Lorraine Eden, Li Dai, and Dan Li

Introduction

A scientific field of inquiry is a socially constructed entity, consisting of a community of scholars who share a common identity and language (Kuhn, 1962; Nag, Hambrick and Chen, 2007). The boundaries of a discipline may be more or less fuzzy, but scholars working in that field have a consensual understanding of the domain's essential meaning.The “name” or title is an important signifier of the boundaries of a particular discipline. Asking “What's in a name?” is therefore to inquire about the essential meaning of a scientific field of inquiry. In this chapter we examine three fields of inquiry that on the surface appear to have substantial overlap: international business, international management, and international strategy. Our goal is to clarify the domain statements for these three fields, building on a foundation built by earlier scholars who have explored the definition and domain of these disciplines.

One of Jean Boddewyn's important scholarly contributions has been his work in defining and clarifying the domain of international business (Boddewyn, 1997) and international management (Boddewyn, 1999; Boddewyn, Toyne and Martinez, 2004). In this chapter, we build on his foundational work to explore the meanings of three fields of inquiry: international business (IB), international management (IM), and international strategy (IS). While the three fields on the surface appear to share considerable overlap, we argue that they are conceptually distinct. As Boddewyn (1999: 4) notes, fields of inquiry must have socially defined boundaries; we must define the scope of what is “in” and what is “out,” recognizing that the definition may be subjective and transitory. Our analysis is therefore time bound: we examine all three fields as of 2010, the start of the second decade of the twenty-first century, 20 years after Boddewyn started us down this path.

Our chapter proceeds as follows. We start by exploring the meaning of the term “interna-tional,” building on Boddewyn's work in this area. We then move to developing a domain statement for each of the three fields of inquiry: IM, IB, and IS. We then conceptually link the three fields, and show the relations among them graphically. Lastly, we link each field of inquiry to a core scholarly journal focused on publishing research in that domain, and compare the journal's domain statement with the domain statements we develop in this chapter. We conclude with some suggestions for future work in this area.

What's in the name “international management”?

Boddewyn (1997, 1999) defines international activities as those that involve crossing the borders between nation-states. The term nation-state brings in both the concept of nation (country-level economic and sociocultural variables) and state (political variables such as national sovereignty). “The implication is that if the world were made up of only one nation-state, there would be no international business” (Boddewyn, 1997: 54). Boddewyn argues that crossing borders should be defined broadly as including not only tangible and intangible cross-border transfers but also the transfer of “management resources, philosophies and practices” across national borders (Boddewyn, Toyne and Martinez, 2004: 198). Boddewyn and colleagues expand beyond this definition to include “both the crossing of national borders and the internal and external environmental diversity that organizations and their managers experience when functioning outside their home state,” which for organizations implies “an interaction between two or more cultures” (p. 200). All three authors agree that the term international refers to both the crossing of nation-state borders and to the “mental transformations generated by experiences and exchanges” (p. 209).

We now need to link “international” to each of our fields of inquiry. We start with “management” rather than “business” or “strategy” in order to build on Boddewyn's work on defining the domain of international management studies. As Boddewyn (1999) notes, the term “management” had not been defined, even by the Academy of Management as of the end of the 1990s. He notes that the term originates in the Latin word “manus” for “hand,” implying that to manage is to handle people and organizations (p. 203). Managers “plan, organize, staff, direct and evaluate” and “make decisions” with the goal of adding value to an organization (p. 204). Following Kuhn (1962), Boddewyn also argues that “management is a historically and socially constructed process” (p. 205).

The scope and focus of management is also addressed by Martinez and Toyne (2000), who examine three separate approaches to defining management as a field of inquiry: Koontz (1961, 1980), the Academy of Management's organizational structure, and Hofstede (1980, 1993).While Boddewyn (1999: 9) originally preferred to restrict the study of management to firms, Martinez and Toyne (2000) and Boddewyn, Toyne and Martinez (2004: 209) adopt a very broad view of management that includes all “socially constructed activities that take place in multiple types of organizations all over the world—whether profit-seeking, not-for-profit or public.” Martinez and Toyne (2000) argue that management inquiry is becoming (and needs to become) “increasingly complex, multidimensional and even multilevel” (p. 25). They view management inquiry as having broadened to include functions that are not directly management, but supportive (e.g., consulting and education), and management practice as “permeating all of society.”2

Building on the work by Boddewyn, Toyne and Martinez, we adopt the following simple definition of management: Management is the process used by individuals (managers) to achieve an organization's goals; that process includes the following activities: planning, organizing, directing and controlling the organization.

