6.

FROM OPERATIONAL TO STRATEGIC AGILITY

Having a strategy suggests an ability to look up from the short term and the trivial to view the long term and the essential, to address causes rather than symptoms, to see woods rather than trees.

—LAWRENCE FREEDMAN1

As the Agile mindset and processes increasingly enter the management mainstream, firms are learning how to draw on the full talents of those doing the work, involve customers at every stage of product development, and generate innovations that customers value.

While most organizations implementing Agile management are still preoccupied with upgrading existing products and services through cost reductions, time savings, or quality enhancements for existing customers (i.e., operational Agility), they need to realize that the major financial gains from Agile management will flow from the practice of Strategic Agility—that is, generating innovations that create entirely new markets by turning noncustomers into customers. Strategic Agility is the next frontier of Agile management.

Transformation “confuses three fundamentally different categories of effort,” writes Scott Anthony, managing partner of Innosight:

The first is operational, or doing what you are currently doing, better, faster, or cheaper. Many companies that are “going digital” fit in this category—they are using new technologies to solve old problems. . . . The next category of usage focuses on the operational model. Also called “core transformation,” this involves doing what you are currently doing in a fundamentally different way. Netflix is an excellent example of this type of effort. . . . The final usage, and the one that has the most promise and peril, is strategic. This is transformation with a capital “T” because it involves changing the very essence of a company. Liquid to gas, lead to gold, Apple from computers to consumer gadgets, Google from advertising to driverless cars, Amazon.com from retail to cloud computing, Walgreens from pharmacy retailing to treating chronic illnesses, and so on.2

Don’t get me wrong, operational Agility is a good thing. In fact, it’s an increasingly necessary foundation for the survival of a firm. And it’s also a precondition for achieving Strategic Agility. But in a marketplace where competitors are often quick to match improvements to existing products and services and where power in the marketplace has decisively shifted to customers, it can be difficult for firms to monetize those improvements. Amid intense competition, customers with choices and access to reliable information are frequently able to demand that quality improvements be forthcoming at no cost, or even lower cost.

Efficiency gains, time savings, and quality improvements operate within a limited frame. “The conventional view of the competitive landscape,” as Clayton Christensen and his colleagues explain in their book Competing Against Luck, “puts tight constraints around what innovation is relevant and possible, as it emphasizes bench-marking and keeping up with the Joneses. Through this lens, opportunities to grab market share can seem finite, with most companies settling for gaining a few percentage points, within a zero-sum game.”3

“We tend to confuse capitalism with competition,” writes David Brooks, citing Peter Thiel, the creator of PayPal and author of From Zero to One. “We tend to think that whoever competes best comes out ahead. In the race to be more competitive, we sometimes confuse what is hard with what is valuable. The intensity of competition becomes a proxy for value. Instead of being slightly better than everybody else in a crowded and established field, it’s often more valuable to create a new market and totally dominate it. The profit margins are much bigger, and the value to society is often bigger, too.”4

This is the dark secret of the Agile management revolution: The major financial gains will come from Strategic Agility—namely, through mastering market-creating innovation.

Market-creating innovations are innovations that open up markets that didn’t previously exist.

![]() Sometimes they transform products that are complicated, inconvenient, and expensive into things that are so much more affordable, convenient, and accessible so that many more people are able to buy and use them—for example, the personal computer.

Sometimes they transform products that are complicated, inconvenient, and expensive into things that are so much more affordable, convenient, and accessible so that many more people are able to buy and use them—for example, the personal computer.

![]() Sometimes the new products meet a need that people didn’t realize they had and create a “must-have” dynamic for customers, even though the product may be relatively expensive—for example, Starbucks coffee or the iPhone.

Sometimes the new products meet a need that people didn’t realize they had and create a “must-have” dynamic for customers, even though the product may be relatively expensive—for example, Starbucks coffee or the iPhone.

Market-creating innovations usually don’t come from resolving customer complaints or asking existing customers what they want. As Henry Ford allegedly said, if he had asked customers what they wanted they would have said a faster horse.5 Market-creating innovations come from imagining and delivering something that delights whole new groups of customers once they realize the possibilities. Thus, no one was pressing Silicon Valley to create the personal computer, or Apple to create the iPhone, or Starbucks to create a billion new flavors of coffee. Those firms delivered something that surprised and delighted customers, once they experienced it. The product itself created the demand.

