10

Though there are already directors in the world of game development—specifically, the creative directors and technical directors—when I use the word “director”, I’m speaking of a person who actually works with actors. Dealing with actors during the motion capture process and while recording voiceovers are the primary areas we can address when discussing directing during game production, but there are several other areas that can be influenced by the use of solid techniques used by film directors. These include: directing concept meetings, location scouting, creating a unique vision with the cinematographer and/or engineering department, and making sure that all aspects of production are in sync with the script.

There is another kind of director in the game world as well— the person who actually directs the cut-scenes within a game, though this person is usually called a producer. As these cut- scenes usually double as at least part of the game’s trailer and is the first asset to be used in the game’s public relations campaign, this can be an important job during production. This type of producer is very similar to people in the film world that direct animated movies, so I will discuss this role as well.

When a new director is brought on board to direct a film, the first thing he or she does is take a look at the script and then organize and conduct a series of concept meetings.

A “concept meeting” is the first time a film director meets the key participants from each department on a film shoot. There will be many meetings similar to this during preproduction of your game, but the most important thing to take away from a film’s concept meeting is the use of department prioritizing. Besides making the artistic decisions regarding each area of production (for a film, this would be wardrobe, locations, props, and so on), there is a process of prioritizing the elements that are the most important and must come in under the budget and schedule first. This concept is equally important in game development; while in preproduction, it is important to implement the idea of the concept meeting to prioritize the features and levels that most clearly make the game unique and to get those into the game under the current budget and schedule. After these tasks have been identified, you will have a clear, prioritized list of assets that the coders and artists will have to begin production with.

With a Clear Cut Story Already in Place, Concepts for Games like Tom Clancy’s Rainbow Six Series Become much Clearer. Reproduced by Permission of UbiSoft. All Rights Reserved.

Another key point to conducting concept meetings is to get input from the heads/leads of each department—a system not unlike scrum, but more condensed and of longer duration. If you have properly developed a script for the game and it was distributed throughout the development team, everyone will have their own input as to what certain aspects of the game should look like and play like. Listen to them. One of the major advantages that the film industry has over the game industry is the ease of collaboration that exists in production. Nobody can make a film by themselves. This is true of games as well, so use it to the production’s advantage.

Listen to the suggestions and ideas that each lead/department has and decide if they have merit. By incorporating their suggestions, you are fostering a sense of team building and you will not alienate any of the folks working on the game. Most of the time, discussions regarding artistic choices will be about the particulars of the game—but sometimes, the issue is more about control. When you hire experienced professionals to work on a game, sometimes they feel that their opinion is worth more than everyone else’s. Be diplomatic about the issue, but nip this behavior in the bud immediately. Maintain your sense of vision and make sure that everyone on board is in sync with you.

Learning how to keep the team on the same page as a creative or technical director is a full-time job. It involves meetings, preparation, and communication. As discussed in earlier chapters, there are several tools at your disposal for keeping the original concept of the game in place as production proceeds. There are the aforementioned wiki pages, scrum, full blown meetings, emails, and so on. But how about command central?

Several prominent film directors are well known for keeping a sort of “motivational area” in the production offices. This is a place where the original concept art resides, character boards dot the walls, and even props/environmental pieces are kept. All of this effort is done to provide a place where artistic meetings can be held to make sure that everyone understands the central themes and look of the film being produced. This type of approach can also be taken at game studios. I have actually seen development teams put up concept art around the studio—but never to the extent that there is an actual meeting room where the creative and technical leads can go host a meeting and literally be surrounded by the atmosphere of the game.

