Developing a Short Animated Film with Aubry Mintz

I have found a system for developing animated films after 13 years working with professional and student filmmakers to create short, one- to five-minute ideas that they are able to produce within a year. I also apply this system to my own work, and will use my current film Countin’ on Sheep as a case study to show how to take a short film from idea to production. I hope you enjoy this chapter, and if you decide to make a film, I trust this can be of some use to you.

Countin’ on Sheep Synopsis

This film takes place in Arkansas at the end of the 1930s Dustbowl and involves Zee, a six-year-old boy who has lost his lower bunk bed to his visiting grandmother. He has no choice but to climb all the way up to the top bunk. But Zee has an extreme fear of heights so he resorts to sleeping on a chair. Unable to get comfortable, he begins counting sheep, but there is one sheep that is also afraid of heights and won’t jump the fence.

This animated short film is about overcoming fears by successfully confronting obstacles that stand in the way of our goals.

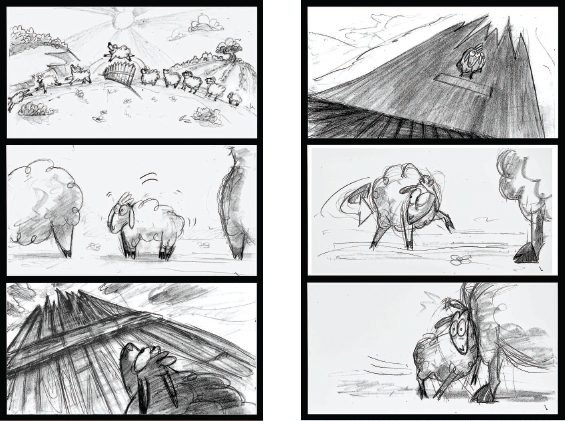

Images from Countin’ on Sheep, Rough Drawings Aubry Mintz, Clean Drawings Dori Littell-Herrick, Color Frank Lima. Copyright Aubry Mintz, all rights reserved.

Know What You are Going to Write about

Films take time. Films actually take longer than that; they take an enormous amount of time. Since you are going to live with this film for at least a year or two, it is important to do something you enjoy and believe in. You don’t want to be a year or so into a project and realize you don’t want to do it anymore. So, it is a good approach to develop several ideas when you begin this process to help you find the best one for you.

Beware of choosing an idea too quickly. I recommend that you carry a small notebook as you start to come up with film ideas. Carry this notebook with you everywhere. This will allow your brain to come up with new ideas constantly. Much like a computer, your brain will also process in the background while you are doing other things like eating or sleeping. I also recommend placing this notebook by your bedside; this way, you might inspire dreams that you can jot down as soon as you wake up.

This first stage is not about latching on to the perfect film idea, it is more about allowing your brain to start generating as many thoughts as possible. So don’t hold back. Have some fun!

Finding Your Idea

At some point you can read through your notebook of ideas. You may find that the first ideas that come out of your head are the most typical or cliché ideas. I actually encourage students to go for the cliché at the start to get it out of their systems. This will allow you to develop ideas that already have preconceptions built in.

I call these types of ideas “universal knowledge.” They are ideas that don’t require too much set up (i.e., two naked people in the forest looking at an apple like Adam and Eve). However it is important to remember that when writing stories we have read before, you will need to unfold it in a new way to keep the audience engaged. The challenge is how to tell a story in a fresh and interesting way.

At some point you might start expanding on a new take of an old idea or it might even evolve to a unique idea. Allow the idea process to occur naturally without forcing it. This will let you come up with something that truly represents you.

I have heard many times that “no idea is original.” It is how we individually choose to twist and turn it that makes it our own. As Bill Kroyer says: “At the end of the day you want to try and make something that’s wholly your statement. If you do that it will be unique and hopefully it will be something that people respond to.”

Finding Your Seed Idea

Once your brain is set in motion, it will most likely produce several quick “seed ideas.” (For Sheep the seed idea was “a counting sheep that would not jump over the fence.”) Jot down these seed ideas into your notebook.

Once you have several “seed ideas,” start sharing them with someone. Writing your ideas down is one thing, but they take on a different meaning when speaking them aloud.

When I am listening to ideas, I find that the good ones spark the imagination. If I find myself wanting to know “what happens next,” then it is probably an idea worth developing. That’s what you should be listening for.

Brainstorming is an ideal way to get a bunch of creative people together and hash out story ideas. They do it all the time in the studio system, why shouldn’t we? You never know where an idea will come from. The group discussion should help unfold and refine your idea. You will have many different opinions, some will naysay parts that don’t fit, and others will add scenes or gags that may work perfectly. A brainstorming session is a great way to unpeel the layers and uncover the story that begs to be told.

Although it is your idea, I would suggest allowing other people to speak. This is a good time for you to sit back and let the group-mind brainstorm. If the conversation slows down, you can help pick it back up, but otherwise, get out your notebook and write down what the group is saying. In the end, it’s your film. You need to choose only the notes that you want to incorporate. So, no pressure; let them have at it!

Countin’ on Sheep: Case Study #1

I came up with the idea for Sheep in a dream, or more like the lack of a dream. My goal was to make a simple film that would take less than a year to finish. Sounds easy enough, right?

I found it so difficult to write such “a simple film” that I couldn’t sleep. I became exhausted from days of racking my brain. I lay in bed at night, fully awake, as ideas came in and out of my head with no substance, none worth jotting down. I was tired, but restless, and I needed something to get my brain to calm down. So, believe it or not I started counting sheep.

1 … 2 … 3 … 4 … Then, all of a sudden, the fifth one wasn’t jumping. He was just standing there, staring at me. No matter how I tried to get him to move, he would disregard my imaginative direction and do everything but jump. He was smelling the flowers, sleeping, reading, but not jumping.

