27

DEVELOPING SUCCESSFUL

INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS

Meeting the requirements of entrepreneurial

ventures and their business environments

Rosalind Jones and Richard Edwards

Introduction

This chapter informs discussions on international management education (IME) and contributes business insights from the serial entrepreneur's perspective. A case study of an internationalizing high-growth technology company is reported along with insights based on the experiences of an intrepid entrepreneur who has created a new technology venture and achieved rapid growth in international markets. His experiences of simultaneously undertaking a Masters in Business Administration (MBA) executive degree program together with starting a new business, enables examination of business models traditionally taught on MBA programs and provides thought-provoking critical insights into the usefulness of such models in the entrepreneurial, internationalizing firm context. Relevance of other useful topics for the MBA program is also proffered and reflections as to the order of delivery of modules on programs are extrapolated.

In particular, this chapter examines the differences between the sorts of management tools/ models required for large and small firms, particularly in respect of the issues of the small business and in the light of the findings of researchers (e.g., Casson, 1982) who found that entrepreneurs are both decision makers and coordinators. The case study is also underpinned by contextual literature relating to the growth and support of new, entrepreneurial technology firms in north Wales, UK. Unlike larger firms, in general, new ventures and small businesses face much greater challenges in the marketplace and suffer inherent business constraints such as limited resources which may include lack of finance and limited business and/or marketing expertise (Carson et al., 1995).

In this case, the entrepreneur readily identifies other intriguing less recognized constraints for the small firm which impact on the growth potential of the firm in contemporary settings. These include the issue of geographical remoteness (rurality) and, the significance of developing mutual trust with stakeholders. Hence, this study describes IM for small entrepreneurial firms focusing on the importance of effective relationships with stakeholders upon which the technology firm is incumbent and includes discussion on the use of resource leveraging, mergers and acquisitions, competition and rules of engagement, with technology in particular optimizing rules of engagement. In addition, the entrepreneur describes his firm's swift growth and the managerial issues surrounding this growth. In so doing, the authors reflect on whether present prescribed models fit. Using this case study and examples and experiences from this case study, a new model is developed and proposed which explores and identifies the managerial issues for the entrepreneur of a high-growth internationalizing firm. This model differs significantly from those often presented to business students.

First, the chapter begins with the introduction of established business strategy models traditionally taught to budding business students across the globe. Second, the case study and context of the case study are presented and is used to demonstrate the current strategic management issues for the nascent entrepreneur of a high-growth technology firm. Then, traditional models are described and critiqued in the light of increased global competitiveness and entrepreneurial activity, and new approaches for IME are proposed based on developing IME theory in relation to the entrepreneurial firm context. Such new approaches will address the need for leveraging of resources and identification of and engagement with stakeholders and illustrate new rules of engagement. A new business strategy model for internationalizing entrepreneurial ventures is proposed. The model identifies illustrates a non-linear, irregular growth trajectory and also internal management issues relating to swift growth which underpin firm performance, together with the positive and negative influences of stakeholders. The chapter concludes by summarizing the benefits of new approaches to teaching business.

Both authors have experience being MBA students on executive programs. Both have achieved excellent results on the programs and in their entrepreneurial and academic ventures while thoroughly enjoying these experiences. Yet, the realities of creating a high-growth startup company and managing the firm growth trajectory are very different from classroom-based traditional business strategy models.

Entrepreneurial business growth: direct and indirect business support in Wales

This section first explores key issues surrounding the development and support of technology-based firms in north-west Wales, UK. It provides insights into direct and indirect support that technology entrepreneurs attempt to access, in order to ensure the growth of their business. Research of technology firms in this context is important as there is limited research in Wales, and also it provides useful insights into requirements for the development, growth, and sustainability of technology firms which operate in deprived regions.

The impact of public policy on innovative small to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and development of regions is of global interest (Acs, 1999; Eshima, 2003; OECD, 1997; USGAO, 1998). In the UK, grants schemes and business support were available in “qualifying areas,” but now under the recently launched “Solutions for Business,” SMEs are able to apply for grants in all areas of the UK. Known as Grant for Business Investment (GBI) in England and Scotland, and in Wales the Single Investment Fund (SIF), this grant is part of a package of funding introduced by Business Innovation and Skills (BIS) (Business Innovation and Skills, 2011) while Enterprise Ireland offers a comprehensive range of support for northern and southern technology businesses, entrepreneurs, and high potential start-ups (Enterprise Ireland, 2011).

The north-west Wales region attracts European Social Funding (Convergence funding) as it is designated as an area of social and economic deprivation. Within this region are technology parks and clusters of incubator and more established, technology-based firms, some parks being funded via the Technology Strategy Board, which operates across England and the devolved governments of Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales (Technology Strategy Board, 2011). Despite acknowledgement of the importance of technology firms to regional economies (Harris, 1988; Keeble and Kelly, 1988), little is understood about the challenges faced by technology entrepreneurs. Technology-based firms are noted for experiencing difficulties in leveraging their own innovative products in the marketplace as well as having very limited access to finance (Harrison et al., 2004; Hausman, 2005). Although researchers have explored the role of university incubator firms and networks (Perez and Sanchez, 2003; Steffensen et al., 2000), and the importance of geographically situated incubation units in relation to stimulation of innovation and entrepreneurial activity (Hendry et al., 2000; Rothwell and Dodgson, 1992), there is a paucity of research in terms of availability and access to business support. Storey and Tether (1998) reviewed public policy measures aimed at supporting new technology-based firms (NTBFs) in the following areas: science parks; supply of PhD students; relationships between NTBFs and universities; direct government financial support, and; the impact of technology advisory services on NTBFs. Such discussions (Jones and Parry, 2011) facilitate greater understanding of nascent and existing entrepreneurs in technology industry sectors and also explore informal aspects of business support and entrepreneurial activity which may integrate with other, more formal measures of support. Arguably as this chapter and case study suggest, the opportunity for entrepreneurs to access business degree programs is of acute benefit and may be included as a way in which technology entrepreneurs (or indeed other entrepreneurs and business students) are able to develop new businesses and will help them work effectively with direct and indirect support that they can access throughout the business development process.

