11

Currency Exchange Trading and Rogue Trader John Rusnak

Sharon Burke

INTRODUCTION

In 1993, a foreign currency trader, John Rusnak, was hired by Allfirst bank in Maryland. John Rusnak was hired to bring profits to Allfirst via proprietary foreign exchange trading. Prior to Rusnak's arrival, foreign exchange trading at the bank was limited to assisting bank customers in hedging against currency risk. Allfirst performed this service for companies that were dealing with overseas trades.

This decision would eventually incur a $691 million loss for Allied Irish Bank, the owner of Allfirst bank. The story of this loss involves foreign exchange trading, bank organization, organizational politics, inadequate accounting controls and more. This article will include a review of foreign currency trading concepts, the strategies that Rusnak employed to trade and to cover his losses and the findings of the subsequent investigation by Eugene Ludwig.

CURRENCY MARKETS

The foreign currency market is virtual. That is, there is no one central physical location that is the foreign currency market. It exists in the dealing rooms of various central banks, large international banks, and some large corporations. The dealing rooms are connected via telephone, computer and fax. Some countries co-locate their dealing rooms in one centre. The Eurocurrency market is one example of where borrowing and lending of currency takes place. Interest rates for the various currencies are also set in this market.1

Trading on the foreign exchange market (FOREX) establishes rates of exchange for currency. Exchange rates are constantly fluctuating on the FOREX market. As demand rises and falls for particular currencies, their exchange rates adjust accordingly. Instantaneous rate quotes are available from information services like Reuters. A rate of exchange for currencies is the ratio at which one currency is exchanged for another.2

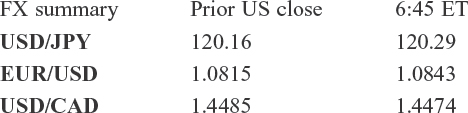

The following are examples of currency rates from the Wall Street Journal on April 16, 2003:3

This shows the closing exchange rates from the foreign exchange market. For example, the USD/JPY value is the exchange rate for US dollars to yen, that is, 120.16 yen per one US dollar. The US dollar is the base currency in this case, as it is one unit of a US dollar per an amount of yen.

The foreign exchange market has no regulation, no restrictions or overseeing board. Should there be a world monetary crisis in this market; there is no mechanism to stop trading.4 The Federal Reserve Bank of New York publishes guidelines for foreign exchange trading. In their “Guidelines for Foreign Exchange Trading”, they outline 50 best practices for trading on the FOREX market.5 This document is not legally binding or regulatory in nature.

EXCHANGE CONTRACTS

The actual exchange of currencies is governed by contracts between the buyer and seller of the currencies. There are a variety of contract options available to investors. Rusnak focused on spot and forward contracts in his trading.

SPOT EXCHANGE

The spot exchange is the simplest contract. A spot exchange contract identifies two parties, the currency they are buying or selling and the currency they expect to receive in exchange. The currencies are exchanged at the prevailing spot rate at the time of the contract. The spot rate is constantly fluctuating. When a spot exchange is agreed upon, the contract is defined to be executed immediately. In reality, a series of confirmations occurs between the two parties. Documentation is sent and received from both parties detailing the exchange rate agreed upon and the amounts of currency involved. The funds actually move between banks two days after the spot transaction is agreed upon.6

FORWARD EXCHANGE

The forward exchange contract is similar to the spot exchange; however, the time period of the contract is longer. These contracts use a forward exchange rate that differs from the spot rate. The difference between the forward rate and the spot rate reflects the difference in interest rates between the two currencies. This prevents an opportunity for arbitrage. If the rates did not differ, there would be a profit difference in the currencies. That is, investing in one currency for a year and then selling it should be the same profit or loss as setting up a forward contract at the forward rate one year in the future. If investing in one currency was more profitable than investing in the other, there would exist an opportunity for arbitrage.7 Forward exchange contracts are settled at a specified date in the future. The parties exchange funds on this date. Forward contracts are typically custom written between the counterparty and the bank, or between banks.

CURRENCY FUTURES AND SWAP TRANSACTIONS

Currency futures are standardized forward contracts. The amounts of currency, time to expiry, and exchange rates are standardized. The standardized expiry times are specific dates in March, June, September, and December. These futures are traded on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME). Futures give the buyer the ability to set up a contract to exchange currency in the future. This contract can be purchased on an exchange, rather than custom negotiated with a bank like a forward contract.8

A currency swap is an agreement to two exchanges in currency, one a spot and one a forward. An immediate spot exchange is executed, followed later by a reverse exchange. The two exchanges occur at different exchange rates. It is the difference in the two exchange rates that determines the swap price.9

OPTIONS

A currency option gives the holder the right, but not the obligation, either to buy (call) from the option writer, or to sell (put) to the option writer, a stated quantity of one currency in exchange for another at a fixed rate of exchange, called the strike price. The options can be American, which allows an option to be exercised until a fixed day, called the day of expiry, or European, which allows exercise only on the day of expiry, not before. The option holder pays a premium to the option writer for the option. The option differs from other currency contracts in that the holder has a choice, or option, of whether they will exercise it or not. If exchange rates are more favorable than the rate guaranteed by the option when the holder needs to exchange currency, they can choose to exchange the currency on the spot exchange rather than use the option. They lose only the option premium. Options allow holders to limit their risk of exposure to adverse changes in the exchange rates.

