Chapter 21

Specific Corporate Governance Issues in Islamic Banks

1. INTRODUCTION

Prior to the recent financial crises there was already a growing interest in the corporate governance of banks (Caprio and Levine 2002; Charkham 2003; Levine 2003; Macey and O’Hara 2003). Not surprisingly, this interest has grown further following the crises (Dermine 2011; Kirkpatrick 2009; OECD 2009; Peni and Vähämma 2011).

Banks, like any other organisation, have a number of stakeholders, such as shareholders and debt holders, as well as boards of directors, competitors, and so on. This suggests that the need for a separate analysis of the corporate governance of banks is not self-evident and requires justification. However, the occurrence of the crises supports the view of those (e.g., Charkham 2003, 15) who argue: “Banks are different from the generality of companies in that their collapse affects a far wider circle of people and moreover may undermine the financial system itself, with dire effects for the whole economy.” Further, Caprio and Levine (2002) and Levine (2003) identify three characteristics that they claim warrant an independent discussion of the governance of banks. They argue that banks are generally more opaque than other financial institutions, which fundamentally intensifies the agency problem. Second, banks are exposed to heavy regulation. Third, the widespread government ownership of banks raises specific governance issues.

The debate in the corporate governance literature has mainly concentrated on whether corporate governance should focus exclusively on protecting the interests of shareholders, or whether such a focus should be broadened to protect the interests of other stakeholders (Macy and O’Hara 2003). A central issue in this debate is whether the directors of the organisation owe fiduciary duties of care and loyalty only to the shareholders of the organisation, or also to other stakeholders. What may be termed the “Anglo-American” or “neo-liberal” approach to corporate governance adopts the view that creation of value for shareholders should be given priority over the interests of other stakeholders. On the other hand, the “Continental European” approach (whether neostatist as in France, or neocorporatist as in Germany) to corporate governance calls for equal attention to be given to the interests of the other stakeholders in the organisation as well as to those of the shareholders.

Islamic banks are ethically funded organisations that primarily cater to the growing needs of Muslims who adhere to the Shari’ah rules and principles in investing their funds. These banks are currently the main type of financial institutions available for Muslims, because non-bank forms of intermediation in Islamic finance, unlike their conventional counterparts, are neither traditionally relied on nor well developed. A report by the International Organization for Securities Commissions (IOSCO) confirms the dominance of the Islamic banking sector within the Islamic financial services industry. It states, “As a result of its early head-start, Islamic banking is today the most developed component in the Islamic financial system and Islamic banks represent the bulk of Islamic financial institutions worldwide” (IOSCO 2004, 14–15). In contrast, Islamic insurance (takaful) is less developed although it is well established in some countries, notably Malaysia.

In place of interest-bearing deposits, Islamic banks mobilise funds through profit-sharing and loss-bearing investment accounts whose returns are, as a matter of Shari’ah jurisprudence (that is, that of the mudarabah contract, as explained below), based on the performance of the asset portfolios in which their funds are invested. Less commonly, a wakalah (agency) contract may be used in which the funds are managed by a wakeel (agent) in return for a fee which normally includes a fixed amount plus a performance-related element. The corporate governance issues raised are similar to the case of mudarabah, and in what follows references to such issues in the case of mudarabah should be understood as applying to wakalah. In the majority of Islamic banks, such investment accounts contribute the preponderant amount of the funds available to the bank for investment. However, investment account holders (IAHs) lack rights of governance such as shareholders enjoy, although like shareholders they are (legally speaking) a type of equity holder with residual claims to their share of the bank’s assets (Archer, Karim, and Al-Deehani 1998). While debt holders, with fixed contractual claims to the firm’s cash flows and assets, do not need a governance structure provided that these claims are met, residual claimants by definition have no such contractual rights and thus require a governance structure to protect their interests (Williamson 1996, Chapter 12); as Williamson points out, the law typically provides a governance structure for debt holders in case of default. In the case of IAHs, neither the Shari’ah nor secular law makes any such provision.

The absence of any governance structure in the case of IAHs is thus an anomaly and raises fundamental corporate governance issues—for example, possible conflicts of interest between the two classes of equity holders, disclosure of adequate information to enable IAHs to protect their interests, and so on. It also draws attention to market discipline, which was emphasised for the first time by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) in its capital adequacy framework (2004), known as Basel II, and raises the issue of the extent to which IAHs have the necessary mechanisms to exercise effective discipline on the management of the bank, given their lack of governance rights (see Archer and Karim 2006b). Furthermore, the mobilisation of funds through IAHs highlights the need to examine the approach adopted by central banks to regulate Islamic banks in order to help sustain the soundness and stability of the financial systems in the countries in which these banks operate (see Archer, Karim, and Sundararajan 2010, and Archer and Karim 2009, 2012).

This chapter attempts to enhance our understanding of the intricacies of corporate governance, market discipline, and regulation of Islamic banks. It argues that the existence of such profit-sharing and loss-bearing investment accounts with their equity-like, rather than liability-like, characteristics according to Shari’ah jurisprudence, together with a lack of clarity regarding the status of these investment accounts in practice, raise important questions of corporate governance, transparency, market discipline, and regulation for Islamic banks, which are examined below.

The remainder of the chapter is organised as follows. Section 2 discusses the salient characteristics of Islamic banks. Section 3 considers corporate governance issues of Islamic banks, and Section 4 examines the exercise of effective market discipline on the management of Islamic banks. The regulation of Islamic banks is addressed in the penultimate Section 5, and some concluding remarks are made in Section 6.

2. SALIENT CHARACTERISTICS OF ISLAMIC BANKS

Islamic banks (like any type of Islamic business organisation) are established so as to conduct their financial transactions in accordance with Islamic Shari’ah1 rules and principles, which prohibit, among other things, the receipt and payment of riba2 (interest). This means that Islamic banks cannot enter into interest-bearing borrowing or lending contracts, which is the basic business model of conventional banks.

As an alternative to the payment of interest, Islamic banks use two main types of accounts to mobilise funds, namely: (1) investment accounts, which are in most cases based on a version of the profit-sharing and loss-bearing mudarabah contract3 (or a wakalah contract) under which the funds are managed by the bank on behalf of their holders; and (2) current accounts. Investment accounts, unlike equity shares, are of limited duration and holders have the right to withdraw their funds subject to certain conditions (see below). Current accounts are sight deposits—that is, debt claims on the bank that can be withdrawn at any time—and are not entitled to any remuneration; they are “capital certain” since repayment is a contractual right protected by the bank having adequate equity capital. Islamic banks, therefore, perform a combination of two basic functions to mobilise funds, investment management and commercial banking, in addition to raising funds by issuing shares of common equity. As an alternative to lending funds and charging interest on them, Islamic banks use various Shari’ah-compliant financing contracts (for example, murabahah, musharakah, ijarah, salam, istisna’a, and so on)4 to invest funds available, which include funds under management for IAHs as well as the bank’s own (shareholders’) funds and those from current accounts. (See Exhibit 21.1 for a stylised balance sheet of an Islamic bank.) Funds under management for IAHs include both unrestricted and restricted IAH funds. The funds of the unrestricted IAHs are invested at the bank’s discretion, normally in the same asset pool as that in which the bank’s own funds and those from current accounts are placed. In contrast, the funds of the restricted IAH are invested in asset pools that are separately designated and distinct from the bank’s own funds (see Exhibit 21.1).

