8 Formal and informal unpaid employment

Introduction

A widespread assumption has been that when one engages in formal labour, it is paid. However, it takes but a moment’s reflection to realise that some formal employment is not paid. To see this, one has only to think about unpaid internships in the private, public and third sectors of the economy, which many people now undertake in order to gain work experience and improve their employability. It is also the case that potential employees of an organisation sometimes undertake one-week or one-month trials on an unpaid basis so that employers can judge their suitability for the post. In these instances, the unpaid worker usually expects an offer of paid formal employment at the end of the unpaid trial period. There is often an overlap, therefore, between paid formal employment and this so far little discussed realm of unpaid formal employment.

Although such unpaid formal employment occurs in the private and public sectors and appears to be a burgeoning realm, it is not perhaps the most significant segment of unpaid formal employment in post-Soviet societies. It is in third sector organisations (TSOs) that this practice is perhaps most prevalent, where it is more commonly termed ‘formal volunteering’, which refers to ‘giving help through groups, clubs or organisations to benefit other people or the environment’ (Low et al. 2008: 11). Volunteering is composed of two major types of engagement: formal volunteering, which is a form of unpaid formal labour; and informal volunteering, which involves the provision of one-to-one help on an unpaid basis to others who do not live in one’s household but in the wider community. This latter type of work practice was considered in Chapter 7. Here, we focus upon formal volunteering as a form of unpaid formal employment that sits further along the formal/informal continuum towards informality than unpaid formal employment in private and public sector organisations, but nevertheless sits firmly in this category of unpaid formal employment.

Second, this chapter addresses a work practice that has seldom been analysed in post-Soviet societies, namely informal unpaid employment. This is where somebody is employed by an organisation on an unpaid basis, as above, but the employer or employee does not adhere to all the rules and regulations required. This applies to those working on an unpaid basis in private, public and TSOs. To understand what is covered by this work practice, let us take the example of somebody engaged in unpaid volunteering by giving help through groups, clubs or organisations to benefit other people or the environment. Unlike formal volunteering, where the person adheres to all the regulations attached to such an endeavour, such as having the licences to do so, ‘informal’ unpaid employment/volunteering does not. Sometimes, for example, those engaged in unpaid volunteering in community-based groups might do so illegitimately or informally. This is what we here mean by unpaid informal employment. For example, it might occur when a community-based group is set up to care for children, but without the required licences to act as child carer. Alternatively, it might take place when operating a sporting group, community fund-raising or music event without the necessary licences. Until now, this labour practice has been little discussed in any literature.

To evaluate the extent and nature of unpaid formal labour in post-Soviet societies, we will first review previous research on both unpaid formal employment in the private and public sectors and formal volunteering in post-Soviet societies. Second, we will turn our attentions to unravelling the extent and character of this labour practice in Ukraine, along with a slightly richer and more textured understanding of its role and meanings, followed in the third section by a similar review of its magnitude and character in Moscow. Following this, and to assess the extent and nature of the more ‘informal’ forms of unpaid employment in the private and public sectors and how formal volunteering can sometimes be conducted informally, we will first interrogate the interviews conducted in Ukraine to evaluate the extent to which this is a livelihood practice and its nature, and following this, we will evaluate the Moscow interviews to again evaluate its extent and character in this post-Soviet context. The outcome will be a review of some economic practices that have so far received little attention in the literature on post-Soviet societies.

Formal unpaid employment

Formal unpaid employment, to repeat, can take the form of either unpaid internships or trial periods in the private and public sectors, or it can occur in TSOs where it is more commonly referred to as ‘formal volunteering’. In this section, we first review what is known about the extent of such a labour practice in post-Soviet societies and then, having shown the limited empirical evidence so far available, provide an analysis of the extent and nature of this labour practice from our fieldwork in both Ukraine and the Russian city of Moscow. This will provide not only an assessment of the magnitude of such a practice in post-Soviet societies, but also a richer and more textured evaluation of its character and the attitudes of people towards this form of work than has perhaps so far been the case.

Formal unpaid employment in the private and public sector

In the private and public sectors, as stated, formal unpaid labour can take the form of unpaid internships or one-week or more trials, and people often do this expecting paid employment at the end. Although this is an increasingly widely used practice in post-Soviet societies and beyond, little if any empirical evidence is available so far on either the extent to which this labour practice is being employed in post-Soviet societies or the characteristics of such endeavours. Neither, so far as is known, are there any studies on the ways in which employers use this form of labour in their overall recruitment strategies or the attitudes of potential employees to engaging in such unpaid internships and trial periods. Indeed, the only related research so far available in post-Soviet societies is on how businesses sometimes fail to pay their formal employees for protracted periods (Shevchenko 2009), which in itself is a form of unpaid formal employment. As discussed in Chapter 5, many formal businesses often do not pay their formal employees either their formal wage or the additional undeclared ‘envelope’ wage that is so prevalent in the post-Soviet labour market, meaning that formal employees often end up working on an unpaid basis for their formal employees. Below, therefore, we will report some of the first evidence available on the extent to which formal unpaid employment is used in the private and public sectors in post-Soviet societies, as well as the character of this labour practice in such societies by reporting evidence from both Ukraine and the Russian city of Moscow. Unlike formal unpaid employment in the private and public sectors, however, much greater evidence exists on the extent and character of such a labour practice in the third sector in post-Soviet societies.