Images of Countin’ on Sheep seed idea. Copyright Aubry Mintz, all rights reserved.

I couldn’t sleep. My mind was going completely haywire. Or was it? Then, lightning struck.

My eyes popped open. I bolted out of bed and headed straight for my drawing board. I spent the next 12 hours storyboarding an idea for a short film about a counting sheep that would not jump over the fence. This became my seed idea.

Research Grows the Seed Idea

Once I find a seed idea I will then spend time researching the theme. The more research I do, the more I can put myself into the story, time period, character’s mind, etc. My hope is that the story will have an authenticity to it, given that I have worked so hard getting to know my characters and their environment.

Images for Countin’ on Sheep based on research of 1930s poster designs, Digital Paintings Jarvis Taylor, Art Direction Doug Post. Copyright Aubry Mintz, all rights reserved.

For Sheep, I knew I wanted the film to take place in a rural, farm area. Through research, I learned more about the Dustbowl of the 1930s and was blown away by the imagery and stories from this devastating decade.

I am very fortunate to work at California State University Long Beach that has an excellent research staff at the library. The librarians thought of things I would never have. The stacks of research materials were abundant, such as, interesting advertisements in periodicals from the time period, fruit crate labels from farms of the era, Dorothea Lange prints, Woody Guthrie songs and much more. I spent the better part of two weeks inspiring and informing my ideas with a richer understanding of the Dustbowl era.

In the stacks of books, there was one that really struck a chord. It was a compilation of poems written by children from that era. I remember one poem about a child who was given 30 cents to buy groceries to feed her family for a week. But when she got to the store, all she could think about was the candy she could get for the money in her pocket.

Images from Countin’ on Sheep, Rough Drawings Aubry Mintz, Layout Lennie Graves and George Fleming, Clean Drawings Dori Littell-Herrick and David Coyne, Color Frank Lima, Lynn Barzola. Jesse McClurg, Whitney Brown, Jamie Ludovise. Copyright Aubry Mintz, all rights reserved.

This dramatically changed the way I thought about Zee, the boy in my film, and the decisions he makes. This poem helped me realize that the main character in my film (a six-year-old boy) would not be as concerned with the Dustbowl as he would be with regular child issues. Zee was more worried about Gramma taking over his bottom bunk and leaving him to climb to the top bunk.

While the Dustbowl is a very important element of my film, I did not want it to overshadow the main story. Instead, it became a layer of storytelling that I utilized to help portray the mood and era in which the story takes place.

For me, the library continues to be a great source and gives me more options than Google. I find Google’s selections are sometimes limited and repetitive.

Once you have a strong seed idea, you can begin selecting books that call out to you. Explore these books page by page.

Don’t rush this stage, as it will allow you to react to images and words that attract you. You do not need a particular intention. Just allow your brain and eyes to soak it all up. Flip through pages and get inspired!

Preproduction

Once you have what you feel is a solid idea, spend some time in preproduction to visualize your story.

Start with a few passes at a thumbnail storyboard (small rough quick sketches). This will help you produce a quick visual idea of what takes place in your story. If you focus on the main beats of the story and stage it in a straightforward manner (rather than worrying about a variety of angles or complex camera moves) this will allow you to narrow in on the story you are trying to tell.

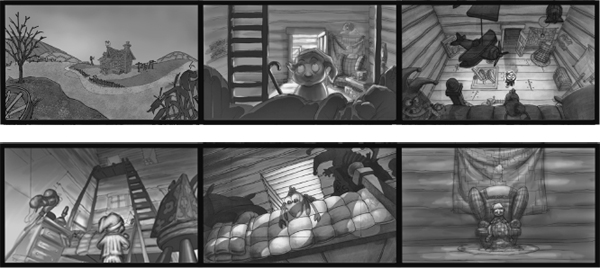

Images from Countin’ on Sheep, Art Direction Notes Doug Post and Lennie Graves. Copyright Aubry Mintz, all rights reserved.

Often, film productions will hire visual development artists to inspire the directors while the script is developing. It is a good idea to create a few concept art pieces to set a tone for what your film might look like.

When I am at this stage, for inspiration, I will surround myself with reference materials of the time period (clothing, environment, photos from the era, etc.). I print the images and paste them on boards and literally surround my peripheral with visual reference. This allows my eyes to search the boards until I see an object, person or environment that inspires me to draw. Sometimes I’ll focus on something as small as a rock or a character’s boot, at other times it’s an entire scene. I am not trying to make any final decisions; rather, I am searching to figure out what this film might look like. Basically, I am brainstorming with artwork.

Images from Countin’ on Sheep, Rough Drawings Aubry Mintz, Drawings of Truck Cuyler Smith, Gramma Design Dori Littell-Herrick, Color Doug Post. Copyright Aubry Mintz, all rights reserved.

At the point when you have enough images, references, rough storyboards and designs, you are now ready to really focus on what your movie is about. You could spend countless hours, days or even months developing story ideas that end up being rearranged from one story to another but seem to continually change. This can happen when you don’t know the story you really want to tell.

The best way to combat this is to find the premise of your story. Author Lajos Egri writes an excellent chapter on premise in his book The Art of Dramatic Writing. I recommend this as a must to all of you searching to tell a story.

The important thing is to try and refine your story down to a sentence or two. The premise statement should have these three elements: character, conflict and resolution.

For my film, Sheep, the premise might be:

- Taking the first step (character) leads to (conflict) overcoming your fears (resolution).

- Not taking a chance leads to stagnancy.

- Fears can’t be overcome until you face them.

- An acrophobic sheep must finally face his fears and jump over the fence or he will be stuck.

All of these might work, but I settled on the following for now: You can only overcome your fears (character) by facing them (conflict) on your own. No one can jump the fence or climb for you (resolution).

