6

The use of concept art has been widespread in the game industry for some time, though the use of storyboarding is not as common a practice. Storyboarding is basically designing a series of sketches that illustrate how the story will unfold—much like individual panels in a comic book. They can be as simple as a sketch or as complicated as computer-generated graphics with motion. Either way, the purpose of the storyboards is to illustrate how the story will unfold within the parameters of the scene (time, location, and so on) and to help the team to understand the technical aspects of the frame, such as camera location, camera movement, and types of shots that will be used.

Concept art, on the other hand, are static art pieces created in great detail that help the development team understand what individual characters, locations, and scenes will look like. Concept art (and even storyboard art) can be helpful when you are making your initial pitch to a publisher and can get your team working with a unified vision for what the game will look like. They can also help programmers to understand the individual assets that will be involved with developing each level.

Making a detailed set of storyboards for each level will also do things that the basic concept art cannot. Concept art is used to establish the artistic elements of a particular character or location (level) and helps the animators and artists understand what those elements are supposed to look like. This includes the color scheme, lighting, and style of the art. Think of the storyboards as the tech side of the illustrations. The storyboards will illustrate how the character is supposed to get from Point A to Point B within the level/scene, what props will be present in the level, and the way the scene will actually look from a technical aspect: Where is the camera located? Is a cut-scene needed? What will the gamer see when moving across the level?

An Example of Concept Art from Capcom’s Lost Planet. Reproduced by Permission of Capcom U.S.A., Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Another great perk to the use of storyboards is the ability to experiment without the investment of much money. Taking the time to illustrate various ways to tell the story (flashbacks, playing with the timeline, and so on) can help determine which approach will create and evoke the most emotional payoff, as well as create the highest possible level of suspense or drama within the game.

6.1 Using Basic Design Documentation

As the basic design document will already contain a lot of information regarding the game, it can be used to help your artists create the storyboards needed for each level. The key things that should be extracted from the document include the story, the game features that will be used within the game (and set it apart from preceding games), and the major characters within the game. Getting the look of the major locations and characters down early on is a no-brainer, but how about the major features? For instance, if one of the game features includes the ability for the gamer to jump across great distances in the blink of an eye, this is something that can be illustrated in a series of storyboards. Not only will it give a visual representation of the feature, but it will give you a means for showing the publisher and team how that feature will actually work within the confines of the game.

Once the storyboards are actually finished, they can actually complement the design documentation and be an additional tool for the producers, engineers, and animators to use when hammering out production. They will also help you in a very basic manner: the more the game is actually storyboarded, the more focused the team will be on the actual levels that are being designed. This means that the budget will not be affected as heavily by reworking levels to accommodate new props and assets, as those would have been previsualized during the storyboarding process.

Being aware of the individual elements of each level/scene is very important. Putting them on paper before the programmers invest hundreds of hours of work into creating a level is a great way to keep from impacting your budget in a negative way. If you are creating a game that will feature cut-scenes within it, the storyboards will also provide a means to actually seeing how the game will transition between the levels and the cut-scenes and how the scenes can be kept pertinent to the gamer. Taking the time to will also illustrates any major holes in the story; because a series of storyboards is quite similar to that of a comic strip or graphic novel, the viewer should be able to look at the storyboards and see the story. If the team cannot determine the story from the visual cues within the storyboards, then there’s probably work that still needs to be done from the storytelling aspect.

Never Underestimate the Visual Impact of Games like those in the Resident Evil Series. Reproduced by Permission of Capcom U.S.A., Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Another key way that storyboards are used in the film industry is to help determine locations. As the locations are so vital to the look and appeal of a film and game, it is important that each level is impacted by where it takes place. It is not uncommon for producers to have no idea where a scene should take place (at least specific locations—it may be determined early on to feature combat on a skyscraper, but which skyscraper? What kind of skyscraper?), but once it is actually drawn in the form of a storyboard, location ideas will come to light.

Development Tip

![]() Because most storyboards are made during the preproduction process, you may not have actual artists/ animators working with the team at this point—and if you do, they are probably more focused on getting the concept art together. Consider using a computer storyboards program like FrameForge 3D Studio to do the work. In addition to helping with placement (you can move props around independently within the program), a program can actually show camera movement and character movement within the scene/level.

Because most storyboards are made during the preproduction process, you may not have actual artists/ animators working with the team at this point—and if you do, they are probably more focused on getting the concept art together. Consider using a computer storyboards program like FrameForge 3D Studio to do the work. In addition to helping with placement (you can move props around independently within the program), a program can actually show camera movement and character movement within the scene/level.

A video game is made up of quite a few independent levels, characters, and scenes; it is better to think of the individual components as complementary assets rather than thinking of the game in a timeline like Level 1, Level 2, and so on. Divide the story into the separate elements, including the character profiles, locations, events that will take place, history of the situations, and related story issues. Once you have the concept art pieces for the characters and locations completed, you can then move on to the designing of the actual scenes.

