9 The internal economies of the household

Introduction

It has been often assumed that self-provisioning is a leftover from a previous mode of accumulation and that the small vestiges that remain will eventually disappear as the formal market economy becomes ever more dominant (e.g. Smuts 1971). Over the last decade or so, however, there has been an emergent recognition that self-provisioning is not some minor practice in post-Soviet societies and beyond, but is extensively used by the vast majority of households in their everyday livelihood practices (Bennholdt-Thomson 2001; Bittmann et al. 1999; Gershuny 2000; Marcelli et al. 2010; Williams 2003, 2005b, 2007, 2008; Williams and Nadin 2010; Williams and Round 2008, 2010). To explain this, a range of competing explanations have emerged which variously depict those engaged in self-provisioning either as rational economic actors, dupes, seekers of self-identity or simply as doing so out of necessity or choice. Despite this, few have evaluated either the importance and prevalence of, or rationale for, participation in self-provisioning. This chapter bridges that gap.

To commence, therefore, the first section will briefly review the various perspectives towards self-provisioning in relation to both its prevalence and the reasons for engaging in such work. To evaluate critically these contrasting perspectives, the second section will then evaluate the extent of, and reasons for, self-provisioning in Ukraine, while the third section covers Moscow. This will reveal not only how self-provisioning is extensively used in the post-Soviet world, but also through a process of induction, how one can differentiate between ‘willing’ (rational economic actors, choice, identity seeking) and ‘reluctant’ (economic and market necessity, dupes) participants in self-provisioning. Having then reviewed in the fourth section the particular role of the dacha in post-Soviet societies, the concluding section will call for wider recognition of the persistence of self-provisioning in the contemporary post-socialist world and its centrality in livelihood practices. At the outset, however, self-provisioning must be defined, or what is variously referred to as ‘subsistence production’, ‘housework’, ‘domestic work’ or ‘do-it-yourself activity’. Self-provisioning here refers to work undertaken on an unpaid basis by household members for themselves or for some other member of their household that might otherwise be undertaken in the formal economy (Reid 1934; Williams 2005a). To distinguish between self-provisioning and leisure, this definition thus uses a ‘third person’ approach. That is, if the activity could be undertaken by somebody in formal employment, then it is self-provisioning rather than leisure. As will become apparent later, this issue of whether it ‘could’ be undertaken by somebody in formal employment and why it is currently not is very important in understanding the persistence of self-provisioning.

Perspectives towards self-provisioning

To review the competing perspectives towards subsistence work, first, the contrasting views on the magnitude of such production in the contemporary economic landscape will be reviewed, followed by the competing views on the reasons for engagement in such self-provisioning.

Views on the prevalence of self-provisioning

During much of the previous century, self-provisioning was perceived as a residue or leftover from some previous era that the formal market economy was steadily replacing (Braverman 1971; Smuts 1971). It was thus caricatured as a ‘peasant’ or ‘backward’ form of production (Watts 1999). This ‘modernisation’ perspective assumed that over the long run of history there had been a shift from household production for domestic consumption to a situation in which household members work for employers in exchange for wages. Individuals were viewed as increasingly selling their labour as a commodity within the labour market rather than producing goods that satisfy their own immediate needs. This was seen to have resulted in a separation or dispossession of people from the means of production, as well as a separation of the home from production. Those who previously had made goods for their own use began ‘for the first time, to use their new factory wages to purchase factory-made items in the marketplace’ (Rifkin 2001: 81). The result in this view has been the disappearance of self-provisioning as the tentacles of the formal market economy stretch out to envelope every nook and cranny of the modern world. However, this ‘modernisation’ perspective, representing self-provisioning as disappearing in the modern world and persisting only in a few minor enclaves, is highly contestable. It depicts the economy as increasingly composed of a single mode of production (i.e. the formal market economy) and people as reliant on only one form of work (i.e. formal employment) for their livelihood.

