8

Retooling Schooling

RESHAPING SUPPORT SYSTEMS

—Dr. Steven Paine, West Virginia State Superintendent of Schools

Running a good school is no simple matter. A number of complex relationships and supporting systems must all work together to bring the best possible learning experience to each and every child.

Mapping all the interactions among all the players inside and outside the school, including students, teachers, administrators, school boards, curriculum providers, parents and community members, testing agencies, and more, can result in quite an overwhelming systems diagram, as Figure 8.1 shows.

The P21 framework offers a simpler approach—one that focuses on the five traditional educational support systems familiar to educators and parents alike. To create a 21st century school system, these interlinked support systems must all work together:

• Standards

• Assessments

• Curriculum and instruction

• Professional development

• Learning environments

Figure 8.2 shows these support systems in the context of the entire P21 learning framework.

In this chapter, we first look broadly at how school systems are overhauling their educational systems for the 21st century. Later we dive into each of the support system “pools” in the P21 framework to see how standards, assessments, curriculum and instruction, professional development, and learning environments are all shifting to support 21st century learning, understanding, and skills performance. Examples from one school system, West Virginia, provide specifics on one successful approach.

Figure 8.2. 21st Century Learning Framework.

Shifting Systems in Sync

As head of public education for West Virginia, a state known for its beautiful Blue Ridge Mountains and its long association with coal mining, Steve Paine knows that his students need to move forward into the 21st century. So West Virginia got an early start with its 21st Century Learning initiative.1 The initiative focused on

• Internationally rigorous and relevant curriculum standards (including content, learning skills, and technical tool skills)

• A balanced assessment strategy

• Research-based instructional practices

• A parallel accountability system

• Aligned teacher preparation programs

• The development of a 21st century leadership continuum

• Emphasis on pre-K programs

• The integration of technology tools in every classroom

How will West Virginia schools achieve these goals? How does any school, any district, any state or province, or any nation go about transforming 20th century factory-model school systems into a network of 21st century learning centers? The future of their communities, the health of their economies, and the welfare of their citizens are entirely dependent on preparing each and every child for success in learning, work, and life.

In West Virginia, as in many other school systems working their way toward a 21st century model of teaching and learning, the answer for educators and policymakers lies in incorporating both a systematic approach and a spirit of innovation. They need to take both small, achievable steps and some large leaps in the many components of the education system and to measure progress as they go, course correcting as they learn what works and what doesn’t and celebrating their accomplishments along the way.

Many different roads are being traveled in the global movement toward 21st century education systems, but some common patterns and principles are starting to emerge. Looking at a variety of worldwide reports of successful efforts to move toward a 21st century education system, such as the United Kingdom’s “Harnessing Technology: Next Generation Learning 2008-14”2 and the Singapore “Teach Less, Learn More” Initiative,3 as well as the work of the Partnership for 21st Century Skills, we see six emerging principles that these initiatives all seem to share:

• Vision

• Coordination

• Official policy

• Leadership

• Learning technology

• Teacher learning

Vision

A common and well-articulated vision of 21st century learning needs to be shared among educators, government officials, the business community, parents, and students. This common vision helps the key stakeholders sustain the long-term commitment it takes to transform the education system over time.

To help create that common vision, the P21 Learning Framework, consensus-building activities such as the Four Questions exercise described in the Introduction, effective community information campaigns, and sustained local public communications efforts can all be helpful.

Coordination

All the educational support systems—standards, assessment, curriculum and instruction, professional development, and learning environments—must work together in a coordinated way to support 21st century learning.

Often changes are made in one support system, such as a new curriculum, without coordinated changes being made in all the other linked systems: the learning environment, teacher professional development, aligned assessments and standards, for example. These isolated changes may generate enthusiasm for a while, but without the support necessary from the other systems to sustain the change, they almost always become short-lived “experiments.”

Official Policy

Successful initiatives that are making 21st century education improvements stick have their new innovations codified into the education systems’ governing policy documents; into the official learning standards, goals, and objectives; and into the assessment and accountability practices required by the governing education authority (more on each of these systems shortly).