Market-creating innovations are where major revenue growth comes from. That’s because they lead us to the so-called blue oceans of profitability, as W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne explain in Blue Ocean Strategy.6 An organization can generate high growth and profits by creating value for customers in uncontested market spaces (“blue oceans”), rather than by competing head-to-head with other suppliers in bloody shark-infested waters with known customers in existing markets (“red oceans”). By looking at the world from the customer’s point of view, a firm doesn’t find new ways to delight the customer: It creates them.

![]() Thus, the Cirque du Soleil was able to enter an apparently dying industry—circuses—and by eliminating animal acts, deemphasizing individual stars, and combining extreme athletic skill with sophisticated dance and music, it created the largest theatrical company in the world. While traditional circuses were going out of business, the Cirque du Soleil flourished.

Thus, the Cirque du Soleil was able to enter an apparently dying industry—circuses—and by eliminating animal acts, deemphasizing individual stars, and combining extreme athletic skill with sophisticated dance and music, it created the largest theatrical company in the world. While traditional circuses were going out of business, the Cirque du Soleil flourished.

![]() By looking at the world from the customer’s point of view and finding ways to delight the customer, Apple has been able to take “mature” low-margin sectors—retail computers, music, mobile phones, and tablet computers—and turn them into huge money-makers. In the process, Apple, which was practically bankrupt in 1997, now has one of the world’s largest market capitalizations.

By looking at the world from the customer’s point of view and finding ways to delight the customer, Apple has been able to take “mature” low-margin sectors—retail computers, music, mobile phones, and tablet computers—and turn them into huge money-makers. In the process, Apple, which was practically bankrupt in 1997, now has one of the world’s largest market capitalizations.

In the world of Strategic Agility, we have learned that there is no such thing as a mature industry: There is only an industry to which imagination has yet to be applied.

The Principles of Strategic Agility

Strategic Agility occurs in two main ways: either as a by-product of operational Agility or as explicit initiative to generate market-creating innovation.

By-Product of Operational Agility

At Spotify, Discover Weekly was a feature intended to solve a known problem with an existing product: the difficulty that existing users were having in locating music that they would truly love, in Spotify’s vast library of millions of songs. Discover Weekly not only solved that problem for existing users, but the innovation was so successful that it brought in tens of millions of new users and became in effect a brand in itself. In some countries, Discover Weekly playlists are better known than Spotify itself.

Spotify’s approach to innovation is mainly based on the lean-startup principle that considers the biggest risk in innovation to be that of building the wrong thing. To reduce this risk, you start by imagining what you have in mind. Then you check whether any customer would want it. Then you build a prototype. Then you go on tweaking it, adding features that may help to monetize what you have built.

Before deciding to build a new product or feature, the teams inform themselves with research. “Do people actually want this? Does it solve a real problem for them?” Prototypes are built to give everyone a sense of what the feature might feel like and how the people might react.

Once they feel confident that the idea is promising, they go ahead and build a “minimum viable product”—just enough to fulfil the narrative, but far from being a completed product. When it is released to just a small percentage of all users, they use tools like A/B testing to monitor impact.7 They keep adjusting the feature until they see the desired impact. Then they roll it out to the rest of the world while sorting out operational issues, like languages and scaling. In this way, Discover Weekly turned into a huge win, attracting tens of millions of new users for Spotify.

While this approach can work well in terms of improving existing products for existing users, it has several limitations in terms of systematically generating market-creating innovations.

First, in an ongoing organization as opposed to a startup, Agile teams are inevitably focused on making things better for existing users. If the improvement creates new markets of nonusers, that is a happy accident, not the main goal. To get more consistent success in generating market-creating innovations, explicit attention to nonusers is needed.