EXHIBIT 21.1 Stylised Balance Sheet of an Islamic Bank

| Assets | Liabilities |

| Cash and cash equivalents | Current accounts |

| Sales receivables | Other liabilities |

| Investment in securities | |

| Investment in leased assets | |

| Investment in real estate | Equity of investment accounts |

| Equity investment in joint ventures | Investment accounts |

| Equity investment in capital ventures | Profit equalisation reserve |

| Inventories | Investment risk reserve |

| Other assets | Owners’ equity |

| Fixed assets |

Islamic banks do not erect firewalls to separate, legally, financially, and managerially, their investment management and commercial banking services. Instead, as noted above and in contrast to the regulatory requirements in a number of European countries,5 the majority of Islamic banks commingle unrestricted IAH funds with their own funds, invest both under the bank’s management in the same investment portfolio, and report these investments and their results in the bank’s balance sheet and income statement. Hence, unrestricted IAH funds are far from being “ring fenced” from the bank’s own funds.

The relationship between IAHs as providers of funds and the bank in its capacity as fund manager is in most cases regulated by the mudarabah form of contract, which has detailed juristic rules derived from the Shari’ah.6 One of the absolute requirements for a valid mudarabah is the transfer of control over investment decisions, including all operating policies of the mudarabah, from the IAHs to the bank as mudarib. IAHs have no right to intervene in these investments and policies, which are the sole prerogative of the mudarib. A clear separation must occur between IAHs and their invested capital. However, unlike the situation with shareholders, this separation of capital ownership from management under mudarabah as currently applied does not provide any rights of governance or oversight to IAHs in exchange for their funds, as will be elaborated below. Moreover, the mudarabah-based structure does not provide the IAHs as investors with the kind of governance rights typically offered by mutual funds, such as a separate legal entity subject to requirements for annual reports, audit, etc. This situation sets the agency perspective of corporate governance of IAHs, which is unique to Islamic banks (see Archer and Karim 2009).

According to Udovitch (1970, 190):

This [arrangement] . . . in no way implies a transfer of ownership of the investment capital from the investor to the agent [mudarib]. While the agent’s control over the disposition of the investment is almost absolute, its ownership unequivocally remains with the investor [IAH].

This personal form of ownership of the capital and of the assets in which it is invested contrasts with the impersonal form of the entity, which is based on “the legal ‘separation’ of share ownership from ownership of the business assets” whereby “a company is legally the owner of its business assets, and the shareholding members have only the rights that are attached to their ownership of share capital” (Scott 1997, 3). The mudarabah concept of the personal form of ownership has implications for the accounting definition of an asset when Islamic banks report, as is currently the practice, on their balance sheets the assets financed by unrestricted IAHs.7 Furthermore, it is not clear how the underlying assets of sukuk (Islamic bonds), which use the mudarabah contract to mobilise funds, are to be characterised in terms of this concept of ownership—that is, what kind of ownership claim over the underlying assets is conferred by the sukuk.

One of the reasons for the separation of ownership from management in the mudarabah is that it is classified as a fiduciary contract, and the mudarib

. . . is considered a trustworthy and faithful party (amin) with respect to the capital entrusted to him, and therefore not liable for any loss occurring in the normal course of business activities; [however, the mudarib] . . . becomes liable for the property in his care as a result of any violation of this fidelity. (Udovitch 1970, 203–204)

To fulfil its fiduciary duty, the bank (as mudarib) is expected to generate the maximum profit for and to act in the best interests of IAHs (Saleh 1992). Indeed, the primary duty of the mudarib is to comply with the trust vested in it when managing the funds of IAHs. This means that the management of the Islamic bank owes a fiduciary duty to two categories of equity holders, shareholders and IAHs, whose interests may not necessarily be congruent. This in turn raises an important issue for the regulation of Islamic banks, namely the attention that needs to be given to their fiduciary duties as fund managers, as opposed to the current focus on their commercial banking aspects.

As a profit-sharing and loss-bearing financial instrument of limited duration, the mudarabah contract is neither a financial liability nor an equity instrument in the normal sense. According to Udovitch, it “combine[s] the advantages of a loan with those of a partnership; and while containing elements characteristic of both it cannot be strictly classified in either category” (1970, 171). In fact, mudarabah is sometimes described as a “partnership between work and capital,” where the provider of capital is the owner of the “partnership” assets. It should therefore be noted that an investment made under a mudarabah contract, as an equity investment, raises governance issues that do not apply to a loan.

However, unlike conventional equity instruments such as common shares, whose owners can have access to their capital only by selling them, IAHs are entitled to be repaid their capital, which is redeemable at maturity or at the initiative of their holders,8 but at net asset value, which in the event of losses will be less than the amount invested. This is because the mudarabah is a nonbinding contract and “as such either of the contracting parties involved therein may disengage himself at the moment of his choice either because he has lost his confidence in the other contracting party or because the latter has violated the trust, or even for no reason at all” (Saleh 1992, 139). However, the current practice in most Islamic banks is that IAHs (usually) have to secure the prior consent of the bank before they can withdraw their funds before maturity. Islamic banks can refuse to pay IAHs until the results of the investments financed by IAHs’ funds are determined,9 so that any losses can be taken into account. However, such a practice can expose the bank to reputational risk and impair its ability to attract potential IAHs. A number of Islamic banks maintain reserves against losses on IAH investments, a practice that mitigates the risk of paying out an amount in excess of its strict entitlement to an IAH who withdraws.

As noted above, IAHs lack the governance rights that company law accords to shareholders. They do not have: (1) the benefit of a board of directors to monitor management on their behalf, whose members they appoint and can dismiss; (2) the right to receive an annual report and to appoint external auditors to audit it; (3) the right to take part and vote in an annual general meeting or other general assembly; and (4) the right to participate in appointing the Shari’ah supervisory board10 of the bank. Contractually, IAHs may not “interfere in the management of their funds,” and violation of this condition can nullify the contract. This requirement not to “interfere in the management” is (questionably) interpreted as implying that IAHs have no right whatsoever to governance or oversight over the management of their investment. This means that the only possible means by which IAHs can express their dissatisfaction with the bank’s performance is to exercise their right to terminate their contractual relationship with the bank and “vote with their feet” by withdrawing their funds.

As already noted, according to Shari’ah jurisprudence Islamic banks do not guarantee the value of these investment accounts;11 nor do IAHs have the powers of creditors, who have a variety of control rights which they obtain when firms default or violate debt covenants, and which include the right in those circumstances to interfere in the major decisions of the firm.12 Their residual claim on the earnings or assets that relate to their funds after paying any creditors for debts that have been contracted specifically on behalf of the IAH, but not other creditors such as the current account holders, ranks similarly to the residual claim of the shareholders on the bank’s earnings or assets after paying any creditors other than those with claims on the assets of the IAH, for example current account holders (see Karim 2011).13 Moreover, while the mudarabah contract is neither a debt nor a conventional equity instrument, neither is it a type of conventional hybrid instrument comprising debt and equity characteristics. (For example, it is not debt with an embedded equity derivative.)

In the unrestricted type of mudarabah, IAHs authorise the bank to invest their funds at its discretion, including commingling the IAHs’ funds with those of shareholders. In the restricted mudarabah, in principle IAHs specify to the bank, among other conditions,14 the type of investment in which their funds should be invested—for example, real estate, currencies, leasing, and so on. In practice, Islamic banks offer a variety of “off-the-shelf” mudarabah investment funds, each with a specified (restricted) type of asset allocation, from which investors may choose. Hence, although holders of both types of investment accounts are exposed to different degrees of risk, their relationship with the management of the bank is subject to the same (very weak, not to say nonexistent) monitoring arrangements provided by the mudarabah contract, as currently practiced by Islamic banks.

The aggregate investment portfolio of an Islamic bank is usually financed by unrestricted IAH funds, plus shareholders’ equity and funds from other sources (for example, current accounts), the latter being mobilised on bases other than the mudarabah contract. If the aggregate investment portfolio yields a positive return, then the shares of profit are first allocated between the parties to the contract, IAHs, and the bank, according to their proportionate shares of their respective investments in the portfolio. The IAHs’ share of profit is then allocated between the IAHs and the bank (in its capacity as a mudarib) according to a predetermined percentage. The bank is also entitled to any profit earned from investing the funds provided by current accounts.