Additionally, sustainable initiatives commit adequate funding during the transformation period—at least five to seven years, and sometimes more. Funding needs to support the long-term planning and phased implementation of such a large-scale change initiative. This funding commitment mostly involves shifting existing funding to new activities, though some additional funding for teacher development and improved technology infrastructure is likely to be needed during the transition to a 21st century model.

These measures help ensure that changes in everyday teaching methods, the curriculum, and the learning environment of a school will continue to work in concert toward supporting solid 21st century learning goals, and that there will be time and resources for learning innovations to take hold and be refined.

Leadership

Developing a successful 21st century education program requires both distributed and coordinated leadership. Authority and decision making must rest with those most capable of making a good decision, and technology must be used to communicate and coordinate action efficiently. Those involved need to take the time to learn from each other’s experiences (successes and setbacks) as new methods and processes are innovated.

As a result, education leaders at all levels (national, state or province, district, school, and classroom) must firmly and consistently lead all stakeholders—students, parents, teachers, administrators, government officials, community members—toward the same 21st century learning goals of rigorous and relevant knowledge, understanding, and proficiency in 21st century skills. All these leaders must also openly and frequently communicate progress toward these goals and encourage experimentation and innovations in creating a successful 21st century education system.

Learning Technology

Providing students easy access to the Internet in the classroom, as well as to laptop computers, handheld devices, and other learning technologies, is a vital part of any 21st century education redesign. But the technology must also be focused on supporting each student’s 21st century learning goals.

Administrative technology (student information databases, assessment tracking systems, school portals, class management systems, parent communications, video monitoring, and the like) should be used to automate much of the administrivia of running a school or education system, freeing time and resources to support quality teaching and effective 21st century student learning.

Teacher Learning

In all successful transformations, professional development of both new and practicing teachers is a top priority of education leaders. Teachers must become 21st century learners themselves, learning from inquiry, design, and collaborative approaches that build a strong community of professional educators.

Teachers, whether they are fresh out of an education school or have been in the classroom for twenty years, must learn to develop their design, coaching, and facilitating skills to guide and support their students’ learning projects. Teachers must continually sharpen their skills at using the power of learning technologies to help deepen understanding and further develop 21st century skills.

These teaching methods are a break from the past. They have not been commonly taught in schools of education or widely available in teacher professional development programs. Yet the rising demand for 21st century skills and the teaching methods that build them are rapidly changing this situation; education schools such as Columbia Teachers College in New York City and many teacher professional development programs around the world are shifting toward a 21st century teacher education model that includes practice in designing and implementing inquiry, design, and collaborative learning projects, bringing many more opportunities for teachers to master 21st century teaching methods.

Support Systems

Each of the traditional educational support systems is being reshaped to help build successful 21st century schools and learning communities. The following sections review some of the progress being made in these systems.

Standards

Standards are designed to answer the question: What should our children be learning? Standards documents in the 20th century were typically long lists of the content students should know in a certain subject at a certain age or grade level.

For the 21st century, standards emphasize what students should be able to do with this content—defining the skills students can employ when applying the content to useful work in each subject area. These 21st century standards also include levels of mastery for a given standard, from novice level to expert.

For example, Table 8.1 shows part of a redesigned 21st century Content Standard for Grade 5 Science from the West Virginia learning standards.

Though approaches to standards vary around the world, there has been a trend in the last decade to create very detailed standards that cover a huge number of content topics. In these “mile-wide and inch-deep”4 standards it has been estimated that in some cases it would take as many as twenty-two years of schooling to adequately teach all the content identified in a set of elementary school standards documents!

It could also take a long time to test students’ knowledge of all this content—so test designers test only a small fraction of the standards each year, changing which items they test every year.

In many ways, standards have been designed for the way we test. Standards have been limited to the types of knowledge best tested by the multiple-choice questions on the machine-scored tests so commonly used to measure student progress.

