Chapter 5

Leaks in the Bucket

Imagine you’re in the desert. Your car has broken down, and you need to fill the radiator with water. Your family is getting hot sitting in the car but, fortunately, you see a gas station just a short walk away. You grab your handy bucket out of the trunk and head out to fill it with water.

After finding the water hose, you start to fill your bucket. Soon, you notice the water level in the bucket isn’t rising, although the water is flowing into the bucket. You then notice that your toes are starting to squish inside your shoes and that there are several small leaks in your bucket and the water is draining out as fast as it is pouring in.

Everyone has a bucket that represents his or her financial net worth. Everything you own—your income, liabilities, taxes, and investments—makes up your financial bucket. The benefit of a leak-proof financial bucket is to hold and preserve your wealth and hopefully to allow it to expand and grow.

It is an important goal of any financial plan to plug potential leaks. But leaks happen, and leaks prevent the bucket from serving its purpose. These leaks vary in size, but the result is the same. They prevent you from filling up your financial bucket efficiently. You could have three financial quarts poured in while one quart is leaking out. Or in too many instances, people’s financial buckets are more like three quarts in and four quarts out. Most people are going backward.

Common leaks in one’s financial bucket are caused by a variety of factors including limited investment asset-class diversification and taking on the wrong types of risk; by inflation, hidden investment fees, and taxes; withdrawing too much income from a portfolio, and poor estate planning and asset protection. The biggest leak of all is usually the result of not following plain old common sense and letting emotion and irrationality overtake logic and reason.

These leaks threaten to drain your financial bucket over time, forcing you to either save more, work harder or for a longer period of time, or risk running out of money. All are choices that are never fun and make retirement planning more difficult.

Not Following Common Sense

“It is the obvious which is so difficult to see most of the time.”

Isaac Asimov

“Common sense is not so common.”

Voltaire

Almost all of the leaks in one’s bucket can be attributed to a divergence from common sense. Cognitive dissonance can be a killer in financial portfolios. That is, being unwilling to keep an open mind in light of contrary evidence which suggests a better pathway or approach to investing. This stubbornness is the rust that creates the holes in your bucket.

A perfect example of this is when emotions are high, as they are during an extended stock market decline. Clients will come in and frequently state they need to sell some investments to raise cash. Granted, raising cash for something like a margin call is one thing, a forced need of immediate cash, but usually these clients want to sell because they are afraid everything is going down. Most of the investments I favor are not in the stock market and are generally not affected when the markets go down. That being said, the client usually wants the security of selling some winning positions to ease the pain of their losing positions.

This is a classic example of something I call “firing the wrong investment.”

I clarify this concept to my clients using a simple story.

Imagine you are the owner of a construction site and you have two types of workers. Little skinny workers who sit around all day and stir up problems with gossip, and big strong workers who work from dawn to dusk and never complain about anything. You pay both types of workers the same amount.

If you are in a budget crunch, who are you going to fire first?

The lazy skinny workers, right?

That is common sense.

Yet, say you have a stock which is losing money and causing you heart palpitations. Selling your winning stock or investment to make yourself feel better is the same as firing the big strong worker when there’s a budget crunch. Such action will only compound your problems on the construction site.

The same applies to one’s investments. The losing positions are losing money for a reason, and keeping them while getting rid of winning ones is only going to cause bigger and bigger holes in your retirement bucket.

Getting rid of the losing positions and clearing your head are the right choices for preserving and reinforcing your wealth.

Limited Investment Diversification

Most financial programs, magazines, newspapers, blogs, and the like say that to be diversified you need many types of stocks, bonds, and mutual funds. Some even add annuities to the mix.

Most advisors offer only these asset classes due to their training, licensing, and limited exposure. Many follow plans that are very linear. A leads to B leads to C, and so on. Also, the majority of financial advisors were trained by the big wire houses and believe these investments are the only games in town. If you look in the yellow pages for financial advisors and brokerage firms, you will notice they are all basically the same.