Formal volunteering in post-Soviet societies

To understand the contemporary use of formal volunteering in post-Soviet societies, it is important to understand how its current configuration has been influenced by the Soviet legacy. During the Soviet period, social, economic and political activity was closely controlled by the state (Howard 2002). This allowed the Communist regime to suppress formal autonomous organisations and the development of mass-movements other than the Communist Party (Evans 2006). Close control of all social organisations provided an effective way of creating ‘good Communist citizens’ outside the official political party framework (Evans 2006). This is not to say that informal associations did not exist, but unlike western civil society arrangements, the realm of ‘voluntary’ associations representing civil society was not separate from the state. Such arrangements left a legacy of paternalistic state–society relations. Effectively, this meant that Soviet civil society was institutionalised within the state (Rose 1995). Participation was a patriotic duty for Soviet citizens (Evans 2006), not a voluntary and freely chosen activity. This hindered the development of a culture of voluntary participation (Smolar 1996). Consequently, as a space for action, civil society was not perceived as an arena which would aggregate, represent, and articulate interest and facilitate collective action between the individual and the state, but was instead seen as organised and an aspect of social control.

Despite the controlled and institutionalised nature of civil society arrangements, small and ‘illegal’ grass-roots networks did exist (Fish 1991). These independent grass-roots movements and organisations formed around intelligentsia groups, which consisted of ‘opposition-minded intellectuals [in] tight-knit, highly insular, and mutually suspicious circles’ (Mendelson and Gerber 2007: 57). Furthermore, most ordinary Soviet citizens relied on personal networks and close ‘contact groups’ (Kharkhodin 1998: 958) in order to offset any arising shortage and uncertainty present throughout the Communist regime (Rose 1995). These networks helped Soviets to mitigate the effect of the continuous scarcity of basic consumer goods, and facilitated access to other necessary resources (Ledeneva 1998). This culture favoured ‘circles of intimacy and trust among family members and close friends’ (Evans 2006: 47) and helped Russians to become proficient at circumventing the authorities and the state. Along with the institutionalised and forced nature of official civil society, it also resulted in the constriction of the space available to civil society (Crotty 2006). For Rose (1995) and Mishler and Rose (1997), these arrangements represent an hourglass society, which by definition consisted of two halves. The top-half was characterised by a rich political and social life among ruling elites (Rose 1995). Networks of cooperation existed in an informal manner, allowing individuals to secure their own (mainly political) goals. The bottom-half was also characterised by a rich social life (Rose 1995). These networks were based around the nuclear family and friends. Rose (1995) observed that this specific network organisation and hourglass nature of society led to the ‘insulation’ of the top from the bottom. As a result, there was limited interaction between the elites and ordinary citizens during the Soviet period (Rose 1995). Official civil society was managed and controlled by the state; other civic activity was informal and focused on economic rather than political objectives.

In the 1990s, continuing the process of liberalisation and faced with economic and fiscal hardship, the state apparatus withdrew from various activities and social responsibilities. This process has been labelled ‘over-withdrawal’ (Sil and Chen 2004: 363) and had a detrimental impact on ordinary citizens. As a result of this ‘over-withdrawal’, citizens had to continue to rely on their personalised informal networks because the withdrawal took place without the emergence of institutions or organisations able to take on these roles and responsibilities (Poznanski 2001). Consequently, large parts of the population in countries such as Russia, including the disabled, veterans and politically repressed, were effectively ‘forgotten’ by the state (Henderson 2008). Despite this, many still expected the state to provide for many of these abandoned basic services (Crotty 2003). However, as a result of the economic difficulties (Hanson 2003; Lavgine 2000), the state all but ceased its support for former Soviet-era TSOs. TSOs, which enjoyed virtual monopolies in providing care and services, were now unable to do so (Sundstrom and Henry 2006). A gap for independent TSOs to take on these tasks had therefore opened up.