You want to try and define your film in the simplest way possible. A few sentences sound easy to write, but this is actually difficult. Take your time and try to whittle your idea down to a clear premise.

Once you find your premise, it is a good idea to step back and think about your statement and make sure that this really is the story you wish to tell. Lock it down and you are ready to move on.

Using Your Premise

Once I have my premise statement, I am then able to go through my images and decide what works best to tell this particular story. There may be some killer images that I fell in love with, but if they were not supporting my story then I would need to save them for another film. You need to focus on the premise. Here are some examples of images that did not make the cut into my film idea.

Images from Countin’ on Sheep, Digital Painting Kristen Houser, Layout Lennie Graves, Art Direction Doug Post. Copyright Aubry Mintz, all rights reserved.

Images from Countin’ on Sheep, Concept Art Ryan Richards. Copyright Aubry Mintz, all rights reserved.

If I’m clear about the story I am trying to tell, all of the shots must have a purpose. With this in mind, I review my storyboard and take out the scenes that don’t push the story forward.

Sometimes you see films that have shots or camera moves that look really neat yet don’t necessarily help tell the story. In Francois Truffaut’s interview with famous film director Alfred Hitchcock (p. 47, Hitchcock, Simon & Schuster, 1983) they discuss a film where the camera shot is from inside a refrigerator and question the relevance of this. Hitchcock goes on to say:

I am against virtuosity for its own sake. Technique should enrich the action. One doesn’t set the camera at a certain angle just because the cameraman happens to be enthusiastic about that spot. The only thing that matters is whether the installation of the camera at a given angle is going to give the scene its maximum impact. The beauty of image and movement, the rhythm and the effects —everything must be subordinated to the purpose.

Hitchcock places importance on getting the right emotion out of the scene rather than choosing camera angles that just look interesting.

One of my professors from college and co-author of this book, Ellen Besen, once told me that everything in a film is “information” and that you want to try and do your best not to have any “misinformation” on any frame of your film. What she meant by that was to be clear about everything you are communicating to your audience. Every frame of your film counts and it is very important that all of the elements in your film are there for a reason.

Once you have the overall arc of your story, with a clear premise and have worked out your main story beats, you can then break down the beats into sequences. At this point, ideas gel and scattered fragments fall into place.

Based on the overall arc of the story, think about where you are in each sequence. Are you setting up a character? Building to the climax? And how are you communicating this? Can you say it stronger with a different camera angle? How about the lighting, color, sound, dialogue, etc.?

Images from Countin’ on Sheep, Storyboards Aubry Mintz, Lighting Lennie Graves, Erik Caines and Cuyler Smith. Copyright Aubry Mintz, all rights reserved.

Every stage of animation or film production allows us to add another deeper level of storytelling into our films. If we know the story we are telling and plan it well enough we can make a strong impact on the audience.

The next example shows how using each of these elements strengthens the power of the scene.

Countin’ On Sheep: Case Study #2

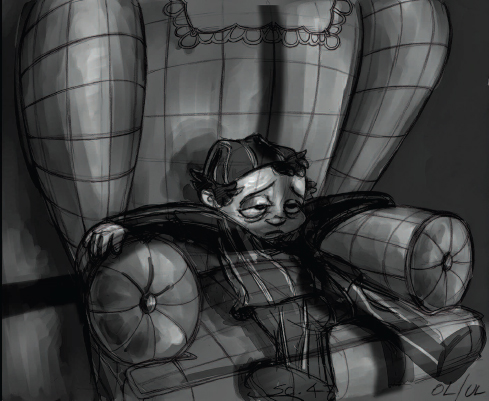

To help illustrate, in this sequence, Zee is stuck in his chair. He is exhausted from lack of sleep and his fear will not allow him to climb to the top of his bunk bed.

To strengthen this idea I played with Zee’s posing and drew him as sinking deep into the chair, almost as if he was stuck.

There are strong shadows across his arms and legs appearing to hold him down.

Image from Countin’ on Sheep, Digital Painting Jarvis Taylor, Layout Lennie Graves, Character Aubry Mintz, Art Direction Doug Post. Copyright Aubry Mintz, all rights reserved.

Image from Countin’ on Sheep, Storyboard Aubry Mintz. Copyright Aubry Mintz, all rights reserved.

I added special effects of rain and lightning outside the window to create flashes of light with loud claps of thunder.

The color will be cold and dark, making it even harder to imagine getting up.

In terms of the layout, I placed Zee and the bed at opposite sides of the room showing how far he would have to walk. I also exaggerated the size of the bed illustrating how high he would have to climb to the top.

Image from Countin’ on Sheep, Layout Lennie Graves, Character Aubry Mintz, Digital Painting Kristen Houser, Art Direction Doug Post. Copyright Aubry Mintz, all rights reserved.

The music that was once light and bouncy has held on the last chord and fades into silence, giving Zee nothing but himself to listen to and forcing him to make a decision.

When Zee finally does move, I show Zee slightly out of focus. As he walks toward us, I bring him more in focus. I show his growing confidence as he gains clarity concerning what he has to do.

It is these kinds of decisions that can strengthen the scene and give the audience more contexts to understand what the character is going through emotionally. You probably don’t want to do this in every sequence of your film so that you can build the dramatic effect toward the climax. And as I mentioned, these sequences should evolve out of the story rather than utilize them only for dramatic effect. When it all works together you have the opportunity to really make an impact, and everything is working to strengthen the story.

Finding the Motivation for Your Character

Until you understand your character’s motivation in the story you cannot make your character move. Every aspect of the character should be motivated by what the character wants and is thinking.

In order to understand your character better, a good exercise is to write a few pages about who your character is. In Zach Schwartz’s book And Then What Happened, he discusses finding the three dimensions of your character to help with this. They are:

- Physiology: What do they look like (short, tall, heavy, skinny, skin color etc.)?