My background is in science. My undergraduate degree is in Biochemistry, and it taught me to think in terms of how the body protects itself from harm, as well as how to look at problems from a different perspective. I think of it as cause and effect. What are the causes we are dealing with today, and what effects are most likely to result?

May I suggest a homework assignment? Ask your advisor a simple question. “What is going on today and how is my portfolio designed to withstand any problems on the horizon?” Sit back and critique the answer. If it is unresponsive or sounds similar to the sound bites you hear on CNBC, maybe it is time to find another advisor, one who spends more time reading about what’s going on in the economy and the world as it relates to finance, and who would manage your portfolio accordingly. Financial advisers are paid for this very purpose, aren’t they? They must have a deep knowledge of what is going on in finance today!

Here’s an example of how the body protects itself and how we apply this cause and effect concept to finance. If a guy goes outside in only his boxers and falls asleep in a lawn chair on a sunny day, we know what will probably be the outcome. One, his neighbors will probably call the cops, and two, he’ll have a painful sunburn. It won’t make sitting on the cold concrete in jail very comfortable.

What has happened to him? He has damaged his skin all the way down to the DNA. The four base pairs of DNA are Adenine, Guanine, Cytosine, and Thymine. These are the building blocks of the DNA double helix. The problem with a sunburn, or more accurately UV exposure, is that it causes the Thymine base pairs to bond together forming what is called a T-T dimer. Long story short, parts that are not supposed to stick together are now sticking together.

The amazing thing about the body is that it has the means to repair itself. Little guys go in and fix the T-T dimer, unstick it so to speak, and we’re back in business. If the little guys that go in to fix the problem don’t do the job, our bodies have backup systems to make sure the problem is taken care of.

To relate to this story, there are no backup systems when most financial advisors believe that stocks, bonds, mutual funds, and annuities are the only investments a person needs. In 2008, it didn’t matter what you owned; almost everything was drastically impacted in the second worst year in the history of the stock market.

Clients of all ages were coming in with every type of portfolio imaginable: all stocks, all mutual funds, all bonds, all variable annuities, and every mix in between. They all got hammered. A 92-year-old man came in to my office with a portfolio of muni-bond funds. “Well diversified and ultra conservative,” his advisor had told him. The gentleman asked for my opinion. I told him, “If you were well diversified, per your advisor, why then did your portfolio drop from $1,100,000 to $764,000? A drop of more than 30 percent.” His answer, “I’m not really diversified, am I?”

Bonds are to Wall Street what CDs are to a bank—the conservative choice and the only choice they have to offer you.

The problem again is the point of view of the person defining something as conservative.

I was flying back to Los Angeles a few years back, and sitting next to me was a pilot returning home. She was not piloting this flight, mind you, just catching a ride home as a fellow passenger. Going from Las Vegas to Los Angeles, we flew over the desert on takeoff. The dry winds really create havoc for most planes, causing a lot of turbulence. I made an interesting observation. My knuckles were dead white, hers a nice mellow shade of pink. In fact, she was sipping a cup of tea, not even appearing to think twice about the rough turbulence we were experiencing. I said to her, “No big deal, huh?” Her response, “A walk in the park. If it gets bad, I’ll let you know.” Though somewhat comforting, I still had the feeling of pending doom.

Her definition of “turbulence” was very different from mine. I feel most financial advisors’ definitions of risk are very different from the average investor’s. Most advisors promote their version of conservative, which they say are bonds, variable annuities, or index mutual funds, and when the markets lose 40 percent and the bonds only lose 15 percent, then that is a conservative investment.

My definition of a conservative investment is not something that ONLY loses 15 to 20 percent!

In 2012, something I’ve run across often is the notion that bonds are the only true conservative investment. Most advisors have been in the business less than 30 years and their perspective on bonds reflects the fact that they have only seen a bond bull market.