The intrepid entrepreneur and the case study firm

Richard is Managing Director of the NMi group's UK office, which provides regulatory compliance testing and security auditing to manufacturers, operators, and regulators across the international gaming industry. NMi's UK office has become the leading ISO/ICE 17025:2005 accredited test house for compliance testing against the UK Gambling Commission's Technical Standards and has subsequently expanded its operations internationally following similar approvals by the Alderney Gambling Control Commission (AGCC), the Jersey Gambling Commission, the Spanish National Gambling Commission (CNJ), the Government of Gibraltar Licensing Authority, the Malta Lotteries and Gaming Authority (LGA), the Isle of Man Gambling Supervision Commission (GSC), Loto-Québec, and the Kahnawake Gaming Commission (KGC).This portfolio of territories, popular as licensing bases for gaming companies offering online gaming, adds to the NMi group's existing jurisdictional coverage across mainland Europe.

Richard and his co-director created this company following work at Bangor University and prior to this he was architect and technical manager for systems development at Semantise Ltd, another company of which he was co-founder and which is still successfully operating today. Semantise Ltd is the leading UK reseller of Open Text's “FirstClass” communications platform and the company has developed a range of complementary products and services for the education sector, including reporting software and administrative applications for local authorities and schools.

This chapter focuses specifically on a single case study: the development and establishment of Richard's testing and auditing company.

Entrepreneurs and regional community benefits

The definition of entrepreneurship has evolved into a complex set of ideas, yet may be defined as “the process of uncovering or developing an opportunity to create value through innovation” (Macke and Kayne, 2001). Innovation is closely intertwined with entrepreneurship with the creation of new ideas or products that can provoke change. The entrepreneur influences the firm, driving innovative activity or creativity of ideas (Carson et al., 1995; Hills et al., 2008). The benefit of such entrepreneurial activity to regional communities is of global interest, with both central and regional governments acknowledging the value of innovative entrepreneurs. Small entrepreneurial firms contribute to job creation, vital in deprived economies, and may grow into large firms. The earnings of self-employed entrepreneurs are also a driver, as they are almost one-third higher than the earnings of salaried employees (Devine, 1994).

Researchers have identified two types of entrepreneurs: lifestyle entrepreneurs, who add value to their community and have low-growth firms, and those entrepreneurs who are typically motivated to start and develop larger, more visible and more valuable firms, as in the case of this entrepreneur and this case study company. Typically these types of entrepreneurs seek resources that will help them grow. This group is defined as creating more economic benefit for their communities, creating more jobs, with entrepreneurial philanthropic approaches creating additional investment in community projects (Schindehutte et al., 2009). When these benefits outweigh the costs of supporting high-growth entrepreneurs, investing more into new entrepreneurial ventures is considered to be a sound strategy for adding economic value to regions (Henderson, 2002).

SMEs and technology transfer

In the 1970s new innovation policies emerged from the United States. Alongside research and development (R&D) it was acknowledged that the commercialization of new products required other means of support (Rothwell and Dodgson, 1992). Innovation policies included grants for innovation, the involvement of collective research institutes in product development and innovation-stimulating public procurement. However, a continuing lack of venture capital prevailed. In the 1980s there was increased stimulation of university—industry linkages. Technology policies now included selection and support of generic technologies, growth in European policies of collaboration in pre-competitive research, and emphasis on inter-company collaboration. At this point government focus shifted to the creation of NTBFs and on increasing the availability of venture capital (Rothwell and Dodgson, 1992).

Technology SMEs provide significant sources of innovation and are a powerful means for growth and development in regional economies (Cooper and Park, 2008). Researchers highlight the importance of supporting innovative technology firms in Wales (Hendry et al., 2000; Huggins, 1996).Westhead and Storey (1994) found that the supply of highly qualified technology entrepreneurs who were “leading edge” was an important and necessary function of universities. Knowledge Transfer Partnerships (KTPs), funded by the Technology Strategy Board, have been introduced between universities and SMEs (Technology Strategy Board, 2011). Under this scheme postgraduate or doctoral students are placed in SMEs to encourage innovation and improve the capability of the business. Many companies have benefited from KTP investments, and such projects improve linkages between academia and enterprise (Harris, 1988).

