CASE STUDY 9

Journey to Junk

Jenny Wiggins

Owning General Motors' bonds in recent years must have seemed to some like being a passenger in a car speeding down a mountain road. From a position close to the peak of creditworthiness, the largest US carmaker has seen its credit rating career towards the precipice that separates the best-rated, investment grade companies from their junk-rated counterparts.

Now, the edge of the cliff appears to some to be drawing closer. Over the past few weeks, bonds issued by GM and General Motors Acceptance Corp – its finance subsidiary, which issues the vast bulk of the car company's overall debt – have fallen sharply in value. Investors have become increasingly convinced that Standard & Poor's, one of the three leading credit ratings agencies, is moving closer to lowering GM's ratings to junk.

Such a downgrade would be a striking confirmation of the problems at a company whose fortunes have traditionally been regarded by investors as closely intertwined with those of the wider US economy. But just as important would be the potential reaction in US debt markets. If GM loses its investment-grade rating some holders of its bonds will be forced to sell them – and it is the extent of any market upheaval this could cause that has been unnerving many.

In 2002, the downgrade to junk of more than $30bn of debt issued by WorldCom, the telecommunications company that went bankrupt, was one of the factors contributing to a sharp widening in yield spreads. With GM and GMAC having a combined $51bn of debt tracked by Lehman's Credit Index, some market observers are worried that the downgrade of billions of dollars of their debt to junk could cause similar havoc.

“It's unlikely that the market could absorb such a large issuer,” says Craig Hutson, analyst at Gimme Credit, an independent bond research firm. “If it does happen, it would be a monumental event.” Freshly fallen GM and GMAC debt would comprise almost 10 per cent of the US junk bond market, according to analysts at UBS.

Worries would be exacerbated if Ford – another US carmaker whose bonds have also been trading at levels more associated with junk – also eventually loses its investment grade credit rating, though this is not seen as imminent. Like GM, it has a rating one notch above junk. “It was like Chinese water torture,” says a portfolio manager at one large bond fund, describing the state of the bond markets in 2002. “The fear is that $95bn of debt [GM and Ford] will go through this.”

There is a contrary view, however. Other market observers believe that a downgrade of GM has been so well telegraphed that if and when it finally happens, the markets will manage it well. The belief is based on a series of adjustments being made by participants – agencies, investors and others – to make sure that the impact will be minimised.

If GM does take the plunge to junk, in other words, most market players may yet emerge unscathed.

Fears that a downgrade is on the way increased this month after GM reported poor February sales figures and announced production cutbacks, which will hurt its earnings. Already in January S&P had warned that it was becoming increasingly worried about GM's ability to improve its competitiveness. It hinted it was considering changing its “stable” outlook on GM's and GMAC's ratings to “negative”.

In the early 1990s GM held a relatively high AA-credit rating from S&P. But as the company's fortunes have waned, with increasing competition from foreign manufacturers and rising pension costs, ratings for it and GMAC have drifted steadily lower. Today, GM and GMAC are assigned a BBB-rating from S&P – the lowest possible rating they can hold and still be considered investment grade.

Moody's, S&P's main rival, also warned in February that GM faced “increasing challenges” and changed its outlook to negative for both GM and GMAC. However Moody's ratings are higher than S&P's, at two and three notches above junk status for GM and GMAC respectively. Fitch, the third-largest credit rating agency, also has GM and GMAC two notches above junk. That means S&P's movements are the ones being most closely watched.

The line that separates investment-grade companies from non-investment grade companies is more than just an arbitrary difference of letters (BBB-versus BB+, in the case of S&P). The opinions of ratings agencies are enshrined in federal securities laws, limiting the kinds of debt that investment funds can buy. When an agency drops a rating on a company's corporate bonds from investment-grade status some investors have to get rid of the bonds, sparking forced selling.

