CHAPTER 5

Risk Identification and Hazard Assessment

IN ORDER TO EFFECTIVELY manage supply chain risk, you must first know what the risks are and fully understand their impact. A hazard assessment (or risk analysis or assessment) is conducted to identify the potential threats to the organization, quantify the impact of those risks on core business functions, document the threats, and then develop an approach for eliminating or decreasing the impact of the recognized threats. A hazard assessment and a business impact analysis are the two keystones of the business continuity planning lifecycle. (Business impact analysis is the subject of Chapter 6.)

A frequently cited quote from writer Frederick B. Wilcox reminds us that “You can’t steal second base and keep your foot on first,” and it is a generally accepted reality that risk is inherent in all aspects of business operations and that an acceptable level of risk is necessary for progress and achievement. The purpose of a hazard assessment and accompanying mitigation program is not to eliminate all hazards. A business certainly cannot function within the confines of a protective bubble, and even if it were possible to eliminate all current risks, new threats would continue to surface. The goal of business continuity is to identify all known threats, determine the organization’s acceptable level of risk or operational threshold of pain, and, based on that information, manage risks to a level that moves the organization closer to a goal of developing a capability to continue or quickly restore critical business functions when disasters occur.

There are three key ways in which the results of the hazard assessment are used:

1. To identify the vulnerabilities requiring the most immediate and extensive business continuity planning and act as guide for prioritizing the order in which risks are addressed

2. To provide a basis for developing a mitigation program to eliminate potential disasters as possible and lessen the impact of those that cannot be eliminated

3. To provide a foundation for the business continuity planning process

Once we have identified and quantified the threats that are most likely to occur and those that would create the greatest disruption to the company’s operations, it is then possible to determine how to most effectively manage them. Among the choices are absorbing the risk, transferring the risk, or reducing the impact of the risk through mitigation.

As the past does not necessarily predict the future and there is no way to see what the future has in store, conducting a hazard assessment does require some subjectivity and can never be totally accurate. Yet it goes far beyond the simple, reasonable assumption that your organization will experience a disaster at some point in the future. If implemented correctly, a hazard assessment provides invaluable planning guidance through a logical process of identifying, rationally evaluating, and addressing risks and their impacts, and it thereby avoids planning based on a lack of information, assumptions, or misinformation.

The Changing Face of Supply Chain Risks

Supply chains have never been so sophisticated or complex and, as a result, so vulnerable to risk. The lean production method introduced by production improvement expert and quality control pioneer W. Edwards Deming, as well as justin-time inventories, less vertical integration, dependence on single-source suppliers, and mounting reliance on cost-reducing suppliers often located in unstable areas of the globe, all contribute to a higher level of risk.

Many supply chain threats are not local to an organization. Globalization has led to lower production costs resulting from cheap labor and materials, along with added risks resulting from extended supply chains, decreased reliability, language barriers, suppliers’ further outsourcing the work, and transparency issues. Add to this mix terrorist threats, political unrest, shutdowns at shipping facilities, and economic instability. The end result is a recipe for potentially significant and long-term supply chain interruptions that have the potential to cascade across the organization and result in the loss of business and customers, severe long-term damage to reputation, and legal action.

Today, countless manufacturing companies actually produce very little. Rather, they purchase components and parts from multiple suppliers for assembly and distribution, creating a tremendous dependency on their supply networks. The ongoing push for a smaller physical footprint is often accomplished by streamlining the company’s facilities by removing operations and locations seen as being redundant, inefficient, or unnecessary. This results in having more eggs in fewer baskets.

The Effects of Natural Disasters

Of course, organizations whose operations are solely within national borders are also not immune to a changing disaster landscape. In the United States, for instance, the first decade of the millennium brought natural disasters that, while not necessarily unpredictable, were unprecedented in their magnitude and scope. While the Gulf States are all too familiar with hurricanes and flooding in the Midwest (particularly along the Mississippi) is a fact of life, two destructive events are examples of natural disasters that resulted in severe supply chain disruptions.

