Risk Identification

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

• Describe the process of risk identification on projects.

• Create and populate a risk register.

• Examine project requirements, goals, conditions, and circumstances to identify risks.

• Determine whether a particular risk belongs to the project or is being sufficiently managed elsewhere.

• Write a statement of risk in the “condition and consequence” format.

• Apply a variety of tools and techniques to systematically identify and reduce project risk, including document review, standard and negative brainstorming, cause-and-effect diagramming and SWOT analysis, and checklists.

Estimated timing for this chapter:

| Reading | 55 minutes |

| Exercises | 1 hour 10 minutes |

| Review Questions | 10 minutes |

| Total Time | 2 hours 15 minutes |

IDENTIFYING RISKS

What, exactly, are you worried about?

Figuring that out is the process known as risk identification: listing the risks that give us potential concern. That includes business as well as pure risks, of course. We’re concerned with downside risks because of the negative impact; we’re concerned with upside risk because we’d really like to reap the benefits. We need to balance the level of risk and the level of response.

It’s not always obvious at the outset how significant a given risk may turn out to be. In risk identification, the best choice is to err on the side of inclusion, not exclusion. The tools of risk analysis will help us winnow out the risks that justify response, but that’s in subsequent steps. For now, the best strategy is to go for quantity over quality.

While the process of risk identification is normally described as something that takes place at the beginning of the project, that’s not enough. Risks change as the project moves forward. Some risks drop off the radar while other grow in intensity. Risk identification, therefore, must be a continual activity, not merely a one-time action.

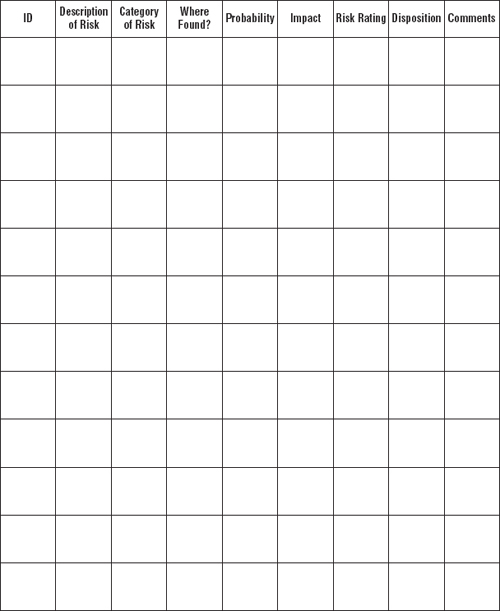

RISK REGISTER

The number of risks on a project can grow quite large, and managing your risk information can pose challenges. Start by creating a risk register, a centralized place where you write down the risks you collect. This can be as simple as a spreadsheet, or in some cases, even as low-tech as a legal pad. At the high end, advanced risk management and monitoring systems can take many millions of dollars to develop and implement. If you’re in the kind of business that warrants such an approach, you probably already have something in place, even if there’s room for improvement.

The basic information you need to gather about a given risk is pretty much the same, however, whether you’re dealing with one risk or thousands, or with one dollar or millions. Exhibit 2-1 illustrates a basic risk register format and identifies the fundamental information you need to gather about any given risk.

Risk ID

The risk identification number labels the risk. If you decide to number risks, make sure the number cannot be confused easily with other numbering systems at work on your project.

Description of Risk

A description of risk is often written as an “if–then” statement, containing the condition (the circumstances that would make the risk event occur) and the consequence (the description of the outcome should it occur).

• “If our competition releases its new product before ours is ready, the chance our product will dominate its market is reduced.”

• “If we do not complete the documentation by January 21, we will have to pay a contract penalty of $37,000.”

Category of Risk

Grouping risks together by common factors helps you manage them more easily. If there are numerous safety risks involved with the construction portion, safety would be a useful risk category. If there are risks involving interest rates and the stock market, financial risks would make another good category.

Some organizations establish standard risk categories; if your organization has such categories, you should use them. If all the projects in your functional area are close enough in subject matter and circumstances, you may wish to establish standard risk categories for those projects, even if your organization doesn’t require it.

Where Found?

The systematic search for risk includes a list of places where risks might be found. For example, if there is a list of requirements, you would normally inspect the requirements for risks associated with them. Under “Where Found?” you would list “Requirements.” If the plan contains a Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) listing all the tasks, you would normally look at the individual tasks for associated risks. Under “Where Found?” you would list “WBS.”

Probability of Occurrence

Occasionally, you may have a specific number for this space based on a long history of actual data: “There is a 20% chance of component failure.” More often, you can only provide a general indication—or your best guess. You might rate probability as “Low,” “Medium,” or “High,” or on a 1-5 scale. This estimate is subject to revision as you look more closely at a given risk.

