Chapter 7

Foundations for Your Financial Table

Every investment has unique characteristics, some good and some bad. Like people, some are temperamental and easily influenced by the ebbs and flows of the general economy while others just go with the flow, no matter what is happening.

Matching Beliefs to Your Asset Choices

When selecting appropriate investment classes to build the various legs of your financial table, one of the most important questions to ask yourself is what is your temperament? Are you a gambler who likes the excitement of possibly doubling your money with the next roll of the dice, or do you seek stability, wanting nothing but consistency in your life?

Once suitability is established, many investments are worth considering, and sometimes having a mixture of the extremes and everything in between is the answer. The aggressively investing young hotshot looking to double his money may potentially benefit by looking at some consistently performing thoroughbreds, and the 95-year-old widow may benefit from looking at some potentially inflation busting quarter horses. The bottom line for any portfolio is balance, and from experience, I feel that the portfolios with the most legs or potential for “checks in the mail” are the most successful ones.

Let’s say you have 20 different legs or sub-legs on your financial table. Maybe check number three drops one month, but checks numbers eight and number fourteen rise that same month. Overall, you are still in the ballpark of what your Wealth Code portfolio model estimated for income that particular month or year, even though some investments have not performed as well as hoped. This is not unlike some advisors methods for equity portfolio design—a blend of beta (or risk) across the investment choices to help smooth out the ride.

Always remember the Wealth Code Golden Rule. The only guarantee in finance is something will go wrong. Design your portfolio around the concept of planning for the worst and hoping for the best.

Most of us do not live in a bubble. We all exist in the same macro-economic environment and if the global economy enters another great depression, even the most well thought-out investments will most likely not work out as planned. The idea of having as many legs as possible is simply following the concept of true asset class diversification. Knowing we need many support legs to prop up our table from the legs which potentially end up breaking. More legs under the table potentially help us achieve our goals as best as possible and keep our overall financial table stable and hopefully rising.

In my opinion, the ultimate design of a portfolio will depend on the individual investor’s beliefs and past experiences. If you have always made your money in real estate and feel it is the only investment class worth its weight in salt, then adding an equipment lease trust or mutual fund probably won’t work for you. If you do not believe this investment will work, in the future you will tend to look for reasons why it is not working, and thus, the “bad” investment becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. You’re setting yourself up for disappointment by adding investments that don’t match your beliefs.

On the flip side, using investments that match your beliefs will generally provide you with a sense of calm in tumultuous times. I’ve seen the most loyal stock holders sit back, cool as a cucumber, while their portfolios of stocks and bonds were crashing 40 to 50 percent. They absolutely believed in the longevity of their positions, and nothing could rattle them.

One’s beliefs tend to be shaped by past experiences. A client came in for a consultation, and the first thing out of his mouth was the time he lost $5,000 in an oil/gas exploratory drilling program back in 1987. His previous advisor told him all these reasons for going into the position—tax benefits, huge returns, and so on—and what happened next? The single oil well project came in dry, and he got nothing but a $5,000 tax deduction. Since then, he has always told the story of why oil/gas investments are worthless and scams. I’m sure individuals like Rockefeller would disagree, but that’s not the point. For this man, unless he was open to setting aside his opinion formed over the last 20 years, oil/gas investments would most likely not be a good fit.

Time and Real Assets

A key to the successful financial performance of real assets is time and inflation. Let’s say you just inherited the Empire State Building from a long-lost family billionaire and were informed that the building had no debt on it, had net positive cash flow of a million a month, but was probably not as valuable as it was in 2007 and not a good time to sell. Would you feel compelled to sell? Would you feel anxious if you sat around collecting rents to the tune of a million a month? Probably not!

Over time, the beauty of real assets is that they tend to be worth more eventually. In the meantime, you’re enjoying the income from rents.

The nice thing about rental rates is that they tend to follow inflation. If the rent would buy 100 loaves of bread today, then in 20 years, whatever the cost of 100 loaves of bread is, the rent will usually have adjusted at the same relative ratio.

