If you’ve been through the whole book, you’ve created some images and learned how to render them, so you’ve got yourself a portfolio, right? Wrong! The first rule about putting a portfolio together is that the work must be your own. I’ve put this in emphasized type because it is the single most important rule when sending off your portfolio and applying for a job.

It’s okay to show your friends and family all the great renders that you’ve created by working through this book, but if you’re going to send work off to a professional reviewer, you’ll have to throw it all out and start again, from scratch—sorry! The main reasons for this are as follows:

• Although you technically completed the projects in each chapter, don’t include them in your portfolio, as it’s not all your own work. You’ll need to create similar pieces of work based on the skills you’ve learned. That way, the projects won’t be recognized by anyone as a tutorial and will truly be your own creation.

• If the reviewer recognizes one piece of work in your portfolio from a tutorial that they know or a book they own, they will most likely throw the whole portfolio out and you’ll never get another chance with them, or possibly even that company, ever again.

• It’s important to be original. Recruiters get sent lots and lots of portfolios every day. Although you need to demonstrate that you can do the basics (as covered in this book), you’ll need an edge to impress them. Also, if you’ve bought this book and created a portfolio from it, you probably won’t be the only one. So take what you’ve learned, apply it to a few different models, themes, and subject matter and create a stunning portfolio of your own work, which you can be truly proud of.

If you feel that you’ve gone through this book and completed some or even all of the tutorials but you’re not quite ready to apply for a job (or don’t even want to), then there are a few things that you can do next:

• You can go back through the tutorials that you enjoyed and redo them, this time creating something similar using your own reference or concept material.

• You can browse the texture and reference photo folders included on the DVD and build something from those.

• You can take some of your own reference photos and build something completely new, from scratch.

• You can even create something completely new that you can’t take reference photos of; for example, something futuristic, some inner workings of a machine or animal, or even something fictional.

Your portfolio is your advertisement of your work. It highlights your skill and talent, as well as your problem-solving abilities, so have some fun with it. Just remember to include enough of the basics to satisfy the employer. If you’re not sure what to include, here’s some advice.

What to Include in Your Portfolio

I’m assuming that you want a job in the games industry (or a related industry) due to the title of the book, so I’ll base my advice on that assumption. When deciding what people look for when looking at portfolios, I asked a number of industry professionals what they look for. Here are a few things that came up a number of times:

• General artistic ability and command over traditional art principles (drawing and sketching, especially)

• Creative ability

• Strong original ideas

• Controlled and manageable topology and good UV layout

• Attention to detail and good observational skills (including technical details: naming conventions, pivot points, file formats, and so on)

• Good variety of work

The bottom line is to include only your very best work. If you have only five good pieces of work, then that’s all that should be in your portfolio. Padding your portfolio out with everything you have ever done not only reduces the overall quality of your portfolio but also advertises every single mistake you’ve ever made—not what you want to be doing. So, be strict and include only work that you believe to be flawless. Ask yourself, “Is this the best I can do, or are there any small improvements that I can make?” If there are, do them; it’s really important not to rush getting this together. A rushed portfolio can hold you back for many years. If you’ve included only your very best work so far, you may have only a few renders. As you flick through them, the small number of pieces may be the catalyst you need to buckle down and produce some more work. If not, it should be. If your portfolio is brimming with everything you’ve ever done, you won’t feel the same sense of urgency, so try to be aware of what you really have and what you need to do about improving it.

How do you decide what to include? Well, it all depends on the job you want. If all you want to do is model cars and other vehicles, then your portfolio should include a lot of good examples of that—one or two just isn’t enough. However, if you’re happy to do anything, then you’ll need to have a good variety of work. If you’re not sure what position you’d like to apply for, here are a few of the more common roles:

• 3D artist (does a bit of everything). This tends to be a more junior role.

• Vehicle artist (depending on the company, this can cover aircraft, military, cars, trains, and sci-fi).

• Character artist (these range from photorealistic, real world, cartoon, alien). This role can include weighting and rigging, as well as modeling and texturing.

• Environmental or level artist (real world, alien, cartoon, fictional).

• UI (User Interface artist: the selection screens you navigate between game levels).