- Sociology: Where does your character come from (neighborhood they grew up in, how they were treated by their parents, etc.)?

- Psychology: How does your character think (are they positive and laugh a lot? Do they have a hot temper? etc.)?

I recommend writing at least a page on each category. You do not have to create an entire novella for a back-story, but it is good to concentrate on your character, as it will help you understand the decisions he/she/it will be making. You can then use the back-story to help feed into the character’s design. For example, I knew that Zee in Sheep was a six-year-old boy living on a farm during the Depression who had a fear of heights. So, I drew him with messy hair, dressed in an old T-shirt probably that once belonged to his father, and created poses that showed his insecurity.

Images from Countin’ on Sheep, Character Design Aubry Mintz, Cleanup Dori Littell-Herrick and George Fleming. Copyright Aubry Mintz, all rights reserved.

With Sheep, I did not originally have a motivation for my sheep character. All I had was a seed idea about a counting sheep that would not jump over the fence. I felt this was a solid idea that most people would understand. The challenge for me was to tell this story in a fresh way. After pitching the initial storyboard it was clear that the idea needed more of a conflict rather than not being able to jump over the fence. I needed something more specific.

I was lucky that I had a small crew to work with so we started to brainstorm and came up with a solid idea that worked perfectly. We decided to make the sheep acrophobic (afraid of heights). We thought it would be a great conflict to show a sheep whose job it was to jump, but was incapable of lifting off the ground.

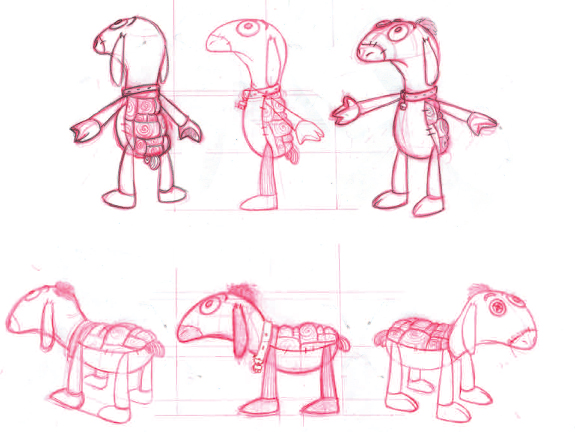

Now that we had the sheep character’s motivation, we were then able to explore his design. Instead of creating a generic counting sheep, I thought we should go back to my research. I knew that my story took place at night in a six-year-old boy’s room in a farmhouse during the Depression era. How could the sheep complement the boy and relate to the story?

This then gave me an “aha moment” as I tied it all together. What if the sheep was Zee’s doll? And what if Gramma threw the sheep doll up on the top bunk? Not only was Zee unable to climb to the top bunk because of his fear of heights, now he was alone and without his sheep doll. I had a structure for my story.

Once we had a solid structure, we were then able to start creating the sheep character design. This led us into the fantastic world of Depression-era toys and fabrics. We discovered that a farm boy, at this time, would not have a doll that was store bought but rather a doll that was made up of scraps of fabric. Therefore we made the sheep a patchwork doll. And it all started to fit together into a world that felt right.

Images from Countin’ on Sheep, Character Design Aubry Mintz. Copyright Aubry Mintz, all rights reserved.

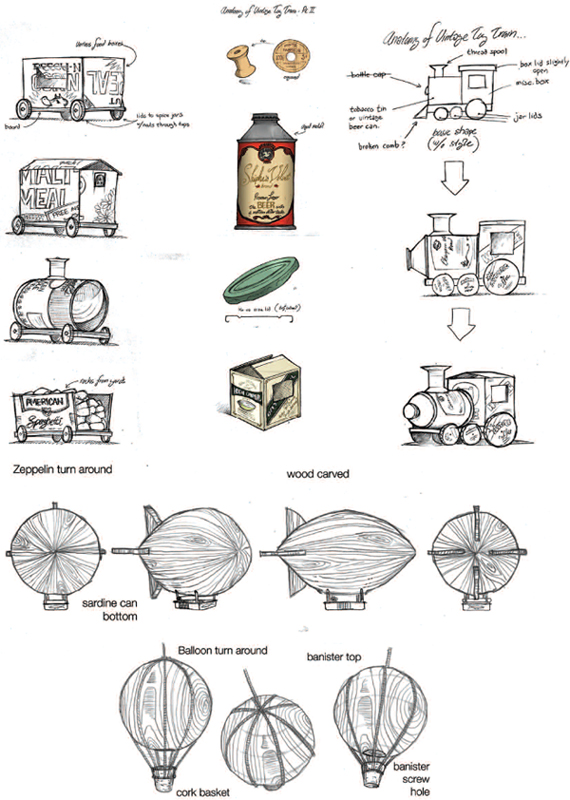

The research led us to more ideas about other handmade toys that could be in Zee’s bedroom. All of the concept artists took their turn reimaging different toy ideas for the boy’s room. The magic of collaboration (see images on p. 235).

Finding an Ending

Now that I have the story structure and the character’s motivation I could just plop on a beginning, middle and end. Right? I only wish it was that easy.

Finding a fresh ending is probably one of the hardest things I find about storytelling. It’s not just about finding a conclusion that no one has seen before, but one that logically grows out of the story you are telling. There is nothing more frustrating than becoming totally involved in a film and the character’s journey, only to be sent off in a different direction with the main character making decisions that are completely out of character.

When I was searching for an ending for my film, I tried out several versions, and you should, too.

In one version, the other counting sheep help the hero sheep off the fence but that didn’t work because the premise of my film is about the hero sheep taking his first step to overcoming his fear. Having the other sheep help meant that he was just a participant and the other sheep solved the problem for him.

Images from Countin’ on Sheep, Train Design Kevin White, Blimp and Air Balloon Design Cuyler Smith. Copyright Aubry Mintz, all rights reserved.