By reconceptualising self-provisioning as one of a plurality of labour practices used by households to secure a livelihood, then a very different perspective towards such work emerges. Adopting a ‘diverse economies’ or ‘whole economy’ perspective towards self-provisioning, the argument is that the subsistence ‘economy’ (i.e. people and households relying on this as their principal mode of production) hardly exists today. Indeed, Williams (2010b) identifies that just 6 per cent of all households in Central and Eastern Europe rely primarily on self-provisioning for their livelihood. However, self-provisioning has not disappeared. Even if goods production has moved out of the household, households still engage in an extensive range of self-servicing, ranging from routine housework, cleaning windows, cooking, gardening, child-and elder-care through to car maintenance, as well as home maintenance and improvement activity. The movement of goods production into the marketplace, therefore, seems to have been only partially followed by a shift of service provision (Williams and Nadin 2010; Williams and Round 2008, 2010; Williams and Windebank 2001a). As Bennholdt-Thomsen (2001: 224) puts it:

Anyone who thinks a subsistence orientation should be banished ‘to the stone age’ or ‘to the Middle Ages’ or to the Third World, because in our developed society we have allegedly outgrown both self-provision and worries about subsistence, has failed to recognize that subsistence does not disappear, but rather changes through history and takes different forms in different contexts.

Seen through this ‘diverse economies’ lens, self-provisioning is ubiquitous. Every day, members of households cook meals, clean, tidy, mow, iron, repair and maintain goods. The interesting question, of course, is whether the extent of such work is relatively minor compared with the formal economy. Until now, there have been few evaluations of the extensiveness of self-provisioning relative to other labour practices. The only exception is time-budget studies which reveal that in many developed economies, over half of working time is spent engaged in unpaid work (Gershuny 2000; Williams 2005a). These time-budget studies, however, do not signify the importance of self-provisioning in overall livelihood practices, or explain why people use self-provisioning to undertake tasks.

Explaining self-provisioning

Two broad approaches have been adopted when explaining self-provisioning. On the one hand, wider theorisations of consumption and the consumer have been applied. On the other hand, a structure/agency debate has been played out, viewing it as conducted out of economic necessity and/or as a matter of choice. As will now be shown, both approaches suffer from intractable problems. Those applying broader theorisations of consumption and the consumer have explained self-provisioning in three contrasting ways. First, a rational utility maximisation model of consumption and the consumer has been employed, which derives from neo-classical economic thought. Here, participants in self-provisioning are believed to view their home as a business investment and to wish to maximise the market value of their property. As such, they weigh up the costs of their subsistence work against their investment return and the opportunity costs of doing this rather than spending their time on other activities (Brodersen 2003).

A second theorisation of consumption and the consumer adopted to explain self-provisioning portrays the consumer as a dupe or passive subject whose aspirations are formed and manipulated by the mass media, served and fuelled by retail businesses (Slater 1997). Here, self-provisioning is seen to have been co-opted by the market economy, such as DIY retailers, and those participating in self-provisioning are portrayed as passive subjects and dupes fooled by the latest marketing-inspired fads (Mintel 2002, 2005, 2006). A third and final theorisation of consumption and the consumer used to explain self-provisioning represents consumers as manipulating commodities to produce symbolic meanings and constitute identities (e.g. Buck-Morss 1989; Campbell 2005; Crewe 2000; McCracken 1988; Willis 1991; Wolff 1985). Seen through this lens, self-provisioning is conducted to realise effects which convey individuality and self-identity. The problem with all these theories, however, is that they focus upon why households decide to undertake particular tasks (e.g. building a summer house). They do not consider why one labour practice (e.g. self-provisioning) is used rather than another (e.g. formal employment). Building a summer house, for example, may of course be a product of: a rational economic person seeking to improve the market value of their property; a consumer responding to media-inspired aspirations, and an attempt to express individuality by acting as a manipulator of symbols. However, one does not need to use self-provisioning to build the summer house to achieve these ends. These ends could just as easily be achieved by employing a tradesperson. Such theories therefore tell us little in practice about the rationales for self-provisioning.