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina—one of the largest natural disasters in the history of the United States—destroyed key shipping and hauling infrastructure along the Gulf Coast from Florida to Texas. Rail and truck routes were closed, bridges were severely damaged or destroyed, and barge traffic was delayed. These transportation disruptions caused a frantic rush to recover and restore deliveries. Ports such as New Orleans, one of the world’s largest, were also impacted, leaving thousands of tons of goods and materials damaged or destroyed. This included forestry-related products, aluminum, natural rubber, and coffee.

The other destructive event was record severe flooding along the Mississippi in 2008, which destroyed rail bridges and washed out track, closed truck routes creating detours as long as 150 miles or more, and brought barge traffic to a near standstill. At one point, it was estimated that hundreds of railcars were backed up and as many as 100 barges were idled on a 300-mile stretch of the Mississippi. Some carriers placed embargos on deliveries. The immediate and ripple effects on companies along the Mississippi that are dependent on river traffic to move goods were enormous and included increased shipping costs as a result of the necessity to rely more on truck transit and less on intermodal delivery and in some cases varying lengths of closures of factories and other businesses.

Hazard Assessments and Understanding Threats from Disasters

A hazard assessment makes possible a more complete understanding of the threats that can impact the organization’s ability to function as intended and provides a framework within which to continue the planning process.

We know that “things” happen. In some cases, what makes an emergency a disaster is not knowing exactly what its severity or scope will be or when it will happen. In other cases, disasters not only are not on our radar screens; we could not even have imagined them in our worst nightmares. We must understand that in today’s uncertain times, there will always be new disasters we have not previously considered as the spectrum of threats to supply chain operations continues to change and expand, and both new risks that were previously not considered and long-known disasters create more damage and disruption than ever before. As a result, once the initial business continuity program is in place, it is important to regularly revisit the planning process to update the hazard assessment to reflect new threats and changes in the level of impact each threat will have on operations.

Identifying Supply Chain Risks

From a supply chain perspective, any event is a threat with the full potential to become a disaster if it results in a significant disruption of transportation, loss of inventory, the inability of suppliers to fulfill orders, the inability of the organization to fulfill orders, or the inability to communicate with customers, suppliers, transportation providers, or other stakeholders.

Internal and External Risks

In the past, it was a common practice for the hazard assessment process to focus almost exclusively on the most direct threats facing a company, such as a large and damaging fire in a building, a hurricane or earthquake, or a serious failure in the data center. But today, threats to the overall organization are also risks for the internal supply chain business units. Moreover, the supply chain has its own set of very inherent risks, many of which exist outside the organization. While some disasters may directly impact only the supply chain and may even be external to the organization, they must be fully considered for a hazard assessment to completely succeed in its purpose. The larger the enterprise, the greater the number of companies included in its supply chain and the greater the number of tiers all contributing to the number of potential risks. (The tiers include tier one suppliers that provide finished components, tier two suppliers that provide subcomponents or parts directly to tier one suppliers, tier three suppliers that provide raw materials to tier two suppliers, and so forth.) The more tiers, the greater the possibility that an event impacting a subsupplier may have a domino effect that accumulates into a major disruption for the customer company, or that a combination of small events may occur along the supply chain that culminate in a disaster before reaching the last link in the chain. Though indirect threats, such as the loss of a key supplier or a transportation interruption, can have an equal or more damaging impact on the continuity of the supply chain, these risks are often ignored or overlooked in the hazard assessment process.

Large-scale supply chain disruptions may be infrequent. Yet today, the risks increase, and the effects of a seeming minor disruption can be devastating. Risks lurk along the entire length and breadth of our often nontransparent supply chains. As a result of diverse sourcing locations for some companies, in particular those operating globally, shipping delays may be common, with causes as varied as natural disasters, political instability, labor union actions, exchange rate fluctuations, or capacity issues. Other threats include security issues in less stable countries, weather, shipping congestion, and equipment failures. Risk levels are increased when there is total reliance on a sole source provider or shipper.

