AT THE POINT OF EXECUTION

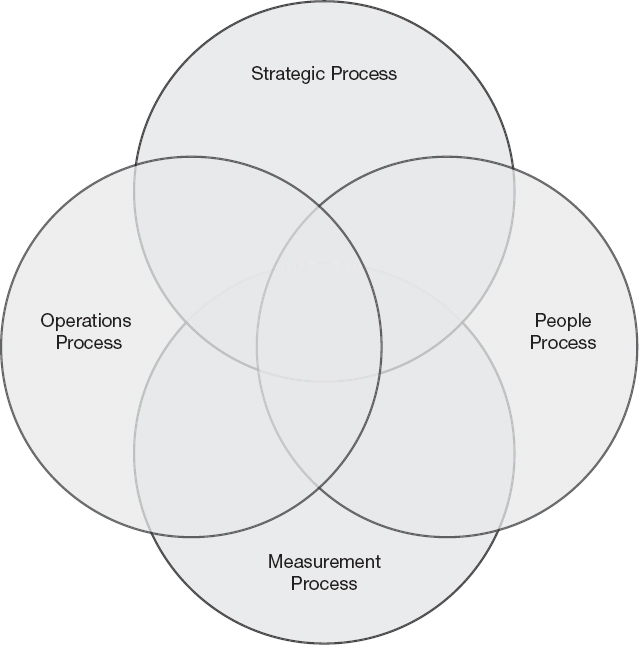

,You have the right team in place with people who are aligned with the values of the organization, who have helped develop a clear direction, who understand what's being communicated, and who are truly motivated to succeed. As a leader, you need to remain disciplined and focused enough to make sure that the following management processes are in place in order for implementation and execution to occur. These processes—strategic, people, operations, and measurement—must work in tandem, instead of occurring in four disconnected phases:

The four management processes required for execution.

The Strategic Process

The strategic process determines where you are today, where you want to go, and what you want to become. A strategic process is different from a strategic plan, which often connotes something that is put in a three-ring binder and stored in a credenza, never to be used again. The strategic process is living and vital. It identifies all the key issues, opportunities, and alternatives that are materializing, from technology to competitive intelligence. For people who do this well, the strategic process is continuous and ongoing. You don't start in January, end in March, and consider it done. The strategic process functions as a high-level road map that you constantly refer to and update in order to take the company in a specific direction.

At Baxter, we had a strategic process that constantly generated ideas that could have a significant impact on the company. Several teams would be assigned to further develop these ideas. When we reconvened as a management team, we would spend at least a portion of each meeting discussing these new ideas and the progress made on their implementation. The strategic process involved constantly thinking through how the ideas we generated would move the company into the future as we envisioned. Each team would then be held accountable for a particular initiative to transform ideas into reality.

A strong strategic process applies equally to nonprofit organizations and for-profit companies. Over the past several years, I have become more involved in the nonprofit sector, including serving on several boards. At every meeting, we compare ourselves to similar institutions. For example, at my undergraduate alma mater Lawrence University, where I served for several years as the chairman of the board of trustees, we focused on becoming one of the top liberal arts colleges in the country. We spent at least as much time in the strategic process (as well as the other three) as a for-profit company would.

The People Process

In Chapter Six, we explored the importance of having the right people in place who are aligned with the values of the organization. Your objective as the leader is to put together a high-performance team as you manage talent and develop future leaders. The people process revisits this theme to make sure that you really do have the people in place who are able to execute on the vision that you established in the strategic process.

Focusing on the people process, we can see how things can get derailed at times. I have sat through numerous presentations by leaders of a $100 million division who had a vision of growing into a $1 billion company. They focused on the products, services, and market opportunities that they believed would take them there. But they often forgot to address what I consider to be the most important element: the people side of this transformation. When I would ask a simple question, “How are you going to do this?” the response was often, “We're going to hire a bunch of great people.” I don't think it's that easy.

You can't increase the size of a business tenfold without substantially increasing the talent pool. You need the right people with the appropriate skill sets that will support a billion-dollar business. It's more than just giving the people who are currently on the team feedback and evaluating their performance. The company will require expertise in areas tomorrow that don't exist today.