In an environment of over-withdrawal and democratisation, civil society had the opportunity to expand its constricted space by taking on and replacing activities formerly undertaken by the state. However, many of Kharkhordin’s (1998) collectives or other informal networks exploited the subsequent political weakness of the state. With the desire to survive as forms of association, such networks engaged in activities that led to criminal extortion or self-enrichment rather than engaging in activities conducive to the building of an autonomous civil society sphere (Yurchak 2002; Volkov 2002). TSOs which did not engage in such anti-modern behaviour (Rose 1996) formed around networks outside political elites and they attempted to engage in civil activities, but faced a number of problems due to cultural and social legacies inherited from the Soviet past. Another aspect which constrained TSOs in engaging the public was the fact that the majority of post-Soviet TSOs typically sprung out of tight-knit pre-existing family and friendship networks (Cook and Vinogradova 2006), which were hostile towards outsiders. Human rights organisations predominantly reflect this development trajectory of TSOs (Mendelson and Gerber 2007). These networks did not actively pursue activities and strategies to engage the public as they were originally conceived to protect the members from the state. However, the inability and/or unwillingness to connect and engage the public aggravated the societal detachment of TSOs. This hindered TSOs in pluralising the democratic arena and impeded the institutionalisation of civil society as a space between the individual and the state. As a result, civil society remained a constricted space and further accentuated the hourglass society (Crotty 2006).

Post-Soviet civil society has not inhabited the middle ground between the state and society and is still dominated by ‘informal’ networks existing at either end of the hourglass rather than an autonomous middle ground. In addition to these inherent developmental difficulties for the third sector, the state has not shown any interest in facilitating a civil society based on collective action, interest aggregation and promoting democratisation. Hence, structures and institutions which enable such civil society arrangements to develop and operate; for example a functioning and independent judiciary, a system of social contracting or formalised vehicles for state–civil society interaction (Henderson 2008), have been notable by their absence. In combination with the above-mentioned persistent lack of generalisable trust, this constrained civil society development as a space in which autonomous intermediary agents were able to act. The lack of trust in institutions and the legacy of the specifics of Soviet forms of civil society have meant that levels of formal volunteering in post-Soviet Russia and Ukraine remain low. According to the Charities Aid Foundation’s World Giving Index 2011, both Russia (130th) and Ukraine (105th) maintain low positions in comparison with other countries (World Giving Survey 2011). Similar figures are confirmed by the European Values Survey of 1999, with Ukraine and Russia holding the third and second lowest levels of formal volunteering among European countries. These results are confirmed again by the results of the European Values Survey in 2008, in which Ukraine and Russia are positioned second bottom and bottom according to participation rates in formal volunteering. The results indicate lower levels in general for post-socialist societies compared with western European societies.

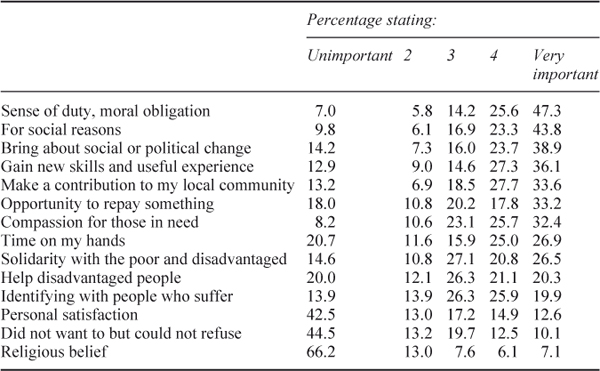

Why, therefore, do people engage in unpaid formal volunteering in post-Soviet societies? An analysis of Table 8.1 reveals that in the Russian Federation, the reasons people participate in unpaid formal volunteering is more to do with meeting their own social, emotional and personal development needs rather than the material needs of others. They engage in such endeavours for personal reasons, such as a sense of moral obligation, social reasons, bringing about the social changes they want and personal development reasons such as gaining new skills and experiences. The needs of those they are serving tend to be lower down the list of reasons given, such as helping disadvantaged people, solidarity with the poor and disadvantaged and compassion with those in need. Given this, the strong intimation is that relying on formal volunteering as a means of meeting the material needs of others is unlikely to be effective in such post-Soviet societies, since this is not the reason that most people become involved in such endeavours. It is more about meeting their own social, emotional and personal development needs, not the material needs of those they are helping.

Table 8.1 Reasons for engaging in voluntary work in the Russian Federation

Source: World Values Survey (2008).

In some instances, however, and as will be revealed later in this chapter, such formal volunteering can become ‘off-the-radar’ unpaid labour, where help is provided through groups to benefit other people or the environment but the required formalities required by law are not all fulfilled. For the moment, nevertheless, this is left aside. Instead, attention here turns to a more qualitative analysis of the role and meaning of such unpaid formal labour in people’s livelihood practices. To do this, we first report evidence from the 600 face-to-face interviews conducted in Ukraine, and following this, the 313 interviews conducted in Moscow.

