CASE STUDY 15

Corporate Governance Failures: To What Extent is Parmalat a Particularly Italian Case?

Andrea Melis

INTRODUCTION

The Parmalat situation started out as a fairly standard – although sizeable – accounting fraud. The Parmalat group, a world leader in the dairy food business, collapsed and entered bankruptcy protection in December 2003 after acknowledging massive holes in its financial statements. Billions of euros seem to have gone missing from the company's accounts. This dramatic collapse has led to the questioning of the soundness of accounting and financial reporting standards as well as of the Italian corporate governance system.

Some of the Anglophone business media (e.g. Heller, 2003; Mulligan and Munchau, 2003; Lyman, 2004) have been labelling the Parmalat case as a particularly Italian scandal, suggesting that a case such as Parmalat is country-specific and more likely to happen in Italy than elsewhere. This is not surprising as Italy is also widely represented as a bad example in the existing international academic literature on corporate governance (e.g. La Porta et al., 1997; Macey, 1998; Johnson et al., 2000). It has been argued that its reputation for corporate governance is “sufficiently bad” to let international authors on this topic “feel confident in awarding bad marks without serious field research”. Institutions of Italian corporate governance have been “translated in black and white, and some have not been translated at all” (Stanghellini, 1999, p. 4).

The main purpose of this paper is to examine the Parmalat case in order to understand to what extent it may be considered a particularly Italian scandal, which might imply that international scholars and policy makers could disregard the corporate governance problems that emerged at Parmalat as country-specific, or whether it is a case that fits into a global corporate governance argument.

The main accounting and corporate governance issues related to the case will be examined and discussed. The paper will focus on the supply side of information (i.e. internal governance agents, senior management and external auditors). The role of the information demand-side agents (i.e. institutional and private investors, information analysers such as financial analysts and rating agencies, etc.) is out of the scope of the paper since those agents are not country-related factors. Legal aspects of the case will be not be discussed since prosecutors are still investigating these issues.

It has been argued (see Melis and Melis, 2004) that the Parmalat case is not due to a failure of generally accepted accounting principles. Although financial misreporting is the most evident issue, the Parmalat case is basically a false accounting story due to corporate governance failures.

Nevertheless, the question that it raises is how it was possible. Why did the corporate governance system not make senior managers accountable for their action and, if not prevent, stop their action well before the company's collapse?

Therefore, the main characteristics of Parmalat's corporate governance structure will be examined in order to understand why false accounting was possible and remained concealed for over a decade.

In the next sections the paper will investigate which monitoring mechanisms failed, and to what extent these failures are due to weaknesses specific to the Italian corporate governance system, or if in fact they fit into the global corporate governance issues. Hence the paper will compare and contrast the main characteristics of Parmalat's corporate governance system with the corporate governance system that prevails among Italian listed companies as well as with the recommendations of the Italian code of best practice, in terms of ownership, control and monitoring structures.

OWNERSHIP AND CONTROL STRUCTURES: PARMALAT VS ITALY

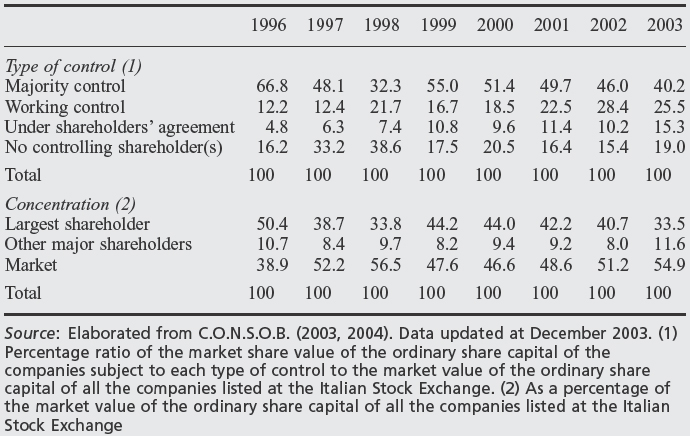

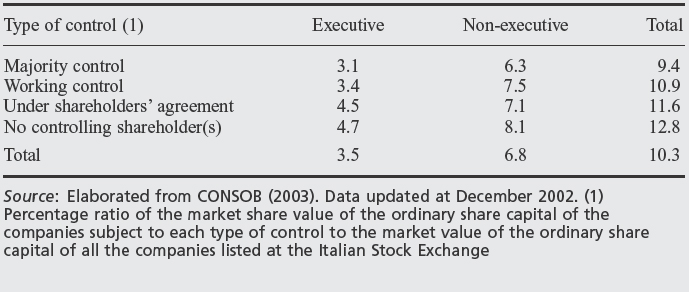

The ownership and control structure of Italian listed companies is characterised by a high level of concentration (see Table C15.1), and by the presence of a limited number of shareholders, linked by either family ties or agreements of a contractual nature (i.e. shareholders' agreements), who are willing and able to wield power over the corporation.