The bank’s share of profit relates to both its shareholders’ funds and to other funds invested in the investment portfolio that do not participate in profit sharing (for example, as noted above, current accounts which are capital-protected but nonparticipating).15 It is to be noted that shareholders’ funds invested in the investment portfolio (and elsewhere) and the other nonparticipating funds are not covered by the mudarabah contract, and are not governed by its rules. Hence, the bank’s shareholders receive the entire profit from these sources, and IAHs cannot claim any profit share from them. Typically, the mudarib share of profit allocated to the bank for managing IAH funds also constitutes a most important source of income to the bank’s shareholders.

If the bank’s aggregate investment portfolio yields a negative return, then, according to the mudarabah contract, this loss should be borne by IAHs and shareholders pro rata to their respective investments in this portfolio, bearing in mind what was said in the previous paragraph. Like that of shareholders, the liability of IAHs is limited to the amount of their investment and no more. In the case of a negative return, in addition to the shareholders’ proportion of the loss that is determined pro rata as indicated previously, the bank in its capacity as mudarib receives no profit-sharing fee on behalf of its shareholders (the mudarib share of profit having a lower bound of zero). However, according to the mudarabah contract, if the loss is due to misconduct or negligence of the mudarib, then the Islamic bank has to make good the loss.16 This exposes the bank to fiduciary risk (which does not appear to be a major consideration in the regulation and supervision of Islamic banks, although in a few countries the supervisory body places considerable emphasis on the banks’ duty to provide a return to IAH and to avoid exposing their funds to losses). In case of losses, the bank is likely to face reputational risk. As yet, however, in the absence of judicial findings it is far from clear what would constitute “misconduct or negligence,” and in particular how serious a lack of due diligence would have to be in order to be so classified. In general, this would be a matter for the secular courts to decide based on the applicable law of contract.17

3. CORPORATE GOVERNANCE ISSUES IN ISLAMIC BANKS

As already noted, the characteristics of Islamic banks imply that the management has a fiduciary duty to two categories of equity holders: shareholders and IAHs. The fiduciary duty that management owes to the shareholders in an Islamic bank does not differ from that in any other organisation. The fiduciary duty that the bank, represented by its management, owes to IAHs is governed (in most cases) by the mudarabah contract. However, judging by the position in other organisations,

The standard law and economics view regarding fiduciary duties is that corporations and their directors owe fiduciary duties to shareholders and to shareholders alone. (Macy and O’Hara 2003, 94)

This places the management of an Islamic bank in a difficult position of potential conflict of interests, which significantly complicates the corporate governance of these banks. Vogel and Hayes (1998, 133) also showed appreciation of this dilemma by wondering, “How can equity be ensured between the shareholders who are investors in the bank, on the one hand, and depositors who are investors in mudarabah funds managed by the bank, on the other?” Indeed, it is believed that:

The confusion of . . . trying to . . . require directors to balance the interests of various constituencies without according primacy to shareholder interests would be profoundly troubling . . . If directors are required to consider other interests as well, the decision-making process will become a balancing act or search for compromise. (ABA Committee on Corporate Laws 1990, 2253)

Although IAHs are equity holders and residual claimants, and the bank in its capacity as a mudarib owes them a fiduciary duty that should rank equally to that owed to the shareholders, IAHs appear to be the party whose rights might be compromised. This appears to be due not to the governance characteristics of the mudarabah contract as such, but rather to the context in which it is currently used in Islamic banking. If the mudarabah contract were used to mobilise funds in a collective investment scheme, the scheme manager would accord primacy to the interests of the holders of the mudarabah certificates, because they would be the owners of the fund. However, it is the use of the mudarabah contract to mobilise funds by Islamic banks in the context of a legal entity that has its own shareholders that appears to put the management of the bank in an ethical dilemma when it is faced with a conflict of interests between the two categories of equity holders. Since it is the shareholders who have the right to appoint, evaluate, and dismiss the management of the bank, this has the effect of relegating the status of IAHs (particularly unrestricted IAHs) to that of “second-class” equity holders. It is also an anomaly insofar as their status as residual claimants on the assets financed by their funds (just as the common shareholders are the residual claimants on the assets financed by other funds) should entitle them to the rights of governance, which, for good reason, normally attach to that status (Williamson 1996, Chapter 12). Thus, in the event of a conflict of interests between them and the common shareholders, the IAHs are clearly at an important disadvantage.

This raises the following fundamental question: Why do unrestricted IAHs place their funds with Islamic banks to manage these funds on their behalf as equity investors, while they do not get any governance rights in exchange for their funds and the risk they bear, but only the hope that they will receive a return on those funds? While, as Shleifer and Vishny (1997) point out, the same question may be asked in respect of equity investors (and especially minority shareholders) in other organisations, the situation in the case of unrestricted IAHs is worse. They are denied any governance mechanism that could serve to safeguard their interests and to mitigate potential conflicts of interests between them and the common shareholders (that is, between two categories of principals) on the one hand, and between them and the bank’s management as the agent both for them and for the common shareholders on the other hand.

One possible explanation is hypothesised by Archer, Karim, and Al-Deehani (1998) who pose the question: How may IAHs influence the behaviour of the bank’s management in order to safeguard their own interests within the terms of the mudarabah contract? Archer and colleagues (1998) suggest that IAHs may be able to safeguard their own interests by relying on shareholders’ monitoring to operate on their behalf, if it can be assumed that there is no significant conflict of interests between the two parties. They call this “vicarious monitoring.” In many cases, both shareholders and IAHs face the same portfolio investment risk insofar as the funds of both parties are commingled and invested in the same investment portfolio, this being so in many Islamic banks. Accordingly, it would seem that the IAH could expect a gross rate of return not less than the minimum that shareholders would expect to earn from investing their funds in a portfolio of projects of the same degree of risk.18 (Both IAHs and shareholders must meet certain expenses out of their gross returns; in the case of IAHs, the major expense is the mudarib share of profit to be paid to the bank.) On the other hand, if the aggregate investment portfolio yields a negative return, both parties lose part of their equity. In addition, shareholders receive no mudarib share from the bank’s managing the IAHs’ funds, although this can never be negative. (Assuming risk-neutrality of both parties, this asymmetry with respect to the mudarib share would not result in any conflict of interest. However, this may be a strong assumption. In particular, unrestricted IAHs, who typically view their accounts as a Shari’ah compliant alternative to conventional deposit accounts, are likely to be more risk-averse than shareholders.)

Moreover, even if the two sources of funds are neither commingled nor invested in the same investment portfolio, the characteristics of the mudarabah contract would arguably tend to produce goal congruence rather than conflict of interest between the two parties, notably because the IAHs can “vote with their feet” and withdraw their funds if dissatisfied with their return. Through the mudarib share of profit mechanism, shareholders stand to gain from any profit earned from investing IAH funds. The mudarib share of profit constitutes a valuable source of earnings to shareholders, particularly as it is a reward for the managerial effort of the bank that shareholders earn without (in principle) incurring any risk to their equity (see Al-Deehani, Karim, and Murinde (1999). This suggests that in order to maintain their return from this source of earnings, shareholders would have an interest in employing a management performance measure whereby the management of the bank would be expected to achieve a satisfactory rate of return on IAH funds—that is, a rate commensurate with the market rate of return earned by financial instruments having a similar level of risk. Achieving this would tend to motivate the existing IAHs to maintain their investments with the bank, as well as to attract other potential IAHs. On the other hand, if the aggregate investment portfolio yields a negative return, then shareholders would receive a mudarib profit share of zero. This would also tend to affect negatively the returns of shareholders in future periods, because existing IAHs would be tempted to shift to other investment opportunities and potential IAHs would be discouraged from investing in the bank.