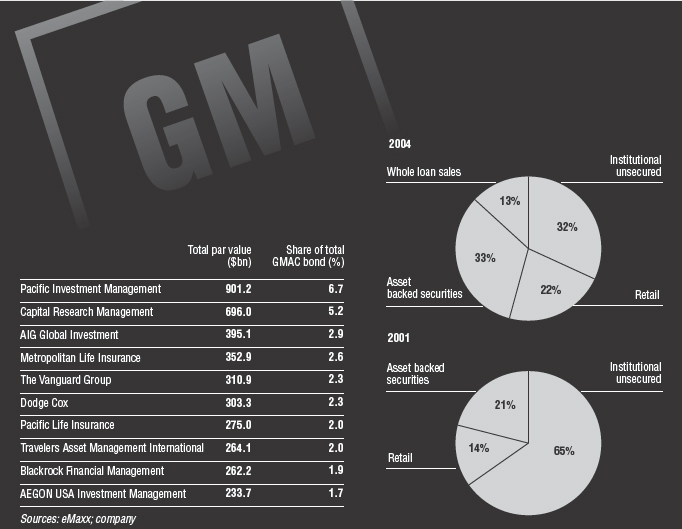

GMAC's bonds are widely held by big US and European investment firms including Pimco, Fidelity and Allianz Dresdner Asset Management. Pimco is the largest US holder of GMAC bonds with a face value of some $901m, according to Lipper, a company that provides research on equity and bond funds.

While some junk bond fund managers may want to buy GM's debt if it is downgraded, they are under no obligation to do so. So-called “fallen angels” – companies that lose their investment-grade ratings – are typically unpopular with junk bond managers because their debt issues generally have weaker covenants (financial arrangements that protect the lender's interests) than bonds originally issued with junk ratings. If there are no immediate buyers for the debt the price of GM's bonds could fall sharply until it hits a level at which it becomes attractive to distressed debt investors.

“Even though [a downgrade] is anticipated, you could have a somewhat unruly market in GM paper,” says Martin Fridson, chief executive of independent high-yield research firm Fridson-Vision.

Credit rating agencies move slowly, however, and this has advantages for both GM and investors: it allows them to prepare for a possible ratings downgrade.

Some credit analysts compare the rating agencies' tactics to the hints that the US Federal Reserve drops before it changes its closely watched Federal funds interest rate. “It's like the Fed funds,” says Kingman Penniman, president of KDP Investment Advisors, an independent corporate bond research firm. “They tell you everything that happens before it happens so when it happens there's a rally.” Mr Penniman is among those who believe that a downgrade of GM would not be a tremendous financial event for the market.

One of the beneficiaries of the agencies' slow and steady approach has been GM itself. Because it is GMAC's unsecured debt that is at risk of a downgrade to junk, the company has been cutting back the amount of unsecured debt it issues while increasing the amount of asset-backed securities and retail bonds it sells. “We have fundamentally changed the way we approach the credit markets,” says Eric Feldstein, chairman of GMAC.

Some 65 per cent of GMAC's funding was sourced from the unsecured market in 2001, compared with only 32 per cent in 2004. About 33 per cent of GMAC's funding last year came from selling asset-backed securities, while 22 per cent was achieved through selling bonds to retail investors (see Figure C9.2).

Combined, GM's and GMAC's total debt outstanding at the end of 2004 was about $301bn, including some $268.7bn issued by GMAC.

GMAC is also considering insulating parts of its business from the main company so that, even if GMAC's rating falls, its profitable business segments will retain a higher rating. Mr Feldstein says GMAC may restructure its residential mortgage operations – one of the key businesses within its finance operations, accounting for $1.1bn out of an overall $2.9bn in profits last year – into a new holding company that would have its own credit rating.

GMAC says it has already received assurances from rating agencies that the new company would command a higher rating than GM or GMAC.

Rating agencies say they are frequently contacted by investment bankers trying to find ways to restructure GMAC in order to secure a higher overall rating for the business.

Scott Sprinzen, motor analyst at S&P in charge of GM's credit rating, said the agency was often shown ideas. “If it ever came to pass that we look at lowering the credit rating you can be sure that will get a lot of attention,” he says.

