Chapter 3

Taking a Closer Look at Coeliac Disease

In This Chapter

![]() Looking at the frequency of coeliac disease

Looking at the frequency of coeliac disease

![]() Examining causes

Examining causes

![]() Reviewing the effects of coeliac disease in the body

Reviewing the effects of coeliac disease in the body

![]() Understanding the relationship between gluten and dermatitis herpetiformis

Understanding the relationship between gluten and dermatitis herpetiformis

![]() Looking into the future of treatments

Looking into the future of treatments

C oeliac disease is common, but hard to diagnose, because it mimics the symptoms of many other conditions. The word coeliac comes from a Greek word koiliakos, meaning ‘suffering in the bowels’. (Was that a heartfelt ‘oh, yeah’ from someone out there?)

Coeliac disease doesn’t have a cure, but it can be treated very effectively by diet and no medication is needed. Even on a gluten-free diet people with the disease remain sensitive to gluten for the rest of their lives. However, they no longer have the unpleasant and distressing symptoms that led to their diagnosis. Yet most people with the disease aren’t yet diagnosed.

So just how common is it? Well, since you asked, in this chapter, we cover this and other aspects of coeliac disease, including its causes and what the condition does to the body. We also look at the connection between gluten and dermatitis herpetiformis, and what research is being undertaken into coeliac disease.

Exposing One of the Most Common Genetic Diseases

Recent research indicates that as many as one in 80 Australians are affected by coeliac disease, and the prevalence may be as high as one in 60. Of those, fewer than one in five is currently diagnosed. Close relatives (parents, brothers, sisters and children) have about a 10 per cent chance of having or developing coeliac disease.

To put these numbers in perspective, coeliac disease is more common than Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease and cystic fibrosis combined. Table 3-1 shows how coeliac disease measures up.

People often wonder: If coeliac disease is so common, why don’t more people have it? They do! They just don’t know it yet (and may struggle through life never finding out what is wrong with them).

Table 3-1 Incidence of Common Genetic Diseases in Australia

Disease |

Estimated Number of People |

Type 1 diabetes |

940,000 ( |

Epilepsy |

735,000 |

Coeliac disease |

250,000 (Coeliac Australia) |

Crohn’s disease |

36,000 ( |

Parkinson’s disease |

25,000 ( |

Multiple sclerosis |

15,000 (Trish Multiple Sclerosis Research Foundation) |

Cystic fibrosis |

1 in 2,500 births |

Pinpointing Who Develops Coeliac Disease and Why

Doctors have no way to accurately predict who develops coeliac disease. What doctors do know is that you need at least three things in order to develop the condition:

- The genetic predisposition

- A diet that includes gluten

- An environmental trigger

Even if you have all three, you may never develop coeliac disease. You can say, though, that if you’re missing one of these three things, you won’t develop the disease. Coeliac disease affects most races and nationalities. Experts commonly believe the condition to be more prevalent in people with European or west Asian ancestry, but that distinction is diminishing as populations are becoming more diverse and intermingled. It is still uncommon in Australia among people of full Aboriginal descent and in the Oriental Asian population.

It’s in the genes

No-one knows all the genes that are involved in developing coeliac disease, but researchers do know of two key players: HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8. You don’t have to have both — just one will do — and DQ2 is the one seen most often in people with coeliac disease.

Approximately one-third of the general population has one or both of these genes, but of those who do, only about one in 30 goes on to develop coeliac disease. If you don’t have either gene, you have a 99.6 per cent chance of not developing coeliac disease. You can pretty well rule it out. But knowing that you have one or both of the genes still doesn’t tell you whether you’ll develop coeliac disease. So the gene test can’t diagnose coeliac disease; its main use is to rule out the possibility of coeliac disease.

Gluten is the guilty party

In the past, in certain places in the world none of the gluten-containing grains were ever eaten and so, as far as we know, coeliac disease was not found. In today’s world, it’s highly unlikely that a child could grow up without ever being exposed to wheat, rye, barley or oats. But if you never, ever ate gluten you wouldn’t develop coeliac disease.

Triggering coeliac disease through the environment

Coeliac disease isn’t dominant or recessive — it’s multifactorial; that is, both genetic and environmental factors are involved. Some of the environmental factors we know and some we don’t.

Some people have a pretty clear idea of when their coeliac disease was triggered, because in many cases they’re relatively healthy and then boom! Their symptoms seem to appear ‘out of the blue’ and they have no idea why. But doctors have no way of telling how long the disease has been active before symptoms are first noticed.