Formal unpaid labour in Ukraine

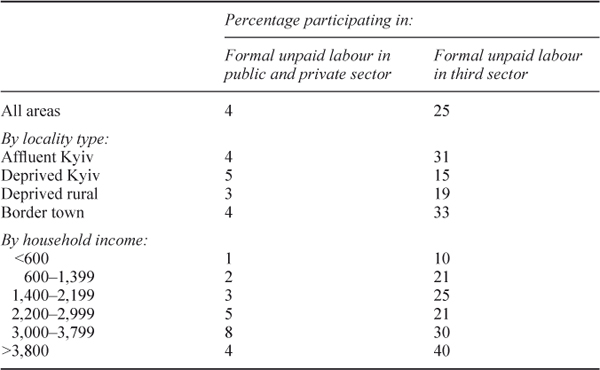

Participating in unpaid formal labour in Ukraine is not a minority practice. As Table 8.2 displays, some 4 per cent of participants had engaged in formal unpaid labour in the private or public sector in the 12 months prior to interview and a further 25 per cent had engaged in formal unpaid labour in the third sector in the last 12 months, or what is termed formal volunteering. This, therefore, is a common form of labour practice among Ukrainian households. However, it is more common as a labour practice among some population groups than others. Although formal unpaid labour in the private and public sector is fairly evenly distributed among all locality types, formal unpaid labour in the third sector (henceforth referred to as ‘formal volunteering’) is unevenly distributed spatially, with those living in the affluent locality surveyed in Kyiv being more likely to engage in such endeavours than those living in the deprived locality types studied. This reinforces previous studies in other countries, which display a statistically significant relationship between formal volunteering and the level of affluence of an area (Williams 2005a).

Source: Ukraine survey.

This is further reinforced when the relationship between participation in formal unpaid labour and household income is analysed. Not only is there a strong relationship between participation in unpaid formal labour in the private and public sectors and household income, with more affluent households engaging in higher levels of such endeavours, but so too is a similar pattern identified between participation in formal volunteering and household income. This is not perhaps surprising. Not only are more affluent households likely to be more able to invest time and resources in engaging in unpaid internships, for example, so as to increase their employability, but so too are they more likely to participate in formal volunteering in order to build their social capital and provide help to others.

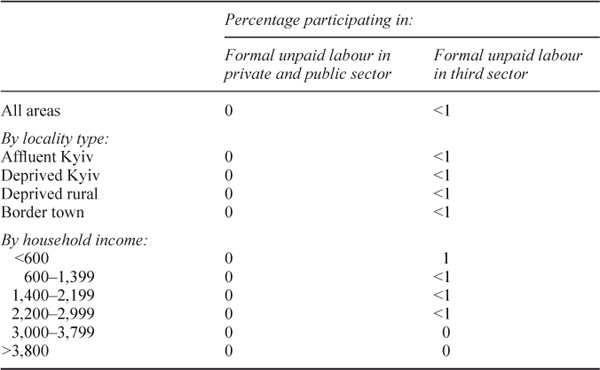

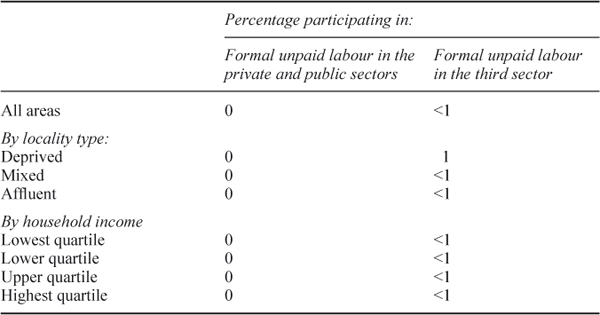

Turning to whether households use unpaid formal labour to get everyday domestic services undertaken, this Ukrainian survey reveals that in the realm of domestic services provision, this is not a widely used practice for getting such tasks completed. As Table 8.3 reveals, no households used formal unpaid labour to get these everyday domestic tasks completed, and less than 1 per cent used formal volunteering to undertake these tasks. Indeed, where formal volunteering was used, it was mostly confined to fulfilling caring functions such as for children, elderly kin and pets.

Source: Ukraine survey.

This, therefore, provides evidence to support the hypothesis discussed above that in post-Soviet states, and reflecting the Soviet legacy, most people become involved in such endeavours to meet their own social, emotional and personal development needs. Very little formal volunteering is about meeting the material needs of some client group that they are helping. This provides a clear signal that in Ukraine civil society does not represent a resource that might be drawn upon to meet the needs of marginalised groups. Is this also the case, therefore, in the Russian city of Moscow?

Formal unpaid labour in Moscow

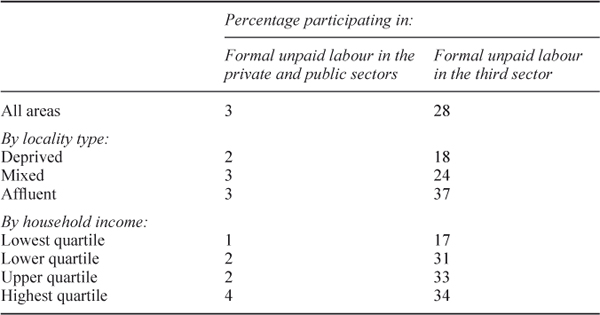

As Table 8.4 reveals, participating in unpaid formal labour in Moscow is not a minority practice. Some 3 per cent of participants had engaged in formal unpaid labour in the private or public sector in the 12 months prior to interview, and a further 28 per cent in formal volunteering. However, participation is again unevenly distributed across the Muscovite population. Although formal unpaid labour in the private and public sector is fairly evenly distributed among all locality types, formal volunteering is again not. Those living in the affluent locality are more likely to engage in formal volunteering than those living in the deprived or mixed area, similar to Ukraine.

