22

Controversy Incorporated

David Cogman and Jeremy M. Oppenheim

Milton Friedman once famously said that “the business of business is business.”1 Today, however, the search for growth increasingly takes companies into controversial areas in which the rules of the game can't be stated so neatly. Companies developing new high-growth opportunities in fields from technology to education to economic development must often navigate highly public ethical and social concerns and overcome restraints far more subtle than those encountered in standard business practice or law. Increasing numbers of large corporations thus find themselves caught between two seemingly contradictory goals: satisfying the investor's expectations for progressive earnings growth and the consumer's growing demand for social responsibility.

Companies have become more socially responsible primarily because apparent irresponsibility can carry a high price (see Box 22.1). Although many companies now spend significant sums of money to comply with their own codes of ethical conduct, most view these expenditures only as an essential cost of doing business, not as an investment that will provide a return. For some of these companies, however, this spending may well be a source of growth, since many of today's most exciting opportunities lie in controversial areas such as gene therapy, the private provision of pensions, and products and services targeted at low-income consumers in poor countries. These opportunities are large and mostly untapped, and many companies want to open them up. But people are often suspicious of any private-sector interest in contentious areas of this kind, and public debate rages over how they should be developed, if at all.

Corporations have to be recognized as socially responsible simply to gain access to these debates. To influence the outcome, however, it will be necessary to do more than just check boxes on a corporate-responsibility scorecard; unless companies can understand, engage with, and respond to the interests of all parties that have an interest in a contentious business opportunity, they are unlikely to win a society's permission to explore it. Without that permission, they will never convert the opportunity into a sustainable and profitable market.

Box 22.1 A force to be reckoned with

Two decades ago, the activists who demanded that companies practice a higher standard of social responsibility were scattered throughout a disparate collection of organizations, each focused, for the most part, on a single issue. No longer. Today's lobbyists are a well-coordinated and effective force. And they have teeth. In a recent poll of about 25,000 people in 23 countries, 60 percent of the respondents said they judged a company on its social record, 40 percent took a negative view of companies they felt were not socially responsible, and 90 percent wanted companies to focus on more than just profitability.1

Meanwhile, the activist lobby has learned how to form unlikely alliances across the political spectrum – with people ranging from conservative protectionists to Left-wing trade unionists – and to mobilize public opinion on emotional issues through the skillful use of the mass media. Many multinational companies have learned from experience how effective these tactics can be. In particular, extractive industries such as petroleum have come under relentless pressure from environmental activists: Shell lost considerable market share in Germany in 1995 after activists persuaded consumers that its proposed disposal of the Brent Spar oil platform, in the North Sea, would harm the environment. Even though the UK government and independent scientists had endorsed the company's proposal as the one that would cause the least damage, motorists boycotted Shell's service stations, and some were vandalized by activists.

These days, moreover, it isn't just consumers who are clamoring for change; shareholders too are making their voices heard. Prominent pension funds have begun to question companies on social issues, and socially responsible investing, though still a relatively small-scale phenomenon, is growing rapidly. In the United States, the assets of what are called ethical funds grew from $682 billion in 1995 to $2.16 trillion in 1999, and they now make up approximately 13 percent of investments under management in the United States, which is up from 9 percent in 1997. It is no wonder that so many corporations are beginning to take their social responsibilities seriously.

- From the 1999 Millennium Poll, conducted by Environics, the Prince of Wales International Business Leaders Forum, and The Conference Board.

