Risk Monitoring and Control

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

• Define key elements in a risk management plan and a risk management policy.

• Implement a variety of project risk monitoring and control tools, including monitoring and control metrics; early warning indicators; common concepts of Earned Value Project Management (EV or EVM) including planned value, earned value, and actual cost; and schedule and cost performance indices based on earned value metrics.

• Identify the elements in a change management system.

• Explain why risk identification and risk analysis must continue throughout the project life cycle.

• Assess risk management effectiveness during project “lessons learned.”

Estimated timing for this chapter:

| Reading | 50 minutes |

| Exercises | 50 minutes |

| Review Questions | 10 minutes |

| Total Time | 1 hour 50 minutes |

RISK MANAGEMENT PROCESSES IN PROJECT EXECUTION, MONITORING AND CONTROL, AND CLOSEOUT

We’ve now analyzed a single risk, but projects rarely have just one risk. Projects have a portfolio of risk, usually including both upside and downside risks. Some of the risks are known (or at least knowable); some of the risks are at least initially unknown.

While the topic of this course is project risk and cost analysis, the job isn’t complete until the risk response plan is in place and the risks are managed properly. In this chapter, we’ll provide an overview of the aftermath of the risk analysis process.

RISK MANAGEMENT PLANS AND POLICIES

A risk management plan is part of any well-prepared project management plan. It identifies and describes the risks, rates their relative seriousness by considering their probability and impact, lists any planned responses or actions intended to reduce downside risks or improve upside risks, and explains how the project team will monitor risks and responses for effectiveness.

A risk management policy is a document that applies to an entire organization or category of projects. It describes how the organization wants risk management to be performed, which projects and activities are covered by the policy, the definitions and steps involved in the process, the types of reports and documents that need to be prepared and disseminated, who must be consulted or who must approve risk responses, and similar matters.

Your organization either has or doesn’t have a formal risk management policy in place. If it does, then your risk management planning activities must conform to it. If it doesn’t, you may want to prepare one for your own projects simply to avoid the need to start from scratch each time.

Risk Management Policy Development

A formal risk management policy can be a valuable asset when projects and operations carry with them the possibility of serious organizational consequences. In our judgment, a risk management policy should be considered an organizational best practice when it comes to risk management.

There is little advantage in creating a risk management policy from scratch, because there are numerous templates and guidelines available to help you. Many of them are specific to certain industries or occupation, but by and large they follow the same format. You will find links to a sampling of risk management templates in the Additional Resources section of this book, and more are being added all the time.

Regardless of the organization or category of risk, all risk management policies must address certain questions and issues. The following guidelines are designed to help your organization in preparing a risk management policy.

Philosophy, Approach, Scope

The more explicit and clear the organization’s attitude toward risk, the easier it will be for individual projects and operations to behave in accordance with it. A statement of purpose, scope, and commitment helps readers make sense of and apply what is to follow. Consider the following questions:

What kinds of risks are most important?

If you manage a white-water rafting business, for example, there’s an inherent level of physical danger to participants. A risk management policy might emphasize the importance of safety precautions, safety training, and emergency medicine. If your business manages investment portfolios for customers, the danger is to financial wealth rather than physical health, and the risk management policy adjusts accordingly.

Defining the areas of greatest concern helps focus attention where you most need it. This doesn’t mean you won’t address risks outside the areas of primary concern, of course, but they normally have to rise to a higher level for you to take them as seriously.

Think About It …

Think About It …

What kinds, categories, or areas of risk are most important to your organization, group, or type of project?

What kinds of risks do you want people to take?

Business risk, as we’ve discussed, combines upside risk and downside risk in the same decision. Avoiding pure risk (at the right price) is clearly prudent, but avoiding business risk eliminates the chance of gain along with the chance of loss.