However, the hypothesis of Archer, Karim, and Al-Deehani (1998) involves an assumption that shareholders have the ability to exercise the type of effective control of the bank’s management that would serve to safeguard IAH interests. According to Shleifer and Vishny (1997), there are a number of corporate governance mechanisms that suggest such an assumption is problematic. This would apply in situations where there are either diffuse shareholders or concentrated ownership.

In setups where there are diffuse shareholders, management is likely to have significant discretion over the control of corporate assets. Indeed, there are a variety of factors that keep diffuse shareholders from effectively exerting corporate control. For example, there are large informational asymmetries between management and diffuse shareholders. Also, diffuse shareholders frequently lack the expertise and incentives to close substantially the information gap and to monitor management. Indeed, a cursory review of the financial reports of Islamic banks reveals that diffuse shareholders as well as IAHs get a minimum amount of disclosure of information about the actual returns to IAHs and the extent to which the returns paid out are subjected to smoothing, the risk profile of the assets in which their funds are invested, and other relevant information that would help them in their decision making. In addition, managements of Islamic banks have significant discretion over the control of IAH assets, particularly in the case of unrestricted IAHs.

Furthermore, management may capture the board of directors because the board does not often represent the interests of diffuse shareholders. Indeed, “as ownership becomes more diffuse, managers can more easily manipulate information, form alliances with different groups, and capture control of the firm” (Caprio and Levine 2002, 5). This also has an effect on the extent to which the corporate governance problem can be solved by the use of incentive contracts. In the case of Islamic banks, it is uncertain whether the board of directors would represent the interests of IAHs. Rather, it is more likely that the board would cater for the interests of the shareholders, who normally have representatives on the board. For example, Bahrain Islamic Bank disclosed in its 2003 annual report that it will no longer allow its IAHs to share in the returns generated from investing funds available from current accounts, as was the case in the past, because this is the exclusive right of the shareholders who bear the risk while the IAHs do not. (A share of such returns may have been paid to IAHs in the past when management felt that otherwise their level of return would be uncompetitive.)19

Islamic banks tend to be opaque about the bases on which management incentive contracts are established: is it on the total investment income earned by the bank before the allocation to IAHs of their share in that income, or is it the investment income (including the mudarib share) earned for the shareholders? If it is the latter, which is most likely the case, then management would have an incentive to manipulate that amount in order to maximise it (and, hence, their incentive pay), which would also coincide with the interests of the shareholders.

On the other hand, if ownership is not diffuse, while large investors have the incentive to collect information, to monitor management, and to exert control over managerial decisions, these activities have their cost, too, and are not without their drawbacks. As Shleifer and Vishny (1997) point out, large investors act in accordance with their own interests, which may be at the expense of other investors and stakeholders. This could also have unfavourable consequences on the firm’s resource allocation. In addition, large investors are likely to get preferential treatment at the expense of other investors and stakeholders. They may influence dividend policy or cause the firm to engage in related party transactions, in ways that benefit them to the detriment of the firm’s other shareholders (Dann and DeAngelo 1985) and IAHs.

Such actions are also mirrored in the behaviour of some Islamic banks. For example, we have observed instances of the following. There are Islamic banks that have attempted to pay shareholders a constant high rate of dividends for a long period, while IAHs in those banks were receiving minimum returns. This apparently was due to manipulation of the formula by which profits were allocated between IAHs and the shareholders, and of the manner in which certain expenses were charged to IAHs. In addition, in certain Islamic banks, management tend to please the board of directors, which is controlled by a few large shareholders, by “cherry picking” the more attractive projects (in terms of risk and return) for investment mainly from shareholders’ funds, while IAH funds are used to finance inferior projects.20 This type of behaviour by management appears to be influenced by the timing of the renewal of management’s contract—a matter in which common shareholders, but not IAHs, have a say. These factors can have as a consequence a rate of return on unrestricted IAHs funds that is only about 10 percent of the rate of return on shareholders’ funds.

Another issue concerned with shareholders (through management) being benefited at the expense of IAHs relates to what are known as the profit equalisation reserve (PER)21 and the investment risk reserve (IRR),22 the purpose of which is to smooth IAH income and cover IAH losses, respectively. In the contract that regulates their relationship with the bank, IAHs agree in advance on the proportion of their income that may be allocated to both reserves, which (subject to this) is determined by the management of the bank at their own discretion. In the same contract, IAHs also agree to give up any right they have to these reserves when they terminate their contractual relationship with the bank. It should be noted that before Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions promulgated its Financial Accounting Standard No. 11, Provisions and Reserves (1999b), no Islamic bank had disclosed information in its annual report on the smoothing of IAH profits (or covering of losses) or by how much.

Prior to the development of the concept of the PER, Islamic banks used to enhance the returns of IAHs to match the competitive returns in the market by donating the amount needed to smooth the returns of IAHs from the bank’s mudarib share. The low rate of return on IAH funds could be due to the investment of these funds in assets with a relatively long maturity (for example, murabahah or bay’ bithaman ajil) with a fixed rate of return that falls short of the rate currently available in the market on comparable instruments,23 a circumstance analogous to an adverse interest rate mismatch in a conventional bank.

The shareholders’ decision to agree (which is a Shari’ah condition) to give up part or all of their profits to enhance IAH returns means that the shareholders accept that the risk attaching to the returns of a portfolio of assets financed partly or wholly by IAH funds is “displaced” so that it is borne largely by themselves (the shareholders).24 (In the case of conventional deposits, the risk of the assets in which the depositors’ funds are invested is, of course, totally borne by the shareholders.) Failure to smooth the IAH returns might result in a volume of withdrawals of funds by IAHs large enough to jeopardise the bank’s commercial position. On the other hand, smoothing the IAH returns is unlikely to attract adverse attention by the banking supervisor, because it would reduce the danger of the bank being a source of systemic risk through a run by IAHs (see Archer and Karim 2012). Indeed, in some countries (for example, Qatar and Malaysia) the banking supervisor takes the view that Islamic banks should not allow unrestricted IAHs to suffer a loss of their capital or a major fall in their returns. In this sense, the displacement of risk on to the shareholders might be thought of as being, in part, a type of “political cost” that shareholders incur in order to avoid falling foul of the industry regulator. While this practice may occur in relation to the funds of restricted as well as unrestricted IAHs, it is particularly problematic in the case of the latter whose funds are commingled with those of the bank’s own (common shareholders’) funds.25

Such a practice might be considered to support the “vicarious monitoring” hypothesis suggested by Archer, Karim, and Al-Deehani (1998), in the sense that shareholders are willing to sacrifice part or all of their mudarib share in the short term in order to compensate IAHs for an inadequate level of return on the assets in which their funds are invested. This would have the effect of encouraging the IAHs to continue investing their funds with the bank because (as pointed out by Al-Deehani, Karim, and Murinde 1999) such continuity is very much in the interest of the shareholders, particularly if unrestricted IAH funds represent 60 percent or more of the funding side of the bank’s balance sheet, which is the case with many Islamic banks.