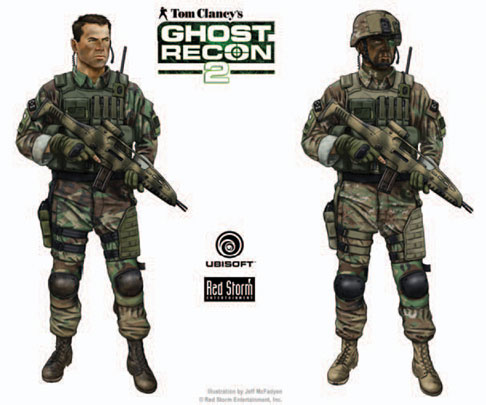

An Example of Character Concept Art from the Game Tom Clancy’s Ghost Recon Advanced Warfighter 2 By Ubisoft. Reproduced by Permission of UbiSoft. All Rights Reserved.

At any rate, communicating on a daily basis with the leads about the logistics of the game is a must. Just make sure that in addition to the daily delta reports and tracking the status of the next milestone, you are constantly touching base to make sure that all the artistic decisions made regarding the game are still in place and that all the team is working with the same goals and vision—just don’t get into the realm of meeting overload!

Decisions regarding the locations used in a film ultimately come down to the director. A good director will choose locations that fit the needs of the budget but reflect the greatest amount of production value. A good location will also mirror the script as much as possible, so that on-the-spot changes will not have to be made during production. Locations in a video game on the other hand are usually a reference tool for the artists and designers so that they have a sort of road map when creating levels. Don’t underestimate the importance of this, though!

Producers of Midway’s Blacksite: Area 51 Actually Went on Location to Rachel, Nevada During Preproduction of the Game. Reproduced by Permission of Midway Games. All Rights Reserved.

Lines of description in a script are often very succinct and contain only the barest amounts of information. An example: “Exterior Mountains, Winter.” What kind of mountains? Are they snowcaps and really high? Are they low and flat? Are they in a heavily wooded area or maybe flatlands? The obscure language can make for conflicts in the art department and get early concepts off to a bad start. By scouting actual locations and taking pictures of the areas that illustrate levels in the game, you are providing materials for the production team to work from. You are also introducing a level of photorealism to the game; some people may think “cartoonish” when thinking of how an environment looks within a game—by showing them actual photos, they may take a more realistic and cinematic approach to designing the environments.

Working with actual locations is especially important when depicting real places in a game. Though you may alter the interiors of places to suit the levels of the game, keeping environments as realistic as possible will foster a level of immersion that created locales cannot match. Even fantasy games can use the information gathered at location scouts to create more realistic and cinematic environments. It is also important to use locations that have versatility. The more levels you can create from a single location, the better. This helps the schedule and therefore the budget.

The best approach is to take all the locations listed in the script (these will be extracted during the script breakdown process), prioritize them, and then brainstorm to see whether there are locales that can accommodate several different levels. For instance, one level might take place in a forest and another may take place in a research center. By choosing an observation station in the middle of Ozarks as your location, you kill two birds with one stone.

If your budget is such that flying to exotic locations is out of the question, don’t forget about using books that feature detailed photographs of almost any site in the world. Your game doesn’t have to suffer for lack of the scout.

Great Locations Contribute to the Awesome Ghost Recon Advanced Warfighter Game Series. Reproduced by Permission of UbiSoft. All Rights Reserved.

10.4Working with the Cinematographer

Because games do not have a cinematographer on the production team, the typical form of collaboration that exists between a film director and film cinematographer will be less obvious. The camera angles, framing, and other such aspects of a game are all controlled by those who are creating the code, so it is essential to develop a strong rapport with the lead of that department regarding the artistic choices of the game. Game cinematography has come a long way and the more experienced game engineers now have a strong grasp of the basics of cinematography; if your lead does not, I suggest reading Real-Time Cinematography for Games by Brian Hawkins (Charles River Media, 2005).

Because there is an entire chapter (chapter 7) devoted to game cinematography, I will not belabor it here. Just remember that choices made regarding cinematography should be made by the game’s producer or creative director, as they would be made by a film’s director. It is the job of the game’s programmers to get the cinematography up to par, but it is your job to direct them.