In another version, the sheep was knocked off the fence by a conveniently timed bird flying by. This did not work because, once again, it wasn’t the sheep’s conscious choice to jump; rather, it was an outside force that pushed him over.

I did not have my true ending until I was able to spend some time with master animator and director Eric Goldberg. He watched my film, thought for a moment, then gave me a new version with a clear, simple ending. It flowed so naturally that this idea really was the only idea that could have happened in this situation. Goldberg has years of experience and it shows with how quickly he was able to solve this problem.

What he came up with was this: The sheep appears to give up. He is assisted off the fence and walks away. This leaves Zee by himself, thus forcing him to work up the courage to finally climb the ladder. Back to the sheep, we see he was actually just gaining distance in order to make a running jump. With courage and conviction, both rise to the occasion and land in each other’s arms.

In this ending, the sheep and boy reach their goal by their own volition rather than relying on an external force.

Images from Countin’ on Sheep, Animation Aubry Mintz, Cleanup Mona Kozlowski, Color Cindy Cheng. Copyright Aubry Mintz, all rights reserved.

You’ll know when you have the right finale because it is such a clear “aha” moment. I have also seen this happen many times with my students’ films; once the right ending is found all of the pieces fall into place. Quite often, it is usually pretty straightforward, not obvious or predictable, but something that the characters would naturally do, based on the story that is being told. It is one of the hardest things to do, but once you have it, you know you have it and you are done.

Countin’ On Sheep: Case Study #3

Doug Post, the film’s art director, talks about the visual choices we made and how they supported our story.

We started with two overriding ideas that drove the visual process. First, this story needed to be told in two worlds: the boy’s “real” world and the one he imagines. Second, the Dustbowl, Depression-era setting brought particular and interesting qualities with it.

The boy’s world is a more impoverished, confined place where Zee feels trapped and afraid for most of the film. We assigned this world a traditional, hand-drawn animation process. Literally a flatter medium, we pushed this further by also giving it a palette with less value contrast and less intense colors.

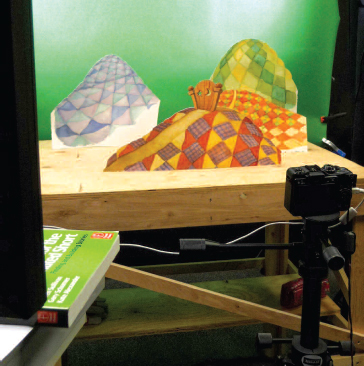

The sheep’s world of Zee’s imagination needed to be more playful and open as it reflects the boy’s desire to break out of his fear. It was decided that these scenes would be produced with a stop-motion animation process. The tangible three-dimensional quality of stop motion gives these scenes actual breathing space. Unlike the boy’s world this one has much richer, more saturated colors. Additionally where most of Zee’s scenes take place indoors, the world of his imagination, while made up of things from his room, suggests a vast landscape (see images on p. 239).

The Depression-era inspired us to give the things in this film a handmade, patched together, even layered look. There are obvious patch quilts throughout the story, but we also we gave the boy’s world a lot of subtle textural layers taken from sources like corrugated metal and newspapers of the day. We were going for a worn, dusty and gritty feeling. In the dream world because of the stop-motion process things are actually handmade for the film and the occasional fingerprint only adds to the intent.

Image from Countin’ on Sheep, Stop Motion Set

Once the rules of the film were established we could visually weave the two worlds (and techniques) together as the boy and sheep work through, and eventually overcome their fears together.

By the end of the film Zee’s traditionally animated world is a place where he can breathe again—the rain has washed the dust away and the morning has brought a more colorful, more “three-dimensional,” and more hopeful environment.

Image from Countin’ on Sheep, Sheep Maquette Dallas Worthy

Making Music

Music can absolutely strengthen or weaken your film. It is very important to work with your composer to make sure the music complements the film. As Perry La Marca states in his interview, “The greatest contribution music can make is to help enhance the emotional experience for the viewer.”

For Sheep, I imagined the boy living on a farm, perhaps in an earlier time. I was very attracted to old time country music by the likes of Bob Willis and the Texas Playboys. Specifically the song “Time Changes Everything” rang in my head and I placed it as a temp-track on one of the first animatics. I decided that music was going to play an integral role in my film.

So in 2007 and 2008 I was fortunate to meet the members of the Arkansas band Harmony and songwriter Charley Sandage. Charley and I worked together to develop the music for the story. With Charley’s guitar and my drawing paper, we sketched and played for three days until we found our song. We decided that the music would narrate the film.

Images from Countin’ on Sheep, Concept Art Melissa Devine, Aubry Mintz, Robin Richesson, Jennifer Cotterill. Copyright Aubry Mintz, all rights reserved.

Musical Band Harmony, from left to right: Robert and Mary Gillihan, Charley Sandage and Dave Smith.

Charley Sandage, the film’s composer talks about how he developed the music for Sheep:

This was my first attempt to write music/songs for an animation project, and I was struck by what I found to be the degree of control the producer has in this medium. This may be only a layman’s misperception, but it seems to me that the animator can make deeper and subtler decisions about look, feel, interpretation, staging—every element of a production—than can the producer of any live-action film, live theater production, or documentary piece.

All of this underlines, in my view, the importance of Aubry’s wish to work so closely and collaboratively with me at such an early stage of the project. This was something of a leap of faith on both our parts, since we hadn’t met in person until the day when we sat down to start work. For good or ill, the process of shaping the music became inseparable from the process of shaping the overall project. Even when we were finally recording, Aubry and his art director were there, guiding and trimming.