Table C15.1 Ownership and control structure of listed companies

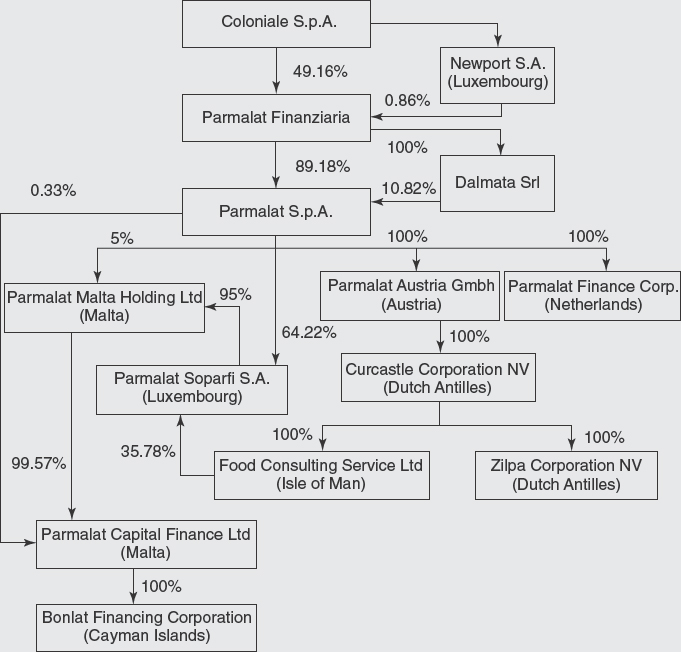

Parmalat was a complex group of companies controlled by a strong blockholder (the Tanzi family) through a pyramidal device.1 From this viewpoint, it seems a very Italian case. Despite ownership disclosure rules, the structure of the group is not easy to trace, especially at an international level. This is not unusual among large Italian groups (Melis, 1999), but it is also a common problem among continental European groups (Becht, 1997). In these groups a holding company controls (directly or indirectly) the majority of voting rights of the companies which belong to the group. Its ultimate control is held by a single entrepreneur, or a family (as in the Parmalat case), or a coalition.

In fact, Parmalat S.p.A. represented the core milk and dairy food business of the Parmalat group, and controlled 67 other companies directly (as at 31 December 2002), and many others indirectly (Parmalat S.p.A., 2002). It was an unlisted company controlled by Parmalat Finanziaria with 89.18 per cent of its voting share capital. The remaining 10.82 per cent of the shares were owned by Dalmata S.r.l., an unlisted financial company which was fully controlled by Parmalat Finanziaria.

Parmalat Finanziaria was listed on the Milan stock exchange market. Its main shareholder (as at 30 June 2003) was represented by Coloniale S.p.A., which owned 50.02 per cent of the company voting share capital: 49.16 per cent was held directly, while 0.86 per cent was controlled indirectly through the Luxembourg-based Newport S.A. Two institutional investors (Lansdowne Partners Limited Partnership and Hermes Focus Asset Management Europe Limited), which owned 2.06 per cent and 2.2 per cent respectively, were the major minority shareholders.

Coloniale S.p.A., the holding company of the group, was under the control of the Tanzi family, through some Luxembourg-based companies. Therefore, the Tanzi family was the ultimate shareholder controlling Parmalat Finanziaria and the whole Parmalat group.

A simplified structure of the group will be shown, displaying only the links that are more relevant to the purpose of the paper (see Figure C15.1).

Shleifer and Vishny (1986) argued that large shareholders have adequate incentives to exercise monitoring. Empirical evidence (e.g. Becht, 1997; Molteni, 1997; Melis, 1999) shows that the Italian prevailing control structure is characterised by the presence of an active shareholder (the block-holder) who is willing and able to monitor the senior management effectively.

This type of ownership and control structure allegedly reduces the classical agency problem between senior management and shareholders: senior managers who pursue their own self-interest at the expense of shareholders will be displaced by the controlling shareholder. Nevertheless, the agency problem is only shifted towards the relationship between different types of shareholders: the controlling shareholder and minority shareholders (La Porta et al., 2000; Melis, 1999, 2000). If the main corporate governance issue in the USA is “strong managers, weak owners” (Roe, 1994), the key corporate governance problem in Italy is about “weak managers, strong blockholders and unprotected minority shareholders” (Melis, 2000, p. 351).

