service, one key question the FCC will ask is on what basis the program material was selected. If the licensee reviews a proposed program in advance and makes a good-faith determination that the broadcast of the program will serve the public interest and that its information or entertainment value is not incidental to the promotion of an advertiser’s product or service, the program will not be viewed as a program-length commercial. To avoid any possible questions by the FCC, care should be taken to separate completely the program’s content and the sponsor’s sales messages.

Another commercial policy deals with “subliminal perception.” Briefly, this pertains to the practice of flashing on a television screen a statement so quickly that it does not register with the viewer at a conscious level, but does make an imprint on the subconscious. For instance, if a station or network were to flash on the screen the words “Buy Coke” every ten seconds throughout a program, in all probability the viewer would have a strong desire to buy a Coke by the end of the program. It is quite obvious why this type of advertising is illegal.

For years, radio and television broadcasters have been accused of “cranking up the gain,” so to speak, on their commercials. Whether the commercials are louder than the program itself has to be determined on an individual basis. The FCC requires that stations take appropriate measures to eliminate the broadcast of objectionably loud commercials.

The sale of commercial time is the lifeblood of the broadcasting industry. However, there may be times when a licensee does not want to sell time to an individual or group. The courts have held that broadcast stations are not common carriers and may refuse time for products or services they find objectionable. The licensee also may refuse to do business with anyone whose credit is bad.

Whether stations should be required to sell time for opinion or editorial advertising was an open question until 1973, when the Supreme Court upheld the principle of licensee discretion. Care should be taken to note the exceptions to the general rule. First, it is obvious that stations cannot refuse to sell time to a political candidate in response to a valid Section 315 equal opportunities request. Second, the antitrust laws make it illegal for a station to refuse advertising if the purpose of the refusal is to monopolize trade or if the refusal is part of a conspiracy to restrain trade.

Prior to the FCC’s “postcard renewal” and deregulation proceedings, license renewal applicants were required to state the maximum amount of commercial matter they proposed to allow in any 60-minute period. Currently, there is no rule that limits the amount of commercial material that may be broadcast in a given period of time.

Restrictions placed on commercials in children’s programs included commercial limits, separation of program and commercial matter, excessive promotion of brand names, and false advertising. The FCC had eliminated commercial limits in its deregulation of television, but a federal court found that it had inadequate justification to do so. As noted earlier, the Children’s Television Act of 1990 reimposed commercial limits of 12 minutes per hour on weekdays and 10.5 minutes per hour on weekends. The act also directed the FCC to reexamine the question of program-length commercials with respect to children’s programming. In a 1992 proceeding convened to implement the act, the FCC defined such a commercial as a “program associated with a product in which commercials for that product aired.”

OTHER POLICIES

Public Inspection File

All broadcast stations must keep certain documents and information open to public inspection at “the main studio of the station, or any accessible place” in the community of license during regular business hours. Public inspection file content must now be retained for the entire license term of eight years. In addition to permitting on-site inspection, stations must make photocopies of public file contents available upon receiving telephone requests for such contents. Under public file rules adopted by the FCC in mid-1998 and by Congress in the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002, stations may maintain all or part of their public file in a computer database rather than in paper files.

Set forth below is a summary of the contents of the public inspection file required under the new rules. Except where noted, the requirements apply to both commercial and noncommercial stations.

• Authorizations: A station’s current authorization (license and/or construction permit) and any documents that reflect a modification of or condition on the authorization.

• Applications: All applications filed with the FCC and related materials, including information about any petitions to deny the application served on the applicant. These are retained as described above.

• Citizen Agreements: All written agreements with citizens groups, which must be retained for the duration of the agreement, including any renewals or extensions.

• Contour Maps: A copy of any service contour maps submitted with any application filed with the FCC, together with other information in the application showing service contours, main studio, and transmitter site locations. This information is retained as long as it is current and accurate.

• Ownership Reports: The most recent complete ownership report filed with the FCC, any statements filed with the FCC certifying that the current report is accurate, plus any related material. Copies of the contracts listed in the report or an up-to-date list of those contracts are also required. Copies of contracts must be made available within seven days if the latter option is chosen.

• Political File: The requirements were changed by the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002. This law imposes supplemental public file requirements for certain issue ads that are not subject to the access, equal opportunities, and lowest unit rate rules applicable to candidate ads. The new requirements apply not only to ads placed by candidates for federal elective office, but also to national issue ads purchased by corporations, labor unions, public interest groups, PACs, etc., to present messages that support or oppose any federal law, regulation or policy, or that support or oppose any change in such federal requirements.