Policy support for technology-based firms

In the current economic climate there is likely to be a renewed focus on accountability and evaluation measures for public R&D policies, with the accelerated establishment of science parks and innovation centers across the UK. For example, The Technology Strategy Board operate UK wide while Intertrade operate the FUSION program, a university and business collaboration across Ireland from north to south (Enterprise Ireland, 2011). Despite such activities, there is still concern about regional disparities and an obvious requirement for focusing on less developed regions. Indeed, Westhead and Storey (1994) observed that science park location does not significantly influence growth and survival of NTBFs but it may stimulate the formation of firms which would not otherwise have been established and constitutes an economic “magnet” for the clustering of technology-based firms which enhances local economic development (Bartels and Wolfe, 1993; Storey and Tether, 1998; Van Tilburg and Vorstman, 1994).

Direct and indirect business support

Storey and Tether (1998) identified two types of support: direct support in the form of financial loans, grants, guarantees, tax relief, etc., and indirect support provided in the form of access to information, business advisory services, etc. There is limited research in respect of success and failure pathways for those start-ups that access grants or business loans from banks or other financial institutions. Such reported findings suggest that there are many contributing factors towards business failure, and success (Fielden et al., 2000; Reid and Smith, 2000). In the UK, direct business support is primarily delivered through national government schemes and in Wales via the Welsh Assembly Government (WAG). WAG provides financial support via SIF and Finance Wales to create, sustain and help grow new businesses in Wales (Welsh Assembly Government, 2011) Government in Wales also provides advisory and other business services using intermediaries such as Flexible Service for Business (FS4B) and Venture Wales. Other, smaller grants are available to SMEs in Convergence funding areas and WAG also offers specialist support to the technology industries through its Technium network, which provides incubation facilities to knowledge-based technology businesses in Wales (Welsh Assembly Government, 2011).

Indirect forms of support include business advisors, consultants, accountants, banks, university collaborations, and networks (Berry et al., 2006; Gibb, 2000; Ramsden and Bennett, 2005). With north-west Wales designated as a Convergence region, the expectation may be that new businesses face additional challenges at start-up and may rely more heavily on public sector support for development and growth. Therefore problems reported about the quality and consistency of public sector support provision should be noted (Ramsden and Bennett, 2005). However, a recent report by the Forum of Private Businesses (2010) showed that businesses believed that public sector support services such as Business Link advice should be retained or increased despite the current economic climate.

Technology SMEs: business issues and limitations

Innovativeness in SMEs tends to be generated more readily due to their smaller and flatter organizational structures, the absence of bureaucracy, and knowledge sharing and collaboration (Laforet and Tann, 2006). SMEs are also flexible and can respond rapidly to environmental needs and customer preferences by working closely with their customers. Challenges for SMEs include difficulty in making an impact in large, competitive markets with established players; therefore, they create new markets by developing an innovative product or service, or commit to supplying a neglected, untapped niche market. Both paths can provide them with the opportunity to create competitive advantage (Carson et al., 1995; Hill, 2001). Furthermore, SMEs cannot compete in the traditional sense, as they have limited resources and cannot achieve economies of scale; therefore, entrepreneurs often leverage additional resources using networks and develop core competencies in order to achieve a competitive advantage (O'Donnell et al., 2002). SME researchers have identified problems inherent in most small firms (Carson et al., 1995; Hill, 2001; Simpson and Taylor, 2002). These include lack of resources, limited finances, a lack of strategic expertise, and the fact that the power and decision-making is concentrated solely in the entrepreneur (Chaston, 1997; Hausman, 2005).

Small technology ventures tend to be managed by technical specialists rather than business or marketing experts who often have a limited customer base and limited access to competitive markets. It is also difficult for SMEs to gain credibility in a highly competitive, rapidly evolving and uncertain market (Mohr, 2001). Berry (1996) found technology-driven companies to be least successful in terms of corporate performance, highlighting the need for technology SMEs to move from a technological posture to a marketing-led company. Other challenges in new product development (NPD) projects in technology SMEs include project visioning, communication, and management support (Akgun et al., 2004), and the issue of improvement in NPDs to differentiate the product from others on the market. Hence, there is a need for MBA programs to include effective marketing and business modules on their programs.

Entrepreneurial networks, business alliances, and relationships

The entrepreneur's use of networks and Personal Contact Networks (PCNs) is noted as essential for small entrepreneurial firms; networking being an instinctive entrepreneurial activity which increases business knowledge, access and the sharing of resources and identification of new opportunities (Gilmore et al., 2001; O'Donnell, 2004; Tersvioski, 2003). Partnerships and alliances are also commonplace in technology SMEs where cooperation with a larger, trustworthy actor in the market is the key to strengthening SME marketing strategy (Ojasalo et al., 2008). Alliances and network relationships are also vital for sharing innovation and marketing resources and increasing the technology firm's general business capacity (Jones and Rowley, 2009). The effectiveness of the firm is often largely based on how the entrepreneur leverages additional resources for the firm, factors identified in the SME marketing and entrepreneurial marketing literature (Carson et al., 1995; Collinson and Shaw, 2001). Related studies of networking in technology industries have also highlighted the importance of locally embedded networks, which supports the development of high-tech regional clusters (Hendry et al., 2000; Van Geenhuizen, 2008).

