MANY social psychologists and sociologists are severe critics of the classical approach. They point out that it is people who are organized, yet the classical approach does not take into account people's likely behaviour under different organizational arrangements. It concentrates on their physical capacities and needs and ignores the emotional aspects of human nature. Members of an organization are viewed as passive instruments, content to act only in accordance with the rules laid down, whereas, in fact, they may pursue activities of their own which do not conform to official policy. Work groups, for example, develop their own social structure. Unless steps are taken to enlist their co-operation as an informal group, they may adopt values and practices that seriously limit the company's ability to attain its ends.

Much of the criticism is of recent origin, dating from about 1950. Before this time, research by social psychologists and sociologists was regarded as supplementary to the classical approach; conflicts tended to be ignored. Weber, a German sociologist writing at the beginning of the century, said that the most rational means for attaining an organization's prescribed goals was a ‘bureaucracy’. By this he meant the large-scale organization run by specialists and professional managers emphasizing rules, records and regulations to guide conduct and decision making. Weber's ideas were developed independently and his theory of bureaucracy was part of a general theory of social and economic organization.56 Elton Mayo's work, which initiated the human relations approach, was widely publicized by classical writers. The lack of conflict between the protagonists of human relations such as Mayo, and classical writers, exemplified by Urwick, is well illustrated by the following quotation. It is taken from Mayo's foreword to Urwick and Brech's book on the Hawthorne investigations.

‘Lyndall Urwick was the first person to take public notice of the successive studies of human relations in industry undertaken by the Western Electric Company.... I hope that the book will be read widely by the many who are, in these days of difficulty, vitally interested in the human problems of modern industry.’57

There is no doubt that the classical approach is an inadequate statement of the factors to be considered in organization. The way people behave cannot be ignored any more than the behaviour of materials can be ignored when building a house. Ignoring behaviour in either case can result in failure or the revision of plans; economy of effort demands that all factors relevant to organization should be considered together.

The human relations approach is an attempt to define a social environment that stimulates people to strive for overall objectives. Hence it tries to create an organisation which

(i) achieves objectives while satisfying its members (if organization creates dissatisfaction among the bulk of its members, it is not in a state of equilibrium),

(ii) encourages high productivity and low absenteeism,

(iii) stimulates co-operation and avoids industrial strife; it is not suggested that all minor conflicts and disagreements are to be avoided. Some disagreements (‘constructive’ conflicts) are inevitable and healthy; the aim is to avoid creating situations where people constantly work against each other (‘destructive’ conflicts).

In this approach the study of organization becomes wholly the study of behaviour; of how people behave and why they do so. Its exponents hope to predict behaviour within different organizations and to provide guidance on how best to achieve the organizational arrangements that evoke co-operation. More specifically, the approach has been concerned with the effect of organization on:

(i) individual and group productivity,

(ii) individual development,

(iii) job satisfaction.

The study of behaviour within the business organization can be conveniently divided into:

1. Individual needs and wants.

2. Behaviour of small work groups.

3. Behaviour of supervisors.

4. Inter-group behaviour.

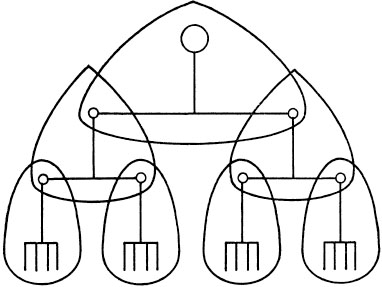

FIG. 16.—The stimulation of needs and wants leads to behaviour directed towards goals which are likely to satisfy the need or want.

The pattern of individual behaviour is illustrated in Fig. 16. Each person has certain needs and wants. When stimulated, they give rise to behaviour directed towards goals which are perceived as likely to satisfy. If people's wants and needs (i.e. their motives) were limited in number and could be identified and measured for relative importance, it might be possible to design an organization in which the employee best satisfied his needs and wants by contributing to the overall goals of the organization.

Needs and wants can only be identified indirectly. To do so requires observation of behaviour and collection of opinions. Since it is difficult to structure a situation or a questionnaire in a way that avoids all ambiguity in interpreting underlying motive, no classification of wants and needs has so far received universal acceptance. How is a strong demand for higher wages to be interpreted? Is it an attempt to satisfy the longing for security or the drive for higher social status or ... ? We could go on indefinitely. Many motives arise purely through people's contact with the world around them and would not arise without such contact. In an atmosphere of ‘keeping up with the Joneses’, for example, motives are apt to change as the environment changes.

There is some agreement, however, that motives can be classified into physiological needs and psychological wants. Physiological needs such as hunger, thirst and sex are common to all and develop in everyone regardless of the social environment. Psychological wants, however, appear infinite in number and there is difficulty in demonstrating any wants that are common to man in general. Psychologists speculate as to how they develop. Some develop because they are associated with the satisfaction of the physiological needs. A baby cries to be picked up because this is associated with being fed. In whatever way wants are acquired, they can become the basis for learning other wants, so it becomes impossible to account fully for those found in adults.

If it is difficult to identify and classify wants and needs, it is even more difficult to measure their relative strengths. However, Maier,58 Argyris59 and McGregor60 have ranked them as follows: physical, safety, social, egoistic and self-actualization. It is argued that people seek to satisfy their needs in this order of priority. As the more pressing needs are satisfied, people become concerned with self-actualization, i.e. concerned with realizing their full potential. It follows that, in times of prosperity, an organization which encourages narrow specialization and emphasizes close control may prevent people from achieving satisfaction at work, hence frustration may result. Argyris objects to such notions as task specialization, chain of command, span of control, on the ground that emphasis on these factors in an organization is inconsistent with the needs and characteristics of the normal adult.

Although the above classification and ranking of needs and wants has considerable intuitive appeal, it is still largely speculative: measuring the relative importance of wants and needs raises problems which have not yet been solved.

Frustration

The supporters of the human relations approach claim that many organizational arrangements give rise to frustration. The term therefore needs to be explained. Frustration arises:

(i) where there is a barrier to achieving some strongly-desired goal; it may be that the formal organization causes frustration if it is a barrier to self-actualization;

(ii) where two wants compete with each other for satisfaction, though many such conflicts are of no significance, simply giving rise to momentary indecision.

Psychologists have classified the various types of frustration.

(i) ‘Running into a stone wall.’ Frustration arises if some obstacle lies in the way of achieving some highly desired goal.

(ii) ‘The donkey between two bales of hay’ describes the situation where a choice has to be made between equally attractive alternatives. Though this situation can lead to indecision, it is seldom frustrating since no deep anxieties are roused.

(iii) ‘The devil and the deep blue sea.’ In a situation where alternatives are equally distasteful, the first impulse is to run away. On this basis it is not surprising, if work is distasteful, that there should be high absenteeism and high labour turnover. The employee both hates his job and fears the consequences of not doing it.

(iv) ‘Have his cake and eat it.’ A worker may want more money but prefers to restrict output rather than incur the displeasure of his colleagues.

Psychologists are also concerned with classifying reactions to frustration in order that frustration may be predicted from behaviour. However, there is still no generally agreed classification though the most common reactions mentioned are aggression, rationalization, resignation, regression and sublimation.

(i) Aggression. The most common reaction to frustration is aggression. We hit back when frustrated though we may choose to use a scapegoat. We may even blame and hate ourselves. Industrial history is full of examples of aggressive behaviour which may be due to frustration. The Luddites are perhaps the most familiar. In fact, the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1871, though repealed in 1875, was specifically directed against ‘Acts of violence, intimidation, molestation and obstruction’ by trade unionists.