Nature and Degree of Impact

Here too, you may have a specific number (“This would cost us $15,000”), or you may only be able to provide a general description of the impact. (“It would embarrass us in the eyes of the customer and jeopardize repeat business”). Sometimes, you can only say “Low,” “Medium,” or “High.” This information also tends to evolve as you look deeper.

For business risk, you must list both upside and downside values. “If the information from the preliminary engineering study is confirmed by these tests, per-unit manufacturing costs should drop by 40%. If the results are negative, per-unit manufacturing costs will remain at current levels.”

Risk Rating

This is the answer to the equation R = P × I. If you do not have numbers for probability and impact, the risk rating will also be imprecise: low, medium, or high. That’s usually enough to get started.

Disposition

What do you do with the risk after you have analyzed it? Does it go on a “parking lot” with other minor risks that won’t receive much attention? is it a major priority requiring significant effort and resources? Should you handle the risk yourself, or should another department or group (or the customer, for that matter) be the proper owner and manager of the risk? your choice of action goes here: the disposition of the risk.

Comments

If there is additional information necessary to the understanding of this risk, it goes here.

HOW TO IDENTIFY RISKS

A potential risk exists in every declarative statement about your project. “The deadline is February 15” contains the potential risk that you won’t be done by February 15. Perhaps February 15 gives you plenty of time and the risk is quite low; perhaps February 15 gives you a wholly inadequate amount of time to get the work done and the risk of failure is high.

Then there’s the cost of failure. Perhaps there’s a $1,000,000 contract penalty if you’re late; perhaps no one really cares as long as they get it by the end of the month. The risk is the likelihood you’ll be late times the cost if you are. Inadequate time and big penalty = serious risk. Plenty of time and no penalty for missing the deadline = trivial risk.

Risks can be about deadlines, budgets, or performance goals: the risk of not being done on February 15; the risk of spending more than the budgetary estimate of $125,000; the risk that the product won’t pass acceptance testing.

Risks can be about outside factors: the risk that customer requirements will change; the risk that interest rates will rise or fall; the risk that your competitors will beat you to market or vice versa.

Risks can be about the potential outcome of events: the risk that your prototype will fail its initial test; the risk that your proposed solution won’t work as well as you hope; the risk that good safety practices can’t prevent every conceivable accident.

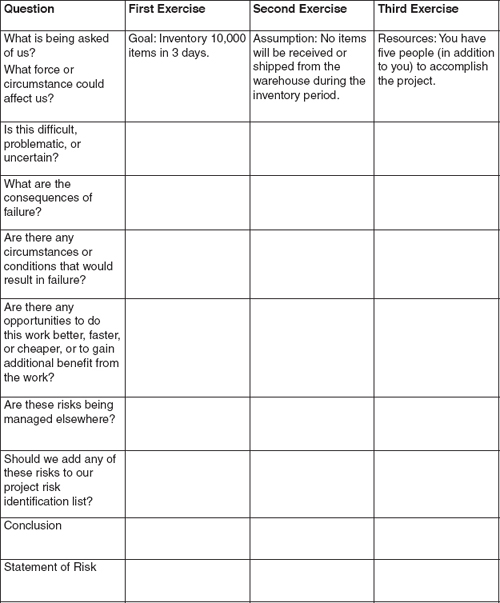

The process of risk identification involves looking for the risk events and situations of potential concern. Exhibit 2-2 lists questions to ask as you look at the details of your project environment.

You don’t have to write down everything in this level of detail. We are doing so here so that the thought process is made explicit. The only things you need to write down are the risks that you decide are serious enough to warrant further study—and the place to write those risks is on the risk register.

Exhibits 2-3, 2-4, and 2-5 provide examples of the risk identification process. Following those three exhibits, Exercise 2-1 provides you with a practice opportunity to do it yourself.