CURRENCY HEDGING

It is common for currency options to be used to hedge cash positions. For example, if Company A is buying stereos from Japan, they will make an agreement to pay Company B for the stereo equipment in yen. The spot rate at the time of the deal is 119Y to the US dollar. Suppose that the stereos are selling for $100.00 each or ¥11,900 a piece. The company is purchasing 100 stereos. They need to provide ¥1,190,000 to the seller. If the stereos were purchased today, they would cost the company $10,000. The company would exchange $10,000 for ¥1,190,000.

This deal will be transacted in three months. In three months, currency rates will change. If the US dollar falls against the yen, for example, the spot rate for yen in exchange for US dollars may be ¥100 to the dollar. In that case, in order to provide ¥1,190,000 to the seller of the stereos, the company must exchange $11,900. The deal costs an extra $1,900. However, if the yen falls against the US dollar, the spot rate might become ¥130 per US dollar. In that case, the ¥1,190,000 needed to close the deal will cost $9,154. The company has saved $846.

Companies are not typically in the business of gambling with their profits on deals. It is in their best interest to lock in an exchange rate they can count on. They are motivated to insure that their profits are as expected. Two ways they might do this are to enter forward contracts or to buy options. Company A could choose to enter into a forward contract with a bank. They would settle on a forward rate that was acceptable to both parties. The contract would settle in three months when the delivery was due. The forward contract is a binding contract and they must make the exchange.

The company could also assess the interest rates available in the US and in the Eurocurrency market. They could either invest $10,000 in the US for 3 months, or exchange $10,000 into yen and invest the ¥1,190,000 for 3 months.

Company A could also use options to reduce their exposure to currency fluctuation. The company will need yen to pay for the stereos. They could purchase a call option to exchange ¥1,190,000 with an expiry date of 3 months. They would select an exchange rate that would be acceptable but not too expensive. They might choose to buy a slightly out-of-the-money call option to cover them if the currency exchange rate falls. If it stays the same or rises, they will exchange at the spot exchange rate at the time the payment is due.

TRADING STRATEGY OF JOHN RUSNAK

The foreign currency market is the market that John Rusnak gambled and lost in. He used spot transactions, forward transactions and options to amass losses of $691 million. Rusnak had been employed in foreign currency trading beginning in 1986 at Fidelity Bank in Philadelphia. He worked at Chemical Bank in New York from 1988 to 1993. In 1993, he was looking for a new position. Coincidentally, David Cronin, the Treasurer of Allfirst Bank in Maryland was looking for a new foreign currency trader. Cronin was originally from Ireland. He had come to the U.S. to represent the interests of Allied Irish Bank when they had purchased Allfirst. Allfirst was formerly known as First National Bank of Maryland.

Rusnak proposed a trading strategy that sounded new and inventive. He told Cronin, “… he could consistently make more money by running a large option book hedged in the cash markets, buying options when they were cheap and selling them when they were expensive.”10 The Ludwig Report, a report commissioned by AIB to determine the extent of Rusnak's fraud, states that “Mr. Rusnak promoted himself as a trader who used options to engage in a form of arbitrage, attempting to take advantage of price discrepancies between currency options and currency forwards.” In order to execute this strategy, Rusnak would have had to buy options “… when they were cheap relative to cash (when the implied volatility of the option was lower than its normal range) and sell them when they were expensive (when the implied volatility is higher than normal).”

In his trading, Rusnak did not achieve these lofty goals. Rusnak executed simple directional trades on the spot and forward markets. He mostly traded in yen and euro. Occasionally, he would use complex options.11 Rusnak placed large sum one-way bets that the yen would increase in value against the US dollar. Specifically, he bought yen for future delivery, probably with forward contracts. As the yen declined, he could not go back on the forward contracts as they are binding, and was forced to take his losses. He did not hedge these bets with options contracts.