(ii) Rationalization is the ‘sour grapes’ reaction to frustration. For example, employees whose performance is assessed on subjective factors, such as managerial attitude, may rationalize their low assessment as merely a reflection of prejudice on the part of those making the judgment.

(iii) Resignation arises if some frustrating situation is apathetically accepted. It reflects itself in a ‘couldn't care less’ attitude.

(iv) Regression. People may ‘regress’ or behave childishly in conditions of frustration, as in childish emotional outbursts and name calling from otherwise mature adults.

(v) Sublimation is an adaptive reaction, whereas the other reactions discussed are non-adaptive. In sublimation, frustration is removed by a transference of concentration to other goals, usually at a higher aesthetic or abstract level. Since managers cannot remove all frustration at work, they may try to get people to remove their conflicts by getting them to concentrate on other goals or by changing their minds about the importance of some of their wants.

People within a business organization do not generally behave as isolated individuals. They are either formally organized into groups or come together voluntarily and, in consequence, influence each other's behaviour. We often speak of companions having a bad or good influence. This is an overt recognition that attitudes, wants and behaviour are influenced by association with others.

The behaviour of work groups is important at every level in the organization. The human relations school claims that, in general, the behaviour of workers, supervisors and managers can be best understood and predicted through analysing the relationship among those who share some common group membership at work.

A ‘group’ exists when people associate with each other for some purpose. Without such a sense of common purpose and interest as a link, no group exists. Hence, the middle classes do not normally form a group unless their interests are threatened. On the other hand, a trade union is a group because its members believe that they have purposes and interests in common. The main emphasis, however, lies not in secondary groups such as trade unions but in primary groups or groups whose members have more direct contact with each other. Primary groups in practice shade off imperceptibly into secondary groups.

The early study of behaviour within work groups was carried out at the Hawthorne (Chicago) Works of the Western Electric Company in the USA in the 1920's and early 1930's. The study was initially concerned with the effects on worker productivity of such physical factors as illumination, temperature and work schedules, but social factors, within the broad limits considered, proved more important than physical environmental factors. For example, the output of inspectors, coil winders and relay assemblers was measured under different lighting conditions. The output of the inspectors varied, but not in relation to the level of illumination. However, output from the coil winders and the relay assemblers did increase as the level of illumination was raised, but did not decrease when the level of illumination was subsequently lowered. In fact, a further study showed that merely changing the light bulbs without changing the light intensity increased output. The investigators had stumbled on to the importance of social factors in human motivation instead of discovering the relationship between physical factors and worker performance; the company had shown an interest in employee welfare and work people had responded. Social psychologists now refer to the ‘Hawthorne’ effect to cover those cases where the effect of direct observation in itself improves the performance of those being observed.

In order to achieve greater control, the Hawthorne investigators separated, from their regular department, a small group of workers employed in assembling telephone relays. The group was established by asking two friends to choose three other friends, The social situation fostered friendly relations among the workers and strict supervisory control was abandoned. The conditions of work, such as length of rest pauses and method of payment, were varied systematically, but productivity increased regardless of these changes. There was a possibility that the increase in output was related to changes in the financial incentive scheme. The group was being paid on its own performance whereas previously its members had been paid on the output of the whole shop consisting of a hundred operators. Two further experiments were, as a consequence, carried out to check whether it was the long-term effect of the financial incentive scheme which lay behind the increase in output. In the first experiment a second relay assembly group, again consisting of five girls, was brought together. Unlike the first assembly group, they remained in the regular shop but they were still paid in the same way, that is, on the output from their group alone. In the second of the two experiments, a third group—a mica-splitting group—was formed. This group were put into a separate room in conditions resembling those given to the first relay assembly group except that they were paid not on their own output but on the output of the shop as a whole. During the experiments the second relay assembly group increased output by 12 per cent and the mica-splitting group increased output by 15 per cent. However, since the original assembly group had increased output by 30 per cent it was argued that the original increase could not be attributed to the financial incentive alone. In fact, Roethlisberger of Harvard and Dickson of the Western Electric Company61 are reluctant to attribute any credit for the increase in output to the financial incentive, because a number of social factors were introduced unwittingly into the experiments. The change in the wage incentive was not, therefore, the only factor that was varied. The psychologist, Viteles, makes the following comment.

‘In particular, the experiments do not demonstrate that rest pauses and wages are without value as incentives to production. Furthermore, they do not justify the firm conclusion that these (or other conditions) fail to exercise independent effects upon the individual. Nevertheless, the experiments served an important purpose in calling attention to the fact that interpersonal relations and the character of the social situation can alter the effects of such specific incentives.’62

‘Social considerations, according to the Hawthorne investigators, also outweigh economic ones in determining workers’ feelings and attitudes, and thereby in determining the nature of individual satisfactions and grievances in the working situation. Objections can be raised to these generalizations, particularly to the implication that financial incentives cannot have a direct and independent influence upon output. As suggested earlier, data from the Hawthorne studies which are interpreted as revealing the effect of group sentiments can be interpreted as showing the immediate and definite influence of a change in the wage plan. Certainly, the findings of the Hawthorne studies cannot be accepted, as has apparently been done in some quarters, as demonstrating that the worker is not concerned with the size of his pay envelope except as an outer symbol of the social value of his job, and that he will ordinarily not respond directly with increased effort to an enhancement of the financial incentive.’63

A further important study carried out at the Hawthorne plant involved a group of fourteen experienced male operators wiring banks of relays. This group was placed in a separate room to facilitate observation. Nine of the fourteen operators wired electrical connections, three of them soldered the connections and two of them inspected the finished connections. A team was composed of three wiremen and one solderman. The group followed certain uniform patterns of behaviour which did not follow the official set-up. It restricted output in spite of the presence of a financial incentive, and rules and standards set by the Company were often replaced by those set by the group, and it was group standards (or norms) which members followed. Social factors within the group were the deciding factor in worker output and an informal organization existed; that is to say informal relations developed among workers which gave rise to organized patterns of conduct within the group. Group standards were enforced by ridicule and, if necessary, by hard blows. For example, anyone who worked too hard was a ‘rate buster’ or a ‘speed king.’ Anyone whose output was below group standard was a ‘chiseler.’ The group was divided into two separate cliques, though the two cliques were united in enforcing common norms. Within each clique there were differences in status. The wiremen occupied a higher status than the soldermen even though their pay was the same. The group had thus an intricate informal social structure or organization which had arisen without the intervention of management.

A good deal of work has been done subsequently on the behaviour of work groups. Any work group is more than the sum of its parts because members conform to certain standards of behaviour approved by the group. When a number of people form a group, customs develop which are regarded as an aid to the purpose at hand. No new member can associate with the group for long without adjusting his behaviour to fit. Some group standards, customs or norms, are formally accepted as rules but many remain unwritten. There are many things ‘just not done’ in a club which do not find expression in the rules of the club. Group members are obliged to conform to these evolved patterns of behaviour if they are to be accepted; they fall in line or get out. In practice, group customs are accepted by new members because they want to conform and so be accepted. Every act of each new member is strengthened or weakened (reinforced positively or negatively) depending on the extent to which other group members indicate approval or disapproval.

Arthur Koestler described in The Observer (February 10, 1963) his initiation into the ways of a work group:

‘I learned to conform to our unwritten Rules of Life: Go slow; it's a mug's game anyway; if you play it, you are letting your mates down; if you seek betterment, promotion, you are breaking ranks and will be sent to Coventry. My comrades could be lively and full of bounce; at the working site they moved like figures in a slow-motion film, or deep-sea divers on the ocean bed.