Since large commercial real estate tends to be valued based on the income of the property, the value of the building generally goes up if the income has gone up.

If time is not on your side, you potentially put yourself in a position where you will need to fire sale the property.

Fire sales are never any fun for the seller, but the cash-ready buyer will have lots of fun. If your house is worth $500,000 today and would reasonably sell for that amount if listed and marketed properly with plenty of time, how much do you think it would sell for if you were forced to sell it in the next 24 hours for cash? That is, what price would lure someone to snap up your house with a cashier’s check the next day? Would the quick sale price be $400,000 or $250,000? The answer usually falls in the 60 percent range of the fair market value of the house.

If I drive by and see a $100,000 house with a sign out front declaring fire sale, today only, the first person with $60,000 gets it, I will be running to my bank as fast as I can. Not being greedy, the day after I buy it, I list the house for $70,000 and will probably sell it rather quickly. Not bad for a day or two of work. 60 percent of fair market value is generally the quick sale value of a piece of real estate.

As an example of some of the real estate investments we work with, non-traded REITs generally have time on their side. They tend to follow the rules of low leverage, typically under 50 percent, and long-term debt, five or ten years or longer, with fixed interest rates. With cash coming in from investors and rents coming in from their properties, they have the other keys to success: cash flow and a piggy bank filled with emergency reserves. All of these factors give these REITs time. Time to wait around for the properties to eventually become more valuable.

Have we seen the share prices of the REITs fall in the last few years? Of course, as they are tied to the overall economy and almost all classes of real estate have fallen since 2006. That being said, as long as we can ride out the rough patch, collect some rent, time will help re-inflate the value of the properties to hopefully above the original share prices.

Again, anyone who has owned a home for more than 10 or 15 years knows that time on your side always helps the bottom line. This is a benefit of owning real assets (your home, other real estate, or tangible investments)—inflation works for you.

Direct Participation Programs

One way to put money into tangible assets is through investment programs called direct participation programs (DPPs). Most of the investments within the High Return-Capital Preservation (HR-CP) category are DPPs.

When you have a direct investment in tangible or real assets, such as real estate, leased equipment, and energy resources, you own a share of the actual assets of an operating company and may benefit from the assets’ value, typically the income they produce.

The most common DPPs are business development corporations (BDCs), non-traded real estate investment trusts (REITs), equipment leasing corporations, and energy exploration and development limited partnerships.

Investing through a DPP gives you partial ownership of actual physical assets. For example, if you invest in a non-traded REIT, you’re a part owner of the real estate holdings of the REIT. If you invest in an equipment leasing corporation, you’re part owner of the actual equipment offered for lease by the corporation. If you invest in a business development corporation, you’re part owner through common shares of the BDC, of the loans funding many publicly and privately traded companies. If you invest in an oil development corporation, you’re part owner of the corporation’s wells and the proceeds of oil sales.

The pooled investment structure of DPPs is sometimes described as a way to provide the average investor with opportunities previously available only to the wealthy. Because you invest as part of a group, you don’t need the means to acquire a large percentage stake in the venture or fund your own start-up company to invest in new businesses.

In each case, the sponsors who offer DPPs pool your funds with the funds of other participating investors to make investments they have identified as appropriate to the program’s investment goals. The sponsors are responsible for managing the assets of the program as long as it continues to operate and for devising an appropriate strategy for ending it (exit strategy).

The legal structures that provide the foundations for different types of direct investment programs vary. REITs are a special type of corporation. Equipment leasing businesses are structured as limited liability corporations (LLCs). Energy ventures are formed as limited partnerships. In practice, however, the investments behave as limited partnerships, regardless of their differing legal structures.

In brief, a limited partnership has a general partner, in this case the sponsor, who runs the business, and a number of limited partners who invest but aren’t involved in the partnership’s operation or liable for losses beyond their own investment.

Accreditation of Investors

While learning about the different legs on the financial table, you’ll notice several disclosures I’ve included throughout the book.

State suitability and accredited investor rules apply—not suitable for all investors.

As licensed security advisors, many of the investments I discuss in general terms are considered accredited investments. That is, the potential investor needs to meet certain net worth and income requirements to invest in these financial tools.