Environmental triggers can include

- Car accident or other physical injury

- Divorce, job loss, a death in the family, or other emotional trauma

- Illness, including gastroenteritis or rotavirus

- Pregnancy

- Surgery

Others show signs of coeliac disease in early childhood but it’s not diagnosed and they appear to recover during adolescence. Symptoms return in adulthood, gradually increasing in severity.

Understanding Coeliac Disease and What It Does to the Body

Coeliac disease is an autoimmune disease (a disease in which the immune system attacks the body) that’s activated when someone eats gluten. To help you understand exactly what damage is being done, we revisit high school biology, specifically focusing on the gastrointestinal tract.

How your guts are supposed to work

You’ve got guts, but do you know how they work? Skipping approximately dozens of important steps, we start our explanation in the upper part of the small intestine. The food has already been chewed, swallowed and passed through the stomach to the intestine.

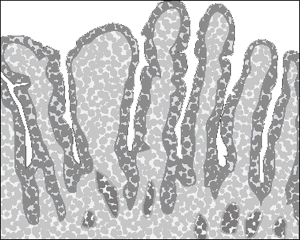

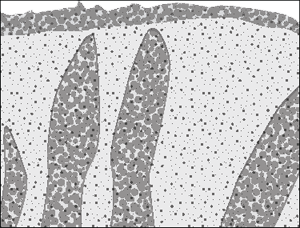

The small intestine is lined with numerous finger-like projections called villi, shown in Figure 3-1. A cross-section of a single villus at high magnification shows a covering layer of tall cells called enterocytes. With even greater magnification you see hundreds of minute, hairlike projections known as microvilli on the surface of each enterocyte, each packed with enzymes. The villi and microvilli create an enormous surface area for absorbing nutrients.

The lining of the small intestine is basically a solid wall. All the cells on the lining are joined together by tight junctions. When the body is ready to absorb the nutrients, these tight junctions open the space between cells and let the good stuff in — but keep the bigger bad stuff, like toxins, out.

How do the tight junctions know how far to open? They have a security guard named zonulin. Zonulin is a protein — it acts as a sort of nightclub bouncer, opening the tight junctions just enough to let the good stuff in but keep the harmful stuff out.

How your guts work with coeliac disease

Problems start when the food reaches the small intestine. The nutrients have been chopped into minuscule particles (amino acids and gluten peptides) that normally pass through the wall and enter tiny blood vessels for distribution around the body. But in a person with coeliac disease, these gluten peptides are actually toxic. Experts believe that the zonulin ‘security guard’ (refer to preceding section) may allow larger particles of gluten peptides to pass through the wall. In other words, coeliacs may have a degree of intestinal ‘leakiness’ and when the immune system checks out these peptides, it thinks they’re harmful. Some people refer to this as ‘leaky gut syndrome’, but the term has no medically agreed meaning.

The cells of the immune system attack gluten as if it was a viral or bacterial infection and in the process the surrounding tissues in the intestine are severely damaged. If an individual continues to eat gluten the attacks are relentless and the tissues don’t get a chance to recover. Over time, so much inflammation occurs that the finger-like villi are no longer fully exposed and the surface area appears to be flattened (see Figure 3-2). With far less surface area the intestine loses its ability to absorb nutrients — this is called ‘malabsorption’. That’s why you see nutritional deficiencies in undiagnosed coeliacs.

Because the food is just passing through the intestine without being absorbed the way it’s supposed to be, you sometimes see diarrhoea. But think about this: The small intestine is nearly seven metres long and the damage starts at the upper part — so you have lots of small intestine to compensate for the damaged part that’s not able to do its job. That means by the time you have diarrhoea, you’re usually a very sick puppy.

Armed with all these details, just think what a hit you’ll be at cocktail parties now that you can fascinate your friends with discussions of your villi, zonulin and leaky guts.

After diagnosis

A recent study in Melbourne looked at recovery in newly diagnosed coeliacs. After one year on a gluten-free diet they were given a repeat biopsy and blood tests. People who continued to eat some gluten did not improve. All of those who maintained a strict gluten-free diet showed good recovery, but only 50 per cent had a normal bowel at the end of the study. Individuals who had shown the most extensive damage at diagnosis had not improved as much as those with minor damage, suggesting that severe damage to the gut usually takes longer (up to two years) to recover. No real surprises there!

But here’s the interesting finding. Repeat blood tests showed that although antibody levels fell over time, half of those involved still had raised tTg (transglutaminase) and one in five still had raised EMA (endomysial antibodies), even though many of those people had shown full recovery in their biopsies. It seems that blood tests aren’t a reliable way to measure recovery of the gut or compliance to the gluten-free diet. The only way to be absolutely sure is to have another biopsy.