‘The most cherished rituals of our tribal life were the tea-and-bun-breaks—serene, protracted, like a Japanese tea ceremony. Another fascinating tribal custom was the punctuation of every sentence with four letter-words used, as adjectives, without reference to meaning, compulsive like hiccoughs. It was not swearing, these strings of dehydrated obscenity served as a kind of negative status symbol.’

Violence can be still used to ensure conformity: ‘A guardsman yesterday told officers of an alleged two hour “punch-up” he received for letting the side down by going to bed with a dirty face.’

Even a strong and dominant personality must conform to some extent and gauge how far he can go at any one time in modifying the accepted codes of behaviour. Work groups usually develop norms on such matters as what constitutes a fair day's pay and other working conditions. It is foolish to ignore such norms or to dismiss them as mere prejudice. It is common sense to try to get work groups to go along with change through understanding their perceptions rather than giving them the impression of being pushed around. As one writer says, ‘Much pegging of output at a certain level by employees is an expression of this need to protect their ways of life as well as their livelihood from too rapid change.’

As an example of the way a work group can vitiate management plans, is the case described by Selekman. Five workers in a clothing plant were required by management to sew only one section each of a coat whereas previously they had worked as a team and completed sewing the five sections together. The aim by management in making the change was to put each man on individual bonus. However, the five men, though of different abilities, continued to share the bonus.64

Are work group norms ever conducive to the achievement of management goals? Fortunately, a work group may identify its interests with those who formed it so that informal and formal goals coincide. What if goals do not coincide? Can psychologists suggest some means for reconciling the two? The main method so far developed is to involve work groups in decisions that directly affect them. This will be discussed later.

THE ‘MAJORITY’ EFFECT

The tendency to conform to group pressures is stronger than most people suspect. Group members are prepared on occasions to see black as white if their colleagues argue that way. One psychologist, Asch, devised an experiment in which subjects were invited to match the length of a given line with one of three unequal lines. The task was easy and participants left alone found it so. However, when a subject found himself in the company of others who, like himself, had to voice their opinions aloud, but had also been instructed to agree on a judgment which was clearly wrong, there was a strong tendency for the odd man out to fall in line with the majority opinion. This ‘majority effect’ is even more marked in circumstances where the discrimination is difficult though a subject is less likely to conform if he has supporters.65

A business, like a group, can demand a high degree of conformity and loyalty from its executives with undesirable side-effects on individual creativity, as pointed out by W. H. Whyte in his famous book The Organisation Man.66 The community, too, can make demands. Riesman suggests that in American suburbia there is high pressure on a child to behave as other children, and this comes not only from other children but also from parents and teachers. Parents worry if a child is the odd one out even if his behaviour is in no way criminal. He claims that in America there is an admiration for the man who can influence people, but scepticism towards accepted belief is not encouraged. As a consequence, creativity is not encouraged as this presupposes uneasiness about the existing state of affairs.67

PROBLEM SOLVING IN GROUPS

In spite of what has been said, two heads are often better than one. Where the solution to a problem is a matter of logic or knowledge, then a large group is likely to contain some expert whose confidence wins over the rest. In fact, even the views of the expert might be improved by the opinions of the laymen. There have been a number of experiments in which people in groups give a collective solution which is better than any individual solution. Most problems, however, considered in these experiments led to solutions which did not conflict with group aims. If a possible solution to a problem does, in practice, conflict with certain group attitudes, an individual may be inhibited and hesitate to make his colleagues face realities.

LEADERSHIP IN GROUPS

If a person exercises influence over colleagues much more than they do over him, he is said to exercise leadership. If this influence covers a wide range, he is described as a leader. It is commonplace to view a leader as possessing a combination of personality traits so that we speak of choosing ‘natural leaders’ and attempt to list their supposed qualities. The position in practice is more complex. Whether leadership is provided to a group depends not only on personal characteristics but on the situation in which the group finds itself. The communist who is normally ridiculed may be the chosen leader during a strike if there is a feeling that he will not compromise in negotiation. Hence, leaders in one situation may be unacceptable in another. The positions of Chamberlain in 1939 and Churchill in 1945 will readily come to mind.

The work group leader is likely to be the person whose activities most coincide with group norms, that is, the man whose behaviour is perceived as most likely to achieve group needs. This concept of leadership has serious implications. The leader cannot deviate too quickly from the expected pattern of behaviour, though, if he rates high in carrying out the main rules, his infringement of minor ones may be overlooked. An attempt to win over the leader, even if successful, does not ensure winning over the group. Social psychologists emphasize that managements are not dealing with a ‘rabble’ but with ‘well-knit work groups’. Hence, it may be more effective to deal with a small group as a whole than to deal separately with individual group members. Groups can be persuaded to change together, whereas the single member may close his mind to argument if a change in his behaviour implies facing group disapproval.

ATTITUDES AND MORALE

Wants and needs, when aroused, influence behaviour. However, the particular want or need aroused results not so much from the stimulus itself as from the way the stimulus is experienced. The manager and worker may experience the same situation in different ways. A new machine may be regarded by the manager simply as a means for reducing costs, while the worker may regard it as a threat to his economic security and react accordingly.

The way in which a stimulus is experienced depends on attitudes which are usually developed through group membership, as groups tend to control attitudes by the same mechanism as they enforce other norms. In practice both attitudes and motives interact upon each other. An attitude is usually defined as a state of readiness to respond in a certain way to a particular type of situation. From the thousands of different ways of responding to various situations, there are some uniformities or acquired predispositions to react in certain ways to some particular object, situation or person. These predispositions are based on the attitudes held. From a knowledge of attitudes it may be possible to predict opinions or reactions to some point at issue; conversely, attitudes are gauged by examining opinions and reactions. If we know that a group has a suspicious attitude to management, it would not be hard to predict its likely reaction to the suggested introduction of work measurement. Attitudes so strong as to make the individual ignore the evidence are called prejudices. People are not always aware of their prejudices; this was indicated by an experiment in which students ranked sixteen pieces of prose in order of merit. The passages had all been written by Stevenson but were attributed to a variety of authors whom the students had already ranked in order of merit. The ranking of authors and the rankings of the pieces of prose attributed to them were highly correlated.68

Management is obviously interested in creating ‘right attitudes’ to facilitate changes of behaviour. Since the normal communication between worker and management gives too crude a measure of existing attitudes, there has been a growth of more direct means of measurement. Unfortunately, much social psychology today is concerned with collecting information about attitudes; consequently, fundamental work on organizational behaviour (such as the Hawthorne experiment) is rare.

The crudest measure of attitude would be simply to count up the number of people for or against some particular view. This, however, would merely measure the direction of attitude whereas for deeper understanding it is also necessary to measure both the extremeness of the attitude and the intensity of feeling involved. Sometimes the salience of the attitude is also measured, i.e. whether the attitude occupies a major or minor position in the total scale of attitudes held. The attitude towards war is likely to have a higher ranking relative to other attitudes than it did before World War II.

There are a number of ways of evolving an attitude scale in order to describe and rank people's attitudes. By one method, after the particular attitude has been defined (for example attitude towards payment by results) several hundred statements on the subject are collected. A large number of judges (50 to 300) working independently rank these statements into eleven groups, ranging from an extremely unfavourable attitude to an extremely favourable attitude towards the subject. The sixth position is regarded as neutral, reflecting neither favourableness nor unfavourableness. Those statements giving rise to ambiguity in ranking are discarded.

The remaining statements are given a scale value ranging from (say) zero to ten. A final selection is made from the statements to cover the scale from one extreme position to the other.