Figure C15.1 Parmalat's ownership structure: a simplified version

Blockholders may use their power to pursue their interests at the expense of minority shareholders, by diverting corporate resources from the corporation to themselves, either legally or illegally (Johnson et al., 2000). This is what happened in the Parmalat case: Tanzi acknowledged to Italian authorities that Parmalat funnelled about Euro 500 million2 to companies owned by the Tanzi family, especially to Parmatour. The latter was not a subsidiary of Parmalat. It was an unlisted company owned by Nuova Holding, a Tanzi family investment company.

THE MONITORING STRUCTURE: WHEN THE MONITORED CONTROLS THE MONITORS

The monitoring structure in Italian listed companies is characterised by the presence of two key gatekeepers: the board of statutory auditors and the external auditing firm. While the former is a particularly Italian device, the latter is certainly a widespread gatekeeper around the world.

The Role of the Board of Statutory Auditors

Italian law required listed (and unlisted) companies to set up a board of statutory auditors.3 This board acts as the fundamental monitor inside the company. After the Draghi Reform (1998, Art. 149) its main tasks and responsibilities include:

- to check the compliance of acts and decisions of the board of directors with the law and the corporate bylaws and the observance of the socalled “principles of correct administration” by the executive directors and the board of directors;

- to review the adequacy of the corporate organisational structure for matters such as the internal control system, the administrative and accounting system as well as the reliability of the latter in correctly representing any company's transactions;

- to ensure that the instructions given by the company to its subsidiaries concerning the provision on all the information necessary to comply with the information requirements established by the law are adequate.

The Draghi Reform (1998, Art. 148) also requires corporate by-laws to provide the number of auditors (not less than three), the number of alternates (not less than two), the criteria and procedures for appointing the chairman of the board of statutory auditors and the limits on the accumulation of positions. Corporate by-laws shall also ensure that one (or two, when the board is composed of more than three auditors) of the members of the board of statutory auditors is appointed by the minority shareholders, so that the composition of the board reflects the will of all shareholders.

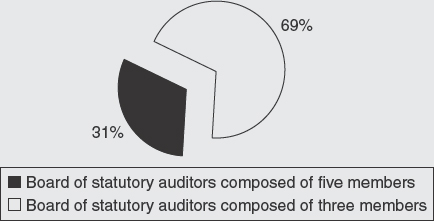

Parmalat Finanziaria's board of statutory auditors was composed of three members, i.e. the legal minimum requirement. This is not unusual among Italian listed companies. Consob (2002) reported that approx. 92 per cent of the boards of statutory auditors of listed companies were composed of three members. Even among the largest companies that are listed in the MIB304 (as Parmalat Finanziaria was from 1994 to 1999 and again from 2003), only approximately 30 per cent of the companies have set up a board of statutory auditors with more than three members. In such a case companies always choose a five-member board (see Figure C15.2).

As underlined in Melis (2004), the size of the board of statutory auditors has a direct influence over the level of protection on minority shareholders because some powers (e.g. the power to convene a shareholders' meeting because of a directors' decision) may be exercised only by at least two members of the board jointly. Only when the board of statutory auditors is composed of more than three members can minority shareholders appoint two statutory auditors.

Figure C15.2 Size of the board of statutory directors among Italian MIB30 listed companies

Source: Elaborated with data based on CONSOB database. Data updated at December 2003. One company listed on MIB30 has not set up a board of statutory auditors. Being based in the Netherlands it has chosen a two-tier board structure, with a supervisory council

The Parmalat Finanziaria board of statutory auditors never reported anything wrong in their reports, nor to courts or to CONSOB5 (Cardia, 2004). Nor did the statutory auditors at Parmalat S.p.A. or any of its subsidiaries. Even when, in December 2002, a minority shareholder (Hermes Focus Asset Management Europe Ltd) filed a claim (pursuant to clause 2408 of the Italian civil code) regarding, among other issues, related-parties transactions, the board of statutory auditors answered that “no irregularity was found either de facto or de jure”.

This seems to confirm the argument (see Melis, 2004) that in a corporate governance system characterised by the presence of a strong blockholder, like Parmalat (and most Italian companies), the board of statutory auditors seems to provide a legitimating device, rather than a substantive monitoring mechanism.

The inefficiency of the board of statutory auditors as a monitor has been attributed to (a) its lack of access to information related to shareholders' activities, and (b) its lack of independence from the controlling shareholders (for a further analysis of these issues see Melis, 2004).

The Role of the External Auditing Firm

In Italy, the external auditing firm is appointed by the shareholders' meeting, although the board of statutory auditors has a voice on the choice of the firm. Its appointment lasts three years. After three appointments (i.e. nine years) the law (Draghi Reform, 1998, Art. 159) requires the company to rotate its lead audit firm. Italy is the only large economy to have made auditor rotation compulsory.

