Simona Gentile-Lüdecke and Sarianna M. Lundan

Introduction

In this chapter we review the development of research-driven international business (IB), commenting upon its status and aims, and looking at the evolution of its research agenda, its main theoretical contributions, the challenges and criticisms it is facing and the emergent topics of investigation.

The disciplinary roots of IB, the demarcation of its conceptual and empirical domain, its underlying bases of theories and knowledge have been and still are the subject of an extensive debate among scholars (Shenkar, 2004; Sullivan and Daniels, 2008). While most IB scholars see it as a discipline of its own, alongside finance, accounting, organization and marketing, and more than a particular application of existing core subjects defined by the functional area of business (Eden, 2008), others see the field of IB as slicing across the grain of areas of study in business administration (Caves, 1998).

Eden et al. (Chapter 4, this volume) define international business as a ‘field of inquiry in the study of enterprise crossing national borders, which include cross-border activities of businesses, interaction of business with the international environment, and comparative studies of business as an organizational form in different countries’. We follow in this tradition, and see IB as a distinct field, with its own ontology and intellectual roots. Even so, since the embryonic stages of IB research, scholars trying to explain the nature of multinational enterprises (MNEs), their investments abroad and the power and influence they wielded, looked to theory in other disciplines. This integrative, interdisciplinary aspect (Dunning, 1989;Toyne and Nigh, 1998) is a core feature of the IB field. The phenomena that IB scholars are studying are complex, and contextually deeply embedded within a dynamic environment, and can only be understood by combining theories, concepts and methods from multiple disciplines (Cheng, Henisz, Roth and Swaminathan, 2009: 1071).

In defining the domain of IB, Dunning and Lundan (2008a) view the arena of IB as comprising a unique combination of topics and methodologies that seek to understand the forms and consequences of one of the distinguishing features of the global economy, namely the behaviour and the activities of enterprises which own, control or influence value-adding activities outside their home country. Thus, IB is concerned with firm-level business activity that crosses national boundaries, and with the interrelationships between the operations of the business firm and the different national and transnational environments in which the firm operates.

Indeed, the importance of the interrelationships between the external environment and the firm is another core characteristic of the IB field. As indicated by Shenkar (2004: 168):

IB knowledge is an integrative field combining knowledge of core IB rules of the game with regional know-how (…) The general knowledge base includes knowledge of a series of fundamental tenets such as institutions, trade agreements, regional organizations and the like (…) Regional know-how is the understanding of different national environments and their cultural, religious, political and economic variations and their correlates. What IB brings to the table is the ability to ‘translate’ such context into specific inputs of business behaviour in those environments — ability that is critical because it underlies the capability of sense making. In other words it enables the researcher to make sense of their environment as enacted by others rather than as viewed from their own perspectives.

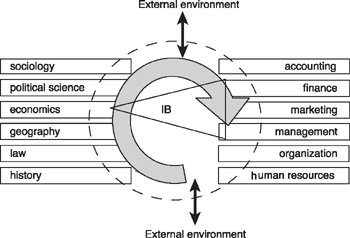

Figure 7.1 presents a cognitive map of the IB field, indicating how IB overlaps with the functional areas of business (finance, accounting, organization and marketing) and other related disciplines (economics, political science and sociology, geography, history, law and psychology) and how it influences and is itself shaped by the external environment. Following Dunning (2006: 3,4), we consider the external environment in terms of the physical environment and human environment. While the physical environment determines the ways in which human capital and physical assets are created and used to generate wealth, the human environment comprises the compilation of rules, norms and conventions and ways of doing things that define the framework of human interaction (North, 2005: 11). Reflecting the evolution of the IB field over time, the inner triangle shows the ‘breadth’ of IB research in the first two decades, while the dotted circle shows the expanding frontier in recent years. The transfer of knowledge both at the intersection of the disciplines and between them is represented by the circular arrow.

This chapter is organized as follows. The next section presents an historical review of the development of IB research from its origins to the present. Section 3 reflects on the ongoing

Figure 7.1 The cognitive map of IB research

debate on perspectives and methods to improve the rigor and relevance of IB research, while Section 4 focuses on identifying emerging research themes that are pertinent for its future development. Section 5 summarizes and concludes the chapter.

International business research from its origins to the present

The IB field as a subject of academic investigation was born in the late 1950s, and has undergone many changes and turning points in terms of its focus and trajectory, as summarized in Table 7.1. We can identify four major stages of development in this evolution.

Focus on the forces towards internationalization

In the 1950s large MNEs were not as numerous as today, and most of them were American. Many nations, including Japan and all of Europe, were more concerned with rebuilding than with overseas investment. However, the situation began to change in the following decade. By the end of the 1960s, the value of the sales of the foreign affiliates of MNEs was approaching that of world exports, and the renewal and increase of international flows of direct investment (FDI) were a key feature of the dynamism ofWestern economies (Buckley, 2002).