CONTENTIOUS ATTRACTIONS

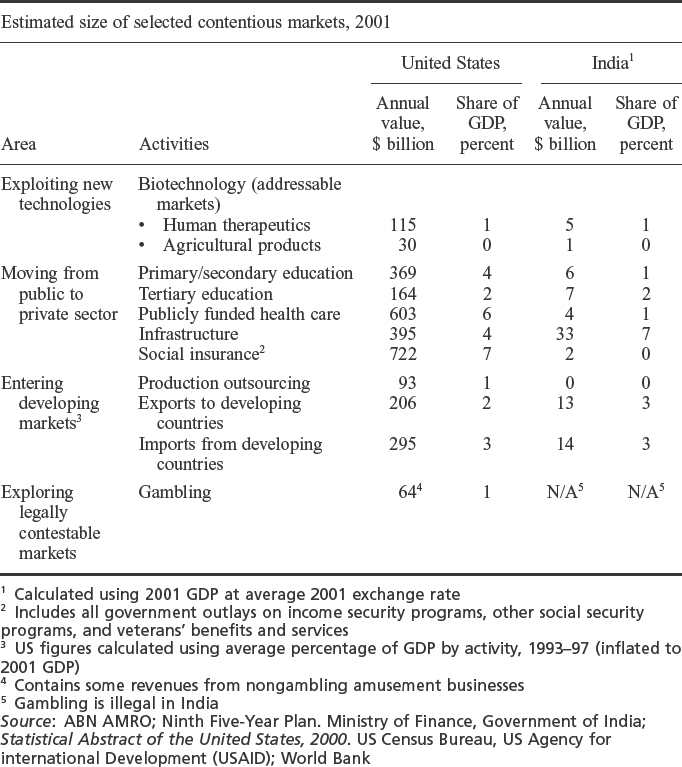

Ethical considerations might appear to clash with emerging business opportunities primarily in four areas: the exploitation of new technologies, the movement of activities from the public to the private sector, entry into the world's developing markets, and the exploration of such legally contestable markets as gambling (Table 22.1).

Table 22.1 Where principles and profits clash

Exploiting New Technologies

In recent decades, promising new developments, notably in biotechnology and information technology, have frequently been accompanied by debates about ethics. Take biotechnology: R&D into human therapies based on it is growing almost twice as quickly as R&D into conventional pharmaceuticals – and leading to 40 percent of all new products. By the end of this decade, biotechnology is expected to generate revenues of around $34 billion (equivalent to 15 percent of today's total drug market) from health care and $25 billion from agrochemicals. And though existing biotechnology applications can compete for only 2 percent of today's $1.2 trillion market in industrial chemicals, this proportion is projected to rise to almost a third by the end of the decade, when the total market will be worth an estimated $1.6 trillion.

Yet there is concern about the moral legitimacy of the genetic research on which biotechnology depends. Consider the case of deCODE Genetics, a company in Iceland that has used a genealogical database of the country's population – one of the world's most genetically homogeneous – to conduct research into the inherited causes of common diseases. So far, the company has found links between at least 40 of them and 350 genes. The legislation that gave deCODE access to this data required Icelanders to opt out if they didn't want their records examined. Critics of the study claimed that this legislation violated the human rights of the Icelanders, especially since it didn't require the company to tell participants exactly how the data would be used. Ignoring such concerns may not only lead to further argument but also limit the ability of biotech companies to carry out valuable and much-needed research.

Moving from the Public to the Private Sector

Governments the world over increasingly use private-sector companies to provide public services such as education, health care, pensions, and transport. While this approach may improve efficiency and raise standards of service, it also generates criticism of the profits that private providers can earn, particularly for services, such as welfare benefits and housing, that affect the poorer segments of society.

Public education in the United States provides an example. The country spends more than $350 billion of public funds on primary and secondary education, which is widely thought to have fallen behind public education in other developed countries. Privatizing the provision of education is a possible solution. At present, only 4 percent of the spending goes to schools run for profit by private companies, but that proportion is expected to grow by 13 percent a year. At the end of the present decade, around 10 percent of all primary and secondary schools will probably be under for-profit management, suggesting a market worth almost $80 billion.

Nonetheless, the battle for privatized education run by companies seeking to make a profit is far from won. Business executives attempting to enter the debate – such as venture capitalist John Doerr and the convicted financier-turned-philanthropist Michael Milken – have met with suspicion and, often, outright hostility. Companies operating in this field face a continual battle to prove to skeptical teachers, parents, and administrators that a for-profit company can and will act in the best interest of students. This skepticism won't go away overnight.

Entering Developing Markets

Developing countries offer attractive opportunities both as markets and as sources of raw materials and productive capacity. But interest groups frequently criticize corporations active in these regions for failing to meet the environmental, labor, competitive, and marketing standards required of them at home.

Take health care in India, which illustrates both the scale of the opportunities in the emerging world and the ethical quandaries that accompany them. India's population will surpass China's in the near future. Even now, India is a popular location for the manufacture of drugs used in developed markets, but the country itself has health care expenditures of only $23 a head, of which $7 goes to drugs. The United States, the members of the European Union, and Japan spend, on average, more than 100 times that amount on health care per capita, and 50 times more on drugs.

The common causes of death in India – such as infection and perinatal problems – can be treated easily and cheaply. But most people there are so poor that it is difficult for companies to ask them to pay for medical help without seeming exploitative. Since 1991, the World Bank has supported projects in six Indian states to improve access to better health care, especially for the poor, in part by helping state-run health care providers outsource more of their services to the private sector. But this approach has attracted criticism from local activists opposed to the idea that local people should have to pay anything at all for health care.2

Exploring Legally Contestable Markets

Social norms define what each society considers legal, but they can change quickly: activities that once were against the law – such as euthanasia and the possession of cannabis (marijuana) – are now accepted in several European states. Black markets in illegal activities are often sizable, so sudden changes in the law can create substantial legitimate markets overnight. A black market in human trafficking, for example, has been created by tough immigration restrictions in Europe, but as its need for labor increases, they may be relaxed, thus opening up an opportunity for legitimate organizations seeking to place human resources.