A second approach towards explaining self-provisioning adopts a structure/agency analytical lens, considering whether such endeavour is conducted out of economic necessity and/or as a matter of choice (Williams 2004a, 2004b, 2008). Earlier studies of various forms of self-provisioning, such as DIY, assumed it was conducted out of economic necessity because households could not afford to outsource the task to a tradesperson. However, there has been a growing recognition that some do so out of choice (Davidson and Leather 2000; Mintel 2002; Munro and Leather 2000; Williams 2004b). The intractable problem, however, is that this structure/agency dualism often does not exist in practice. As Williams (2004a) identifies in urban England, in over 80 per cent of instances where DIY was used, both economic necessity and choice were co-present in participants’ motives. At present, in sum, competing perspectives exist regarding the importance and prevalence of self-provisioning, as well as the rationales for participation in such endeavour. Few studies, however, have evaluated critically these competing perspectives. Here, therefore, we start to bridge this gap.

Evaluating self-provisioning in Ukraine

As Krantz-Kent (2009: 48) remarks, self-provisioning occurs when people ‘perform services for themselves or their households rather than purchasing those services’, and as Budlender (2010) demonstrates, such self-provisioning is prevalent in economies across the globe. Ukraine is no exception. As noted in Chapter 4, although less than 1 per cent of surveyed households relied solely on self-provisioning to ensure their livelihoods, almost 8 per cent relied on this as their main source of livelihood, with a secondary livelihood practice to support them, and 17 per cent said it was their second most importance practice. Therefore, self-provisioning, in all its forms, including, for example, the self-growing of food, plays a significant role in Ukrainian households, as over 25 per cent state it plays an important role in their lives. Its importance is demonstrated further when households were asked the form of labour that was used to last complete a range of everyday tasks ranging from household chores such as cleaning to significant repairs. As Table 9.1 shows, 71 per cent were last undertaken on a self-provisioning basis.

Table 9.1 Percentage of everyday tasks undertaken using self-provisioning in Ukraine, by task

| Task | Percentage of all tasks last conducted using self-provisioning |

Wash dishes | 93.7 |

Wash/iron clothes | 93.4 |

Cooking | 93.4 |

Shopping | 93.3 |

Book-keeping | 92.9 |

Routine housework | 92.8 |

Clean inside windows | 89.5 |

Evening childcare | 84.5 |

Daytime childcare | 79.1 |

Tutoring | 77.1 |

Wallpapering | 71.6 |

Tend sick | 71.6 |

Make/repair tools | 65.0 |

Replace broken window | 64.0 |

Indoor painting | 57.7 |

Make/repair furniture | 51.6 |

Make/repair clothes | 51.1 |

Make/repair curtains | 54.1 |

Maintain appliances | 46.4 |

Improve flooring | 39.5 |

Plumbing | 37.0 |

Improve kitchen | 33.5 |

Improve bathroom | 32.3 |

Hairdressing | 29.3 |

Double glazing | 15.4 |

ALL | 70.7 |

Source: Ukraine survey.

Clearly, not all tasks are equally likely to be conducted using self-provisioning, with the least likely being installing double-glazing (15 per cent), hairdressing (29 per cent), improving the bathroom (32 per cent), improving the kitchen (33 per cent), plumbing (37 per cent) and flooring (39 per cent). Given that the tasks more likely to be completed using self-provisioning are small tasks, it obviously seems that it is more common for larger, more complex projects to be outsourced. However, this does not mean that they necessarily then fall into the formal sphere, as only 48 per cent said that they paid someone formally. The remainder either used friends or family who have the skills and tools to complete such work, or they paid an ‘outsider’ cash in hand to undertake it. Such findings directly support the arguments in Chapter 3 that the modernisation thesis must be challenged as it assumes that self provisioning is no longer an important practice in modern societies. There is some variation, however, in the prevalence of such practices across income groups. As Table 9.2 highlights, lower income households are more likely to use self-provisioning, with the lowest income groups doing so in 76 per cent of instances compared with 38 per cent in the highest income households.

| Percentage of tasks last conducted using self-provisioning | |

All | 70.7 |

<600 | 75.8 |

600–1,399 | 79.2 |

1,400–2,199 | 72.9 |

2,200–2,999 | 59.3 |

3,000–3,799 | 62.8 |

>3,800 | 38.3 |

Source: Ukraine survey.