Example

Scale Value |

|

10 |

1. I think this company treats its employees better than another company. |

8.5 |

2. If I were starting again I would still join this company. |

|

etc. |

Note: Scale values not shown on questionnaire. |

|

The employee marks all statements with which he agrees and his ‘attitude score’ on the subject is the average of all score values he has marked. It should be noted that, since attitude is an ‘intensive’ quality like ‘softness’, it is meaningless to say that one man's attitude is 50 per cent higher than another man's if he obtains a score of nine as against six. Also, identical scores by this method of measurement may reflect different attitudinal patterns since identical average scores can arise from marking off radically different statements.

The measurement of morale is similar to the measurement of attitudes, morale being one reflection of attitudes. Although morale can be defined in terms of job satisfaction, there is growing agreement that the term be reserved to cover team spirit. On this definition, it is possible for each member of a work group to be highly motivated but for morale, or team spirit, to be low. High morale can sometimes work against the formal organization; high morale in some prisoner-of-war camps did not help the guards. Similarly, morale may be high during a strike. Where group purposes and organization objectives are made to coincide, high morale, by fostering a cooperative spirit, helps to achieve an integrated effort. The fact that industrial situations today frequently demand close cooperation is a further reason in favour of stimulating morale.

The measurement of attitudes and morale is still crude. What people say they do and what they actually do are often very different, and yet attitude measurement attempts to measure people's predisposition to act in a certain way. Even when questionnaires are unambiguous, contain no leading questions or emotive language and the sampling of items on the questionnaire is adequate, there is still the problem of whether people give truthful replies. No amount of statistical juggling can eliminate the factor of dishonest replies and the unconscious bias of interviewers. There is only one way of writing ‘no’, but many ways of saying it. Viteles illustrates this possibility of bias by quoting an investigation by Rice into the recorded interviews made by twelve trained and conscientious interviewers among 2,000 homeless. Rice found that one interviewer who was an ardent prohibitionist had attributed the downfall of 62 per cent of those interviewed to alcohol and 7 per cent due to industrial conditions. A socialist interviewer found alcohol was the reason in only 22 per cent of cases and 39 had been the result of industrial conditions; whilst the prohibitionist stated that 34 per cent of the homeless had themselves given alcohol as the cause of their downfall, the socialist quoted only 11 per cent as giving alcohol as the reason.69

Obviously, tests of the reliability and validity of each attitude survey are essential if they are to be used to predict behaviour rather than to describe collective opinion. A test of reliability is concerned with the consistency of answers. When groups are tested and then re-tested the degree of correlation between answers indicates reliability, that is, reliability means that comparable but independent measures of the same attitude should give similar results. Tests on validity are concerned with ensuring that differences in scores reflect true differences among individuals in the characteristics being measured so that the survey measures what it sets out to measure, i.e. a predisposition to react in a particular way to a given situation. Some tests of validity have been merely concerned with ensuring consistency in interpreting the underlying attitude behind answers given. This is insufficient. The findings of an attitude survey should be used to predict and its validity should be established by demonstrating that the predictions are adequate. This is the counsel of perfection as there are many practical difficulties involved. One is the same as that encountered in the measurement of motives.

People may not attempt to satisfy one deep want because it is incompatible with satisfying some even deeper want. Where there is a multiplicity of wants, the satisfaction of one may mean not satisfying others. In the Hawthorne experiment, individuals in the bank wiring group preferred to stay true to group norms than to earn more money by increasing output. Hence, a survey may detect an attitude, but that attitude may not reflect itself in behaviour because other factors in the situation may inhibit it. Some attitudes, as a consequence, may never get beyond stated opinion.

There are a number of more indirect ways of determining attitudes than those discussed. All, however, are difficult to test for validity. As Selltiz, Jahoda, Deutsch and Cook point out:

‘As we indicated earlier, many questions have been raised about the validity of indirect techniques, and relatively little research evidence is available to answer them. Actually, as noted in the preceding chapter, there is not much evidence of the validity of direct techniques depending on self-report, such as interviews and questionnaires. The validity of such instruments is less often questioned, however, probably because of the ‘obvious’ relevance of the questions to the characteristics they are intended to measure. It is the degree of inference involved in indirect tests—the gap between the subject's response and the characteristic it is presumed to indicate—that intensifies questions about validity.’70

MEASURING GROUP DIMENSIONS

Questionnaires have been designed to compare and describe the internal relations of work groups as a basis for predicting behaviour. For example, they have been designed to describe groups along the following dimensions:

Intimacy: Degree to which members are acquainted with each other.

Homogeneity: Degree to which members resemble each other in background of age, sex, attitudes.

Hedonic Tone: Degree to which members find pleasure in membership of group.

Autonomy: Degree to which group is independent of other groups.

Control: Degree to which group regulates behaviour of members.

Flexibility: Degree to which procedures are laid down.

Stratification: Degree to which members’ status is defined.

Permeability: Degree or ease to which new members are admitted.

Polarisation: Degree to which members are orientated towards specific goals.

Cohesiveness: Degree to which means of achieving goals are shared or the extent to which the group functions as a unit.71

For example, a group high in morale would be high in cohesiveness, participation and stability.

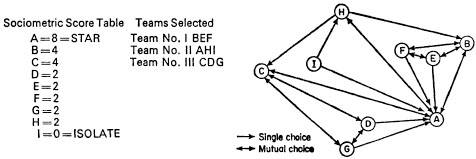

Another technique used to describe the internal relationships of groups is the sociogram. Each member of a group indicates his acceptance or rejection of other members according to some given clear-cut criterion. Where a questionnaire is used, care has to be taken to make sure the criterion is unambiguous.

In an office reorganization (by the author) nine clerks were formed into three teams of three to achieve a better manning on sections and to ensure that at least one clerk in each team was available to answer telephoned queries from customers. Each clerk was asked to choose three others with whom he would like to work. The resulting sociogram is shown in Fig. 17. ‘A’ is called a ‘star’ and ‘I’ an ‘isolate’. In fact, ‘I’, in spite of specific instructions to nominate three others, only chose two. From this sociogram each member's sociometric score can be calculated by adding up the number of occasions he was chosen.

FIG. 17.—Sociogram showing the preferences when members were asked to nominate three other group members with whom they would like to work. ‘A’ is the informal group leader.

The sociogram was used to choose the three teams and these are also shown in Fig. 17. The presence of star ‘A’ in team AHI raised its prestige from what would otherwise have been a very low level. ‘A’ also, in growing closer to ‘H’ and ‘I’, had the effect of getting them integrated with the rest of the group. The sociogram shows the high position of influence held by ‘A’, which is a factor making for group cohesiveness in spite of the closeness of clique BEF.

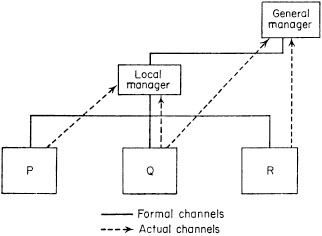

In the same case, three supervisors P, Q, R, were asked to say with which superior they had most business contact. The dotted line in Fig. 18 indicates their answers. R claimed he had most dealings with the general manager to whom his own superior reported, while Q insisted he had equal dealings both with his own superior and the general manager. It transpired that the relations between the local and the general manager were strained and Fig. 18 reflects the by-passing of the local manager by the general manager.

FIG. 18.—Sociogram showing the formal and informal communications net between supervisors and managers.

The supervisor may be described as the interlocking pin that links together the formal organization and the work group. The human relations school regards the attitudes and behaviour of the supervisor as a major factor in influencing work group behaviour; more specifically, as a major factor in determining group productivity and job satisfaction. All the recommendations as to ‘ideal’ supervisory behaviour lead to what has been called ‘power equalization’, that is, to reducing the differences in power and status between supervisor and subordinate.