Use of current business models for educating nascent entrepreneurs

Richard and another colleague, subsequently to become co-founder of the testing and auditing company, began the MBA executive program while working at Bangor University on knowledge transfer projects, and with a view to gaining a more formal foundation for their business knowledge and entrepreneurial attitudes. It was only later that the pair decided to form a company, but the decision was made prior to completing the program. In the writing of this chapter Richard has reflected on the usefulness of the MBA program for entrepreneurs. Some modules were inevitably more relevant than others, and these included business planning and financial accounting for managers. Most notably these were, for new entrepreneurs at least, in the incorrect order from the point of view of practical implementation in a fledgling company. This is a point of interest for degree program planners to take note and consider the “step-by-step” process that may be needed when teaching IME to entrepreneurs. For example, business planning and financial management would be more useful to new business owners if delivered early in the MBA program as, while the business is being formed, project funding applications, business plans, and financial plans are required to be written; in short, there is an argument to be made that the modules in an MBA program should be ordered to correspond with real business lifecycles. Furthermore, having business and financial experts to hand at these critical points of new venture development would inevitably facilitate business creation. Equally, teaching and learning on Master's programs with the emphasis on early internationalization into new and emerging markets would facilitate steeper growth trajectories for new start-up companies and encourage wider thinking in terms of where the entrepreneur should seek business opportunities in global markets and move away from the assumption that new businesses develop local markets first and only seek to secure international and cross-border market opportunities later.

Most business strategy books suitable for both undergraduate and postgraduate students use traditional modes of teaching business strategy implementation. Interestingly, in Richard's experience, no particular core module focused on internationalization or international business strategies, perhaps a fact of concern in the entrepreneurial firm context. Hence, business students are reliant on theoretical discussions currently adopted in business strategy books include exploration of the macro-environment using PESTEL analysis, assessment of the competitive environment using the five forces model (Porter), and analysis of the industry using industry life-cycle models. Subjective assessment of competitors and markets includes identification of strategic groups and market segments and assessment of opportunities and threats in markets. Strategic capabilities of the firm are also acknowledged as relevant in formulating suitable strategies and include aspects such as use of the value chain and value networks, benchmarking, and SWOT analysis. Other managerial factors are also considered such as corporate social responsibility (CSR), management style, for example, laissez-faire, stakeholder interaction, stakeholder mapping, and values, mission, vision, and objectives. Also included under strategic capabilities are the effect of culture and strategic drift with use of models such as the strategy clock and price and differentiation strategies, strategic direction, market penetration and consolidation, and product/market developments (Ansoff's Matrix). Also prevalent is the use of predictive models such as the Boston Consultancy Group (BCG) directional policy growth/ share matrix and the General Electric (GE)-McKinsey directional policy matrix (Johnson et al., 2009).

International business strategy researchers refer to such models as Porters National Diamond, International Value Networks, Market Selection and Entry Modes, Market Characteristics, and competitive characteristics. Strategic methods and evaluation include pursuing of certain strategies, organic development of the firm, mergers and acquisitions, evaluation of strategies, suitability, acceptability, and feasibility. In terms of managerial action this may include the functional structure of the firm, the multidivisional structure, and the matrix structure of the firm. Organizational processes are also considered and include direct supervision, planning processes, cultural processes and performance, and market-targeting processes. International business books also include the complexities of managing strategic change, managerial styles, and levers for managing change. These are detailed and wide-ranging literatures which address both internal management factors relating to international business strategy and external factors such as evaluation of cross-border markets and strategic choice. In the life of a technology start-up and in the experiences of an entrepreneur, in a small entrepreneurial firm seeking high growth in volatile markets, the managerial experience is very different.

There are, of course, business strategy books for SMEs. Karami (2007) and Analoui and Karami (2003) describe the dominant paradigm in strategic management as a prescriptive, rational, and analytical model characterized by two principal functions: strategy formulation and implementation. Such views are also held by Ansoff (1965), Andrews (1986), and Porter (1979, 1980) (cited in Karami, 2007). Karami observes that strategic formulation is how the firm chooses to define strategy and how it approaches implementation through strategic management (Collins, 1995; Bowman, 1998). Strategy may be formal and rational (Mintzberg, 1994 (cited in Karami, 2007)), emergent and progressive (Whittington, 1993) with a logical or incremental

Figure 27.1 Universal and entrepreneurial competence: sourced from Sandler-Smith et al. (2003)

path. Karami observes that it is different in entrepreneurial firms, saying that the approach to strategy formulation dictates the eventual management style.

A review of the entrepreneurial management literature provides models which have some resonance with regard to some of the issues that we have proffered. Sandler-Smith et al. (2003) researched both entrepreneurial and non-entrepreneurial small firms and found similarities and differences in relation to formalizing and undertaking managerial tasks. There was a common need to manage certain aspects of their organization's activities; namely functional roles involving responding to environmental change and achieving performance goals. Such entrepreneurial firms, however, also identified the additional roles associated with working with employees in the effective management of the firm's vision and culture (Figure 27.1). Certainly in recounting Richard's experiences, while the focus of the firm is on internationalizing and market expansion, there is a strong focus and awareness of ensuring internal processes and procedures are adapted and maintained in order to cope with new customer demands and that HRM policies and practices reflect that. Recruitment of the right staff is also very important and gauging the correct level of expertise and knowledge to match the firm's expansion. Some flexibility is ensured with “freelancing” international employees based in other countries.

There have been various stages and growth models relating to new businesses (Churchill and Lewis, 1983; Grenier, 1998). A more recent and appropriate model presents the firm life-cycle concept (Chaston, 2010), suggesting that at specific points on the life-cycle curve, small firms face a new chasm which has to be crossed before the next stage of growth can commence. Crossing the chasm will usually require the entrepreneur to acquire new management skills as well as being prepared to revise the priorities being allocated to specific managerial tasks (Figure 27.2).