Since I’m a songwriter who usually starts with a lyric and then hears the music, this project came with some easy hooks for me. The essentials of the narrative focus on “sheep” and “sleep.” Those words happen to rhyme. Zee’s sheep counting led easily to the “counting on sheep” title. Repetition in the refrain works because the narrative unfolds in stages. The verses just tell the story. The feel of the piece calls for simple, ruralness-evoking, acoustic sounds such as banjo, autoharp and mandolin in a moderate tempo.

Harmony, the trio, are gifted musical storytellers and traditional music stylists. When we took it to the little Mountain View, Ark., studio of Joe Jewell, who is also an Ozark musician, the elements flowed together. When it happens that way a writer is grateful.

In April of 2008, animation artist Lenny Graves and I took a trip to Mountain View, Ark., where we stayed four days to record the score with Charley Sandage and the band Harmony. Our research trip to Arkansas gave us more than just a great film score; it actually altered a pivotal plot point for the story.

Surrounding ourselves in the environment heightened our awareness of a small farm town in Arkansas. We breathed the same air that Zee breathed. This gave us further insight into how he might think. Reading about your research is one thing; actually experiencing it gives you a whole different appreciation.

The trip inspired us so much that we modeled the environment on the town. In fact, the design of Zee’s home is directly based on the home of the guitarist of the band. You never know where your inspiration will come from.

Image from Countin’ on Sheep, Photo of Arkansas House, Drawing of Zee’s House Lennie Graves, Clean Up George Fleming and Kevin White. Copyright Aubry Mintz, all rights reserved.

We happened to visit Arkansas in late March. Charley Sandage, the film’s music composer, constantly talked about the start of spring with the blooming of a tree called “the red bud.” He talked about it with such passion; but I was unsure as to why. When I looked in the forest all I could see were leafless branches with little red bud dots scattered throughout. Charley kept talking about a dramatic change that would soon happen and told us to “just wait and see.”

Then to my surprise, at the end of our trip, the red bud began to bloom. Overnight, the hillsides of the Ozark Mountains completely transformed and were covered in magnificent pink red bud bloom. What a sight to see!

The crew and I started thinking about how weather and the environment could play a part in this film. So we decided to use the weather as a storytelling element.

As it takes place in the Dustbowl, at the start of the film the land is covered in dirt. Then, as the climax builds, there is a thunderstorm. This creates supportive storytelling moments inside the farmhouse with shadows from lightning and loud claps of thunder.

In the end, the rain ceases which adds another layer of storytelling. Not only does Zee’s decision to climb the ladder make his fear go away, but also the rain actually signifies the ending of the drought that has affected the land for almost a decade.

So when we see the exterior of the farm again we can paint it in a new light with the freshness you would see after a rainfall. I also added the blooms of the red bud throughout to signify new growth and renewal of the land.

Images from Countin’ on Sheep, Concept Art Alina Chau. Copyright Aubry Mintz, all rights reserved.

I hope that this comes across subtly, yet emotionally, in the film. I was happy with uncovering the layers of this story and surprised that it all started with learning about a tree in Arkansas.

Managing It

Dori Littell-Herrick, the film’s co-producer talks about how to manage your film and keep yourself on schedule:

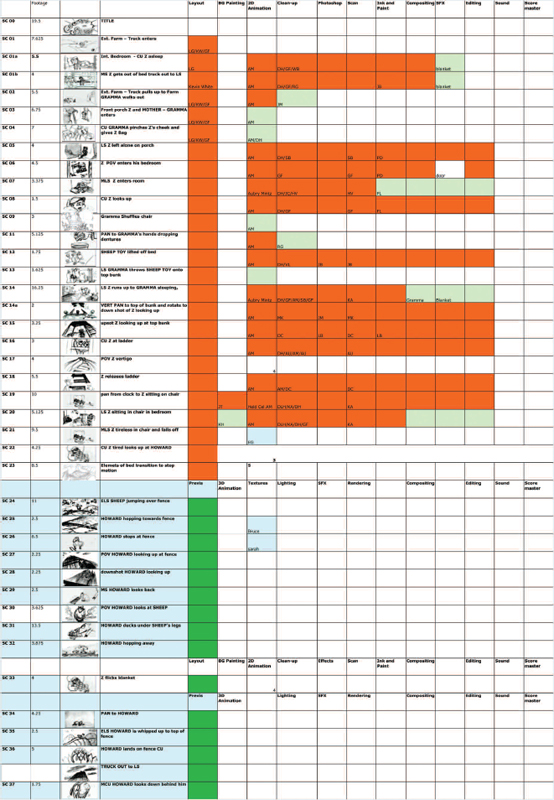

Once you have a locked animatic, the best thing you can do is create a working production schedule. To do this you need to know three things: your deadline, your pipeline, and the size of your crew. Someone else, like your school or the freelance client, will likely set the deadline. You can adjust your project to meet the deadline by simplifying the look for an easier pipeline. Knowing how long you have to finish all of the tasks will tell you if you need help.

I find my students are often unaware of how much time it takes to complete something. I suggest they write down what they do for seven days straight, Monday through Sunday. This includes when they wake up, have meals, go to classes, do homework, have social time, and finally when they sleep.

Then I ask them to count the hours left between all of their daily/weekly stuff. This is often the “aha moment” when they realize how little spare time they have. Making a film can be a full-time job! Do not make the mistake of saying, “Oh, I’ll get it done” and blindly starting a film. It is hard work; do not underestimate it.

The more you can plan ahead of time, the more you can be realistic about what type of film you can make. If you have less than 20 hours a week and want to finish this film in a year, chances are you will be making a simpler film with fewer layouts and stylized or limited animation. If you have more than 40 to 60 hours in your week then you can plan for a more complex, fully animated film. In the advertising world it is said that every project has three categories; time, money and quality but you can only choose two, you can never have all three. It is rare to have all of the money and time you need, which means you may have to compromise on quality. Don’t let that stop you from making a good film; limits lead to creative solutions.