Your doctor may want to check that you don’t have a lactose intolerance — this can occur in newly diagnosed coeliacs as a result of damage to the gut. In most cases this disappears after a few months. Lactose-free dairy products are now easily available, or you can buy Lacteeze tablets from a pharmacist, which contain lactase, the enzyme you’re lacking. You need to see a dietitian to make sure you’re getting enough calcium in your diet.

At this point, having a DEXA scan to measure your bone mineral density is a good idea, even if you’re a young person or have no symptoms of osteoporosis. If a problem is apparent, the earlier you start treatment the better. You may be advised to increase your intake of calcium or take calcium and vitamin D supplements to protect against bone-density loss. Weight-bearing exercise is also very important in keeping your bones strong.

Recommendations from the Gastroenterological Society of Australia (GESA) to doctors for six-monthly follow-ups for the first year after diagnosis include:

- Calcium, phosphate, vitamin D, zinc, PTH test

- Coeliac serology

- Full blood count

- Iron, vitamin B12, folic acid test

- Liver function tests

- Thyroid function

Gastroenterologists generally like to do a follow-up biopsy after 12 months to check improvement in the small bowel. If strong improvement isn’t shown, you may be asked to see a dietitian to check that you’re not inadvertently eating gluten.

And if that’s not strong enough incentive for you, how about adding better wellbeing, improved vitality and mental function. Sounds good to us!

Scratching the Surface of Dermatitis Herpetiformis

Dermatitis herpetiformis (we refer to it as DH from now on) is a severe, itchy, blistering skin condition mainly affecting people of European descent. It’s slightly more common in males than females and usually occurs between the ages of 40 and 50, although it can turn up at any age. The cause of DH isn’t yet known, but both genetic and environmental factors are involved. Experts generally accept that DH is a distinctive form of coeliac disease, because 90 per cent of cases have the HLA-DQ2 gene and 10 per cent have the HLA-DQ8 gene found in coeliacs (we talk about these genes in the section ‘It’s in the genes’, earlier in the chapter). GH is less common than coeliac disease, with a prevalence of 1 in 10,000.

Usually, the rash starts as groups of red bumps with tiny blisters on top, but they itch so intensely that people sometimes scratch them to the point of opening the blisters, which then crust over. In some people the rash looks more like hives, located in one area; in others it looks more like pink, scaly dermatitis. The rash occurs commonly on the elbows, knees, bottom, back of the neck and in the hairline, eyebrows and scalp, but can also be on the face, trunk and other parts of the arms and legs. The rash also tends to appear symmetrically in these areas (equally on both sides of the body). Most people with DH don’t have any gastrointestinal symptoms, but research indicates that they will all have some degree of damage to the gut, as in coeliac disease.

To diagnose DH, doctors take a biopsy of the skin near the lesion. The process isn’t painful, because doctors can use a local anaesthetic to numb the site. They’re looking for an antibody called IgA (we talk more about IgA in Chapter 2) and if they see it, they make a diagnosis of DH.

Treatment is a strict gluten-free diet, but improvement takes some time. A medication called Dapsone may be prescribed to reduce the rash and relieve the itch. However, Dapsone doesn’t improve the damage to the intestines and so a gluten-free diet is also essential. Side effects from long-term use of Dapsone include a form of anaemia, chronic tiredness, depression, headaches and nerve damage, so your doctor will monitor your progress carefully. The rash flares up again if you eat foods containing gluten, or if you stop taking Dapsone before your gut has fully healed.

What Does the Future Hold For Coeliacs?

Over the past two decades, our understanding of why gluten is toxic for people with coeliac disease has increased dramatically. Doctors know that for gluten to become toxic it needs to be able to be absorbed into the body through the bowel to reach the immune system, where it triggers an abnormal reaction. This understanding has paved the way for designing new treatments that could either supplement the gluten-free diet, or potentially replace it altogether

Coeliac disease is now firmly on the research radar and some of the more innovative (and promising) new work is being done in Australia.

Research into coeliac disease fits into three broad categories. Firstly, studies are underway to trial medication for newly diagnosed coeliacs that will speed up the healing process in the bowel after diagnosis. Other research focuses on attempts to prevent gluten from entering the gut and causing damage. Finally, major research that began in Australia aims to restore the immune system to a normal state so it no longer reacts abnormally to gluten.

Healing the bowel

Researchers are looking at the use of medication to speed up the process of healing in the bowel in newly diagnosed coeliacs. Up until now, the only treatment for coeliac disease has been a lifelong gluten-free diet.