Working with an experienced advisor will help you understand which investments have what type of requirements and will be appropriate for your financial portfolio.

Accreditation rules generally apply to investments that have limited liquidity or liquidity requirements. The SEC wants to make sure a person has other means besides this particular investment. I fully stand behind the idea of balance and of using appropriate vehicles for an investor, but as discussed below, I question the motivation for the rules. No one should ever put all of their eggs in one basket. You need money in many different categories to be well diversified: some resources in the High Return-Liquid category, such as stocks, bonds, and mutual funds, and other money in the Capital Preservation-Liquid category, such as the bank. Access to cash is very important for a part of your money, but as previously mentioned, it is not necessarily the Holy Grail for building wealth.

Examples of investments with partial (State) accreditation standards include the typical Non-Traded REIT, Equipment Lease Trust, Business Development Corporation, Life Note, or Mortgage debenture. These financial tools will generally have a net worth requirement of $250,000 depending on the state where you live. Another way to qualify for these particular investments is to have a net worth of $70,000 and an annual income of at least $70,000. Net worth does not include a personal residence. The particular state where you live will set the accreditation rules, and discussing this with your advisor is imperative before building a successful investment blue print.

Most oil/gas and other private securities are full accreditation investments, meaning you typically need an investible net worth of $1M. Investible net worth is calculated without the equity value of your personal residence.

The other way to qualify for full accreditation is to have an income of more than $200,000 for each of the last two years, or $300,000 if you are married.

Table 7.1 categorizes the basic investment accreditation standards.

Table 7.1 Accreditation Standards

| Non-Accredited Investments | Stocks, Bonds, Mutual Funds, Annuities, Consumer Grade Real Estate |

| State Accredited Investments: $70,000 Income and $70,000 Net Worth Or $250,000 Net Worth | Non-Traded REITs and BDCs, Life Notes and Mortgage Debentures, Equipment Leasing, some Oil and Gas |

| Full Accredited Investments: $1,000,000 Net Worth Or $200,000/$300,000 Income | Most Oil and Gas, Partnerships, and Private Securities |

Other rules apply for entities such as irrevocable trusts or Limited Liability Corporations (LLCs).

Though adamant about using appropriate tools for any given investor’s financial table, I am personally torn by my beliefs of accreditation for investments. I’m torn because Wall Street is the primary driver on investment rules. You could argue that the SEC or Congress sets the rules, but I disagree. Politicians’ pockets are lined with Wall Street cash, and Wall Street wants to promote the investments that make them the most money year in and year out. If a particular investment doesn’t pay a commission that matches their criteria, then the investment will usually have accreditation standards placed on it and thus limit the ability of advisors to recommend certain ideas.

I’m the first to believe in balance and in using many concepts that are all suitable for a particular investor, but when the rules allow an 80-year old to buy as much high tech widget IPO stock as possible, yet limit their ability to add what I consider to be an extremely conservative collateralized note program with equity three times that of the notes and a strong track record over decades, I start to question the reasons for the accreditation limits. Are they meant to protect the individual from less scrupulous advisors or to protect Wall Street from losing that money to investments that are not as lucrative for their advisors?

It is most important to note that the investments I am discussing are securities registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Any investment can be a private placement or an investment not registered with the SEC, but as a licensed advisor, I only represent registered securities. Registered securities must follow the rules for disclosure and come with prospectuses. For instance, a mutual fund is a registered security, and that is why when you purchase one, you receive in the mail that big legal document most people just throw out or use to jump start a nice winter fire. However, a prospectus is very important because it tells you the information you need to evaluate an investment properly. It includes and discloses the fees, risks, management, and conflicts of interest for that particular investment.

Due diligence is the key to protecting oneself from being caught by a guy like Madoff and his $50 billion Ponzi scheme. Having registered securities provides at least a semi-transparent view of the investment. Nothing is perfect, and I’m sure there are countless examples of registered securities falling through the cracks. A great example was mortgage securities that were pitched to investors as a great alternative to cash in the bank. When the credit crunch hit in August of 2007, these “Liquid” investments became completely “Illiquid.” Yes, they came with prospectuses, but nowhere in the prospectus did they fully disclose the extent to which investments inside the fund could use toxic or esoteric mortgage pools and the risks they truly represented.