To avoid any possibility of an accident in white-water rafting, the obvious solution is to avoid white-water rafting, but you also avoid the exhilaration and fun from the activity. To avoid any chance of financial loss, you can keep your money in the safest possible investments, but in doing so you may miss out on valuable returns.

What kinds, categories, or areas of risks should be encouraged? What kinds of risks are potentially beneficial to the project, the organization, or the customers?

What kinds of risks do you want people to avoid?

Some risks are unacceptable as a matter of policy, and those need to be spelled out. For example, a company might express a strong unwillingness to accept risks in ethical matters, risks involving the potential for injury, or other categories.

Notice that being unwilling to accept risk in a particular area may simply shift the impact of the risk to another area. If you’re unwilling to accept the possibility of physical injury from your products, you’ll usually end up paying for additional safety measures. The risk switches from physical harm to financial impact.

Think About It …

Think About It …

What kinds of risks should be avoided as a matter of policy? What is the threshold of acceptability on these risks?

What projects and risks are covered?

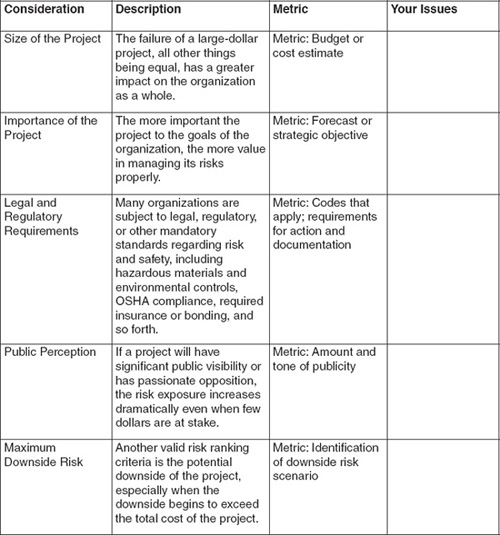

Failing to perform adequate risk management can be catastrophic. At the same time, risk management costs money and takes away resources that could be employed elsewhere. In order to strike a balance between the cost of risk management and its benefits a number of different questions should be considered, as outlined in Exhibit 10-1. We’ve provided space for your issues and considerations.

We do not recommend that projects below the threshold of formal risk management planning be exempt from risk management altogether, of course. However, the degree of rigor and detail appropriate for smaller projects may be far lower than is appropriate for larger or more inherently dangerous ones.

Risk Management Methodology and Process

While most risk management methodologies follow the same broad outline (initiation, analysis, response planning, action), the details of preferred tools, approaches, and steps vary greatly. Even for organizations that use an industry standard, such as the PMBOK®, as a template, there are still numerous details that must be customized for any organization, such as who must be consulted on given risks and how risk data will be integrated with other information. Consider the following:

Definitions. Common vocabulary matters a lot. If a risk is “unlikely,” does that mean a probability lower than 50% or lower than 25%? What constitutes a “significant” risk?

Reporting and Documentation. How will we keep track of risks? What information needs to be archived? Who should be informed of which risks? How will risk management be handled within other project management functions?

Approvals and Authority. Who is responsible for identifying risks and preparing the risk management plan? Who must approve risks in particular categories? Who decides whether the total risk level of a project is acceptable or unacceptable?

PROJECT RISK MONITORING AND CONTROL SYSTEMS

In project risk analysis and project risk response planning, we identified the risks that required responses, made sure we understood those risks as thoroughly as possible, and developed responses and action steps to implement those responses. Along with our risk responses, we developed metrics: indicators that help us understand what’s going on with a particular risk.

How will we make sure these plans and strategies are implemented, and that the things we said we were going to do actually get done? The process of doing this is known as project monitoring and control, the final part of our phased approach to risk management planning.

Managing the Project Risk Environment

Our individual risk response plans form the basis of one aspect of project monitoring and control. In addition, risks are often managed collectively and by category, as in the case of a shop safety program. The safety program doesn’t specifically care about the consequence to your project, but works to prevent accidents across the board. Project risk monitoring and control has a collective side as well. In addition to managing specific risks, you need to monitor and control the general project environment as part of an effective risk response.