Second, market-creating innovations sometimes involve eliminating features, not adding or improving them. Paradoxically, less may be more. Thus, a firm may generate market-creating innovation by eliminating elements that it or other firms are marketing as high value for customers. The resulting simplification can sometimes perform the dual function of lowering costs and drawing in vast numbers of new users. A classic case is Southwest Airlines, which based its business on eliminating the very features the rest of the airline industry were trumpeting: meals, lounges, and seating choices.

As professors W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne point out in Blue Ocean Strategy:

Southwest offered high-speed transport with frequent and flexible departures at prices attractive to the mass of buyers . . . the company emphasizes only three factors: friendly service, speed, and frequent point-to-point departures . . . it doesn’t make extra investments in meals, lounges, and seating choices. By contrast, Southwest’s traditional competitors invest in all the airline industry’s competitive factors, making it much more difficult for them to match Southwest’s prices.8

Southwest also made strenuous efforts to create genuine teams that had fun working together and with customers. For many customers, fewer features and lower prices, plus friendly and timely service, add up to a package that is a better deal.

Yet the decision to eliminate seemingly popular features is not one that is easily taken at the level of the Agile team. Agile teams are generally focused on responding to requests from existing customers—typically adding something that is missing. Teams are unlikely to propose or carry out experiments to eliminate key features that would bring in new customers, since it is usually assumed that even features being used by only a few existing customers must be valuable to them. Moreover, existing features typically have their own constituencies within the organization, so a team that has created a feature often becomes the champion for retaining and improving it. Unless there is an explicit decision at a higher level to consider eliminating features with the goal of attracting new noncustomers, it is unlikely to happen. Even then, it may not work. Thus, United Airlines had difficulty emulating Southwest’s low-cost model with its spin-off Ted, in part because of internal lobbies to keep running the airline the way it has always been run.

Third, market-creating innovations can lead to cannibalization of the firm’s existing products and so generate a reluctance to interfere with a current revenue stream. Thus, it wasn’t an easy decision within Apple to include a music-playing capability in the iPhone because it cannibalized the market for the iPod. Initially, Steve Jobs himself opposed it. But then came the realization that if Apple didn’t disrupt itself, some other competitor would. Thus, Apple decided to sacrifice the revenue stream from the iPod in favor of the larger potential gains from the iPhone. Such a decision is never easy and typically it has to be taken at the highest levels of the organization.

Fourth, if corporate incentives flow to those who can show immediate results from improving an existing product for existing customers, then any slow-moving “big bets” under consideration will tend to morph into “small bets” that generate quick wins. The pressure to “get results now” will make it harder to attract top talent to work on expensive slow-gestating investments that could have huge gains. To overcome these tendencies, top management must underline the importance of winning “big bets,” even if their gestation is slow, and create specific incentives to bring them to fruition.

Finally, work on improving existing features can be suitable for low-investment market creation, as at Uber and Airbnb. But it’s rarely a solution for innovation that requires substantial technical innovation. Lean-startup thinking is not well suited to deal with decisions on market-creating innovations involving large investments in a new product, when no one knows in advance what the eventual product or service will look or feel like or even whether the idea will work. Often, it isn’t possible initially to put a prototype in front of potential users and see whether they will use it and be thrilled by it. In most cases, there will be no “hard data” on which to base a decision. When the firm is imbued with lean-startup thinking, the firm often ends up pursuing a series of “small bets” to the neglect of “big bets.”9

In the absence of a systematic approach to fostering market-creating innovation, decisions on such large investments will often turn on corporate politics: The loudest voice having the most hierarchical clout will end up making the call. In the absence of hard numbers, proceeding with the investment will often be perceived as presenting too great a risk and the investment will be abandoned. If a decision is finally made to go ahead with investing in a capital-intensive innovation after a bruising battle at the top, it can be hard for the organization to change course even if actual data starts to show that the firm is on the wrong track. In such situations, the firm may continue to invest in a losing proposition until it turns into a disaster that is too obvious to ignore.

Yet it doesn’t have to be this way. There are well-established principles that can lead to sustained success with market-creating innovations. They involve understanding the art and science of Strategic Agility.

