PREFACE

“One fact that is not in dispute is that there is a widening gulf opening up between art and commercial photography, between professors and professionals.”

—Bill Jay in Occam’s Razor

It is no new observation that throughout the history of photography its practitioners have been segregated into one of two distinct disciplines, professional or fine art practices. That this self-conscious distinction creates limitations for practitioners on both sides is evidenced by the large percentage of fine artists who attempt more or less successfully to support themselves in the professional fields and an equal percentage of professionals who vie for acceptance of their art work in galleries. The separation of photographic practices is perpetuated through a higher education system in which the overwhelming majority of photography programs emphasize one of the two disciplines: technical education (the goal of which is to train students to become successful professional photographers) or fine art practices (whose primary structure prepares students for success as fine artists). Although ideal in many respects, the system’s inherent drawback is that while the marketplace offers vast opportunities for both professionals and fine artists, academia’s singular-focus approach limits graduates’ chances of success, and inhibits the useful carry-over of techniques and ideas from one discipline to the other.

College photography programs situated within Technical Schools (those offering degrees in commercial, editorial, consumer portraiture, etc.) tend to organize curricula around the mechanics of the medium, producing graduates whose images demonstrate skilled craft and technical proficiency. Adept at using the most complex, state-of-the-art equipment and materials, the best graduates of these programs produce images demonstrating feats of technical perfection with eye-catching style. However, many of their best photographs lack any substantive meaning, and at worst their images miscommunicate, because these photographers are undereducated in the areas of photography and art history, visual literacy, critical theory, and aesthetics. These indispensable aspects of photographic study simply do not permeate most technical school curricula. As conceptual photographer Misha Gordin states, “The poor concept, perfectly executed, still makes a poor photograph.” (See Misha Gordin’s work in the Portfolio Pages of Chapter 1.) This fact is not lost on visually literate viewers such as editors, publishers, graphic designers, art buyers, gallery and museum directors and curators, not to mention the media-viewing public. On the other side of the educational spectrum, photography programs situated within Fine Art Departments emphasize the communicative nature of photographs—their content, theoretical and historical positioning, and meaning—but they do so often at the expense of time spent practicing the medium’s technical/mechanical side—its equipment and materials and their specifications, benefits, and limitations. The students of these programs produce images filled with intelligence, insight, passion, and depth, much of which is often lost owing to sheer lack of sophisticated technical accomplishment. Again, to quote Misha Gordin, “The blend of a talent to create a concept and the [technical] skill to deliver it,” is the necessary balance of ingredients for making successful photographs. I equate fine art photographers who create technically poor images to poets possessing limited grammatical skills; they may have volumes of insight to share with the world about a subject, but they lack the proper tools needed to successfully convey it to others. Taken to the extreme, the photographers emerging from most photography programs have for decades possessed a completely lopsided perspective of the medium; they practice professional or fine art photography in relative ignorance of the myriad ways the medium’s “other half” could inform and enhance their work.

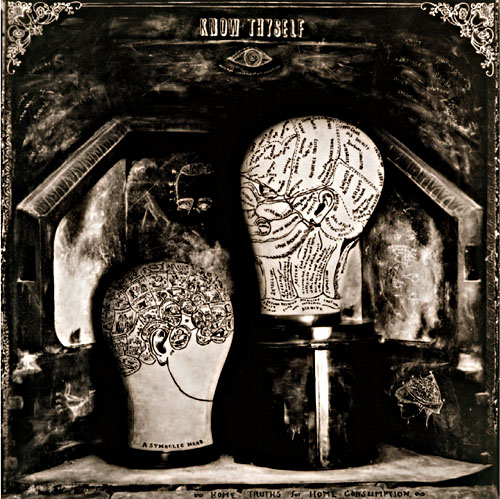

IMAGE © CAROL GOLEMBOSKI, OBJECT LESSON IN HEADS, 2004.

