Qualitative Risk Analysis

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

• Define common terms and concepts in risk analysis, including qualitative risk analysis, quantitative risk analysis, risk triage, and filtering.

• Identify appropriate risk categories to organize identified risks for further action.

• Use a filtering process to perform risk triage, sorting risks according to priority, urgency, ownership, and solvability.

• Implement a variety of qualitative concepts and techniques, including cause-and-effect diagramming to analyze impact, assessment of non-numerical factors in determining risk probability, identification of proper risk ownership, and the mechanism for transferring risks.

• Apply risk triage and other processes to confirm that risks have been correctly identified and categorized.

Estimated timing for this chapter:

| Reading | 40 minutes |

| Exercises | 50 minutes |

| Review Questions | 10 minutes |

| Total Time | 1 hour 40 minutes |

INTRODUCTION TO RISK ANALYSIS

In between deciding what the risks actually are and deciding what, if anything, you plan to do about them, comes risk analysis—the process of studying the risks to measure and define their probability, impact, and other characteristics. Armed with improved understanding, you can separate important risks from trivial ones and identify the opportunities you have to influence our risk environment in the right direction.

There are many different techniques used in risk analysis. Some are specific to a given industry or technical area. You don’t normally need a systems engineering risk assessment for a marketing plan, nor are the tools of financial risk analysis generally of primary value in determining whether the shop floor is safe. This self-study course will focus on the tools most commonly used and those with widest application. Depending on your industry, profession, and circumstances, you may want to explore a certain set of tools in much greater depth.

In general, risk analysis techniques fall into two groups. The PMBOK Guide (11.3, 11.4) defines them as follows:

• Qualitative risk analysis is the process of prioritizing risks for further analysis by assessing and combining their probability of occurrence and impact.

• Quantitative risk analysis is the process of numerically analyzing the effect of identified risks on overall project objectives.

Quantitative risk analysis as a process normally follows qualitative risk analysis, but the PMBOK Guide observes that, in some cases, quantitative risk analysis may not be required to develop effective risk responses. In certain categories of projects, quantitative tools may be used first, with qualitative analysis filling in the gaps. What’s important is that you use these processes and tools in the order and sequence they make most sense to you.

Qualitative Risk Analysis

When we performed risk identification in the last chapter, we decided to lean in favor of including risks rather than excluding them. Our risk register, therefore, includes a number of risks that fall below the reasonable threshold requiring response.

In qualitative risk analysis, we define the characteristics of the risk in more detail. We gather additional information. We rate the relative importance of the risk in terms of probability and impact—without, in many cases, being able to put specific numbers to those values.

Qualitative risk analysis accomplishes the following:

• By defining and assessing probability and impact, even in general terms, it ranks the relative importance of the identified risks to the project, the organization, and to specific stakeholders, enabling resources to be focused where they’ll achieve the most benefit.

• By classifying risks into categories, it helps reveal potential common causes and vulnerability areas where action can be highly productive, and ensures risks are routed to the proper owners and managed properly.

• By defining risk characteristics and potential common causes, it provides the basis for effective risk response planning.

Quantitative Risk Analysis

Quantitative risk analysis, as previously noted, is the process of numerically analyzing the effect of identified risks on overall project objectives. As the name “quantitative” implies, the key word in this definition is “numerically.” Quantitative risk analysis is classical risk analysis, the probability-based tools developed to assess risk in financial instruments such as insurance.

Quantitative risk analysis tools exist in many disciplines from finance to nuclear engineering. Any field in which it’s possible to calculate the likelihood of certain events based on either theoretical or actual probability uses quantitative analysis. (Theoretical probability is saying the chance of flipping heads is 1 in 2, because there are only two outcomes. Actual probability is flipping the coin a few hundred times and reporting the result.)

If you’re in a field with few available numbers to crunch, your opportunity to use quantitative risk analysis is limited, but you may be surprised by how many numbers you can find if you look hard enough—and what you can do with them if you find them.

Certain advanced project management techniques such as the Program Evaluation and Review Technique (PERT) and Monte carlo simulations have application to quantitative risk management, as you’ll learn in upcoming chapters. Other common analysis tools we’ll cover include expected monetary value (EMv), sensitivity analysis, and decision trees.

Quantitative risk analysis accomplishes the following:

• By analyzing the range of outcomes and their associated costs, it provides decision-makers with the data to establish reserves, set confidence levels, and identify whether the overall project is in line with stakeholder risk tolerances.