Market-Creating Value Propositions

A systematic approach to Strategic Agility is needed to create new markets for products or services that will enjoy strong demand and growth from both customers and noncustomers. The aim is to create products or services that enjoy little competition, precisely because they meet a need in the marketplace that is currently not being met—the so-called blue oceans of profitability.

Market-creating value propositions involve a shift in thinking from the known to the unknown—from existing products to new products—and from existing users to nonusers of the firm’s products. This in turn means redefining how needs are being met and, in the process, discovering value for both customers and noncustomers from elements that lie outside current thinking, both within the firm and within the industry.

It also means a change from thinking of the outputs of the organization to considering outcomes for the customer or end-user. “Instead of thinking of your company as providing a particular type of product or service—electric power, health records management, or automobile components,” writes PricewaterhouseCoopers consultant Norbert Schwieters, “think of it as a producer of outcomes. The customer needs to get somewhere, so you’re not a car company; you’re a facilitator of that outcome. The house is cold, so you help make it warm, possibly without supplying the necessary fuel. . . . Customers, in turn, are making fewer purchases to accumulate physical things and more purchases to achieve outcomes, convenience, and value.”10

In considering outcomes, the firm has to be thinking more broadly than the primary function that the product or service is currently performing. Take, for instance, an airline flight. At its most basic, the airline is delivering passengers from airport A to airport B. But there are many other aspects of the customer’s experience that go beyond that. It includes the experience of the customers in getting from wherever they are to airport A, and in getting from airport B to wherever they want to get to eventually. It includes the experience of getting from the front door of the airport to getting inside and sitting down in the plane, including checking in and going through security checks and baggage handling. It includes the experience of what happens on the plane in terms of the services provided, with passengers wanting comfort, convenience, and the ability to do whatever they want to do on the flight—work, rest, or be entertained. It includes the quality of the interaction with the airline staff and the other passengers. It includes services that may be taken for granted such as reliability and timeliness, as well as how problems are handled, such as weather problems, flight delays, overbooked flights, or misplaced luggage. It may include intangible deliverables, such as whether the airline or the class of service is “cool.”

Thus, the outcome of even an apparently simple thing like an airline flight is in fact a complex set of many interacting elements that make up the overall experience or outcome in the customer’s mind. Care needs to be taken when using language like “the job to be done,” which may be taken as pointing to the primary deliverable but may miss the other kinds of customer value.

In their book Competing Against Luck, Christensen and colleagues argue against “defining customer needs through typical market research and then delivering against them.” This can lead to a focus on “functional needs without taking into account the broader social and emotional dimensions of a customer’s struggle. . . . And in many cases emotional and social could be on the same plane as functional needs—and maybe even be a driver.”11 For example, the Rolex watch is a status symbol and most of its value is based on intangible deliverables.

Outcome-oriented decision making also means a shift in thinking from looking at the industry as currently conceived. Sector boundaries as we knew them in the twentieth century are collapsing. (See Box 6-1.)

Four Components of a Market-Creating Value Proposition

A helpful playbook for developing a market-creating value proposition was pioneered by Curt Carlson and his colleagues at the Silicon Valley icon SRI International, where Carlson was president and CEO from 1999 to 2014. It is described in his book Innovation: The Five Disciplines for Creating What Customers Want.12 The Innovation-for-Impact Playbook describes an organizational design and value-creation process for creating major breakthroughs, as SRI International did with HDTV, the Intuitive Surgical spin-off, and Siri, among many other developments.13

The playbook from SRI offers a concise but complete definition for a value proposition. There are four components—Need, Approach, Benefits per costs, and Competition—that are summarized in the mnemonic NABC. “They are the fundamentals,” says Carlson. “It doesn’t make sense to write up a big report until you can explain them in simple language to a knowledgeable person. Once those fundamentals are in place, the full business plan is much more efficiently developed.”