Grant Thornton S.p.A. served as auditors for Parmalat Finanziaria from 1990 to 1998, when the company changed auditors to comply with the mandatory auditor rotation. In 1999 Deloitte & Touche S.p.A. took over as chief auditors.

It seems difficult to argue that auditor rotation contributed to the discovery of the accounting fraud, since Deloitte & Touche S.p.A. did not discover it during its prior audits since 1999. In fact, they never claimed any problems regarding the financial position of Parmalat in any of their reports, nor directly to CONSOB (Cardia, 2004) until they issued a review report (published on 31 October 2003) on the interim financial information for the six months ended June 2003 in which they claimed to be unable to verify the carrying value of Parmalat's investment in the Epicurum Fund, as the fund had available no published accounts nor any marked to market valuation of its assets (Parmalat Finanziaria S.p.A., 2003).

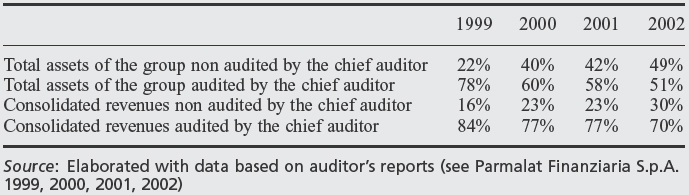

Deloitte & Touche always rendered a “nonstandard” report underlying that up to 49 per cent of total assets of the group and 30 per cent of the consolidated revenues came from subsidiaries which were audited by other auditors (see Table C15.2).

In relation to the above-mentioned amounts, Deloitte & Touche stated that their opinion was basely solely upon other auditors' reports. In fact, mandatory audit rotation was not completely effective: Grant Thornton S.p.A. continued as auditor of Parmalat S.p.A. as well as certain Parmalat off-shore subsidiaries even after 1999. This means that Deloitte & Touche had been relying on Grant Thornton's work to give their opinion about Parmalat Finanziaria consolidated financial statements.

Among other subsidiaries, Grant Thornton, specifically two of their partners who had been auditing companies related to the Tanzi groups since the 1980s,6 audited the Cayman Islands based Bonlat Financing Corporation. The latter was the wholly owned subsidiary, set up in 1998, that held the now well-known fictitious Bank of America account.

This nonexistent bank account raises fundamental questions about the role of the external auditor.

Grant Thornton claimed to have sent a request to Bank of America in December 2002 asking for confirmation of the bank account. The latter denied that they had received the request. Grant Thornton received a reply in March 2003, which was printed on Bank of America letterhead and signed by a bank employee. It is now believed that this confirmation letter was forged by Parmalat management. Grant Thornton publicly claimed that its staff acted correctly, and that the forged document made them a victim of fraud.

Table C15.2 Total assets and consolidated revenues audited by the chief auditor and other auditors

Nevertheless, even if the letter was a forgery, auditors may not label themselves as victims. Cash deposits are not complicated to evaluate, since they may be easily matched to a bank statement as part of a company's reconciliation procedures. The purpose of the third party confirmation is to ensure that bank statements received directly by the client and used in the reconciliation process have not been altered. When confirmation replies are not received on a timely basis, auditors should either send second requests or ask the client to provide a bank contact, so that they may reach the contact directly.

It is not clear whether Grant Thornton sent a second confirmation request given the time lag between the confirmation request and the response. However, they acknowledged that the request to Bank of America was done via the Parmalat chief finance director rather than getting in contact with Bank of America directly. Therefore, it seems reasonable to argue that they could have discovered the fraud if they had acted according to general auditing standards and exhibited the proper degree of professional “scepticism” in executing their audit procedures.

Prosecutors believe that the Grant Thornton auditors were too “involved” in the Bonlat issues, since the setting up of the latter was allegedly their idea to keep concealed the Parmalat financial crisis from the eyes of the incoming chief auditor Deloitte & Touche.

With regard to the Enron case, Palepu and Healy (2003) argue that the auditing firm firstly failed to exercise sound business judgement in reviewing transactions that were in fact creative accounting, i.e. only designed for financial reporting rather than business purposes. Then they “succumbed” to pressures from Enron's management. Mutatis mutandis, the Parmalat case does recall the Enron case with regard to the failure of the role of the external auditor at Parmalat as a gatekeeper, who was either not competent or (more likely in the case of Grant Thornton) not “independent”.

This side of the story seems to fit perfectly into the global corporate governance issues. Thus it is against the argument of Parmalat as a particularly Italian case.

