Introduction to Project Risk and Cost Analysis

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

• Define the terms risk and risk management, upside and downside risk, pure and business risk.

• Describe the fundamental formula for pricing a risk.

• Identify the two ways to manage pure risk and the four ways to manage business risk.

• List the five steps in the project risk management process.

• Explain why it is necessary to update a risk management plan throughout the project lifecycle.

• Identify the three categories of risk management costs and provide examples of each.

Estimated timing for this chapter:

| Reading | 40 minutes |

| Exercises | 1 hour 30 minutes |

| Review Questions | 10 minutes |

| Total Time | 2 hours 20 minutes |

FUNDAMENTAL CONCEPTS OF RISK AND RISK MANAGEMENT

We often don’t—and can’t—be sure what’s actually going to happen. There is often more than one possibility. Depending on the likelihood and potential impact of these possibilities, some strategies increase your chances of good results. Understanding the potential environment and making choices are the essence of managing risk.

The goal of risk management is not to predict the future. The goal of risk management is to make decisions in the present. Risk and risk management are widely misunderstood, so it’s important to establish some fundamental concepts about the topic. In this section, we’ll identify and define common terms in project risk and cost analysis to provide a common basis going forward.

RISK DEFINED

There are a number of common definitions of risk:

• Merriam-Webster Dictionary: Possibility of loss or injury; a person or thing that is a specified hazard to an insurer.

• Princeton WordNet: a source of danger; a possibility of incurring loss or misfortune.

• Wikipedia: The deviation of one or more results of one or more future events from their expected value; the value may be positive or negative.

• Dictionary.com: Exposure to the chance of injury or loss; a hazard or dangerous chance.

• PMBOK® Guide: Risk is an uncertain event or condition that, if it occurs, has an effect on at least one project objective.

Most definitions of risk focus on the possibility of adverse events: loss, injury, or hazard. But risk-taking often has a positive connotation. Famed management theorist Peter Drucker argues, “To take risks is the essence of economic activity.” (Drucker, 125) successful risk-takers are often praised and lauded. If indeed risk is only about the negative, such praise is hard to understand.

Both the PMBOK Guide and Wikipedia acknowledge the more complicated truth: while risk certainly includes the possibility of adverse effects, it can also include the possibility of positive effects as well. Some 80% of businesses fail within five years, but the leaders of the remaining 20% may become very rich indeed.

What all the definitions agree upon, however, is that risk is about the uncertainty of future events. There is always a possibility that things can go wrong, but there is also a possibility of potential gain. Problems are in the here-and-now; the risks with which we are concerned may—or may not—occur.

The PMBOK Guide definition of risk limits the discussion to potential events that might affect project objectives. However, there is also the possibility of collateral damage (or benefit). For example, a project may successfully dispose of hazardous waste in a way that achieves its internal objectives and benefits the company, yet negative effects may land on the shoulders of other people.

Conversely, a project that is a failure on its own terms may provide secondary benefits. In 1968, 3M research scientist Dr. Spence Silver invented an unusual adhesive that did not stick very strongly. It was useless and the project was abandoned. It was not until 1974 that another 3M researcher, art Fry, had problems with bookmarks falling out of his hymnbook, and thought of the long-abandoned weak adhesive. The result, of course, was Post-It® notes.

For the purposes of our discussion, we’ll modify the PMBOK Guide definition slightly: Risk is an uncertain event or condition that if it occurs will have a significant impact, whether negative (downside risk) or positive (upside risk). Our definition is agnostic as to whether the risk must affect a project objective or something outside the official boundary of the project.

This implies two conditions: the uncertainty and the effect. Uncertainty is measured as a likelihood or probability of the event. Sometimes our knowledge of the probability is quite accurate; other times we have very little idea whether the event is likely to happen or not. Sometimes we know the effect; at other times the effect is itself uncertain. The effect of a car accident covers quite a range, from the trivial to the catastrophic. By comparison, a problem, because it’s something that has already happened, only contains an effect.

THE VALUE OF A RISK

The fundamental formula for pricing a risk is to multiply its probability of occurrence by the cost if it should occur, expressed as:

Risk = Probability × Impact

If there is one chance in ten that a risk event will cause you to lose $1,000, we say the value of the risk is 10% × $1,000, or $100. That implies that if you can avoid the risk at a cost of less than $100, there’s a presumption that this would be a good investment.