• By simulation and probability analysis, it provides an estimate of the likelihood of achieving a given set of time and cost objectives.

• By developing detailed numerical insights into risk characteristics, it refines the prioritization of risks and ensures that risk responses are cost effective and appropriate.

QUALITATIVE RISK ANALYSIS

In qualitative risk analysis, you sort the risks from the risk register based on their probability and impact, and then route them for further action. For any given risk, there are really only three choices: accept the risk, transfer it to someone else, or do something about it.

Accept the risk. When you accept a risk, you don’t do anything further about it unless it occurs. If it occurs, you may take some remedial action, or you may simply absorb whatever it does to you.

Transfer the risk to someone else. some risks aren’t yours. They may belong to the customer, to someone higher up in the organization, or to someone with specific authority or expertise. You do have the responsibility for making sure that the correct risk owner is aware of the risk. You often need to follow up and monitor their risk responses.

Do something about the risk. For now, this means that you put the risk in a stack with other risks requiring action. Some risks are so urgent you need to move them to the head of the line and start working on them now. Others can wait until you start your risk response planning process, which follows risk analysis.

If you’ve ever been in a hospital emergency room—or, for that matter, watched an episode of M*A*s*H—you know about triage, a formal method of prioritizing medical patients based on the severity of the situation and what can be done about it. Qualitative risk analysis is, in a fundamental sense, a triage approach to risks. Before you can act, you have to sort.

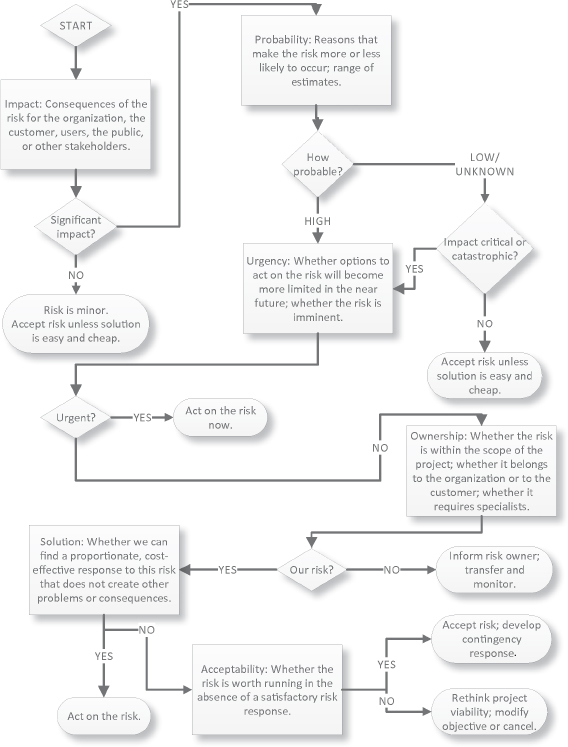

The project management process that accomplishes this is known as filtering. Your goal is to filter the risks on the project so that the top risks are singled out for action. Exhibit 3-1 outlines the filtering process as a flowchart, and the copy that follows describes the action steps in more detail.

Start

Take each risk from the risk register, and go through the process one risk at a time. Update the risk register based on the result of the filtering process; record the outcome on the risk register—even for risks that will go no further. This is an important step, to make sure that no risk is inadvertently overlooked.

Impact

You wrote down a description of the impact when you filled out the original entry in the risk register. Now it’s time to revisit that statement and amplify it.

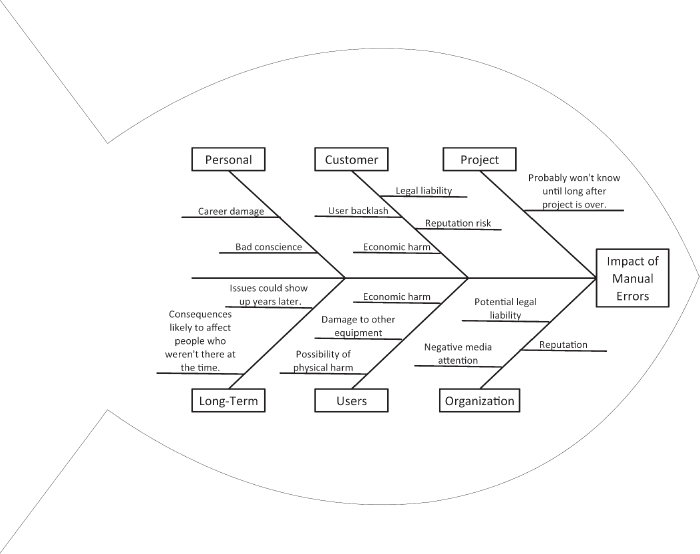

First, make sure you’ve considered all the potential areas in which the risk impact may occur. In risk identification, you encountered the cause-and-effect diagram (Exhibit 2-9). You can use the same tool to great effect in risk analysis. Let’s revisit the risk of tech manual errors, introduced in Exhibit 2-5. Here’s the statement of risk:

“If the manual contains errors, the customer may not be able to maintain and repair the equipment correctly and in extreme cases could suffer significant losses as a result of our errors.”