Questioning Risks

Sample Risk from a Requirements Document

| Question | Answer |

What is being asked of us? What force or circumstance could affect us? |

Requirement: Parts must be machined to a tolerance of ±1/32". |

Is this difficult, problematic, or uncertain? |

No. The machinery we use is capable of machining to much smaller tolerances, as low as ±1/128". We have trained operators who have done this hundreds of times. The schedule provides sufficient time for the job. |

What are the consequences of failure? |

Parts outside tolerance may result in more mechanical failures in use. The consequence to the customer of failure is loss of capacity, which can be measured in money. Safety risk (harm to people) as a result of a mechanical failure is not an issue in this case. |

Are there any circumstances or conditions that would result in failure? |

Yes. If the schedule is too aggressive, the rate of error tends to increase. Here, the schedule does not appear to be aggressive. Failure to maintain and properly operate the machinery would also result in problems. However, we do have a maintenance program. Even trained operators with good equipment can make mistakes. That’s why we have a quality control procedure to verify that parts are within tolerance before they get assembled into the final product. |

Are there any opportunities to do this work better, faster, or cheaper, or to gain additional benefit from the work? |

Doing quality work on time and budget is one of the competitive strengths of this company; we should be able to reinforce and add to that reputation. There is new machinery available that could potentially improve what we do, but it’s not cost-effective to buy it for this project alone. Management is currently reviewing whether it makes sense for the company as a whole. |

Are these risks being managed elsewhere? |

Yes. Plant maintenance and quality control processes already exist and appear sufficient to the potential risk. |

Should we add any of these risks to our project risk identification list? |

No. They are being managed elsewhere. |

Conclusion |

No project level risks. |

Statement of Risk |

N/A |

Sample Risk from a Project Charter or Statement of Work

| Question | Answer |

What is being asked of us? What force or circumstance could affect us? |

Goal: Produce 25,000 widgets and ship them to the customer no later than the end of next month. |

Is this difficult, problematic, or uncertain? |

There is some potential uncertainty. The 25,000 number itself is not too much for the capacity of the plant. We do, however, experience occasional overload with multiple jobs that can severely disrupt delivery dates. |

What are the consequences of failure? |

Damage to reputation; effect on future business from this customer, in rare cases, claims for damages. |

Are there any circumstances or conditions that would result in failure? |

Uncertainty in scheduling sometimes means capacity is strained more than usual. The priority of other work may be higher than the priority of our own. Equipment breakdowns sometimes happen even with excellent maintenance. |

Are there any opportunities to do this work better, faster, or cheaper, or to gain additional benefit from the work? |

Our existing initiative to improve shop floor scheduling has the potential to improve performance in time and cost. By supporting it, we make all the projects a little better. |

Are these risks being managed elsewhere? |

Partially. There is a plant scheduling function that has primary jurisdiction over this part of our project. However, we are still responsible for getting the product to the customer on time, and plant scheduling problems won’t excuse our failure to do so. |

Should we add any of these risks to our project risk identification list? |

Yes. While scheduling problems don’t occur often, they can result in serious problems when they do. It’s our responsibility to make sure we get things done. |

Conclusion |

Low Probability/High Impact Risk |

Statement of Risk |

If too many other projects schedule manufacturing time to coincide with ours, the plant production schedule may not be able to support our deadline. |

Sample Risk from a Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) Work Package

Exercise 2-1

Exercise 2-1

Risk Identification Practice

For this exercise, your project is to conduct an end-of-year inventory in a large warehouse. The warehouse will be closed for shipping for a three-day period, and must be able to resume operations on the fourth day. Your project team consists of three warehouse workers and two people from the supply department. There are approximately 10,000 items in the inventory.

SYSTEMATIC RISK IDENTIFICATION

There are many tools to help you root out risk wherever it may be hiding. Approach risk identification in a systematic manner. Make a list of the places you will look and the tools you will use to ensure you’ve done a comprehensive job.

Find risks by examining project documentation; brainstorming, analyzing and deconstructing project elements; and using formal risk management tools.

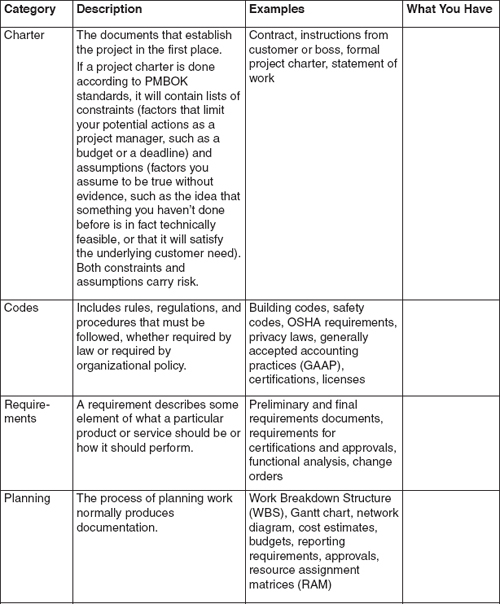

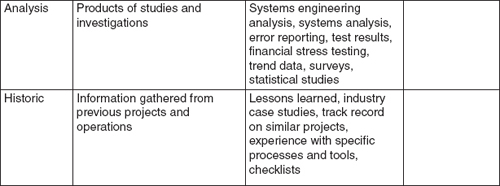

Documentation

A project or operation tends to produce a lot of paper (or its electronic equivalent). There are contracts, instructions, requirements, project charters, plans, standards, policies, and much more. Many items in all this documentation involve risk, so the first place to start in identifying the risks in your environment is with a thorough and systematic document review. Start by identifying and collecting the documentation available.