Critical to the people process is involving HR. During my years at Baxter, I could not imagine holding a management meeting without the senior HR executives in the room. Human resources leadership is critical to linking the strategic process to the people process, but the benefits do not end there. HR executives can help assess the capabilities of the top executives in the company. When I was the CEO at Baxter, after the strategic process meetings concluded, I would immediately sit down with the HR executives to receive their feedback on the strengths and development needs of the senior leaders who had just presented their plans. This helped me assess the people who were running a $100 million unit, as well as discern their ability to build a billion-dollar business. If I had neglected this step and merely gone on to the next meeting, it would have been difficult to remember what someone did or did not do well during the strategic process meeting. By involving HR, I had more information with which to provide feedback to my leadership team, including information that addressed their development needs.

The Operations Process

With the strategic and people processes ongoing, it's time to examine the operations process, which some people refer to as the operating plan or budget. In this process, the focus shifts from our vision for the future to what is happening right here, right now. Although it is great to have detailed plans describing where the company is going and the people we need to get us there, too often there is little or no connection to what is going to happen in the next twelve months to move the organization in the right direction. Let's not forget that we are managing both the short term and the long term.

The operations process is where the proverbial rubber hits the road. The company needs to outline the steps required to achieve the opportunities uncovered through the strategic process. The companies that fail to have an adequate operations process will not succeed. Instead, they live in the strategic process world, where they know what they want to do in five years but never get to the discussion of what they need to do to get there. Sometimes a fascinating and intellectually stimulating strategic process can become completely disconnected from the need to execute during the next twelve months. A manager who just painted a sweeping scenario of growth and potential now says, “You're not going to hold me accountable to the first year of the strategic plan when I develop my operating budget, are you? Oh, I was just thinking about the big picture—not what's actually happening today.” In fact, the operating budget should reflect the first year of the strategic process. How can the future potential possibly be realized if it is not grounded in how the organization is operating today?

We're all too familiar with five-year plans that show the “hockey-stick” charts. The next several years will be flat, but then the expected growth will zoom into the future, resembling the steep slope of a hockey stick. When the organization fails to forge a real link between the short-term operations process and the potential envisioned in the long-term strategic process, the same charts are going to be used the next year and the year after that. All they can do is predict growth in the future, but the company never seems to get there. If the business were being managed for the next five years, however, the charts would show some relationship to the strategic plans of each of the prior years. Otherwise, there is no real progress because the company lives in a perennial five-year planning world.

Back when I was a junior analyst, I listened to a division president as he made a presentation to a senior executive. The executive smiled throughout the presentation; finally the division president asked him why. The senior executive told him, “Last night, I had a dream. I was in the middle of the fifth year of your plan. It was a remarkable place—strong growth, incredible return, high cash flow. Then I woke up, and I was once again in the first year of your plan—low growth, low return, the part where it takes money to make money. And I kept thinking to myself, ‘Boy, when will we get to the fifth year when we will experience all that fantastic growth and return?’ But we never get there. It's always the same scene playing over and over.”

“Wait til next year” may be the refrain in baseball when your favorite team fails to win the pennant, but it doesn't work with companies, and you certainly won't be a leader for very long if you don't win games. For your company to make things happen, the strategic, people, and operating processes must be tied together. As important as it is to have a long-term view, you must map out the next twelve months to help you achieve your vision in real time.

The Measurement Process

The fourth process, which is often the most neglected, is measurement. As they say, what gets measured gets done. This is equally true for small companies, large organizations, and everything in between. Unless there is a measurement process, nothing will happen. If you say reducing expenses is important but you spend all your time talking about sales and unit volumes, you should not be surprised when you discover nobody is focusing on cash flow. If the senior leader is not talking about it, no one else is either. After all, people pay most attention to those things on which they believe senior management is focusing.

Back when I was a vice president of finance, I worked for a group vice president who had eight divisions reporting to him. In our meetings, the group vice president would focus on particular priorities, such as cash flow. Later on, when it was time for follow-up meetings, as I helped prepare questions for each of the divisions, I would remind the group vice president about his prior comments regarding the importance of cash flow. If I was the only one mentioning it in the meeting, the division presidents would be staring out the window waiting for the “numbers guy” to stop talking so that they could showcase their sales and marketing efforts. Whatever the boss talked about, however, instantly became the priority. If the group vice president clearly was focused on cash flow, the division presidents and their staff would be sure to measure and monitor it.