This has led teachers to focus on “coverage,” superficially rushing through a vast number of topics with their students, and to emphasize memorization and recall in preparation for the end-of-year, high-stakes standards-based tests that determine so much of a student’s future learning path.5

Table 8.1. Grade 5 Science Standard from West Virginia.

Though many schools in many countries have begun moving in a more 21st century direction, this teach-to-the-test trend has truly been a global phenomenon. A recent international survey of teachers in twenty-three countries in North America, Europe, Asia, Latin America, and Africa found that the three most common teaching practices in schools were filling out worksheets, having students individually working at the same pace and sequence on the same tasks, and answering tests.6

This leaves little time for deep dives into topics, for depth of understanding, or for the mastery of the 21st century skills, and almost no time for collaborative explorations of questions, issues, or real-world problems that might engage students in their learning.

So how do we move from this 20th century standards model to a 21st century model?

As they say in Singapore, “Teach Less, Learn More.” Focus the standards on a short list of the big ideas in each subject area. Make sure that often-neglected topics that have real-world relevance for students are included (statistics and probabilities in math, the human-made world of technology in science, and the like). And include and embed 21st century skills as part of the learning standards.

As an example, here are three of West Virginia’s Grades 5-8 21st Century Skills Standards:

Standard 1: Information and Communication Skills: The student will access, analyze, manage, integrate, evaluate, and create information in a variety of forms using appropriate technology skills and communicate that information in an appropriate oral, written, or multimedia format.

Standard 2: Thinking and Reasoning Skills: The student will demonstrate the ability to explore and develop new ideas, to intentionally apply sound reasoning processes and to frame, analyze and solve complex problems using appropriate technology tools.

Standard 3: Personal and Workplace Skills: The student will exhibit leadership, ethical behavior, respect for others; accept responsibility for personal actions considering the impact on others; take the initiative to plan and execute tasks; and interact productively as a member of a group.

Standards should focus on real-world problems that promote learning across the disciplines using 21st century themes and interdisciplinary issues. Incorporating fast-developing cross-discipline areas of knowledge, such as bioengineering and green energy technologies, will help develop the skills needed for the kinds of career opportunities likely to be available when students enter the job market.

Standards also need to be designed such that the depth increases as students progress through the grade levels, investigating various aspects of a “big idea” over time. This way, understanding builds on earlier work and skill mastery increases over time. An example would be learning about ancient Greek culture in Grade 4, Athenian democracy in Grade 8, and comparative Greek and other political philosophies and practices in Grade 12.

Multiple methods must be used to assess performance on the standards, especially on 21st century skills performance. These assessment methods may include evaluations of portfolios of student project work, classroom observations and performance rubrics, online quizzes and simulation-based assessments, juried presentations, and juried exhibits or performances.

Assessments

The problem is not that teachers teach to the test, but that teachers need tests worth teaching to.

—Lauren and Daniel Resnick, 1992

Assessment of student skills and knowledge is essential to guide learning and provide feedback to both students and teachers on how well they are all doing in reaching desired 21st century learning goals.

“You get what you measure” is often said about educational assessment, and the decades-long trend toward narrow, high-stakes tests of content knowledge in a few subject areas (language arts, math, science, and social studies) has made another saying popular: “Teach to the test.”

Recent standards and assessment practices have focused students on memorizing the content that will be required for high-stakes exams. These often-stressful exams can determine the future learning and career path of a student and are also used (and often misused) to judge the quality of an entire school and the educators in it.

The strong focus on after-instruction tests, or summative assessments, has downplayed the value of during-instruction evaluations, or formative assessments. Formative assessments, like quizzes and lab reports, are often called “assessments for learning,” as opposed to summative “assessments of learning.” Formative assessments can be more valuable to both students and teachers than summative ones, as they provide feedback in real time and allow for quick adjustments in instruction to better meet the students’ immediate learning needs.

The focus on high-stakes summative tests has also deemphasized the value of a whole range of other more authentic assessment methods from extended essays and peer- and self-evaluations to project work judged by evaluation rubrics or by a panel of experts (like the SARS Web site in the ThinkQuest competition described earlier).

