Chapter 8. Motivators

The team was now performing as an agile team with high bandwidth communication, self-organization, collaboration, and teamwork. To ensure everyone maintained the highest level of motivation, Lydia wanted to find out more information regarding what motivated each member of the team. This way she and the team could best ensure each individual on the project remained satisfied.

This chapter discusses three factors that influence the motivation of team members:

• Individual workplace motivators

• Leveraging personal strengths

Individual Workplace Motivators

DISC explains how people will behave. Workplace motivators explain why they behave as they do. As mentioned in Chapter 2, “Behaviors and Individuals,” if you master understanding DISC you can often tell a person’s behavioral profile just by observing their body language combined with the way the person communicates. Motivators are different. You cannot tell what motivates a person just by observation. They are therefore often referred to as “hidden motivators.”

Similar to how DISC indicates that everyone has a blend of four behaviors, workplace motivators indicates that everyone has a blend of six motivators. But the dominant motivators drive why they do things.

Some of the DISC providers also offer motivator assessments. The following paragraphs describe the six motivators that comprise the blend.

Theoretical

Individuals who rank high for the theoretical motivator have a need for learning. They have a passion for knowledge and discovery of truth. They love ideas, explore new interests, and have a desire to learn about almost anything. They seek to observe and reason.

Utilitarian/Economic

Some providers of motivation assessments call this category the economic motivator, and others call it utilitarian. Regardless of the category name, people who have a high score in this category have a need for practicality, utility, and financial gain. They tend to feel more secure when they have and accumulate tangible wealth. They often have a drive to feel financially secure in later years. They want what is useful, practical, and efficient.

Aesthetic

Those who score high in the aesthetic category have a tendency to appreciate beauty, nature, the environment, pleasant surroundings, unity, and balance. They continually search for beauty and harmony in everything they do. They are typically highly aware of their inner feelings and their surroundings. They value the environments where they work and live and have a desire to experience new things, activities, and places.

Social

Socially motivated individuals have a need to help others. They may even have a passion to help others and feel fulfilled when they succeed. They are less concerned about profit than for the needs of others. They tend to sacrifice their own needs for the needs of others and to help others.

Individualistic/Political

Some providers of motivation assessments call this category individualistic, and others call it political. Individuals strong in this category tend to have a need for personal power, influence, and fame. They have a desire and a passion to be at the top of an organization. Title is important. They have a passion to control others: people, money, assets, and so on. They like having responsibility, individually and within the team.

Traditional/Regulatory

Depending on the provider, this category is called either traditional or regulatory. People who rank high in this category tend to have an interest in rules, unity, order, and tradition. They believe in structure; there is a right and a wrong way to do things. They have a passion to search for the highest meaning of life and look for rules to guide their behaviors. They typically live by a set of standards or a belief system and encourage others to also embrace these rules/beliefs. They like to have rules and regulations and to do things “by the book.”

Why Is This Important?

In DISC, there are no good or bad behavioral profiles; people are just different. The same goes for motivators. There are no right or wrong motivators. It is simply that people are wired differently, and what motivates one person may not motivate another.

Individuals perform best when they are in roles and environments that leverage what motivates them. For example, if people are highly motivated by learning (the theoretical motivator) and are on a project or team where there is no opportunity to learn, they will not be satisfied, will most likely experience some stress because of this, and may eventually quit.

Knowing each member of the team’s motivators can help team members perform tasks or do things that match their needs whenever possible. As examples, have a theoretically motivated individual lead efforts on analyzing a new technology required for the project; allow the aesthetically motivated person to sit in the cube by the window; have the politically motivated person integrate the newly acquired organization into the team. Because agile teams are self-organizing, it is valuable for team members to know one another’s workplace motivators in order to be cognizant of each other’s needs.

Work can change from “work” to “fun” when the job closely matches and satisfies a person’s motivations or needs.

Strategies for Motivating

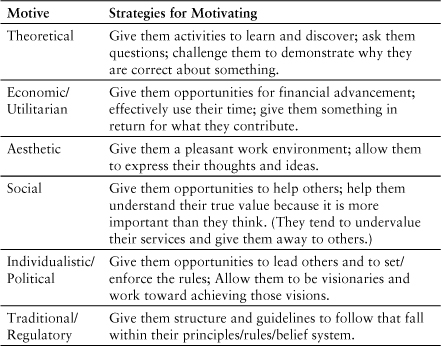

Table 8.1 provides examples of strategies for motivating others depending on their motivational profiles.

Table 8.1 Strategies for Motivating

As a real-world example, there was a senior vice president (SVP) in a company in the financial services domain that was under stress because he had promised a critical system would be complete by a certain date but was behind schedule. He therefore told the team to work nights and weekends to ensure the project was completed on time. He gave an incentive to the project manager by telling him that he would be promoted to a vice president (VP) if the project were implemented on time. Similarly, he attempted to motivate the developers by offering a financial bonus if the date were achieved. Now, aside from violating many agile principals by not maintaining a sustainable pace; by promising an arbitrary project end date to stakeholders; and by telling the team what to do in a command-and-control like manner, there were additional flaws in the SVP’s actions. It turned out that the PM was not actually motivated by a VP title because his individualistic/political component was one of his least important motivators. Moreover, the majority of the development team was motivated mostly by the theoretical motive, and most had a low economic motivator.

At first the motivation of an increase of money was appealing to some of the team members. But as the project dragged on longer and longer, and as many nights and weekends were required, the project began to unravel further and was unsuccessful at the end. Even if the members were motivated by these incentives, it still would likely have failed in this particular case. But one interesting observation from this experience was that most individuals tend to assume that the motivations of others match their own. The SVP, who was highly motivated by title and money, assumed everyone else must be. He did not realize that people are wired differently.