Here are six categories of potential impact for this particular risk. Don’t forget to add opportunities as well as threats. Often, the impact contains both. Exhibit 3-2 shows the cause-and-effect diagram.

• Project risks. Risks to the project and its objectives, primarily to the project’s constraints of time, cost, and performance.

• Organizational risks. Risks to the organization sponsoring or managing the project. Could include such factors as reputational or business consequences, legal exposure, marketing issues, media exposure.

• Customer risks. Risks to the customer and the customer’s organization.

• User risks. Risks to the end user of the product or service, including physical risks, economic risks, or other factors.

• Personal risks. Risk to you and your team members, such as continued employment, consideration for promotion or advancement, chance of getting other projects, effects on career or family.

• Long-term risks. Risks that are likely to outlast the life cycle of the project, the product, or the service.

Obviously, a risk that carries with it legal liability and the chance of physically harming others is a serious risk and one that requires appropriate action. But notice how the impact falls out. Its effects are extremely unbalanced. The project itself is hardly affected at all. It might be years before the consequences of errors in the tech manual come to light.

The customer and the users are exposed to the greatest share of the impact. Depending on the standards for legal liability or warranty claims, they may be able to transfer some part of those costs to the organization. The danger here is not so much that an unscrupulous project team will take the easy way out (though that has been known to happen), but that human nature puts our focus on dangers that affect us most immediately. When the impact falls outside the sphere of the project, it sometimes also falls through the cracks. That’s why this kind of risk assessment is so important.

In Exercise 3-1, you’ll take one of the statements of risk you wrote in Exercise 2-1, and give it the same treatment.

Exercise 3-1

Exercise 3-1

Cause-and-Effect Diagram

Take one of the three statements of risk you wrote in Exercise 2-1, and enter it into the “Risk Statement” box. Identify potential consequences of the event (both opportunities and threats), considering all six areas. You may not find meaningful impact in all six, but make sure you look at all of them carefully.

If the overall impact of the risk is not significant, then it may be sensible to accept the risk, unless the solution is easy and cheap. If the overall impact of the risk is significant, however, move to the next item on the list.

Probability

What (if anything) makes you believe this risk event may actually happen to your project? There are any number of potential reasons to believe a given event is more likely to occur. Consider the list of questions in Exhibit 3-3 as they apply to a particular risk. (The exhibit provides space for you to follow along, using either a risk from one of your own projects or continuing with the risk you used in the previous exercise.)

Sometimes you can arrive at a reasonable judgment that a given risk is low or high in probability, and other times there simply isn’t enough data to hazard a reasonable guess. Since we’ve already established that the impact is significant (otherwise, we’d have accepted the minor risk), risks of low or unknown probability and no greater than moderate impact are good candidates for acceptance unless, as before, the solution is easy and cheap. Low or unknown probability combined with serious impact, however, is normally worthy of further attention.

Urgency

Some risks just can’t wait. What really matters isn’t the timing of the risk event itself, but how fast any potential solutions may become unusable. In the previous example, we discussed reviewing the manual prior to publication to catch any errors. Notice that you can only do this up until the time you ship the manual to the customer. After that, it’s too late.

If the only, best, or cheapest solution is about to expire, or if the risk event is imminent, you don’t have time to take the risk through the rest of the process. Assign the risk to a risk owner or manager (it may be you), and get started on it without waiting for all the rest of the qualitative and quantitative analysis results to come in.

Ownership

Some risks are very serious, but that doesn’t automatically mean they’re yours. If the failure of your project could result in the bankruptcy of your organization, it’s the prerogative of senior management, not you, to determine whether the risk is worth running. If the customer signs a cost-plus contract for development, the customer owns the risk that the project will go over budget.

As we’ve mentioned, risk specialists exist in organizations to handle specific categories. If you’re an engineer, you probably aren’t the right person to manage legal risks on the project; if you’re a lawyer, you probably aren’t the right person to manage risks in systems engineering. As the project manager, you still have responsibility for risks that are not appropriate for you to manage. You should:

• Identify risks in all areas, not just inside the project boundaries.