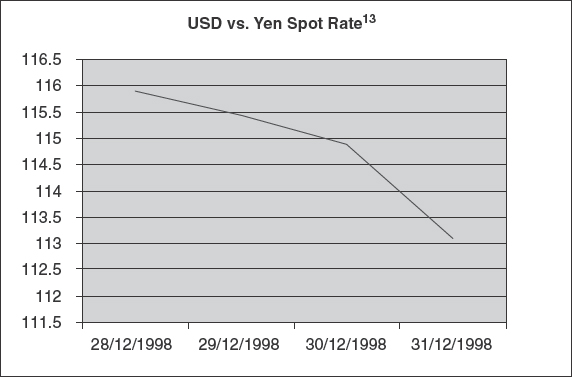

Rusnak's core trading belief was that the yen was going to rise against the US dollar. His strategy throughout all his trading was to place bets in this direction. It is interesting to note what was happening with the yen during the time period Rusnak was trading. From 1990 to 1995, the yen appreciated. From mid-1995 to 1997, the yen was depreciating against the dollar. In April of 1997, the exchange rate was around 125 yen to the US dollar. The Asian market crisis followed soon after causing further problems for the yen.12 As the yen depreciated, Rusnak began to have great problems with his one-sided trading.

At the end of 1997, Rusnak had lost $29.1 million by his wrong bets in trading. The jargon of gambling suits his activities well. After his losing bets and heavy losses, Rusnak embarked on a path to cover up those losses. Instead of taking responsibility and reporting his losses immediately, he decided to hide them, buy himself some time and see if he could win back the money he had lost. He used many complicated schemes to hide his losses. They included falsification of documents, misuse of office technology and fraudulent entries in accounting systems.

BOGUS OPTIONS

The first technique Rusnak used to hide his losses was to enter bogus options in the banking system. The purpose of these fake options was two-fold. The options appeared to hedge his directional trades. They also gave him a way to hide the losses with a bogus asset. At the end of his trading day, when Rusnak was entering his daily trades in the bank system, he would enter two false trades. He would enter two options that would offset each other. The options had the same premium in identical currencies. They were for the same amounts of currencies and used the same strike price. The expiry dates on the options were different.

For example, Rusnak would enter a put option “sold” by Allfirst to a party in Tokyo. The option would allow the Japanese bank to sell yen at a certain strike price. This option would expire on the day it was written. He would also enter a call option written by the Japanese bank to buy yen at the same strike price as the other option. This option would expire months in the future. The put option would disappear off the books the next day, removing that liability from the bank's records. The call option would stay on the books as a valuable asset that covered his losses.14

It was important to have the premiums of the two options exactly cancel each other out. If the options had not canceled out to zero, there would have been a payment due to either Allfirst or to the counterparty in Tokyo. All payments were required to go through the treasury department's back office. Keeping the premiums the same meant there was no net payment and thus no requirement for the back office to be involved in payment. Anyone who really looked at the options would have questioned the fact that the two options had different expiry dates but the same premium. That did not make sense. Also, the put option was a deep-in-the-money option. The holder of the option would make a profit by exercising it. The option went off the books in one day unexercised. That was unusual and did not make sense.15 It is probable that the call option was also deep-in-the-money.16 There were several of these options that the bank had “paid” high premiums for. The high premium indicates they were probably deep-in-the-money options. Their high value was necessary to cover the high losses that Rusnak was incurring. The fake option trades were written in the opposite direction of the losing bets he placed. This made it appear to Allfirst that he had offset his losses.17

FALSIFIED DOCUMENTS

The bogus options solved one problem, covering the losses; however, they created another problem. The back office was responsible for confirming all trades. The foreign exchange operation at Allfirst was operating on a shoe-string compared to what a large bank would have in place. Typically a true foreign exchange operation has research departments, dealing rooms, computer programs that automatically confirmed trades and a more sophisticated set-up. Allfirst was using telephone and fax to execute and confirm trades.

Rusnak knew that the back office was going to need to confirm his trades. He used his PC to create false trade confirmation documentation. His PC was discovered to have a directory called “fake docs”. This directory contained logos and stationery from various banks in Tokyo and Singapore. Rusnak used these files to construct fake confirmation documents on his computer. He was able to convince the back office to accept these documents from him, rather than confirming the trades themselves as required.18 Eventually, Rusnak was able to convince the back office to not confirm the trades at all. He was able to argue that since the trades netted to zero, they did not need to be confirmed. This argument was probably acceptable given that confirming Asian trades with their system would have required night-time phone calls. Some in the company say that it was a senior management decision to not confirm Asian counter party trades that netted to zero. The Ludwig report indicates that no evidence of this management decision could be found.19

PRIME BROKERAGE ACCOUNTS

In 1999, with $41.5 million lost, Rusnak turned to prime brokerage accounts. He needed to increase the size of his trades so he could catch up on his losses. Prime brokerage accounts are typically used by high profile traders. They are very often used by hedge funds.20 The prime brokerage accounts provided Rusnak with net settlements. Daily spot transactions were rolled into one forward transaction to be settled at a future date with the prime broker. This accomplished several things for Rusnak. Having all the daily spot transactions rolled into one net settlement meant that the back office could not track his daily trades as effectively. It was a means of obscuring what he was really doing.