At the pre-start-up stage, the focus of the entrepreneur is on deciding whether the business is viable. Activities may include sourcing business support (financing), assessing market potential,

Figure 27.2 Growth and chasms model, sourced from Chaston (2010): 1. Launch; 2. Capacity expansion; 3. Organizational formalization; 4. Succession; 5. Long-term growth

or feasibility of a new technology. The time between deciding to enter an industry and launching the business can range anywhere from a few months to several years (Beverland and Lockshin, 2001). It is expected that at this stage some entrepreneurs will decide not to progress the business. Usually reasons are the inability to gain financial backing or being unable to develop a commercially viable version of the new technology which is being developed. A failure to achieve a key aim such as the technology not proving viable will mean the business will not manage to get across Chasm 1 (Dunn and Cheatham, 1993). Richard and his co-director were at this stage having to work through complex and difficult funding applications, in particular, bank loans and government support which would allow for employee recruitment.

The next start of the business phase is where the primary focus is on identifying customers and generating initial sales (Luger and Koo, 2005). Should there be a lack of customers then Chasm 2 will not be crossed. During the subsequent capacity expansion stage, the entrepreneur's attention will usually need to be focusing on finding ways to satisfy rising demand for the product. In the high-technology service sector this may mean investing in new servers and associated data-processing systems in order to handle rapidly rising numbers of customers. Failure to meet demand with supply will mean a failure to cross Chasm 3. In GMS (then NMi in 2010) Richard's team were at this point not just waiting for website traffic but actively writing and submitting complex gaming applications (often in different languages) to capture new business in new countries. Chasm 4 describes the need for the entrepreneur to establish a more formalized organizational structure because the workload for one person will eventually become too much. Typically this involves hiring or promoting staff to become responsible for functional activities such as marketing, production management, and finance. A failure to implement these changes means that the business will not cross Chasm 4. Chasm 5 relates to the stage at which there is long-term growth and succession planning is required. At the point of Chasm 4 and Chasm 5, the model becomes too prescriptive for this technology case study. Technology companies often attract outside investment or are bought out; there is also a pattern in technology sectors of alliances, partnerships and mergers (Jones and Rowley, 2009). The likelihood of succession planning for technology sector SMEs is difficult to predict as it demands highly sophisticated technological knowledge and skills and perhaps may be more likely to be sold off or merged with another technology company.

So, we see that there is an established platform of theoretical developments derived from empirical research which explain traditional methods of business strategy in large and SME firms. International strategic management is described by Griffin and Pustay (2005: 309) as follows: “to enable a firm to compete effectively internationally” as referred to by Eden et al. (Chapter 4, this book). Actual strategy in action includes functional structure, multidivisional structure, and consideration of organizational processes including direct supervision, planning processes, cultural processes, and performance-targeting processes, along with marketing processes and also then managing strategic change, roles in managing change of style of managerial change, and levers for managerial change (Johnson, Scholes and Whittington, 2009)

All these aspects are very difficult to achieve in a new business start-up or even in an established technology SME, as will be explained further in this chapter which goes on to explore traditional business models and provides thought-provoking critical insights into the usefulness of such models in the entrepreneurial, internationalizing firm context.

Planning, strategy formulating, and competitive strategies in NMi

The following section uses the case study to illustrate the key managerial issues facing the nascent entrepreneur in developing a high-growth, internationalizing, technology firm.

How the firm started and grew: the industry and its markets

The company commenced trading as GDS Laboratories Ltd in 2009 and joined the NMi group in 2010. Operations outside of the UK commenced in 2010, but these were in earnest from 2011. The company's stakeholders were as follows: the founder Directors; the bank (the company was largely debt financed); the Welsh Government (a grant for initial employment costs). Later, stakeholders included the NMi group and its parent companies (Holland Metrology B.V., a holding company for NMi and other metrology companies, and TNO Companies B.V., its parent). TNO is a “knowledge transfer” company, created and supported by Danish government funding and has no shareholders. It exists primarily to develop and commercialize R&D activities in the Netherlands.

NMi, the case study company, started business initially in the UK only, and then targeted English-speaking jurisdictions, those which were geographically close and culturally close. These markets were in the Isle of Man and Alderney, with the “online” jurisdictions that can be served remotely (from the UK) first, then those requiring some physical presence and not necessarily English speaking (e.g., Spain, where the company has representatives on the ground there).

Richard describes this as the “low-hanging fruit,” looking for profitable business abroad, needing a portfolio of jurisdictional approvals; in some you need legal representation and language experts—we open offices or recruit agents if needed (but the situations differ in different countries).

Rurality

NMi is based in the “Welsh Heartlands” in a geographically remote region. This area being remote from large cities and airports. NMi is located on a small technology park with several technology companies nearby and a culture of technology in the direct area. However, this is very small. Links to the university create opportunities in terms of potential KTPs and computer engineering students. The main issues which impact on this entrepreneurial firm are first the recruitment of suitably skilled candidates for job vacancies within the firm. Candidates generally have to have a high level of knowledge and experience in software development. However, on the plus side, once a person is recruited, the retention of employees has been good. This is because the company tries to be a good employer and is able to pay higher wages than other employers in the area, and there is little localized competition and demand for technology jobs. Also, those working in the area have tended to make a “lifestyle choice” and live in an area of outstanding natural beauty.