The focus of research in this period was on the forces and reasons that drive firms to international operations (Sharma, 1992). Industry-level studies appeared first, and these mainly

| Research agenda | Approximate dates | Topics | Country focus |

Explaining forces towards internationalization |

Post WWII to 1970s |

US FDI in Europe Managerial issues of investing abroad |

Europe US→ Europe Latin America Canada |

Explaining structure, strategy and organization of MNEs |

1970s to 1990s |

Theories of MNEs Strategies and organization of MNEs |

LDCs Japan 4 Little Dragons |

Foreign market entry Smaller firm in IB International economic integration |

|||

Explaining globalization |

Mid-1980s to 2000 |

Joint ventures Alliances Meaning of globalization Born globals |

Eastern Europe Asia China |

Explaining the impact of international environment on business; co-evolution of firms and societal institutions |

2000 to present |

How institutions and their underlying values affect mode of IB operations and MNEs' strategies; corporate social responsibility |

Emerging markets, particularly China and India |

Source: Adapted from Buckley (2002: 366).

concentrated on the oligopolistic structure of industries in which firms guard their market position and exploit their differential, monopolistic advantage (Caves, 1971; Hymer, 1976; Kindleberger, 1969). Specifically, Hymer's central proposition was that international firms entering a foreign market must possess an internally transferable ‘advantage’, the control of which gives them a quasi-monopolistic opportunity to out-compete local firms.

A turning point was presented by the Harvard Multinational Group, which presented the product life cycle model (Vernon, 1966). It did not rely on the theory of industrial organization to explain FDI, but instead delineated the process by which MNEs had moved from the USA to the rest of the world. The model was based on some basic assumptions such as that tastes and information costs vary across nations, and that products undergo change over time. However, the model proved difficult to extend to the cases of European and Japanese multinationals, whose presence was becoming more prominent (Vernon, 1974).

A different group of scholars, based in Uppsala in Sweden, sought to explain the internationalization process of firms based on behavioural organization theory (Aharoni, 1966; Johanson andWedersheim, 1975;Johanson andVahlne, 1977). They had observed that firms in Scandinavia typically took small steps in their choice of foreign locations as they gradually and sequentially internationalized. Overall, FDI was seen at this stage as driven by external circumstances, and while each of these studies explored the context of the physical environment of the world economy, little consideration was given to the human environment (Dunning, 2006).

Focus on MNEs

During the 1970s and the 1980s the field of IB changed extensively. The economic growth of Europe and Japan and the emergence of newly industrialized economies resulted in an increasing focus on international business.

Since the early 1970s, research focus had shifted towards the MNE as such, and the environment surrounding MNEs. In this period, the international, political and social climate was also becoming more conflicted regarding the effect on international business activity on the home and host countries of MNEs.

Many studies were conducted to highlight the interaction between the local environment and MNEs (Lall, 1980), and the conflict of interest between nation states and ‘footloose’ MNEs (Streeten, 1972). The concern and criticism towards MNEs was mainly expressed in terms of the impact of FDI on the physical environment, where FDI was seen as a package of resources (technology, capital, know-how) and governments found ‘the packaged form of resource transfer unacceptable’ (Sharma, 1992: 4). It was in these years that many new national and international institutions were initiated to upgrade and enforce the formal laws and regulations designed to ensure that MNEs should behave in a socially responsible manner.

The development of the theory of the MNE took a step forward by the development of internalization theory. This emphasized that MNEs arise because they are economically more effective instruments for transferring (knowledge-based) resources across borders while minimizing transaction costs in international operations (Buckley and Casson, 1976). Internalization theory predicted that a firm will grow by internalizing imperfect external markets until it is bounded by markets in which the transaction benefits of further internationalization are outweighed by the costs.

The eclectic paradigm of Dunning (1977, 1979, 1980) put forward a general framework for determining the extent and pattern of both the foreign-owned production undertaken by a country's own enterprises, and that of domestic production owned and controlled by foreign enterprises. The eclectic or OLI paradigm builds upon three interrelated components: (1) Ownership (or firm-specific) advantages, reflecting the resource base of firms, and particularly the possession of or access to intangible assets, and advantages which arise as a result of the common governance and coordination of related cross-border value-adding activities. (2) Location advantages, reflecting the main variables addressed by international economics, political science and modern institutional theory. The spatial distribution of location-bound resources, capabilities and institutions is assumed to be uneven, conferring a competitive advantage on the countries possessing them over those that do not. (3) Internalization advantages, reflecting the extent to which the enterprise perceives it to be in its best interest to add value to its ownership advantages itself rather than to sell the right to do so to independent (foreign) firms.

The rise of the global economy

In the 1980s and 1990s, growth in international trade and foreign direct investment, the emergence of the second global economy, and the fall of the Berlin Wall ‘catapulted IB into the realm of the current and the relevant’ (Eden, 2008). The more visible stance of national governments towards competing in a global market led to a focus on national and regional competitiveness, and the opening of new markets in former socialist countries led to a generation of studies on economic transition.