Similarly, gambling, viewed in some times and places as a source of corruption, is increasingly seen as a legitimate form of entertainment; indeed, in several unlikely localities, including conservative states in the southern United States, it has proved to be an effective source of jobs and tax revenue. As gambling has become more respectable, large corporations, including several household names, have entered the business. During the 1990s, the industry more than doubled in size, and it is currently worth more than $60 billion.

EARNING THE RIGHT TO OPERATE PROFITABLY

Not all companies will want to commercialize contentious activities. But those that do need, first, to persuade everyone involved that a private company has the moral right to undertake the activity in question and, second, to establish a profit norm acceptable to all stakeholders, including investors. Winning both battles can be difficult, and companies will have to adopt different tactics for each activity and geographical market. Yet some common principles can help those companies engage sensitively and proactively in such debates.

Take a Long-Term View of Market Design

Economic theory declares that a well-functioning market respects the property rights of its participants, matches consumers with producers at efficient prices, minimizes transaction costs, and ensures that contracts are enforced. In most private-sector markets – for instance, those for cement and crude oil – well-established laws, regulations, and practices ensure these conditions. But in contentious markets, such as the one for gene therapy, some or all of this infrastructure doesn't exist, so it must be developed by participants and regulators.3

Private companies entering these markets therefore need to decide how they should be structured. How will value be created? How will it be shared? How will risks be allocated? What regulatory or contractual rules must be put in place? Companies may naturally be tempted to lobby for a structure – opaque, with limited price discovery, high barriers to entry, and an inefficient allocation of risk – that favors their interests over those of other participants. Would that approach serve a company's best long-term interests? Probably not; over time, its inherent unfairness would most likely prompt governments and activists to intervene. Greedy participants may risk losing markets altogether.

Consider the contrast between the privatized markets for energy and rail transport in the United Kingdom. In the decade following the privatization of electricity supply, a substantial fall in the unit cost of energy benefited both consumers and producers. In part, this achievement was the result of a thoughtful market design, which separated supply and distribution through a pooling system, and of a strong regulatory framework. Together, these arrangements managed supply and demand efficiently over the medium term.

Compare that positive experience with the fate of the United Kingdom's privatized rail industry, in which relationships among stakeholders were structured poorly. The result was a public outcry over the declining standard of service and a widespread perception in the mass media that some of the new rail enterprises were extracting “excessive” profits. Safety problems and cost overruns attracted a storm of negative publicity; amid battles with regulators and politicians, the infrastructure company, Railtrack, went into bankruptcy and was returned to government control. Had the market structure been more carefully designed at the outset, the cost of Railtrack's collapse might have been avoided, and British consumers might now be enjoying a higher standard of rail travel.

Learn to Work With – Not Around – Stakeholders

To propose an acceptable structure for any market, companies must understand the needs of its other participants, some of whom may distrust the private sector profoundly. In these circumstances, companies often try to neutralize their opponents with gifts and grand gestures, which can appear to be cynical and often backfire. The winning way may be counterintuitive: view the opposition not as a threat but as a source of information about the other market participants' needs and concerns. With that information in hand, companies can develop business models that address them.

One example is Cargill's initial entry into the market for sunflower seeds in India. Starting in the early 1990s, this activity generated bitter political opposition, and Cargill offices in that country were set on fire twice. The company's response was to teach Indian farmers how to improve their crop yields. As a result, the productivity of the local farmers increased by more than 50 percent. Once Cargill had provided them with a palpable economic benefit, they understood that the company aspired to be their partner rather than their exploiter.4

This collaborative strategy stands in stark contrast to Monsanto's effort to create markets for genetically modified seeds. The company was bitterly opposed by farmers in developing countries who feared becoming dependent on a single supplier of expensive seed. Instead of accommodating these concerns, Monsanto responded with an effort to publicize scientific evidence about the benefits of genetically modified seeds, but few of the farmers believed that the scientists supporting the company's claims were truly independent. Arguably, Monsanto lost the opportunity by pressing its claim too hard, too soon. Buffeted by a steady backlash in developing and developed markets alike, the company lost almost half of its market capitalization in the year to September 1999, and a few months later it was acquired.