It was to mitigate the effects of this practice, which could not be sustained in the longer term if the shareholders had consistently to forgo the bank’s mudarib share, that the management of many Islamic banks introduced the profit equalisation reserve (PER). While the declared objective of the PER was to reduce the volatility of IAH returns, it provided management with a mechanism to tap this pool of funds to relieve shareholders of the burden of smoothing the returns of IAHs or to mitigate problems of asset–liability management. In fact, as with earnings management techniques in general, a major objective is to reduce transparency and management accountability,26 in this case to the detriment of IAHs, since while the amount by which the returns of IAHs are smoothed from the PER creates value for shareholders, it does not do so for IAHs (Archer and Karim, 2004). In fact, it represents a cost (in terms of foregone returns while the reserve is being built up), which IAHs incur if they invest their funds under a form of mudarabah contract that permits management to retain a proportion of the profit share in order to build up a PER that would otherwise have been paid out to them.

Similar considerations apply to the investment risk reserve (IRR). In addition, the IRR may give rise to moral hazard problems similar to those arising from deposit insurance schemes, since the existence of IRR in Islamic banks is likely to encourage management to engage in excessive risk taking. This is because losses can be covered, at least in part, by this reserve, which is financed only from the funds of IAHs and not those of shareholders, and this is likely to increase the management’s risk appetite to a higher level than that of the IAH. This is especially the case since the IRR is appropriated from profits after the calculation of the mudarib share, which is unaffected, while in the case of a loss the mudarib share is zero, irrespective of the size of the loss. Even if a loss absorbed by the IRR were due to misconduct and negligence, in which case according to the mudarabah contract it should be borne by the shareholders, it would be difficult for IAHs to be aware of this because of the absence of either adequate disclosure or other means to detect such a loss. In addition, as noted above, it is unknown to what extent the legal system in the countries in which Islamic banks operate would support the right of IAHs to be compensated for such losses in such cases. The criteria for proving negligence may be hard to satisfy, and the same may be said of misconduct if there is no clear breach of contract.

Hence, while the lack of any governance structure in the mudarabah contract may leave IAHs dependent on shareholders to monitor the performance of the management of the bank, the existence of PER and IRR is likely (and is arguably intended) to conceal from IAHs lapses in that performance, and more generally the need for them to seek other corporate governance mechanisms (see Archer and Karim 2006). In fact, smoothing the returns and absorbing losses through these reserves have the effect of making the returns on IAHs behave more like those on conventional deposits—that is, a debt instrument. This effect will likely continue as long as there are adequate balances in both reserves to reduce the volatility of the returns of these account holders and to act as a buffer to absorb losses before they are seen to erode the equity of IAHs. Such a situation is furthermore sustained by, and also contributes to, both weak market discipline, which tends to exist in almost all countries in which Islamic banks operate, and a lack of transparency (which is a common feature of banks in general, and of Islamic banks in particular).

More generally, the fact that unrestricted IAHs tend to be risk-averse savers while shareholders will typically have a greater risk appetite, implies the likely existence of incentive misalignment between IAHs and shareholders, which casts doubt on the existence or effectiveness of “vicarious monitoring.”

Another implication of the PER (and of the lack of transparency) is that it would distort competition among Islamic banks, in the sense that IAHs would not see the need to withdraw their funds, which is the only means available for them to discipline Islamic banks, as long as IAHs receive a (smoothed) rate of return on their investment that is commensurate with the going market rate (see Archer and Karim 2006b). Furthermore, the existence of the IRR would reduce the ability, if not the incentives, of IAHs and shareholders to monitor the bank’s performance, and thus would negatively affect market discipline. This is similar to one effect of deposit insurance schemes, which is to reduce the incentives of depositors to monitor banks, while subordinated debt holders, to the extent that they believe the existence of central banks as lenders of last resort might protect them, also have their incentive to monitor the bank curtailed (Caprio and Levine 2002).

The theme emerging from the foregoing analysis of corporate governance of Islamic banks suggests that, although the management owe IAHs a fiduciary duty similar to that of shareholders, the rights of the former are likely to be compromised because of their weak governance rights and structure compared to the shareholders, even though both are equity holders and residual claimants on the assets held or managed by the bank. Furthermore, although IAHs may depend to some extent on shareholders to safeguard their interests, the above analysis suggests that such reliance has significant limitations so that, far from serving the interests of IAHs, and particularly those of unrestricted IAHs, current practice in profit smoothing and the use of reserves for that purpose involve a lack of transparency that aggravates their exposure to conflicts of interests and inhibits the development of market discipline.

Indeed, the current status of unrestricted IAHs appears fundamentally anomalous from a corporate governance perspective. Not merely is “vicarious monitoring” unlikely to be very effective, for the reasons just explained, but in the circumstances in which it is most likely to be effective—that is, full commingling of shareholders’ and IAH funds—there is also the greatest likelihood of conflicts of interests regarding risk appetite. However, such limitations seem not to have affected the magnitude of IAH funds in Islamic banks, in some of which they represent a high percentage compared to other sources of funding (see Exhibit 21.2, and also Exhibit 2 in Al-Deehani, Karim, and Murinde 1999).

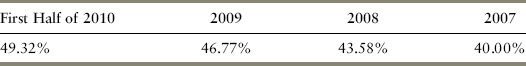

EXHIBIT 21.2 The Average Percentage of Unrestricted PSIA (out of total assets) for 44 Banks for Years 2007–2009 and the First Half Year 2010

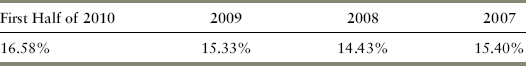

For restricted profit-sharing investment accounts (PSIA), data for only seven banks was available consistently for these years. Therefore, based on the data submitted by the IIFS, the following are the average percentages of restricted PSIA (out of total assets) for these years (see Exhibit 21.3).

EXHIBIT 21.3 The Average Percentages of Restricted PSIA (out of total assets) for 2007–2009 and the First Half Year 2010

In effect, unrestricted IAHs seem to behave very much like depositors in conventional banking, rather than like a category of equity investors: They are passive and risk averse, being content with very modest rates of return compared to those available to shareholders. But they do not have the status of creditors and the attendant governance rights in case of default. In fact, it is not even clear what would constitute default in regard to the Islamic bank’s obligations to them; this would seem to be restricted to cases of misconduct or negligence, as mentioned in Section 2 earlier.

With this background, the next section examines the extent to which IAHs could impose effective market discipline on Islamic banks, and insofar as the abilities of IAHs to achieve this objective are limited, Section 5 discusses the approach to the regulation of Islamic banking that may be relevant in light of the initiative taken by a number of central banks and monetary agencies to develop prudential and supervisory standards that cater for the specificities of Islamic banks.

4. EXERCISING EFFECTIVE MARKET DISCIPLINE ON ISLAMIC BANKS

The 2004 BCBS’s Revised Framework (Basel II) took the view that market discipline is increasingly important in a world where banking activities were becoming more and more complex. This is also included in the recently issued BCBS post-crisis Framework, known as Basel III. Thus, both Pillar 3 of Basel II and Basel III encourage greater bank disclosure to strengthen market discipline.

According to Belkhir (2012), “The recent financial crisis has, however, battered the belief in the effectiveness of markets to discipline bank risk, as many voices pointed to the failure of market mechanisms in preventing banks from taking excessive risks.” Furthermore, “while the lack of market discipline has been pointed out as one of the main reasons for the excessive risks taken by banks in the pre-crisis years, others argue that market participants cannot be effective in curbing banks’ excessive risk-taking in the presence of implicit guarantees, such as the too-big-to-fail guarantee” (Belkhir 2012).

According to Crockett (2001, 3), for market discipline to be effective four prerequisites have to be met: “First, market participants need to have sufficient information to reach informed judgments. Second, they need to have the ability to process it correctly. Three, they need to have the right incentives. Finally, they need to have the right mechanisms to exercise discipline.” In what follows, an attempt will be made to examine the extent to which IAHs qualify for Crockett’s prerequisites for imposing effective market discipline on Islamic banks.