Many of the tools you use to manage the project offer information and insight into the risk environment as well. A weekly report provides status information to check against the plan. If there are discrepancies in, say, the schedule, you’ve just found evidence of a time risk to the project. If the cost of raw widget stock is higher than the planned number, you know there’s a cost issue. If the test report says that the new widget design didn’t pass the pressure test, you’ve uncovered a performance issue.

There are four areas of fundamental concern in your project risk environment:

1. Information that suggests that specific risks have been triggered or that they are not going to occur.

2. Information that suggests that your planned risk responses are working or are not working as intended.

3. Information that suggests project and environmental conditions have changed or not changed from your expectations or history.

4. Information that suggests underlying or structural issues with your project or plan exist or don’t exist.

In everything you do to manage, monitor, and control the project for which you are responsible, you need to keep these concerns in mind. As we’ve pointed out elsewhere, the earlier you learn that you have a problem or an opportunity, the greater your ability to manage it to best effect.

Add a section on “Risks” to any status reporting form you use so that people write about what they see in the near future as well as about what has happened in the recent past. Use part of project staff meetings to discuss the upcoming uncertainties as well as the status of current work.

Establishing Risk Metrics and Early Warning Indicators

In addition to metrics, triggers, and early warning indicators for specific planned risks, you also need to establish general metrics that reveal unusual trends early, and that distinguish between ordinary variation and significant divergence from the expected norm. We are looking for significant variance from the plan, in areas of cost, time, and performance.

Often, a project that’s within ±5-10% of budget estimates is considered on-budget, especially when we’re dealing with large round numbers and uncertainty. If, on the other hand, the variance started out at 1% and it’s gone to 8%, it might be sensible to look for any potential underlying problem well before costs get out of hand.

If you work on a large project or in an organization that uses performance measuring software systems, you may have a great deal of specific information available that you can use to monitor and control your risks. Financial data, market performance, test results, and productivity metrics can be of help.

If your project management environment contains a project management office (PMO), uses enterprise grade software for project management, or has implemented Earned Value Project Management (EV or EVM), you have even more tools at your disposal to monitor and control risks on your project. A PMO often keeps performance data on other projects that you can use to baseline your own effectiveness. Enterprise-grade project management software, capable of handling tens of thousands of activities in tight relationships, provides extensive tools for analyzing and tracing chains of events.

Earned Value Method (EVM) Performance Index Ratios

Example: Today, the schedule says you should have finished Task A, which was budgeted at $1,000, and half of Task B, which has a total planned cost of $1,000 as well (total of $1,500). You’ve spent $1,750, but you’ve accomplished all of Task A and all of Task B as well. How are you doing?

PV = $1,500 AC = $1,750 EV = $2,000

SPI = $2,000 / $1,500 = 1.33 (133%) CPI = $2,000 / $1,750 = 1.14 (114%)

Example: Today, the schedule says you should have finished Task D ($5,000), Task E ($2,500), and half of Task F (50% of $7,500). You’ve only finished Tasks D and E, and you’ve spent $8,250 so far. How are you doing?

PV = $11,250 AC = $8,250 EV = $7,500

SPI = $7,500 / $11,250 = 0.67 (67%) CPI = $7,500 / $8,250 = 0.91 (91%)

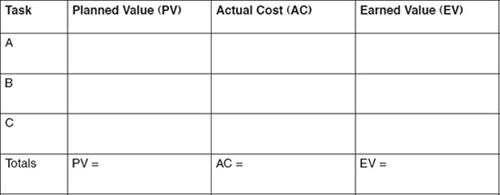

Earned Value Project Management

Earned Value Project Management requires a self-study course in itself, and a full discussion is well outside the scope of this book. If EVM is required for your projects or by your customers, then you will need to become familiar with it if you are not already.