Image from Countin’ on Sheep, Production Schedule Dori Littell-Herrick. Copyright Aubry Mintz, all rights reserved.

Unless you have a dedicated production manager, you are responsible for constant emails and phone calls to the crew to help people do good work and stay on schedule. This can take away from your creative time. You may have to fill shoes you are not prepared to fill in order to move the project forward. You have to be OK with making the wrong decisions sometimes and living with it for the sake of moving forward.

Show Me the Money

Raising funds for a film is a challenging task. I have worked with producers, like my brother Billie Mintz, who are excellent at finding money. Whether he is grasping for grants or finding philanthropists, Billie is excellent at motivating donors to support projects he believes in.

Unfortunately, I do not possess this skill. I can bore people to death with why I made certain artistic decisions on the film; however, donors do not necessarily want to hear this. They want to know why they should get behind it financially. If you are going to approach people to fund your film you need to be a very charismatic person that has 100% conviction that your film will succeed.

Grants are an excellent way to keep your film going. This takes time. Usually I need to stop production for a week or so to organize images, write descriptions and collect CVs etc. to submit to each grant. Grants can come from all over, like regional arts councils and network grants to help finish films. You can go to your local nonprofit partnerships or research them online. They are out there.

You may also need to submit a budget for your film. This could be a spreadsheet with “line items” of all of the tasks in your film and how much you think they are going to cost. The more specific you can get the better. Try and be realistic so that you know what it would take if it was fully funded.

To help you do this, you can go through each scene of your storyboard and plan how many elements are needed and create an assets list (backgrounds, characters, props, effects, etc.). It is a great practice as it allows you to simplify the production down to nuts and bolts.

It is in this scheduling that you will also find places to create shortcuts and cut costs (i.e. reuse backgrounds and possibly animation). Taking the time to really think through each scene economically will allow you to plan each step of your film in an organized way.

Working with Minimal or No Budget

One of the most difficult things for me about working on independent films is not having a budget to hire people. However, even if you have little or no money you can get work done. Since it is rare that I am paying regular rates, it is difficult to demand that any task to be finished in a certain time; yet that is sometimes the exact thing that draws other artists to working on a short film. It is the ability to work on something with a creative outlet without a demanding schedule. This frees people up creatively to develop work for their portfolio.

When you hand off work to others you have to understand that this is a team effort. This means that sometimes you have to hand over some of your creative vision. Although you are the director, know that other artists can, and should be able to, bring their creativity to your project. In fact, this is often the reason that artists want to work on low or no budget projects. If the crew feels that you trust their creative decisions they are apt to produce their best work. So be open to interpretation of your idea.

When you are working on a project for a long time it is important to find ways to keep it moving. Even if this means that on some days you produce only one drawing or send a few emails. A project like this is like a large steam engine; all of the pieces working together make it move at a steady pace, even if it’s moving slowly. But once stopped, it is much more difficult to start it up again.

In Conclusion

With all of my preproduction complete, I now launch into production with renewed energy. At the same time, I am very aware that there will be obstacles ahead.

Due to my career, I am not able to work on this film full time. I depend on my winter and summer breaks.

Using the first steps, as outlined in this chapter, to develop and nail down my story with a clear premise and development art to support it, I have a structure that I can rely on. With my stop-and-start schedule, I can feel confident that I am creating animation that is hinged on a working story and will lead me to a film that I am happy with.

For anyone out there thinking of starting an animated short, making a film takes bravery. To set out on this path, you will need both sides of your brain (artistic and productive) to solve complicated problems. It will take a calm demeanor and a positive attitude to work with and, sometimes, coach others. Always try to keep yourself and crew motivated during every long, arduous step of the way. Sometimes the end of the film can seem so far away that it feels like it will take you years to complete. You have to find ways to challenge yourself and the team to keep going. Whether you finish one small prop design, or complete the animation for a scene, it is important to celebrate small successes.

Ultimately you have to believe that your film will one day get done. Believe it in your heart and know that each drawing, each email, is taking you one step closer to finishing.

Filmmaking to me is a process. Through time, I have learned to try and sit back and enjoy the ride. Far too many people have labored over this film; therefore, it would be a shame if time were not taken to show my appreciation. I have worked with some excellent designers, artists, animators, story artists, sound designers, musicians, actors and art directors in the industry and in the university and I would like to thank them all for their contributions and support.

All hail animated filmmaking.

Stay tooned!

Image from Countin’ on Sheep, Animation Drawing, Aubry Mintz, Clean Up Dori Littell-Herrick, Color Jennifer But. Copyright Aubry Mintz, all rights reserved.

Additional Resources: www.ideasfortheanimatedshort.com

- Case Studies:

- See more about Countin’ on Sheep including animatics and production clips.

- The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore, including a “making of” film, film clips and notes from Brandon Oldenburg and Adam Volker.

- A Good Deed, Indeed including animatics, staging notes, and production notes.

- Designing for a Skill Set. Notes, examples and interviews with shorts producers on traditional animation, stop motion animation, computer animation, modeling, lighting and collaborative projects.

Pitching Stories: Sande Scoredos, Sony Pictures Imageworks

Sande Scoredos was the executive director of training and artist development at Sony Pictures Imageworks. She was committed to working with academia, serving on school advisory boards, guiding curriculum, participating on industry panels, and lecturing at school programs. She was instrumental in founding the Imageworks Professional Academic Excellence (IPAX) program in 2004. Sande chaired the SIGGRAPH 2001 Computer Animation Festival and was the curator chair for the SIGGRAPH 2008 Computer Animation Festival.

Sande produced Early Bloomer, a short film that was theatrically released. Her other credits include: Stuart Little, Hollow Man, Spider-Man, Stuart Little 2, I Spy, Spider-Man 2, Full Spectrum Warrior, The Polar Express, Open Season, Spider-Man 3, Surf’s Up, Beowulf, I Am Legend, and Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs.