Identify the Need

It begins with a focus on outcomes and the customer’s need, not the firm’s need for a new product or a shareholder’s need for value. “Does the customer have a need for something?” writes Anand Venkataraman, a colleague of Carlson’s at SRI. “How acute is this need? Would a solution be a lifesaver, a painkiller, or a supplement? Furthermore, how can you quantify the need? Is the need relevant to one person, a few people, or an entire demographic? . . . The first thing you do is to record the need as you see it and determine just how big the scope is. If it’s not large enough (doesn’t impact a significant number of people) can it be made to? These questions can’t be answered and refined until after you’ve quantified the need. So as a first step, write down a tentative number on how big you think this need is.”14

Understand noncustomers. “Obviously, the first port of call should be the customers,” write the authors of Blue Ocean Strategy. “But you should not stop there. You should also go after noncustomers. And when the customer is not the same as the user, you need to extend your observations to the users. . . . You should not only talk to these people but also watch them in action. Identifying the array of complementary products and services that are consumed alongside your own may give insight into bundling opportunities. Finally, you need to look at how customers might find alternative ways of fulfilling the need that your product or service satisfies.”15

Study markets. Although there is a lot of attention on global markets for products such as smartphones, most markets are fragmented in narrow segments. It can be a mistake to chase a single narrow market niche. What you need is a product or service that addresses a collection of narrower market segments. Market-creating innovation implies moving into markets that are bigger than the firm’s current market.

The Approach

“It’s all about how you solve this particular need of the customer,” writes Venkataraman. “Here is where you’ll ask yourself what your secret sauce is. It’s important to have a secret sauce because that’s what tells you how innovative your original idea is. Besides, a secret sauce is your entry barrier. A successful company needs an entry barrier to give it an opportunity and a kind of monopoly and incentive to develop its idea to its fullest. Without an entry barrier, rather than focus on refining the core of the idea at a time when it’s needed most, you would be expending all your energy on deterring others from eating your lunch. Instead of simplifying your idea, which is the key to success, you’ll end up making it more complex which spells certain doom.”16

Think platforms. “What happens with companies that have successfully externalized,” says Haydn Shaughnessy, “is that they manage to lay off a lot of the burden of change onto their ecosystem. That frees management to make decisions without having to think about all the issues of scaling the base. If you think about Apple, they were able to grow an ecosystem of somewhere in the order of 500,000 developers. This meant that management wasn’t faced with the administrative burden of investing in growing an army of internal developers that made Apps. This kind of externalization relieves the burden of managing scale and enables very rapid scaling.”17

As Schwieters writes, “The race is now on to develop and expand the platform ecosystems to deliver such outcomes for many different sectors. Amazon already provides a platform for sellers to use. Leading companies are strengthening their positions as platform providers in a wide range of industries—GE and Siemens, for example, have each developed a cloud-based system for connecting machines and devices from a variety of companies, facilitating transactions, operations and logistics and collecting and analyzing data.”18

Acquire digital competency. Traditionally, adjacent moves were perceived as risky and firms were advised to stick to their core business. Once firms acquire competency in handling very large amounts of data and operate in a network fashion, they become able to make quite radical adjacency moves, as at Amazon. As a result, the idea of a core business itself is no longer static and fixed. Instead, a fluid core enables moves into new sectors, growing competency very quickly.

Have a bias for action. “I used to attend conferences in Europe where Nokia people would talk about the digitization of everyday life,” says Shaughnessy. “It was fascinating because this was 2005. They were talking about how we would end up digitizing absolutely everything. The problem is that it was Facebook that connected people. It was Google that sold the ads on the Web, and it was Apple that made the smartphone. So for all its knowledge, Nokia didn’t execute. It comes back to the business of managing adjacencies. What Nokia needed to do in 2005 was to commit to its vision of the world. It had a fabulous vision. But all it did with its vision was to carry on making phones with keyboards.”19

Build on an existing strength. John Hagel gives the example of State Street Bank. It “started as a very conventional retail bank. It was founded in 1793. In the 1970s, it faced increasing pressure in its core business. A C-suite executive realized that they needed to find a different way of doing business and came up with the idea of renting out some of their transaction processing capabilities to other banks, who were facing similar pressure. It met a need in the marketplace and they scaled that very rapidly. Over time, they walked away from their traditional core business. It gave them a new way to define their business, their processes and operations, their approaches, and their culture. It served them well.”20

Scale. The firm will also need the capabilities to operate at scale. The idea must be more than “interesting”; it must relate to a market that is sufficiently large to warrant the investment, along with the potential capability to cope with a large market. Thus, when Apple made its move into mobile phones, it had to have an enormous transaction engine capable of dealing with billions of transactions in a year.