Sadly, students who have special learning needs, have difficulty in reading, or are second-language learners often perform poorly on all the standardized multiple choice tests because these tests are so dependent on reading skills. Though accommodations do exist, many special needs students are simply left out of the assessment process.

What has also been glaringly left out in recent assessment practice is the measurement of essential 21st century skills and the deeper understandings and applied knowledge that can come from rigorous learning projects.

So how do we move to a new balance of 21st century assessments that provide useful feedback on students’ progress in understanding a learning topic or their gains in 21st century skills, as well as measuring a much wider range of capacities and abilities that better reflect the whole learner?

We need better summative tests and formative evaluations that measure a combination of content knowledge, basic skills, higher-order thinking skills, deeper comprehension and understanding, applied knowledge, and 21 st century skills performance. Evaluations embedded into ongoing learning activities that provide timely feedback and suggest additional learning activities that can improve understanding and performance would also be very helpful.

If a single test measures both basic and applied skills, there is no need for more tests, just better tests that measure more of what students need for success in the 21st century.7 Figure 8.3 shows an example from a West Virginia Grade 11 Social Studies summative test item that moves beyond measuring memorized facts. To lower costs, this test is being delivered electronically instead of on paper.

Another good example of a more authentic 21st century assessment is the College Work and Readiness Assessment (CWRA), developed by the Council for Aid to Education and the RAND Corporation. Students use research reports, budgets, and other documents to help craft an answer to a complex problem, such as how to manage traffic congestion caused by population growth. As one ninth-grade student said after taking the CWRA test, “I proposed a new transportation system for the city—it’s expensive, but it will cut pollution.”8

We need to use a wide variety of real-time formative assessments that measure content knowledge, basic and higher-order thinking skills, comprehension and understanding, and applied 21st century skills performance. Many effective methods to assess ongoing learning progress are available; here are just a few: Collections of formative assessments can also be used as part of a summative evaluation, offering a rich set of multiple measures as the basis for an end-of-project or end-of-unit assessment of progress toward learning goals and standards.

Collections of formative assessments can also be used as part of a summative evaluation, offering a rich set of multiple measures as the basis for an end-of-project or end-of-unit assessment of progress toward learning goals and standards.

• Extended student essays

• Observation rubrics on a teacher’s handheld device

• Online instant polls, quizzes, voting, and blog commentaries

Figure 8.3. West Virginia Grade 11 Social Studies Test Question.

• Progress tracked in solving online simulation challenges and design problems

• Portfolio evaluations of current project work and mid-project reviews

• Expert evaluations of ongoing internship and service work in the community

Technology-based assessments can automate some of the labor-intensive tasks of assessing student performance and offer new ways to evaluate skills performance, especially through the use of problem scenarios and simulations based on real-world situations.

Because assessments tend to drive all the rest of the education support systems, a number of promising national and global initiatives are under way to design a core set of balanced 21st century assessments that truly align with the kinds of deeper understanding and skills performance so needed in our times. These 21st century assessments promise to provide a much broader picture of the full capabilities of the “whole child”—including the cognitive, emotional, physical, social, and ethical aspects of a healthy, safe, engaged, supported, and positively challenged student.9

Curriculum and Instruction

So far we have discussed a number of features of effective 21st century learning methods and a model of a 21st century approach to instruction using inquiry, design, and collaborative learning projects. A curriculum based on a blend of these learning methods with more direct forms of instruction is what is now needed to build knowledge, understanding, creativity, and other 21st century skills.

An encouraging sign that 21st century learning methods are taking hold is the recent announcement that the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has stopped presenting introductory physics in large-lecture format (more than three hundred students) and is instead having small student teams do hands-on labs, interactive computer-based activities, and video-based mini-lectures. As a result, class attendance is up and the course failure rate has dropped by 50 percent.10

So what should shift in curriculum and instruction to reach a new 21st century balance?