Hazard Identification Process

The first step in the hazard assessment is to identify all risks, whether natural (such as hurricanes, earthquakes, and severe winter storms), technological (such as engineering failures, equipment failures, and power outages), or of human causes (such as arson, acts of terrorism, cyber attacks, and riots). None of us has perfect foresight, and while the past is not always the best way of knowing what will happen in the future, it can help us identify potential disasters. Companies in areas where there has been widespread flooding need to consider if future flooding may reach their location. The proximity to an earthquake fault line is a definite consideration. Organizations located in areas that have experienced wild land fires need to consider this hazard even though they may not have had facilities destroyed or damaged by past occurrences. All these and other hazards must be identified, both for internal operations and for outside entities upon which there is a dependency.

While hazards should be considered in a broad context, you should try to identify events that may actually occur. While anything is possible, the likelihood of a tsunami in Kansas does not merit consideration. If your organization has facilities in different geographic locations, a hazard assessment must be conducted to identify the varying hazards for each.

Do not overlook the obvious. I recall sitting in a conference with a client’s planning team at the beginning stage of conducting a hazard assessment. Everyone was contributing to the list of the company’s possible disasters. Throughout the process, I kept expecting someone to mention a threat that seemed evident to me as I heard the frequent and unmistakable sound of airplanes overhead. The business was located within the takeoff and landing patterns of three major metropolitan airports. Yet because the employees heard the noise of the planes on a daily basis, no one thought much about it, let alone considered the planes as a potential threat.

The same holds true for not-so-obvious nearby hazards. A gas refinery, a major highway or railway used to transport hazardous materials, or a business or government agency that may be the target for sabotage or terrorism can create a risk for your company simply due to proximity.

In short, all supply chain risks should be included in your assessment. For all entities in the chain—including suppliers, contractors, vendors, and transporters—be aware of their financial and stability issues and of the stability of your suppliers’ raw material supplies. The more critical the business partner, the greater the need to assess and manage the associated hazards.

Prodromes—events that might be indicators that warn that a disaster may occur either in the future or under slightly different circumstances—need to be identified as well. For example, let’s say shipments from a critical supplier whose deliveries have previously always been on time suddenly begin to be sporadically late. This happens more frequently, and the lag times become increasingly longer. These late deliveries are prodromes and might be early warning signs of a potential threat that needs to be managed before the situation becomes a disaster. All supplier-related risks should be identified and included in the hazard assessment.

It is also important to collect information from multiple sources. There are many different types of threats that must be considered, and no single source of information can include them all. Different sources identify different sets of risks to add to the assessment. Public safety officials and emergency agencies can provide valuable input and data, as can internal experts such as security, safety, facilities, and human resources.

After identifying all the possible threats to your business, consider how likely it is that the threat will occur. Finally, and perhaps most important, consider: Should this event occur, what will the impact likely be on your ability to continue your day-to-day business operations.

Conducting a hazard assessment requires making some assumptions, such as the likelihood that an identified threat will actually occur, and doing some forecasting. It is important to remember that even if your projections are off the mark by 10 or even as much as 20 percent, using reasonable assumptions is still preferable to not completing a hazard assessment and continuing the planning process in an information vacuum.

Mapping the Supply Chain

Successfully managing supply chain hazards requires a complete examination, analysis, and understanding of your full supply chain, both internal and external. It is critical to develop an in-depth understanding of the process flow of both goods and services. Take advantage of both your own experience and knowledge and that of other supply chain professionals in your company. An effective hazard assessment includes the insights of those who are involved in and have real-world knowledge of supply chain operations. This may be as simple as gathering all supply chain business unit managers together in a conference and together mapping the supply chain.