• On issues relating to any “political matter of national importance,” broadcasters and cable systems must retain in their public inspection file the following:

1. a record of each request to buy time

2. a note as to whether the request was accepted or rejected

3. the rate charged, if it was accepted

4. air dates and times

5. the class of time purchased

6. the issue involved

7. if applicable, the name of the candidate and election/office

8. the name of the purchaser and contact person and a list of the chief executive officer/board of directors

• All requests for time that a station receives from a candidate for public office, and a description of how the station responded to the request, are retained for two years.

• Annual Employment Reports: A copy of all annual employment reports filed with the FCC and related material. These are retained for the entire license term.

• The Public and Broadcasting: A copy of the revised manual (when it becomes available).

• Public Correspondence: A copy of all written comments and suggestions received from the public, including E-mail communications, regarding the station’s operation, unless the writer requests the correspondence not be made public, or the licensee believes that it should be excluded from the file based on its content (for example, defamatory or obscene letters). E-mail correspondence may be retained as described above. (Note that this requirement does not generally apply to noncommercial stations, but such stations may choose to retain letters from the public regarding violent programming. All TV stations are required to file with their license renewal applications summaries of any letters received regarding violent programming.)

• Material Related to an FCC Investigation or Complaint: Material that has a substantial bearing on a matter that is the subject of an FCC investigation or a complaint to the FCC about which the applicant, permittee, or licensee has been advised. This is retained until the FCC provides written notification that the material may be discarded.

• Issues/Programs Lists: The quarterly list of programs that have provided the station’s most significant treatment of community issues during the preceding three-month period. Each list should include a brief narrative describing the issues to which the station devoted significant treatment and the programs (or program segments) that provided this treatment, including the program’s (or segment’s) title, time, date, and duration. These are due on January 10, April 10, July 10, and October 10 of each year and must be retained for the entire license term.

• Children’s Commercial Limits: For commercial TV stations, quarterly records sufficient to substantiate the station’s certification in its renewal application that it has complied with the commercial limits on children’s programming. The records for each calendar quarter must be placed in the file no later than the tenth day of the succeeding calendar quarter (e.g., January 10, April 10, etc.). These are retained for the entire license term.

• Children’s Television Programming Reports: For commercial TV stations, the quarterly Children’s Television Programming Report on FCC Form 398 showing efforts during the preceding quarter and plans for the next quarter to serve the educational and informational needs of children. This must be placed in the file no later than the tenth day of the succeeding calendar quarter (see above). These reports are kept separate from other materials in the public file and are retained for the entire license term.

• License Renewal Local Public Notice Announcement: Statements certifying compliance with the local public notice requirements before and after the filing of the station’s license renewal application. These are retained for the same period as the related license renewal application.

• Radio Time Brokerage Agreements: For commercial radio stations, a copy of each time brokerage agreement related to the licensee’s station or involving programming of another station in the same market by the licensee. Confidential or proprietary information may be redacted where appropriate. These are retained for as long as the agreement is in effect.

• Must-Carry/Retransmission Consent Election: For TV stations, a statement of the station’s election with respect to either must-carry or retransmission consent. In the case of noncommercial stations, a copy of any request for mandatory carriage on any cable system and related correspondence. These are retained for the duration of the period for which the statement or request applies.

• Donors’ Lists: For noncommercial stations only, a list of donors supporting specific programs. This is retained for two years.

Operating Requirements

The legal guidelines for operation comprise one of the most important policies for a broadcaster. In the early days of radio, broadcasting stations went on the air when they pleased and where they pleased. Adhering to an assigned frequency was of no concern. With the passage of the Communications Act of 1934, broadcasting became highly regulated. Despite deregulation of many areas of station activity, the FCC continues to monitor technical operations very closely.

When licensees are allocated a channel for broadcast purposes, in effect they have entered into a contract. They must keep their signal on that channel and at the power allotted to them at all times. They are also required to run checks on their entire transmitting system and to note and retain the information gathered.

Licensees must observe FCC rules on the painting and lighting of towers, whether they own them or not. The FCC is now emphasizing observation of these rules and has an authorized $10,000 fine to deal with those who do not adhere to them. A similar initiative has been under way to ensure that all stations have Emergency Alert System equipment in operational order. The fine for a deviation is $8,000. Those stations with directional patterns must keep them within prescribed limits or be subject to a $7,000 fine.