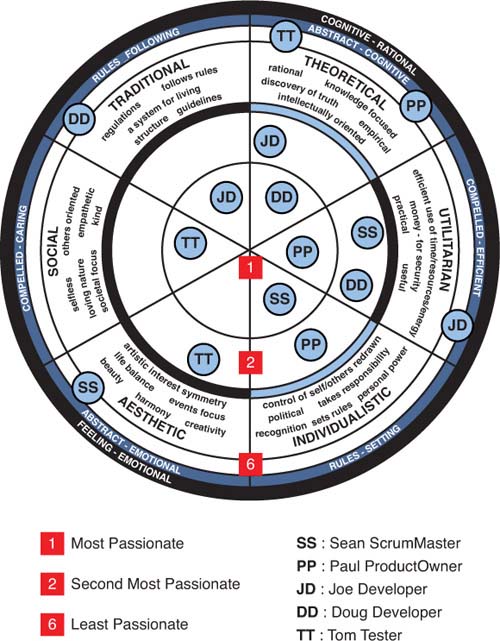

Somewhat similar to the concept of a DISC wheel discussed in Chapter 6, “Behavior and Teams,” some workplace motivator providers supply a “wheel” of workplace motivators for a team. Figure 8.1 shows an example of a wheel, provided by The Abelson Group. The team members’ top motivators are shown in the center circle, their second highest motivators in the second circle, and least passionate motivators in the outer circle.

Figure 8.1 Team Motivators Wheel—The Abelson Values/Motives/Work-Related-Passions Wheel™ is an adaptation of the Target Training International, LTD. Motives Wheel and is a trademark of The Abelson Group™.

The wheel provides a simple visual representation to quickly view the workplace motivators of every team member and to also observe similarities within the team.

Leveraging Strengths

The second element that greatly affects motivation of each member of the team is the ability to leverage natural strengths in day-to-day activities. The book, Now Discover Your Strengths, by Marcus Buckingham discusses how individuals who leverage their strengths will be most successful and happiest in their jobs.

Chapter 6 discussed DISC and how team members may become overly stressed when acting in a role that conflicts with their natural behavioral styles. Similarly, team members can become stressed when performing daily responsibilities that do not align with their natural strengths. As a real-world example, a colleague was asked to play a role in a desk job writing architectural design documentation when his core strength was communicating with people. His greatest strength and most successful roles performed in the past were those of a coach, mentor, instructor, and change agent. When playing the role of an architect however, he was exhausted at the end of each day and eventually became burnt out on the job. Needless to say, he was quite unhappy while playing this role.

Understanding your team members’ strengths and having everyone perform tasks that best use these strengths can result in the highest performing teams and the most motivated team members.

Leadership and Environment

Even if individuals work in jobs that align with both their workplace motivators and strengths, it is also critical to work in a good environment that fosters respect and autonomy in order to remain highly motivated. An applicable quote comes from Patrick M. Lencioni’s book, The Five Dysfunctions of a Team, where he says, “Not finance. Not strategy. Not technology. It is teamwork that remains the ultimate competitive advantage, both because it is so powerful and so rare.” It is amazing to see companies spend millions of dollars on technologies and tools to enable a competitive advantage. Yet treating people with respect and fostering an environment of teamwork and empowerment costs nothing and is probably the most powerful thing any company or team can do to enable success.

Command-and-control management is the antithesis of agile. Therefore, this is not an issue on agile projects. Right? Unfortunately, the majority of agile projects report into some hierarchy somewhere in the chain of command within the company. A common problem is when an agile project reports to a command-and -control manager.

The following is a true story. Two sprints into an agile project, the director called the ScrumMaster into his office and asked, “Can you explain why this agile project is so successful when we have tried agile in the past and it has never really worked?” In response, the ScrumMaster discussed many of the differences in the mechanics being employed currently versus what the company had done in the past. The discussion ranged from the task board where everyone could visually see the current project status, to the way they ran their daily standup meetings, to the demonstrations held every sprint. By the end of the project, however, the ScrumMaster realized the real answer to the director’s question.

The entire management team of this organization was deeply entrenched in a command-and-control culture. It was a common occurrence that the managers would demand and expect everyone to work the weekend and to work after 5 p.m. each day. (One manager was even known to “walk the halls” each day at 5 p.m. to see if everyone was still there.) Also the managers would rarely explain any rationale to the team regarding decisions. These managers would not be part of the solution but would just tell people what to do and often made what appeared to be unreasonable requests.

Not only did some of this behavior violate the agile principal of “a sustainable pace,” but also some of the things this management team would say and the way it treated individuals was bordering on abuse. Many employees would refer to the managers as bullies, and several said they were in fear of losing their jobs. Although this extreme behavior is not common, it is common to have some elements of traditional command-and-control behavior within a company. And this behavior is one of the most common factors leading to the detriment of agile adoption or success on individual agile projects.

Closing

DISC explains how people will behave, and workplace motivators explains why they behave as they do. Everyone has a blend of six workplace motivators, but the dominant motivators drive why they do things. Individuals perform best when they are in roles and environments that leverage what motivates them.

The book Now Discover Your Strengths by Marcus Buckingham contains a code where readers can take an online assessment to discover their top strengths. Understanding and leveraging these strengths can result in the highest performing teams and motivated team members.

Agile is about good leadership. A good leader trusts and empowers his team. For individuals to maintain a high degree of motivation, it is important that they also have a relatively high degree of autonomy. Command-and-control managers will hopefully read this chapter, reflect on their own behaviors, and subsequently change.