DEALING WITH CHANGE

,If there is one thing you can count on, it is change. As a leader, you will face tremendous amounts of change, both within the organization and outside, such as new regulations, technology advances, and global economic conditions. That being said, the great majority of people in any organization, large or small, do not like change. Some find it unsettling, and for others it is downright scary. As a result, many people do whatever they can to avoid change. This approach is completely futile, however, because as the saying goes, the only constant in life is change. Things will change for you, your organization, across the industry, and in the global economic environment. As a leader, you will be far more effective if you improve your ability to accept and initiate change.

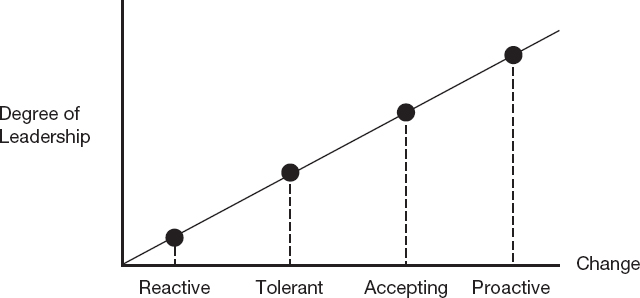

In your self-reflection, ask yourself how you respond to change. If you find change difficult or daunting, then admit it. Unless you know where you are starting, how can you know where you need and want to improve? Consider the graphic on page 173.

As you move from being reactive to becoming proactive, a greater degree of leadership is achieved.

Your reaction to change has a direct impact on how you lead and your effectiveness as a leader. As the graphic shows, being reactive limits leadership (as shown on the vertical axis), whereas being proactive expands it. Let's take a closer look. The first phase, as depicted in the graphic, is reactive, during which people who hate change hope that nothing happens. The ideal situation for them is a tomorrow that looks a lot like today. A leader who is reactive spends the majority of his time trying to duplicate what everybody else is doing. The degree of leadership displayed in this instance is minimal.

The next phase is tolerating change. In this situation, people would prefer not to deal with change, but are able to tolerate it when absolutely necessary. A leader who can tolerate change is somewhat more effective than one who is reactive, but her impact is still limited. A leader who only tolerates change does what she can to avoid it, but will adapt when she has no other alternative.

Those who can accept change, even though they are not very happy about it, are more effective than the first two groups because they can figure out a way to deal with what is happening. A leader who accepts change looks at the situation more positively and realizes that the organization will be better off.

Lastly, there is the proactive phase. Instead of only reacting to, tolerating, or accepting change grudgingly, the proactive leader is actually initiating it. A proactive attitude toward change enables leaders to be the most effective. The proactive leader isn't just riding the waves; he is out in the middle of the ocean creating them! Being the catalyst for change to which everyone else has to react requires the greatest degree of leadership. The proactive leader is comfortable with taking calculated risks and realizes that winning the game requires the team to get ahead of its competitors. The leader sees that proactively creating change is a great way for the organization to become a market leader.

Your attitude toward change will have a tremendous influence on how your team and the entire organization handle change. Keep in mind, however, that just because you are comfortable with change doesn't mean your team will automatically adopt the same attitude. If your team, department, or company is averse to change and taking risks, ask yourself why. Chances are, the answer lies in the collective memory of the team. Consider what happened to the last three people who took a significant risk at the company. If they were all fired, you probably have discovered the root of the problem. People are often reluctant to take a risk out of fear of what will happen if the desired results are not achieved.

The culture of an organization should allow failure to occur as long as lessons are learned, and as long as the failure occurs early enough in the process so as to minimize the time and money wasted. This thinking encourages a healthy attitude whereby risk is evaluated in the context of potential return. If the return you're pursuing outweighs the risks you're taking, then the trade-off is reasonable. No matter how thorough the analysis, however, you cannot completely eliminate risk. There is always a chance of failure; some unforeseen circumstance can derail even the best-thought-out project.

As a quantitative person, I found this type of thinking challenging at first. Perhaps it was my mathematics background; I liked the comfort of knowing that the answer was in the back of the book. I tackled the problem, solved the equation, and then checked to see if I was right or wrong. When it comes to taking risk and creating change, however, there is no guarantee of being right no matter how well prepared you are. The temptation is to try to increase your odds of success by gathering more data, but that tactic often is not effective. As we discussed in Chapter Ten, the longer you take to gather more data, the greater the likelihood that the opportunity will be lost—and often to a faster-moving competitor.

Another factor that impacts how people handle change is illustrated in the following equation: Change + Uncertainty = Chaos. We know there will be change; that is a given. Therefore, the less uncertainty you create, the less chaos that will result. Your priority as a leader is to reduce the amount of uncertainty that surrounds change. If you allow too much uncertainty, the only result you can expect is chaos.

Let's say that your company is going to acquire ABC Inc. Other than announcing that an acquisition is taking place, many organizations don't share much more information because management doesn't know the full scope of the changes and how they will impact everyone. As soon as they know, which could be months from now, they will inform everyone.

As the leader, you need to ask yourself, What are people going to do for all those months until they know the impact of the acquisition, especially with regard to whether or not they will have a job? The answer is simple: the understandable human response will be to speculate, discuss, gossip, and listen to the rumor mill. In the absence of authoritative information, they will rely on hearsay and conjecture—all of which adds up to more uncertainty, which results in chaos. By the time the acquisition of ABC Inc. is completed, 90 percent of the best people probably have left the company to take other jobs. Their departure decreases the effectiveness of the team, which will lessen the success of the acquisition and impair the integration of the two companies.

At Baxter, we made many acquisitions. Because I remembered the cube, I understood that what looked like a good deal to management could be a source of uncertainty for the rest of the team. Therefore, my approach was to identify the most important things on people's minds. To address those concerns, I would bring in the most appropriate people to study the issue and get an answer for the entire team as soon as possible. If it turned out that three months later we needed to reverse that decision, we would adjust and explain the reasons why.

To use an example, let's say that a company has been analyzing how to make its operations more efficient. As the leaders focus on three production plants in particular, they decide that one will close, one will definitely remain open, and one requires more analysis. As shown by our equation, for the leaders to prevent chaos, they must reduce uncertainty. This means they must tell people as much as they can. If there are unknowns, leaders need to tell people when they expect to have an answer. (As we said in Chapter Eight, you must tell people what you know, what you do not know, and when you will get back to them with an update. Communicate three times more frequently during difficult or uncertain times than when things are going well.)

In this example, the message to team members is that the Topeka plant is staying open; the plant in Baltimore is closing, but to minimize the impact, as many people as possible will be transferred to another facility in Washington, DC. No decision has been made as yet regarding the plant in Houston, because of several factors that need to be determined; a decision will be made in two weeks. Using this approach, the leaders ensure that everyone knows where things stand; speculation is minimized, and uncertainty will not run rampant to the point of creating chaos. More important, people will have confidence in what they are being told, which increases trust and loyalty to the organization.