Benefits per Costs (for Both the Customer and the Producer)

Writes Venkataraman:

This tells you not only what improvement your solution will make in the life of the customer, but also how much of a difference. It’s important to understand that almost every significant benefit can be quantified, even if only by proxy. Sometimes we may consider benefits that seem vague and think that it’s impossible to quantify them, but that’s only because we haven’t yet got the discipline to look at them closely enough. We give in to the euphoria of having identified a need and run with it without critically examining it. Or we give in to the fear that if we looked at it too closely it might turn out there wasn’t really a need after all. Discipline gives us the courage to transcend the fear and the willpower to resist this premature euphoria.

With patience, perseverance and practice we will learn to identify things in a customer’s life that are inherently valuable. It doesn’t always (rarely, in fact) boil down to the number of dollars a person would save by using an invention. Often the quantification of a benefit may be in terms of intangible but yet quantifiable things—for example, increasing the number of hours of their free time that they would spend with family and friends or on their hobbies, the number of words they have to use to communicate a particular idea, the amount of effort expended (in footsteps or calories, for instance) to get to a certain place, or the number of minutes one could be continuously immersed and engaged in an entertaining or other valuable experience. It may even be some combination or collection of multiple benefits, each of which has its own quantification cell. The important thing is to get this down, and not worry about putting down something incorrect because you will get numerous chances to go back and revise it. Remember that NABC [need, approach, benefits per costs, and competition] is an iterative framework.21

From the producer’s perspective, the financial benefits compared to costs must also be positive, even if the gains take time to materialize. A mere hope that a path to monetization will somehow show up is not enough. A potential path to monetization must be thought through from the outset.

There may be indirect ways of achieving financial benefits for the producer without compromising the user experience, by distinguishing the user and the customer (see Box 3-2). For instance, Google search is free, but huge financial benefits accrue to Google through data-focused advertising. The service provided to users feels costless and frictionless, since the monetization of benefits for Google is happening in the background.

Competitors and Alternatives

Venkataraman further writes:

This is what others are and could be doing to address the same need you have identified. Many times young innovators are bound to think that their idea is so radical that there exists no competition. But that’s a mistaken notion. Every idea and proposal has competition if we look at it closely enough. I appreciate that an empty slate is hard to get started on, so here’s at least one competitor you can write down for any possible idea . . . your first competitor is the prospect that users will simply continue to do whatever they’ve been doing in the past to address that need. The number one competitor to your invention is the alternative of not having it.

The source of the difficulty that most people have in identifying competition is that they always think of their approach and not the need when trying to find competitors. It’s understandable that the approach takes center stage, of course, because that’s where your secret sauce is—the thing of value you bring to the table, and naturally the thing you feel the greatest affinity for. But to really understand your competition, the NABC framework teaches you to step back and give up being intoxicated by the coolness of your approach for a bit. Think of the need and try to make a list of everything anyone is or could be doing to address the need. Don’t think “Who else is using the same or similar approach as mine to meet that need?” but think “What have people done or could do to meet this need?” If you came up with the idea of sticky tape as a way to fix notices to doors, don’t only think of glue as your competitor. Think of thumbtacks, chalk, email, Facebook, and Twitter as competition.

Once you identify and make a list of the competitive approaches as exhaustively as you can, your own approach will now be one of those in the long list. You can now start enumerating the pros and cons of each approach quantitatively. Does a particular competitor reach the same users (market) as your idea will? Does it offer the same benefits? Is it cheaper or more expensive to make? And so on. If the answer to any of these questions is unfavorable, this is your chance to go back and see if either the need or the approach can be adjusted to accommodate this shortcoming. Feel fortunate that you found this issue now, before investing thousands, if not millions, of dollars into productizing your originally short-sighted idea.22