One client came to me asking for help with his daughter’s marriage. He had placed all the funds needed for the wedding in a mortgage-backed security, which was sold to him by an advisor pitching it as a great alternative to cash earning 1 percent. “Don’t worry; it is as safe as cash,” the pitchman said. “Just as liquid, also. You can sell whenever you like, since these are on the stock market!” he was told before buying it. Well, when his daughter’s wedding approached and he went to sell the security for the needed cash, to his surprise, he was told, “Sorry, no one is buying that security. You’ll have to wait.”

My answer to the gentleman was a little more complete, but not much. We discussed the secondary market for the security and that if he did want to sell, he would probably take an 80 percent or greater loss. I felt this was not the answer and advised against it. The man was stuck with a wedding he had to pay for with credit cards at 17 percent interest rates. The point is this: Just because a security is registered and has a prospectus does not guarantee that it is a good investment.

Commissions and Fees

All investments have fees and commissions. The particular kind of investment determines which is being paid. In general, when you are in the stock market, you are paying ongoing asset fees. With real assets, in general, you are paying commissions.

If you were to buy an investment rental property, say for $100,000, and you set aside $25,000 for the purchase, this would include the down payment (20 percent or $20,000) and all initial loan costs, inspections, appraisals, and miscellaneous purchasing expenses. In this example the other costs total $5,000.

Your net cash flow is the amount left after all ongoing expenses, such as property management, property taxes, mortgage payment, and so forth, have been paid. For this example, let’s say it is $4,000.

To figure out your net cash flow percentage, simply divide the net income, $4,000, by the initial investment, $25,000.

The result is around 16 percent. That is the beauty of leverage and using other people’s money.

All investments, one way or another, have ongoing expenses, whether in the stock market or in real assets.

With real assets, not all the money used for the purchase is going to buy the dirt/asset. In the previous example, only $20,000 is going into the ground, the down payment. The other $5,000 covers the miscellaneous expenses to acquire the property. You might call these the commissions earned by the various parties involved, such as the appraiser, the home inspector, and the mortgage consultant.

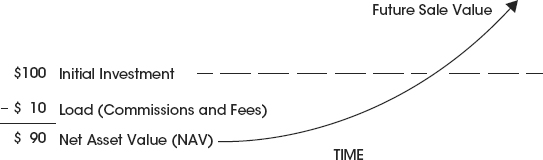

When purchasing securities that are part of the High Return-Capital Preservation category, not all of your money goes to buy the real asset. Commissions are paid to the various people or groups involved, including the real estate or real asset agents, the appraisers, the sponsor, and the financial advisors who recommended this investment to you. For example, if you invested $100, maybe only $90 goes into the ground/assets. Your statement, however, will reflect $100 as your balance, not $90, and if the dividend for a particular investment is 7 percent, you will see $7 of dividends paid to you that year.

The key to this category is time. The sponsor knows that it takes time for the real asset to appreciate to earn back the 10 percent or $10 paid as commissions to the various parties. They will need time for the actual ground/asset to gain value above the $100 you put in as your initial investment (see Figure 7.1). Once the property is stabilized, the rents/distributions from the real assets will cover the dividends, but the asset’s appreciation is the only thing that will cover the original costs to get into the investment.

Figure 7.1 Time/Growth Overcoming Investment Fees

Of note and to revisit the leak in the bucket previously discussed, I believe the main reason the larger wire houses will not represent the majority of the investment classes in the High Return-Capital Preservation category is because of the one-time commission aspect. A mutual fund or variable annuity is much more profitable in the long run due to the internal ongoing fees that are paid by the investor each year, whether the investor is making money or not. This is compared to a single commission paid on a real asset security investment that might take years to go full cycle—to potentially return the principal and growth back to the investor not counting the dividends—and to free up the money to be re-invested somewhere else.