The hypothesis suggested in Archer, Karim, and Al-Deehani (1998) assumes that one of the factors that would give IAHs comfort is that these investors are aware, among other things, of the commingling of their funds with those of shareholders and of the proportions in which the portfolio of assets is financed by IAHs and shareholders, respectively, and how the banks calculate the allocation of profit sharing between the two parties. However, as noted by Archer and colleagues (1998), these assumptions are problematic given the lack of adequate disclosure by Islamic banks which results in major information asymmetry between IAHs and the bank’s management, as described next.

Prior to the establishment of AAOIFI, the lack of adequate disclosure by Islamic banks was very apparent. This may have been due to a lack of appreciation of the financial reporting requirements with which Islamic banks should comply in order to provide adequate disclosure to IAHs in their capacity as equity investors, not depositors. Indeed, a cursory review of the annual reports of Islamic banks prior to the implementation of AAOIFI’s standards reveals that Islamic banks were hardly required to disclose any information relating to the investment of IAH’s funds—for example, (i) the type of assets in which the funds of these account holders are invested, (ii) the risks to which they are exposed and how the bank manages those risks, (iii) the bases of allocation of profits between the bank and IAHs, including the type and amount of expenses that the bank charges to their accounts, (iv) whether either of the two types of investors (IAHs or shareholders) is given priority in placing liquid funds available for investment, and (v) whether the returns of IAHs are smoothed and if so by how much, and so on.

Islamic banks were also divided as regards the accounting treatment of IAHs on their balance sheet. Some banks reported unrestricted IAH funds on the balance sheet under liabilities,27 while others treated them as part of equity. Yet a third group of banks treated all IAH funds as off-balance sheet items. Karim (2001) argues that these differences were due to the approaches adopted by various countries to regulate Islamic banking.

Such a lack of transparency meant that there was considerable information asymmetry between IAHs and the management of the bank, which prevented the former from being adequately informed about the performance of their investments and at the same time provided the management with enough freedom to favour shareholders (to whom they are accountable via the board of directors and the annual general meeting) at the expense of IAHs (particularly unrestricted IAHs), who have no such governance rights. On the other hand, with the exception of the accounting and governance standards issued by AAOIFI to enhance the transparency of matters relating to IAHs, very few regulations were promulgated by authorities in the countries that host Islamic banks to address the corporate governance issues raised by the existence of this type of equity investor. In addition, while anecdotal evidence suggests that the standards prepared by AAOIFI have created much awareness of corporate governance issues relating to IAH, their impact has been greatly restricted by the fact that only a limited number of countries have adopted these standards, and that even in those countries compliance with them is patchy (see Mustafa 2003).

However, to improve corporate governance for IAHs through disclosure requires a cross-sectoral approach to the regulation of the institutions that accept these investment accounts (Karim 2011; Archer and Karim 2012). Such an approach draws, inter alia, upon securities regulation, which requires that adequate attention should be given to investor protection (which does not mean a guarantee of capital, but providing investors and prospective investors with full disclosure of information both before and after they make any investment, whereby they are better able to assess the potential risks and rewards of their investments and, thus, to protect their own interests).

As will be discussed later, almost all supervisors have approached the regulation of investment account holders from the perspective of depositor protection rather than investor protection28 (see also Archer and Karim 2004; 2012; Karim 2011), and this appears to have placed the regulation of these accounts solely in the hands of the banking regulators, with hardly any involvement by the securities regulators who tend to be unaware of either the complexities or the disclosure requirements of IAHs in Islamic banks.

On Crockett’s second prerequisite—namely, the need to have the ability to process the information correctly—suffice it to say that the complexities of the operations of Islamic banks are hardly understood even by many in the industry. Indeed, not many would be familiar with the inherent risks of the contracts used by Islamic banks in both the utilisation and mobilisation of funds. For example, until AAOIFI published its accounting standard on leasing, almost all Islamic banks—with the approval of their external auditors—invariably used to treat ijarah muntahia bittamleek (IMB)29 as a finance lease, although according to the Shari’ah provisions of the contract the lessor is not allowed to transfer substantially all the risks and rewards of ownership to the lessee. From the perspective of the Basel II and Basel III requirements, the treatment of IMB by Islamic banks prior to AAOIFI’s standard would mean that the banks entering into such a contract as lessor would be exposed only to credit risk. However, according to both the Shari’ah precepts of the contract and its substance, the bank as lessor under IMB would be exposed to a significantly higher level of operational risk than a lessor under a conventional finance lease (as well as being similarly exposed to price risk on the value of the asset as quasi-collateral, subject to “haircuts”), and hence should be expected to provide regulatory capital to cater for these risks, an issue that is challenging for supervisors of Islamic banks (see also Archer, Karim, and Sundararajan 2010).

Another example relates to the salam contract, which exposes the Islamic bank to both credit risk and commodity price risk as the bank agrees to buy the commodity on a future date against current payment and also holds the commodity in question until the bank can convert it into cash, unless it has entered into a parallel salam contract. The latter contract enables the bank to hedge against price risk, but only partially because the Shari’ah provisions of the contract prohibit making the execution of the parallel salam contract dependent on the execution of the original salam contract. In this case, AAOIFI’s Standard No. 7 on salam and parallel salam specifies that the underlying asset of the contract should be measured at lower of cost and market price when it is received by the bank. However, if the customer defaults on its obligation to deliver the commodity to the bank, the latter has nevertheless to fulfil its obligation in the parallel salam by acquiring the commodity from the market, which exposes the bank to price risk (in addition to the inherent credit risk) in the event of such default.30 On the other hand, if the bank does not enter into a parallel salam, it is fully exposed to price risk on its “long position” in the asset, which it would sell after its delivery on the maturity of the contract.

The lack of appreciation of, among other things, the intricacies of both risk management and financial reporting relating to the operations of Islamic banks by IAHs and other consumers of the Islamic banks’ services, together with the lack of adequate disclosure, indicate that neither of Crockett’s first or second prerequisites is satisfied in order for market discipline to be effective in the case of these banks.

Crockett’s third and fourth prerequisites regarding the right incentives and mechanisms can best be addressed by looking at the similarities and differences between subordinated debt and IAH funds (see Archer and Karim 2006b). There have been proposals (for example, Evanoff and Wall 2000; Hamalainen 2004) to ask banks to incorporate subordinated debt into their capital as an additional financial cushion, as this is “one of the most effective market mechanisms for relaying information about a bank’s risk profile . . . [This is because] subordinated debt holders . . . do not profit from a bank’s risky investments if those investments turn out to be profitable, but they stand to lose their money if those investments are not profitable. For that reason, holders of subordinated debt would have a very strong incentive to monitor closely the activities of banks” (Rodriguez 2002, 18). Indeed, subordinated debt (subject to certain conditions regarding maturity and risk absorption) may be accepted as part of banks’ regulatory capital under Basel III.

IAH funds share several features of subordinated debt, including, most importantly, the subordination of their claims to those of creditors relating to debt contracted specifically on behalf of IAH by the bank. Also, unlike conventional depositors, neither holders of subordinated debt nor IAHs are in a position to initiate a conventional bank run, and stand to lose part or all of their capital if their investments yield negative returns. This provides holders of both instruments with incentives to monitor the bank’s choice of risk, especially as both instruments may be used as a means of leveraging the shareholders’ returns (in the case of IAHs, because of the mudarib share of profits—see Al-Deehani, Karim, and Murinde 1999). IAHs are entitled to profits that are related to the investment of their funds, which may or may not be commingled with the bank’s own (shareholders’) funds. If IAH funds are commingled with shareholders’ funds in the same pool of assets, they are likely to constitute the larger share of the investment in the asset pool, but the choice of asset allocation may reflect management’s view of shareholder preferences in terms of risk–return characteristics. Hence, there is always an incentive for the management of both conventional and Islamic banks to increase risk through leverage using subordinated debt or IAH funds, respectively, because the shareholders in both types of banks will benefit fully when the banking business is successful. Shareholders may benefit more from the “upside” of risk to which there is no firm upper bound, but may not be exposed proportionately to the “downside,” which is limited to the loss of their own (but not IAHs’) capital.31 In certain circumstances, such as incipient financial distress, this may provide management with a motive for taking excessive risks (that is, “betting the firm”).