Continue to Iterate

“When you’ve looked at all four components of the NABC once,” says Venkataraman, “you go back and revisit the Need again, repeating the whole process as many times as needed. Chances are that your original thoughts on what you believed to be the need has changed. So you revise it.” Just like a scientific theory, he says, “You start with the original need, and after having gone through one cycle of analysis, you come back and augment it to account for its shortcomings. You may patch it up here and there, or make fundamental changes. But the bottom line is that as long as the customer’s need is genuine . . . every failed attempt to take it down would only have made it stronger by fortifying its weak spots. So if nothing else, the NABC practice promises to at least strengthen your value proposition.”23

For most organizations, implementing NABC propositions will be an important shift in the organizational culture. As Carlson notes, “NABC value propositions apply to every position in a company. The framework is simple and fundamental. Having every conversation in the company start with the customer’s needs is transformational.” To get an idea of what this involves, Chapter 7 will cover Carlson’s account of his sixteen-year stint as president and CEO of SRI International and the organizational culture change that he led.

THE COLLAPSE OF SECTOR BOUNDARIES

A 2016 PwC report, “The Future of Industries: Bringing Down the Walls,”1 documents how the boundaries among sectors are dissolving. “The pace of technological change is creating at least the prospect of a new industrial order, in which most companies no longer operate within the comfort zones of their established sectors. Already, a few companies—Apple, Amazon, and GE, among them—have boldly and successfully moved into new industries. Now just about every other company will have to do business that way.”2

The report cites examples of whole sectors being redefined and reinvented:

![]() Telecommunications. Telecom companies used to be in the business of routing calls and data. But now, they are becoming entertainment content companies.

Telecommunications. Telecom companies used to be in the business of routing calls and data. But now, they are becoming entertainment content companies.

![]() Automakers. The future of car manufacturing will be facilitating mobility on demand. Consumers will order cars from mobility services to suit their immediate needs.

Automakers. The future of car manufacturing will be facilitating mobility on demand. Consumers will order cars from mobility services to suit their immediate needs.

![]() Electric utilities. The staid industry of power generation is facing a future of smart infrastructure. It begins with security and temperature control, and expands to embrace a diverse range of integrated and automated services, including larger-scale energy management, monitoring of building maintenance, city resource management, transportation efficiency, and eldercare.

Electric utilities. The staid industry of power generation is facing a future of smart infrastructure. It begins with security and temperature control, and expands to embrace a diverse range of integrated and automated services, including larger-scale energy management, monitoring of building maintenance, city resource management, transportation efficiency, and eldercare.

![]() Hardware. The Internet of Things (IoT) is transforming hardware, as firms can add sensors to their products to enable predictive maintenance and other forms of security and monitoring.

Hardware. The Internet of Things (IoT) is transforming hardware, as firms can add sensors to their products to enable predictive maintenance and other forms of security and monitoring.

![]() Health care. Here, too, IoT is leading to the use of sensors to provide data that health professionals can use to provide early diagnostic or real-time follow-up services.

Health care. Here, too, IoT is leading to the use of sensors to provide data that health professionals can use to provide early diagnostic or real-time follow-up services.

![]() Personalized services. The IoT will greatly intensify the focus on outcomes, convenience, and value. In consumer products manufacturing, for example, the IoT makes it possible to get feedback directly from consumers.

Personalized services. The IoT will greatly intensify the focus on outcomes, convenience, and value. In consumer products manufacturing, for example, the IoT makes it possible to get feedback directly from consumers.

![]() 3D printing. Digital fabrication will make it possible to build everything from airplane parts to garden ornaments.

3D printing. Digital fabrication will make it possible to build everything from airplane parts to garden ornaments.

Thus, companies in all industries need to be ready to stretch their horizons beyond their existing businesses. “This doesn’t necessarily mean the borders will disappear between all industries,” writes Schwieters. “But if you are a business leader, you should expect your company’s sector to be transformed, probably within a decade, by the shockwave of technology change that is upon us.”3

NOTES

1. PricewaterhouseCoopers, “The Future of Industries: Bringing Down the Walls,” PwC’s Future in Sight Series, 2016, http://www.pwc.com/gx/en/industries/industrial-manufacturing/publications/pwc-cips-future-of-industries.pdf.