Once the actors have been cast for the voiceover work (and for the motion capture), they must be directed during the recording sessions. There are several steps that you can take to make sure that you get the best possible takes during the session. First, you will want to make sure that the actors have gotten the script as early as possible. This step gives them time to memorize their lines and get comfortable with speaking the lines (especially if there are any technical or difficult phrases in the dialogue). You can also ensure the actors are on the same page as you with direction by annotating the script with any notes that are important, such as indicating when a line is yelled or when a particular piece of dialogue is tinged with a particular emotion.

When the actors have arrived at the studio to record, sit down with them and make them comfortable. As they have had time with the script to learn the dialogue, they will usually be put at ease with a simple conversation. Once everyone is acquainted and the studio is ready to proceed, move into the recording area. The various lines that must be recorded should be listed on the script and annotated with the information that you will use to store the data for incorporation into the game. Begin with the first line, and once you are happy with the recorded piece of dialogue, move on to the next.

Hopefully, there will be no major snags with getting what you need from the actors, but if you do remember to be tactful and to carefully explain the context of the spoken line to the actor and the desired emotion you want—just know that actors can be sensitive to “line reading” exactly by the numbers. When you hire an actor, you are also hiring their personality, so expect it to be injected into the dialogue. Usually, most conflicts arise from confusion. Clarify the scene and what you want and most situations are quickly remedied.

Capcom’s Lost Planet: Extreme Condition Features well-Executed Dialogue. Reproduced by Permission of Capcom U.S.A., Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Working with motion capture also has the added logistics of attaching motion capture equipment to the actor (so allow for more time with the actor at the studio) and blocking off the movements that will be recorded during the session. Just as you did with the voiceover actors, make sure to send the actor a list of all the shots you want as soon as possible so that he or she can rehearse (it may even be a good idea to rehearse and direct the actor prior to the actual date of recording to make sure that he or she knows what will be required). As movements may be limited by the capture equipment, make sure that each action is done succinctly. It’s also a good idea to record the session with a video camera. If the session goes well, you can have the recording to use for future productions (you can also use a bad session as a “lesson learned” during the postmortem of the game.

10.6Script Supervision and Continuity

On a film set, there is a person called the “script supervisor”. This person is responsible for making sure that continuity is in place and that all the various scenes that are being shot are being done so with a singular look or style. A script supervisor is also responsible for making sure that every prop ends up where it is supposed to be when moving on to the next scene (sometimes a very tedious job). Continuity within a game is a big issue as well. This task should be approached from the artistic and creative slants and implemented from the very beginning.

Creative continuity is as simple as making sure that all assets are accessible to the entire team. When an artist or animator is working on a new character, he or she will want to make sure that it is in sync with all of the game’s other assets. The easier this is to accomplish, the more continuity and consistent style you will have within your game. It can also mean voicing opinions during scrum regarding certain elements that do not feel right or seem to match up with the rest of the game. Encourage individual team members to inform the leads when this is the case. And listen to them! Because they are working on the small details of every asset within the game, they are much more intimately familiar with them. If minor changes need to be made to a look, environment, or even the script, then do it. Use this collaboration to produce the best possible game.

On the technical front, good continuity is something that you may want to ask the quality assurance department to be particularly vigilant with. How many times have you played a game— an FPS, for example—where the enemy was killed using a technique on one level, but on the next level it simply did not work at all. Why? Nothing changed, so what happened? Bad continuity. Keeping consistency throughout the game will help with immersion, keep frustration levels down (and therefore the fun levels up), and simply make the world you have created seem more real.

More and more, it is becoming the norm to have producers that are specifically skilled at creating cut-scenes and game trailers. Although for immersion’s sake, it’s best to keep the cut- scenes at a minimum—or at least keep them extremely short— there are usually at least two in a game. The “mandatory” two cut-scenes you’ll find within a game will be one at the very beginning of the game to introduce the story and one at the very end of the game when you’ve “beaten” the main story line. Arcade-style games may contain no cut-scenes at all, but instead show an animation on the menu screen. Either way, the cut-scenes designed for the game usually double for at least part of the game’s trailer.