Understanding the basic relationship bonds have to interest rates is imperative. Basically when interest rates fall, bonds increase in value and vice versa. See Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1 Interest Rates versus Bond Values

Many shrewd investors are still puzzled by this relationship between interest rates and bond values. The basic idea is, if you are trying to sell a bond you own, does another investor see your bond as appealing or not.

To cement this fundamental principle, let’s use an example.

Assume you paid $100,000 for a bond paying 5 percent interest. If the current market interest rates are 5 percent, then you should have no problem selling the bond for around the same value. That is, your bond is paying the going rate.

$100,000 at 5 percent = $5,000 interest paid. $5,000 is what a potential buyer would expect to receive in interest for a current $100,000 bond, so you can sell for pretty much the same value you paid.

If interest rates go down, say to 3 percent, then for another investor, your bond, which is paying 5 percent, is more appealing. You will need to be compensated for the higher yield your bond pays, and thus you can more likely sell your bond for more than the $100,000 you originally paid.

$100,000 at 3 percent = $3,000 interest paid. Your bond is paying $5,000 so to be compensated your bond should sell for around $140,000.

$140,000 at 3 percent = $5,000 interest paid.

If interest rates go up, say to 10 percent, then for another investor, your bond, which is paying only 5 percent, is not very appealing. You will need to lower the value of what you will accept for selling the bond to make it comparable to the current going rate of 10 percent.

$100,000 at 10 percent = $10,000 interest paid. Your bond is paying only $5,000, so to attract a potential buyer; you will need to lower your value to around $50,000.

$50,000 at 10 percent = $5,000.

Based on whatever the current interest rate is your $100,000 bond value will have to be adjusted up or down to pay the same amount of interest another investor could get from buying anywhere else. Time to maturity as well as bond ratings are other crucial factors in a bond value, but for this book’s simple discussion we’ll stick to the basic idea. When interest rates go up, your bond’s value goes down and vice versa.

Since early 1981, interest rates have essentially gone down and thus bonds have risen in value. To get a true picture of bonds and their risk, you need to look to the 1970s time frame to see how they performed.

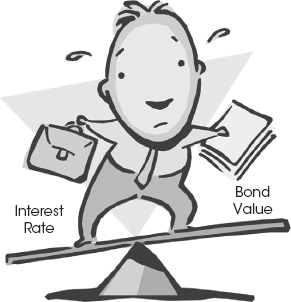

Figure 5.2 shows a graph of the Franklin U.S. Government Bond Fund, FKUSX. Very few funds show their history going back 40 years.

Figure 5.2 FKUSX 40-Year Chart

You’ll see that the fund has held its value and consistently paid a dividend since 1981. But, looking back further, you’ll see the effects of rising interest rates and inflation in the 1970s. The fund went from around $10 per share to around $6—a loss of more than 40 percent. Even with the bond bull market from 1980 to the present in 2012, the fund has never made back those losses in principal, assuming you didn’t ever reinvest your dividends.

As an aside, very few funds are still around after 40 years. Whenever a fund has a bad streak of returns, it is much easier to close the fund or absorb it into another fund and ta-da! No one can see the history of the poor performer tarnishing the image of the mutual fund family to which it belongs.

How would you feel losing 40 percent of the value of your “conservative” portfolio?

If you own a mutual bond fund and want some perspective on how it will react in the face of rising interest rates, take a look at your particular fund’s chart and put the time period between October 1998 and January 2000. This was a period when treasury yields increased by more than 1 percent.

If for instance your fund dropped around 10 percent during that period, then you have a reference point. That is, for each 1 percent increase in treasury yields, your particular mutual bond fund could fall in value roughly 10 percent. Going forward, if Treasury yields return to normal levels of around 6 percent, which is 4 percent higher than current levels today, then your particular fund could easily drop 40 to 50 percent during that rise in yields.

Again, how’s that for a “conservative” investment?