Source: Moscow survey.

This is further reinforced when the relationship between participation in formal unpaid labour and household income is analysed. Not only are higher-income households more likely to participate in unpaid formal labour in the private and public sectors, but so too are they more likely to participate in formal volunteering. Akin to Ukraine, therefore, such households are more likely to be able to invest time and resources in engaging in unpaid internships, for example, so as to increase their employability, but so too are they more likely to participate in formal volunteering in order to build their social capital, seek emotional and social support themselves and provide help to others. Turning to whether households use unpaid formal labour to get everyday domestic services undertaken, meanwhile, this Moscow survey reveals that it is not widely used. As Table 8.5 displays, no households used formal unpaid labour in the private and public sectors to get these everyday domestic tasks completed, and less than 1 per cent used formal volunteering to do so. Indeed, where formal volunteering was used, and akin to Ukraine, it was mostly confined to fulfilling caring functions such as for children, elderly kin and pets.

Source: Moscow survey.

Given this review of the extent to which these two forms of unpaid formal labour are used in Ukraine and Moscow, attention now turns to unravelling the role and meaning of such work to those engaged in it.

Lived experiences of formal unpaid employment in the private and public sectors in Ukraine and Moscow

In Ukraine, often people work unpaid for a trial period when offered a formal job in the private or public sectors. Indeed, 30 per cent of respondents starting a new formal job in the private sector over the year prior to interview had been asked to do so, especially younger people. In Moscow, the figure was 15 per cent of respondents. A significant minority had not been offered employment at the end of their trial period. The respondents often asserted this to be a deliberate employer strategy to get ‘free labour’. For example, a person working as a courier had been told after a two-week trial that the business did not after all have any positions available and that he was not wanted, yet job advertisements for the same job appeared in the newspaper the next day. Similar stories were recounted with regard to retail stores and kiosks continuously employing people on an unpaid trial basis and saying that they were not wanted at the end of their free trial. Another example came from the financial sector, where Lesya, a graduate in finance, had been given a trial period working at one of the leading banks in Kyiv:

I was offered the job and told that there was a compulsory one-month trial period and after that, the wages being offered looked good. I worked hard and did well throughout the month but at the end of it, I was told that things had changed and there were now no vacancies. I felt disappointed obviously. Several of my friends have also had this experience.

In Moscow, Artem recounts a similar experience:

I graduated from a good Moscow university with a degree in economics. I searched hard for a good job but it was difficult. Eventually, I found a position at an insurance firm. I applied and was offered a job on condition of undertaking a six-week unpaid trial period. I was assured that this was simply company policy and that all would be OK. Anyway, at the end of this trial period, I was released from the firm, with the manager telling me that the firm had some financial difficulties etc. I understood what had happened straightaway.

Whether this is a valid depiction of an employer practice or simply a result of potential employees being inappropriate for the job is a question that needs to be asked. Although in some cases this is of course due to the individual being inappropriate for the role, meaning they are asked to leave and not taken on to a paid formal job after the trial period, this is not always the case. The evidence suggests that, given the widespread nature of this employment practice, it is in large part a tactic pursued by employers to access unpaid labour and is often an ongoing practice employed by them. As a graduate from a good university in Ukraine explains:

I left university with a degree in accounting and economics. I found a job in a bank. … I had to work for three months on a trial basis, without pay, and then my wage would start at quite a good level. I decided to give it a go and was ‘lucky’ enough to get the job. However, almost at the end of the three month trial period, my boss one day simply told me that I was not good enough at my job and there was no future at the bank for me. … At no time before was my performance discussed. I thought about complaining to someone, but to whom and what would be the point? It’s always the same in our country, the rich and powerful act as they please, enrich themselves and don’t care about normal people.

In the public sector, meanwhile, this practice of unpaid trial periods was less commonly used. Although there were instances identified of individuals undertaking unpaid internships, such as over the summer months when they are students in order to gain work experience and develop their employability skills, there were few instances identified among the respondents of any tactic among public sector employers of deliberately releasing them. Instead, this practice of using unpaid internships appeared to be much more in the unpaid employee’s interest than that of the employer when undertaken in the public sector. Indeed, gaining access to such unpaid internships was highly competitive and those who gained access to them often had to engage in ‘blat’ in order to gain access to such internships, or else pay straight ‘bribes’ to the government officials involved in order to get such a placement. In Ukraine, two examples, one from Kyiv and one from the border town, confirm such practices:

Before you graduate from university, you need to gain some practical experience. Jobs now are very competitive and thus you need some experience before applying. It is even difficult to get an unpaid internship. For me, I used a friend of my father’s to get me an internship in a state ministry. I worked hard for two months.