How should the supervisor behave, or in fact how should any superior behave, to those beneath him if he is to achieve high productivity? Remember that leadership is not now evaluated purely in terms of a stereotyped list of personality traits but in terms of the behaviour that is effective in influencing others in the given situation. There are, of course, innumerable specific behaviours exhibited by supervisors but these can be classified into a limited number of groups, the behaviours within each group being identical from the point of view of their effect on subordinates. Although there is no one supervisory pattern of behaviour which under all circumstances is most effective, it is claimed that employee-centred rather than job-centred, democratic rather than authoritative supervisory behaviour, is more likely to achieve high productivity and job satisfaction.

EMPLOYEE-CENTRED VERSUS JOB-CENTRED SUPERVISION

Rensis Likert of Michigan University distinguishes between employee-centred and job-centred supervision.72 The employee-centred supervisor:

(i) Is considerate but firm and acts in a way that emphasises personal worth. He has a genuine interest in the success and well-being of subordinates.

(ii) Does not interfere but is supportive.

(iii) Has confidence in his subordinates and therefore his expectations are high. He sets high goals but leaves his subordinates to get on with the job.

(iv) Develops high group loyalty and uses participative techniques.

The job-centred supervisor channels his attention on the job to be done and is apt to regard employees merely as instruments for achieving production goals. He gives close supervision and delegates as few decisions as possible.

Likert argues that, in general, employee-centred supervisors achieve the higher productivity. A supervisor will not give leadership to his work group unless he helps them to achieve their goals, which postulates his being employee-centred.

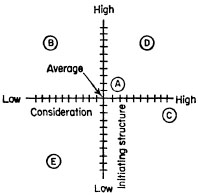

FIG. 19.—Consideration and Initiating Structure as co-ordinate, independent axes. Supervisor A is about average on both dimensions. Supervisor D is high on Consideration and Structure behaviour. Supervisor C is high on Consideration and average on Structure. Supervisor B has a pattern which many would call ‘authoritarian’. Supervisor E appears to operate in a laissez-faire manner and may not be exerting much ‘leadership’. A particular supervisor's relative standing on these dimensions may be measured by means of a questionnaire. (Reprinted by permission from Gagné and Fleishman, Psychology and Human Performance, copyright (c) 1959 by Holt, Rinehart & Winston, Inc., New York.)

A similar conclusion to Likert's is taken by Fleishman, who claims that the ideal supervisory behaviour from the point of view of getting the best out of subordinates is that which emphasizes consideration and also gives a firm lead.73 Fig. 19 illustrates the position. Supervisory behaviour should be positive in both consideration and initiating structure (giving a definite lead) though the exact position will vary with the situation.

Consideration

(i) He sees that a person is rewarded for a job well done,

(ii) He makes people feel at ease when with him,

(iii) He backs his men,

(iv) He discusses proposed changes with his subordinates if the changes affect them,

and so on.

Giving a firm lead

(i) He criticises bad work,

(ii) he encourages people to make greater efforts,

(iii) he offers new approaches to problems,

and so on.

The essential point to note is that the two patterns of behaviour are independent of each other. Contrary to popular belief, it is possible to be considerate and at the same time to give positive direction to subordinates.

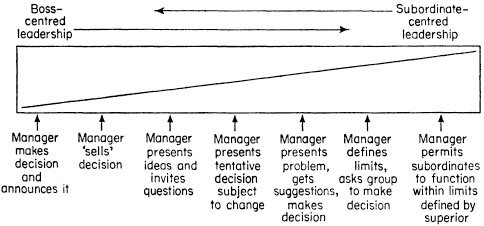

PARTICIPATION

The two extremes in behaviour are autocratic (treat ’em rough and tell ’em nothing) ranging through to laissez-faire, where people are allowed to do as they like. The most efficient supervisory behaviour lies somewhere between these two extremes: people do not like a tyrant, but neither do they like someone who is too lax. In Fig. 19 supervisor A is about average on both measures; B can be described as authoritarian; C is high in consideration and average on structure; D is high on both consideration and structure, while E can be described laissez-faire. There appears to be general agreement that the laissez-faire pattern gets less out of subordinates than any other supervisory behaviour.

FIG. 20.—Continuum of leadership behaviour, (from Leadership Organization by Tannenbaum, Weschler and Massarik, copyright© 1961, used by permission of McGraw-Hill Book Company).

Fig. 20, showing a range in supervisory behaviour from authoritarian to extremely democratic, indicates that the essential difference between the two ends of the range lies in the degree of authority used by the superior and the amount of freedom in decision-making given to subordinates. Under democratic leadership, subordinates participate in decisions that affect them but are not allowed to do just what they like as under laissez-faire leadership. It is claimed that democratic leadership is more effective in getting high performance because it achieves personal commitment to decisions made collectively, and encourages individual creativity. Furthermore, where work groups participate, then group pressure brings about overall commitment of the group. Where several levels are involved, it is preferable to give the lowest levels an early opportunity to participate if participation is not to appear illusory.

In general, the human relations school is concerned with achieving work group participation in the decision-making process. Full work group participation might be carried out as follows:

Assume ‘A’ wishes to get work group ‘Z’ to accept (say) work measurement. Group ‘Z’ are called together and perceive through discussion the management problem in work scheduling, etc. Also through discussion, work group ‘Z’ takes on the task of considering a solution. Various suggestions are made by ‘Z’ and ‘A’ points out their drawbacks, if any. Work measurement is suggested (perhaps by ‘A’) and considered, or a possible solution may be suggested by ‘Z’ that is acceptable to ‘A’. If work measurement is unacceptable to ‘Z’ and any other solution unacceptable to ‘A’, then the matter is postponed since a solution must not be imposed. On the assumption that work measurement is acceptable to both parties, then proposals are made as to the way in which group ‘Z’ will help the work study specialist who is concerned with measurement.

Although high morale (or team spirit) may at times be associated with low productivity, Likert argues that the kind of supervisory behaviour that results in high productivity also results in high work group morale. Where a work group has high morale it has greater control over its members and such control is exercised to achieve group goals. Management can never control as effectively as the group since ‘it is in almost constant contact with all its members and maintains an all-seeing surveillance of their activities; the informal group is self-policing and can relieve management of much of the burden of supervision when the group is co-operatively oriented.’ Where democratic leadership is exercised there is a greater likelihood that group goals and company objectives will coincide.

Does employee participation in decision-making reduce the influence exerted by the supervisor? Likert does not think so. He argues that when superiors have the sole authority for making decisions, they exert more influence on the decisionmaking itself but exert less influence on what actually goes on than when subordinates participate in decisions.

EVIDENCE

The most famous study indicating that people behave differently under different patterns of supervisory leadership was conducted by two psychologists, White and Lippitt.74 The investigation was concerned with four groups of children each containing five boys formed into ‘clubs’ built around the recreational activities of aeroplane model construction and similar hobbies. The boys in each group were matched with regard to background. Four group leaders were trained to act as democratic, authoritarian and laissez-faire leaders. As autocrats, the group leaders just told the children what to do and kept the group working. As democrats, the leaders were considerate and, although they gave a lead and help, they encouraged the group to decide issues as a group and to allocate work among themselves. As laissez-faire leaders, they simply indicated that they were available if wanted and then left the group to get on with the job. The group leaders moved from group to group at the same time changing their leadership pattern. The results are of interest. Under autocratic leadership, output was highest, but only when the leader was present. The group showed little initiative and was unimaginative. In addition, team spirit was low. Laissez-faire leadership gave the poorest results, output being both low and unimaginative. Under democratic leadership both morale and the quality of work was highest but output was slightly lower than under autocratic leadership.