The 1980s saw also the emergence of alliance capitalism and of organizational heterarchies, one result of which was to ‘underscore the role of informal institutions, notably those of trust, reciprocity and forbearance, as factors influencing the success of collaborating ventures among firms’ (Dunning, 2006: 4). IB scholars focused on understanding the determinants and performance of international joint ventures and alliances, and there was interest in finding a new form of transnational organization able to cope with the new demands of balancing global scale and local adaptiveness (Bartlett and Ghoshal, 1989). The objective of the MNE came to be seen as ‘flexibility’ in order to adjust to the increasing volatility in the operating environment (Buckley and Casson, 1998).

Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, knowledge continued to be viewed as a created asset, an input, into the determinants and consequences of IB activity. However, little attention was given to the motivations, incentives and regulations which influenced the choices and strategies of MNEs.

The recent years: A shift in trajectory towards an increasing interest on the human environment

Starting in the mid-1990s, a new direction can be identified in IB research which refers to the renewed interest in various aspects of the human environment. Growing attention is now being given to the role of institutions and their underlying values in affecting the motives and patterns of activity of MNEs (Henisz, 2000, 2005). Additionally, governments are increasingly trying to influence the competitiveness of their own firms and the choice of location of inbound foreign investors by upgrading indigenous incentive structures and social capital. Indeed, institutional theory (North, 1990, 2005) has become one of the most important perspectives in international business in recent years. Researchers have applied theories from neo-institutional economics and sociology to study how the characteristics of the global, regional, national and sector-specific environments influence the strategies and performance of multinational enterprises. Studies have illustrated the importance of institutional variation for a wide range of constructs, including diversification, foreign direct investment, governance, innovation, organizational learning and social networks.

This new direction of research suggests that the physical environment is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for successful IB activity. Dunning (2006) indicates five main reasons that justify this shift in trajectory:

• the advent and impact of globalization on the physical environments and human environments;

• the widening of the economic and social objectives of both individuals and organizations;

• the increase in various kinds of endemic or intrinsic market failure, which, independently from the physical environment in which firms operate, affects the attitudes, organization and strategic behaviour of firms towards their international activity;

• the growing participation of several new economies, notably China and India, on the world economic stage, and the increasing role played by MNEs from those countries;

• the increasing informality and variations of the organizational form of IB (growth of cooperative alliances, consensual forms of inter-firm governance) due to the demands of a changing and uncertain human environment and the growing complexity of the physical environment.

All these trends reinforce the importance of content and quality of the human environment within and between firms, and of the formal institutional context shaping and defining this environment (Dunning and Lundan, 2008b). The review of the emergent topics of research, which will be illustrated in the following sections, reflects the growing focus on the human environment.

Is the IB research agenda running out of steam?

The scientific domain of IB has developed extensively from its inception as a result of the fundamental changes of the external environment where the international firm is operating. Lewin (2004:79) notes that environmental change is altering the ‘boundaries of what constitute the domain of IB’ and Eden and Lenway (2001: 387) argue that these changes represent ‘an irreversible paradigm shift in political, economic and social relations from industrial capitalism to post-industrialism’.

The increasing complexity of the IB context, which is making the task of conducting meaningful research much more challenging, has sparked a retrospective analysis on the raison d'être of the field and its research traditions (Sullivan, 1998) and has generated an intense debate on the balance between the focus and depth of IB research and the need for more ‘breadth’ in the investigation, i.e. for more interdisciplinary work.

While some scholars have suggested that IB research suffers from a ‘narrow vision’ (Daniels, 1991; Dunning, 1989; Redding, 1994; Scholhammer, 1994;Thomas, Shenkar, and Clarke, 1994; Vernon, 1994), others sustain that IB needs to become narrower in scope if it is to benefit from a unifying theory (Stopford, 1998). These authors argue that in a field characterized by a wide scope, it is difficult to reach consensus, and one is likely to make little scientific progress and permanently remain in the strait-jacket of a pre-paradigm stage (Peng, 2004: 101).

Furthermore, several reviews have expressed a sense of déjà vu in IB research. In a recent study conducted by Griffith et al. (2008) which examines the scholarly work in international business over the time period 1996–2006 in six leading international journals,1 some scholars have lamented that large parts of the work in IB are best classified as extension, if not replication of previous sources (Griffith et al.: 1230) and that the major contribution is the consideration of a new context, whether this is the country, industry or the firm.

A series of articles in the Journal of International Business Studies has also analysed the future development of IB as a scholarly discipline, reflecting on its research agenda and on its ability to produce new theoretical frameworks, able to offer relevant insights concerning the emerging themes in IB.