Richard describes the difficulties of reaching the markets he has described. For example, visiting Malta several times for one of his employees was particularly arduous in winter. Not only is it a long journey to the nearest airport requiring a taxi early in the morning, but a complex change of flights is needed to get to Malta out of the tourist season. For this reason Richard has found it easier where feasible to have an employee based overseas; for example, in Spain and in Canada. These employees have the added advantage of knowing the area and being “socially embedded in that market.” Employees and language expertise is also of great importance for the documentation process involved.

Resource leveraging-through partnerships and alliances

Following one year of trading as GDS, in 2010 the company joined NMi. There were clear benefits of doing this for NMi, namely increased financial investment and greater cross-border opportunities. However, leveraging greater resources for the company in Wales also has managerial implications. Richard describes the managerial challenges when a small entrepreneurial fast-growth company joins an international group:

The timescales for decision-making become a much longer process. There are now levels of approval required in the parent companies. Also the agendas of the different international offices may differ. There need to be protocols for how we manage new competition and rules of engagement.

Entrepreneurial autonomy

NMi are autonomous to some degree and have to be profitable. Reacting to swift market changes means that Richard has had to make decisions ahead of the parent companies. This is not necessarily popular with the parent companies, but any time lapse can affect reaching for new opportunities, and so Richard and his co-founder sometimes take these calculated risks. As such these entrepreneurs in NMi are attempting to be the tail that “wags the dog”:

For example, Spain introduced a regulatory framework for online gaming in 2011 and invited testing companies to apply for approval at very short notice; we had to dive in and invest immediately without the usual internal agreement.

How does technology increase rules of engagement and develop new market opportunities?

Technology-driven companies work in fast-moving competitive, globalized markets. The speed of delivery of need technologies demands an increased speed of workload for companies and increased speed of decision-making. For example, with different time zones, email enquiries, and contacts via websites become a 24-hour concern. New markets open up quickly and response by the case study company has also to be quick in return to match the responses of their larger competitors. Some competitors deliver by cost reduction; for example, a much larger company based in India. NMi's focus on quality and efficiency has allowed them to become a major competitor in the market despite being small. Growth has been largely word-of-mouth and driven in two ways: the need to have approvals in multiple jurisdictions (in order to attract the bigger multinational customers); by current customers and their own intentions to move into new jurisdictions.

New jurisdictions introduce new requirements (these requirements are evolving worldwide to keep pace with new technological advances). NMi used to test new requirements like randomness and fairness, for example, change management, security testing (vulnerability scans, penetration testing—to assess IT systems for potential vulnerabilities and security exploits).

Human resource management and management of processes

As alluded to earlier in the chapter, swift internationalization requires new tools, processes, and language capabilities (for example, in Spain, test reports must be in perfect Spanish).

Therefore, the recruitment and selection of the right employees is important. In increasing the workload, computer systems need, even more than ever, to be automated. As NMi is automating all the time, specific job roles have to be created to carry out this objective, and so they constantly need software developers to work specifically on this. Hence, there is a need to ensure that processes and procedures within the company are embedded. Employee numbers have grown considerably and now, including “freelancers” abroad, NMi (Wales) employ 19 staff.

Proposal of a new model

The models described earlier in the chapter provide useful insights and would be valuable for inclusion in MBA or other similar programs focusing on IME. In fact, Figure 27.2, the growth stages model, identifies chasms whereby the entrepreneur is facing a crisis stage and where, if appropriately designed and delivered, degree courses could interject and offer support. As Richard acknowledges, often the modules were taught in a different order, and not designed for those thinking of starting a business. Of additional note is the fact that there are limited entrepreneurial models which include internationalization. Presumably the assumption is that a start-up business starts locally and establishes itself in familiar markets before reaching out into international markets. Although NMi started in the UK and culturally and linguistically in familiar markets, the use of technology, travel, and globalization of markets has meant that internationalization for SMEs can happen so much sooner, if not immediately, at firm inception.

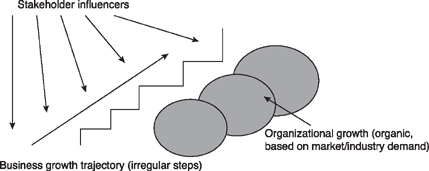

Figure 27.3 Internationalization firm growth model

Based on developing theories and on the NMi case study, a new model (Figure 27.3) is proposed that acknowledges the issues for new, entrepreneurial, high-growth technology internationalizing firms and makes the following set of assumptions:

• First, that firm growth that meets international business expectations requires radical step changes.

• Second, that internationalizing firms need to ensure protocols are in place to allow effective control of these changes (control of stakeholder groups/business relationships).

• Third, that the organizational structure needs to be continually adapted to meets the demands of the pervasive environment, on the basis that there is not one size that fits all.

Conclusion

This chapter has presented a very recent case study of a small, high-growth technology company. The thoughts and experiences of the entrepreneur in this business case, together with consolidation of business and SME strategy theory and models which are traditionally taught on business management programs, has allowed distillation of a new model (Figure 27.3), which, the authors of this chapter propose, provides a more realistic view of the demands of the entrepreneur in terms of managing the swift, organic growth of an early internationalizing firm. Managing and controlling stakeholders/business relationships is vital to new firm growth in new markets as is effectively managing and controlling the organizational structure of the firm throughout the radical step changes and phases of firm growth which take place. These findings consolidate the views of SME researchers whereby entrepreneurs overcome limitations of their business by providing an innovative product or service in new markets and by leveraging vital resources via use of networks (Carson et al., 1995; Hill, 2001).