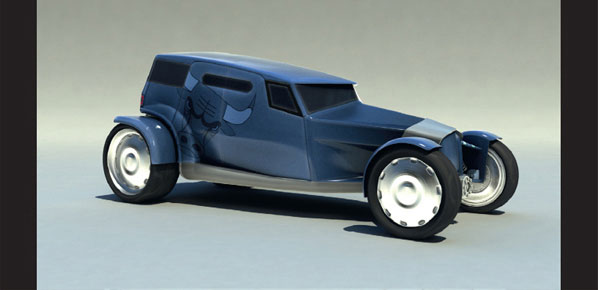

If you’re still not sure whether you want to specialize in any of the specific roles, keep everything generic at this point and do a bit of everything. Remember that originality is king here. You should create brand new conceptual forms if it allows you to flex your artistic muscles. I would much rather see a beautifully dirty and damaged vehicle for an imaginary sci-fi scene than yet another shiny Ferrari.

Ask for help if you’re not sure what your best work is. Luckily, there are lots of forums and galleries to post your work for your fellow artists to critique for you. Two of the most popular are www.deviantart.com and www.cgsociety.org

Some of the best artists in the industry post work on these Web sites, so brace yourself: this is who you’re competing with for work. Also, some of the best artists will routinely comment on your work or works in progress and offer valuable advice, which you’d struggle to get anywhere else—and the best thing is that it’s free advice.

Let’s move on to the more difficult question: what you shouldn’t include.

First and foremost, don’t include any sloppy work (unmapped polygons, stretched UVs, holes in geometry) because the mistakes will stand out from a mile away, and if you haven’t spotted such errors in your portfolio, then the reviewer will wonder what your mistakes will be like from day to day and you’ll probably be rejected.

Don’t include old work. For some reason, a lot of artists feel the need to sign and date their work, especially life drawing. If I see a date on a portfolio piece that’s more than a few years old, it makes me wonder, “What have they been doing recently?” If all the work is old, it puts me off. If you must include old work, make sure you remove any dates, or better still, don’t add them in the first place. Again, if all your work is too old, you will most probably be rejected.

Unfinished work should not be included, unless it’s your latest piece and it’s looking really good. I love it when an artist comes for an interview and shows me a piece of work that he has been working on specifically for Evolution Studios or one of the projects we’re developing. It’s great when a piece of work has been created just for the interview.

Artists do this a lot if there are gaps in their portfolio, when the work they have been doing is a different style or subject matter than the company or role they are applying for, to prove that they can do the job or even to show how much they want the job. If you do try something like this, casually drop it in at the end, saying something like, “And there’s this, which I was working on last night/week while preparing for today; it’s not finished, but …” (and then point out what you need to do to round it off). Obviously, only do this with work that is close to completion; otherwise, it will have a negative effect.

I spoke to some of my lead artist contacts in other companies about what they really don’t want to see in interviews. Here are some of their responses:

• Clichés (spaceships, Amazonian beauties, churches)

• Sloppy work (unmapped polygons, stretched UVs, poor quality)

• Unfinished work

• Scenes or exercises from books or (worse) from the 3ds Max tutorials

Overall, get as many people to look at your work as you can and listen to what they say to you. If you really like a piece but no one else does, drop it from your portfolio. By all means, keep it in a personal portfolio but don’t send it off to companies or take it to the interview.

One very important point to note is that you should not send original pieces of work under any circumstances—that is, your only hard copy of something you’ve drawn. These will not be returned to you, and you’ll lose them forever.

Now that you have an idea of what you want to do, you have to produce the work, or, if you already have it, you get to organize it.

If you feel that you might not have enough good work in your portfolio, you’ll need to plan what you need to do. It’s really important that you make a plan and stick to it. Some people create lists and work through them from top to bottom, but I prefer to use S.M.A.R.T goals. S.M.A.R.T stands for Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, and Timed. For example, if I’m applying for a new role, I might identify four new pieces that I need to produce for my portfolio, aimed at this new role. Here’s how I work out what my goals should be:

• Specific: I want to create four new pieces of work similar to (for example) my first portfolio page.

• Measurable: I identify the target quality from an existing portfolio piece. I then need to list everything I need to model, texture, compose, light, and render in the scene to hit this level of quality.

• Achievable: I take each set of time estimates for the four pieces of work that I intend to build and add rough estimates for each task, in hours. I then add all the estimates for each piece of work and see roughly how long it will take me to make all of them. Once I have this total, I can compare it to the total amount of time that I think I can spend on this work (maybe five hours a day, for example). Comparing these estimates shows me how much work I have to do and how long I have to do it in.

• Realistic: If the total of amount of work is less than the time I have to do it in, it’s a realistic goal. If it is slightly more, I may decide that if it all goes well, I can probably still do it, so it’s still fairly realistic. If the amount of work to do is far more than the amount of time you have, it’s an unrealistic goal and you should probably reconsider the amount of work.

• Timed: The closing date for applicants for the new role is (in this example) six weeks away, so to be sure I make it on time, I’ll plan out four weeks of work.