In one such article, Buckley (2002) argued that the IB research agenda could be ‘running out of steam’ due to the absence of a current ‘big question’ to invigorate research. Peng (2004) responded to the debate opened by Buckley (2002) by identifying specific research questions that can be addressed to drive the international business agenda forward. He sustains that ‘what determines the international success and failure of firms’ has always been the core question for IB that has served to unite most IB researchers and to demarcate the field's boundaries relative to other fields (p. 102).

However, according to Shenkar (2004), looking for the next big empirical phenomenon will serve only to paint IB as an empirically driven, atheoretical field that fails to go much beyond the descriptive, which will render it vulnerable to inevitable shifts in relevance (p. 167). He argued that there are still unanswered questions in the old paradigms, provided that IB is positioned as ‘an integrative field whose competitive advantage and added value lay in the synergetic combination of global and local knowledge that is unavailable to, and not imitable by, its major competitors, in particular economics and strategy’ (p. 161).

The same opinion is shared by Griffith et al. (2008), who argue in light of recent research (Fruin, 2007; Jones and Khanna, 2006) that we cannot easily say whether the paradigms and answers derived four decades ago continue to be relevant in the context of IB as it is today. Can the theories that have driven research in areas such as entry mode, foreign market expansion and knowledge management still help to explain these phenomena, or is there a need to review existing theories and/or create new ones?

Reflecting upon the development of IB research on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Journal of International Business Studies, Wright and Ricks (1994:700) suggested that the real challenge for IB scholars was integration: ‘While much progress has been made and much has been learned, we need now to synthesize what we are learning into broader more integrative framework. Therein lays the key challenge and the greatest potential for significant new contribution for today's international business researchers.’

Figure 7.2, adapted from Buckley and Lessard (2005), graphically shows the main issues at the core of IB research in the years since its inception, and the related theory development, looking both at international business theory and discipline-based theories. The figure illustrates that there is an increasing ‘import’ from theories of other disciplines, confirming the interdisciplinary nature of the field, while the development of international business theory moves at a slower pace. Indeed, Buckley and Lessard (2005) are worried that IB research is inadequately related to independent (i.e. discipline-specific theories), since discipline-specific theory creation that advances the state of the art was only pursued during the first flowering of the discipline in the 1970s.

Buckley and Lessard (2005) are also concerned that theories borrowed from outside the IB may now be superficially understood, badly applied and inappropriately interpreted (ibid.: 596). Hence IB researchers should avoid the trap of sheer amalgamation of theories into imperfectly integrated paradigms.

Major advances can be made if every ‘theory driven’ international business article begins with a statement of its derivation from theory and ends with its contribution to theory, however incremental. Often theoretical derivations are lost in extensive literature reviews and theoretical contributions are underweighted compared to

Figure 7.2 Issue—theory interaction in IB

contributions to practice and methodology. ‘Issues driven’ contribution should identify how/why the observation challenges/sharpens the theory, making specific reference to the relevant theory rather than just collecting interesting artefacts.

(Buckley and Lessard, 2005: 598–599)

The concerns of Buckley and Lessard (2005) are shared in a recent investigation of 618 articles in four leading IB journals2 for the years 2001–2005 (Proff, 2009). The study shows that there is relatively little independent theory creation in IB and that there is a need for a sharper edge in bringing forward phenomena that challenge the ‘theoretical rocks that we stand on’ (p. 598).

Is the lack of independent theory creation a source of concern for the field of IB? We agree with Cheng et al. (2009) that the important IB phenomena requiring further theoretical clarification can only be explained by understanding the related contextual processes. This, in turn, requires the use of multiple forms of knowledge and methods, making rigorous interdisciplinarity a necessary step to advance the scientific status of the IB field, and to further its paradigm development. This is a process that requires a concerted effort able to yield a change of direction that can position the field for growth and development, showing that IB has the capabilities and the tools to demonstrate that it cannot only add value but also redefine value parameters (Shenkar, 2004).

The next section, based on recent reviews of the field, illustrates some of the emerging themes of research in this dynamic field.

Where is IB heading? Implications for international management education

At this time when, on one side, macro-environmental trends point to the heightened importance of IB research (Dunning and Lundan, 2008a) and on the other side, some scholars have expressed concern that the IB research agenda could be running out of steam, the question arises of what might emerge as the future research agenda.

After examining the scholarly work in IB over the time period 1996–2006, and defining the themes driving research over this period, Griffith et al. (2008) conducted a Delphi analysis among the most prolific IB scholars, asking them to reflect on the frontier issues that deserve future attention within the field. The results of this study are reported in Table 7.2, indicating primary, secondary and tertiary themes for future research, as judged by the respondents. The results are based upon a frequency count of respondent categorization.