The EV method starts with three numbers: The planned value (PV) measures how much work we should have accomplished by a given date and how much we should have spent to accomplish it. To that, we add the actual cost (AC), what we actually spent for what we actually did. Finally, we add the earned value (EV), which measures what we should have spent for what we actually did.

Earned value allows you to determine the amount of cost or schedule variance, but from a risk point of view, it’s valuable to pay particular attention to two ratios that measure performance. The cost performance index (CPI) is the ratio of the earned value to the actual cost (CPI = EV / AC), and the schedule performance index (SPI) is the ratio of the earned value to the planned value (SPI = EV / PV). Exercise 10-1 shows you how to do it.

Exercise 10-1

Exercise 10-1

Earned Value Method (EVM) Performance Index Ratios

Today, the schedule says you should be completely done with Task A ($7,500) and Task B ($5,000), and half done with Task C (total cost of $10,000). You have completed 75% of Task A, spending $6,000 to date; all of Task B at a cost of $6,000; and you are completely done Task C, having spent $12,000. How are you doing?

SPI =_______________

CPI =_______________

What conclusions can you draw about this project?

An SPI or CPI of 1.00 (100%) means you’re exactly on track. Small variances (less than 5% or 10% on either side, depending on the type of project and organization) are not usually significant; anything above 10% either way demands investigation.

Implementing and Monitoring Risk Responses

Even if you develop great risk responses, they don’t do very much unless they’re implemented. We have suggested the best place for many risk responses is in the project plan, and indeed there are always tasks in any project plan that exist solely to address risk. If there were no chance of a failure, there would be no need for inspection or testing. If the design were certain to work, it would not need to be reviewed. Testing, reviews, and many other activities are best treated the same way as any other work package.

A risk response plan can consist of many sorts of actions, as shown in Exhibit 10-3.

Sample Risk Response Action Plans

Risk: Customer orders may need to be filled during inventory.

Response: Be prepared to work overtime to meet both the needs of the customer and the need for the inventory.

Action Steps:

1. Check with Sales Manager the week before the inventory to see if customer emergencies are expected.

2. Advise team members of the potential for last-minute overtime so they can adjust personal plans as necessary.

3. Recruit two backup team members who will be available to work if needed; include them in training session.

4. If it turns out that overtime or extra staff are needed, prepare authorization requests and timesheets to submit to payroll.

Corrective Actions and Unplanned Responses

Most risk responses are implemented whether or not the risk occurs. If you buy insurance, you may or may not end up having a claim. If you conduct testing, you may or may not find anything wrong. While the risk condition itself may be uncertain, the response is not.

Implementing a contingent response is known as corrective action. Responding to an unplanned risk is known as a workaround. The difference, of course, is that you have at least a general course of action in mind in the first case, and may be scrambling to find an acceptable solution in the second case.

To make a contingent response effective, you need to establish a risk trigger, a set of conditions or circumstances that activate the response. This is particularly important when your risk response requires a head start on the risk event itself.

Watching “Watch and Wait” Risks

We have identified “watch and wait” risks, characterized as having (1) low probability, (2) potentially catastrophic impact, and (3) expensive mitigation. Because of the cost of response, you prefer not to spend the resources unless you have reason to believe the risk event is actually going to occur, or is looking tremendously more likely.

What kind of metrics will you use to observe the risks? Are there leading indicators of potentially adverse trends? Are there particular circumstances that alter the probability or impact of the risk?

CHANGE MANAGEMENT AND RISK

It’s far from unusual to make changes to the project scope and objectives during the project life cycle. Sometimes new information is received; sometimes circumstances or needs change; and sometimes people simply change their minds. The result is a change order, whether formal or informal. They are part of life for any project manager.