Inspectors from one of the various FCC field offices arrive unannounced and inspect the station for violation of the FCC’s engineering standards and other rules. After the inspection, the licensee will receive either (1) no notice at all, if the inspector determines that no violation exists; (2) a letter alerting the station that a problem does exist that could, if continued, result in a violation or prevent the station from performing effectively; or (3) an official notice of violation.

An important fact for all managers of broadcast stations to keep in mind is that, no matter how good their programs are, no matter how grandiose their facility may be, or how efficient their sales staff is, everything within their command is just as good as the technical staff that keeps the station on the air.

Fines and Forfeitures

Sections 503(b)(1) and (2) of the 1934 act authorize the FCC to levy monetary fines and forfeitures for violations of its regulations or certain federal statutes. For a review of the violation classifications and the base fine for each, see Section 1.80(b) of the FCC’s Rules.53

Regulatory Fees

The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993 requires the FCC to assess annual regulatory fees. These “user fees” are separate and distinct from application fees, which were authorized in 1987. Collection commenced on April 1, 1994, and the FCC may levy a late fee of up to 25 percent.

Regulatory fees for radio are determined by class and market size and range from $350 to $8,775. Fees also are imposed on AM and FM construction permits. Television fees vary with VHF or UHF allocation and market size. Again, construction permit fees are assessed.

DEALING WITH COMPLAINTS

For the most part, stations only receive complaints when an individual or group is angry about a program, a news report, a commercial, an editorial, or something technical like “your darn station is coming in on my toaster.”

However, some people complain not only to stations, but also to the FCC. It disposes of most complaints by sending a letter to the complainant without ever contacting the broadcast station in question. For complaints involving political broadcasts or questions of access, the FCC encourages good-faith negotiations between licensees and persons who seek broadcast time or have related questions. In the past, such negotiations often have led to a disposition of the request or questions in a manner that is agreeable to all parties.

In general, the FCC limits its interpretive rulings or advisory opinions to cases in which the specific facts in controversy are before it for decision.

Written complaints to local stations must be kept in the public file, and management should act or react to the complainant as soon as possible. Radio and television station operators are in a business where the image of the station must be a positive one or the audience may simply turn the dial or shut the TV or radio off. Good public relations are important ingredients in the management of any electronic media system.

WHAT’S AHEAD?

With deregulation and some of the controversies that have ensued, the question now is what further changes, if any, will take place in the regulations and the agencies that enforce them. If the broadcast industry accepts the responsibility of self-regulation, deregulation may continue.

Accordingly, deregulation brings additional responsibilities for the broadcast manager. Some management decisions, especially in the area of programming, will have to be looked at in a different light without the federal regulations to guide the industry. If the industry does not take advantage of deregulation, it will find the old regulations being imposed once again. It is going to take time to determine whether or not broadcasters are willing to seize the opportunity to function in an environment similar to that of the print media. Responsible management will be the key.

SUMMARY

Traditionally, broadcast regulation has been based on the principles of the public interest and scarcity. The public interest remains intact. However, the FCC has effectively removed scarcity as a rationale.

The FCC was established by the Communications Act of 1934. It is the agency charged with regulating the electronic media but, in recent years, embarked on a program of industry deregulation. The Telecommunications Act of 1996 escalated further deregulation and electronic media consolidation. The law increased the participation of other arms of the federal government, like the Department of Justice, in communication regulation. Another agency, the FTC, polices advertising in broadcasting and other media.

Would-be and actual station licensees are required to file a large quantity of information with the FCC. Forms must be submitted to request authorization to construct a station and to obtain a license to operate. The FCC also requires submission of ownership reports and license renewal forms, among others.

Despite deregulation, the FCC retains and continues to enforce many policies. There are restrictions on the numbers and kinds of stations that can be owned by one person or entity in a single community and nationwide. Programming policies cover, among other content, political broadcasts, and the use of obscenity, indecency, and profanity.

Stations are required to maintain for public inspection a file containing copies of all applications to the FCC, ownership and employment reports, details of programs broadcast in response to community issues, and other information. They also must comply with operating requirements set forth in their license.

In this new era, broadcasters must show that they can operate responsibly without close regulation. If they do not, a reimposition of at least some of the terminated policies is likely. In fact, there is evidence of that now in the FCC’s localism initiative, the indecency zero tolerance, industry reaction to stiff fines, and in a reexamination of violence in programming.

CASE STUDY

WPOL-TV is the local news ratings leader in a presidential election battleground state. It is an open election, with no incumbent. The presidential aspirants and their supporters have beaten a path to WPOL’s door to buy time.