While this might suggest that lower-income households undertake such tasks out of necessity, this is not always the case, as will now be shown.

Motives for self-provisioning in Ukraine

Why, therefore, is self-provisioning used by households? Rather than design the survey using closed-ended questions so that responses had to fit into pre-defined categories (e.g. cost, choice), the decision was taken at the survey design stage to generate more grounded theory using an open-ended question and a follow-up probe, namely ‘what was your primary reason for doing the task in this way?’ and ‘is that the only reason?’. Having generated these qualitative responses, the next task was to group them together according to the common phrases and terms used to explain the reasons for participation in self-provisioning. Table 9.3 displays examples of the responses given, along with how they have been clustered into groups of explanations.

Table 9.3 Typology of motives for self-provisioning

| Examples of rationales | Reason for selfprovisioning | Type of selfprovisioning | |

‘I did it to save money’ | Economic necessity | ||

‘I didn’t have the money’ | |||

‘You cannot find reliable tradespeople’ | Reliability of tradesperson to turn up | Reluctant self-provisioning | |

‘Tradesman are not available to do this job’ | |||

‘Tradesman do bad workmanship’ | Reliability of tradesperson with regard to quality and trust | ||

‘I am wary of tradesmen’ | |||

‘Tradesmen do bad jobs’ | |||

‘I increased the value of my home’ | Rational economic calculation | ||

‘It was an investment in my house’ | |||

‘I enjoy doing creative things’ | Pleasure gained from self-provisioning | Reluctant self-provisioning | |

‘I got satisfaction doing it’ | |||

‘Because it was pleasurable to do’ | |||

‘To create something unique’ | Individualising endproduct/self-identity | ||

‘To personalise my home’ | |||

‘To show who we are’ | |||

‘So our home displays our identity’ |

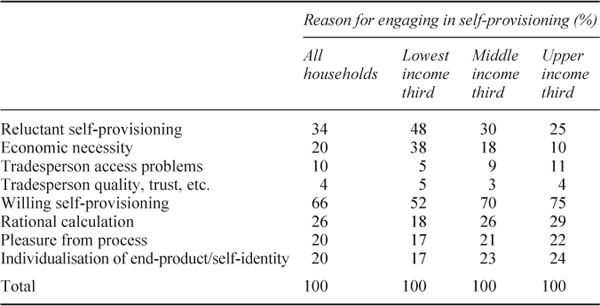

The outcome of this inductive approach is a more grounded typology of the reasons for self-provisioning that reflects how participants represent themselves as either ‘reluctant’ or ‘willing’. Those viewing themselves as ‘reluctant’ engage in such endeavours either because they cannot afford to outsource the task or due to problems with regard to finding and using tradespeople, such as getting a tradesperson to turn up, the perceived inferior quality of the end-product and trust issues related to leaving them alone in the home. For these participants, self-provisioning was often not their first choice but their chosen option. For ‘willing’ self-providers, meanwhile, self-provisioning was more often their first choice and undertaken for reasons ranging from an economic desire to maximise the value of their home (akin to the neo-classical model of the consumer), the pleasure they get from self-service activity (akin to the choice model) or the satisfaction received from creating an individualised end-product, completing a job, mastering a skill or simply doing something for oneself (supporting post-modern theories of the consumer). Table 9.4 reports the results. This reveals that people are more likely to cite ‘willing’ rather than ‘reluctant’ reasons with two-thirds of tasks conducted on a self-provisioning basis being conducted by willing participants and one-third by reluctant participants. However, this varies according to household income, with high-income households more likely to be willing while lower-income households are more likely to use self-provisioning reluctantly.

Table 9.4 Primary reason for conducting self-provisioning in Ukraine: by household income

Source: Ukraine survey.