This study demonstrates that IME is not only of significant relevance for those who wish to manage business which takes place in large organizations and in overseas markets but also for those entrepreneurs who wish to create successful new globalized ventures. Entrepreneurs need support to develop new competencies for controlling and managing growth-oriented ventures both in domestic and international markets. Often technical specialists in their respective industry fields, nascent entrepreneurs have an urgent requirement for developing business acumen and expertise at the point of start-up or prior to start-up. However, the evidence described here also points to the need for management programs such as MBA programs to offer flexible degree programs for entrepreneurs and also to ensure that IME is included within the curriculum. In order to do this, assumptions about entrepreneurial ventures have to change. In a globalized market environment the expectation of the entrepreneur is that new ventures can and do become “born global” or move into international markets in the early stages of firm growth. In the future, this needs to be reflected in the way governments and institutions provide IME support for our budding entrepreneurs.

Bibliography

Acs, J.Z. 1999. Are Small Firms Important? Their Role and Impact. Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Akgun, A.E., Lynn, G.S. and Byrne, J.C. 2004. Taking the guesswork out of new product development: how successful high-tech companies get that way. Journal of Business Strategy, 25(4): 41–46.

Analoui, F. and Karami, A. 2003. Strategic Management in Small and Medium Enterprises. London: Thompson Learning.

Bartels, C.P.A. and Wolff, J.W.A. 1993. Science Parken in Nederland [Science Parks in the Netherlands]. ESB article (November).

Berry, A.J., Sweeting, R. and Goto, J. 2006. The effect of business advisers on the performance of SMEs. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 13(1): 33–47.

Berry, M.M.J. 1996. Technical entrepreneurship, strategic awareness and corporate transformation in small high-tech firms. Technovation, 16(9): 487–498.

Beverland, M. and Lockshin, L. 2001. Organizational lifecycles in small New Zealand wineries. Journal of Small Business Management, 34(4): 354–362.

Bowman, C. 1998. Strategy in practice. London: Prentice Hall.

Business Innovation and Skills (BIS) (www.bis.gov.uk) (accessed May 20, 2012).

Carson, D., Cromie, S., McGowan, P. and Hill, J. 1995. Marketing and Entrepreneurship in SMEs — an Innovative Approach. Essex, UK: Prentice Hall.

Casson, M.C. 1982. The Entrepreneur: An Economic Theory. Oxford, UK: Edward Elgar.

Chaston, I. 1997. Small firm performance: assessing the interaction between entrepreneurial style and organizational structure. European Journal of Marketing, 31(11/12): 814–831.

Chaston, I. 2010. Entrepreneurial Management in Small Firms. London, UK: Sage.

Churchill, N.C. and Lewis, V.L. 1983. The five stages of small business growth. Harvard Business Review, 61(3): 30–50.

Collins, C. 1995. Cases in Strategic Management, 2nd edn. NewYork: Pitman Books.

Collinson, E. and Shaw, E. 2001. Entrepreneurial marketing — a historical perspective on development and practice. Management Decision, 39(9): 761–766.

Cooper, S.Y. and Park, J.S. 2008. The impact of ‘incubator’ organizations on opportunity recognition and technology innovation in new, entrepreneurial high-technology ventures. International Small Business Journal, 26(1): 27–56.

Devine, T.J. 1994. Characteristics of self-employed women in the United States. Monthly Labor Review, 117(3): 20–34.

Dunn, P. and Cheatham, L. 1993. Fundamentals of small business financial management for start-up, survival, growth, and changing economic circumstances. Managerial Finance, 19(8): 1–13

Enterprise Ireland (www.enterprise-ireland.com/en/fundings-supports/) (accessed March 20, 2012).

Eshima, Y. 2003. Impact of public policy on innovative SMEs in Japan. Journal of Small Business Management, 41(1): 85–93.

Fielden, S.L., Davidson, M.J. and Makin, P.J. 2000. Barriers encountered during micro and small business start-up in North-West England. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 7(4): 295–304.

Forum of Private Business. 2010. Research report referendum 191. Available at www.fpb.org/images/PDFs/referendum/Referendum%20191%20report.pdf (accessed March 20, 2012).

Gibb, A.A. 2000. SME policy, academic research and the growth of ignorance, mythical concepts, myths, assumptions, rituals and confusions. International Small Business Journal, 18(3): 13–35.

Gilmore, A., Carson, D. and Grant, K. 2001. SME marketing in practice. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 19(1): 6–11.

Greiner, L.E. 1998. Evolution and revolution as organizations grow. Harvard Business Review, 76(3): 55–60, 62–66, 68.

Griffin, R.W. and Pustay, M.W. 2005. International Business: A Managerial Perspective. Harlow, Essex: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Harris, R.I.D. 1988. Technological change and regional development in the UK: evidence from the SPRU database on innovations. Regional Studies, 22: 361–374.

Harrison, R., Mason, C. and Girling, P. 2004. Financial bootstrapping and venture development in the software industry. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 16(4): 307–333.

Hausman, A. 2005. Innovativeness among small businesses: theory and propositions for future research. Industrial Marketing Management, 34(8): 773–782.