When you begin sketching out the main levels as they would appear to the gamer, the storyboards can point out major holes in the game play, as well as allow the game designer to determine the types and quantity of props within the level. This will be helpful when planning exactly what the gamer will be able to interact with and what will be static scenery within the game.

A great way to tackle the storyboarding of a level is to use a method known as “reverse storyboarding”. As the designers probably know how the level is supposed to end for the gamer, storyboard that scene first. Then work your way back through the individual scenes and levels towards the opening picture. Again, because this is working the level in a nonlinear way, it will help keep the individual steps in the level independent and give each of them their own strengths. Most game levels are in many ways self-contained, so working them out of order should present few problems. You can also use screenshots to set up a flowchart that illustrates the various paths that a game can take and how they relate to each other—which is very useful, as you want gamers to be able to take different approaches to playing the game.

Some great questions to ask as you are storyboard a level are: What type of camera placement is ideal for this scene? Are there any important props or vehicles in the level? What environment elements will affect the scene—is it day or night? Rainy or fair weather? Does all the action take place inside, outside, or both? Is any special lighting necessary? What kinds of special effects will take place—explosions? Fires? These are all questions that can be answered within the storyboards.

Midway’s Game Blacksite: Area 51 Uses Solid Framing and Camera Techniques to Maximize the Production Value of Environments Within the Game. Reproduced by Permission of Midway Games. All Rights Reserved.

The storyboarding phase consists of four different tasks:

Decide the format and detail of the storyboards. As the individual illustrations can be made in any size, it’s best to determine the screen ratio that the game will be projected in and then use the appropriate ratio in the storyboards. Will the game be a “fit the television” game (usually called 4:3 ratio in the film industry) or will it be in a wide-screen format (or both)? Also, in how much detail will the scene be illustrated? Do you want a storyboard for every action that takes place in the level, or will it be necessary to storyboard only the key moments?

Create thumbnails. These are basic drawings that are small (the size of a thumbnail if necessary) and contain very little detail. The purpose of the thumbnails is to just get the placement of the individual assets within the level and to show the viewpoint of the scene—that is, what the camera angle will be. In the film industry, many directors get by with creating only thumbnail storyboards. Because concept art generally illustrates the look of the scene, as well as the color schemes and similar details that are involved, the storyboards need show only the staging of the scene. With a video game, it will probably be necessary to move on to the next step.

Create 2D storyboards. Now that we have the format of the drawings and the thumbnails have been created, we can move on to creating a higher-quality rendition of each level/scene. In addition to doing the same things that the thumbnails do (specifically, the layout and camera angle of each scene), the purpose of the 2D storyboards is to capture the mood or emotion of each scene. Is it a dark moment within the game? Does the lighting capture that? Care must be taken, though, to not create storyboards/images that cannot be captures in the game. At this point, the game designers and producers should be consulting with the storyboard artist to insure that each scene is storyboarded accurately. Once high-quality 2D storyboards are created, the team can move on to the use of 3D storyboards if needed.

Create 3D storyboards. This step involves the use of a story-boarding program or animation software. Although it’s completely acceptable to make 3D storyboards with the use of Maya, 3ds Max, or Lightweave, most storyboard artists prefer to use either a filmmaking storyboard program or to use 3D models from Poser or DAZ Studio. The advantage of using 3D storyboards is that the development team can actually see how the level will look to the gamer, how to use lighting, and to adjust camera angles. Some story-boarding programs even have the ability to have movement in the frame so you can see how a character can move within the scene. Moving storyboards are usually called “animatics” and have been wide used in the animated film industry.

Development Tip

![]() StageTools has two programs available for free demo online that can help with creating animatics. Go to http://www.stagetools.com and download the software demos of MovingPicture and MovingParts for a trial run. If you’re interested in creating 2D storyboards, check out the freeware program Storyboard Pro at Atomic Learning (http://www.atomiclearning.com).

StageTools has two programs available for free demo online that can help with creating animatics. Go to http://www.stagetools.com and download the software demos of MovingPicture and MovingParts for a trial run. If you’re interested in creating 2D storyboards, check out the freeware program Storyboard Pro at Atomic Learning (http://www.atomiclearning.com).

If it has been determined in preproduction that the game will include cut-scenes, storyboards can be especially helpful in this arena. As cut-scenes mean that the gamer will not be interacting with the action, they can be thought of as mini-movies within the game. In this respect, the storyboard process can be approached exactly like that of a film. In addition to the illustration pane, each drawing can feature a description panel underneath that explains any important information that is not in the storyboard. The description panel can sometimes include information regarding dialogue, special effects, or camera movement—usually, though, the camera movement in indicated in the actual panel with use of arrows.