| Primary themes | |

Management and performance issues in the international firm |

Cross-national market segmentation and foreign market opportunity assessment Country analysis (e.g. assessment and management of country risk) Global configuration of value adding activities Foreign market entry form (e.g. exporting, FDI, offshoring, licensing, franchising) Collaborative ventures/alliances Knowledge management and transfer Product development and innovation Global brands Relational assets in international business Supply chain management and procurement Standardization vs. adaptation Human resource management in international firms Management, strategy and structure |

|

Internationalization of firms and industries Born global companies and international entrepreneurship SMEs' experience in internationalization Managerial orientation of internationalizing firms Emergence of intermediary organizations and hybrid organizational forms Commoditization and organizational processes Integration of new technologies |

|

Focus on multinational enterprise |

Explaining the existence, strategy and organization of MNEs Multinationality of the firm and performance Regional and global MNEs Integrating mechanisms in the MNEs Global account management Contribution of the Internet and information technology to MNEs |

Globalization of economies |

Antecedents, process and consequences of globalization Empirical measurement of globalization Trade, FDI and offshoring trends Trade agreements, areas, unions The influence of non-governmental organizations on IB |

Emerging markets |

Operating in emerging markets Emerging markets' firms |

| Secondary themes | |

Multinational enterprise: subsidiary issues |

Trade-off between centralization and decentralization Coordination of MNEs' activities across subsidiaries Best-practice implementation Effectiveness of global teams |

Cultural influences/global consumer/consumption issues |

Convergence of customer demand Values towards materialism Culture and international business Regional variations in consumption Diffusion of innovations; life cycle of products |

Corporate social responsibility/MNE citizenship |

Impact of MNEs on society, local stakeholders, technology spillovers Creation of value to multiple stakeholders |

Ethical issues in international business |

Variation in ethical practices |

Public policy issues |

Unintended consequences of globalization Global poverty Environmental issues (e.g. pollution, climate change) Effects of offshoring on wages, employment and standard of living |

Methodological issues |

Better operationalization of key constructs such as global industry, global firm, global strategy, firm performance in international markets Unit of analysis in IB research International research design (e.g. country selection, sample selection, data sourcing) Rigor of methodologies employed for empirically testing IB theories |

| Tertiary themes | |

Legal aspects of international business |

Partnering across borders Conflict resolution in international partnerships Safeguarding intellectual property Security and risk issues in international business Security of employees, information, data, etc. Company response to risk (e.g. terrorism, country risk) Estimating detrimental impact of terrorism on global business |

Source: Griffith et al. (2008:1226–29).

These results clearly indicate a diversity and richness of themes, and the evolution of new perspectives of research. While the issues that are at the core of international business research such as MNEs, foreign entry market strategy and joint ventures remain of primary importance, researchers are increasingly interested in understanding the role of emerging markets in globalization, and the importance of relational assets as sources of firm competitiveness. Among the primary themes we highlight are the increasing focus on global value chains, and the challenges that arise in terms of the control and coordination of the internal and external network of activities of firms.

While in the past, comparative studies on the competitiveness of a given industry focused attention either on individual firms or on clusters, it is now acknowledged that value chain relationships play a decisive role, and that competitiveness does not concern only a single firm's performance, but that of the entire chain (UNCTAD, 2010). Linked to the management of complex value chains is the emergence of new organizational modes and governance mechanisms within the sphere of influence of the MNE (Buckley, 2011). While MNEs choose location and ownership policies so as to maximize profits, this does not necessarily involve internalizing their activities. The increasing use of contractual partnerships, for instance, is beginning to challenge our conception of the firm (Lundan, 2011a), emphasizing its coordinating role, and moving away from the pyramid-like structure of organizational hierarchy in the coordination of activity in the MNE. The control and coordination challenges arising from increasing subsidiary autonomy, and the ability of the MNE to leverage learning from multiple locations have also entered firmly on the agenda (Andersson, Forsgren, and Holm, 2007; Cantwell and Mudambi, 2005).

The fine-slicing of the activities of MNEs to many different locations has provided opportunities for new countries to enter the international arena. Emerging economies such as India and China, for instance, are now well known for subcontracting production and service activities from brand-name MNEs. Emerging economies now constitute eight of the world's 24 largest economies, and they are growing at three times the pace of the developed ones, guiding a structural transformation in the global economy. Firms from the these countries are becoming players in the global economy in their own right, and have lessons to teach concerning the strategies they have adopted (Mathews, 2006; Ramamurti and Singh, 2009). The pursuit of low-income markets in emerging economies also represents a growing area of research interest at the intersection of strategic management and IB research (London and Hart, 2004).

The role of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in international business is another emergent topic of investigation within studies looking at the impact of globalization on both developed and emerging economies. As agents of globalization, NGOs increasingly demand attention not only from governments and multilateral institutions, but also from MNEs that evaluate and assess potential foreign direct investment locations. NGOs have assumed a particularly prominent role in influencing the interaction between business and governments over the terms of international business rules, norms and practices, and especially the conditions applied to international investment projects. Host governments and MNEs must now critically assess the potential impact of nongovernmental actors on all investment plans and projects (Doh and Teegen, 2002).