In case of a bank failure, the losses of the shareholders in both types of banks are limited to their share in the bank’s capital, and holders of subordinated debt in conventional banks have a claim on the assets of the banks that ranks after those of other creditors but before that of shareholders. Unrestricted IAHs, on the other hand, rank after all creditors that have been contracted specifically on their behalf, and in the case of commingled funds they have the residual claim on the proportion of the asset pool that was financed by their funds.

However, in contrast to holders of subordinated debt, IAHs lack a mechanism whereby they contribute significantly to effective market discipline—namely, a quoted market price that reflects the market’s view of the bank’s financial position. Subordinated debt bonds are tradable in the financial markets, and their yields provide the market’s assessment of the risks taken by the banks. “This implies that the supervisor will get an early warning signal, either through a higher required risk premium by the investors or though trouble when issuing new bonds. So the holder of the bond will have the incentive to monitor the bank continuously, strengthening the market discipline” (Sijben 2002, 61). These mechanisms, however, are not available to IAHs because their investments are not tradable in the capital markets. Hence, IAHs lack this means of signalling to the market their assessment of the risks taken by the Islamic bank and thus putting pressure on the bank’s management via the capital market as indicated above.

Furthermore, while IAHs, like any investors, are expected to monitor the bank’s choice of risk because their capital is exposed to losses, the lack of adequate disclosure of relevant information makes this a difficult task for IAHs, thereby further reducing their ability to exercise effective market discipline. This may encourage Islamic banks to increase their risk to a level in excess of the risk appetite of IAHs, especially since the latter are not in a position to require a higher risk premium on their investment; their only recourse is to withdraw their funds, subject to a loss of accrued profit share if they do not observe the waiting period set out in their mudarabah contract.

In addition to the availability of adequate information to gauge the riskiness of the bank by depositors, Blum (2002) and Cordella and Yeyati (1998) argue that a conventional bank’s risk choice will be efficient if the bank deposits are uninsured. This is so because banks take account of the impact of their risk choice on depositors, since they will demand higher compensation should the bank incur higher risk. However, if deposits are insured or the bank’s risk choice is not observable by depositors, the bank will increase risk at the expense of depositors (Baumann and Nier 2003).

Although contractually IAHs are uninsured because they bear their own risk of loss, the use of an IRR by Islamic banks may have “safety net” effects for IAHs that reduce their incentives to monitor management.32 Furthermore, in a number of countries, including some that have a high density of Islamic banks (for example, Bahrain and Sudan), Islamic banks enjoy the benefits of a formal system of Shari’ah-compliant (that is, takaful-based) deposit insurance. The introduction of deposit insurance is, however, contrary to what is recommended in a report by the World Bank (2001) which calls for developing countries that do not have a formal system of deposit insurance to refrain from establishing one, especially if the institutional environment in that country is weak. In addition to these safety nets, the availability of PER tends to reduce the incentives of IAHs to exercise market discipline because, as argued earlier, they would not see the need to withdraw their funds as long as they received a smoothed rate of return on their investments that is commensurate with the market rate (Archer and Karim 2006b). However, while these measures may potentially curb the incentives of IAHs to monitor the bank’s risk choices, they also tend to provide Islamic banks’ management with the opportunity to take excessive risk.

From the analysis in this section, it can be appreciated that given their lack of a governance structure, unrestricted IAHs hardly meet Crockett’s four prerequisites, which would enable them to impose effective market discipline on Islamic banks. This highlights the emphasis that should be placed on regulating Islamic banks, which is examined in the next section, in order to enhance, among other things, the corporate governance in these banks with a view to protecting the interests of IAHs.

5. REGULATION OF ISLAMIC BANKS

In almost all cases, Islamic banks are regulated by the central banks in the countries in which they operate. However, there is an absence of commonly accepted regulatory and supervisory guidelines and best practices that cater for the specificities of Islamic banks—for example, the treatment of IAHs in calculating the bank’s capital adequacy ratio (see, for example, AAOIFI 1999c; Archer, Karim, and Sundararajan 2010; Karim 1996), the risk weightings of the Shari’ah contracts that the banks use to utilise their funds, and so on. Accordingly, central banks have tended to supervise and regulate Islamic banks using the same guidelines as those developed for conventional commercial banks, albeit with some amendments introduced by individual central banks.33 However, in doing so, central banks appear to have adopted an approach that emphasises depositor protection rather than a cross-sectoral approach that combines both depositor and investor protection to cater for the commercial banking and investment management services which Islamic banks perform (Archer and Karim, 2012).

Contractually, since IAHs bear their own risk of loss, it would not be expected of central banks to protect the equity of these investors by the same methods that they use for depositors such as current account holders, who lend their money to the bank and have a contractual right to redeem their funds in full as and when they demand to do so (or, indeed, holders of conventional “capital certain” deposit accounts). Hence, like investors in collective investment schemes (CIS), IAHs should logically be regulated using the approach of securities regulators, which is more concerned with investor protection and places more emphasis on fiduciary responsibility or establishes detailed regulations designed to monitor potential conflicts of interest facing the managers of a CIS, and perhaps especially the management of an Islamic bank, which may look after the interests of shareholders at the expense of IAHs. In addition, securities regulation would require disclosure of relevant information about the Islamic bank’s investment objectives and policies, and operational guidelines that govern the relationship between the bank and IAHs. This would allow IAHs to be in a better position to assess the potential risks and rewards of their investments and, accordingly, to protect their own interests.

However, such an approach to regulation would place the central banks concerned in a dilemma. On the one hand, adopting a securities regulation approach would give a faithful representation of the contractual relationship between IAHs and the bank, and at the same time give IAHs an incentive to exercise effective market discipline with respect to the bank’s management. On the other hand, insofar as IAHs have deposited their funds in a bank rather than investing them in a separate CIS, there would be a possible exposure to systemic risk in the banking system.

More specifically, if IAHs were paid no returns on their investment accounts or low returns compared to the market return on similar instruments as well as bearing the risk of loss, they would be inclined to withdraw their funds, leading to a liquidity crisis for the bank that could have effects similar to those of a conventional bank run. Such a scenario would be of great concern to central banks, because not only might this situation threaten the individual bank’s solvency, but it could also trigger systemic risk (which is considerably less evident or nonexistent for the nonbanking financial sector—see, for example, Llewellyn 1999; Dale 1996) in the whole banking sector, thereby threatening the soundness and stability of the financial system in the country.

The risk to an Islamic bank of not earning a rate of return on the assets it manages on behalf of its IAHs that is sufficient to meet their expectations based on current market conditions is an analogue of “interest risk in the banking book” in conventional banks, and is known as “rate of return risk” (see, for example, IFSB 2005). In order to mitigate this rate of return risk, the banking supervisors have allowed or even encouraged Islamic banks to use the PER and IRR, which, as argued earlier, have the effect of weakening market discipline. Moreover, in some countries the banking supervisor has encouraged or even required Islamic banks to treat unrestricted investment accounts as (in substance) capital certain. Such a supervisory requirement results in the investment accounts having de facto capital certainty, even though being based on the mudarabah (or in some cases the wakalah) contract they do not possess de jure capital certainty.