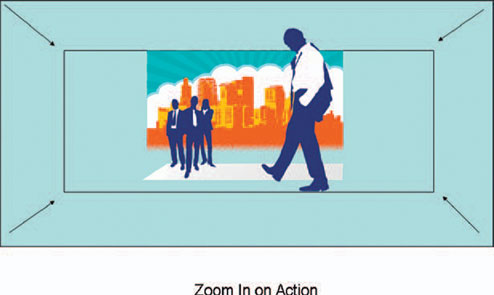

Example of a Storyboard with Camera Movement and Description.

As you construct the storyboard sequence for the cut-scene, think of the illustrations as a comic book or graphic novel; the drawings should move forward in a logical narrative and tell the story visually. This can be easily accomplished by making a short “script” that describes for the artist what should appear in each panel that will be created. The basic storyboarding process can be described in the following four-step process:

Step 1: Framing. Once you know the size of the storyboard, you must first determine the size of the objects within the frame. This can usually be done by determining the type of shot that is within the scene. By simply marking the storyboard as a long shot or a medium shot, the artist can then determine the size of the characters, props, and so on within the frame. The different types of shots are discussed in the chapter on cinematography.

Step 2: Camera Angle. Will the viewpoint be from down low, or high above the characters? Note on the storyboard whether the camera will be on an even “eye line” (straight in front of or behind the characters), a high angle, or low angle.

Step 3: Depth of Field. This is the same thing as a cinematographer choosing a lens. How much of the scene will be in focus? Do you want everything to be crystal-clear (like in documentary footage), or will the background be blurred? How far will the background be from the objects in the foreground? The choice of depth of field is an artistic decision and can affect the emotional impact of the scene, so choose carefully.

Step 4: Movement. If there is going to be any movement within the frame, it must be annotated either within the frame with arrows or beneath the frame with a description panel. Either way, all movement (including the camera itself) must be indicated for the artist.

The use of an Overhead Camera Angle Helps Reinforce how Small you Within the Scope of the Universe when you Begin Playing the Game Spore. © 2006 Electronic Arts Inc. Electronic Arts, EA, The EA Logo and Spore are Trademarks or Registered Trademarks of Electronic Arts Inc. In the U.S. And/Or other Countries. All Rights Reserved. All other Trademarks are the Property of their Respective Owners. EA™ Is an Electronic Arts™ Brand.

Once all these steps have been taken and the storyboards are scripted, the artist can now create a graphic representation of what your cut-scene will look like. This storyboard will be the roadmap that the animators and artists use when creating the scene.

6.6 Storyboards and Interactive Media

In addition to use within the film industry to help with setting up and designing individual shots in a movie, storyboards have also been used recently to help with the designing and maintaining of interactive media and Web sites. As Web sites can also incorporate audio, video, and graphic elements in a nonlinear fashion, storyboards are a great way to illustrate the various ways the site can interact with visitors. In this sense, the storyboards can be looked at as a sort of flowchart or site map that shows the interactivity of the individual elements of the Web page. This can help when designing the online site for the game you are producing.

It is also becoming more prevalent within the game industry to involve an “alternative reality game” (ARG) with the release of a title. Bungie’s Halo 2 was preceded with the ARG “I Love Bees”, Halo 3 was kicked off by the ARG “Iris”, and even television series are now using the concept of an ARG (the program Lost held an online ARG called the “Lost Experience”). Because alternative reality games usually include online content that is meant to interact with live action performed by the gamer in the real world, storyboards are a great way to map out how events will unfold between the Web site and reality, as well as the path that the gamers will take in the real world while exploring the game.

The Halo 3 Alternate Reality Game Help Fuel the Fire of Anticipation before the Game’s Release. Copyright © Bungie LLC and/Or its Suppliers. All Rights Reserved.

Interview: Mathieu Raynault, Digital Matte Painter

Mathieu Raynault is a digital matte painter (digital matte painting is the art of creating traditional matte paintings—usually background/environment work—electronically, using a combination of scanning, drawing, and coloring using a computer and specially designed software) and has worked on films like 300, Star Wars: Episode II Attack of the Clones, two of the Lord of the Rings films, and King Kong. In addition to his film experience, he has also produced art for television and the game industries (Prince of Persia III, The Act of War, and Men of Valor). You can see examples of his work on his Web site (http://www.raynault.com).

Newman: Typically, what kind of information is given to you by a client regarding a new scenic piece? Is it usually very detailed information, or do you generally get a lot of room to inject your own artistic input into the scene?

Raynault: It really depends on the project. I do often have to provide sketches and concepts early in the process in order to start dialog with the director or art director. In these cases I am involved early, and my creative input is quite significant. Though, sometime like on Star Wars for example, I would get a pretty detailed concept art piece, basically a painting that was done by one of Lucas’s concept artist, establishing composition, color palette, mood and lighting. On cases like this, my job becomes solely to create the most believable photorealistic image based on the concept.