After finishing my studies, I wanted to work in local administration in my home city. The jobs are difficult to come by and you need some help from a contact to get ‘through the door’. I worked for three months on a summer internship unpaid after my father used a contact to get me the place. At the end of the internship, I was taken on for a probationary one-year period.

In Moscow, Larisa, a medical graduate, explained a similar situation:

Before completing my studies at the medical university, I searched for some work experience at some of Moscow’s hospitals. I soon found out that in order to get a placement, money needed to be given to the right person at the hospital. It was crazy; I ended up paying for the privilege of working for three months unpaid! I got my work experience though and have now begun my final year of studies.

Indeed, these are not the only examples of unpaid formal labour in post-Soviet states. Some 20 per cent of the private sector employees surveyed asserted that their weekly or monthly wage had not been paid to them over the past year. On the whole, this was the undeclared (envelope) wage component that had not been paid. Many Ukrainian respondents stated how, since the onset of the global financial crisis which hit Ukraine’s economy harder than most, such a situation has become more common and thus, the receipt of declared and undeclared (envelope) wages very unpredictable. An interviewee who holds a white-collar office job in Kyiv outlines such a situation below:

Our wages are very unstable now. Previously, we received an official wage and then a ‘top-up’ wage in an envelope every month. Over the previous two years, we don’t really know what we will receive each month. Sometimes, we receive our full wages, as agreed with the boss including the envelope wage. Sometimes though this isn’t the case.

Moreover, 8 per cent asserted that even the declared wage had not been paid in full. This, therefore, is a significant minority of all formal employees who were in effect working not as paid formal employees for their employer, but were also engaging in unpaid formal labour since a portion of their salary owed to them was not being paid. Such a situation is confirmed by an International Labour Office report on the effect of the financial crisis in Ukraine after 2008. The report notes how after significant decreases in wage arrears in Ukraine from 2000–2007, the arrears grew by 2.5 times during 2008–2009, being particularly problematic in the public administration, construction and healthcare segments of the economy (Kulikov and Blyzniuk 2010). Irina, a healthcare worker in the rural town outside of Kyiv, illustrates the prevalence of declared wages not fully paid:

We receive a miserly wage from the state and even that often is not paid in full. It’s been particularly bad over the past year or so, with sometimes 20 per cent of our wage unpaid. What can you do though? We continue to go to work and hope that in time, we’ll receive our wage arrears.

In Moscow, the figures in comparison with Ukraine were lower. Fifteen per cent of the private sector employees surveyed asserted that their weekly or monthly wage had not been paid to them at some point in the past year prior to the survey. On the whole, this was the undeclared (envelope) wage component that had not been paid, although 4 per cent asserted that the official declared wage had not.

Lived experiences of formal unpaid labour in the third sector

In Ukraine, one-fifth of all respondents had engaged in formal volunteering in the 12 months prior to the survey, with participation rates greater among affluent populations, as displayed in Table 8.2. In Moscow, some 28 per cent of all respondents had engaged in formal volunteering in the 12 months prior to the survey, with participation rates greater among affluent populations, as displayed in Table 8.3. Such formal volunteering, however, does not on the whole deliver material support to others. As Table 8.3 displays, less than 1 per cent of the common domestic services surveyed were provided in this way in Ukraine, and as Table 8.5 displays, less than 1 per cent of the common domestic services surveyed were provided in this way in Moscow. Instead, in Ukraine 90 per cent of cases and in Moscow 85 per cent of cases when people engaged in formal volunteering, the primary reason respondents engaged was to seek social or emotional support for themselves rather than to help others. Common responses were ‘it is a good opportunity to mix’ and ‘it provides a way of discussing things with others who are sympathetic’. This suggests that developing participation in community-based groups in Ukraine and Moscow will not meet material needs unmet by the formal market economy. It is a way of meeting the social and emotional needs of those who engage in such formal volunteering, rather than a vehicle for delivering help to others. In Ukraine, just 10 per cent (15 per cent in Moscow) participated for the primary purpose of providing material aid to others.

Informal unpaid employment

Unpaid employment is not always conducted on a wholly formal basis. Often, people are employed by a private, public or third sector organisation on an unpaid basis, but the employer or employee does not adhere to all of the rules and regulations required for this to be legitimate activity, such as the necessary licences. To start to unpack this form of work which, so far as is known, has been seldom, if ever, discussed in a post-Soviet context, we first outline the extent of this practice in Ukraine and Moscow, and following this, begin to unpack its character from the interviews conducted. This will reveal that despite receiving little, if any, discussion in the literature on coping tactics, such a practice is a small but nevertheless regular practice pursued in post-Soviet societies.