Looking at the internationalization process of the firm, a phenomenon that is increasingly on the research agenda of IB scholars is that of born-global companies. Since the seminal work in which Oviatt and McDougall (1994) introduced the topic of born-global firms (which they called international new ventures), scholars have began to employ and integrate new theoretical approaches to enrich theory development concerning these types of firms. Growing consideration has been given to the international entrepreneurship approach (Oviatt and McDougall, 2005), i.e. the process of creatively discovering and exploiting opportunities that lie outside a firm's domestic markets in the pursuit of competitive advantage. At the same time, scholars have challenged the notion of large MNEs as necessarily global, rather than regionally oriented firms (Rugman andVerbeke, 2008).

Among the secondary themes, scholars have identified topics such as corporate social responsibility and ethical issues in international business (Lundan, 2011b; Scherer and Palazzo, 2011). As indicated by Dunning and Lundan (2008a: 660), ‘since the societal goals are becoming more multifaceted, and as issues related to human welfare spread beyond the material and extend to those of fairness, sovereignty, security and the environment, so the incentive structures and enforcement mechanisms initiated by, or imposed on, MNEs become a more important ingredient of their contribution to the upgrading of the human environment in which they operate’. Dunning (2010: 357) affirms that perhaps the main question in the early twenty-first century is how to best achieve the economic benefit of globalization while protecting the social needs and aspirations of local communities. The relevance of this topic for IB scholars has also been highlighted by the Academy of International Business that made the issue of IB for sustainable world development the topic of its annual meeting in 2011.

Among the emergent themes there is also the demand for more research on methodological issues. One concern which has also been the subject of a recent special issue of the Journal of International Business Studies is the overwhelming reliance on quantitative methods that have come to dominate the field of international business research. This state of affairs mirrors the broader trend towards more sophisticated quantitative empirical methods in the social sciences. It is driven both by the gradual maturation of the field of international business, and by the norms propagated within our own academic community that typically equate quantitative data with ‘hard science’ (Birkinshaw, Brannen and Tung, 2011).

While there are clear merits associated with quantitative methods, the multicultural, multidimensional and dynamic nature of the field of international business lends itself to many different research methodologies — including qualitative methods (Marschan-Piekkari and Welch, 2004). In order to appreciate the relative newness of some of the topics under investigation in international business, and to understand the complexities related to them, it is often inappropriate to engage in large sample studies or reductionist methods (Cantwell, Dunning and Lundan, 2010). Rather, thick description, exploratory research and comparative analysis that focuses on theory building and hypotheses generation may be more suitable.

As tertiary topics, the researchers indicated legal aspects of international business and intellectual property issues, in particular exploration into the effectiveness of contract-based versus informal cross-border partnerships, a subject which is very topical considering the increasing number of cross-border partnerships and the issue of long-term governance of these long-term relationships (Calliess and Zumbansen, 2010; UNCTAD, 2011). Another new thrust of international business research is in the area of security and terrorism (Suder, 2004). Indeed scholars and policy makers have long expressed interest in the relationship between the global economy and political conflict (Henisz, Mansfield and Von Glinow, 2010). The opinions are divergent, and while some observers sustain that the growth of international exchange promotes peace, others argue that higher economic interdependence can contribute to the degradation of interstate relationships through acts of terrorism by non-state actors and spur interstate conflict. Other scholars doubt that any systematic relationship exists between economic exchange and hostility. Emerging research is trying to unpack country-level, sector-level and firm-level contingencies that affect the strength and nature of the relationships between conflict and economic exchange (Mansfield and Pollins, 2001).

The above review of some of the emerging themes, however limited, confirms that there is a richness of topics to be investigated, and that far from running out of steam, the ‘future agenda of international business is set to be one of the most intellectually challenging, but potentially fruitful, of all the social science disciplines in the next two or three decades…because it is in a privileged and unique position to explore the interaction between corporations and the changing cross border physical and human environment in which they operate; and its implications for global economic welfare’ (Dunning, 2006: 3).

Conclusion

This chapter has analysed the discipline of IB by examining its conceptual domain, the evolution of the field over the years, the main criticisms it is facing and the emerging themes of investigation.

Having defined IB as a field of inquiry concerned with the study of enterprises crossing national borders, we identified integration and interdependence as two core characteristics of IB. The former refers to the interdisciplinary nature of IB and the need for scholars to combine knowledge from different disciplines or functional areas of business in order to understand the deeply embedded and contextual processes being studied. The latter has to do with the relationship of the firm with the dynamic external environment in a dyadic process of adaptation and co-evolution (Cantwell, Dunning and Lundan, 2010). MNEs both contribute to and are affected by the contagion effects arising from the external environment that are now capable of being transmitted more rapidly and effectively from one place to another.

Looking at the evolution of the IB field, we showed that there has been a progression from an initial focus on the macro-environmental issues that impact on the MNE, to a more recent emphasis on micro-economic, firm-level issues and a renewed interest in various aspects of the human environment. Growing attention is now being given to the role of institutions and their underlying values in affecting the motives for and patterns and mode of IB operations and MNEs' strategies. Methodologically, while the theories borrowed from outside IB may sometimes be superficially understood, badly applied and inappropriately interpreted, we consider that the use of multiple forms of knowledge and methods is a necessary step to advance the scientific status of the IB field and to further its paradigm development.