A REVIEW OF PARMALAT'S COMPLIANCE WITH THE ITALIAN CODE OF BEST PRACTICE

In civil law based countries (like Italy), the effectiveness of codes of best practice is limited because of the lower enforceability of their recommendations in comparison with Anglo-Saxon common law based countries (Cuervo, 2002).

Even taking this limitation into account, a review of the compliance of Parmalat with some key recommendations of the Preda Code (1999, 2002) is still useful to understand to what extent Parmalat complied, at least formally, with the highest standards of corporate governance in Italy. A high level of compliance would support the “Parmalat as a particularly Italian case” hypothesis, while a low level of compliance would not support such a hypothesis.

The Role of the Board of Directors

The Preda Code (1999, 2002, para. 1) recommends that matters of special importance should be reserved for the exclusive competence of the board of directors. These include (a) the examination and approval of the company's strategic, operational and financial plans and the corporate structure of the group, and (b) the examination and approval of transactions having a significant impact on the company's profitability, assets and liabilities or financial position, with special reference to transactions involving related parties.

Cavallari et al. (2003) report that, on a sample of Italian listed companies which represented 85 per cent of total capitalisation of the markets, 85 per cent of the companies fully complied with these recommendations. Eleven per cent of the sample complied partially, and only 4 per cent did not declare explicitly to reserve any of these functions to the board of directors.

According to its company reports on corporate governance, Parmalat Finanziaria, the listed holding company of the group, had complied with these recommendations since 2001.

The Composition of the Board of Directors

The Preda Code (2002, para. 2.1) also recommends the board of directors to be composed of executive and non-executive directors. The non-executive directors should, for their number and authority, carry a significant weight in the board's decision-making process.

The board of directors of Parmalat Finanziaria was composed of 13 members. Four of them, including the Chairman-CEO, were linked by family ties.

Parmalat Finanziaria, in its 2003 report on corporate governance, claimed that among the members of its board of directors, five were to be considered as non-executive directors. The fact that non-executive directors are less than executive directors is rather unusual among Italian listed companies (see Table C15.3).

At Parmalat Finanziaria, an executive committee was set up and composed of seven directors, including three Tanzi family members. One of the allegedly non-executive directors (Barili) belonged to the executive committee, and had been working in Parmalat as senior manager from 1963 until 2000.

Table C15.3 Composition of board of directors by type of control of listed companies

With regard to the composition of the board, it is also interesting to observe that eight Parmalat Finanziaria directors also sat on the board of directors of Parmalat S.p.A., including all the members of the executive committee and one non-executive director.

The Independent Directors

The Preda Code (2002, para. 3) also recommends that an adequate number of non-executive directors should be independent in order to ensure the protection of the minority shareholders. An independent director is defined as a director who meets the following criteria:

- s/he does not entertain, directly, indirectly or on behalf of third parties, nor has s/he recently entertained, with the company, its subsidiaries, the executive directors or the shareholder or group of shareholders who control the company, business relationships of a significance able to influence their autonomous judgement;

- s/he does not own, directly or indirectly, or on behalf of third parties, a quantity of shares enabling them to control or notably influence the company or participate in shareholders' agreements to control the company;

- s/he is not close family of executive directors of the company or a person who is in the situations referred to in the above paragraphs.

Cavallari et al. (2003) report that, among the Italian listed companies, the board of directors is generally composed of five directors that may be considered as independent. Parmalat Finanziaria claimed to have three independent directors on its board.

The Separation Between the Chairperson and CEO Positions

The Preda Code (1999, 2002, para. 4, p. 9) does not explicitly recommend that the Chairperson position should be held by a non-executive director, rather it acknowledges that “it is not infrequent in Italy for the same person to hold both positions or for some management powers to be delegated to the Chairman”. When the two positions are not separated or the Chairman is delegated some executive powers, the board of directors is only recommended to provide adequate information in its annual report about the duties and responsibilities of the Chairperson and the executive directors.

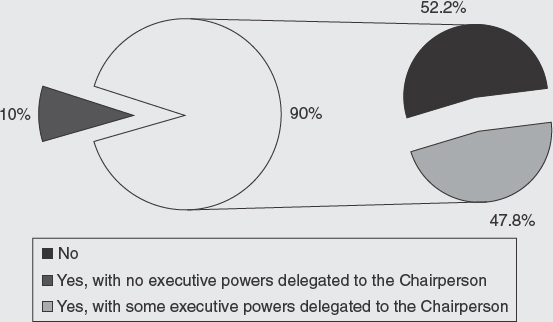

Empirical evidence shows that among MIB30-listed companies the two positions are often separated (approx. 90 per cent of the cases). However, even when the positions are separated, the division of roles between Chairperson and CEO is often not adequately clear (Melis, 1999, 2000) since the Chairperson is often given some executive powers. In fact, in total 53 per cent7 of the companies do delegate some executive powers to their Chairperson (see Figure C15.3).