To complicate matters, with the advent and rapid adaptation of digital technology, it seems that a new fissure has been created, this one based on photographic media itself. During the last decade it has come to pass that academic programs have literally begun choosing between two discretely defined light-sensitive media—traditional or digital. This pressure to choose seems largely based on the desire to conform to their particular discipline or industry’s media focus, as well as the financial pressures that ultimately come to bear on academic institutions such as faculty areas of expertise, limited time to cover curricular material, and the simple matter of space limitations for either darkroom or digital facilities. Many programs (and practitioners) have rushed too quickly to recommend an either/or approach, suggesting that the decision to abandon traditional media and convert completely to digital media will advance those leaders who embrace it, and retire those relics who do not. This approach is short sighted in several ways: students tend to learn and practice only the technologies available to them through their academic program, so the richness and diversity of alternative media options go unconsidered. Also, an either/or approach neglects careful examination of the broader potential offered by maintaining both. History is full of examples of bad outcomes made so because of decisions that lacked proper balance, and there are simply no good reasons for photographic expression to suffer the same.

In addition to photography’s polarized academic structure and the advent of digital media, many students unwittingly set themselves up for failure in a particular branch of photography because they are unfamiliar with the dual nature of the medium when they enter a college program. Every professor knows scores of students who did not consciously choose the photography program they found themselves in. That is, they did not make informed decisions by sufficiently defining their future goals and applying to institutions that, through research, they learned would best meet those goals. Two years and tens of thousands of tuition dollars later, these students begin to understand (thanks to some formal education and practice in the medium) what direction they want to take in terms of their photography career. Unfortunately, too many of these students simultaneously discover that they are not in a photography program best designed to help them succeed.

The negative effects of these combined problems—polarized academic program emphasis, the pressure on programs to convert solely to digital media, and student ignorance of the range of potential careers in photography—can be mitigated by the actions of dedicated professors through course offerings which seek to simultaneously balance and broaden the way students engage in photographic practices. By designing a more holistic approach to photography education, graduates emerge armed with sound knowledge of the range of available tools, and are better able to define, choose, or change the emphasis of their photographic practice throughout their careers. One aspect of this type of mitigation is to develop courses based on the interconnectedness of photography’s technical and aesthetic elements, beginning with the primary technical elements from which all photographic images are made. By integrating hands-on practice with these technical elements with study and discussion of their inherent visual outcomes, photography programs offer students a more well-rounded education in the medium.

With this premise in mind, I created a portfolio development course for intermediate-level photography students; this course grounds technical understanding while deepening conceptual awareness and expanding aesthetic and visual literacy. The course has had incarnations as intermediate-level photography electives in technical programs, as well as aspects of intermediate-level required courses for photography majors in BFA programs. In addition to meeting with equal success in both technical and fine art programs, this course has made a remarkably seamless transition from traditional to digital media and everything in between because it is based on four immutable elements (which I discuss in the Introduction) inherent to the making of all photographic images. The success of this method of photographic training didn’t diminish with the inclusion of digital media because digital media didn’t change the elements that govern photographic image making. Even as the light-sensitive materials we use continue to change and evolve, the principles that make a photograph … well, photographic … stay the same.

The approach outlined in this book is based on a single bottom line: photography is a unique form of visual language, and as such is based on a specific visual grammar. The principles that govern photographic language have been understood and documented in various forms by many practitioners and theorists, notably in John Szarkowski’s The Photographer’s Eye, and Stephen Shore’s The Nature of Photographs. Anyone who studies a language intently and for a long enough time begins to know its grammatical structure. And a photographer who understands the grammar of photographic language, and who also has a curious and conceptual mind, can use it effectively as a communicative tool for the purpose of sharing their insights and interests, rather than merely demonstrating a particular brand of training. The most successful fine art, documentary, and professional photographers—those who produce work that transcends mere technical or visual accomplishment and has the power to enlighten, to educate, to heighten our perception of people, places, events, and things—share a common practice; they acknowledge through their work that the power of photographic image making lies in the interconnectedness of the medium’s technical nature and visual outcomes. When student-photographers are educated in an environment that emphasizes integration of technique and aesthetics, they are better able to create successful, meaningful images in any branch of the profession.

I have shared this course and its methods with other photography educators, and the quality of their students’ images and growth in understanding have been as impressive as that of my own students. Use of these simple techniques helps educators to bridge the institutional gap between technical and fine art practices, as well as the gap between traditional and digital media, and helps to ensure that students receive a comprehensive education in photography that will serve them well in the profession.