A reasonable goal for most education systems moving from a 20th century model to a 21st century one might be 50 percent time for inquiry, design, and collaborative project learning and 50 percent for more traditional and direct methods of instruction. Once this goal is achieved, more and more of the direct instruction will occur in the context of questions and problems that arise in learning projects and need addressing so that students can move their project work forward. The lessons delivered this way gain greater relevance and are more likely to be remembered.

Designing and sequencing engaging learning projects so that they meet learning standards and increasingly deepen understanding and build 21st century skills as a student progresses through school will be a challenge for many education systems. Fortunately, a growing number of online libraries and repositories contain a wealth of effective learning projects that will be helpful in developing this type of multi-year project- or unit-based curriculum. (See Appendix A.)

Online and distance learning courses, also based on a project approach, can supplement a school’s curriculum, especially where local teachers aren’t available to teach certain courses.

Teacher Professional Development

The success of the 21st century skills movement depends on altering what goes on each day in the world’s classrooms and schools. Teachers are the front line in this change, and they must have the knowledge, skills, and support to be effective 21st century teachers.

Teacher professional development programs, for both new teachers-in-training and working teachers, are taking up the challenge. They have begun providing the learning experiences necessary to prepare teachers to incorporate inquiry, design, and collaborative project teaching methods and to use technology and assessments of 21st century skills effectively in their everyday classroom work.

One good example of a concerted effort to bring 21st century learning approaches to a large teacher community is West Virginia’s effort to teach project learning methods to all the teachers in the state. Using a variety of professional development offerings including the Intel Teach program and Oracle Education Foundation’s Project Learning Institute (a video documentary on this Institute and the resulting project is available on the included DVD and on the book’s Web site), as well as state and district-developed programs, West Virginia teachers are honing their own 21st century skills as they learn how to teach these skills to their students.

A West Virginia Teacher’s Success Project

In 2007 fifth-grade teacher Deb Austin Brown of St. Albans Elementary joined eighty educators from around the globe to learn how to design and lead engaging learning projects that build 21st century skills and deepen understanding of school subjects. She learned how to lead and support all the phases of a learning project: define, plan, do, review, and manage through the project cycle.

With the help of other teachers from around the world and an online project environment with tools and digital space to hold all the project work, Deb designed what she called The Success Project. Students chose a successful historical or contemporary leader, researched what helped make that leader a success, and created Web pages that captured their findings. They received feedback and comments on their Web pages from other students around the world (students of some of the international teachers Deb met in the training). They then presented their findings to other students, teachers, parents, and community leaders at a school exhibition.

Ryan, one of Deb’s highly engaged and ambitious fifth-grade students, continued developing his success skills by interviewing a prominent high-tech business leader in the community, and even the governor of West Virginia.

Deb’s Success Project certainly empowered Ryan to be a more successful 21st century learner and a future leader.

Successful professional development programs that give teachers the knowledge, tools, and practice to be effective 21st century teachers have a number of common characteristics.11 These programs tend to be

• Experiential, engaging teachers in the concrete tasks of designing, implementing, managing, and assessing learning activities and projects, and observing other teachers’ methods and skills, which helps to clarify their own values and beliefs in what makes learning effective

• Grounded in a teacher’s own questions, problems, issues, and challenges, as well as what professional research has to offer

• Collaborative, using the collective experience and expertise of other teachers and the wider community of educators exploring 21st century learning methods

• Connected to a teacher’s own work with students and the teacher’s curriculum and school culture, as well as connected with technology to the wider world of learning

• Sustained and intensive, with ongoing support by modeling, coaching, mentoring, and collaborative problem solving with other teachers and administrators on issues of teaching practice

• Integrated with all other aspects of school change, reform, and transformation

Strong, continuous investments in 21st century teacher professional development will be essential to the transformation of education systems around the globe. They will need to be well coordinated with ongoing changes in curriculum, assessment, standards, and the overall learning environment.