The Mapping Process

Developing a complete map likely requires several iterations. I suggest first creating the supply chain map on a white board to allow for additions, changes, and corrections. The representative from each business unit might use a different-colored marker to indicate his or her additions. This visual approach allows for some great what-if brainstorming while identifying all the organization’s supply chain hazards.

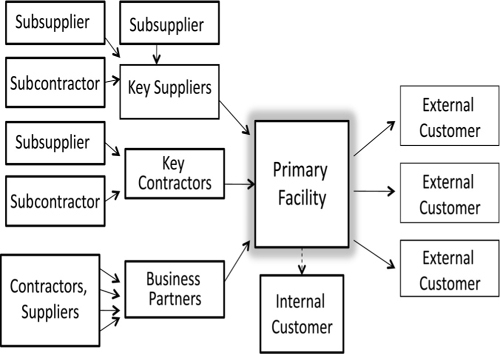

Begin your mapping activity with the basic supply chain links as shown in Figure 5-1. Starting with your organization’s facilities, add all upstream supply chain links such as tier one suppliers, contractors, and business partners, and their suppliers and contractors. Then add the downstream links such as distributors, wholesalers, retailers, and your customers. From there, create a map of the entire supply chain process and its logistics from end to end, internal and external, and all touch points upstream and downstream. Include suppliers, outsourcing, strategic partners, internal processes, shippers, customs brokers, and your customers. Once the basic mapping is complete, identify each strategic raw material and essential part or component at each upstream link of the chain. For each key supplier or contractor, list what it provides. Note if each is a sole source supplier and if not, what percentage of the overall amount required each provides. Also identify all tier two suppliers and contractors. For customers, identify what products or services you supply to each and what percentage of your overall annual sales that represents.

The supply chain map—a form of expanded flow chart— is a particularly helpful approach when a group of people are developing the hazard assessment. Each person can more quickly understand the visual representation and add his or her input. In larger, more complex organizations, this approach will likely uncover some misperceptions and gaps in understanding how each business unit fits in the bigger picture. This approach also makes it possible to more readily identify the interdependencies within the supply chain.

Once the supply chain has been mapped, identify all the things that can go wrong that will prevent delivering the company’s product or service within acceptable parameters. Two of the approaches for completing this task are the what-if and the checklist methods. Using the what-if approach, conduct a discussion or brainstorming session to identify what could go wrong at each juncture of the supply chain and what the consequences would be. The checklist approach involves working with a list of hazards and identifying those on the list that are threats to your supply chain This exercise will likely bring to mind other threats that are not on the list. A combination of the two may be even more effective. Use a list of known hazards as a starting point, and branch out from there to capture hazards that may be unique to your operations and location. (Appendix B contains a partial list of general hazards and a list of supply chain–specific risks to help you begin the hazard assessment process.)

Next, identify all potential disasters and unacceptable risks. This should include all potential bottlenecks, weak links, single points of failure, choke points, and roadblocks. Then, for each of the listed threats, answer three questions:

1. How likely is it that the threat will occur?

2. Has it happened in the past?

3. If it does occur, what will the impact be on our operations?

Once this process is complete, a computerized version of the detailed map can be created for all to reference throughout the planning process. In cases where a supply chain map has never been developed before, its uses are many and go well beyond the hazard assessment process.

When reviewing a completed supply chain map, the very use of the term “supply chain” seems open to discussion. Looking at all the complex ins and outs, tiers, and dependencies, we may wonder if what we are really dealing with is actually not a supply chain but a business network or a supply chain maze or web. This visual description of the supply chain can lead to a more accurate and common understanding of the complexities of the supply chain for those who develop the map, as well as for others across supply chain functions and throughout the enterprise.