Changes, of course, frequently contain risks—and in the context of our project, they are new risks, not yet included in our risk evaluation and response process. While it’s not always possible to perform a full risk analysis before deciding what to do about a given change (sometimes the change is a fact whether you like it or not), it’s important to perform a risk evaluation as early as practical so that you can respond or adjust as needed.

Planning for Changes

Virtually every authority in project management recommends a formal change management system, and it’s fairly obvious why this is a good idea. Changes cost money and time, they may affect other parts of the project, and they aren’t always communicated effectively. Failing to review and document changes effectively opens your project to huge and unnecessary risk.

There are many right ways to put together a change management system, and they vary by organization and environment. At a minimum, they usually include the following:

• A way to document the change

• A way to allocate any associated costs for the change

• Someone who can approve or reject the change

Risk analysis and risk response planning are necessarily part of all three steps, whether they are done formally or informally. Because changes are a particularly rich source of project risk, we recommend a formal approach in almost all cases. If a change is to be made to an in-progress project, someone (either the project manager, or if the risk is specialized, the particular risk owner) needs to perform a risk analysis and identify issues of potential concern.

Avoid becoming the “boy who cried wolf.” Your role is to figure out how to make the change work, rather than to show why it cannot. In some cases, an honest evaluation will reveal risks so serious that they require a reassessment of whether the proposed change is appropriate, but that decision normally belongs to customers or managers at a higher level. Your role is to provide objective data, and when possible to offer solutions or useful alternatives.

Do you have a formal change management plan? Does it do a satisfactory job of evaluating new risks associated with changes? How would you improve it?

Managing Unplanned Change

Problem solving and crisis management are all too frequently a fact of organizational and project life. The goal of risk management is to reduce the number and scope of problems and crises, but it’s unrealistic to expect that even the finest risk management will make everything go away.

By their very nature, problems tend to be specific, unexpected, and unique. Risk management can’t provide individual answers in advance. We do get advantages from risk management even for the most unplanned and unexpected events, however. By establishing our monitoring system, we’re more likely to get an early warning. If we have resources available to address planned risks, they can be repurposed to manage unplanned ones as well.

REVISITING RISK IDENTIFICATION AND RISK ANALYSIS

Time—and therefore risk—marches on. When we perform our initial risk identification during the early planning stages of the project, we see a great deal of uncertainty. As the project moves forward in time, however, the future slowly becomes the present, and then quickly turns into the past. Risks turn into problems, or they don’t happen at all.

The events on our project change the risk picture for the future. If we suddenly get a huge influx of customer orders in the weeks leading up to our inventory date, and more of them than usual are emergencies, the chance that our inventory will be interrupted by the need to ship goes up dramatically. Instead of waiting for the actual order to work overtime, maybe it makes more sense to put the extra manpower on the job from the beginning to get it done as quickly as possible.

New risks appear with little or no warning. Two of the employees we planned to use on the inventory project have just quit, and they were the only two who had experience doing our inventory in previous years. To address the new set of risks, consider doing two things:

1. Add an item to your regular status meeting agenda to talk about new risks that should be added to the risk management plan. Assess those risks using qualitative risk analysis filtering, and conduct risk analysis and response planning for those you consider serious.

2. If the project will take months to complete, conduct a monthly risk review. Take the plan, existing risks, new risks, and performance data, and update the overall risk management plan.

Update the risk register and risk information sheets for new risks and for existing risks that have changed in nature, probability, or impact.

Closing Risks

At some point in the project, every risk reaches its expiration date—a point after which if the risk has not occurred, it can no longer occur. Before the test is run, the widget has a risk of failing the test. After the test has been run, the widget either passed or failed. Either way, there’s no longer a risk, but rather a non-event (it passed) or a problem (it failed).

When you decide that a risk needs to be monitored, managed, controlled, or watched, you should close the risk. Close a risk under the following circumstances:

1. The risk did not happen and it is no longer possible for it to happen.

2. The risk happened, and all of its consequences have played out, for better or worse.

3. The residual level of the risk is no longer worth the time and expense to monitor it.

When the project is complete, all the risks associated with the project are also closed. (Risks in the product, which you deliver to the customer or user, still remain, of course.)