One possibility raised by financial analysts is a mirror of the structure used by Italy's Fiat Auto, which is rated as junk. It sold a controlling stake in Fidis, its finance arm, to a group of banks – thus securing Fidis a higher rating. But GM has dismissed such ideas and analysts admit that relinquishing control is a last resort for the carmaker, as the finance arm provides essential support to its network of dealerships.

Figure C9.1 Top 10 holders of GMAC bonds

Figure C9.2 GMAC US funding mix

GM has reduced its reliance on expensive unsecured debt by utilising lower-cost secured funding

Meanwhile, investors also have been preparing for a downgrade by getting rid of carmakers' bonds and buying the debt of other investment-grade companies – one of the factors contributing to record tight credit spreads as demand for non-motor industry paper has outstripped supply. In February, investment grade credit spreads hit their tightest levels since May 1998, according to Lehman.

“People have pared down auto exposure dramatically and have reallocated to other sectors,” says Mary Rooney, head of credit strategy at Merrill Lynch, adding that most investors appear to be well positioned for a potential downgrade of the carmakers.

In the junk bond market, some investors have been preparing for a possible influx of carmakers' debt by starting to track so-called “constrained” indices, which limit the weighting of any one debt issuer. These indices prevent investors from being too exposed to a single issuer – such as WorldCom, which composed nearly 4 per cent of Merrill Lynch's global high-yield index before its default in 2002. Merrill subsequently introduced a constrained US highyield index, putting a 2 per cent cap on any one name in the index.

Other market participants have also been taking action to minimise potential market disruption. One is Lehman Brothers, whose indices are the most widely tracked in the bond markets, with the vast majority of bond fund managers benchmarking their performance against them.

Traditionally, Lehman has used only ratings from Moody's and S&P, meaning that if one of these two agencies downgraded a company to junk, it would automatically fall out of Lehman's investment-grade index. But in January Lehman decided to start including ratings from Fitch.

That means that if S&P does strip GM of its investment grade rating but other agencies do not, GM will stay in the index and fund managers will not necessarily be forced to sell. Lehman's move follows similar action by Merrill Lynch, which included Fitch in its bond indices last year.

Lehman's change relieved fund managers, encouraging some investors to buy back GM bonds amid expectations that GM will stay in the investment grade index for some time to come. “Everyone breathed a sigh of relief,” says Stephen Peacher, chief investment officer, corporates and emerging markets, at Putnam Investments.

It remains to be seen whether the careful approach taken by the ratings agencies as well as the steps taken by investors and the investment banks will allow a downgrade of GM debt to be absorbed by the markets without disruption. But one other factor that would support a smooth transition to junk status is that GM's problems are considered company-specific.

In 2002, revelations of fraud and accounting misdemeanours at many US companies created enormous volatility in the corporate bond market because investors did not know which company would be next to succumb to scandal. But GM's problems, which are related to its cost structure and loss of market share, are not considered leading indicators of potential problems at companies in other sectors.

“GM's problems are not viewed as systemic risk,” says Ms Rooney at Merrill Lynch. “In 2002, there were systemic issues related to corporate governance and fraud, and over-leveraged balance sheets.”

This would mean that, even if investors sold GM's bonds heavily following a downgrade, contagion selling throughout the bond markets would not be likely.

Some market observers liken the demise of GM's creditworthiness to that of AT&T, which once held a top-notch AAA credit rating and was considered the pricing benchmark for the corporate bond markets. AT&T, the telecoms company that had some $10bn of corporate debt outstanding, slipped to junk status last year but bond markets barely stirred.

“AT&T was a pricing benchmark in the bond market for a long time,” says Mr Fridson, “But there was not much in the way of repercussions.”

That gives some hope to those who believe that, even if GM is on a journey to junk status, the heartstopping ride may yet get most passengers home safely.

Reproduced by permission from the Financial Times (10 March 2005). © The Financial Times Ltd.