Extent of informal unpaid employment in Ukraine and Moscow

On analysing the level of participation in informal unpaid employment in Ukraine, the finding is that 1 per cent of households had participated in this labour practice in the 12 months prior to the survey. This type of labour practice, however, is unevenly spatially distributed. Participation in such a labour practice is more common in the deprived rural population (where 2 per cent had engaged in such an endeavour) compared with the deprived urban locality of Kyiv and border town (where 1 per cent had done so) or the affluent Kyiv suburb where nobody had done so. This finding that such a labour practice is more common among relatively deprived populations is further reinforced when the use of such a labour practice is analysed according to gross household income. Although none of the poorest households had engaged in such a practice, and neither had any of the most affluent households, this endeavour was very much clustered among the middle-income households. This labour practice, however, was little used to undertake everyday domestic services. Well under 1 per cent of the 44 household services were conducted by people working on an unpaid informal basis. Indeed, the only instance where it was used was associated with home repair and maintenance services where some of the labour provided by businesses in the home repair and improvement sector was provided on an unpaid informal basis.

Examining the level of participation in unpaid informal employment in Moscow, and akin to Ukraine, just 1 per cent of households participated in this labour practice in the 12 months prior to the survey. This type of labour practice, nevertheless, is unevenly distributed and, akin to Ukraine, is again concentrated in deprived populations where 2 per cent had participated in this form of work, compared with 1 per cent in the mixed area and nobody in the affluent area. This concentration of such work in lower-income populations is further reinforced when analysing the distribution of such work according to household income. In Moscow, and similar to Ukraine, it is the lower-to-middle income households that have the highest participation rates. In the lowest income quartile, 2 per cent of households participate, compared with 3 per cent in the lower-middle income quartile of households, 1 per cent in the upper-middle income quartile of households and nobody in the highest income quartile of households.

Character of informal unpaid employment in Ukraine and Moscow

Informal unpaid employment in post-Soviet societies such as Ukraine and Russia takes three forms, depending on the sector in which it takes place. First, there is informal unpaid employment in the third sector. This is where somebody engages in unpaid voluntary and/or community activity either in community-based groups or unpaid voluntary and/or community activity on a one-to-one basis, but does not adhere to all of the legal responsibilities attached to this activity such as the labour laws. As will be shown, it tends to arise because many people consider that current statutory and legal responsibilities and regulations only apply, such as when caring for others’ children, if the activity is paid. If the activity is unpaid, there is a widespread perception that regulations and legal responsibilities are somehow not applicable. The outcome is that many engaged in unpaid voluntary and/or community activity, either in community-based groups or a one-to-one basis, in effect operate on an informal basis because they are not aware of their statutory and legal responsibilities to which they need to adhere, such as when caring for children. An example of this was the unpaid voluntary work undertaken by an interviewee, Svetlana in Kyiv:

I’ve worked in the local dance centre for a few years now. It was set up to encourage local children to do some Ukrainian traditional dancing after school. I’ve always enjoyed dancing and enjoy working with children too. I don’t get paid and we don’t register anything really. There are a few of us and we simply help out in the centre when we can, in terms of organising the classes, keeping in contact with parents.

Similarly, in the rural town Volodymyr outlined his role in a local sports club for teenage boys:

I’ve worked at the local sports club for a couple of years. My son goes there and enjoys it so I decided to help out when and where I could. I don’t do much, just normally driving the boys in my van to different places if they have a match. I’m not registered at the club; it’s just a group of people who are interested in helping the club develop.

Turning to Moscow, Yuliya, a mother of two and housewife, lives in a large housing complex on the edge of Moscow. As well as looking after her two young children, she often undertakes unpaid voluntary work on the estate in a small community club:

The club was set up a while ago now and offers a place for children to go to and be supervised, often after nursery clubs finish. More and more parents now are working longer hours and struggle to pick up their children from the nursery on time. I try and help out there a couple of times a month with a friend of mine who works there also. I don’t get paid but it’s nice to help out and I stay in contact with lots of other parents in our area.

Second, informal unpaid employment occurs in the private sector. For example, in many family businesses, individual family members may help out on an unpaid basis from time-to-time, such as when there are peaks in demand. It is often the case in Ukraine that such workers are not registered, have not undertaken any necessary health and safety training and do not adhere to a multiplicity of other regulatory requirements when working in the business. Such informal unpaid employment also occurs when people are employed on unpaid internships, for example, as discussed above, but do not adhere to all the regulatory requirements regarding their employment. Again, this is often because employers are sometimes not aware that the same regulatory conditions apply to those who work in their business on an unpaid basis as to those who are employed on a paid basis. Just because somebody is not paid when dealing with a customer, for example, does not mean that the organisation is not subject to the same legal liabilities regarding customer safety.

For example, a builder operating on a self-employed basis in the border town used their teenage child as an unpaid labourer on jobs, with the child helping by things such as carrying the tools and equipment, building materials and sweeping up and tidying afterwards. Similarly, in Kyiv a small business owner, Natalya, uses her son to undertake deliveries in her flower business:

I set up the business three years ago and it is going steadily. The business involves ordering flowers over the Internet. When we have deliveries, often I ask one of my sons to help out. He is a taxi-driver and thus has the means to do this. He takes the flowers and drives to our clients all over Kyiv. He isn’t registered in our business as he is registered as a taxi driver.