Exhibit 2-6 lists common types of project documentation. There’s some extra space provided so you can write down which of these sources apply to your situation. The amount of information and documentation tends to increase over time, so this step needs to continue as you move through the project life cycle.

Brainstorming

Both structured and unstructured brainstorming sessions uncover project risks. A simple unstructured brainstorming session is as simple as gathering parties together and saying “Let’s brainstorm the risks.” The purpose of risk identification—looking at all risks—matches well with the fundamental brainstorming rule of welcoming all ideas and withholding criticism.

Standard Brainstorming Techniques

Aside from the subject matter, there’s nothing particularly different about brainstorming risks as opposed to brainstorming anything else. Exhibit 2-7 lists standard rules common to all brainstorming sessions.

After a brainstorming session, there’s usually a process to winnow out the valuable ideas. The output—couched as statements of risk—is added to the risk register.

Negative Brainstorming

There are many different ways to brainstorm, and we’ve had good results with multiple techniques. One specific brainstorming technique has particular value when the topic is risk: negative brainstorming (Dobson and leemann, 111)—the focus on why things won’t work or will go wrong. Exhibit 2-8 describes the process.

As with all brainstorming, welcome all ideas and withhold criticism until the session is over. The purpose of risk identification is to make sure all potential risks are considered, so err on the side of inclusion.

xhibit 2-7

xhibit 2-7

Brainstorming Rules

1. Define the problem.

2. Select participants.

3. Set ground rules.

4. Define the brainstorming question or goal.

5. Welcome all ideas.

6. Focus on quantity, not quality.

7. Withhold criticism.

Diagramming Techniques

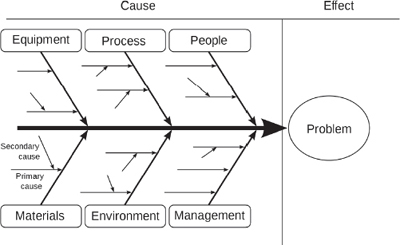

Risk identification borrows tools from other management disciplines as well. Two often-used tools are the cause-and-effect diagram and SWOT analysis.

Exhibit 2-9 shows a cause-and-effect diagram, also known as an Ishikawa diagram or fishbone diagram. The cause-and-effect diagram is a structured way to brainstorm root causes of risk by focusing on all the areas where the risk might live. To use this diagram the brainstorm team should address a potential problem area, then look for the ways each of the categories might contribute to the problem.

Negative Brainstorming

The goal of negative brainstorming is to identify areas of downside risk and vulnerability in your project environment so that you can decide how to address these areas. (Regular brainstorming does a fine job on upside risk and opportunity.)

1. Follow the normal brainstorming process from Exhibit 2-7 except as noted.

2. For the brainstorming question, select a negative question, one that focuses on failure and bad luck.

• Why is this project impossible?

• What can’t we do?

• How will other people and circumstances keep us from succeeding?

• What ideas are absolutely not worth trying?

• What’s the worst possible decision or action we could take right now?

• What could turn this into a complete catastrophe?

• Why are we already doomed to fail?

3. Strive for a maximum number of answers. Do not provide happy thoughts, corrective actions, or solutions.

4. When the negative brainstorming session is over, discuss which risks need to be added to the risk register, which risks are unimportant, and which risks are easily solved or dealt with by existing systems.

xhibit 2-9

xhibit 2-9

Cause and Effect Diagram

Credit: Fabian Lange

A format for a SWOT analysis is shown in Exercise 2-2. In a SWOT analysis, the group brainstorms a particular area of the project, looking at four different characteristics: strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. Strengths and opportunities are beneficial to the project; they help achieve the objective or make it better. Weaknesses and threats are harmful to the objective; they make it less likely that you will achieve it or that you will achieve less.

Strengths and weaknesses are internal to the project; that is, they are characteristics of the organization and the people in it. Opportunities and threats are external to the project; that is, they are part of the environment.

Exercise 2-2

Exercise 2-2

SWOT Analysis

Continuing with the inventory project from Exercise 2-1, prepare a SWOT analysis for the project.