Rusnak was able to expand the scale and scope of his trading to large volume high value currency trades.21 He needed to be able to do this to win back the large amounts of money that he was losing. Rusnak was able to convince David Cronin, the Allfirst Treasurer, that the prime brokerage accounts were a sound idea. He sold them as a way of growing Allfirst's foreign exchange operation. He also said that using the prime brokerage accounts would relieve the back office of the extra work they needed to do on his behalf. His false concern for the back office is quite interesting in light of how often he was at odds with that department over his trading practices. Rusnak used the prime brokerage accounts as another opportunity to enter fictitious trades. He could enter fictitious trades with the brokerage banks to further manipulate the bank's records. He would reverse these transactions by month end before the monthly settlement was done.22

The prime brokerage accounts allowed Rusnak to use a type of foreign exchange contract called a “historical rate rollover.” This type of contract was invented to assist companies in handling delayed shipments from foreign companies. It is a method to extend a currency contract in the event that a settlement of the contract would create a loss for the contract holder. For a purchaser of goods, when the goods are delayed, it can be convenient to extend a contract and wait to exchange funds until the time payment is required.

However, for a trader, these types of contracts allow losses to be rolled forward. If the trader's contract is due to be settled, and settlement would not be in his favour, he can delay settlement and keep the original rate of the contract. The New York Times reports “The rollover buys time for a trader who hopes that the currency rates will change in his favour in the future. The risk, of course, is that the losses will deepen …”23 For Rusnak, this was certainly the case. The historical rate rollover is warned against in the Federal Reserve Bank of NY standard of conduct:

“Accommodation of customer requests for off-market transactions (OMTs) or historical rate rollovers (HRROs) should be selective, restricted, and well documented, and should not be allowed if the sole intent is to hide a loss or extend a profit or loss position. Counterparties should also show that a requested HRRO is matched by a real commercial flow.”24

The Federal Reserve had been warning against the HRROs since 1991. The use of historical rate rollovers by Rusnak should have alerted his trading partners that something was suspicious.25

VALUE AT RISK CALCULATIONS

Rusnak avoided detection by manipulating the bank's Value at Risk (VaR) calculations. Value at Risk can be calculated using the Monte Carlo simulation technique. One thousand hypothetical exchange rate fluctuations are generated. Those rate fluctuations are applied to the trader's portfolio. The tenth worst outcome produced may be used as the bank's Value at Risk.

The VaR is the main check used on traders to make sure they are not losing more than the bank can afford to lose. A VaR limit is the largest amount of money the bank is prepared to lose if there are adverse trading conditions. For Rusnak, the VaR limit was $1.5 million. As of the end of 1999, Rusnak had lost $90 million. He had clearly found a way around this check.

A trader is responsible for calculating and monitoring their own VaR. The VaR is also independently calculated by treasury risk control as a check on the trader. The bogus options discussed earlier made Rusnak's open forward positions look as if they were hedged. This improved his VaR as it made his portfolio seem less risky. The fictitious prime brokerage account transactions he was entering also obscured his true VaR. He was able to convince the risk control group to accept a spreadsheet of his open currency positions from him with no confirmation. He altered the values in this spreadsheet to make his open positions seem less than they were. And since the risk control group did not confirm these values, he got away with this technique.

Rusnak was able to take advantage of technology and cost cutting measures to obscure his stop-loss limit. The stop-loss limit was an amount of loss, after which, Rusnak's trading would have been shut down for the month. Rusnak could not afford to lose any time in trying to win his losses back. He had to find a way around the stop-loss limit because he was regularly exceeding it. Rusnak found that he could manipulate the currency exchange rates used by the bank to produce calculations that made it look like he had not exceeded his stop-loss limit. Again, he was able to provide his own spreadsheet with the exchange rate values. These exchange rates were supposed to be independently confirmed by the risk management office of Allfirst's treasury.26

Rusnak had convinced the computer operations department to download exchange rate data from Reuters onto his PC. He claimed he needed to have these rates downloaded to his system so he could monitor his VaR. From his PC, a spreadsheet was then forwarded to the systems in the treasury front and back offices. All of the bank's foreign exchange rates were passing through Rusnak's hand before being fed into the computer system. This was a serious breach of the integrity of the bank's systems. One of the reasons this happened was that the bank did not want to pay $10,000 for an additional feed from Reuters for the back office.27 This additional feed would have enabled the back office to independently confirm exchange rates and check Rusnak's calculations.

SALE OF OPTIONS

By the end of 2000, Rusnak had lost $300 million. He was getting pressure from his superiors to reduce his use of the company's balance sheet. The balance sheet of a company lists their assets, liabilities and stock holder's equity at a given time. It shows the resources the company has available to it for operating activities and investment.28 David Cronin was taking notice of the large amount of the balance sheet Rusnak was using. Foreign exchange trading revenue was $13.6 million. The net trading income, however, was only $1.1 million. Rusnak was using more of the balance sheet but getting less in return. Cronin asked Rusnak to reduce his use of the balance sheet.