Inflation

When you read the papers and watch TV, you are bombarded with reports on how low inflation is, yet I see the indent at the bottom of the water bottle getting larger each year and the ice cream and shampoo containers getting smaller and smaller. I was curious about the cereal boxes. They looked the same. Same height, same width. Then I noticed the depth of the box was getting progressively thinner. I see movie prices going through the roof and gas prices escalating. Most people have become accustomed to $4 a gallon for gas in 2012. The price in 2006 averaged $1.50 per gallon. That’s an increase of more than 166 percent in just six years.

What would it cost to purchase the same amount of groceries in 2012 that cost one hundred dollars in 2000? It would cost $134 according to the Consumer Price Index for food and beverages.

If you don’t have an extra $34 in investments, inflation will have eaten up a good portion of your food budget, and you will need to dig into other reserves just to buy the same things.

Food for thought (no pun intended): A hundred dollars invested in the S&P500, not adjusted for inflation and without dividend reinvestment—just net of investment performance between January 1, 2000 and January 1, 2012—would be worth $91.25. Far short of the $134 you would need to buy your groceries. You’re really going to lose weight on this amount of money! An inflation diet, so to speak!

In “Hmmmmmm?”, Investment Outlook, June 2008, bond expert Bill Gross added his voice to those claiming that the CPI (Consumer Price Index, the measure by which the U.S. government reports inflation) understates the actual rate of inflation. While Gross’s analysis refers to factors such as hedonic adjustments and equivalent rental rates, the same gibberish that the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) uses in producing its data, his argument adds up to this: The United States makes adjustments to its CPI that many other countries don’t, and those adjustments don’t reflect reality.

An example of one of the “adjustments” the BLS uses and Gross was referring to is called the hedonic adjustment. Introduced in 1994 by Alan Greenspan, he argued that if you buy a washing machine for $100 and it breaks, then, when you go and purchase the exact same washing machine the next year for $120, the extra $20 doesn’t count in terms of the official inflation rate because you get at least $20 worth of enjoyment out of the new washing machine. HUH! If gasoline goes up 10 cents, we offset that with the enjoyment of clean air which is at least worth 10 cents. Only the government can think this stuff up.

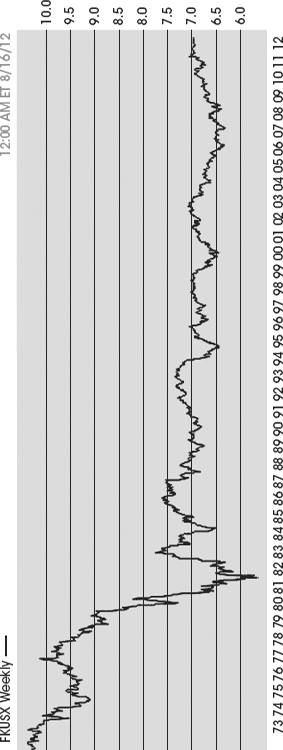

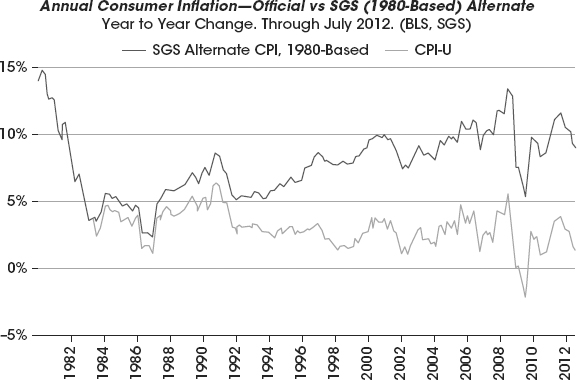

Another viewpoint is displayed in the chart in Figure 5.3.

Figure 5.3 Different Inflation Calculations (2000—May 2008)

Source: Reprinted by permission from www.shadowstats.com

The chart shows an interesting phenomenon. Over different periods, inflation has been calculated in different ways. Using the pre-1983 methodology, inflation for the first half of 2008 would be about 11.6 percent. Under the Reagan methodology, 1984 to 1998, inflation for 2008 would be 7.6 percent. Under the Clinton methodology, 1998 to present, inflation was a mere 4.1 percent.