• Gather basic information about these risks.

Probability Boosters

| Question | Example | Your Risk |

What’s the statement of risk? |

If the manual contains errors, the customer may not be able to maintain and repair the equipment correctly, and in extreme cases could suffer significant losses as a result of our errors. |

|

Has this ever happened before, either in our experience or in the experience of others? |

We’ve discovered minor typographical errors in published manuals, but nothing of significance. This is at least partially because we already do a lot of checking to keep serious errors out of the product. Major mistakes have, however, been known to happen elsewhere, and the consequences have in some cases been very severe. |

|

Are there any circumstances or conditions that would make this risk more likely to happen? Are these circumstances or conditions present on this project? |

The most likely reason for such an error occurring in the first place would be late-project engineering and design changes not being properly documented, so that manuals reflected out-of-date information. We do not currently see this happening, but if it does, we will revise our probability for this risk upward. |

|

Is this risk linked to other risks in the project environment? |

Yes. A major late-project engineering or design change normally increases risk throughout the rest of the project. If such an event happens, a number of project assumptions will be called into question and a comprehensive risk reassessment may be in order, especially if deadline remains the same and cost pressures are also high. |

|

Conclusion |

Probability of a major error is low in absolute terms, but high enough that our current review and quality control process should be continued. |

• Route risks to their proper risk owners, and provide relevant documentation.

• Support risk owners with information and technical advice.

• Review proposed risk responses for secondary impact on other project objectives.

• Integrate actions of risk owners into your project plan.

• Monitor risk responses and advise risk owners of trends and results.

While it’s usually appropriate (if not required) that you are deferential to risk owners outside your project, remember that risk owners tend to focus on their risk areas and may not always be in tune with the bigger picture. Try to accommodate the needs of risk owners as much as possible, but if you can’t and if the stakes are high enough, it may be appropriate to escalate the decision to a higher level of management.

Solution

So far, we’ve identified the following categories of risks:

• Risks without significant impact. You will probably end up accepting the majority of these risks unless the solution is easy and cheap.

• Risks with low probability and only moderate impact. You will also end up accepting the majority of these risks unless the solution is easy and cheap.

• Risks that require urgent response. Those risks are removed from the rest of the process and assigned to a person or team for immediate action.

• Risks that belong to someone else. You should route these risks and associated information to the proper risk owner, respond to the instructions and requirements provided by the risk owner, and monitor the risk.

This leaves a final category: risks that are serious in impact, at least moderately high in probability (if unlikely to happen, the impact is very serious indeed), and that belong to you.

The next question, naturally, becomes what (if anything) can you do about it? For now, it’s not necessary to come up with a detailed point-by-point action strategy, but to concern yourself with the general question. A risk is solvable if the response is proportional, cost-effective, and doesn’t create major secondary problems or negative consequences. If it appears to be solvable, move it into the stack of risks requiring further analysis and action.

Acceptability

It may be apparent from the beginning that there is no way to bring a particular risk down to an acceptable level. There may be some unavoidable dangers, or factors you can’t do anything about. Risk is a fact of life.

As mentioned earlier, accepting minor risks can be perfectly appropriate and sensible. When you’re confronted with a major risk outside your control, it’s not so simple. Ultimately, you have two choices:

1. Accept the risk and prepare a contingency response if possible.

2. Rethink the viability of the project, which may involve changing the objectives or cancelling the project.

This decision often doesn’t belong to the project manager, but is the province of higher levels of management or the customer. If that’s the case, treat it like an ownership issue, and make sure the risk, options, and supporting documentation are routed to the appropriate decision-maker.

RISK TRIAGE AND OTHER RISK ANALYSIS PROCESSES

It’s worth repeating that filtering your risks is only the first step in risk analysis. By grouping your risks into various action stacks, you can route risks to their proper owners, identify low priority risks requiring little or no action, and focus your attention on the subset of high risks that fall within your purview.

There isn’t a clear, bright line that separates risk triage (filtering) from qualitative or quantitative risk analysis processes. When answering the questions on the flowchart from Exhibit 3-1, you often need to apply certain of these tools even in your initial screening. Given also that your initial knowledge of risks may be incomplete, you also need to verify that your pile of low-ranking risks doesn’t accidentally end up including one or more risks deserving more serious attention.