The Marketing Department will Thank you for Producing well-Developed Trailers. Check out the Trailers Online for Turok. Reproduced by Permission of Disney Interactive. All Rights Reserved.

Because a game trailer (and an in-game cut-scene) is a sort of mini animated movie, you can use a scaled-down version of the production process to create them. In other words, because you know the story of the entire game, create a small script of the story pieces that will be used within the trailer, storyboard them, then create the art/environments and develop the scenes. It would be wise to take a long look at the cut-scenes that will already be within the game play and then take as much as possible from them for the trailer. This approach keeps the costs and time constraints down for creating trailers.

Of all the producers in the game industry, producers who specialize in cut-scenes and trailers are the most film-like and usually have the highest population of individuals who have been educated at a film school. As cut-scenes/trailers are not interactive, it is necessary to make sure that the tone and style of the game are evident to gamers who watch them. Another concern will be the marketing department. Before writing the script for the game trailers, consult the marketing department to see what features or elements will be the focus for selling the game and include those elements in the trailers. This step will make the PR folks very happy. It will also take some of the heat off you if anyone dislikes the trailers.

Again, script it out and storyboard it first though. This lets the creative director and producers take a look at what you’re going to do and make any changes or suggestions.

10.8Cut-Scenes Versus In-Game Cinematics

As mentioned prevously, a game ideally has as few cut-scenes as possible. If you were told that for every minute of time you force a gamer to watch a cut-scene it takes that same gamer about thirty minutes to get fully immersed into the game again, you would keep the amount and duration of cut-scenes at a minimum, wouldn’t you? Well, for some gamers, this is exactly the case. It’s understood that a short cut-scene should give you an idea of what’s going on at the beginning of the game and that an ending will be provided for you to get that last bit of satisfaction from conquering the game. But to force gamers to constantly watch extended cut-scenes for game information is simply a crime. It’s not a good cinematic experience and it’s not fun interactivity. It’s frustrating. And, of course, the absolute worst crime to commit is to provide no way for the gamer to press a button and skip the cut-scenes! If a particular level is hard, and a gamer must make many attempts at beating it, watching a mandatory cut-scene creates huge frustration and anger.

Ubisoft does a Great Job of Integrating First-Person Perspective Cut-Scenes in the Game Far Cry Instincts: Predator. Reproduced by Permission of UbiSoft. All Rights Reserved.

If you must provide information within the game, do it during the game play as much as possible. What if a movie paused the action and took you to a text-only screen to let you read about the background of the next scene? Would the movie be made better by the addition of more information, or would you lose all suspension of reality and become disinterested? Some games, like Ubisoft’s Far Cry Instincts: Predator, have done a great job of keeping all dialogue and info in a first-person format within the game.

One of the biggest things you will hear in game circles when discussing making a game cinematic is that most producers think of a cinematic game as having more cut-scenes and more dialogue within the game. This is exactly wrong. A cinematic game is immersive, real, and fosters the suspension of reality, which means fewer cut-scenes and less dialogue.

Interview: Jay Duplass, Director

Jay Duplass was born in New Orleans and studied film at the University of Texas in Austin. In 2002 Jay collaborated with his brother Mark on This Is John, a short film shot digitally for $3 dollars. It was accepted into Sundance (2003) and earned the brothers a representation deal with William Morris. They returned to Sundance in 2004 with another digitally shot short, Scrabble. The following year, they premiered their third short, The Intervention, at Berlin (2005), where it won the Silver Bear and the Teddy Award. 2005 also marked the release of Jay and Mark’s feature film debut, The Puffy Chair, which premiered at Sundance (2005), won an audience award at SXSW (2005), and was a part of the “best of the fest” at Edinburgh (2005). Jay recently finished work on the Duplass Brothers’ second feature, Baghead, and is now working on his third feature film, The Do-Deca-Pentathlon.