For this example, if I think each piece will take me approximately two weeks of work, then it’s obvious that I don’t have the time to do the four pieces I wanted to. In this case, I’ll opt for doing two of the pieces or re-plan the whole lot using a simpler piece of work as the quality bar.

This technique is extremely important when planning any work. Breaking down the tasks into smaller actions makes it easier to estimate accurately, which is very important for hitting deadlines, and also really useful for pricing freelance work as a contractor. To find out more about SMART goals and other planning techniques, try an Internet search—there are plenty of resources that go into planning in a lot more detail.

Now that you have your work, let’s organize it.

If you’re sending your work in to studios via e-mail or disc or if you’re compiling a printed portfolio, you must put your very best work first. In a lot of cases, a reviewer might look only at the first couple of pieces, so you have to blow them away with the very first piece. If you don’t, you’ll be in the trash—it’s as simple as that. You can organize your work as simply as a set of images, or a movie, but keep it simple. Finding and downloading strange codecs to view someone’s work really puts me off. A lot of people present their Web site portfolio, but clearly labeled folders of JPEGs work just as well.

This is how it works in some companies. A well-known developing company that makes great games and is advertising for staff might get 10 or more show reels or portfolios a day from independent applicants (the number can be even higher if recruitment agencies are involved). If the Art Manager or Recruiter looks at these once a week, they’ll have more than 50 show reels to look through; if they’re really busy, as most are, and do this only once a month … well you can do the math.

Whenever I’m faced with such a task, I know that I can spend only a small amount of time on each. If the first few images are well below the standard that we require, I’ll make a note “thanks, but no thanks” and move onto the next one. However, if the first few images are good, I’ll look a lot further through the portfolio, even if I see a few poor pieces of work, just to make sure that I’m not making a mistake or missing out on finding a good candidate. Often slightly junior members of the team are tasked to filter the applicants first. This may improve your chances if your first few pieces aren’t the best, but don’t risk it.

As well as putting a few of your best pieces at the start of the portfolio or show reel, you’ll need to put some of your best at the end. This will leave the recruiter with a good feeling about your work, improving your chances. I prefer to use fully rendered scenes containing lots of models for the start and end of my portfolio and then focus on individual assets in the middle. I often include wireframes and texture pages as half of the portfolio, so that it is clear how efficiently the models are built and rendered. This is just my preference—have a look at some online portfolios and try to work out why the artist has organized them the way they have.

Final Presentation of Your Portfolio

Once you’ve produced and organized the work, you need to present it, as well as you can. If you are sending in a show reel on disc, it must be in a box, with a cover, and the disc should be either printed or clearly labeled. Both the cover and disc should have your name, your contact details (e-mail and phone number), and also your Web site address. If you are taking in a paper portfolio to show, it should be in a clean binder of a suitable size for your work. I always use two matching leather portfolios for interviews. One is 17 3 220 (A2) with all my illustration, life drawing, pastel, charcoal, and painting, and the other is 11 3 170 (A3) and has all my 3D modeling shown as full-color renders. The smaller portfolio sometimes has magazine scans of articles and high review scores of the games I’ve worked on, depending on the role I was applying for. If you’re sending a demo reel, always remember to name your files properly—for example, AndrewGahan001.jpg, so that your work can be easily identified if it gets mixed up with someone else’s.

If you are scanning or copying work to include in your portfolio, remember to do everything in color. Even pencil drawings should be scanned or photocopied in color, as all the gray tones will be lost if you just use the black-and-white settings.

Now you have your portfolio sorted out, go ahead, and apply for that job.

I recommend that you look for your first (or next) job in these two main ways. The first, and the one I recommend the most, is to apply directly to companies that are hiring. To do this, look at the relevant magazines for your country (or the country you want to work in) and browse the advertisements from the companies looking for staff. In the United Kingdom, one of the best for this is Edge magazine, which is readily available in newsagents. You can also try looking on the Web sites for companies that you’d like to work for—often, there are positions advertised that have not been in the press yet, which might get you a slight head start on the position. There are also a lot of advertisements on various Web sites such as http://www.gamasutra.com and http://www.gamesindustry.biz; just search for “games industry 1jobs” in any major search engine, and you’ll find lots of positions advertised.

This leads me to the second method of finding out who’s hiring and the approach to take if your direct applications don’t get you the results that you want. Again, look through the relevant trade magazines or Internet search engines, but this time, concentrate on all the recruitment agencies. You will probably find these a lot easier to find than the actual companies. Browse through their listings. If there is something specific that you like the look of, drop them a line or apply direct through the Web site. If there isn’t, send an e-mail with the sort of position you’re looking for.