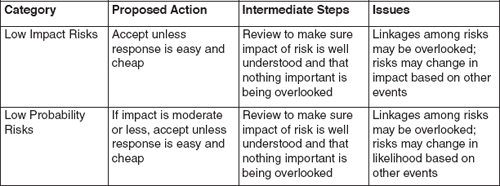

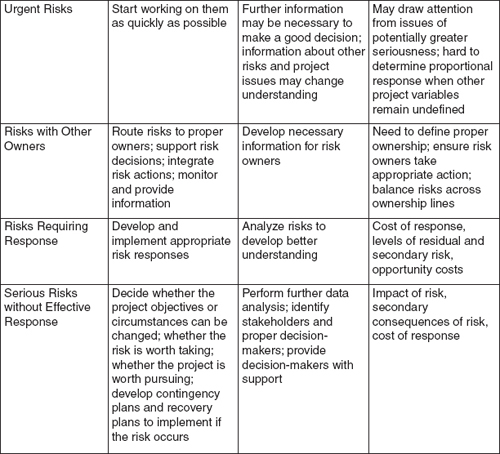

Exhibit 3-4 summarizes risk triage categories and next steps.

In between deciding what the risks actually are and deciding what, if anything, you plan to do about them, comes risk analysis, the process of studying the risks to measure and define their probability, impact, and other characteristics. In general, risk analysis techniques fall into two groups:

• Qualitative risk analysis is the process of prioritizing risks for further analysis by assessing and combining their probability of occurrence and impact.

• Quantitative risk analysis is the process of numerically analyzing the effect of identified risks on overall project objectives.

Not every risk requires both kinds of analysis. Although it is most common to perform qualitative risk analysis first and quantitative risk analysis second, situations vary.

Qualitative risk analysis begins as risk triage: a filtering process in which you sort risks by category, threat level, and ownership. You define the characteristics of the risk in more detail. You gather additional information. You rate the relative importance of the risk in terms of probability and impact—without, in many cases, being able to put specific numbers to those values.

Your basic choices about a given risk are to accept the risk, transfer the risk to someone else, or to do something about the risk. To make a decision about each risk, ask yourself a series of questions.

1. Is the impact significant? If not, consider accepting the risk unless the solution is easy and cheap.

2. Is the probability high? If not, consider accepting the risk unless the impact is very high.

3. Do we need to act immediately? If so, assign the risk to a person or team and get to work.

4. Is the risk ours? If the risk owner is outside the project team, route the risk (and relevant information) to the proper owner, and monitor the results.

5. can we do anything about this risk? If there’s a potential solution that’s appropriate, we are likely to implement it.

6. Is the risk worth taking? If there’s no potential solution, or if significant risk remains even after you’ve done what you can, you may choose to accept the risk, or it may be appropriate to modify or even cancel the project.

In the risk triage stage, you shouldn’t normally dig too deeply into risks or their solutions, but focus instead on sorting them into piles requiring different actions. In every case, it’s a good idea to review what you’ve done, because it’s all too likely that some risks have ended up in the wrong pile.

1. In performing risk analysis, the correct sequence is to:

(a) perform risk triage, qualitative risk analysis, and quantitative risk analysis in that order.

(b) apply qualitative and quantitative risk analysis tools simultaneously.

(c) apply quantitative risk analysis tools on every risk.

(d) use qualitative and quantitative risk analysis tools in the order that is appropriate for your project.

1. (d)

2. Factors such as reputation risk, business consequences, legal exposure, and unfavorable publicity are considered to be:

(a) project risks.

(b) customer risks.

(c) organizational risks.

(d) personal risks.

2. (c)

3. If a risk does not properly fall under the jurisdiction of the project manager or the project team, what should you do?

(a) Transfer the risk to the proper risk owner and monitor the risk.

(b) Take action if the risk is serious and consequences to the project are significant.

(c) Accept that the risk is not your business, and focus your attention elsewhere.

(d) Escalate any adverse decision to higher management.

3. (a)

4. The purpose of qualitative risk analysis is to:

(a) analyze numerically the effect of identified risks on project objectives.

(b) identify pure risks on projects.

(c) ensure all identified risks are fully analyzed and acted upon.

(d) analyze risks for probability and impact.

4. (d)

5. Advanced project management techniques such as PERT and the Earned value Method are useful in performing:

(a) qualitative risk analysis.

(b) quantitative risk analysis.

(c) risk triage and filtering.

(d) qualitative risk identification.

5. (b)

xhibit 3-1

xhibit 3-1

Review Questions

Review Questions