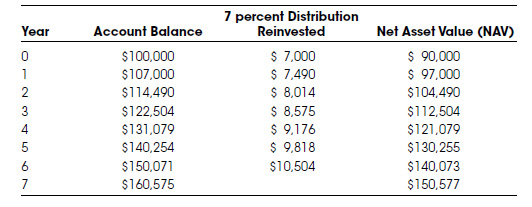

Take a look at the official CPI values versus the pre-1983 version from 1980 to 2012 shown in Figure 5.4. The most glaring part of this is that we have basically been above 7 percent going back the last 20 years. That means our money is losing purchasing power at alarming rates. The next time they tell you about those tax free muni bonds at 3.5 percent, you’ll realize even being tax free, you are still losing to inflation by more than 3 to 4 percent.

Figure 5.4 Different Inflation Calculations (1980 to July 2012)

Source: Reprinted by permission from www.shadowstats.com

Why was the system to calculate inflation changed? Simple. The United States went from a creditor nation to a debtor nation. Pre-1983, other countries owed us money. We had a vested interest in showing actual inflation. When countries borrowed from us, we wanted to be paid back in true inflation-adjusted dollars. After Reagan, when we became a net debtor nation, our focus changed to hide inflation. It was in our best interest since we owed money to other countries. Finally, 1998 under Clinton, with the unfunded liabilities of the United States growing exponentially, the calculation was changed again to hide the real inflation rate. With a lower rate, Social Security checks and Medicare reimbursement rates are lower, cost-of-living adjustments are lower, and the government can sell Treasury bonds at ridiculously low interest rates to the rest of the world and to the Federal Reserve to fund our deficits.

Whether you believe inflation is 4 percent or 12 percent, the point is it is very important to understand its effect on your retirement goals and to try to make sure you are not losing ground toward meeting those goals.

The other thing to keep in mind is the unchecked and prolific printing of U.S. dollars by the Federal Reserve. As consumers stop spending and try to increase their savings, this is counterproductive according to the Federal Reserve, and they are trying to re-inflate prices by running the printing presses at full steam ahead.

I find it fascinating to think about the history of the United States. We started as an agriculture-based economy, grew into an industrial-based economy, morphed into a consumer-service economy, and since early 2009, with the full frontal approach of quantitative easing by the Federal Reserve, descended to a Printing Press Economy. I say descended for a very good reason. When all asset classes and the economy are based on a model of printing money, the long-term outlook gets very gloomy.

Though we might experience price reductions on some capital goods due to a tightening of credit availability, don’t be fooled. The United States is setting itself up for an inflationary debacle. When people start realizing all these newly printed dollars are eroding their purchasing power, they will stop saving and start converting their money at alarming rates into tangible goods, goods that will preserve their value against a falling dollar. This rapid consumption will make the velocity of money shoot through the roof and prices will skyrocket. The velocity of money is defined as the amount of time it takes someone to spend or turn over their money. In normal times, it might take six months to spend a certain amount of money. If the velocity is increasing, they might spend faster, converting dollars into tangible goods, and only take three months to spend the same equivalent amount of money. With the velocity increasing, prices rise quickly due to greater demand for limited supplies.

Case in point, look at the hyperinflationary time between 2006 and 2009 in Zimbabwe. After the world lost faith in the ability of Zimbabwe to pay back its debts and thus stopped buying its bonds, President Mugabe did what any country’s leader in the modern world does today. He turned on the money printing press to pay for its needs. The problem of course is those newly printed bills erode the purchasing power of those printed before.

A roll of toilet paper cost $426 Zimbabwe dollars in 2006. By 2008 that same roll cost $250,000,000 and one year later it cost $100 trillion. That is $100,000,000,000,000.

Many people buy bonds with a set maturity with the belief that as long as they can hold out to the maturity date their money is safe. Though interest rates may rise and cause the value of the bond to go down, it doesn’t matter because they can wait until the maturity date to get back the full face value of their bond.