Thus, it can be seen that only about 20 per cent of tasks within the household are undertaken out of economic necessity, although this rises to 38 per cent in lower-income households. Therefore, it cannot be stated that this is the dominant reason. However, no other competing theory as to the rationale behind such practice offers a fuller explanation. For those who argue, from a neo-classical viewpoint, that every task is undertaken as an economically rational calculation aimed at getting the best return on inputs, the above shows that only around one-quarter of tasks were completed through this prism. The ‘cultural turn’ approach, which would suggest that people would make such decisions out of a wish to enjoy the practices, can be observed in around 20 per cent of the undertakings. A similar percentage could be ascribed to a post-modernist argument whereby people want individualised outcomes. This, however, is more common in higher-income households, so care must be taken not to ascribe this more widely. The remaining 14 per cent can be seen to be around issues of trust and the inability to find someone suitable to undertake it. Thus, it is clear that there is not a dominant rationale across households for self-provisioning, but all rationales can be observed to a significant degree.

Evaluating self-provisioning in Moscow

To analyse the prevalence and importance of self-provisioning, the Muscovites surveyed were again asked for the work practice the household primarily and secondarily relied on to secure a livelihood. The finding is that one in 17 households (6 per cent) relied chiefly on self-provisioning to secure their livelihood. Moreover, when those relying on self-provisioning as their second most important livelihood practice are included, 10 per cent of households rely chiefly or secondarily on self-provisioning to secure their livelihood. The strong intimation, therefore, is that self-provisioning is not some minor residue existing in a few peripheral enclaves of the Muscovite economic landscape. One in ten households relies primarily or secondarily on such a practice to secure their livelihood in this post-socialist global city.

This perceived importance of self-provisioning is further reinforced when participation rates in different labour practices are analysed. Participation in self-provisioning is ubiquitous; all households engaged in this form of labour. This is not the same with other labour practices. Only just over one-third (37 per cent) had engaged in formal employment over the past year and 22 per cent in employment in the private sector. Compared with self-provisioning, therefore, participation in the formal labour market is confined to small pockets of the Muscovite population and is highly variable, ranging from 25 per cent in the deprived district through 40 per cent in the mixed district to 54 per cent in the affluent district. Examining participation rates, therefore, it is not self-provisioning which is a minor practice, existing in a few peripheral enclaves of the Muscovite population. It is participation in formal employment. This re-reading of the prevalence and importance of self-provisioning is further reinforced when examining the labour practices used by households to complete everyday tasks. As Table 9.5 reveals, the last time households undertook these tasks ranging from everyday household chores to home improvement work, over two-thirds (67 per cent) were undertaken on a self-provisioning basis. Formal labour, meanwhile, was last used in just 7 per cent of instances and only 26 per cent even involved monetary exchange. The implication is that self-provisioning is the major labour practice used to complete these everyday tasks. This is an important finding. The modernisation perspective assumes that self-provisioning is some minority practice. However, this survey reveals that self-provisioning remains the dominant labour practice used.

Nevertheless, there are variations in the tendency to use self-provisioning both spatially and according to household income. Self-provisioning is more heavily relied on by those living in deprived districts, as do households in the lowest and lower income quartile compared with more affluent households.

Socio-spatial variations prevail not just in the degree to which self-provisioning is used, but also in the nature of the self-provisioning undertaken. Lower-income households undertake a wider range of tasks on a self-provisioning basis and a greater proportion of all tasks, but these tend to be smaller, mundane tasks. Outsourcing, meanwhile, is primarily used to conduct urgent maintenance and repair jobs, such as mending a broken window, which often needs to be outsourced in order to be completed. Relatively affluent households, in contrast, conduct a narrower range of tasks on a self-provisioning basis, but these tend to be larger home improvement projects, such as building an extension. Indeed, higher-income households seem to externalise many of the mundane routine domestic tasks to external service providers in order to create free time to engage in more rewarding home improvement projects on a self-provisioning basis. Hence, there is a qualitative difference in not only the prevalence and importance of self-provisioning across populations, but also the nature of the self-provisioning conducted.

| Percentage last completed using self-provisioning | |

All areas | 67 |

By district: | |

Deprived | 78 |

Mixed | 67 |

Affluent | 62 |

By household income: | |

Lowest quartile | 79 |

Lower quartile | 74 |

Upper quartile | 64 |

Highest quartile | 51 |

Source: Moscow survey.