The best-known work on supervisory behaviour in business was carried out by the Institute for Social Research whose Director is Rensis Likert. In one illustrative case, low-producing sections at the Prudential Insurance Company in the USA were compared with high-producing ones.75 As the sections were subject to the same working conditions and company policies, differences in output were assumed to be either due to the quality of management and supervision or to the social relations within the groups. A study was undertaken to test whether supervisory and management behaviour affected productivity through first of all affecting morale. The attitudes of worker and supervisor were measured and related to sectional efficiency. The analysis suggested that supervisors of high-producing sections tended to exhibit the employee-centred behaviour. A further study was carried out on maintenance-of-way groups on the railways. The findings were similar, except that the Prudential investigation found that high-producing supervisors exercised only general rather than close supervision of subordinates, whereas this was not confirmed in the second study. It appears that where the job to be done is simple relative to ability, close supervision is undesirable. On the other hand, where the job is non-routine, close guidance is welcome. In neither study did relations between group members account for differences in productivity.

The study was based on survey data rather than direct experimentation. However, Likert does quote one field experiment carried out at the insurance company by the Institute for Social Research. This study covered 500 clerical employees in four parallel divisions. Unfortunately, it was not conclusive. In fact, groups subjected to the more authoritative behaviour had a slightly higher productivity. Likert points out that adverse employee attitudes were developed in the group subject to the more authoritative behaviour. In the long run, he argues, if the experiment had continued, the difference in attitudes between the democratic and the authoritative would have made themselves felt so that the democratic group would have been more productive, since all other evidence points to this.

Likert comments as follows:

‘Apparently, the hierarchically controlled program, at the end of one year, was in a state of unstable equilibrium. Although productivity was then high, forces were being created, as the measures of the intervening variables and turnover indicated, which subsequently would adversely affect the high level of productivity. Good people were leaving the organization because of feeling “too much pressure on them to produce”. Hostility towards high producers and towards supervision, decreased confidence and trust in management, these and similar attitudes were being developed. Such attitudes create counterforces to management's pressure for high productivity. These developments would gradually cause the productivity level to become lower.’76

This argument is not impressive, Likert conducts an experiment because he recognizes the weakness of existing evidence; attitude survey data leaves many questions unanswered as to cause. Likert, however, interprets the results of the experiment in a way that presupposes that the existing evidence is already conclusive. Also a point which appears to have been treated lightly is the small differences investigated which were around 5 per cent. Such differences could be explained by the crudeness of the measurements of productivity between sections and through differences in work methods and quality standards, differences which could only have been revealed by a detailed method study. However, the evidence does indicate that democratic and employee-centred supervisory behaviour is as effective, if not better, than any other pattern of behaviour. As democratic behaviour may also lead to more adjusted subordinates, it isto be recommended.

All participative techniques for gaining co-operation owe most to Kurt Lewin and the School of Field Theory he founded. He also founded the Research Centre for Group Dynamics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology which is now under Likert at Michigan. The Group Dynamics movement has been responsible for developing most of the laboratory techniques for studying small groups. Some of Lewin's experiments demonstrate how attitudes and behaviour can be changed by participation. For example, during World War II, an attempt was made to change the way housewives were using meat. An expert lectured a group of women on the subject but only 3 per cent experimented with the suggested meats. In another group of like background, a discussion leader led the women in discussing the subject among themselves, and all participated in formulating conclusions. A follow-up showed that 32 per cent of the women had tried the foods previously rejected.77

One industrial experiment was carried out at the Harwood Manufacturing Company in Virginia, USA, by Lewin and some of his followers, Bavelas, French and Coch. A problem facing management was resistance to job changes, frequently accompanied by a drop in output. At the time of the experiment several minor but comparable job changes were needed. One group affected by these changes was selected as the control group and so given the usual treatment. When changes were introduced the production department changed the job and set a new piece rate, then the workers in the group were called together and told that the change was necessary because of competitive conditions and the new piece rate was explained. After questions had been answered, all the control group returned to work.

Changes were also introduced in work being carried out by three other groups called the experimental groups. Before any changes were made, the supervisor called together those affected. The problem was explained to the group and was discussed by them. A number of suggestions were made and the group agreed that savings could be made by eliminating ‘frills’; they agreed that a method study specialist should analyse the work and that they would try any new methods suggested. The groups were also given the opportunity to participate in proposed changes. One group participated in changes by having group representatives act on their behalf, but all members in the other two groups participated in planning job modifications.

There was a dramatic difference in results between the control and experimental groups. The production of the control group actually dropped and output had still not recovered at the end of the forty-day trial period. There was also considerable resentment about the new piece rate, though later examination showed this to be more loose than tight. In the two groups where full participation was used, output increased in the forty-day experimental period to a level that was about 14 per cent higher than the group had ever previously attained. The new piece rate was accepted and there were no signs of frustrated behaviour. The group which participated through representation increased output but by less than 14 per cent.

Also at Harwood another experiment was carried out by Bavelas in which small groups of workers (four to twelve workers in each group) were brought together under a leader who led a discussion on the advantage of team work. The leader put it to the group that they might like to set higher output goals for themselves and each group eventually agreed. As a result, output from these groups was increased by around 18 per cent, whereas output remained the same for other matched groups who were not involved in these discussions.

Viteles comments on the Harwood experiments as follows:

‘The design for neither study, as reported by the investigators, eliminated the possibility that variables other than participation in decision-making played a role in accounting for the production differences between the control and the experimental groups.

‘Of special importance, in the first of these studies, is an apparent difference in the character of the training received by operators in the two groups. While none of the available reports on this study are particularly clear with respect to this issue, it quite definitely appears that more and better training was received by members of the experimental groups than by members of the control groups. In the second study, as reported by French, it seems quite evident that each of the experimental groups was supplied with considerable knowledge of results, in the form of graphs showing changes in the productivity of the group. There is no indication that similar information was supplied to the control groups.... Failure to control adequately the possible effects of difference in training, in knowledge of results (and possibly of other variables) makes it impossible to accept the view that the increased output by the experimental groups in the Harwood plant studies was necessarily due solely to employee participation in decision-making. Nevertheless, the general nature of the experiments and of findings from these and other studies still support the view that employee participation in decision-making can contribute to increased employee productivity.’78

CRITICISM OF GROUP PARTICIPATION

Group participation in decision-making in the way described has been criticized on a number of grounds.

(i) Group participation gives the work group more power over its members. This may lead to a tyranny which is far worse than the autocracy of management.

(ii) It may result in decisions that run counter to the best judgment of experts. No adequate explanation has been given as to why participation should necessarily lead subordinates into adopting organization goals as their own.

(iii) It blurs responsibilities and individual accountability for performance.

(iv) It may lead to greater motivation and morale but not to greater productivity as the existing technology may set an upper limit to this.

(v) The gains from participation may be far less than the cost of changing supervisory patterns of behaviour and the cost of time consumed in committee.

(vi) Group participation may be ineffective unless supervisors and managers have the right attitudes; true participation cannot be imposed but must evolve naturally from the attitudes and values held by supervisors and managers. These may need to be changed through counselling. The emphasis here is placed on changing people rather than changing procedures or organization structures. Thus Argyris argues ‘The development of skills without appropriate changes in values becomes, at best, an alteration whose lack of depth and manipulative character will become easily evident to others. Skills follow values; values rarely follow skills.’79

(vii) Strauss, of the University of Calixornia, Berkeley, stresses the current weaknesses in research. ‘Considering the rather limited amount of research done, there is too much loose talk about the “proven” superiority of group-decision and participative methods. The studies cited chiefly involved women in war-time (food change), partially industrialized mountain folk (Harwood), and undergraduate students in psychology. Further research should involve various kinds of groups, various types of tasks, and various forms of participation.’80

THEORY ‘x’ AND THEORY ‘y’

Sometimes the results of a series of different experiments can be brought together and shown to be simply applications of a more general rule. This more general rule is called a ‘theory’. McGregor of Massachusetts Institute of Technology makes a distinction between what he terms Theory X and Theory Y.81 Both theories represent different views as to man's nature.