Imagine if you had purchased a $100,000 Zimbabwe dollar bond back in 2006. It could buy a good amount of toilet paper in that year. That is, the $100,000 had a significant amount of purchasing power.

Let’s say your bond matured in 2008. You are handed back your $100,000. What does it buy you in terms of purchasing power now? Not even the corner of a single sheet of toilet paper. Even though you still have your original $100,000, you have lost all the purchasing power of your original dollars. Said another way, you have lost your money. This is called the inflationary risk of bonds.

Other risks include interest rate risk, that is, rising rates will cause the bonds’ value to drop and thus force you to take a loss if you need to liquidate the bonds before the maturity date. So much for being liquid!

What if the bond issuer has issued the bond with a call option? Your bond could be called at any time before maturity. If you had planned on holding it, you’re out of luck. This is known as call risk.

My favorite risk to bonds that most people never think about is information risk. This is generally associated with municipal bonds. When you buy most any security, you are given a prospectus, the information to help you make an informed decision on that security before purchasing. When does the prospectus show up when making a purchase on a muni-bond? Generally months after the purchase. How can you know if you are buying a bankrupt municipality if you don’t have the information to make that decision when you need it? You don’t.

Another example of loss of purchasing power occurred when a lady who had all her money in certificates of deposit (CDs) came into my office for a consultation. She asked what the long-term effects of this investment strategy would be.

“Tell me something you like to do,” I asked.

“I love the movies. I go twice a week,” she replied.

“Great. If you keep all your money in CDs, over time you will have two choices,” I told her. “Your first choice is to reduce the number of times you go to the movies.”

“Never,” she replied. “I love the movies; I will be going at least twice a week forever.”

“Then,” I warned her, “choice number two is to go broke.”

Over time, her money would fall far short of her actual expenditures. Why? In her particular case, she takes out all of her interest from the CDs each year, so her principal is not growing. Without more principal to work with, as movie ticket prices—and everything else for that matter—go up, she will have to eat into the principal to maintain the same standard of living. Look at the price of movies over time. When I was a kid, they were $3. I’m sure some of you can recall the time when they were a quarter or even less. Recently, my wife and I went to the theatre and between the movie ticket price of $16.50 per ticket and one box of popcorn and parking, we were out more than $50. We’re not in Kansas anymore, Toto.

Investment Fees

A man came into my office, curious about the fees he was paying in his portfolio. He even called his advisor that morning, and his advisor told him he was in no-load mutual funds and annuities and his cost was the 1 percent annual asset fee also known as a wrap fee.

His portfolio was about $250,000, so his annual fee was $2,500. His portfolio consisted of $100,000 sitting in a money market account, $100,000 in various no-load mutual funds, and $50,000 in a variable annuity.

Starting with his money market account, I asked him if he could guess the fees he was paying. “Fees, in a money market account? There are no fees!” he told me.

Going online and finding the prospectus for his particular money market account, on the sixth page, the fees of the money market fund were clearly spelled out: 0.5 percent management fees, 0.25 percent 12-b-1 fees (marketing expenses, someone has to pay for all those beautiful brochures), and 0.30 percent misc. All added together, the fees came to 1.05 percent. Below this number was a rebate of 0.05 percent bringing the total to 1 percent. I guess they did the rebate because they didn’t want to seem like they were gouging the client on his savings!

On his $100,000 in the money market, he was paying $1,000 in fees annually, or a little over $83 per month.

Surprised, he pulled out the statements for his mutual funds. Using various resources on the web such as Personalfund.com, we broke down each of his funds.

Not only did they have management fees, but also transaction costs (these are the buying and selling commissions within the fund itself), 12-b-1 fees, and taxes for holding the fund. Taxes arising from the dividends received or reinvested if held within an after tax account. There are other invisible fees, such as soft dollar arrangements, and so on, which are usually buried in the transaction costs. Unfortunately, they don’t report the transaction costs anywhere because in theory they don’t know what they will be for the upcoming year. Isn’t that convenient?