At Parmalat Finanziaria, the Chairman and Chief executive director positions were not separated. Both positions were held by Tanzi. This situation led to a huge concentration of powers considering that the same person was the major shareholder of the company.

Although the separation between CEO and Chairperson is recommended by most international corporate governance codes of best practice since the Cadbury report (1992), Parmalat Finanziaria did comply with the Italian code of conduct since adequate information on the powers delegated to the Chairman/CEO was disclosed in its annual report.

Figure C15.3 Separation between Chairperson and CEO among MIB30 listed companies

Source: Elaborated with data based on CONSOB database. Data updated at December 2003

The Preda Code (1999, 2002, para. 5) recommends that the Chairperson of the executive committee periodically report to the board of directors on the activities performed in the exercise of his/her powers. At Parmalat Finanziaria this report was done quarterly. Thus it complied with this recommendation.

Confidential Information

The Preda Code (1999, 2002, para. 6) deals with the handling of confidential information and recommends companies adopt internal procedures for the internal handling and disclosure of price-sensitive information, as well as information concerning transactions that involve financial instruments, carried out by persons who have access to relevant information.

Cavallari et al. (2003) report that the great majority (90 per cent in 2003, 81 per cent in 2002 and 58 per cent in 2001) of the Italian listed companies analysed complied with this provision.

Parmalat Finanziaria had informal internal procedures until 2002, when it set up a more structured system, under the responsibility of the Chairman/ CEO Tanzi. Thus it formally complied with the Preda Code on this issue. In fact, empirical evidence shows clearly that the above-mentioned procedures that dealt with confidential information were only used to keep concealed the accounting fraud for more than a decade.

The Appointment of Directors and the Nomination Committee

With regard to the nomination process, the Preda Code (1999, 2002, para. 7.2) recommends companies set up a nomination committee to propose candidates for election in cases when the board of directors believes that it is difficult for shareholders to make proposals. This may happen in cases when the corporate ownership and control structure is dispersed.

Parmalat Finanziaria did not comply with this recommendation and explained that shareholders never faced difficulties in proposing candidates for elections. This may be considered an adequate explanation given the concentrated control structure of the company.

The choice of not setting up a nomination committee is not uncommon among Italian listed companies. Only approximately 10 per cent set up such a committee (Cavallari et al., 2003).

The Remuneration Committee

The Preda Code (1999, 2002, para. 8.1) recommends that companies set up a remuneration committee, which should be composed of mainly non-executive directors, in order to guarantee the body's impartiality. It is given the task of formulating proposals for the remuneration of managing directors and directors appointed to special offices.

Cavallari et al. (2003) reports that remuneration committees have been set up by more than 80 per cent of the companies analysed. In 95 per cent of cases these committees have mostly been composed of non-executive directors.

Parmalat Finanziaria set up the remuneration committee, which was composed of three members. Although one of them was also a member of the executive committee, the remaining two were non-executive directors. Both of them were also claimed as independent directors by the company reports. Therefore this recommendation was complied with.

Internal Control and the Role and Composition of the Internal Control Committee

The internal control committee is recommended by the Preda Code (1999, 2002, para. 10.2) to (a) assess the adequacy of the internal control system, (b) monitor the work of the corporate internal auditing staff, (c) report to the board of directors on its activity at least every six months and (d) deal with the external auditing firm. It has a similar role to that of British audit committees (see Spira, 1998; Windram and Song, 2004). It is appointed by the board of directors and should be composed of non-executive directors in order to be able to carry out its functions autonomously and independently.

The Preda Code (2002, para. 10.1) recommends that the majority of its members should be independent directors.

Cavallari et al. (2003) report that almost 90 per cent of the sample analysed adopted an internal control committee, which in over 82 per cent of the cases is entirely composed of non-executive directors, who are almost always independent.

At Parmalat Finanziaria, the internal control committee was composed of three members. Two of these members also sat in the executive committee. Thus, non-executive directors did not represent the majority of the committee. The recommendation of the Preda Code was not complied with, but no adequate explanation was given by the company in its corporate governance report.

It is also worth noting that one of the internal control committee members (Tonna) had been the chief finance director from 1987 until March 2003. He also held the Chairman position at Coloniale S.p.A., the Tanzi family holding company which was also the major shareholder of Parmalat Finanziaria.

The third member of the internal control committee, who was also the Chairman of the committee, was allegedly an independent director. However, further analysis (based on data not provided by the company) shows that he was the chartered certified accountant of the Tanzi family (as well as an old personal friend of Tanzi). Claiming that this relationship is not significant enough to influence his autonomous judgement seems difficult to argue and/or believe.