To develop a domain statement for international management (IM) as a field of inquiry we put our definitions of “international” and “management” together. International management (IM) as a field of inquiry is the study of the process of planning, organizing, directing and controlling the organization, which individuals (managers) use to achieve an organization's goals when the organization is involved in cross-border activities or functions outside its nation-state. However, we emphasize here the business focus of international management as a field, wherein such goals, processes, and activities pursued by managers are a subset of the numerous undertakings necessary for a business enterprise to function.

Boddewyn and colleagues (2004) argue that defining IM as “management crossing borders” is too narrow as it implies “one-way crossing” from the home to a foreign country. They argue (and we agree) that IM should be broadened to include “not only the unidirectional crossing of national borders but also the two-directional learning experienced by managers outside their home environment” (p. 195). We see our definition as including such two-way mindsets and experiences.

There are several undergraduate textbooks in international management and it may be useful for comparison purposes to look at their definitions of IM. Perhaps the simplest definition is Hodgetts, Luthans and Doh (2006), who define IM as the process of applying management concepts and techniques in a multinational environment. Cullen (2002) defines IM as the formulation of strategies and the design of management systems that successfully take advantage of international opportunities and respond to international threats. IM is about how firms become and remain international in scope (Beamish, Morrison, and Rosenzweig, 1997), and how people from many cultures work together, compete against one another, or try to cope with one another's differences (Holt, 1998). The goal of IM is to achieve the firm's international objectives by effectively procuring, distributing, and using company resources, including people, capital, know-how, and physical assets, across countries (McFarlin and Sweeney, 1998). Rodrigues (2009) argues that IM is applied by managers of enterprises, who attain their goals and objectives across unique multicultural, multinational boundaries. These textbook definitions suggest that international management is affected by the home environment where the firm is based as well as the host environment where the firm conducts business. Thus, the two-way crossing recommended by Boddewyn, Toyne and Martinez (2004) does appear in our undergraduate IM textbooks.

Does the same hold true for our IM journals? Werner (2002), in a review of the 20 top management journals, identifies three categories of IM research.The first category consists of “pure” IM research, which he defines as studies that look at the management of firms in a multinational context. Pure IM research includes topics such as the internationalization process, entry mode decisions, foreign subsidiary management, expatriate management, and so on. Werner's second category contains studies that compare the management practices of different cultures and nations, known as comparative or cross-cultural management studies. His third category consists of studies that examine management in a specific nation outside of North America. Werner argues that such studies are “international” since they provide a non-American view of management, one that is different from research that has a North American bias.

While we agree with Werner (2002) that his first two categories belong in IM as a field of inquiry, we disagree strongly with his third category. Single-country studies of management practices outside of North America are domestic, not international studies. There is no cross-border, either one-way or two-way, interaction or activities involved in such papers and as such they should not be included in IM research.

The same problem arises in Kirkman and Law (2005), who define international management research in the Academy of Management Journal (AMJ) as including articles or research notes with either (1) one non-North American author or (2) data collected from outside of North America or (3) the topic is related to international or cross-cultural management issues. By our definition of international management, only the third category belongs in IM. Single-country studies, regardless of where the data were collected, if written on domestic topics, should not be included in IM, nor should domestic management papers written by non-North American authors.3 While publishing more papers written by non-North Americans and papers using non-North American databases clearly internationalizes the journal, these activities do not mean that AMJ is publishing international management research.4

What's in the name “international business”?

Toyne and Nigh (1997: 27), in their edited book on IB as a field of inquiry, express concern that, “what is lacking in the extent literature is the question ofwhat is the proper conceptual domain of the construct labeled ‘international business’.” In the book, several authors provide their own definitions of the domain. Toyne (1997), for example, presents a philosophical outlook on the field of IB, arguing that IB needs a common knowledge-generating purpose. Wilkins (1997: 35) conceptualizes IB as a sub-field of the broad field of business studies, limited to the study of the “firm that extends over borders.” Schollhammer (1997) argues in favor of a diversity of perspectives and the existence of competing theories of IB. Finally, Behrman (1997: 86) argues for IB to be re-embedded in a societal context, stating that “if IB is not a policy discipline, it is irrelevant.” The conflicting views of these authors, written almost 15 years ago, suggest that the domain statement was still very much in flux.