Understand Your Social Assets

If large numbers of people are convinced that a company's core operations harm society, changing that negative perception by spending more money on corporate-responsibility programs can be an uphill struggle. However, many companies – even those with flawed reputations – already contribute a great deal to society through their day-to-day activities; they just don't get any credit. Identifying and publicizing these inherent social assets could help such companies build trust among stakeholders.

Take McDonald's. Although the company makes large, well-publicized social investments in fields as diverse as animal welfare, conservation, education, and health care, it is still, to its critics, the archetype of global corporate exploitation. Yet McDonald's is also a company that introduces many young people to new skills and gives them the first job of their careers. It could claim that as one of the world's largest employers of unskilled youth, it contributes enormous social value just by doing business as usual. If this value were more widely appreciated, it might even help McDonald's enter markets more controversial than fast food.

Other companies also have largely untapped social assets. Although (or perhaps because) the oil majors are the number-one enemy of environmental groups such as Greenpeace, these companies now have unrivaled expertise in minimizing the ecological impact of industrial operations. This asset is evidence of responsible commerce that can also help a company decide which markets to enter. Opponents of moves to legalize cannabis, for example, fear that the tobacco giants would ruthlessly exploit the opportunity to sell it over the counter. This may be a battle the tobacco companies can never win, however. A more likely candidate to distribute the drug, if and when it becomes legal, could be suppliers of over-the-counter pharmaceuticals, whose business already depends on a guaranteed commitment to responsible health care.

Rethink Leadership and Governance

Forward-looking companies, sensitive to the new ground rules of controversial business areas, are opening up to – rather than fighting – their opponents. Corporations, such as those in oil and pharmaceuticals, that have years of experience collaborating with governments have a head start in training employees to work in contentious areas: these companies also regularly expose managers to a range of critical opinion by assigning them to work with nongovernmental organizations and by taking part in conferences.

In some cases, such companies even seek out critics to learn from them: the leading UK environmental activist Jonathon Porritt, for instance, speaks at and advises on training programs for BP executives. Indeed, such relationships can even work in both directions, for BP's chief executive serves on the board of Conservation International, a global conservation group. This kind of “cross-pollination” not only gives companies insights into the concerns of the not-for-profit sector but also gives not-for-profits accurate information about the companies they deal with. The free exchange of information makes the two sides better able to reach acceptable compromises on questions such as the way the oil majors might exploit reserves in virgin territory.

Finally, to involve consumers and communities, ventures in contentious markets usually require governance structures independent of the corporate parents.5 Bolder companies may even experiment with new forms of governance that try to combine the strengths of the corporation with the social awareness of the not-for-profits – an approach that has already been used by a growing number of community-development financial institutions providing capital to businesses in disadvantaged areas that conventional banks can't or won't serve.6 One example is Bridges Community Ventures, a UK venture fund founded by the venture capital firms Apax and 3i and by entrepreneur Tom Singh and financed by leading private-sector investors and the UK government. Bridges is a for-profit entity but invests solely in underdeveloped areas in England to stimulate growth and create jobs.

Companies willing and able to address the social concerns surrounding contentious markets will find that, in many cases, the rewards are more than worthwhile. Moreover, the participation of companies that know how to tackle such issues sensitively and effectively should improve the chances of addressing some of the world's most intractable problems. And it is increasingly difficult to imagine how such complex, large-scale tasks can be taken on without the private sector's involvement.

NOTES

1. Milton Friedman, “The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits,” New York Times Magazine, September 13, 1970.

2. See the World Wide Web sites of Global Action, Corpwatch, and the World Bank.

3. For an analysis of the problems of market design, see John McMillan, Reinventing the Bazaar: The Natural History of Markets, New York: Norton, 2002.

4. For an account of these developments, see Stuart L. Hart and C. K. Prahalad, Strategies for the Bottom of the Pyramid: Creating Sustainable Development, July 2000.

5. See Rajat Dhawan, Chris Dorian, Rajat Gupta, and Sasi K. Sunkara, “Connecting the unconnected,” The McKinsey Quarterly, 2001 Number 4 special edition: Emerging markets, pp. 61–70; and Amie Batson and Matthias M. Bekier, “Vaccines where they're needed,” The McKinsey Quarterly, 2001 Number 4 special edition: Emerging markets, pp. 103–12.

6. For more details, see the UK Social Investment Forum report Community Development Finance Institutions: A New Financial Instrument for Social, Economic, and Physical Renewal, February 2002.

Reproduced from The McKinsey Quarterly, 2002 Number 4. Copyright © 1992–2005 McKinsey & Company, Inc.