Quantifying Identified Risks

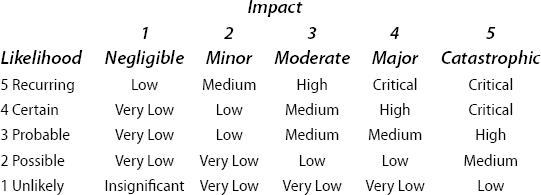

Once all possible hazards are listed, they must be quantified to prioritize the need to mitigate against and manage them. There are many ways to analyze the identified risks. For example, the risks can be graphed. (See Figure 3-2.) Another tool is the hazard assessment matrix, shown in Figure 5-2. This is a similar approach that quantifies each hazard based on two factors: the probability it will occur and the impact it will have should it occur.

For example, for a company located near a fault line in the San Francisco Bay Area, the probability of experiencing an earthquake of 5.0 or greater on the Richter scale might be rated as a probability of 3–probable with an impact of 5–catastrophic, based on factors such as exact location and the seismic rating of the company’s buildings. This combination of probability and impact indicates a high level of risk requiring that mitigation measures and plans be implemented to manage the threat.

FIGURE 5-2.

HAZARD ASSESSMENT MATRIX.

A similar way to classify threats is to put them in categories based on the level of risk it is determined each represents. For example:

![]() Level 1 Risk. One that is limited in scope and impact

Level 1 Risk. One that is limited in scope and impact

![]() Level 2 Risk. One that is moderate in scope and impact

Level 2 Risk. One that is moderate in scope and impact

![]() Level 3 Risk. One that is catastrophic, widespread in scope with long-term consequences

Level 3 Risk. One that is catastrophic, widespread in scope with long-term consequences

Applying this approach, Level 3 risks become the primary focus of mitigation and planning efforts, then Level 2, and finally Level 1 as deemed necessary.

Still another approach to analyzing vulnerabilities involves a point system. Each identified threat is scored based on five factors. Four of these use a scale of 5 to 1, with 5 being the highest and 1 the lowest. The four factors are:

1. Probability of occurrence

2. Impact on people

3. Impact on facilities and equipment

4. Impact on operations

A fifth score from 1 to 5 is given to the resources currently in place to respond to and recover from the threat should it become a reality. To score existing resources, 5 indicates that current resources are insufficient, while 1 indicates that resources currently in place are sufficient.

The five scores are totaled for each listed threat. Those with the highest scores are the ones that get the most immediate attention in the form of mitigation and planning.

Again using the San Francisco Bay Area earthquake threat example, the probability of a 5.0 or greater earthquake impacting the company is likely 3, the impact on people should an earthquake occur is 4, the impact on facilities and equipment 4, the impact on operations 4. The available resources score can vary greatly. Let’s say the company has secured all office furniture, shelving, and equipment, the building is built to earthquake-resistant standards, there are trained employee response teams, a mature business continuity program in place, and redundant operations at another company location. Based on these resources, the fifth score is 2. Using this methodology, the total score for an earthquake event is 17 out of a possible 25 points.

Once the potential threats to continued operations are identified and quantified, an assessment is made of the short-term, mid-term, and long-term effects of the identified hazards on operations. This is done by using a scenario as a planning tool. A scenario is a brief narrative describing the hypothetical situation and conditions and the likely future when a destructive or disruptive event occurs. Based on the results of the hazard assessment, select an identified hazard and begin the process of considering the what-ifs should the disaster actually occur. Then, discuss the impact the disaster would have on your facilities, employees, and operations, as well as whether there would be supply chain interruptions and the possibility of delays in meeting customers’ requirements. Using planning scenarios goes well beyond simply identifying risks and delves into the effects a given disaster would have on the organization.

Avoiding Inherited Risks

Risks can be inherited from suppliers, contractors, and the companies to which we outsource. In the past, cost and quality were the primary deciding points in selecting these important partners. With today’s trend of fewer suppliers, each becomes more important, and the ability of each to meet customer requirements is increasingly vital.