Learning Environments

A 21st century learning environment includes a number of important elements that work together to support 21st century teaching and learning:

• The physical buildings, classrooms, and facilities, and their design

• A school’s daily operations, scheduling, courses, and activities

• The educational technology infrastructure

• The professional community of teachers, administrators, and others

• The culture of the school

• Community involvement and participation

• The education system’s leadership and policies

To support the unique learning needs of each child and to create the conditions in which 21st century learning can best happen, new learning structures, tools, and relationships must be created. Building 21st century “whole environments for the whole child” involves changes in the educational use of space and time, technology, and communities and leadership.12

Learning Space and Time Learning in the 21st century is expanding the boundaries of space and time. As access to the Internet grows, more learning is happening online, after school, at home, in libraries and cafés. Learning is becoming an anytime, anyplace activity, more woven into all the parts of everyday life.

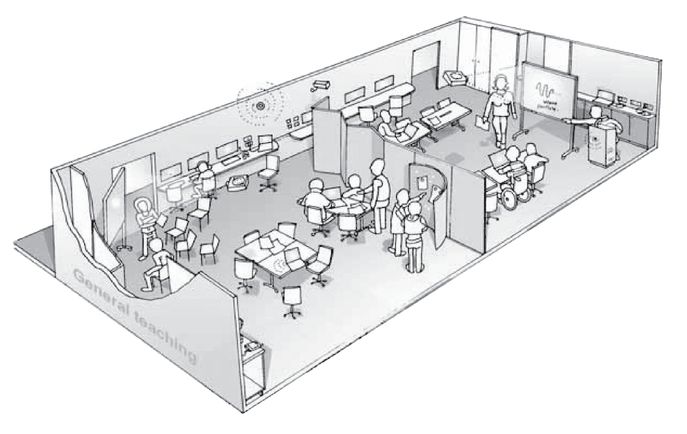

The physical environments for learning—school buildings and facilities—must also meet the challenge of becoming more flexible, to accommodate a wider variety of student, teacher, and technology interactions and activities, as illustrated in Figure 8.4.

Space for project work, group presentations, individual study and research, teamwork at a computer, performance spaces, labs and workshops for experiments and design projects, and areas for sports and recreation must all be accommodated in 21st century school designs. A flexible “learning studio” approach that can be reconfigured when needed will be an important part of the blueprint for 21st century learning.

These classrooms and school facilities will also have to tackle the challenge of becoming “green”—being more environmentally responsible in the use of energy and materials. This presents a wonderful opportunity to use the school environment itself as a learning laboratory for improving energy efficiency and water conservation, and for growing food in school gardens and mini-farms to be used in school and community meals.

Figure 8.4. New Learning Environments.

Schools can also become learning centers for the surrounding community, and as they do, community use of the school facilities will become an important design goal for schools. Schools as community learning and service centers, with health, child care, family, social, cultural, gardening, hobby, and recreational services available on the same campus, is an important trend that will only grow as schools move to incorporate more authentic community-based learning projects into their daily schedules. The community comes to the school, and the school becomes more a vital part of community life. A large number of successful examples of community schools are already in action, including many in Chicago, Houston, and Philadelphia; 13 others in countries with strong national investments in social and education programs like Denmark, Holland, Finland, Sweden, and France; and in rural areas in developing countries across the world, where schools can serve as the social and cultural hub for the village.

Flexibility in the use of time will also be a challenge to the operational design of schools. The agrarian calendar with summers off and the industrial fifty-minute period marked by ringing bells will give way to flexible schedules, year-round schools, open after-school and weekend hours, and time for extended project work and community service activities. Time for teachers to collaborate and plan rich learning activities and projects will also be an essential part of a 21st century school calendar.

Learning with Technology Unquestionably, technology can provide great benefits to learners, supporting their development of 21st century skills and knowledge. In 21st century schools, a robust technology infrastructure that can handle a wide variety of digital learning tools and devices with always-on access to the broadband Internet will be as important as electricity, lighting, and running water. Research has shown that student learning gains are greatest when technology is seamlessly integrated with rich learning content, sound principles of learning, high-quality teaching, and an aligned system of assessments, standards, and quality learning experiences geared to the needs of each child.14 The challenge now is to apply the right tools for the right learning task from the wildly expanding list of learning technologies and tools. Mobile tools will be especially important in this anyplace, anytime learning world, along with the ability for students, groups, and teachers to keep all their work safely stored, organized, and easily accessible online.