Theory X assumes that:

1. The average man is by nature indolent—he works as little as possible.

2. He lacks ambition, dislikes responsibility, prefers to be led.

3. He is inherently self-centred, indifferent to organizational needs.

4. He is by nature resistant to change.

5. He is gullible, not very bright, the ready dupe of the charlatan and the demagogue.82

Behind Theory Y is the view that:

1. People are not by nature passive or resistant to organizational needs. They have become so as a result of experience in organization.

2. The motivation, the potential for development, the capacity for assuming responsibility, the readiness to direct behaviour towards organizational goals are all present in people. Management does not put them there. It is a responsibility of management to make it possible for people to recognize and develop these human characteristics for themselves.

3. The essential task of management is to arrange organizational conditions and methods of operation so that people can achieve their own goals best by directing their own efforts towards organizational objectives.83

A number of recommendations made by McGregor and others rest on the assumption that people are not inherently indolent and so on, but became so through their treatment.

‘The social scientist does not deny that human behaviour in industrial organization today is approximately what management perceives it to be. He has, in fact, observed it and studied it fairly extensively. But he is pretty sure that this behaviour is not a consequence of man's inherent nature. It is a consequence rather of the nature of industrial organizations, of management philosophy, policy, and practice. The conventional approach of Theory X is based on mistaken notions of what is cause and what is effect.’84

McGregor in this passage implies that people's conduct must either be the cause or the effect of classical management policies. This is a fallacy. Both management practices and people's behaviour can modify and affect each other. Mental illness can cause physical illness; but physical illness can also cause mental illness.

Every business organization is composed of a number of work groups. Inter-group behaviour is concerned with the relations between these groups as they are a factor in achieving overall company objectives; a high level of achievement may require a high level of co-operation and co-ordination among groups.

A famous study on inter-group behaviour was that carried out by W. F. Whyte in 1944.85 He studied inter-group relations in a restaurant and found that where lower status workers, such as waitresses, made direct demands on higher status workers, such as cooks, then conflict resulted and efficiency was lowered. Whyte concluded that the normal flow of demands in inter-group relations should not flow from lower to higher status groups but vice versa if conflict is to be reduced. Thus cooks did not expect to be given orders by waitresses. Conflict was reduced when an impersonal barrier, namely a spindle on which waitresses placed their food orders, was erected between cooks and waitresses.

A further study of interest was made by Sherif.86 He found that conflict among groups could be reduced by introducing ‘superordinate’ goals, that is to say goals desired by the two or more groups in conflict but which cannot be achieved except by the combined efforts of all.

The conclusions from both the above studies have considerable intuitive appeal. Different groups need shared values and goals if they are to co-operate. A conflict between sales and production may arise because the two feel no strong sense of common purpose. It is also a matter of common observation that where demands flow contrary to status lines—from lower status to higher status groups—conflict arises unless steps are taken to avoid it by:

(i) Creating intermediary groups to act in a liaison capacity, such as production planning between sales and production or product planning between Sales and Research Development. In both these cases, the difference in status may be imaginary, each department believing itself the superior one.

(ii) Allocating a low-status member of the high-status group to deal with the low-status group (the shop steward has to see the foreman, not the manager).

(iii) Indicating that the lower status member is acting on behalf of a high-status member. A young specialist demanding information in a department may be resented unless it is made clear that he is acting on behalf of higher management.

HUMAN RELATIONS AND CLASSICAL ORGANIZATION PROBLEMS

GROUPING INTO SECTIONS AND HIGHER ADMINISTRATIVE UNITS

Flat versus Pyramidal Structure

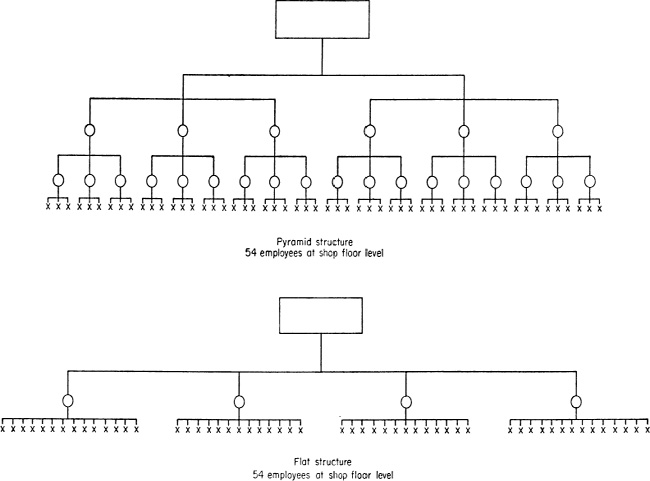

The human relations school stresses the importance of minimizing the number of vertical levels in an organization. A flat structure as opposed to a pyramid structure is recommended (Fig. 21).

(i) The fewer the levels, the more authority is pushed downwards, thus giving more discretionary authority to first line supervisors who may otherwise appear ineffective to those they supervise.

(ii) Communications are more effective.

(iii) Supervisor/subordinate relationships need to be less formal.

(iv) Drucker (not a member of the human relations school) states the defects of the pyramid structure as follows:

‘Every additional level makes the attainment of common direction and mutual understanding more difficult. Every additional level distorts objectives and misdirects attention. Every link in the chain sets up additional stresses, and creates one more source of inertia, friction and slack.

‘Above all, especially in the big business, every additional level adds to the difficulty of developing tomorrow's managers, both by adding to the time it takes to come up from the bottom and by making specialists rather than managers out of the men moving up through the chain.

‘In several large companies there are today as many as twelve levels between first-line supervisor and company president. Assuming that a man gets appointed supervisor at age twenty-five, and that he spends only five years on each intervening level—both exceedingly optimistic assumptions—he would be eighty-five before he could even be considered for the company's presidency. And the usual cure—a special promotion ladder for hand-picked young ‘geniuses’ or ‘crown princes’—is worse than the disease.

‘The growth of levels is a serious problem for any enterprise, no matter how organized. For levels are like tree rings; they grow by themselves with age. It is an insidious process, and one that cannot be completely prevented.’87

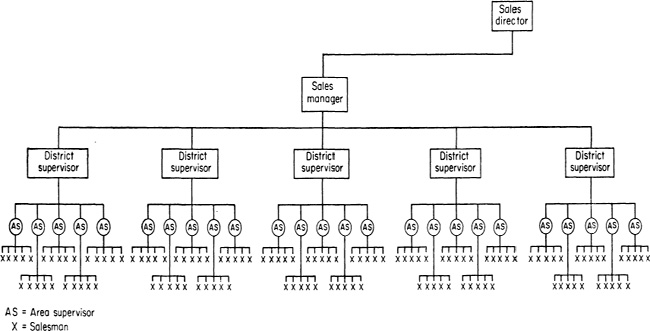

A flatter organization structure may be brought about by delegation, simplifying decision-making, de-centralization and forming sub-units with different managements. For example, one field sales force had the structure in Fig. 22.

In brief, it was found that much of the work of the District Supervisors could be done more efficiently by clerks at Head Office. Other work could be passed on to Area Supervisors, if policy was more explicitly stated, and more decisions could be made by the salesmen.