There’s more to a risk decision than that, of course. For example, what if the cost of getting rid of the risk is $101? should you pay the extra $1? What else could you do with that $100 if you chose to accept the risk instead? are you really sure that those numbers are accurate in the first place? What about the upside risk? If there’s a 90% chance you’ll make $2,000, a 10% chance of losing $1,000 may be a completely reasonable risk to take.

The base value of the risk isn’t necessarily the final value of the risk, because not all considerations lend themselves to being expressed in financial terms. However, the financial basis of any risk is certainly information worth knowing, and often influences the appropriate decision.

TYPES OF RISK

Downside risk, as we’ve established, is the likelihood of a negative outcome from an uncertain event or condition, and upside risk is the likelihood of a positive outcome.

• Pure risk (also known as insurable risk) is a risk situation that only has a negative outcome. If the negative outcome doesn’t happen, you don’t receive a benefit, but only avoid a loss. The possibility of your being in a car accident, for example, is a pure risk. If it doesn’t happen, your life continues the way it was; the best you can do is avoid the downside.

• Business risk, on the other hand, combines the possibility of positive and negative outcome in the same decision or event. If you buy stock, for example, there’s a possibility that the stock will increase in value, and a possibility that the stock will decrease in value.

Theoretically, there are also risks that are pure upside, with no cost or effort that needs to be invested to achieve the result, and no negative consequence (status quo) for failing to achieve them. These are normally considered outside the sphere of risk management thinking because there’s no real decision that must be made: they are the essence of “no-brainer.”

There are two basic ways to change the value of a risk: you can change the likelihood that it will happen, or you can change the impact or consequences if it does happen. To make it less likely that you’ll be in an accident, you can drive safely. Obeying the speed limit, being sober, paying attention, and keeping both hands on the wheel lower the chance of being in an accident. To make it less expensive to be in an accident, you can buy car insurance. (The total financial effect of an accident isn’t actually changed by the act of buying insurance. What changes is who signs the check.)

Pure risks have a cost if they occur, and there is normally a cost associated with reducing or eliminating them: there’s a cost of being in a car accident and there’s a cost associated with buying insurance. The risk mitigation cost is what you would need to spend (including the effort involved in improving your driving skill) to reduce the risk to an acceptable level. When you make decisions about risks, you are comparing the risk mitigation cost to the cost of simply accepting the risk—doing nothing about it unless the risk should actually occur.

In managing business risk, you have to consider the costs and benefits of both the upside and downside possibilities. To improve your outcome as a stock market investor, you can improve the potential outcome of your investments four ways:

• Reduce likelihood of negative outcomes. Pick safer stocks.

• Reduce impact of negative outcomes. Invest smaller amounts.

• Increase likelihood of positive outcomes. Pick stocks with the possibility of large gains.

• Increase impact of positive outcomes. Invest greater sums of money.

It will be obvious that any of these strategies taken to excess is inappropriate. Picking safer stocks and investing smaller amounts reduces the chance of positive outcomes as well as negative ones. Stocks with the potential of big gains often have uncertainty associated with them (or else the price would already have gone up), so larger investments increase the potential impact of losses.

Balancing upside and downside risk has elements of both art and science. As you can see, risk plays an important consideration in virtually every aspect of business and life. Indeed, virtually every conceivable management activity involves developing and executing risk management strategies. As Drucker continues, “While it is futile to try to eliminate risk, and questionable to try to minimize it, it is essential that the risks being taken must be the right risks.” (Drucker, 125)

Of course, figuring out which are the “right” risks and what to do about them isn’t so easy. Fortunately, there is the discipline of risk management. From its origins in the financial and insurance world, the art and science of identifying, analyzing, responding to, and acting on risk has developed into a robust and comprehensive set of constantly evolving tools and techniques.