Therefore, it may be argued that none of the members of the internal control committee could have actually been considered as independent.

The Preda Code (1999, 2002, para. 3.2) acknowledges that when a group of shareholders controls a company, the need for some directors to be independent from the controlling shareholders is even more crucial. Parmalat Finanziaria failed to comply with this important recommendation, and did not give any adequate explanation for not complying.

Transactions with Related Parties

The Preda Code (1999, 2002, para. 11) recommends that transactions with related parties8 should be treated according to criteria of “substantial” and “procedural” fairness. Companies are recommended to set up a procedure to deal with these transactions. In its corporate governance report, Parmalat Finanziaria claimed to comply with this provision, although empirical evidence clearly shows that such transactions were not treated according to the above-mentioned criteria.

Relations with Institutional Investors and Other Shareholders

With regard to the relations with institutional investors and other shareholders, it is recommended (Preda Code, 1999, 2002, para. 12) to designate a person or create a corporate structure to be responsible for this function.

In its corporate governance report Parmalat Finanziaria claimed to have set up an investor relations' structure since 2001. Thus, it complied with this recommendation.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The paper examined and discussed to what extent Parmalat may be considered a particularly Italian case, or rather a case that fits into the global corporate governance argument.

The paper has looked at the role of the information supply agents (board of directors, board of statutory auditors, internal control committee, senior management and external auditing firm) in the Parmalat case.

Empirical evidence seems to confirm the lack of a monitoring structure making corporate insiders accountable in the presence of a corporate governance system characterised by a controlling shareholder.

The roles of the ownership and control structure (with special regard to the controlling shareholder's role), and of the board of statutory auditors, do have Italian traits and might suggest that Parmalat is a particularly Italian corporate governance case.

Moreover, the controlling shareholder was able to hold the positions of Chairman and CEO of Parmalat Finanziaria, which led to a huge concentration of powers. Although this concentration of positions is unusual among large Italian listed companies, the separation between the two positions is not explicitly recommended by the Italian code of best practice, so that Parmalat formally complied with it.

Although Italian corporate governance standards are not the highest at an international level, and might need improving, the standards themselves were not at fault in the Parmalat case, at least not completely.

In fact, Parmalat's corporate governance structure failed to comply with some of the key existing Italian corporate governance standards of best practice, such as the presence of independent directors, the composition of the board of directors and, especially, of the internal control committee (i.e. the audit committee).

Besides, the roles of the external auditor as well as the internal control committee as non-effective monitors seem to suggest that the Parmalat case fits, to some extent, into the global corporate governance argument and is not very different from Enron or other Anglo-American or continental European corporate scandals.

Whilst the Parmalat case may be considered to some extent a particularly Italian case, this does not imply that the corporate governance problems that emerged at Parmalat should be disregarded and catalogued as country-specific, since they may also surface at other firms around the world.

NOTES

1. Pyramidal groups, which are very widespread in Italy, have been defined as “organisations where legally independent firms are controlled by the same entrepreneur (the head of the group) through a chain of ownership relations” (Bianco and Casavola, 1999, p. 1059).

2. Prosecutors believe that Tanzi funnelled over €1.500 million to Parmatour and some other million to other Tanzi family-owned companies.

3. Since 2004 the new company law allows companies to choose between a unitary board structure (with an audit committee within the board of directors), a two-tier board structure (with a management committee and a supervisory council), and the traditional board structure with the board of statutory auditors.

4. MIB30 is the Italian equity share market segment that includes companies with a capitalisation above €800 million.

5. CONSOB (Commissione Nazionale per le Società e la Borsa) is the public authority that is responsible for regulating and controlling the Italian securities markets.

6. Mr Pecca, the President of Grant Thornton in Italy, and Mr Bianchi audited Parmalat from the 1980s, first as auditors of Hodgson Landau Brands, then as Grant Thornton.

7. In total 53 per cent of MIB30-listed companies delegate some powers to their Chairperson: 10 per cent of these companies do not separate the Chairperson and CEO positions and 43 per cent do separate the two positions.

8. See IAS 24 (IASB, 2003) for a definition of “transaction for related parties”.

REFERENCES

Becht, M. (1997) Strong Blockholders, Weak Owners and the Need of European Mandatory Disclosure. In European Corporate Governance Network (ed.), The Separation of Ownership and Control: A Survey of 7 European Countries. Preliminary Report to the European Commission. Brussels: ECGN.

Bianco, M. and Casavola, P. (1999) Italian Corporate Governance: Effects on Financial Structure and Firm Performance, European Economic Review, 43, 1057–1069.

Cadbury Report (1992) The Financial Aspects of Corporate Governance. London: Gee.