Newman: There has been a strong convergence between the film and game industries in the last few years. What elements do you see in video games that remind you of movies? What characteristics draw you, as a film director, to a video game?

Duplass: Well, to be honest. I don’t really play video games, ‘cause I’m afraid I’ll get addicted and then I won’t get anything done. My brother Mark, however, is addicted to BrickBreaker on his phone, and had to go cold turkey during the shooting of our last film.

Newman: You are credited as cinematographer on your last film, Baghead. What is your process regarding directing the camera, or at least knowing the specific type of framing or shot you want in a scene?

Duplass: My process is to not plan things out and to let the actors do their thing and to capture it as it happens. In terms of framing, I definitely have axis and look space, and so on in the back of my mind, but mainly I just try to not think, and just shoot what I want to see.

Newman: You are also credited as the screenwriter for your last two features (The Puffy Chair and Baghead)—do you find it hard to adapt the work of an outside screenwriter or author to the screen? How would you describe the artistic process of interpreting words to images?

Duplass: I don’t really think of it as adapting words to screen. I think of the screenplay as a template and a starting point to get things rolling. Then when we get onto set, I try to just foster whatever the actors are bringing that day, make sure it works in the whole scheme of the movie, and just get the most natural and interesting stuff I can get.

Newman: When you’re coming up with characters for your films, to what extent do you actually develop them? Do you have pretty detailed character breakdowns for your movies?

Duplass: We mostly base our characters on people we’ve known. So we don’t really create them out of nowhere. We don’t do breakdowns unless we have to. We mostly just talk with our actors about them and tell them all the funny and wonderful and horrible things about them and try to get them inspired about who that person is. But more than that, it’s about finding out what the actor is inspired by, and then going down that path.

Newman: Being an independent film producer, I’m sure you’re always looking for ways to keep your budget down when shooting a feature film—such as avoiding exotic locations. In your opinion, what kind of impact does your choice of locations have on the cinematic value of your movies?

Duplass: Well, our movies are really about domestic situations on some level—situations that most of us would find ourselves in—so we’re a bit lucky in that we don’t feel like we need exotic locations … yet.

Newman: Another aspect of shooting independent films involves the use of “noncelebrity” actors—a concern for most independent video games as well. Describe your approach or method for casting key characters in your movies.

Duplass: Our characters are based on people we love, and think are hilarious. In terms of casting for that, it’s all about actors we love and are inspired by. We put them together and try to make it feel real . try to find life in there. In auditions, we see things, and it either opens doors and excites us or not.

Newman: What about directing actors with little or no experience? Is there an approach that has worked well for you on the set?

Duplass: The main thing I tell nonactors is not to try. There’s nothing they have to do except be there and be themselves. It’s my job to elicit anything that I want. So they don’t have to worry. It’s all about disobligating them in a way. I tell them that they’ve done all they need to do just by being there, and the rest is up to me. In that way, you eliminate any “acting”, the behavior is real, and then you can just try to add things as you go. But the most important thing for our movies is that the underlying behavior is realistic and genuine.

Newman: Do you think the game industry has affected the film industry in its approach to style or content? What about the influence of film upon the game industry?

Duplass: Absolutely, they both affect each other. It seems that gaming has become more narrative.

Newman: In your position, I’m sure you are approached quite often with scripts, ideas, and books for possible future films. How do you determine whether what you are reading (even when it’s your own work) will translate into a great film? What elements do you look for in pitches and proposals that indicate a great project?

Duplass: To be honest, we really don’t read that much. We spent one year reading hundreds of scripts our agent sends, and realized that the odds of us finding something that fits us more than something we’d write for ourselves is extremely low. So the time is just not worth it. That being said, this sounds simple and corny, but you just know when it’s right to do something. It’s all about instinct and trusting your gut. And more specifically than that, we always are asking ourselves, are we the best people in the world to make this particular film. If not, we turn it down.