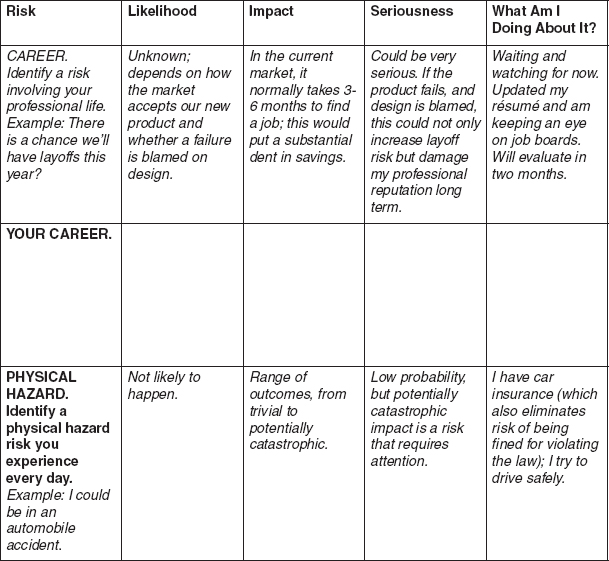

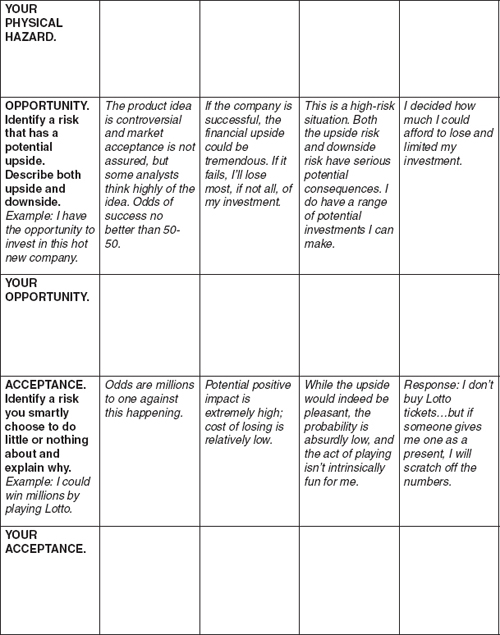

Exercise 1-1

Exercise 1-1

Managing Important Risks

We all practice risk management on a daily basis, whether we’re aware of it or not. In this exercise, you will identify important risks you are currently managing. For commentary on the exercise and your answers, see Answers to Exercises and Case Studies at the end of the course.

RISK MANAGEMENT DEFINED

As the name implies, risk management is the process of managing the risks in your environment. It can be formal or informal; it can be done well or poorly; it can use rigorous methodology or the notorious Wildly-aimed Guess (WAG) approach; you can act or you can fail to act.

Some disciplines inherently use more formal risk management techniques than others. Safety practices in engineering, quantitative risk analysis in finance, and quality control in business processes all involve the application of formal risk management tools. But risk management doesn’t always have to be rigorous and mathematical to be effective. Managing risks in, say, a sales office is likely to be a more informal process, but that doesn’t mean the resulting risk management is necessarily ineffective.

In the world of project management, risk management is an activity that parallels the other project processes. Because a project is a “temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique product, service, or result,” (PMBOK Guide, 1.2) it cannot possibly be devoid of risk: uncertainty is implicit in the definition. In the PMBOK model, the core risk management activities begin in the planning process, resulting in the development of a risk management plan. These activities are:

1. Identify the risks (risk identification)

2. Study the risks to understand their nature, probability, and impact (quantitative and qualitative risk analysis)

3. Decide what, if anything, is to be done about specific risks (risk response planning)

4. Integrate risk management decisions and actions into the project plan (risk management planning)

As the project gets underway, risk monitoring and control parallels project execution and other project monitoring and control activities. As the wave front of actual project knowledge moves forward in time, the risks of the project naturally evolve. There comes a point where a given risk can no longer happen: if the prototype passed its test, the risk that it might fail to do no longer exists.

On the other hand, if a risk occurs—thereby changing into a problem or opportunity—it may also trigger a domino effect on other risks, changing both their probabilities and impacts as well as your intended strategy. That means once is not enough when it comes to a risk management plan. Your initial plan needs constant review and updating as the risk profile of the project changes.

We suggest you keep a companion file to this course. Use it to hold your notes and any documents or forms from the text that will be helpful as you work through the chapters. Please access www.amaselfstudy.org/go/Project Risk for a list of documents that can be downloaded.

Exercise 1-2

Exercise 1-2

Your Current Risk Management Process

In this exercise, your goal is to describe the risk management process that currently exists with respect to the projects for which you are responsible, either as a manager or a participant.