Although measuring is very important, you have to strike the right balance between making sure you have the metrics and becoming overburdened with reports. This is a valid concern, because the temptation can be to focus on the reports alone and never take action. My advice is to do reporting on an exception basis. In other words, if there are twenty divisions that are within x percent of their operating goals, then when you are in a leadership position, such as a division president, you would not need to see these reports. The reports you want to see are from the divisions that are either underperforming or overperforming. Dealing with reports on an exception basis reduces the information overload that is always a danger when a major emphasis is placed on measurement.

To further reduce information overload, you should eliminate the reports that nobody ever looks at. This may seem obvious, but here's what often happens in the real world: a senior executive in a large organization asks for a specific report to be put together; subsequently, the preparation of the report becomes engrained in the organization, even though nobody actually looks at it anymore. This was exactly what happened to me at a junior and senior level over a ten-year period.

When I was a young financial manager in a Baxter division, the CFO asked me to gather some data for a report. I put the report together and showed it to my boss. The next month, I was moved into a different job. Ten years later, I became the CFO. As I was going through an enormous stack of reports in my inbox, near the top was the latest update of the report I had put together a decade earlier. I called the person who had prepared the report and told him, “I'm just really curious. Why do you put this report together every month?” He replied, “Well, the CFO wants to see this.”

I explained to him that, first, I was the CFO and, second, it was no longer necessary to prepare the report. Then I asked him, “So how long have you been preparing this report?”

“Ever since I replaced the guy who had the job before me,” he told me.

“Who did you replace?” I asked.

“A guy named Harry Kraemer,” he replied.

You can imagine the good laugh I got out of this one. The moral of the story is that there is an endless list of possible reports, with countless permutations. Unless you take the time to eliminate the ones you do not need, you will waste hours of your time and your teammates' time.

Measuring is important, but you need to be strategic and discerning about what you measure and why. You simply don't have enough time to review all the information, all the time. Successful organizations do not just generate and collect data. They turn data into information, and information into knowledge that they can use to make decisions. They do not get bogged down with data and making reports, but target the data they need to become knowledgeable and make informed decisions.

Speed is of the essence in business, and you need to be able to make decisions based on incomplete information—that's right, incomplete information. You also need to inject a sense of urgency into decision making, because there are many people in an organization who can give you reasons why you ought to delay the decision until tomorrow. My experience was always that unless you could give me a really good reason to wait, we were charging ahead. Whenever I encountered someone who wanted to delay a decision, I always asked what we did not know now that could significantly improve our ability to make a decision later. This was not a case of expediency for its own sake. Most of the time when you lose, it is not so much a result of making the wrong decision as it is waiting too long to make a decision.

A key principle attributed to Colin Powell is not to take action if the information you currently have gives you less than a 40 percent chance of success. At the same time, you cannot wait until you have enough facts to be 100 percent sure, because by that time, it is almost always too late.1 The reason people feel they need to have 100 percent of the information is that they are worried about making a mistake. I think this concern is overstated. If we have 40 percent of the information we need, we will probably choose the right direction. However, if it turns out that we are headed in the wrong direction, we will adjust. It may be as subtle as changing from north to northwest, but that's fairly easy to do if you are already moving in the first place. As soon as you have the necessary information, even if it is incomplete, get moving!

One of the best examples of a leader who made decisions and acted decisively on incomplete information was Lance Piccolo, an executive vice president at Baxter who went on to become CEO of Caremark. As a Marine and a football player, Lance developed a strong orientation toward action. Anytime one of us heard his favorite expression, “We're going to take that hill,” we knew we'd better get our boots on. There was no use trying to delay on the grounds of needing more data. Lance would tell us, “There were times as a Marine I was ordered to take a hill. The senior officer would say, ‘Piccolo, you took the wrong hill!’ But I would tell him, ‘We took it aggressively, sir!’” His point was well taken: gather data, transform data into information and knowledge, make a decision, and go. If you hesitate, you won't take the hill, and you could lose the battle—and the war.