You’ll find that the second method might get you more responses, but possibly not be for the exact job you want. The recruitment agencies will often fire off your CV and show reel to every company on their books and get you lots of interviews. On the other hand, you might end up in a pile of other artists while the agency does all the hard work to place the more senior jobs. Remember, interviews cost money to attend, so take care how many you agree to attend, and if you are invited to one, ask if they’ll pay your expenses. In a lot of cases, they will.

The recruitment agencies work on commission and they will charge from 10% up to 30% of your starting salary to the company hiring you. For this reason alone, a lot of companies will not use them, so do your research and find out which companies do.

The most important thing you need to do with recruitment agencies is to keep calling them every week and ask for an update. If you don’t, you might get lost in paperwork.

Finally, if you’re going to start applying, you’re going to need a resume or curriculum vitae.

Resume or Curriculum Vitae and Cover Letter

Every good job application should come with a cover letter, a resume, or curriculum vitae (CV) and a show reel or demo disc. Let’s look at them in a little more detail.

A Cover Letter

The cover letter is your way of introducing yourself to the company and should explain why you want this particular job. It should give the employer some insight into your desire and your personality. It should be no more than one page long and should describe how you are qualified for the position. This is a good opportunity to make an impression and maybe stand out from the crowd. This is also a good opportunity to make a bad impression, so be careful what you write. A letter that lacks specifics about the position or company that you’re applying to will look like a mass mailing and will show lack of effort and thought. Always use a spell-checker on all your text; spelling mistakes show that you have poor attention to detail—this really does matter. Also ask someone you trust to proofread your letter, as they may see grammatical errors that you missed, which must be corrected.

Resume/CV

A resume or curriculum vitae (CV) is a list of your skills, experience, interests, and successes; nothing more. It should not contain page after page of details about your hobbies or spare time, and it should not be used as an opportunity to hype every single thing you’ve ever done. A good resume will be easy to read and no more than two pages (maybe three if you have had a lot of relevant experience). It should have lots of open space and be presented in a clear, easy-to-read font such as 12-point Arial. You should print it on good-quality paper and put it in a matching envelope. Recruitment agencies routinely take personal information off CVs when they send them out; this often messes up the formatting, making them difficult to read. Obviously, if you apply for positions personally, you get full control over how you are presented. Also, it’s important not to go mad with jazzy paper and gimmicks—we’ve seen them all before and are not usually impressed by anything that is supposed to shock or amaze us.

You can use the following checklist to produce a good CV directly:

• Contact information (phone numbers, e-mail address, and mailing address)

• Objective (the exact position to which you are applying)

• Experience (employment dates, job titles, and brief descriptions of responsibilities)

• Skills (Maya, 3ds Max, Photoshop, Illustrator, and so on, including version numbers)

• Education (degrees, certifications, and additional training)

• Other relevant skills (related skills, personal successes)

There is also a mountain of free advice on the Internet for creating good CVs and resumes. Just search for “CV or resume” and you’ll find a lot more detailed advice.

One important point about your contact information is that if you are currently using an e-mail address that you set up in college that is something like biggy69@hotmail or sexyboy1980@yahoo, then you’ll need to change it to something more professional. You should definitely have your own Web site when looking for a job, even if it’s just a one-page resume that you’re putting online. It is so cheap to create and maintain a Web site these days that it’s pretty much a no-brainer. In addition to letting you circulate your name and qualifications worldwide, it’s also a permanent e-mail address for life, which is important: you’re permanently reachable through [email protected] instead of having to rely on a hotmail address. It comes off as very professional and shows good thought and consideration.

The best thing to do is to register a Web domain that is your name or similar and generate a new e-mail address using the new domain. You should also get a Web site hosted on this domain showcasing your best work (your portfolio) and any new work that you complete. There are loads of cheap Web hosting organizations (I use http://www.streamline.net), and if you’re not a Web developer or don’t know anyone who is, you can get cheap Web sites done for you by using http://www.elance.com or by getting your local Web developer to put together a single-page site. If you do put your own Web site together, always remember to use images to show your e-mail address or contact number—this will cut down on the amount of spam you get from bots searching your site for contact information.

There is a wealth of advice available about interviews, techniques, and what you should and shouldn’t do, but here are a few key points directed to the creative industry in general, and more specifically, the games industry:

• Preparation: Preparation is extremely important and will give you some confidence in the interview. Know the company you are applying to. Find out what games they’ve made, who the key staff are, and especially, what they are working on now. If you can’t find out what they are currently working on, the project must be unannounced, which gives you a great question in the interview.