Cardia, L. (2004) I rapporti tra il sistema delle imprese, i mercati finanziari e la tutela del risparmio, Testimony of the CONSOB President at Parliament Committees VI “Finanze” and X “Attivita produttive, Commercio e Turismo”, della Camera and 6° “Finanze e Tesoro” and 10° “Industria, Commercio e Turismo” del Senato, 20 January.

Cavallari, A., Goos, E., Laorenti, F. and Sivori, M. (2003) Corporate Governance in the Italian Listed Companies. Milan: Borsa Italiana (http://www.borsaitalia.it).

CONSOB (2002) Relazione annuale 2001. Commissione Nazionale per le Società e la Borsa.

CONSOB (2003) Relazione annuale 2002. Commissione Nazionale per le Società e la Borsa.

CONSOB (2004) Relazione annuale 2003. Commissione Nazionale per le Società e la Borsa.

Cuervo, A. (2002) Corporate Governance Mechanisms: A Plea for Less Code of Good Governance and More Market Control, Corporate Governance – An International Review, 10(2), 84–93.

Draghi Reform (1998) Testo unico delle disposizioni in materia di intermediazione finanziaria, Legislative decree N. 58/1998.

Heller, R. (2003) Parmalat: A Particularly Italian Scandal, Forbes, 30 December (http://www.forbes.com).

IASB (2003) International Financial Reporting Standards – IAS 24 Related Parties Disclosures. London: IASCF.

Johnson, S., La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Sinales, F. and Shleifer, A. (2000) Tunnelling, American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, 90(2), 22–27.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Sinales, F., Shleifer, A. and Vishny, R. (1997) Legal Determinants of External Finance, Journal of Finance, 52(3), 1131–1150.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Sinales, F., Shleifer, A. and Vishny, R. (2000) Investor Protection and Corporate Governance, Journal of Financial Economics, 58(1), 3–27.

Lyman, E. (2004) Parmalat's Problems: An Italian Drama, The Washington Times, 12 January.

Macey, J. (1998) Italian Corporate Governance: One American's Perspective, Columbia Business Law Review, 1, 121–144.

Melis, A. (1999) Corporate Governance. Un'analisi empirica della realtà italiana in un'ottica europea. Torino: Giappichelli.

Melis, A. (2000) Corporate Governance in Italy, Corporate Governance – An International Review, 8(4), 347–355.

Melis, A. (2004) On the Role of the Board of Statutory Auditors in Italian Listed Companies, Corporate Governance – An International Review, 12(1), 74–84.

Melis, G. and Melis, A. (2004) Financial Reporting, Corporate Governance and Parmalat. Was it a Financial Reporting Failure? University of Cagliari Dipartimento di Ricerche aziendali working paper.

Molteni, M. (ed.) (1997) I sistemi di corporate governance nelle grandi imprese italiane. Milan: EGEA.

Mulligan, M. and Munchau, W. (2003) Comment: Parmalat Affair has Plenty of Blame to go Round, Financial Times, 29 December.

Palepu, K. and Healy, P. (2003) The Fall of Enron, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17(2), 3–26.

Parmalat Finanziaria S.p.A. (1999, 2000, 2001, 2002) Relazione e bilancio d'esercizio (Annual report).

Parmalat Finanziaria S.p.A. (2001, 2002, 2003) Informativa sul sistema di Corporate Governance ai sensi della sezione IA.2.12 delle istruzioni al Regolamento di Borsa Italiana spa (Report on Corporate Governance).

Parmalat Finanziaria S.p.A. (2003) Interim reports.

Parmalat S.p.A. (2002) Relazione e bilancio d'esercizio 2002 (Annual report).

Preda Code (1999, 2002) Codice di Autodisciplina. Milano: Borsa Italiana.

Roe, M. (1994) Strong Managers, Weak Owners. The Political Roots of American Corporate Finance. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Shleifer, A. and Vishny, R. (1986) Large Shareholders and Corporate Control, Journal of Political Economy, Part 1, June, 461–489.

Spira, L. F. (1998) An Evolutionary Perspective on Audit Committee Effectiveness, Corporate Governance – An International Review, 6(1), 29–38.

Stanghellini, L. (1999) Family and Government-owned Firms in Italy: Some Reflections on an Alternative System of Corporate Governance, Columbia Law School project on Corporate Governance, Mimeo, June.

Windram, B. and Song, J. (2004) Non-Executive Directors and the Changing Nature of Audit Committees: Evidence from UK Audit Committee Chairmen, Corporate Ownership and Control, 1(3), 108–115.

Reproduced from Corporate Governance, Vol. 13, No. 4 (July 2005), pp. 478–88.