Boddewyn's chapter in the Toyne and Nigh book (Boddewyn, 1997) conceptualizes IB as broader than Wilkins, not limited to the firm and encompassing many levels of analysis. IB includes the economic, socio-cultural, and political dimensions of business, and emphasizes the multilevel nature of research in the field. While the sina qua non of international business is the multinational enterprise (MNE), a business that conducts value-adding activities in two or more nation-states, the MNE is not the only or perhaps even the most important form of enterprise studied in international business. Boddewyn argues that the domain of IB is not limited to the MNE or to firms, but includes macro concepts such as trade and investment as well as micro concepts such as the firm's resources, governance structure, and relationships. Boddewyn therefore defines the domain of IB as “negotiated trade and investment that join nations and cross state barriers, as performed by firms (private and public) operating and interacting at various personal, organizational, product, project, function, network, industry, global and other levels” (p. 60).

It is useful to look at undergraduate textbook definitions of international business. Daniels and Radebaugh (2001) define IB as all commercial transactions, private and governmental, between two or more countries. Griffin and Pustay (2005) similarly define IB as consisting of business transactions between parties from more than one country. Cullen and Parboteeah (2010) provide a definition in terms of the activity: IB activities are those a company engages in when it conducts any business functions beyond its domestic borders. Others define IB in terms of the entity that conducts it, as any firm that engages in international trade or investment (Hill, 2007). Czinkota, Ronkainen and Moffett (2003) provide a more detailed definition of IB as consisting of interrelated transactions that are devised and carried out across national borders to satisfy the objectives of individuals, companies, and organizations.These textbooks therefore see IB research as first of all concerned with firm-level business activity that crosses national boundaries or is conducted in a location other than the firm's home country. Second, IB is construed as dealing in some way with the interrelationships between the operations of the business firm and international or foreign environments in which the firm operates (Wright and Ricks, 1994).

In this chapter, building on the foundational work of these earlier scholars, we develop a domain statement for IB, by starting from the definition of “international” we have used above: international activities are those that involve crossing the borders between nation-states. A simple definition of a “business” is a commercial or industrial enterprise that sells goods or services to customers. The domain of business studies is therefore the study of business as an enterprise (an organizational form), its activities, and its interactions with the external environment (that is, with other actors, organizations, and institutions such as consumers and governments). Putting these two definitions together, a definition of international business must focus on the business enterprise and its activities as it crosses nation-state borders.

We therefore propose the following domain statement: International business as a field of inquiry is the study of enterprises crossing national borders, which includes cross-border activities of businesses, interactions of business with the international environment, and comparative studies of business as an organizational form in different countries. Building on Eden (2008), we argue that the study of international business has six sub-domains: (1) the multinational enterprise (MNE) (its activities, strategies, structures, and decision-making processes); (2) interactions between MNEs and other actors, organizations, institutions, and markets; (3) cross-border activities of firms; (4) the impact of the international environment on business; (5) international dimensions of organizational forms (e.g., strategic alliances) and activities (e.g., entrepreneurship, corporate governance); and (6) cross-country comparative studies of businesses, business processes, and organizational behavior in different countries and environments.

We can also look at these six sub-domains through different lenses. Toyne and Nigh (1997) and Martinez and Toyne (2000) argue that IB studies involve three different sets of lenses, which they call the extension, cross-border, and interaction paradigms. The extension paradigm asks how environmental differences across countries (e.g., variations in national institutions) affect the business enterprise. An example of a research question using the extension paradigm would be asking how differences in legal systems between the United States and Germany affect the human resource management practices of a German firm in the United States. The cross-border paradigm asks how operating simultaneously in two or more countries affects the business enterprise. An example of a research question in the cross-border paradigm would be investigating whether the introduction of a free trade agreement would cause MNEs to close down R&D centers in peripheral countries and centralize these activities in the largest member country. The interaction paradigm is the most complex; it addresses the impacts of sustained interaction between businesses from different countries. An example here would be to ask whether emerging market multinationals that engage in foreign direct investment in developed market countries are able to learn and transfer best practices back to the parent firm and other parts of the MNE network.

What's in the name “international strategy”?

Let us now turn to our third focus of inquiry, international strategy. When referring to a research field/discipline, international strategy has been frequently used as an abbreviation for international strategic management. To define international strategy (IS), we must first start with a domain statement for strategic management, which is one of the youngest of the business disciplines and therefore can be seen as an emergent field (Hitt, Boyd and Li, 2004: 3).