Only if the result is positive would most investors in the commission oriented investments reward the adviser by keeping the money with them, which then allows the financial advisor to make another commission. It is all about the Benjamins, they like to say.

Prioritization and Placement of Portfolio Investments

Something I hear time and time again from other advisers is “don’t put a tax advantaged investment inside a tax deferred vehicle such as an IRA or 401(k).” The logic behind this is if an investment has tax advantages, they are being theoretically wasted inside the deferred vehicle and the client will not receive the benefits. Advisers will often regurgitate the inappropriateness of using an tax deferred annuity or tax advantaged piece of real estate inside an IRA or other retirement vehicle because, again, you are “double” tax deferred and potentially wasting the tax benefits. When I design a portfolio recommendation for a client, I prioritize the possible investment choices according to the client’s resources and income needs. Resources are defined as how much pre-tax and after-tax money the client has available as part of their investable net worth.

The first thing I do is match the types of investments or legs on the table to the amount of investment dollars I’m working with. For example, $100,000 might be four investments while $1M could be as many as 20 different investments.

I consider each potential investment to be used in a portfolio by the following prioritization:

- What is the expected potential income and growth

- What is the expected liquidity and flexibility

- What are the tax advantages

If the client has all their money in retirement accounts, then tax advantages don’t necessarily matter. Any income generated will be fully taxed.

If a client has a mixture of both types of money, then after the first two prioritizations are satisfied, then and only then do I consider the tax benefits and the ultimate placement of the investment. That is, should a particular investment go into a pre-tax account or an after-tax account.

Look at the three considerations for an investment. First and foremost, whether an investment is going into a pre-tax or after-tax account, the bottom line is whether it can potentially have a good return. That is priority number one. Who cares if something is double deferred by placing it into a retirement account. If that investment has the potential to bring home the bacon and is suitable for the client, use it.

I have heard many advisers say you should only put investments with loss potentials in after-tax accounts because if they lose, at least the client will be able to write off the loss. A quick reminder to the reader; ALL investments can lose your money. That fact alone negates this erroneous concept.

Second, once I believe an investment is suitable and has the potential to generate a return, then I consider the liquidity of that investment. This is priority number two. Liquidity will determine if a particular investment is better situated in a pre-tax retirement account or an after-tax account.

Many illiquid investments can work well inside a retirement account because the investor’s goals usually don’t require them to need access to the principal, just the potential income. Liquidity is not their concern so investments in the high return–capital preservation category are natural fits.

I try to maximize more liquid investments such as the adaptive managers in the stock market or the illiquid investments with shorter expected durations in the after-tax accounts. This is done for the simple reason of access to principal and tax consequences. If a client calls me up needing $50,000 for a new car, after-tax money is a far better resource to pull from than pre-tax dollars as the pre-tax dollars will most likely cause a larger tax consequence.

Finally, the third priority for an investment and where to position it, whether in a pre-tax or after-tax account, is the tax advantages. Does the investment come with perks such as depreciation, depletion, deferral, and so forth?

If all things are basically equal and I’ve picked two investments for a client’s portfolio that I believe will have roughly the same potential return and the liquidity is comparable, I’ll focus the investment with greater tax advantages in the after-tax pool of money. A Business Development Corporation which generally will not have any tax advantaged income will work better in an IRA than a non-traded REIT because the REIT should generally provide depreciation offsets on its distributions. If the client is pulling income from both investments, by using the REIT in the after-tax account, the total reportable income should be lower and thus lower the eventual tax bill.

In Summary

Becoming a competent carpenter requires a strong understanding of the basics of woodworking and craftsmanship. Something as simple as which types of glues work best with which types of woods is an example of understanding the basics.

The foundational concepts for The Wealth Code portfolio can be thought of as the glue for each investment leg on your financial table and are vital to beginning to build your portfolio’s blue print as described in the next chapter.

Understanding the effects of inflation and time on tangible investments, how fees and commissions are paid, and access to private securities known as DPPs gives one a more diverse playing field to choose from when designing their custom portfolio.