To avoid the possibility of taking on unwanted inherited risks, it is essential to add consideration of the ability of these external suppliers to continue to meet obligations when faced with a disaster. While there may be a misconception that outsourcing transfers risk, the actuality is that outsourcing brings inherited risks and results in less direct control of managing those risks. Consider the unplanned loss of the services provided by a company to which you outsource and the accompanying impact on your company should there be a complete or partial loss of these services. If the service provider is a sole source provider—a single point of failure—then the potential is a total loss of critical service. If the provider has no business continuity plan and you have no contingencies for temporarily filling the gap internally and no alternate provider, then the potential risks are great and require action.

The level of scrutiny given to each of these companies is determined by the criticality of each company’s input to your processes and how easy or difficult it may be to replace the supplier, vendor, outsourcer, or service provider should it be necessary. Trite but true: A chain involving a maze of business partners, service providers, third-party suppliers, and customers is only as strong as its weakest link, particularly when we are at the mercy of a sole source provider. Managing continuity risks in the supply chain is a process that inevitably involves working with these third parties to plan, execute, and monitor continuity strategies. Responsibility for supplier evaluation and selection is generally managed by the purchasing/procurement function. (This is discussed in Chapter 7.)

Applying the Hazard Assessment to Develop a Mitigation Program

Once hazards are identified and quantified to prioritize the greatest risks, a determination is made as to how best to manage, or mitigate, each risk. One of the four elements of a comprehensive business continuity program, mitigation is the ongoing actions taken in advance of a destructive or disruptive event to reduce, avoid, or protect against its impacts. Three choices for proactively managing any risk are:

1. Mitigate the risk by some means, such as contracting with alternative suppliers or developing alternate freight routing plans.

2. Transfer the risk to someone else, such as an insurance company, by adding or increasing insurance coverage.

3. Accept the risk by making a proactive decision to absorb any resulting financial losses.

A fourth alternative, though one that is not recommended, is to simply ignore the risk and hope it will go away. While this is an option, the reality is that left uncontrolled, supply chain risks threaten a company’s financial health and brand reputation and can result in a loss of sales and—even more damaging—a loss of customers, resulting in long-term damage to the organization and its success.

Creating a Solid Foundation for Business Continuity Planning

While it is not possible to anticipate or predict all potential disasters or the full impact a catastrophic event can have on an organization, a hazard assessment is critical and has a significant effect on the ultimate success of business continuity planning efforts. Identifying all commonly considered threats and those that are unique to your company, together with the probability of each actually occurring, goes beyond simply considering disasters in the classic sense. The process gives full consideration to operational risks including those found in all segments of the supply chain. Equally important is the role of a hazard assessment in gaining an in-depth understanding of the magnitude of the disruption each threat can have on all areas of the business and the resulting ability to meet customer needs.

This quantitative, documented approach to analyzing risk leads to better informed continuity planning decisions and provides guidance for where best to focus mitigation and planning efforts and funding.

The hazard assessment combined with a business impact analysis provides a solid foundation for building a successful business continuity program tailored to the specific needs of the organization.

Going Forward

A hazard assessment is an invaluable tool in developing a program for protecting an organization and its supply chain against risk. Gaining a thorough understanding of the vulnerabilities and the related impact to the business provides information necessary for implementing appropriate mitigation strategies and lays the groundwork for the development of a valuable and realistic business continuity program.

![]() If a hazard assessment was previously conducted, determine whether supply chain–specific risks were included in the process.

If a hazard assessment was previously conducted, determine whether supply chain–specific risks were included in the process.

![]() Conduct a hazard assessment of the supply chain. Involve representatives of all supply chain business units.

Conduct a hazard assessment of the supply chain. Involve representatives of all supply chain business units.

![]() Link the results to the company’s ability to produce and deliver its product or service.

Link the results to the company’s ability to produce and deliver its product or service.

![]() Identify possible low-cost mitigation measures that can be implemented immediately.

Identify possible low-cost mitigation measures that can be implemented immediately.