Rusnak needed large amounts of cash to continue his gamble to win back the money he had lost. Having his balance sheet usage restricted was somewhat of a blow. To get around this restriction and continue his quest to win back his losses, he came up with a plan. He would sell deep-in-the-money options at high premiums to finance his trading. The options he sold had deep-in-the-money strike prices. The strike prices were so deep, it was extremely likely that the options would be exercised. They were European options that expired in a year and a day. They were essentially loans from the counterparties to Allfirst.

As an example, in February 2001, Rusnak made an agreement with Citibank. For a premium of $125 million, Rusnak wrote a put that gave Citibank the right to sell yen at a strike rate of 77.37 yen to the US dollar. The exchange rate at the time was 116 yen to the US dollar. The US dollar would have to fall 35% for the option to go unexercised. The option was effectively a high interest loan. The loan payment would come due as a lump sum with interest when Rusnak had to buy the yen that Citibank wanted to sell in one year's time. Rusnak had found another way to buy the time. However, it created a liability that was sitting on Allfirst's books. Rusnak entered a bogus deal with Citibank that made it appear that Allfirst had repurchased the option.29 Rusnak repeated this process with Bank of America, Deutsche Bank, Bank of New York and Merrill Lynch.30 The options he sold totalled over $300 million raising his total losses to $691 million, when the yen depreciated further.

LOSSES REVEALED

Rusnak avoided an amazing number of situations where he could have been caught. He avoided detection over a period of five years. In my research I found 12 separate occasions where his activities were questioned by the back office, the risk management department at Allfirst, the SEC, and the CEO of Allied Irish Bank. Rusnak was able to avoid detection on all occasions.

A particularly involved scheme occurred during an audit conducted at Allfirst during the five year time period of the fraud. Rusnak was asked to confirm an Asian trade that was bogus. He set up a fax account at Mailboxes etc. in Manhattan under the name David Russell. He gave the fax id code of that account to the auditors. The auditors faxed a confirmation request to that fax id. Rusnak then called the Mailbox etc. store, posed as David Russell and had them fax a return confirmation.

At one point, the bank gave Rusnak Travel Bloomberg software so that he could trade from home and while on vacation. This was a direct violation of U.S. law. U.S. law requires that traders take 10 consecutive days off from trading every year.31 This is specifically so someone else takes over their duties and fraud can be discovered.

Finally in December 2001, Rusnak's luck began to run out. A back office supervisor happened to look over the shoulder of an employee and saw that there were two trade documents from Asian trades that Rusnak executed that did not have attached confirmations as required.32 The supervisor discussed with the employee that all trades had to have confirmations. The employee believed that any Asian trades that netted to zero did not need to be confirmed. The supervisor requested that the employee get the trades confirmed. In late January, the supervisor again found that Asian trades that netted to zero were still not being confirmed. The back office had become lax and given up after years of losing battles over concerns with Rusnak's trading. Unfortunately, they were not getting the backing they needed to do their job. The back office employee did not bother to seek confirmations.

Around this time, David Cronin, the Allfirst treasurer, noticed that Rusnak's use of the balance sheet had spiked up to $200 million in January. Cronin had directed that it stay under $150 million. Also, Cronin discovered that the foreign exchange trading volume for the bank had been at $25 billion for the month of December. He decided to shut down Rusnak's trading positions for a month. Meanwhile, the back office requested Rusnak's help in obtaining confirmations for the Asian trades. Rusnak was able to stall for time and offered to get the confirmations himself. He resurrected his fake documents file and created false trade confirmations on his computer. When the trade confirmations were provided, the back office supervisor noticed that they looked suspicious.33

For the next week, Rusnak stalled. There was a day or two where the bank thought that he had disappeared. It later turned out that he had been conferring with his family, a lawyer and finally the FBI. He essentially turned himself in and cooperated. His most important task at that time was convincing the FBI that he had not embezzled the money, that he did not have it hidden anywhere. It had all been lost on the foreign exchange market. Rusnak had acted alone. He was charged with seven counts of bank fraud and entering false entries in bank records.34 He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 7½ years in prison and a $1 million fine.35

THE LUDWIG REPORT

Shortly after Rusnak's fraud was discovered, the Allied Irish Bank (AIB) Board of Directors authorized an investigation by Eugene Ludwig of Promontory Financial Group LLC of Washington DC. Eugene Ludwig had been Comptroller of the Currency from 1993 to 1998 under President Bill Clinton.36 He had a strong background in bank regulation. The Board needed to bring in an impartial party to investigate. They needed to restore the confidence of their shareholders.