Rationales for self-provisioning in Moscow

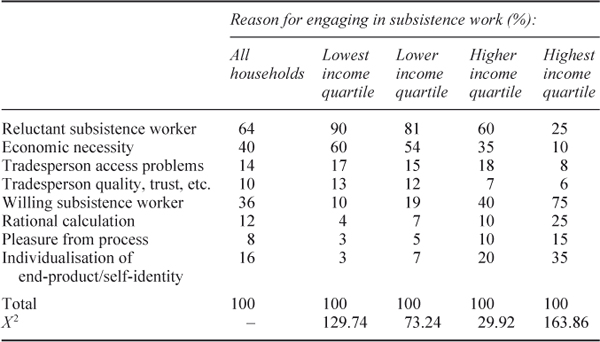

To explore why households made the choices they did, and akin to Ukraine, the survey asked, in an open-ended manner, ‘what was your primary reason for doing it in this way?’ and ‘is that the only reason?’. The responses were then classified into two broad categories, ‘reluctant’ or ‘willing’. Table 9.6 investigates the results. This reveals that the ratio of reluctant-to-willing self-provisioning across the surveyed population is 2:1; for every self-provisioning activity conducted on a willing basis, two are conducted on a reluctant basis. There are, however, statistically significant variations in the reasons for undertaking subsistence work across different household income levels. Among higher-income populations, people are statistically significantly more likely to be willing participants in self-provisioning, while lower-income populations are significantly more likely to reluctantly engage in self-provisioning.

Table 9.6 Reasons for conducting subsistence work in Moscow: by household income

Source: Moscow survey.

Note

Χ2> 16.750 in all cases, leading us to reject H0, within a 99.5 per cent confidence interval, that there are no household income variations in the reasons for engaging in subsistence work.

Unravelling the more detailed reasons for participating in self-provisioning, 40 per cent of such activity was conducted for reasons associated with economic necessity, although this rose to 60 per cent in the lowest-income households studied. Although this explanation, as might be expected, is significantly more relevant in lower-income populations, it does not explain all self-provisioning. Another reason is what can be termed ‘market failure’, namely the shortage of tradespeople, including plumbers, plasterers and so forth. Although the problem of trust has been raised when examining outsourcing (de Ruijter and Weesie 2007), the shortage of reliable tradespeople has not been before raised as an additional barrier and explanation for self-provisioning. In this survey, however, 14 per cent of self-provisioning was primarily undertaken because of the problems associated with finding a tradesperson and getting them to turn up, and a further 10 per cent due to problems with the quality of tradespersons and associated issues related to trust. Hence, one-quarter (24 per cent) of self-provisioning is a direct product of market failure.

For those portraying every aspect of personal and domestic life as operating according to market rationality, participation in self-provisioning is similarly a rational economic calculation pursued to maximise profits or save money (Brodersen 2003). However, only 12 per cent of self-provisioning was conducted for this reason. This displays that self-provisioning is not always embedded in market-like, profit-motivated, rational economic calculations. Muscovites do not view their home and labour purely as a commodity (cf. Hochschild 2003). In recent years, previous economic theorisations of consumption have been increasingly replaced by a ‘cultural turn’ that puts greater emphasis on agency. The notion that self-provisioning is conducted primarily out of choice, such as due to the pleasure gained from the process, however, is found to apply to around 8 per cent of self-provisioning, and such an explanation is more prevalent among higher income quartiles. Similarly, when evaluating the post-modern argument that self-provisioning is conducted by willing participants seeking to individualise the end-product for reasons associated with their self-identity, the finding is that one in six instances of self-provisioning (16 per cent) are motivated by such an objective, and this is especially the case among higher-income households where over one-third is conducted for this rationale. However, to assert that such a rationale is more widely applicable would be to impute a rationale popular among higher-income groups onto the wider population.