The typical fee for this man’s mutual funds was 2 percent. Again, these were no-load mutual funds. All the “no-load” refers to is the upfront commission. It has nothing to do with the ongoing fees, which all funds charge. It is common for an advisor to sell Class-B shares that don’t have an upfront fee but include higher ongoing fees. If you sell the fund before the surrender period runs out, the remainder of the commission due will be deducted from the proceeds.

For example:

Note that the advisor is making an extra 1.25 percent each year for the Class B Fund, and over the course of four years, will have been paid the same as if you had paid the upfront commission. At this point, ethical advisors will convert the B-Shares into A-Shares so that the client isn’t paying the higher ongoing fee. The problem is that very few advisors actually convert the shares. Why do it and get paid less, right?

As a rule of rule of thumb, we don’t recommend traditional buy and hold mutual funds. If you are going to buy something to hold for a long time, buy Class A shares. Yes, you will pay more upfront, but your ongoing fees will be less.

Finally, the gentleman had a variable annuity for $50,000. Right off the bat, he said his variable was earning 7 percent per year guaranteed.

Before I addressed his statement, I showed him that the variable annuity had similar mutual fund costs within the sub-accounts, but there was also an extra layer of fees for the insurance company who issued the annuity.

The fees included Mortality & Expense (M&E) fees of 1.25 percent. This fee is basically the cost of the death benefit, which in essence will reimburse you for the principal invested if you die still holding the annuity. Said another way, if the variable annuity loses money, you are paying for life insurance to pay back the principal lost if you die still holding the annuity. Great insurance, wouldn’t you agree? You pay extra premiums to protect the insurance company from losing your hard-earned money.

Other fees include the bells and whistles for which these contracts are famous. An example was this man’s statement about his annuity being guaranteed to grow at 7 percent. Now, I’m sure he is saying exactly what his advisor told him when selling him the annuity. The problem is that the advisor told only part of the story.

His contract was guaranteed to grow by 7 percent over a 10-year period. But not the way this man thought, which was that he could pull all the money out with the guaranteed growth at the end of the tenth year. That does not apply if the contract isn’t annuitized. Basically, this 7 percent guaranteed number is only accessible if the man receives payments from the contract over his lifetime or for a minimum of 20 years. How is it possible the insurance group could guarantee a growth of 7 percent? They knew the only way the man would get this return was if he left the money with them for the 10 years plus an additional 20 years, for a total of 30 years. This was not what the man understood.

If he pulled out his money at the end of the tenth year, he would receive only what the contract was worth net of investment performance, fees, and withdrawals.

The total fees for this variable annuity averaged 4 percent or $2,000.

Fee tally on his $250,000 portfolio:

| 1 percent Advisor Wrap Fee | = $2,500 |

| 1 percent Money Market Fee | = $1,000 |

| 2 percent Mutual Funds | = $2,000 |

| 4 percent Variable Annuity | = $2,000 |

| Total Fees | $7,500 or $625 per month. |

Considering this man was living off his dividends, he was shocked to learn that he was paying approximately $625 out of his wallet each month into the pocket of this Wall Street company.

Why are fees such a big deal? Everyone deserves to make a living. We hire financial advisers for their expertise and knowledge. They are paid to do a job and deserve to be paid, as does your mechanic or doctor.

The problem is that fees can be a huge leak in the bucket if they are excessively high and continue for the life of the investment.

On a typical mutual fund held for 10 years, where fees average between 2 to 3 percent with all the hidden stuff added back in, it means you will pay approximately 20 to 30 percent out of your pocket to Wall Street just to cover fees. At the market bottom in March 2009, the stock market had essentially gone sideways for 12 years, yet most people’s portfolios were nowhere close to the level they were in 1997 due to the fees paid. If you factor in the effects of inflation, the results are even more grim.