When the news of Rusnak's fraud was reported, shares of AIB fell from €13.62 to €11.36 on the first day. AIB had been the largest capitalized company on the Dublin Stock Exchange with a capitalization of €12 billion.37 In one day it fell to €10 billion, losing AIB €2 billion in capitalization. AIB had been about to announce a profit of €1.4 billion ($1 billion) for 2001. The discovery of Rusnak's fraud reduced this to €612 million ($426 million).38 There were interviews in the media at the time with Nick Leeson, the trader whose losses had caused the fall of Barings Bank. Although there were many similarities to the two stories, AIB, unlike Barings, was able to absorb the loss.

Eugene Ludwig's team investigated Allfirst and Rusnak's fraud beginning on February 8, 2002. They published their report on March 12, 2002. The Ludwig team discovered what Rusnak had done to conceal his losses. They determined that he had worked alone. They identified the following failings in control at Allfirst and AIB that taken altogether, allowed Rusnak to commit fraud39:

- “The failure of the back office to attempt to confirm bogus options with Asian counterparties.”

- “The failure of the middle and back offices to obtain foreign exchange rates from an independent source.”

- “In 1999, an internal audit of treasury operations took no samples of Rusnak's transactions to see if they had been properly confirmed.”

- “In 2000, the internal audit sampled only one trade of Mr. Rusnak's to check if it was properly confirmed.”

In addition to these failures of control, the bank missed opportunities by ignoring problems raised by the back office. Employees in the back office raised issues ranging from problems confirming trades to warnings that there was a possibility that Rusnak could be manipulating foreign exchange rates. But Rusnak had been showing a yearly profit for five years straight. He became untouchable in organizational politics because he appeared to be so good. The back office staff eventually gave up raising flags on his trading practices as they were continually shot down by management.40 With executive backing, the back office could have performed a very valuable function and assisted with detecting Rusnak's fraud.

Rusnak's supervisors were not experienced in foreign exchange trading. They did not adequately supervise his activities. A knowledgeable supervisor would have seen that the deep-in-the-money bogus options expiring on the same day they were purchased were odd. The sheer size of Rusnak's positions warranted closer scrutiny. No one was monitoring Rusnak's daily profit and loss (P&L) figures. They were not reconciled against the general ledger.41 If this step had been taken, questions would have arisen as to why his daily P&L swung so widely from profit to loss and back.

There were many who had an opportunity to be aware of the size of Rusnak's positions. In 1999, a risk assessment auditor questioned the size of Rusnak's over limits. Citibank contacted AIB's Group Treasurer to confirm that AIB could cover a net settlement of $1 billion on Rusnak's prime brokerage account. The SEC 10k filings of Allfirst showed the size of Rusnak's positions. Credit limits were exceeded by Rusnak. There was a trader that worked with Rusnak who could have noticed the size of his positions and questioned it but didn't.42 The traders at the prime brokerage accounts also knew his positions. All traders should be aware of the foreign exchange trading guidelines. These guidelines outline suspicious trading activity. For example, the use of historical rate rollovers (HRRO) expressly states that HRROs should not be used to cover losses.43 Those who were watching the forex market came to recognize Rusnak's trades.44 There were many who knew or could have guessed the size of his positions and raised an alarm.

Following are some highlights of the Ludwig Report findings on what contributed to the fraud:

- “The architecture of Allfirst's trading activity was flawed.” They had one lone trader trying to essentially implement a hedge fund. He had none of the “specialized knowledge, scale, diversification and specialized expertise” that his competitors had.

- Senior management in Baltimore and Dublin did not focus sufficient attention on the Allfirst trading operation.

- Rusnak knew the banking systems well from his experience at Chemical Bank so he was able to circumvent their controls.

- Treasury management weaknesses at Allfirst also contributed to the environment that allowed Rusnak's fraud to occur. The Allfirst Treasurer had a dual reporting structure. David Cronin reported into Allfirst through a variety of different managers. He also reported into AIB. The CEO of Allfirst thought AIB was managing Cronin and vice versa. Therefore, the treasury operation was not managed as thoroughly as it should have been.

- Senior management at both Allfirst and AIB thought their control structures and auditing were more robust than they actually were. The risk reporting processes needed to be more robust. The risk management team needed to be more proactive in finding problems rather than dealing with what was presented to them.45

The Ludwig Report provides great detail into what happened at Allfirst and the various areas of laxity, weakness and fault that contributed to Rusnak's activities. The most significant were the failures in technology, the disorganization and the auditing and monitoring failures.

TECHNOLOGY

As the Ludwig report highlights, Allfirst was running a foreign exchange trading operation without the full backup needed to sustain the levels of trading Rusnak was involved in. Banks that trade in the volume Rusnak was trading in typically have a large support staff. There are individuals backing up the trader by doing market research. Traders are working in groups where it is more difficult to commit fraud. In particular, many larger trading organizations use the Crossmar Matching System to confirm trades. This system can confirm trades in effect instantaneously. Instead of using this state of the art computing system, Allfirst was using a system of telephone and fax communication.