Henderson, J. 2002. Building the rural economy with high-growth entrepreneurs. Economic Review, Kansas: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, 2002. Available at www.kansascityfed.com/PUBLICAT/EconRev/Pdf/3q02hend.pdf (accessed May 20, 2012).

Hendry, C., Brown, J. and Defillippi, R. 2000. Regional clustering of high technology-based firms: optoelectronics in three countries. Regional Studies, 34(2): 129–144.

Hill, J. 2001. A multidimensional study of the key determinants of effective SME marketing activity: Part 1 and 2. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 7(5/6): 171–235.

Hills, G.E., Hultman, C.M. and Miles, M.P. 2008. The evolution and development of entrepreneurial marketing. Journal of Small Business and Marketing, 46(1): 99–112.

Huggins, R. 1996. Innovation, technology support and networking in South Wales. European Planning Studies, 4(6): 757–768.

Johnson, G., Scholes, K. and Whittington, R. 2009. Fundamentals of Strategy. Essex, UK: Pearson Education.

Jones, R. and Parry, S. 2011. Business support for new technology-based firms: a study of entrepreneurs in North Wales. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 17(6): 645–662.

Jones, R. and Rowley, J. 2009. Marketing activities of companies in the educational software sector. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 12(3): 337–354.

Karami, A. 2007. Strategy Formulation in Entrepreneurial Firms. Aldershot, UK: Burlington, VT.

Keeble, D. and Kelly, T. 1988. The regional distribution of NTBFs in Britain, FSI/SQW, in New Technology-based Firms in Britain and Germany: An Assessment Based on a Project of the Anglo-German Foundation in Collaboration with Bundesministerium fur Forschungund Technologie and the Department of Trade and Innovation, 5, Fraunhofer-Institut fur Systemtechnik und Innovationforchung and Segal, Quince Wickstead: 209–213.

Laforet, S. and Tann, J. 2006. Innovative characteristics of small manufacturing firms. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 13(3): 363–380.

Luger, M.I. and Koo, J. 2005. Defining and tracking business start-ups. Small Business Economics, 24(1): 17–28.

Macke, D. and Kayne, J. 2001. Rural entrepreneurship: environmental scan. Kauffman Center for Entrepreneurial Leadership, Kansas City, Missouri, January 17.

Mohr, J. 2001. Marketing of High-technology Products and Innovations. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

O'Donnell, A. 2004. The nature of networking in small firms. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 7(3): 206–217.

O'Donnell, A., Gilmore, A., Carson, D. and Cummins, D. 2002. Competitive advantage in small to medium-sized enterprises. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 10(3): 205–223.

OECD. 1997. Government Venture Capital for Technology-based Firms. Paris, France: OECD Publishing.

Ojasalo J., Natti, S. and Olkkonen, R. 2008. Brand building in software SMEs: an empirical study. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 17(2): 92–107.

Perez, M.P. and Sanchez, A.M. 2003. The development of university spin-offs: early dynamics of technology transfer and networking. Technovation, 23(10): 823–831.

Ramsden, M. and Bennett, R.J. 2005. The benefits of external support to SMEs: “Hard” versus “soft” outcomes and satisfaction levels. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 12(2): 227–243.

Reid, G.C. and Smith, J.A. 2000. What makes a new business start-up successful? Small Business Economics, 14(3): 165–182.

Rothwell, R. and Dodgson, M. 1992. European technology policy evolution convergence towards SMEs and regional technology transfer. Technovation, 12(4): 223–238.

Sandler-Smith, E., Hampson, Y., Chaston, I. and Badger, B. 2003. Managerial behavior, entrepreneurial style and small firm performance. Journal of Small Business Management, 42(1): 47–67.

Schindehutte, M., Morris, M. and Pitt, L. 2009. Rethinking Marketing — The Entrepreneurial Imperative. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Simpson, M. and Taylor, N. 2002. The role and relevance of marketing in SMEs: towards a new model. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 9(4): 370–382.

Steffensen, M., Rogers, E.M. and Speakman, K. 2000. Spin-offs from research centers at a research university. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(2): 93–111.

Storey, D. J. and Tether, B.S. 1998. Public policy measures to support new technology-based firms in the European Union. Research Policy, 26: 1037–1057.

Technology Strategy Board. www.innovateuk.org (accessed May 20, 2012).

Tersvioski, M. 2003. The relationship between networking practices and business excellence: a study of small to medium enterprises (SMEs). Measuring Business Excellence, 7(2): 78–92.

United States General Accounting Office (USGAO) 1998. Federal Research: Interim Report on the Small Business Innovation Research Program. Washington, DC: US, GAO.

Van Geenhuizen, M. 2008. Knowledge networks of young innovators in the urban economy: biotechnology as a case study. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 20(2): 161–183.

Van Tilburg, J.J. and Vorstman, C.M. 1994. Ordernemen met technology (Entrepreneurship with Technology). Enschede, March.

Welsh Assembly Government Business and Economy. 2010. Available at: http://wales.gov.uk/topics/businessandeconomy/?lang=en (accessed May 20, 2012).

Westhead, P. and Storey, D.J. 1994. An Assessment of Firms Located On and Off Science Parks in the United Kingdom. London: HMSO.

Whittington, R. 1993. What is Strategy and Does it Matter?. London: Routledge.