Because of the newness of the discipline, Nag, Hambrick and Chen (2007) used a large survey of strategic management scholars to develop an implicit consensual definition of the domain/ field of strategic management. The domain statement they develop in their paper is: “The field of strategic management deals with (a) the major intended and emergent initiatives (b) taken by general managers on behalf of owners, (c) involving utilization of resources (d) to enhance the performance (e) of firms (f) in their external environments” (p. 942).

Three additional representative definitions of strategic management as seen by management scholars are provided in Nag, Hambrick and Chen (2007: 946): strategic management is (a) “an explanation of firm performance by understanding the roles of external and internal environments, positioning and managing within these environments and relating competencies and advantages to opportunities within external environments”; (b) “the process of building capabilities that allow a firm to create value for customers, shareholders, and society while operating in competitive markets,” or (c) “the study of decisions and actions taken by top executives/TMTs for firms to be competitive in the marketplace.”

A straightforward definition from a leading undergraduate textbook by Hitt, Ireland and Hoskisson (2009) defines strategic management as “the full-set of commitments, decisions, and actions required for a firm to achieve strategic competitiveness and earn above-average returns” (p. 6) and strategy as the “integrated and coordinated set of commitments and actions designed to exploit core competencies and gain a competitive advantage” (p. 4).

Key to all of these definitions is the focus on managers developing strategies to improve the firm's competitive advantage and performance. If management is the process by which managers achieve an organization's goals, then strategic management must be seen as a subset of the management discipline, focused explicitly on formulation and implementation of the strategic aspects of management.

Tying these general definitions of strategic management together with the definition of “international” we have used above, we propose the following simple domain statement for IS: International strategic management (or international strategy) as a field of inquiry is the study of the comprehensive set of commitments, decisions and actions undertaken by firms to gain competitiveness in the international environment.

The undergraduate strategic management textbooks define international strategy as strategies designed to “enable a firm to compete effectively internationally” (Griffin and Pustay, 2005: 309). Deresky (2008) suggests that the global strategic formulation process, as part of overall corporate strategic management, parallels the process followed in domestic companies. The differences in the two processes are due to forces governing the international business environment, which include host governments, political and legal issues, the current exchange rates, competition from local business, government-supported firms, other MNEs, and cultural variation among nations. Differences on all these dimensions result in variations in the strategic planning process among MNEs. Therefore, many of the questions addressed by strategic management scholars (e.g., what/ where to produce and where/how to market) are the same for international strategy scholars, with added complexity due to the increasing geographic spread of resources, markets, management, and/or competition (Griffin and Pustay, 2005; Ricart et al., 2004;Tallman and Yip, 2001; Wild, Wild and Han, 2005).

The field of IS is relatively new and deserves much scholarly attention. One of the future IB research areas identified by Werner (2002) is international strategy (or, in his words, MNC strategy). Ricart and colleagues (2004) searched all articles published in the Journal of International Business Studies from 1970 to July 2003 and found only 84 articles with the word “strategy” in their abstracts. Their review of these “strategy” articles indicates that, while extensive knowledge about MNCs has been accumulated in the IB literature, we do not know much about international strategy formulation or “how MNCs should define their strategy in a complex and rapidly evolving globalized environment” (p. 178).

We suggest that it is helpful to understand the emerging field of international strategy by examining the six elements of the field of strategic management, as identified in Nag, Hambrick and Chen (2007), and then investigating how the addition of “international” to each element alters the domain statement. If this approach is valid, then IS can be decomposed into six elements, similar to those proposed by Nag et al. (2007).We therefore have a more fine-grained (and we believe superior) domain statement for IS: International strategy as a field of inquiry is the study of (1) the major intended and emergent initiatives, including cross-border initiatives, (2) taken by general managers on behalf of owners, (3) involving utilization of domestic and/or foreign resources (4) to enhance the performance (5) of firms (6) in the international environment.

The first element of strategic management, “major intended and emergent initiatives,” involves the understanding and formulation of business and corporate strategies. In this grouping, Nag et al. (2007) place terms such as innovation, acquisition, investment, diversification, alliances, and transaction (p. 942). When interpreted from an IS research perspective, we need to build in a cross-border element and the international environment. As an example, where mainstream strategy research may focus on industry diversification, the issue for IS scholars is more geographic diversification or the combination of geographic and product diversification by MNEs. Similarly, alliance research by strategic management scholars may focus on scope and governance, whereas alliance research in IS tackles the formation and management of alliances with partners from different countries or located in foreign countries where the institutional and cultural differences among partners add complexity to alliance effectiveness.