The emerging themes of investigation we reviewed increasingly require scholars to build on insights gained from other disciplines, pushing the frontiers of the field. We believe that the future of the IB field lies in an open and collaborative effort in which scholars from various disciplines who have an interest in MNEs, mixing different assumptions, causal mechanisms and levels of analysis, can help to gain insights in order to help MNEs to design more effective corporate strategies and to assist policy makers in designing adequate public policies.

Notes

1 Journal of International Business Studies, Management International Review, Journal of World Business, International Marketing Review, Journal of International Marketing, International Business Review.

2 Journal of International Business Studies, International Business Review, Management International Review, Journal of World Business.

Bibliography

Aharoni, Y. 1966. The foreign investment decision. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

Andersson, U., Forsgren, M., and Holm, U. 2007. Balancing subsidiary influence in the federative MNC: a business network view. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(5): 802–18.

Bartlett, C. A. and Ghoshal, S. 1989. Managing across borders; the transnational solution. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Birkinshaw, J., Brannen, M.Y., and Tung, R.L. 2011. From a distance and generalizable to up close and grounded: Reclaiming a place for qualitative methods in international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 42: 573–81.

Buckley, P. J. 2002. Is the international business research agenda running out of steam? Journal of International Business Studies, 33(2): 365–73.

Buckley, P.J. 2011. International integration and coordination in the global factory. Management International Review (MIR), 51(2): 269–83.

Buckley, P. J. and Casson, M. 1976. The future of the multinational enterprise. London: Holms and Meier.

Buckley, P. J. and Casson, M. 1998. Models of the multinational enterprise. Journal of International Business Studies, 29(1): 21–44.

Buckley, P.J. and Lessard, D. 2005. Regaining the edge for international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 36(6): 595–99.

Calliess, G.-P. and Zumbansen, P. 2010. Rough consensus and running code: a theory of transnational private law. Oxford: Hart.

Cantwell, J., Dunning, J.H., and Lundan, S.M. 2010. An evolutionary approach to understanding international business activity: the co-evolution of MNEs and the institutional environment. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(4): 567–86.

Cantwell, J. A. and Mudambi, R. 2005. MNE competence-creating subsidiary mandates. Strategic Management Journal, 26(12): 1109–28.

Caves, R.E. 1971. International corporations: the industrial economic of foreign investment. Economics, 38: 1–27.

Caves, R. E. 1998. Research on international business: problems and prospects. Journal of International Business Studies, 29(1): 5–19.

Cheng, J.L.C., Henisz, W.J., Roth, K., and Swaminathan, A. 2009. From the editors: advancing interdisciplinary research in the field of international business: prospects, issues and challenges. Journal of International Business Studies, 40: 1070–74.

Daniels, J. 1991. Relevance in international business research. A need for more linkages. Journal of International Business Studies, 22: 177–86.

Doh, J.P. and Teegen, H. 2002. Nongovernmental organizations as institutional actors in international business: theory and implications. International Business Review, 11(6): 665–84.

Dunning, J.H. 1977. Trade, location and economic activity and the multinational enterprise. In Ohlin, B., P.O. Hesselborn, and P.M. Wijkman (eds), The international allocation of economic activity. London: Macmillan.

Dunning, J. 1979. Explaining changing patterns of international production. In defense of the eclectic theory. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 41(4): 269–95.

Dunning, J.H. 1980. Toward an eclectic theory of international production: some empirical tests. Journal of International Business Studies, 11: 9–31.

Dunning, J.H. 1989. The study of international business: a plea for more interdisciplnary approach. Journal of International Business Studies, 20: 411–36.

Dunning, J.H. 2006. New directions in international business research. AIB Insights, 6(2): 3–9.

Dunning, J.H. 2010. New challenges for international business research. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Dunning, J.H. and Lundan, S.M. 2008a. Multinational enterprises and the global economy, second edition. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Dunning, J.H. and Lundan, S.M. 2008b. Institutions and the OLI paradigm of the multinational enterprise. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 25(4): 573–93.

Eden, L. 2008. Letter from the editor-in-chief. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(1): 1–7.

Eden, L. and Lenway, S. 2001. Multinationals, the Janus face of globalization. Journal of International Business Studies, 32(3): 383–400.

Fruin, W.M. 2007. Bringing the world (back) into international business. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(2): 353–56.

Griffith, D. A., Casvugil, S. T., and Xu, S. 2008. Emerging themes in international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 39: 1220–35.

Henisz, W.J. 2000. The institutional environment for international business. Journal of Law, Economics and Organization, 16(2): 334–62.

Henisz, W.J. 2005. The institutional environment for international business. In Buckley, Peter J. (ed.), What is international business? Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan.