It is worth noting that, as with many of their conventional commercial counterparts, the portfolios of assets of the majority of Islamic banks are nonmarketable and are typically held on the balance sheet until maturity.34 Hence, unlike the majority of CISs, many Islamic banks would not be able to liquidate the majority of their assets in a short time, without incurring substantial (and possibly catastrophic) losses.

6. CONCLUDING REMARKS

This chapter has argued that the profit-sharing and loss-bearing features of IAHs raise specific problems of regulation with respect to Islamic banks. To a considerable extent, profit-sharing investment accounts resemble CISs, yet, particularly in the case of unrestricted IAHs, their funds are managed within a banking structure by virtue of a mudarabah contract which places no “firewalls” between the investment funds and the bank. Unrestricted IAHs are thus a form of limited-term equity investors in an Islamic bank, but have no governance rights other than that of withdrawing their funds (which has the disadvantage of entailing the forfeiting of accrued profit share). Moreover, to minimise the likelihood of their doing this, Islamic banks employ various profit-smoothing techniques, which (like earnings management in general) have the effect of frustrating market discipline.

However, insofar as both Islamic banks and their supervisory authorities in some countries consider unrestricted investment accounts to be a product designed to compete with, and to be an acceptable substitute for, conventional deposits, profit smoothing in such an environment may be considered to be an inherent attribute of the product rather than a means of deliberately avoiding transparency and market discipline, especially if it is combined with in-substance (de facto) capital certainly. Indeed, as noted above, in some such countries unrestricted IAHs may benefit from deposit guarantee schemes. Nevertheless, the compliance of some of such practices with Shari’ah rules and principles seems open to doubt, to say the least. Moreover, the desire to offer as good a substitute as possible for conventional deposits does not justify obfuscation or a lack of transparency in financial reporting.

The implications of this analysis for financial services regulators are therefore twofold. In the first place, more emphasis needs to be placed on the need for transparency. Considerable improvements in transparency could be achieved by the effective enforcement of AAOIFI’s financial reporting standards, which need to be updated on a timely basis as both industry practices and the IASB’s international financial reporting standards evolve, and of the IFSB’s Guidance on Disclosures to Promote Transparency and Market Discipline (IFSB 2009). Second, IAHs need to be considered as investors in need of regulatory protection as such—that is, investor protection. Alternatively, if unrestricted IAHs are considered to be virtual depositors, the implications of this in terms of capital adequacy need to be enforced by the supervisory authority (see Archer, Karim, and Murinde 2010)—namely, the treatment of unrestricted IAHs in the same way as liabilities for the purpose of calculating the capital adequacy ratio.

What is clearly unacceptable is that investment accounts, which are juristically profit sharing and loss bearing, should be left with an ambiguous status that allows Islamic banks to finesse transparency, capital adequacy, and investor protection requirements in respect of such financial instruments by treating them as virtual deposits for marketing purposes but as equity instruments (or even off-balance sheet) for the purpose of capital adequacy, while financial services regulators do not consider them as calling for measures of investor protection.

NOTES

1. Shari’ah is the sacred law of Islam. It is derived from the Qur’an (the Muslim holy book), the Sunna (the sayings and deeds of Prophet Mohammed), ijma’ (consensus), qiyas (reasoning by analogy), and maslahah (consideration of the public good or common need).

2. Riba is translated strictly as usury, but interpreted by modern Islamic scholars as being equivalent to interest (see Mallat 1988; Saleh 1992; Taylor and Evans 1987).

3. The original form of the mudarabab contract is very similar to that of the commenda contract in general use by Italian and other merchants in the late Middle Ages and early modern period (see Bryer 1993; çizakça 1996).

4. Murababab is sale at cost plus an agreed-upon margin of profit; musbarakab is a form of partnership; ijarah is leasing; and salam is a purchase of a commodity for deferred delivery in exchange for immediate payment. For more details on these and other contracts, see Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI) (2002a).

5. Franks, Mayer, and Correia da Silva (2003) report that in the seven European countries that they surveyed, the regulatory authorities require asset management firms to separate their assets from those of their clients.

6. For a comprehensive coverage of these details see, for example, Udovitch (1970) and Vogel and Hayes (1998).

7. It is worth noting that in order for an asset to be reflected on the balance sheet of an Islamic bank, AAOIFI (1993, para. 22) requires, among other things, that “the Islamic bank should have acquired the right to hold, use or dispose of the asset.”

8. In this respect, they are a type of “puttable instrument” as described, for example, in International Accounting Standard No. 32. However, the “put option” (i.e., the right to withdraw the NAV) may be not absolute, but subject to the bank’s agreement to its exercise.

9. This is similar to the practice by many mutual funds firms, which prohibit or discourage market timers (investors who rapidly trade in and out of mutual funds) because it is claimed that this hurts buy-and-hold shareholders, as the fund manager has to keep extra cash ready to pay the exiting market timer, which dampens performance. Islamic banks reward IAHs who invest their funds with the bank for a longer period by allocating them a higher profit ratio compared to the profit ratio allocated to IAHs who opt to have access to their funds on demand or invest them for a short period, because the bank, like fund managers, has to make cash available to meet withdrawals by these IAHs.

10. This is a part-time board comprising (usually) three Shari’ah scholars appointed (in many cases) voluntarily by almost every Islamic bank to assure its clients (mainly those who are keen to have their funds managed in accordance with Shari’ah rules and principles) that its transactions are in compliance with Shari’ah precepts. For more information on this board, see AAOIFI (1999a).

11. According to Saleh (1992, 134), “The reason for the unacceptability of the agent’s [mudarib] guarantee is that such an agent, likewise any partner, is considered a trustworthy party (amin) with respect to the capital remitted to him. He is therefore not liable for any loss occurring in the normal course of business activities, except when there is a breach of trust.” However, although “the capital provider is permitted to obtain guarantees from the mudarib [to which the former can have recourse] . . . in cases of misconduct, negligence or breach of contract on the part of the mudarib” (AAOIFI 2002b), this seems not to be practiced by Islamic banks in their current dealings with IAHs.

12. The Shari’ah provides that, in case of proven misconduct or negligence on the part of the mudarib in a mudarabah contract, the funds become a liability of the mudarib. Not merely does this not cover normal cases of default; it raises significant problems of enforcement—for example, in proving misconduct or negligence.

13. For more details, see Al-Deehani and colleagues (1999).

14. For other types of restrictions, see AAOIFI (1993, paras 12, 13).

15. Shareholders receive the profit generated from investing the other sources of funds because, in case of loss, providers of these funds are compensated from the shareholders’ equity.

16. For more details see Udovitch (1970) and AAOIFI (1996, 1997).

17. See, for example, Shamil Bank of Bahrain EC v Beximco Pharmaceuticals Ltd. (2004, EWCA Civ. 19) which did not concern “misconduct and negligence” but the application of a murabahah contract where U.K. law was stipulated as the governing law.

18. According to Udovitch (1970, 171), “the investor [IAH] might calculate that a larger total sum in the venture would increase the opportunities of profitable trading activities, or he might feel that the agent’s [Islamic bank’s] direct financial stake in the transactions would make him at once more cautious and more enterprising.” See also Al-Deehani and colleagues (1999) for more details on the theoretical underpinnings of this proposition, and also Williamson (1996) on “hostage posting.”

19. This is not the case, for example, in Kuwait Finance House, where the method of allocating profits between IAH and the bank pools the revenues, including those generated from investing the excess of current accounts, and expenses. The residual is allocated between the IAH and the bank. However, the pool does not include the revenues and expenses relating to investments solely funded from the shareholders’ funds.

20. If it were the case that the management placed IAH funds in less risky investments which nevertheless offered a competitive rate of return on a risk-adjusted basis, then there would be no grounds for critisism. Given the lack of transparency, however, it is hard to know whether this is the case.