The second element in the Nag et al. (2007) definition of strategic management is “managers and owners,” where the authors place terms such as incentives, compensation, agency, board, and ownership. When interpreted through an IS lens, this element raises the issues of, for example, agency problems stemming from the challenges of managing parent—foreign subsidiary relationships, cross-country comparisons of boards of directors, and the new varieties of capitalism.

The third element, “utilizing resources,” is associated with terms such as capability, asset, slack, resources, and knowledge. Utilizing resources has been explored in the IS literature, for example, in terms of exploitation and exploration of resources inside and outside a firm's home country. Recently more attention has been shifted to questions such as bi-directional knowledge transfers, rather than one-way transfers from parent firms to subsidiaries, metanationals, and knowledge exploration by emerging market multinationals.

The fourth element, “enhance the performance,” highlights the sameness of the ultimate question to both the strategic management and IS fields—why do some firms perform better than others? The difference between strategic management and international strategy lies in the evaluation of an MNE's performance in the international arena rather than in a single market. The fifth element, “firms,” is typically examined without regard to nationality or location by strategic management scholars. IS scholars, on the other hand, focus on categories such as multinationals, foreign subsidiaries, born global firms, and emerging market multinationals.

The last element, “external environment,” includes terms such as competition, market, contingency, uncertainty, threats, and risk (p. 943). In IS research, the external environment clearly facilitates investigation of topics such as global market scanning, institutional differences and distance, liability of foreignness, political risk, and exchange rate exposure.

We conclude that there is much to be done in developing the field of international strategy, and that reinterpreting Nag et al. (2007) through an international lens provides a way forward in this field. Interestingly, Nag et al. (2007) completely ignore the international aspect of strategic management in their paper. The term “international” appears only once in a sentence arguing that international business has disappeared as a discipline because it has been subsumed by other business disciplines (Nag, Hambrick and Chen, 2007: 945).5 No other similar terms (e.g., global, foreign, multinational) appear in their paper, suggesting that neither the authors nor the strategic management scholars who were surveyed for the article had thought very much about the international dimensions of strategic management.

How are IB, IM, and IS related?

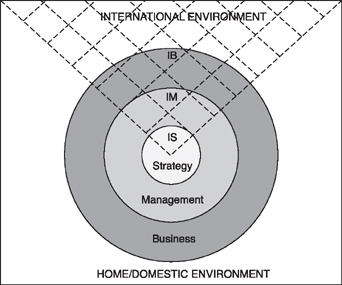

Now that we have defined the domains of international management, international business, and international strategy, how and where do these three fields of inquiry overlap? Boddewyn (1997) argued that conceptualizing a domain such as IB does not necessarily require throwing in “the whole kitchen sink” of all its determinants, processes, and outcomes. For our three domains. what is in? What is out? Figure 4.1 provides a graphical answer to these questions.

Figure 4.1 IM, IB, and IS as fields of inquiry: aVenn diagram approach

In Figure 4.1, we illustrate the environmental field in which businesses operate as a large rectangle. We conceptualize the business enterprise as an organization, pictured as a large circle in the environment. Implicit but not shown (for simplicity) in this picture are multiple other circles in this field representing other actors, organizations, institutions, and nation-states. We separate the environmental field into two parts, domestic (home) and international, showing the border lines that must be crossed when a business moves across borders from the domestic to the international environment. The dotted lines therefore represent boundaries between nation-states.

As illustrated, international business is the overlap between the cross-hatched triangle (the international environment) and the circle (the business enterprise). This overlap figuratively captures the domain of the field of inquiry international business studies, showing that IB is about business crossing national borders, which includes comparative studies of business as an organizational form in different countries, cross-border activities of businesses, and interactions of business with the international environment.

Inside the business circle is a smaller circle that represents management of the business enterprise. We show the domain of management studies as inside the domain of business studies because the field of business is much broader than that of management, and includes, for example, marketing, finance, accounting, and so on (Eden, 2008). International management is therefore the intersection of the management circle with the cross-border boundaries of the international environment. Conceptually, we see IM as the process of planning, organizing, directing, and controlling the organization, which managers use to achieve an organization's goals when the organization is involved in cross-border activities or functions outside its nation-state. IM therefore lies within the domain of IB.