1. Does your organization or department have a formal requirement for risk management planning on projects? Yes____ No____

2. Describe the formal requirement if one exists. Specify whether all projects are included, or whether there is a minimum project size for the requirement. If there’s a written standard, add that to the companion file of notes and documents you will keep with this self-study course.

3. If there is no formal risk management policy or process (or if it’s not well followed in practice), how are risks currently managed on your projects?

4. What works well about the way risks are currently managed on your projects?

5. In what ways could your project risk management be improved?

COST ANALYSIS AND RISK MANAGEMENT PLANNING

The actual cost of the project, as we all know, is not always or necessarily the cost originally planned or intended. Whether particular risks occur or don’t occur has a dramatic effect on the cost. And, as you’ve seen, responding to risk also has costs.

We’ve described the basic formula for valuing a risk. The cost of responding to risk falls into three basic categories:

• Risk management infrastructure. The cost of developing policies and programs, training people in their use, recording and tracking risk data, improving risk management performance. These costs are usually not charged directly to your project except as company overhead.

• Project risk management. The portion of project resources spent on identifying, analyzing, strategizing, and tracking risks; developing risk plans and reports; developing risk metrics.

• Specific risk mitigation costs. The costs associated with responding to individual risks.

Straightforward cost analysis is easier to perform when numbers are known and stable. How much you spent last year is a matter of record; what you will spend next year is subject to change. The cost of responding to risk involves actual expenditures. The value of the unmanaged risk, however, is best expressed as a range of probabilities. You don’t know what will actually happen. And yet it’s often incumbent upon you to come up with numbers that have some reasonable basis in reality.

As noted earlier, financial and statistical analysis is not necessarily the sole or always even the primary basis on which a given decision is made. That is not to say the numbers are ever inconsequential or irrelevant. Importantly, numbers change over time, hinting at trends or outcomes that may help you respond early when plans need adjusting. Risk management needs to be an ongoing process throughout the entire project life cycle.

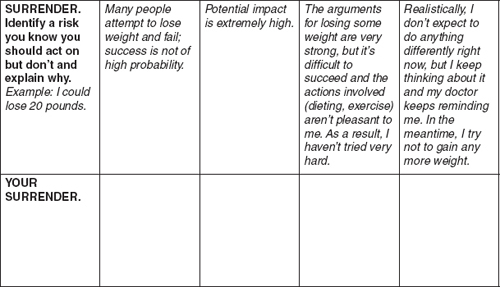

Exercise 1-3

Exercise 1-3

What You Spend on Risk Management

In this exercise, you will develop a rough estimate of how much of your project budget currently goes toward risk management activities.

RISK MANAGEMENT INFRASTRUCTURE

| Case | Estimated Cost | Charged to Your Project? |

| Example: Training course in risk management with outside vendor | $1000/participant for two-day workshop; 300 people trained | No |

| TOTAL COST | Value of your project as a percent of company revenue | Total cost × % project value = Amount attributable to your project |

| Case | Estimated Cost | Identified as Risk Management expense? |

| Example: Write and develop a risk management plan | 3 meetings attended by 5 people, average length 90 minutes, plus 15 hours writing time, at roughly $200/hour = $7500 | No; considered part of general planning budget |

| TOTAL COST | AMOUNT IDENTIFIED AS RISK MANAGEMENT |

SPECIFIC RISK MITIGATION COSTS

| Risk Being Mitigated | Estimated Cost | Identified as Risk Management Expense? |

| Example: Risk that the DigiWigit® prototype will be damaged in transit | Need to fabricate special insulated shipping case to ensure prototype is protected; cost $15,000 | No; shipping container cost built into original price and charged to customer |

| TOTAL COST | AMOUNT IDENTIFIED AS RISK MANAGEMENT |

TOTAL INVESTMENT IN RISK MANAGEMENT

| Infrastructure costs attributable to your project | $/£/€/¥ |

| Project risk management costs | $/£/€/¥ |

| Specific risk mitigation costs | $/£/€/¥ |

| TOTAL | $/£/€/¥ |

| Less costs charged officially to risk management | $/£/€/¥ |

| Costs not listed as risk management | $/£/€/¥ |

Risk is an uncertain event or condition that if it occurs will have a significant impact, whether negative (downside risk) or positive (upside risk). Risks may affect project objectives, or they may have an impact that falls outside the official boundary of the project.