The system suited a small state bank that traded occasionally to assist its clients when they needed a currency hedge. It was inadequate for the volume and size of the positions Rusnak was taking. The inadequate system left openings for John Rusnak to fake fax communications and create fake confirmation letters. It is of interest to note that Allfirst felt the Crossmar matching system was too expensive to implement for only two foreign exchange traders.46

A glaring technology and design lapse was the use of Rusnak's spreadsheet to feed exchange rates from Reuters to the bank's system. The treasury operations department allowed Rusnak to have the only feed from Reuters for exchange rates. The operations department designed an information system that included an employee's personal computer. This is a serious breach of good system design practices. It was a security hole. Rusnak was able to insert himself into the bank's information system and change data.

ACCOUNTING PRACTICES

The lack of audits and inadequacy of audits, the failure to review profit and loss, the practices of not confirming trades, not independently confirming exchange rates and not checking VaR independently with independent data allowed Rusnak to get away with fraud. Many of the techniques that Rusnak used were in direct violation of the Guidelines for Foreign Exchange Trading. In particular, trades are expressly recommended to be confirmed as soon as possible.47 The practices that Rusnak used would not have been effective if regular audits were conducted, if data used for calculations was independently verified and if trade confirmations had been made. Also, if the risk management departments had strong executive backing, they could have been much more effective.

CONCLUSION

John Rusnak did act alone. He had no direct accomplices. However, there were many indirect accomplices. All those who did not report what they saw, allowed him to talk them out of doing their jobs, and trusted the status quo rather than ask questions to get to the truth assisted Rusnak. Allfirst experienced problems that many corporations have. They had organizational political conditions influencing decisions. The fact that Allfirst was owned by a foreign company introduced some additional complexity in politics. Decision making in corporations can be based on budgets at the expense of other important considerations. Some decisions are made by looking at short term cost, rather than long term considerations. Employees don't always follow the standards set by their company. And supervisors can be too busy to enforce the standards. How a corporation and the people in it address these challenges is the differentiator between failure and long term success.

Albert Einstein is quoted as saying “insanity is doing the same thing and expecting different results.” Rusnak was a person who got himself in trouble and then kept using the same methods to get himself out of trouble. He kept placing the same types of bets hoping for the same outcome: that the dollar would fall against the yen. He had full responsibility for his actions. The corporation had responsibility also. AIB and Allfirst allowed an environment where he could commit his fraudulent actions.

In the case of AIB and Allfirst, the suggestions of the Ludwig Report were implemented. The company hopefully learned quite a bit from the analysis and suggestions in the report.

NOTES

1. Brian Coyle, Foreign Exchange Markets (Chicago: Glenlake Publishing Company, Ltd, 2000) 3.

2. J. Monville Harris Jr. PhD, International Finance (Barron's Educational Series 1992) 9.

3. Interbank Foreign Exchange Rates, table (WallStreet Journal) Apr. 16, 2003.

4. Andrew J. Kreiger, The Money Bazaar: Inside the Trillion-Dollar World of Currency Trading (New York: Times Books, 1992) 21–22.

5. Foreign Exchange Committee. The Federal Reserve Bank of NY, Guidelines for Foreign Exchange Trading Activities (New York: Foreign Exchange Committee, October, 2002) 3.

6. Brian Coyle, Foreign Exchange Markets 16.

7. Brian Coyle, Foreign Exchange Markets 63.

8. Brian Coyle, Currency Futures 15, 25.

9. Brian Coyle, Foreign Exchange Markets 101–102.

10. Siobhán Creaton and Conor O'Clery, Panic at the Bank: How John Rusnak lost AIB $691,000,000 (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 2002) 69, 73.

11. Promontory Financial Group and Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen, & Katz. Report to the Boards of Directors of Allied Irish Banks, P.L.C., Allfirst Financial Inc., and Allfirst Bank concerning Currency Trading Losses. (Mar. 12, 2002) 7, 9–10.

12. Robert Soloman, Money on the Move – The Revolution in International Finance since 1980 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999) 134.