Newman: You’ve produced art for film and game projects. What has been some of the major differences with working in these two industries?

Raynault: It’s been quite similar in fact. My contribution to video games was on cinematics only which are basically short films. So for a matte painter, it’s almost the same. The only difference being that cinematics are full CG productions, similar technically to films like Shrek or what Pixar does. Everything is created through 3D software and the matte painting works to be part of that.

Newman: What values have you taken from working on film projects (like Star Wars: Episode II and the Lord of the Rings movies) and incorporated into your game pieces for Atari and Ubisoft?

Raynault: I think one of the good things learned while working on these big films is the ability to create photorealistic images, yet stylized with a touch of fantasy in it. Finding this balance is always a challenge and is more and more in demand in game cinematics. So technically it means to be able to mix painting skills with a dose of CG and photographic knowledge. Working on these films also lets your eyes see and record beautiful D.O.P [Director of Photography] work as you sit down in those dailies seeing pieces of the film over and over. In our field you have to literally “eat” as much beautiful and impactful imagery as you can. The more photographic and filmic knowledge you accumulate, the better you are at judging your own work. And that is just one more opportunity!

Newman: Describe the communication between you and the team that will be designing animation or action over the scenes you have created for a game cinematic (cut-scene). Could the direction have taken any lessons from the film industry?

Raynault: Yes, I think there is still a lot to be learned by the cinematic people. But it’s not necessarily from me! It seems that the standard in these teams is to hire fresh-out-of-school CG artists, which is totally valid, but unfortunately there is definitely a lack of movie-making knowledge in the equation. To me, if you want to create a nice short film before your video game or in the cut-scenes, you have to insufflate as much movie language as you can in it. This is valid in the art direction side of it, but also in the design of the cameras, use of lenses, and so on. I think it means hiring live action directors and art director to pair with CG people. To me, that is the ideal way you create rich collaborative teams.

Newman: What’s your workflow like? How long does a piece usually take to finish?

Raynault: A matte painting [MP] for a film usually takes around two to three weeks of work. I usually start with some rough concepts and sketches and once it is approved, I move forward to create the final piece using whatever techniques and cheats to speed up the process. If it’s a cityscape type of MP I will use a 3D software to model basic geometry, texture it, and light it to give me a base image. From there, I will use painting and photographic techniques in Photoshop. This is where most of the important work happens. Once I have a satisfying image, it will either be projected back on 3D geometry to allow a camera move and parallax, or it will go straight to compositing if, for example, it’s a lock off camera with foreground live action to be added in front.

Newman: What are the advantages of working digitally as opposed to creating a hand-made piece of art? How has technology affected your quality over the years?

Raynault: It is now impossible to achieve a matte painting without the use of the computer. The expectations now are way higher than they were twenty years ago. Audience can detect easily if a background looks painterly. That is why a final matte painting nowadays, even though it has been created with some painting techniques, contains no visible brush strokes. It became sort of a “created” photograph more than a painting, and that’s why it has to be done digitally.

Newman: When trying to create a more cinematic game, what kinds of elements do you think need to be present in the artistic design to give it that kind of scope?

Raynault: The key elements to me are lighting, mood, and camera design. Designing live-action-like camera moves, choosing the right lenses, and creating interesting composition is a really big challenge in video games. And of course, establishing great direction of photography and replicating filmic lighting effect adds a lot to the look of game. The more you can get away from the perfectness of CG, the closer you’ll get to a cinematic look!

Newman: You’ve managed to achieve a great standard in matte painting. What have been some of the better pieces of advice you have gotten over the years regarding working as an artist?

Raynault: In matte painting, one of the things you learn early on is that even though you are the creator of nice noticeable film background, it is not your art. You are part of a team trying to achieve a look for a film. Ultimately, you work for a director’s visions and you achieve it within a group of people. It is learning to separate your own art creation from your job. It is still really fun to be a matte painter but it has nothing to do with being a painter.

Newman: What advice of your own do you have for art students wanting to work in the video game industry?

Raynault: Well, I am maybe not the right person to answers this, as my main field is the movie industry. But if, like in my case, you want to be involved in the image creation side of your industry, I would suggest trying to put together the best portfolio you can, containing traditional art pieces as well as digital art. The more you show your education is complete, and that you have explored many paths in art, the better it is. The students that have impressed me over the years were always the one that managed to present movie-like shots in their portfolio, achieving photorealistic and highly stylized looks with challenging concepts and strong art direction. Also, I would be careful with these eight-month CG school programs that guarantee you a job in the industry. They are not necessarily bad, but I think they need to be preceded and combined with more traditional education.