The role of the dacha in household economies

Having examined the self-provisioning that takes place within Russian and Ukrainian households, we here turn our attention to look at the role of the dacha, a plot of land outside of the urban area, in the household economy. The dacha is a plot of rural land that normally has some form of accommodation on it, ranging from the most basic ‘hut’ to the multi-million dollar homes of the newly rich. Typically, time is spent on the dacha during weekends during the spring and then for an extended period over the summer, although there is a growing tendency for richer families to build properties that can be lived in all year round. During the Soviet period, land was given to households by the state, usually via their employer. Thus, there are regions of land where mainly military personnel or workers from a certain ministry, for example, have their dachas (see Lovell 2003, for an excellent historical overview). In the Soviet period, when overseas travel was not available, for the majority the dacha was a holiday from the city and a place where food was grown to bypass shortages.

The role of the dacha during the post-Soviet period has gained much academic attention. The majority of these studies have explored the economic reasoning behind the domestic production of food and which income groups were undertaking this self-provisioning practice (see, for example, Clarke 2002; Southworth 2006; Wegren 2004). Seeth et al. (1998) and Clarke (2002) were dismissive of the importance of domestically grown food to the incomes of poorer households, while Southworth (2006) argued that as production had increased during times of economic crisis, it must have some importance. However, as Round (2006), Pallot and Moran (2000) and Pickup and White (2003) argue, reducing domestic food production to economic rationality overlooks the multitude of ways in which the outputs are utilised in everyday life.

Across the household surveys conducted in Ukraine and Moscow, 26 per cent of respondents stated that they have access to land where food is grown for their consumption and 24 per cent have land where no food is grown, where the dacha is used mainly as a site of relaxation, an ‘escape from the city’. However, the relationships of this latter group to food grown in the region reveal much about post-Soviet informal practices. When interviewing households who have land but do not grow food, many discussed how they obtain food from the surrounding area. This could be bought from street markets, exchanged with neighbours, given freely from family and friends who do grow food and/or foraged from common land. As an interviewee in Kyiv recalled:

We get our meat from the village [where their dacha is located]. Everyone has relatives in the village who can get products. You cannot trust the meat that is sold in shops so we get it from relatives who work on the farms as it is ‘home grown’ [and] therefore of good quality.

Many interviewees also picked berries from common land, which are often taken back to the city and stored for the winter. For many, though, the dacha is a site of relaxation and recuperation from the city and its stresses:

I would die without my dacha. I am too old to grow food there as the soil is of a poor quality and requires a lot of work which I now cannot do. So I spend my time just relaxing. Growing flowers and talking to my friends who also spend the summer there is how I spend my days. The air is so good here I feel healthier the moment I arrive. It allows me to regain my health and when I leave in September I feel prepared for the coming winter months.

While this is an extreme example, numerous interviewees discussed how they are so exhausted from their multiple informal practices, they do not know how they would cope without the relaxation the dacha provides. Turning to the findings of the survey in relation to the importance of domestically grown food to the household, the results in both Ukraine and Moscow contradict the assertions of those who dismiss its role as a provider of food. Among those with land, 74 per cent stated that the produce was either ‘very important’ or ‘important’ to their diet. However, only 20 per cent said that they would be unable to buy the food if they did not grow it. Consequently, the rationales must be analysed further. For the majority, the food they grow has a substitutive role in the household, by which is here meant that they could afford the good they grow but by growing it themselves they can spend the money on other items. As a construction worker says about his growing of food:

We don’t buy fruits and vegetables as we have all this in our vegetable garden. We grow things all year round and in the summer we preserve what we grow to help us through the winter. Our garden is very important in our life and family budget as we have children so there is always something we need to buy for them. If we had to spend all our money on food we would really struggle.

It is common among interviewees to grow food that is expensive to buy but which requires little effort, such as berries. Such products would be unobtainable otherwise for families living on or near the subsistence minimum. As opposed to Clarke (2002), the surveys in both Ukraine and Moscow showed that the importance of domestic production was linked to household income. Using the respondent definition of a realistic subsistence figure, it was found that 82 per cent living below this figure said that their domestic food production was important to the household, compared to 50 per cent with incomes above this level. The food-growing process is also important to them. The outputs are seen as ‘organic’ and interviewees discussed with great pride the fact that they were able to produce their own food:

What we are eating here we just picked an hour or so ago. It is fresh and it is healthy as we know there are no chemicals on it. It tastes much better and we know it is the result of our hard work.