13. http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/H10/hist/dat96_ja.txt

14. Siobhán Creaton and Conor O'Clery, 78.

15. Promontory Financial Group, 10.

16. Siobhán Creaton and Conor O'Clery, 78.

17. Jonathan Fuerbringer, “Bank Report says Trader Had Bold Plot.”, New York Times 15 Mar. 2002, C9.

18. Siobhán Creaton and Conor O'Clery, 77, 78.

19. Promontory Financial Group, 15.

20. Siobhán Creaton and Conor O'Clery, 83.

21. Promontory Financial Group, 12.

22. Siobhán Creaton and Conor O'Clery, 84.

23. Jonathan Fuerbringer, “Arcane Rollover System Let Trader Hide Losses,” C-3.

24. Foreign Exchange Committee, 7.

25. Jonathan Fuerbringer, “Arcane Rollover System Let Trader Hide Losses,” C-3.

26. Siobhán Creaton and Conor O'Clery, 86, 87, 102.

27. Promontory Financial Group, 16.

28. Thomas P. Edmonds, ed. and Francis M. McNair, Edward E. Milam, Philip R. Olds, Cindy D. Edmonds, Nancy W. Schneider, Claire N. Sawyer. Fundamental Finance Accounting Concepts. (McGraw Hill 2003) 61.

29. Siobhán Creaton and Conor O'Clery, 97–99.

30. Jonathan Fuerbringer, “Former Trader indicted on Bank Fraud Charges” New York Times 6 June, 2002, C-5.

31. Siobhán Creaton and Conor O'Clery, 90–91.

32. Siobhán Creaton and Conor O'Clery, 108.

33. Siobhán Creaton and Conor O'Clery, 107–109.

34. Jonathan Fuerbringer, “Former Trader Indicted on Bank Fraud charges”, C-5.

35. Jonathan Fuerbringer, “Ex-Currency Trader Sentenced to Seven and a half years,” New York Times 18 Jan. 2003, C-14.

36. Siobhán Creaton and Conor O'Clery, 15.

37. Siobhán Creaton and Conor O'Clery, 24.

38. AIBgroup, Annual Reports and Accounts 2001 for the Year ended 31 December, 2001 (Dublin: 2002) 4, 13.

39. Promontory Financial Group, 15–19.

40. Siobhán Creaton and Conor O'Clery, 91.

41. Promontory Financial Group, 19–20.

42. Promontory Financial Group, 22–25.

43. Foreign Exchange Committee, 7.

44. Siobhán Creaton and Conor O'Clery, 93.

45. Promontory Financial Group, 31–38.

46. Siobhán Creaton and Conor O'Clery, 80.

47. Foreign Exchange Committee, 24.

REFERENCES

AIBgroup. Annual Reports and Accounts 2001 for the Year ended 31 December, 2001 Dublin. http://www.aib.ie.

Coyle, Brian. Currency Futures. Chicago: Glenlake Publishing Company, Ltd, 2000.

Coyle, Brian. Foreign Exchange Markets. Chicago: Glenlake Publishing Company, Ltd, 2000.

Coyle, Brian. Hedging Currency Exposures. Chicago: Glenlake Publishing Company, Ltd, 2000.

Creaton, Siobhán and O'Clery, Conor. Panic at the Bank: How John Rusnak lost AIB $691,000,000. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 2002.

Edmonds, Thomas P., ed., Francis M. McNair, Edward E. Milam, Philip R. Olds, Cindy D. Edmonds, Nancy W. Schneider, Claire N. Sawyer. Fundamental Finance Accounting Concepts. McGraw Hill 2003.

“Ex-Currency Trader Sentenced to Seven and a half years” New York Times 18 Jan. 2003, C-14.

Foreign Exchange Committee. The Federal Reserve Bank of NY. Guidelines for Foreign Exchange Trading Activities. October, 2002 http://www.newyorkfed.org/fxc.

Fuerbringer, Jonathan. “Arcane Rollover System Let Trader Hide Losses” New York Times 19 Feb. 2002, C-3.

Fuerbringer, Jonathan. “Bank Report says Trader Had Bold Plot.” New York Times 15 Mar. 2002, C9.

Fuerbringer, Jonathan. “Former Trader Indicted on Bank Fraud Charges” New York Times 6 June, 2002, C-5.

Harris, J. Monville, Jr. PhD. International Finance. Barron's Educational Series. 1992.

Interbank Foreign Exchange Rates. Table. Wall Street Journal, Apr. 16, 2003.

Kreiger, Andrew J. The Money Bazaar: Inside the Trillion-Dollar World of Currency Trading with Edward Claflin. New York: Times Books, 1992.

Promontory Financial Group and Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen, & Katz. Report to the Boards of Directors of Allied Irish Banks, P.L.C., Allfirst Financial Inc., and Allfirst Bank concerning Currency Trading Losses. Mar. 12, 2002 http://www.aib.ie.

Soloman, Robert. Money on the Move – The Revolution in International Finance since 1980. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999.

Sutton, William. Trading in Currency Options. New York: New York Institute of Finance, 1988.

http://www.ft.com Financial Times. London.

Reproduced by permission from Sharon Burke, “Currency Exchange Trading and Rogue Trader John Rusnak”, edited by Klaus Volpert, Concept, Vol. 25 (Spring 2004), Villanova University. Retrieved on 10th October 2005 from http://www.publications.villanova.edu/concept/2004.html. Edited by Martin Upton.