While waiting in a city park to interview someone for this book, a nearby child played with Silly Putty and Legos at the same time. In my notepad I listed how many ideas the young boy, not more than five years old, came up with in 10 minutes. Sitting in the grass, he combined, modified, enhanced, tore apart, chewed on, licked, and buried various creations I'd never have imagined. His young mother, chatting on a phone while resting her morning coffee on the park bench, barely noticed the inventive creations her toddler unleashed on the world. After being chased away for making her nervous (an occupational risk of writers in parks), I wondered what happens to us, and what will happen to this boy, in adulthood. Why, as is popularly believed, do our creativity abilities decline, making ideas harder to find? Why aren't our conference rooms and board meetings as vibrant as childhood playgrounds and sandboxes?

If you ask psychologists and creativity researchers, they'll tell you that it's a myth: humans, young and old, are built for creative thinking. We've yet to find special creativity brain cells that die when you hit 35, or special hidden organs born only to the gifted that pass ideas to our minds. Many experts even discount genius, claiming that the amazing creations by Mozart or Picasso, for example, created their amazing works through ordinary means, exercising similar thinking processes to what we use to escape shopping mall parking lot mazes or improvise excuses when late for dinner.[106] Much like children, the people who earn the label creative are, as Howard Gardner explains in Frames of Mind, [107] "not bothered by inconsistencies, departures from convention, non-literalness…", and run with unusual ideas that most adults are too rigid, too arrogant, or too afraid to entertain.

The difference between creatives and others is more attitude and experience than nature. We survived hundreds of thousands of years not because of our sharp claws, teleportive talents, or regenerative limbs, but because our oversized brains adapt, adopt, and make use of what we have. If we weren't naturally creative and couldn't find ideas, humans would have died out long ago. A sufficiently motivated bear or lion can easily kill any man—even the scariest, meanest, all-pro NFL linebacker. However, given creative problems to solve, an average human being is hard to beat. We make tools, split atoms, and have more patents than the world's species' combined (but please don't tell the bears—they get pissy about patents). Our unique advantage on this planet is the inventive capacity of our minds. We even make tools for thought, like writing, so that when we find good ideas—such as how to tame and cage lions—we can pass that knowledge to future generations, giving them a head start.

But with the advance of civilization, creativity has moved to the sidelines. Idea reuse is so easy—in the form of products, machines, web sites, and services—that people go for years without finding ideas on their own. Modern businesses thrive on selling prepackaged meals, wardrobes, holidays, entertainments, and experiences, tempting people to buy convenience rather than make things themselves.[108] The need for craftsmen and artists, professional idea finders, has faded; more people than ever make livings in careers Lloyd Dobler would hate: selling, buying, and processing other things. [109] Even when charged to work with ideas, few adults can do so as easily as they could in their youth.

Einstein said "imagination is more important than knowledge," but you'd be hard-pressed to find schools or corporations that invest in people with those priorities. The systems of education and professional life, similar by design, push the idea-finding secrets of fun and play to the corners of our minds, training us out of our creativity. [110] We reward conformance of mind, not independent thought, in our systems—from school to college to the workplace to the home—yet we wonder why so few are willing to take creative risks. The truth is that we all have innate skills for solving problems and finding ideas: we've just lost our way.

Quick test: Name five new ways to change the world, or you will die!

Sorry, time's up. Fortunately, I can't kill anyone from this side of the book, and writers killing readers is bad business. But if I did honor the threat, you'd be dead. No one can come up with one big idea, much less five, that fast. As absurd as this paragraph is so far, it mirrors how adults often manage creative thinking: "be creative, and perfect, right now." Whenever ideas are needed because of a crisis or a change, there's a fire-drill call, an immediate demand. But rarely is the call met with sufficient resources— namely time—to mine those ideas. The bigger the challenge, the more time it will take to find ideas, but few remember this when criticizing ideas to death moments after they've been born.

Cynical idea-killing phrases like, "that never works," "we don't do that here," or "we tried that already" are common (see "The list of negative things innovators hear" in Chapter 4) and can easily make idea finding environments more like slaughterhouses than gardens. It's as if an idea knocks on the door, and someone answers waving an Uzi: "Go away! I'm looking for ideas." Ideas need nurturing and are grown, not manufactured, which suggests that idea shortages are self-inflicted. It doesn't take a genius to recognize that ideas will always be easier to find if they're not shot down on sight.

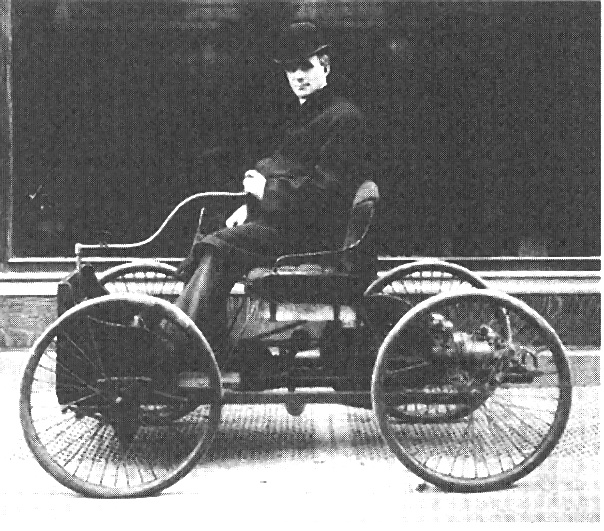

The myth that leads to this idea-destroying behavior is that good ideas will look the part when found. When Henry Ford made his first automobiles—awkward, smelly machines that stalled, broke down, and failed even the most generous comparisons to horses— people judged the superficial aspects, not the potential (see Figure 6-1). Everyone believes the future will come all at once in a neatly gift-wrapped package, as if Horse 2.0, whatever its incarnation, would make its first appearance with trumpets blaring and angels hovering above. The future never enters the present as a finished product, but that doesn't stop people from expecting it to arrive that way.

The idea of the computer mouse (see Figure 6-2) was equivalently weird and uninspiring to pre-PC age eyes ("Wow, a block of wood on a cord! The future is here!"). Evaluating new ideas flat out against the status quo is pointless. New ideas demand new perspectives, and it takes time to understand, much less judge, a point of view. Flip a world map or this book upside down, and at first it will feel bizarre. But wait. Observe for a few moments, and soon the new perspective will become comprehendible and possibly useful. However, that bizarre initial feeling tells you nothing about the value of the idea—it's an artifact of newness, not goodness or badness. This means using statements like "this hasn't been done before" or "that's too weird" alone to kill ideas is creative suicide: no new idea can pass that bar (see the upcoming sidebar "Idea killers").

[106] Robert W. Weisberg, Creativity: Beyond the Myth of Genius (W. H. Freeman, 1993).

[107] Howard Gardner, Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences (Basic Books, 1993).

[108] My position is not that everyone should make everything themselves, but that 1) everyone has the capacity to enjoy creating something, and 2) the temptation for convenience prevents many people from discovering what it is they like to make.

[109] Llyod Dobler is the main character of the film Say Anything, played by John Cusack. "I don't want to sell anything, buy anything, or process anything as a career. I don't want to sell anything bought or processed, or buy anything sold or processed, or process anything sold, bought, or processed, or repair anything sold, bought, or processed. You know, as a career, I don't want to do that." See http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0098258/quotes.

[110] See Neil Postman, The End of Education: Redefining the Value of School (Vintage, 1994) and Ken Robinson, Out of Our Minds: Learning to Be Creative (Capstone, 2001).