Lastly, we graphically position the strategic management (strategy) circle inside the management circle because strategic management is only one of the core management processes. Management of functions such as finance, accounting, and marketing are typically not included in the study of strategic management.

International strategic management or international strategy is therefore the intersection of the strategic management circle with the cross-hatched triangle representing the international environment. International is broader in scope than international strategy. The former is preoccupied with both the primary and support activities of the firm along its international value chain; while the latter is concerned with the overall enhancement of the firm's international competitiveness. In this way we conceptualize IS as a field of inquiry focused on understanding major intended and emergent initiatives, including cross-border initiatives, taken by general managers on behalf of owners, that involve utilization of domestic and/or foreign resources to enhance the performance of firms in the international environment.

Our graph accordingly reflects our belief that the three domains are nested: IS lies within IM, which lies within IB. For each field of inquiry, the key to understanding the “international” dimension is the one-way or two-way crossing of nation-state boundaries.

As a useful exercise in Table 4.1, we provide the domain statements for three journals that most closely identify themselves with the three fields of inquiry discussed in our chapter: IB: Journal of International Business Studies (JIBS), IM: Journal of International Management (JIM), and IS: the new Global Strategy Journal (GSJ). Comparing each journal's domain statement with those developed above, we argue that JIBS has, perhaps not surprisingly, the most detailed domain statement and the one that most closely fits our approach above. JIM has the shortest and least clear statement, with little to no mention of crossing borders. We recommend that JIM should clarify its domain statement so as to better match our definition. Lastly, GSJ has a broad domain statement, which again could benefit from closer attention to building a domain statement for global strategy. Perhaps the editors of GSJ, in the introductory issue, will provide a clearer domain statement for international strategy. We recommend that they build on what we have developed in this chapter.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we have sought to build on earlier work by scholars, especially by Jean Boddewyn, outlining and clarifying the domains of international business and international management as fields of inquiry. Following Boddewyn (1997, 1999), we examined the definition of “international” in conjunction with “business,” “management,” and “strategy” in order to understand the domain of each field. We identified overlaps and differences, and compared our work to the domain statements of three journals that identify themselves as focused on each field of inquiry: JIBS (international business), JIM (international management), and GSJ (international strategy). Our study suggests that the domain statement of JIBS tracks very closely with the field of international business; however, this is not the case for JIM and GSJ, which could both benefit from rewriting their domain statements more clearly.

Both IM and IB, as fields of inquiry, have long intellectual histories; IS is the newest of the three fields and the least developed. Both IM and IB have strong eclectic orientations that have been both assets and liabilities for their development into mature areas of academic study. On the asset side, the diversity in theoretical and methodological perspectives makes IM and IB research interesting and open to new ideas. On the liability side, there has perhaps been undue fragmentation and difficulty in systematic knowledge accumulation. While IB is deductive, analytical, and axiomatic, IM is practical, empirical, and prescriptive (Buckley, 1996). If each of these intellectual fields exists due to a competitive advantage, then it must, according to Boddewyn (1999), come from superior knowledge of foreign and international environments as well as their interaction with management processes, particularly internationalization.

| Journal of International Business Studies (JIBS) | Journal of International Management (JIM) | Global Strategy Journal (GSJ) |

|

The goal of JIBS is to publish insightful and influential research on international business. JIBS is an interdisciplinary journal that welcomes submissions from scholars in business disciplines and from other disciplines if the manuscripts fall within the JIBS domain statement. Theories whose central propositions are distinctively international are encouraged, as are theories where both dependent and independent variables are international. There are six sub-domains in international business studies: • The activities, strategies, structures, and decision-making processes of multinational enterprises • Interactions between multinational enterprises and other actors, organizations, institutions, and markets • The cross-border activities of firms (e.g., intrafirm trade, finance, investment, technology transfers, offshore services) • How the international environment (e.g., cultural, economic, legal, political) affects the activities, strategies, structures, and decision-making processes of firms • The international dimensions of organizational forms (e.g., strategic alliances, M&As) and activities (e.g., entrepreneurship, knowledge-based competition, corporate governance) • Cross-country comparative studies of businesses, business processes and organizational behavior in different countries and environments. |