As noted, our net generation digital-native learners can help support each other and their teachers in the best use of technology for learning activities and projects in the 21st century curriculum. Students and teachers will work more as a team (and—with parents, siblings, and other community members involved—more as a whole learning community) in determining the best learning paths and tools to support each student’s learning program.

The learning and thinking power tools of our times and of the times to come are well suited for the kinds of learning experiences most needed to develop 21st century skills—the inquiry, design, and collaborative learning projects that deal with real-world problems, issues, questions, and challenges.

Learning Communities and Leadership It can take more than a village these days to educate a child.

The network of people and resources involved in providing educational opportunities to a child can be truly global, as the story in the sidebar “Keys to the 21st Century Learning Community” illustrates. The story is also documented in a video on the DVD included with this book and on this book’s Web site at www.21stcenturybook.com.

Harry from Ghana was supported and encouraged by family members, by his teachers and school administrators, by his student teammates in other countries, by educators from around the world who judged his work and gave him feedback, and by international foundations and government agencies that sponsored educational competitions.

Through determination, a supportive school community, and the concerted application of a number of 21st century skills, Harry was able to engage in a global learning community and find opportunities to further his own learning and career.

Learning environments across the globe will increasingly provide these kinds of opportunities to students. Students everywhere will be a part of an open, global learning community with strong local leadership that creates a culture of opportunity, trust, and caring.

Similarly, successful 21st century education leaders will be those who focus on the learning needs of each student and who provide the support needed by their entire professional learning community—teachers, administrators, and parents. They will be leaders who are always outward looking, searching for new learning opportunities in the world outside their school or country, and who demonstrate caring for the well-being and whole development of their students and staff.15

Keys to the 21st Century Learning Community

Harry grew up in a village on the outskirts of Kumasi, a city north of Ghana’s coastal capital, Accra. His local high school was just introducing computers into the curriculum when he entered. Harry was not sure about these machines at first, but eventually he understood just what a computer could do and suddenly he saw his future before him.

To Harry, the computer was the digital key to connecting to the rest of the world, and a passport to greater opportunities than his village could provide. He also saw that he could help other students like himself take hold of this key and use it to better their lives.

With the encouragement of his computer teacher, Harry entered a ThinkQuest competition and helped create a Web site on sea mammals. But without a computer of his own (a very expensive item in Ghana), Harry had to walk miles on a bush trail each day to the only Internet café within reach and use his small allowance to pay for computer time. He worked online for months with students from the United States and Australia. When he found out his team had won an award, Harry was thrilled—all his hard work had paid off.

Harry went on to enter a number of other Web-based competitions, still without a computer of his own, hoping to eventually have enough money from prizes in these competitions to buy his own computer. Harry continued to help other students in Ghana learn how to communicate, collaborate, and learn with computers, as he worked on developing better and better Web sites. One competition brought Harry to the United States to receive a “Doors to Diplomacy” award from the U.S. State Department.

Harry was invited to speak about his experience in using technology to learn 21st century skills at a ThinkQuest meeting around the time of his U.S. trip. After his presentation, Harry was stunned to see his wish granted—in celebration of his achievements despite the tremendous challenges he faced, Harry was presented a laptop computer of his own.

Harry has continued his career in helping others in his country and around the world use technology to open doors to learning and opportunity.

Successful education leaders will also build partnerships with businesses, foundations, nonprofit educational organizations, community groups, and other schools and educational institutions across the globe. This will bring new opportunities for their students and teachers to collaborate and learn from a world of experts and other learners, preparing them for work and life in the truly global village of the 21st century.

From Skills to Expertise: Future Learning Frameworks

Designing, redesigning, creating, and re-creating the education systems that will support 21st century learning will not be easy, and there will be many difficult obstacles to surmount as we move through a time of great change and great opportunity in the world.