With so much uncertainty surrounding one’s position in the formal labour market (see Chapter 5), regaining some sense of control over everyday life is of valuable importance to many of those interviewed (see also Caldwell 2011 for further discussion on the importance of the food’s organic nature). As the example at the very beginning of this book highlighted, some households sell some of the food they produce. This practice was observed more among senior citizens, having few other economic opportunities open to them. For some households, this practice is of great importance, as the following woman in Kyiv discussed:

My husband is disabled and I cannot work as I need to look after him. Our only formal income is his benefit payment, therefore the income we can get from selling what we grow on our land is of vital importance to our lives. We try and save as much as we can over the summer as it is impossible to stand on the streets to sell things when it reaches minus thirty in the winter!

Although the daily income from selling such produce is often relatively low, given that pensions are so small, it still makes an important contribution to the household budget. As an interviewee from Uzhgorod states:

I work twelve hours per day from late April to late September to earn enough to survive the winter. I start working on my land before the snow melts; something like in April. Then I dig and plant radish, dill, and onion. Usually they are the first things I sell on the market. In a good month I can earn more than my pension. I have no idea how I will live when I am not able to dig or to carry my goods to the market.

As such quotes display, the domestic growing of food by this group for sale is not an alternative economic practice, a resistance to capitalism or a return to a pre-modern era of self-provisioning, but one borne out of marginalisation and in many cases out of desperation. The process is labour intensive and although they gain pride in their ability to survive, it often comes at a cost to their health. As discussed in Chapter 6, such practices are seen by the state as an attempt to cheat it out of tax revenues. This group would argue that it is the actions of the state (i.e. low pensions, poor healthcare services and the need to pay bribes) that forces them into such endeavours. For the elderly the food grown by relatives is also of great importance. The vast majority of interviewees discussed how they received a considerable amount of their fresh food from relatives with dachas. This enables them to spend their meagre pensions on other essential products. The dacha, therefore, despite some who have espoused the contrary, reflecting the lives of rich Russians and Ukrainians, remains for many an important resource in their livelihood practices without which they would be suffering far more than is currently the case.

Conclusions

Until now, few studies have evaluated either the contrasting views on the prevalence of self-provisioning or the rival explanations for participation in such endeavours in post-Soviet societies. Analysing the pervasiveness and importance of self-provisioning, this chapter has found little support for the ‘modernisation’ perspective which portrays this endeavour as a residue or leftover from a previous era persisting in just a few minor enclaves of the modern economy. Not only is self-provisioning a ubiquitous practice which a significant minority of households in both Ukraine and Moscow rely heavily on to secure their livelihood, but the vast majority of everyday tasks in households are conducted on a self-servicing basis. The clear implication is that everyday life in Ukraine and Moscow is more a ‘do-it-yourself’ rather than a ‘do it for me’ culture. Some households, moreover, do more on a self-provisioning basis than others. Indeed, the lowest-income households conduct more on a self-provisioning basis than the highest-income households. This, however, is not because self-provisioning is purely a product of economic necessity.

Economic necessity is more common as an explanation in lower-income households, but cannot be relied on exclusively to explain all self-provisioning. A fuller and more comprehensive explanation for self-provisioning requires a move beyond this simplistic explanation. As has been here revealed, some self-provisioning is conducted on a ‘willing’ basis by those who engage in such endeavours either as a rational economic calculation, for pleasure or to seek self-identity from the end-product, while other self-provisioning is conducted on a ‘reluctant’ basis by those forced into such endeavour either for economic reasons or due to problems with finding and using tradespeople. The finding is that although reluctant self-provisioning is more likely among lower-income populations, in higher-income populations people are markedly more likely to be willing participants.

In sum, this chapter has revealed that self-provisioning in these post-Soviet economies is not some minor residue left over from a previous era as the modernisation perspective asserts. Instead, it is a persistent, important and pervasive feature of the economic landscape in the post-Soviet world. With this in mind, we now turn our attention to drawing some conclusions about the role of informal economies in the post-Soviet world.