JIM is devoted to advancing an understanding of issues in the management of global enterprises, global management theory, and practice; and providing theoretical and managerial implications useful for the further development of research. Topics include: • Improved theory and international management research • Educational methodology in the range of international management fields • Issues in the management of global enterprises, global management theory, and practice • Risk management, organizational behavior and design, human resources, and cross-cultural management |

GSJ publishes studies of any and all aspects of the environment, organizations, institutions, systems, individuals, actions, and decisions that are a part of or impinge on the practice or study of strategy and management of businesses in the global context. Topics include: • Collaboration across national boundaries, cooperation with partners on a smaller scale within many local host settings • Strategies for global expansion, diversification, and integration to develop, protect, and exploit their resources and capabilities • Cultural, institutional, geographical, economic, technological, and development distance that determine where and how to sell products • Selecting and developing the structure of global firms: organizational architecture, management systems, resources and capabilities, global networking of subsidiaries • The pursuit of strategic objectives through cross-border M&As, international alliances, and JVs, formal and informal networking, internal development, and offshored/ outsourced value-adding activities • The effect of political agreements or strife, cultural and institutional differences, levels of technological development, and other global and regional issues as they affect strategy. |

Sources: JIBS Statement of Editorial Policy (www.jibs.net), JIM website (http://sbm.temple.edu/jim/), Defining Themes of GSJ (http://gsj.strategicmanagement.net/themes.php).

We have argued in this chapter that all three fields of inquiry are nested: IS lies within IM, which lies within IB. The unifying aspect of the three fields is that they address transactions, organizations, institutions, environments, and phenomena that are not nation bound, but are distinctively international.

Notes

1 From International Studies of Management and Organization, 40, 4 (Winter 2010–11): 54–68. Copyright © 2011 by M.E. Sharpe, Inc. Reprinted with permission of M.E. Sharpe, Inc.

2 See also Hofstede (1999) on international management in the twenty-first century.

3 Ricks (1985: 1) makes this point, quoting a passage from Nehrt, Truitt and Wright (1970) on the definition of international business: “A study of marketing channels in Turkey, whether it be done by the US, French, or Turkish professor of marketing, is still a study about domestic business in Turkey. This would not be international business any more than would the study of motivational levels of Portuguese workers or the study of personal income distribution in Japan, even though each may be of interest to international business firms.”

4 Kirkman and Law (2005) find that 14 percent of the 1911 articles and research notes published in the Academy of Management Journal between 1970 and 2004 fall in the international management category. Our best estimate is that the correct figure is 5 percent, using our definition of international management. The bulk of the remaining papers classified by Kirkman and Law as IM were so categorized because at least one of the authors was non-North American.

5 We believe that fears that IB has been absorbed by other business disciplines, as expressed by Nag, Hambrick and Chen (2007), are vastly exaggerated.

Bibliography

Beamish, P.W., Morrison, A. and Rosenzweig, P.M. 1997. International Management: Text and Cases. Burr Ridge, IL: Irwin.

Behrman, J.N. 1997. Discussion of ‘The Conceptual Domain of International Business’. In International Business: An Emerging Vision, ed. B. Toyne and D. Nigh, 82–90. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press.

Boddewyn, J.J. 1997. The Conceptual Domain of International Business: Territory, Boundaries, and Levels. In International Business: An Emerging Vision, ed. B. Toyne and D. Nigh, 50–61. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press.

Boddewyn, J.J. 1999. The Domain of International Management. Journal of International Management, 5: 3–14.

Boddewyn, J.J., Toyne, B. and Martinez, Z.L. 2004. The Meanings of ‘International Management’. Management International Review, 44: 195–212.

Buckley, P.J. 1996. The Role of Management in International Business Theory. Management International Review, 35(1.1 Special Issue): 7–54.

Cullen, J.B. 2001. Multinational Management: A Strategic Approach. Cincinnati, OH: Cengage SouthWestern.

Cullen, J.B. and Parboteeah, K.P. 2010. International Business: Strategy and the Multinational Enterprise. New York: Routledge.

Czinkota, M.R., Ronkainen, I.A. and Moffett, M.H. 2003. International Business. Mason, OH: Thomson/ South-Western.

Daniels, J.D. and Radebaugh, L.H. 2001. International Business: Environments and Operations, 9th edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Deresky, H. 2008. International Management. Managing Across Borders and Cultures Text and Cases, 6th edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Eden, L. 2008. Letter from the Editor-in-Chief. Journal of International Business Studies, 39: 1–7.