Before the Pitch: Register Your Work

Before you pitch your idea to anyone, your family, friends, your uncle Joe that works at a studio, or even random strangers, protect everyone—and your idea—by finding out who owns the rights to your idea. Do not talk about your idea until you have gone through the registration process or have an agent. You never know who is listening at Starbucks. If you are pitching for a school project you may find that your school already owns the rights. Likewise, if you work in the entertainment industry, your company may own the rights to anything resembling intellectual property. Ask your career services advisor or legal department about ownership rights and be sure to read your deal memo and contract agreement.

Most studios will only take pitch meetings through an agent. That is to protect you and them against copyright claims. For information on copyright filings, check the United States Copyright Office website, http://www.copyright.gov/. Read the guidelines carefully and follow the procedures.

Know Who Will Hear Your Pitch

Now, prepare for that pitch.

Successful pitches are carefully designed and orchestrated. Many brilliant ideas have fallen by the wayside due to poor pitching skills.

Whether you are pitching a 30-second short to your animation professor or an epic to a studio executive, find out who is going to hear your pitch.

You have just a few seconds to grab their attention and convince everyone in the room that your story is worth telling. How you describe it, visualize it, sell it, and sell yourself will all work for you or against you.

First, be honest and decide if you are the best person to make the pitch. If you get flustered speaking to a group, then let someone else do the talking. Not everyone needs to be part of the formal presentation so play to your strengths.

Talk to the “gatekeeper,” the key contact who is setting up the meeting, and ask him or her to tell you who might attend. If you can, find out their titles and what influence they have on the process. Then do your homework.

The World Wide Web is a wealth of information. Check out the backgrounds of each person who may be in the meeting.

- Try to get a recent picture of each person.

- What types of projects do they like?

- What projects have they worked on?

- Where did they grow up?

- What college did they attend?

- What projects are in their catalog? Do they already have an animated film about two talking zebras? Oops, your project is about two zebras so think about how your project fits into their plans.

- Get your facts straight and then double check them. Just because it is on the web or IMDB does not make it true.

Why is this important? If you can find a relevant personal connection, then you can tap into that with a casual chat, discover mutual acquaintances or interests. But be careful. You want to stand out just a little more from the other pitches and be remembered in a good way. Your pitch should always be short and to the point, not too deep or detailed or it can get boring. You want a balance of well-rehearsed but not memorized, engaging and delivered with enthusiasm but not clownish, and delivered with confidence and passion for the project.

This business is all about relationships so you want to connect with the people in the room.

Preparing for the Pitch

Make sure you know your story. Research your idea and know what else is out there that remotely resembles it—is there a character, city, situation, movie or game that is similar to yours? You can bet that someone at the pitch will say this sounds like XYZ, the classic film from 1932 directed by some obscure foreign director. Assume that anyone in the pitch session has seen it and heard it all. Nothing is worse than the silence you hear that follows the comment, “What else have you got?” A potentially embarrassing moment can turn in your favor if you can intelligently discuss the other work, and its relationship to yours. You will look good if you not only know of this piece but can intelligently discuss this reference.

You also want to make sure you have the rights to the properties and characters. Say your story centers around a landmark building in downtown New York. Believe it or not, you may not be able to obtain or afford the rights to use that building. Same goes for characters and music. If your story cannot be made without that specific Beatles song, consider the reality and cost of acquiring the rights.

If your project requires getting the rights, be prepared to discuss the status of your negotiations in the meeting. If you do not have an original concept and cannot afford to obtain rights for existing properties, check out the properties in the public domain.

Read the industry trade publications to see what types of projects are going into production. If there is something similar to your proposal, then you should be able to address any concerns about copyright infringement upfront and explain what makes your idea better. Let the people hearing the pitch initiate talk about what actors or other talent would be good for the project.

You can show you are looking at the whole package by suggesting the entertainment value, genre, audience age and appeal of your project. Describe the concept giving a general sense of the visuals for the characters, environments and style. Use sketches, color drawings, color palettes, reference material, special lighting, video clips—anything that will get the visuals across. Sometimes you can get into the room early to stage the pitch. This is another benefit to knowing the “gatekeeper.” Remember, you are pitching to people who hear dozens of ideas and you want them to remember your project. If you can entertain them, they will see you can entertain audiences too.

Be ready to answer questions about finances and marketability since there may be financial people at the pitch.

At the Pitch

Remember that your pitch starts the minute you arrive—in the parking lot or in the elevator—you never know who you might run into so be nice to everyone. Once in the room, have a friendly handshake, thank them all for meeting with you and tell them you admire their work. Show them by your posture, body language and demeanor that you are enthusiastic and excited. Don’t be overly intense. Get everyone’s name in the room and try to identify the leader, but don’t forget to make eye contact with each of them.

You need to conquer the whole room. Dress appropriately and watch your language. Listen to all the ideas and suggestions with openness and encourage suggestions. Show them how you work with others.

After the Pitch

Have a closing prepared. Never end your pitch with “Well, that’s it.” or “So, what do you think?” End with a positive note and thank them again emphasizing how much you want to work with them. Ask them if they have any suggestions and show your willingness to make adjustments.

It helps to have some sort of “leave behind” object, something more creative than a business card or demo reel. For a story about dogs, maybe a small stuffed animal with a creative dog tag containing your contact information and the name of the project.

Within a week, follow up with the “gatekeeper” and see if you can get a pulse on interest in your project.

Hand-written thank you notes are welcome but emails are usually not. Keep track of everyone you pitch to with a journal tracking names, dates, titles, and contact information. Selling your idea is really about relationships and at the end of the pitch, you want everyone in the room wanting to work with you and confident your project is their next winner.