After the investigation, a reason given for still justifying the District Supervisor level was that it created greater opportunities for promotion and thus the more able salesmen were retained. However, the increased promotion opportunity meant that the good salesmen were lost anyway as they were promoted. Promotion, too, must have led to much disappointment since so much of the managerial work was of a routine clerical nature. In addition, selling costs were excessive and the very existence of levels made everyone promotion-conscious in a desire to be closer to the man who had the ultimate say.

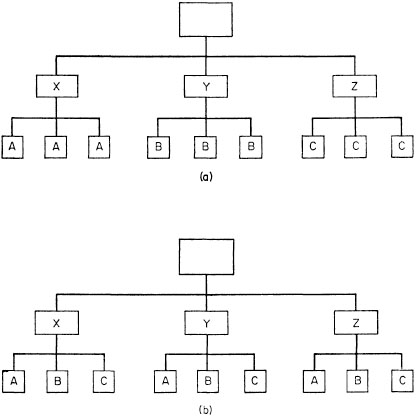

Sectional Over-specialization

In thesame way that high-task specialization can narrow the man, the human scientist argues that it is also possible for a department or section to over-specialize so that its contribution to overall company goals becomes blurred. In such circumstances, sectional or departmental goals may be at variance with the best interests of the company. Fig. 23(a) illustrates the position. The figure shows three departments each divided into three sections. Each section is carrying out identical work, as illustrated by the similarity of letters in the boxes. There is a strong need for co-ordination if each department is not to go its own way.

An alternative organizational arrangement is shown inFig. 23(b) where each department is independent, being made up of each of the three different types of sections. Such an organizational arrangement may achieve a better integration of the three distinct activities, but it may also lead to losses arising through activities being carried out on a smaller scale or through there being less opportunity for specialization.

Choice of Supervisor

The importance of choosing supervisors who allow participation and are employee-centred has already been discussed.

Choice of Team Members

Sociometric methods have been used to fit work teams together. One case has already been quoted. One published study involved seventy-two carpenters and bricklayers on a housing project. Each was allowed to choose his team mates to form eighteen four-man work teams. Twenty workers were given their first choice, twenty-eight had their second choices, sixteen obtained their third choices and the eight isolates were distributed over the groups. As a result labour turnover decreased from 3·11 leavers per month to 0·27 and labour costs were decreased.88

FIG. 23.—(a) Original organization. (b) Alternative suggested.

One major difficulty, however, in using sociometric methods for team selection is that teams of unequal ability and capacity may result.

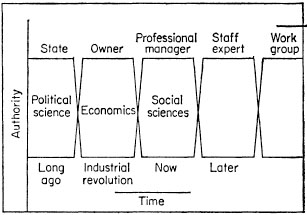

The Link-pin Theory

If problem-sharing between superiors and supervisors and between supervisors and employees is an effective way of integrating work group goals and organization goals, then each supervisor and superior should belong to two different levels of work group; the work group composed of his subordinates and a work group which includes his own boss. Such considerations lead Likert to suggest that management should build up work groups and link them in the overall organization by means of people who hold overlapping group membership. This has come to be known as the ‘link-pin theory’ though Likert prefers to call it the ‘interaction influence system of management.’89 His ideal organization would be composed of overlapping work groups in which some people act as ‘link-pin’ members. The position is illustrated in Fig. 24.

FIG. 24.—Rensis Likert's overlapping Work Group Structure. (After Mason Haire (ed.), Modern Organization Theory, p. 193, John Wiley, London & New York.)

The superior in the bottom group is a subordinate in the next group and so on through the organization. Specialists would also be integrated into these work groups and the groups used for decision-making and not simply for communication. Likert does not use the term ‘committee’ since committees do not necessarily allow the full participation which would be essential to effective functioning.

Likert's link-pin theory has been critized even by fellow-psychologists. Robert Dubin, a sociologist at Oregon, condemns the overlapping group form of organization on the ground that it is often wasteful and slow.

‘At the level of linking organization units, the analogical application of the group-dynamics precept leads to a preference for circular linkage-systems. This takes the typical form of permanent committees made up of unit representatives, ad hoc committees, periodic meetings of representatives of “interested” units, or the persistent demand that everybody be “kept informed” of developments in each unit. The volume of activities involved in this togetherness, as well as the gamesmanship employed to carry it through, is what has given rise to Parkinson's Law, and parallel, but less exact formulations of it.’90

A more serious criticism of Likert's theory is that it presupposes that co-operation is the sole factor that is needed to optimise a business situation. Group participation, in any case, is not always best. Even Likert emphasizes that people should not participate beyond their expectations. Many decisions, too, made by managers do not affect directly any work group, for example those on company insurance. An excellent guide to deciding the appropriateness of group decision-making is the following set of criteria established by Robert Tannenbaum and Fred Massarik.

‘1. Time Availability. The final decision must not be of a too urgent nature. If it is necessary to arrive at some sort of emergency decision rapidly, it is obvious that even though participation in the decision-making process may have a beneficial effect in some areas, slowness of decision may result in thwarting other goals of the enterprise or even may threaten the existence of the enterprise. Military decisions frequently are of this type.

2. Rational Economics. The cost of participation in the decisionmaking process must not be so high that it will outweigh any positive values directly brought about by it. If it should require outlays which could be used more fruitfully in alternative activities (for example, buying more productive though expensive equipment), then investment in it would be ill-advised.

3. Intra-Plant Strategy

(a) Subordinate Security. Giving the subordinates an opportunity to participate in the decision-making process must not bring with it any awareness on their part of unavoidable catastropic events. For example, a subordinate who is made aware in the participation process that he will lose his job regardless of any decisions towards which he might contribute may experience a drop in motivation. Furthermore, to make it possible for the subordinate to be willing to participate, he must be given the feeling that no matter what he says or thinks his status or role in the plant setting will not be affected adversely. This point has been made effectively in the available literature.

(b) Manager Subordinate Stability. Giving subordinates an opportunity to participate in the decision-making process must not threaten seriously to undermine the formal authority of the managers of the enterprise. For example, in some cases managers may have good reasons to assume that participation may lead non-managers to doubt the competence of the formal leadership, or that serious crises would result were it to develop that the subordinates were right while the final managerial decision turned out to be in disagreement with them and incorrect.

4. Inter-Plant Strategy. Providing opportunities for participation must not open channels of communication to competing enterprises. “Leaks” of information to a competitor from subordinates who have participated in a given decision-making process must be avoided if participation is to be applicable.

5. Provision for Communication Channels. For participation to be effective, channels must be provided through which the employee may take part in the decision-making process. These channels must be available continuously and their use must be convenient and practical.

6. Education for Participation. For participation to be effective, efforts must be made to educate subordinates regarding its function and purpose in the over-all functioning of the enterprise.’91

There is a reluctance to concede that the more powerful the work group becomes, the more the pressure to conform increases on any ‘odd man out’ and, in the process, both his happiness and freedom are reduced. Participation is also difficult to structure in practice, and this difficulty partly arises because there is doubt about the motives which participation is meant to satisfy. The following are possible.

(i) It satisfies some need for affiliation or some desire to associate with one's colleagues.

(ii) It satisfies the desire to feel of some consequence by giving people a say in their own destiny. Participation brings about a more uniform distribution of power in an organization, and as a consequence, autocratic behaviour is more difficult.

(iii) Participation by eliminating extreme viewpoints through social pressure brings about a reconciliation of viewpoints.

(iv) It leads managers to consider the perceptions of the man on the shop floor and so take them into consideration when planning changes. For example, technological changes may be resented, not because progress itself is resented, but because such change can alter existing social relationships.

Determining which of the above is most important will decide the approach to achieving participation. Until deeper analysis is forthcoming, it is best to regard participation as involving all the above aspects.

DELEGATING AUTHORITY

Definition of Authority