Document when a risk is closed, either on the risk register or the risk information sheet, and list briefly why it has been closed. Keep information related to all risks, including closed ones, for two reasons. First, you need to review those risks and responses as part of “lessons learned,” and second, you may encounter similar risks on future projects and will be able to reuse risk analysis and response planning that you’ve already done.

RISK MANAGEMENT AND PROJECT “LESSONS LEARNED”

Every well-run project includes a post-mortem, or “lessons learned” exercise, and evaluating risk management and risk response is part of it. Consider the following questions:

• How did your estimates of probability and impact line up with reality?

• What risks occurred that you did not expect?

• What risks did you expect that did not occur?

• What assumptions about the project turned out be incorrect?

• What linkages or connections among the risks were not obvious?

• How well did your risk mitigation efforts and risk response plans operate?

• How effectively were you able to monitor conditions and get early warning of risk events?

• Were the risk management processes that you used cost-effective and appropriate for your project?

• What would you do differently next time?

• What did you learn on this project that will improve your ability to manage risks on future projects?

Keep risk response plans, risk analysis data, and actual project results to use as raw material for managing risks on future projects.

Risk management requires an overall process for implementation during the phases of project execution, monitoring, and control. A risk management plan is for an individual project; a risk management policy covers an entire organization or at least a category of projects.

Risk management policy addresses numerous questions:

• What kinds of risks are most important?

• What kinds of risks do you want people to take?

• What kinds of risks do you want people to avoid?

• What projects and risks are covered?

In addition to implementing specific risk responses, risks are also managed collectively and by category. Project monitoring and control activities, such as status reports or other data, provide raw information about risks, helping you to discover whether particular risks are being triggered, whether planned risk responses are working as intended, or whether environmental conditions have changed.

Project metrics take many forms. In the Earned Value Method (EVM), the planned value, actual cost, and earned value of a project allow you to measure schedule and cost performance on your project.

Risk response plans detailing action steps for a given risk are normally integrated into the overall project plan. In addition, you may need to implement corrective action (contingent responses) or workarounds (unplanned risks). Monitor “watch and wait risks” carefully.

Project changes create new risks and modify existing ones. A formal change management process has many virtues, including providing an opportunity for renewed risk management efforts. Risk identification and risk analysis need to be revisited as the project moves forward over time. Close risks when they can no longer happen, when all their consequences have played out, or when the residual risk is no longer cost-effective to monitor.

Finally, evaluate the effectiveness of risk management as part of lessons learned, and organize risk data on current projects so that it benefits future projects as well.

1. The schedule performance index (SPI) measures the ratio of the:

(a) earned value to the actual cost.

(b) actual cost to the planned value.

(c) planned value to the actual cost.

(d) earned value to the planned value.

1. (d)

2. A risk management policy includes which of the following elements?

(a) Risk identification and risk analysis information for the project

(b) How the organization wants risk management to be performed

(c) A list of planned risk responses and action steps

(d) Description of metrics and measurements to be used on the project

2. (b)

3. What is the effect of project change on project risk?

(a) Changes increase overall project risk.

(b) Changes only add to the list of risks.

(c) Changes create new risks and modify existing risks.

(d) Changes balance new risk with new opportunity.

3. (c)

4. What kinds of risks are most desirable? 4. (c)

(a) Pure risks

(b) Uncertain risks

(c) Business risks

(d) Nonfinancial risks

4. (c)

5. The cost performance index (CPI) measures the ratio of the:

(a) planned value to the actual cost.

(b) actual cost to the planned value.

(c) earned value to the actual cost.

(d) earned value to the planned value.

xhibit 10-1

xhibit 10-1

Review Questions

Review Questions