Checklists

Before an airplane takes off, the pilot typically uses a checklist to make sure nothing has been overlooked. A checklist isn’t ever exhaustive, of course, but it guards against common errors and provides early warning of certain risks. If you do the same kind of project over and over again, checklists are useful tools for risk management. A good checklist not only identifies risk but also reduces it at the same time. “Landing gear handle down” addresses the risk that the landing gear handle might be in the wrong position for takeoff.

While checklists don’t substitute for comprehensive risk management, they are a significant aid to compensating for inattention or memory lapses—something almost all of us have been guilty of at one time or another.

Expert Judgment

If you and the project team have little experience in a particular risk area, it’s a very good idea to experts who can advise you about risks and responses. The two concerns, of course, are whether the person being consulted is in fact an expert, and whether the expert has a bias you need to take into account.

OUTPUT FROM RISK IDENTIFICATION PROCESS

The output of risk identification is simply the risk register—a list of the risks you’ve identified. Of course, you’re not nearly done. Risk identification is only the first step in a good risk management process. Many of the risks you identify need further analysis to determine how serious they are. Some risks you’ll end up choosing to accept, and others will need a comprehensive response. In between identifying the risks and deciding what (if anything) to do about them comes the stage known as risk analysis, the subject of the next several chapters.

Remember that risk management continues throughout the life of the project. No matter how well your initial risk identification process goes, the nature of the project always evolves over time. Continue to add items to the risk register as you discover them, and follow through the rest of the process steps with these new risks as well.

Risk identification, as the name suggests, is the process of identifying potential risks that may require some action on our part. Risk identification includes both business risks and pure risks. Because it’s not always obvious from the outset how serious a potential risk is, risk identification tries to err on the side of inclusion. If you’re not sure whether it’s a risk, write it down.

Start by creating a risk register, a centralized place where you write down the risks you collect. A risk register contains a description of the risk, the category in which it belongs, where you located it, your initial estimate of its probability and impact, an overall initial risk rating (low, medium, or high), and any comments or background needed to understand the context of the risk.

A potential risk exists in every declarative statement about your project. If it’s less than certain you’ll achieve the stated goal, then there is a risk. Risks, of course, vary in seriousness, and some risks are so improbable or have such a minor effect that there is no value in addressing them. Some risks involve circumstances of the project or the consequences of your own actions; other risks are part of the environment and you may have little control over whether they occur.

To make an initial assessment of a risk, consider the following questions:

• What is being asked of us, or what force or circumstance could affect us?

• is this difficult, problematic, or uncertain?

• What are the consequences of failure?

• Are there any circumstances or conditions that would result in failure?

• Are there any opportunities to do this work better, faster, or cheaper, or to gain additional benefit from the work?

• Are these risks being managed elsewhere?

• Should we add any of these risks to our project risk identification list?

If the answer is yes, add them to the risk register. Please note that for the most part you can ask these questions without writing everything down; only write down what you discover that is of significance. If there’s doubt, of course, err on the side of inclusion.

A systematic process of risk identification normally starts with a comprehensive document review, and may also including techniques of brainstorming, various diagramming tools (such as cause-and-effect diagrams and SWOT analysis), and checklists. It’s also a good idea to identify experts to advise you in risk areas with which you and your team are not familiar.

The output from the risk identification process is a completed risk register. No matter how well your initial risk identification process goes, the nature of the project always evolves over time. Continue to add items to the risk register as you discover them.

The next step in the risk management process is risk analysis.

1. Two factors in assessing the seriousness of a given risk are:

(a) contract penalties and customer satisfaction.

(b) risk rating and risk register position.

(c) the likelihood of the risk occurring and the consequences if it should occur.

(d) the cost of responding to the risk compared to the total budget of the project.

1. (c)

2. A systematic risk identification process needs to be performed:

(a) only at the outset of the project as part of the risk plan.

(b) every six weeks.

(c) by professional risk managers.

(d) throughout the project life cycle because of changes in circumstances and information.

2. (d)

3. in describing a risk formally, the statement of risk should always include:

(a) the probability and impact estimate for the identified risk.

(b) any proposed solutions or responses to the risk.

(c) the condition that provides concern and the consequence that would result.

(d) the category in which the risk falls.

3. (c)

4. Risk identification is concerned primarily with:

(a) listing risks that give us potential concern.

(b) identifying pure risks on projects.

(c) identifying business risks on projects.

(d) analyzing risks for probability and impact.

4. (a)

5. in the negative brainstorming technique, risk managers should:

(a) select a negative question to focus brainstorming efforts.

(b) ensure that the group develops corrective actions for the risks it identifies before moving on.

(c) focus on costs associated with risks.

(d) keep the brainstorming group small.

5. (a)

Review Questions

Review Questions