• Arrive on time: You’re going to meet some very busy people and they will not be amused if you’re late. If you have to be late, make sure you that telephone in as soon as you know and give them a realistic time when you’re going to arrive. This will give them time to reschedule. If you’re late and you don’t call, you may miss your slot completely, and it will be a wasted journey. Also, don’t arrive too early. I’ve had applicants turn up one and a half hours early, which really put me on the spot. Do I leave them sitting in reception for 90 minutes for a receptionist to look after or do I reschedule half my day? Either way it is a hassle that you don’t want to cause anyone.

• First impressions are lasting impressions: You will never get a second chance to make a first impression, so try to get it right. First, smile when you are introduced; it will get you off to a good start. A firm handshake is next—not a vice-like grip or a clammy wet lettuce, just short and firm. If you’re really nervous and your hands are sweating, ask the receptionist where the restrooms are and freshen up before you meet anyone. Dress is also important. You’ll need to look professional. Wear a nice long-sleeved shirt, some smart or casual trousers, and some clean shoes. As it’s the creative industry, most people will be very casual, but don’t assume that the people interviewing you will be. They are likely to be fairly senior staff and may well be very tailored. You can dress down once you have the job. Finally, use eye contact, but don’t glare. Keeping eye contact will make you look more confident than you may feel. If two people are interviewing you, it’s easier, as you can switch between them. If you talk to people while looking away, they might think that you lack confidence or even interest.

• Listen: I realize that this sounds obvious, but it’s really important to listen to the questions you are being asked before you answer them. Wait until the interviewer has finished speaking and then answer that question only, without waffling. Your answers should probably be only a couple of minutes long. Remember not to talk too much, too.

• Stay positive: Sometimes an interview feels like it’s not going well, but as you can’t be sure, you need to stay positive and enthusiastic. It’s okay if you’re asked a particularly difficult question and you don’t answer it very well; just move on and focus on your successes and all the great work in your portfolio.

• Ask questions: If you can get a couple of good questions in early, without coming across as pushy, you will be able to tailor some of your responses to suit what the interviewer is looking for. Here are two good examples of questions you could ask:

• What would be my responsibilities if I were to get the position?

• What qualities are you looking for in the ideal candidate?

• Try to keep a good dialogue going, as well as answering the questions, and try to ask some of your own—don’t just leave them to the end.

• Be honest: It’s very important to be honest in interviews, as well as on CVs. A lot of companies check references and career histories to make sure that candidates have actually done what they say they have. A friend of mine told me that he did a background check on someone he had just interviewed and discovered that he’s lied about a role on his CV. Although the candidate was very talented and would have got the job without the lie, my friend could not trust him and didn’t make him any offers. It’s a common myth that most people lie on their CVs; they don’t and you shouldn’t either. If you lack experience, then your work must stand out on its own. If it doesn’t, keep working hard, posting on forums, and learning as much as you can. What we do isn’t rocket science, and if you persevere, you’ll get your break into the industry.

There are also a number of things that you shouldn’t do, but (skipping the obvious), here are a few essentials:

• Don’t disrespect previous employers, tutors, or colleagues: One of the best ways of talking yourself out of a job is by saying negative things about previous employers, professors, or colleagues. It won’t help you in any way if you do it—so don’t.

• Salary and holidays: This question comes up more than any other when I ask junior artists if they have any questions for me. Obviously, salary and holidays are important, but don’t bring it up unless they do. Besides, you can always call the HR representative of the company or whoever booked the interview once you know that they like you or in the second interview.

• Have some questions prepared: It is not a good sign when I ask a candidate if he or she has any other questions, and the candidate says, “No.” If you’ve prepared for the interview, which you definitely should have, you should be able to ask the interviewer a series of good questions about the company, the direction it’s going in, expansion, new projects, or whatever. If you have nothing to ask, it shows that you haven’t done your homework, you’re not interested enough in the job, and that you’re wasting everyone’s time.

• Don’t forget to follow up: Even if you think that you made a complete disaster of the interview, don’t forget to follow up with a written note thanking everyone for the interview and reiterating your interest in the position and the company.

If after doing all of this, you are still rejected, don’t take it too personally and don’t see it as failure. It’s just a result; not the result you were looking for, but a result that you can learn from. I have had artists apply to me more than once, and in some cases, I have hired them the second time around. There are a number of reasons why you weren’t picked for the role, but if you keep improving and working as hard as you can, you’ll get there.

Congratulations on completing the book! Good luck, and don’t forget to check out more advice and tutorials on www.3d-for-games.com, and be sure to use the forum; it is a wealth of valuable information for amateurs and professionals alike.