In Moscow, Gennady explained how he also used his vehicle as a means to help out a friend who owns a small café:

I have a large jeep and about once a month I go to a depot and pick up a lot of goods for a friend who owns a small café in our neighbourhood. I don’t get paid for this and I don’t even ask for the petrol money. I just offered to help a while ago and the situation hasn’t changed. I’m not registered as working for the café or anything like that; it’s just the way we do things.

Similarly, Pavel explains how his friend also often helps him out in his small business:

I own a small printing firm. As we all know, the Internet has become more and more important in business. When I have some difficulties with the Internet and the firm’s website, my friend comes and tries to sort the problem out. We’ve known each other for years since we were at university together. There is no payment involved.

Third, there is informal unpaid employment in the public sector. As discussed above, it is often the case that people engage in unpaid internships in order to gain work experience and improve their employability. However, it is similarly the case that the regulatory conditions attached to their employment are similar to the regulatory conditions attached to the employment of those who receive a salary. Leonid, an engineer at a large public sector organisation in Kyiv, explains how such a form of labour manifests itself:

My son is studying at university at present, like me to become an engineer. On several occasions, he’s come and worked with my team and I on a project. This is unpaid work but it gives him experience of the real world. It’s not enough now to simply have a degree, you need a degree and experience in order to gain a good job.

In a different setting in the public sector, Irina, a schoolteacher in the rural town outside of Kyiv, explains how such informal unpaid employment works:

We are a very small school and we get little money from the education authority. Sometimes, if we have a small problem, we ask friends or acquaintances to come into the school and help. The two most common situations are problems with the lighting and with the computers. We have a couple of guys who come to the school and sort these issues out. One of them has a son at the school and is an electrician and another is a husband of one of the teachers. It works like that; we try and get by as well as we can.

In Moscow, Ludmilla, again a schoolteacher, outlines the character of such informal unpaid employment:

Regularly we have school trips for our children. We take them often into Moscow and go to the theatre or something like that. We often need volunteers to help us organise the visit. We have three or four local people who often come and help. We’ve known them for a long time and their children used to study at our school. They often come and help supervise the children when we travel into Moscow on the bus and then on the metro system.

Furthermore, in both countries parents talked about how they were obliged to provide unpaid informal labour to their children’s schools. This might be the clearing of snow, undertaking a ‘deep clean’ of classrooms before the school year starts and decorating. While this is an accepted practice, which was widely used in the Soviet period, there is a feeling that some schools receive funding for such activities and free labour is used instead and the money diverted elsewhere.

Conclusions

This chapter has reviewed the extent and nature of formal and informal unpaid labour in post-Soviet societies. Concerning formal unpaid labour, we have examined its existence and character in, first, the private and public sectors, and second, the third sector where it is often referred to as ‘formal volunteering’. The finding is that formal unpaid labour certainly exists in the private and public sectors. In these sectors, young people, in order to gain much needed work experience and often to get a ‘foot in the door’, often undertake it. In the private sector, though, there is evidence that employers potentially use this method as a deliberate way to employ ‘free’ labour so as to reduce labour costs and hence increase a firm’s profitability. Moreover, there is also evidence of formal unpaid labour occurring when employers (in both the private and public sectors) fail to pay employees’ full wages. While this problem has considerably improved since the chaotic days of the 1990s, when wage arrears were a major problem, the problem still exists and is one which has seemingly been exacerbated in the aftermath of the global financial crisis and its effect on Russia and Ukraine’s economies. Regarding unpaid labour in the third sector, this certainly exists, but importantly is rarely used to meet the material needs not met by other fields of provision, such as the formal market economy. Individuals engage in community-based associations to fulfil their own needs rather than to deliver material support to others. As such, if the intention in Ukraine and Russia is to encourage the development of civil society in order to meet material needs not met by the formal private and public sectors, or even other forms of informal delivery, then developing participation in community-based groups is inappropriate.

Second, this chapter has begun to unravel a form of work that has so far been seldom discussed in post-Soviet spaces or beyond, namely unpaid informal employment. This takes many forms depending on the sector in which it occurs. What distinguishes it from paid informal employment is that although it is unregistered and unregulated by the state, it is not paid but unpaid endeavour, and what distinguishes it from unpaid formal employment is that while unpaid formal employment adheres to workplace regulations and other statutory responsibilities, unpaid informal employment does not, in whole or in part, do so. This is often because employers do not realise that the legal responsibilities that apply to paid employment are also applicable to unpaid employment, such as indemnity insurance or health and safety legislation. In sum, this chapter has revealed the diverse array of forms of paid and unpaid informal employment and how these vary according to whether such activity is conducted in the private, public or third sectors of post-Soviet society. Hopefully, therefore, this chapter will start to encourage others to begin to further unravel the different manifestations of this work practice in post-Soviet societies. If it does so, then this chapter will have achieved its objective.