We are fortunate to have a large and growing number of schools, school networks, states, countries, and enthusiastic and committed education leaders and teachers that have already achieved a great deal of progress in moving education into the 21st century. Their pioneering efforts to chart new paths for learning provide us with hope, confidence, and inspiration that we can achieve a better way of learning that better prepares our children for our times and the times to come.

However, a century is a long time, and change is the only dependable constant. As we move through the 21st century, we will need to invent new learning solutions, new school designs, and new ways to prepare our students for the future—21st century learning is clearly a work in progress.

As Alan Kay, a particularly farsighted technologist and educator, once said, “The best way to predict the future is to invent it.”

As discussed in Chapter One, expertise is highly valued in a knowledge-and-innovation society. Figure 8.5 recaps its place as the most critical link in the value chain of 21st century work.

In the 21st century, learning can be viewed as using the best methods available to produce a wide variety of experts with deep understanding and the ability to successfully apply what they know to the important questions and problems of our times.

But exactly what makes an expert different from a novice?

Thanks to decades of research in cognitive psychology, neuroscience, and other learning sciences, we have a great deal of “expertise on expertise”—knowledge of how experts think and use their knowledge and skills. 16 We now know that experts

• Notice important patterns and features that novices miss—like climatologists connecting increasing amounts of atmospheric carbon dioxide with rising global temperatures

• Have an extensive internal database of content knowledge and experience organized around powerful principles and deep understandings—such as a lawyer who knows the significant parts of case law that relate to a consumer safety lawsuit

significant parts of case law that relate to a consumer safety lawsuit

Figure 8.5 Knowledge Age Value Chain.

• Can easily select from their deep knowledge base just those facts, principles, and processes most applicable to the problem or issue at hand—such as a doctor knowing just the right combination of treatments for a certain type of lung infection

• Can retrieve the relevant parts of their knowledge quickly and without much mental effort—like a seasoned auto mechanic who can instantly diagnose a car’s problem from the sounds its engine makes

We also know that experts use the power of learning tools and technologies in more effective and efficient ways than novices. Experts use their digital thinking tools to continually expand, organize, and deepen their expertise and to help apply their knowledge and skills to new and more complex challenges.

Experts are often quite passionate about their field of expertise. They share common motivations, values, attitudes, and beliefs with others in their professional community and care deeply about the issues and dilemmas that challenge their profession. Knowledge, skills, thinking tools, motivations, values, attitudes, beliefs, communities of practice, and professional identity—all are vital parts of an expert’s world.

As we move further along into the 21st century, engaged and passionate learners and teachers will share more of these expert qualities and will model their learning after the learning practices of experts.

So how will this affect our current 21st century learning frameworks and models?

The distinctions between knowledge and skills in the current P21 rainbow model may give way to a more holistic model that puts the learner at the center of increasingly wider concentric rings of learning support, as shown in Figure 8.6.

In this model, “whole learners” with all their developing facets of expertise—knowledge, skills, motivations, values, attitudes, beliefs, feelings, health, safety, resilience, and other qualities—are placed at the center.

Learners are immediately surrounded by those who influence their learning most—other students and peers, parents, family, teachers, experts, and the rest.

Whole learning environments—the entire collection of places, tools, technologies, community resources, informal education spaces like museums and art studios, and formal educational supports such as learning standards, assessments, teacher professional development, leadership and educational policy—are all parts of the next ring of the model.

Learning communities and learning societies are the next two outward rings. The networks of people, places, and objects that accompany students on their learning travels are the main components of learning communities, and learning societies are a country’s national (and increasingly international) educational institutions and cultural services that support a student’s education.

The concentric rings of this model are set in the larger world of learning—the physical worlds of experience and the mental worlds of knowledge, skills, and expertise.

Figure 8.6. Possible Future 21st Century Learning Framework.

As we move further into the 21st century, more and more countries will put more and more emphasis on learning. They will embed learning experiences into all aspects of life and culture and become learning societies that put a high-quality education for all their citizens at the top of the list of their nation’s priorities.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.