Henisz, W.J., Mansfield, E. D., and Von Glinow, M. A. 2010. Conflict security and political risk: international business in challenging times. Journal of International Business Studies, 41: 759–64.

Hymer, S.H. 1976. The international operations of national firms: a study of direct foreign investment. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Johanson, J. and Vahlne, J.-E. 1977. The internationalization process of the firm — a model of knowledge and increasing foreign commitments. Journal of International Business Studies, 8: 23–32.

Johanson, J. and Wedersheim, P. 1975. The internalization process of the firm — four Swedish cases. Journal of Management Studies, 12: 305–22.

Jones, G. and Khanna, T. 2006. Bringing history (back) into international business. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(4): 453–68.

Kindleberger, C. (1969). American Business Abroad. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Lall, S. 1980.Vertical interfirm linkages in LDCs: an empirical study. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 42(3): 203–26.

Lewin, A.Y. 2004. Letter from the editor. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(2): 79–80.

London, T. and Hart, S.L. 2004. Reinventing strategies for emerging markets: beyond the transnational model. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(5): 350–70.

Lundan, S.M. 2011a. The coevolution of transnational corporations and institutions. Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, 18(2): 639–63.

Lundan, S.M. 2011b. An institutional perspective on the social responsibility of TNCs. Transnational Corporations, 20(3): 61–77.

Mansfield, E.D. and Pollins, B.M. 2001. The study of interdependence and conflict: recent advances, open questions and directions for future research. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 45(6): 834–59.

Marschan-Piekkari, R. and Welch, C. 2004. The handbook of qualitative research methods in international business. London: Edward Elgar.

Mathews, A.J. 2006. Dragon multinationals: new players in 21st century globalization. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 23: 5–27.

North, D.C. 1990. Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

North, D.C. 2005. Understanding the process of economic change. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Oviatt, B.J. and McDougall, P. P. 1994. Toward a theory of international new ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, 24(1): 45–64.

Oviatt, B.J. and McDougall, P. P. 2005. Defining international entrepreneurship and modelling the speed of internationalization. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(5): 537–54.

Peng, M. W. 2004. Identifying the big question in international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(2): 99–108.

Proff, H. 2009. Research in the field of international business — insufficient independent theory creation? IAM-Papers on International (Automotive) Management. Duisburg Universität Duisburg-Essen.

Ramamurti, R. and Singh, J. V. (eds). 2009. Emerging multinationals in emerging markets. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Redding, S.G. 1994. Comparative management theory: jungle, zoo or fossil bed?. Organization Studies, 15: 323–60.

Rugman, A.M. and Verbeke, A. 2008. The theory and practice of regional strategy: a response to Osegowitsch and Sammartino. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(2): 326–32.

Scherer, A.G. and Palazzo, G. 2011. The new political role of business in a globalized world: a review of a new perspective on CSR and its implications for the firm, governance and democracy. Journal of Management Studies, 48(4): 899–931.

Scholhammer, H. 1994. Strategies and methodologies in international business and comparative management research. Management International Review, 34: 5–21.

Sharma, D. 1992. International business research: issues and trends. Scandinavian International Business Review, 1(3): 3–8.

Shenkar, O. 2004. One more time: international business and global economy. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(2): 161–71.

Stopford, J. 1998. Book review of International business: an emerging vision. Journal of International Business Studies, 29: 635–37.

Streeten, P. 1972. Multinational enterprises and nation state. The Frontiers for Development Studies: 67–93. London: Macmillan.

Suder, G.G.S., (ed.). 2004. Terrorism and the international business environment: the security—business nexus. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Sullivan, D.P. 1998. The ontology of international business: a comment on international business: an emerging vision. Journal of International Business Studies, 29(4): 877–86.

Sullivan, D.P. and Daniels, D. 2008. Innovation in international business research: call for multiple paradigms. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(6): 1081–90.

Thomas, A., Shenkar, O., and Clarke, L. 1994. The globalization of our mental maps: evaluating the geographic scope of JIBS coverage. Journal of International Business Studies, 25: 675–86.

Toyne, B. and Nigh, D. 1998. A more expansive view of international business. Journal of International Business Studies, 29(4): 863–76.

UNCTAD. 2010. Integrating developing countries' SMEs into global value chains. New York and Geneva: UNCTAD.

UNCTAD. 2011. World Investment Report 2011. Non equity modes of international production and development. Geneva and New York: UNCTAD.

Vernon, R. 1966. International investment and international trade in the product cycle. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 80: 190–207.

Vernon, R. 1974. The location of economic activity. In Dunning, J. (ed.), Economic analysis and the multinational enterprise. London: George Allen and Unwin.

Vernon, R. 1994. Contributing to an international business curriculum: an approach from the flank. Journal of International Business Studies, 25: 215–28.

Wright, R. W. and Ricks, D. A. 1994. Trends in international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 25(3): 687–701.