2. N. Schwieters, “The End of Conventional Industry Sectors,” strategy + business, January 3, 2017, https://www.strategy-business.com/blog/The-End-of-Conventional-Industry-Sectors.

3. Ibid.

THE PATH FROM OPERATIONAL AGILITY TO STRATEGIC AGILITY

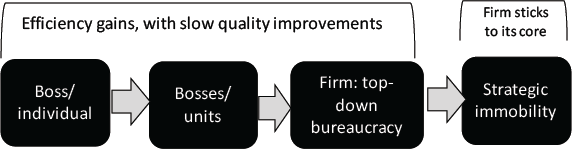

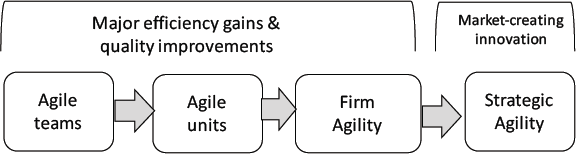

The journey toward Strategic Agility involves a natural progression.

![]() A firm may start experimenting with one or more teams with operational Agility, even though the firm as a whole lacks operational Agility (see Figure 6-1).

A firm may start experimenting with one or more teams with operational Agility, even though the firm as a whole lacks operational Agility (see Figure 6-1).

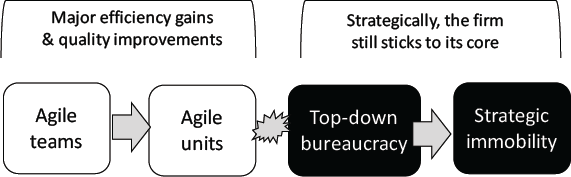

![]() As more and more teams take on Agile management, eventually a whole unit embraces Agile (see Figure 6-2).

As more and more teams take on Agile management, eventually a whole unit embraces Agile (see Figure 6-2).

![]() Then the whole firm, or a large unit, may embrace Agile management with major enhancement of the capacity to make quality improvements and efficiency gains (see Figure 6-3).

Then the whole firm, or a large unit, may embrace Agile management with major enhancement of the capacity to make quality improvements and efficiency gains (see Figure 6-3).

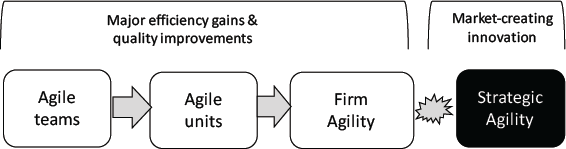

![]() Finally, the newfound operational Agility at the enterprise level may then evolve toward Strategic Agility with a capability to open up new markets (see Figure 6-4).

Finally, the newfound operational Agility at the enterprise level may then evolve toward Strategic Agility with a capability to open up new markets (see Figure 6-4).

The path to strategic Agility thus passes through operational Agility. Today, many firms are still learning how to achieve operational Agility at the team and unit level. They have yet to achieve full operational Agility (Figure 6-3), let alone Strategic Agility (Figure 6-4).

Surveys carried out by the SD Learning Consortium show that 80 to 90 percent of Agile teams currently perceive tension between the way the Agile teams function and the way the whole organization operates. Unless the tension is resolved, it can lead to abrupt abandonment of an organizational commitment to Agile altogether, with the firm declaring disingenuously that “we are already Agile,” only to be followed by the recognition of the sad reality shortly afterward, and a fresh effort to “implement Agile.” The full gains of operational Agility only come when the whole firm embraces Agile management.

Figure 6-1. Twentieth-century top-down bureaucracy.

Figure 6-2. Operational Agility at the team/unit level.

Figure 6-3. Operational Agility at the enterprise level.

Figure 6-4. Operational and Strategic Agility.

Achieving operational Agility is necessary, but it may not be sufficient to achieve financial sustainability. Even firms that achieve full operational Agility still have another frontier to master: Strategic Agility.

Operational Agility is nevertheless a crucial precondition of achieving Strategic Agility. Unless the firm is able to rapidly iterate on its market-creating initiative in accordance with the Law of the Small Team, the Law of the Customer, and the Law of the Network, there is little prospect that the market-creating initiative will succeed.