To speed up recovery, drugs that improve the rate of healing may be prescribed in the future. At the time of writing, researchers in Melbourne are studying whether a drug called Budesonide might be used for this purpose — specifically, settling inflammation in the gut quickly. Rapid healing of the bowel may reduce long-term health issues but a strict gluten-free diet will still be necessary to maintain the gut in good health.

Keeping the gluten out

Here are some of the options researchers are looking at to prevent gluten from entering the gut in people with coeliac disease:

- Genetically modified cereals: Some researchers are working on developing varieties of cereals that don’t contain the components that are toxic for coeliacs. However, since gluten is very complex and a number of toxic parts are found throughout the grain, developing safe gluten-free cereals remains challenging.

- Enzyme tablets: Several researchers are trialling enzymes called endo-peptidases or glutenases, which are said to break down the toxic sections of gluten protein that are usually resistant to natural digestion by the gut. These are reported to provide protection for tiny amounts of gluten and may be useful in providing an extra layer of protection against accidental ingestion of gluten. However, the results on this therapy option are not conclusive and are, therefore, not recommended until further research has confirmed their effectiveness.

- Zonulin inhibitors: In a gut inflamed by gluten, zonulin breaks down the ‘tight junctions’ that help to hold intestinal cells together. This leads to an increased passage of food proteins such as gluten across the bowel into the body (We cover this in more detail in the section ‘How your guts work with coeliac disease’, earlier in this chapter.) Some researchers are concentrating on developing zonulin inhibitors that will reduce gut ‘leakiness’ so no gluten can pass through. However, since research has shown gluten can also pass through the cells themselves, this may negate the effect of blocking zonulin. Trials to assess this approach are underway.

- Transglutaminase inhibitors: When gluten reaches the small bowel an enzyme called transglutaminase (tTG) modifies gluten by a process called deamidation. This makes the gluten more toxic to the immune system. Researchers are working on drugs that can block the effect of transglutaminase, so less toxic gluten is available to trigger the immune system. Since tTG is essential for many processes in the body, such as wound healing, inhibiting its function needs to be done very carefully. Drugs to do this are still a while off from clinical trials.

- Blockers: Once the gluten has been modified by transglutaminase (refer to preceding point), your immune system swings into action. Cells called antigen presenting cells (APCs) sample the environment and pick up gluten fragments that are then ‘presented’ to T cells. These activated T cells then orchestrate a damaging immune response, leading to your bowel wall becoming damaged. Research is focusing on the development of drugs that can block the interaction between the APC and the T cell; however, these are in the earliest stages of development.

Letting the gluten in safely

Research looking into changing the body so it no longer reacts abnormally to gluten focuses on the immune system, for this is where the real problem lies for coeliacs. Rather than preventing gluten from entering the gut, the emphasis is on convincing the immune system that gluten is not so bad after all. Restoring the immune system to a state where it tolerates gluten, as it does in people without coeliac disease, should allow people with coeliac disease to return to a normal diet altogether.

Amazingly, researchers in Brisbane have shown that changing the immune response to gluten in people with coeliac disease is possible — by infecting them with a type of parasite called a hookworm. Hookworms seem to alter immune processes in the bowel, and when people with coeliac disease eat gluten the usual damaging immune responses are lessened. This tells researchers that the abnormal immune response to gluten can be changed, even in people with coeliac disease.

Another approach is to use a desensitisation treatment that returns the immune system to one where gluten is tolerated. Research into a drug that might do this began in Melbourne, where researchers defined the key parts of gluten that cause disease. By using these key fragments in a ‘coeliac vaccine’, called Nexvax2, researchers hope to restore immune tolerance to gluten and allow people with coeliac disease to return to a normal diet and good health. Clinical trials of Nexvax2 are currently underway — go to www.ImmusanT.com for more information.

Coeliac disease has many names that all mean the same thing, including celiac disease (the American spelling), sprue, coeliac sprue, non-tropical sprue (not to be confused with tropical sprue), gluten-sensitive enteropathy and Gee-Herter disease.

Coeliac disease has many names that all mean the same thing, including celiac disease (the American spelling), sprue, coeliac sprue, non-tropical sprue (not to be confused with tropical sprue), gluten-sensitive enteropathy and Gee-Herter disease. Most newly diagnosed coeliacs notice an improvement in their health within weeks and sometimes days, but this is dependent on the length of time you’ve had active coeliac disease. Even though your bowel will take time to recover, your health usually bounces back pretty smartly.

Most newly diagnosed coeliacs notice an improvement in their health within weeks and sometimes days, but this is dependent on the length of time you’ve had active coeliac disease. Even though your bowel will take time to recover, your health usually bounces back pretty smartly.