Griffin, R.W. and Pustay, M.W. 2005. International Business, 4th edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Hennart, J.F. 1997. International Business Research. In International Business: An Emerging Vision, ed. B. Toyne and D. Nigh, 644–651. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press.

Hill, C.W.L. 2007. International Business. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Hitt, M.A., Boyd, B.K. and Li, D. 2004. The State of Strategic Management Research and a Vision of the Future. In Research Methodology in Strategy and Management, Volume 1, ed. D. Ketchen and D. Bergh, 1–31. Emerald Group Publishing Ltd, Bingley, UK.

Hitt, M.A., Ireland, R.D. and Hoskisson, R.E. 2009. Strategic Management — Competitiveness and Globalization, 8th edition. Cincinnati, OH: South-Western Cengage Learning.

Hodgetts, R., Luthans, F. and Doh, J. 2006. International Management: Culture, Strategy, and Behavior. New York: McGraw Hill Irwin.

Hofstede, G. 1980. Motivation, Leadership, and Organization: Do American Theories Apply Abroad? Organizational Dynamics, 9(1): 42–63.

Hofstede, G. 1993. Cultural Constraints in Management Theories. Academy of Management Executive, 1: 81–94.

Hofstede, G. 1999. Problems Remain, but Theories Will Change: The Universal and the Specific in 21st-Century Global Management. Organizational Dynamics, 28(1): 34–44.

Holt, D.H. (1998). International Management: Text and Cases. Forth Worth, TX: The Dryden Press.

Kirkman, B. and Law, K. 2005. From the Editors: International Management Research in AMJ: Our Past, Present, and Future. Academy of Management Journal, 48(3): 377–386.

Koontz, H. 1961. The Management Theory Jungle. Academy of Management Journal, 4: 174–188.

Koontz, H. 1980. The Management Theory Jungle Revisited. Academy of Management Review, 5: 175–187.

Kuhn, T.S. 1962. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Martinez, Z.L. and Toyne, B. 2000. What Is International Management, and What Is its Domain?. Journal of International Management, 6: 11–28.

McFarlin, D.B. and Sweeney, P.D. 1998. Does Having a Say Matter Only If You Get Your Way?. Basic and Applied Psychology, 18: 289–303.

Nag, R., Hambrick, D.C. and Chen, M. 2007. What is Strategic Management, Really? Inductive Derivation of a Consensus Definition of the Field. Strategic Management Journal, 28: 935–955.

Nehrt, L., Truitt, J.F. and Wright, R. 1970. International Business Research: Past, Present and Future. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Graduate School of Business, Bureau of Business Research.

Ricart, J.E., Enright, M.J., Ghemawat, P., Hart, S.L. and Khanna, T. 2004. New Frontiers in International Strategy. Journal of International Business Studies, 35: 175–200.

Ricks, D.A. 1985. International Business Research: Past, Present, and Future. Journal of International Business Studies (Summer): 1–4.

Rodrigues, C. 2009. International Management: A Cultural Approach. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

Schollhammer, H. 1997. Discussion of ‘The Conceptual Domain of International Business’. In International Business: An Emerging Vision, ed. B. Toyne and D. Nigh, 76–82. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press.

Tallman, S. and Yip, G. 2001. Strategy and the Multinational Enterprise. In The Oxford Handbook of International Business, ed. A.M. Rugman and T.L. Brewer, 317–348. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Toyne, B. 1997. International Business Inquiry: Does it Warrant a Separate Domain? In International Business: An Emerging Vision, ed. B. Toyne and D. Nigh, 62–76. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press.

Toyne, B. and Nigh, D. 1997. Foundations of an Emerging Paradigm. In International Business: An Emerging Vision, ed. B. Toyne and D. Nigh, 3–26. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press.

Toyne, B. and Nigh, D. 1998. A More Expansive View of International Business. Journal of International Business Studies, 29(4): 863–876.

Werner, S. 2002. Recent Developments in International Management Research: A Review of 20 Top Management Journals. Journal of Management, 28: 277–305.

Wild, J.J., Wild, K.L. and Han, J.C.Y. 2005. International Business: The Challenges of Globalization. Upper Saddler River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Wilkins, M. 1997. The Conceptual Domain of International Business. In International Business: An Emerging Vision, ed. B. Toyne and D. Nigh, 31–50. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press.

Wright, R. and Ricks, D. 1994. Trends in International Business Research: Twenty-five Years Later. Journal of International Business Studies, 25(4): 687–701.