The fundamental formula for pricing a risk is to multiply its probability of occurrence by the cost if it should occur, expressed as:

Risk = Probability × Impact

If the cost of dealing with the risk is significantly less than the price of the risk, there is a strong business case for action. If the cost is higher, action may still be appropriate, but additional justification is normally required.

In the real world, exact information on probability and impact is not always available or accurate. Factors other than financial analysis may enter into the decision. Still, the basic price of a risk is important information to support decision-making.

Downside risk is the likelihood of a negative outcome from an uncertain event or condition, and upside risk is the likelihood of a positive outcome.

Pure risk (also known as insurable risk) is a risk situation that only has a negative outcome. Business risk combines the possibility of positive and negative outcome in the same decision.

The two basic ways to change the value of a risk are to change the likelihood it will happen, or to chance the impact or consequences if it does happen. There is often a cost associated with changing a risk, so decision-makers must always consider those costs in comparison to the value of the risk. Not all risks require—or warrant—action.

When you consider a business risk, you must consider probability and impact of both the upside and downside elements in order to reach a balanced decision. Sometimes it may be wise to accept an increased risk of loss in exchange for a substantially increased risk of gain.

Risk management is the process of managing the risks in your environment, whether it is done as a formal, systematic process or not. Different disciplines, such as engineering, finance, and project management, have their own specific tools and approaches to risk management.

In project management, risk management is an activity that parallels the other project processes. Because a project is a “temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique product, service, or result,” (PMBOK Guide, 1.2), uncertainty and risk are always present.

In the PMBOK model, the core risk management activities begin in the planning process, resulting in the development of a risk management plan. These activities are:

1. Identify the risks (risk identification).

2. Study the risks to understand their nature, probability, and impact (qualitative and quantitative risk analysis).

3. Decide what, if anything, is to be done about specific risks (risk response planning).

4. Integrate risk management decisions and actions into the project plan (risk management planning).

5. Risk monitoring and control parallels project execution and other project monitoring and control activities. Risks change as the project moves forward in time, meaning that your initial plan needs constant review and updating as the risk profile of the project changes.

There are three basic categories of costs in dealing with risks:

• Risk management infrastructure. Organizational expenditures on risk management

• Project risk management. Costs of risk management processes on your project

• Specific risk mitigation costs. The costs associated with responding to individual risks

In risk management, you have strict limits on the knowledge available to you. Nevertheless, there are many tools that can help you manage and prosper even in the face of the unforeseen and unforeseeable.

INSTRUCTIONS: Here is the first set of review questions in this course. Answering the questions following each chapter will give you a chance to check your comprehension of the concepts as they are presented and will reinforce your understanding of them.

As you can see below, the answer to each numbered question is printed to the side of the question. Before beginning, you should conceal the answers by placing a sheet of paper over the answers as you work down the page. Then read and answer each question. Compare your answers with those given. For any questions you answer incorrectly, make an effort to understand why the answer given is the correct one. You may find it helpful to turn back to the appropriate section of the chapter and review the material of which you were unsure. At any rate, be sure you understand all the review questions before going on to the next chapter.

1. The cost of training staff members in risk management is an example of:

(a) specific risk mitigation cost.

(b) project risk management cost.

(c) risk management infrastructure cost.

(d) training in risk management cost.

1. (c)

2. For the purposes of risk management, risk is defined as:

(a) an uncertain event or condition that if it occurs will have a significant impact.

(b) a hazard or bad thing that might happen.

(c) a problem or situation you are currently experiencing.

(d) something that only affects the project on which you are working.

2. (a)

3. If there is a 20% chance of a price increase on a key project component that will increase your total cost by $10,000, the value of the risk is:

(a) $10,000

(b) $1,000

(c) $20,000

(d) $2,000

3. (d)

4. The activity of risk monitoring and control happens:

(a) during the project planning process.

(b) in parallel with project execution and other monitoring and control activities.

(c) throughout the project from initiation through closeout.

(d) at the weekly project status meeting.

4. (b)

5. Integrating risk management decisions and actions into the plan and other project management process is known as risk.

(a) response planning.

(b) management planning.

(c) analysis.

(d) identification.

5. (b)

Review Questions

Review Questions