Since 2008 up to the present in 2012, most investor’s portfolios have at best gone sideways. This is so even after the huge stock market moves and again when factoring in the fees paid since 1997. Recall the story in the beginning of the book of the potential client I met in 2012 who thought he had made a lot of money with his big-name brokerage house. After 14 years of professional management, his $367,000 investment resulted in a loss of $285! How much did the big brokerage house make in fees during that same 14 years? They probably made tens of thousands of dollars.

Take a look at your retirement funds. Have you ever wondered why you have so few choices in your 401(k), 403(b), 457, and so on? When the plan was first presented to your employer, often the choices in the plan were picked to provide the best return possible for the provider of the mutual funds. Wait, isn’t that supposed to be the best possible return for the employee? Hardly. Most mutual funds underperform the S&P500 over time spans of five years or longer. If they truly were looking out for you, they would just have you invest in general index funds with low turnover and low expense ratios.

Who do you think worked so hard to get your money into the various retirement funds? Wall Street! Most people in the 1950s had pensions, and Wall Street couldn’t get their greedy little hands on the money, so they fought the good fight, twisted a few arms in Congress to create IRA’s and 401(k)s and finally won additional retirement choices for you to put in your pre-tax dollars from work. Now, they could charge their fees and all the while fill our heads with propaganda that the stock market was the only game in town. No wonder they have been fighting to privatize social security for 50 years. They would love to get their hands and fees on that giant trust account.

One more issue to consider is an eternal debate over fee-only advisors and commission-based advisors. Fee-only advisors are advisors who charge a fixed amount for designing a financial plan, say $5,000, and market themselves as an unbiased resource. We tend to think of fee-only advisors as a bit hypocritical. If you walk in and pay $5,000 for a comprehensive plan by a fee-only advisor, you obviously trust this person to guide you accurately.

Once you have this magical plan in your hands, the dilemma then becomes how do you implement the plan? Who can put all the pieces together and turn the plan into the pot of gold. Naturally, you want to trust the person who designed the plan and will probably end up back at his or her door to implement it, thus the hypocrisy of fee-only advisors. They take off their fee-only hat and put on their wrap-fee or commission hat to put the financial investments in place and earn a second round of compensation.

A wrap-fee is the fees an adviser charges based on the amount of money they are managing for a client. The fee is “wrapped” around the assets under management (AUM).

Let’s take a look at commissionable investments, the direct placement programs (DPP) and private securities. On the surface the internal commissions paid to the advisor seem outrageous. Typically three to seven percent upfront. Many advisors point out this high upfront cost as being unthinkable and biased against the client. Actually, most of these products pay nothing ongoing, and the advisor is essentially being paid upfront to be the client’s customer service provider for as long as they are in the investment. Most of these investments are designed to be long term, three to 10 years in length. Therefore, because of the time commitment element, a commissionable investment may better serve the client versus an ongoing AUM wrap-fee model. Commission-based investments don’t have a recurring charge to the adviser for every year you are in it based on how big your account has grown. The commission is paid once, upfront.

Conversely, when assets are liquid as they are in the stock market, the AUM wrap-fee model is best. You only pay fees during the time you are in the investments. If you move the money somewhere else, the fees stop.

A key point to understand about most of the DPP programs is the commission is built into the original investment. Your distributions are paid based on the initial contribution amount and not on the initial contribution minus the load (commissions and fees) of the DPP.

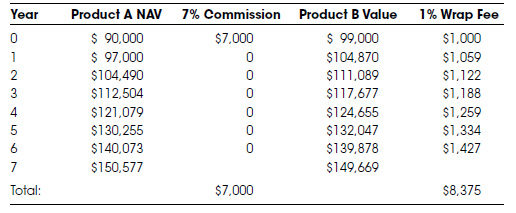

Before I show the difference between commissions paid and wrap fees paid to an adviser, it is important to understand how the true value of a DPP is calculated.

If a client invests $100,000 into a DPP, there are two values to consider: the account balance, which the distributions are based on, and the net asset value (NAV), the initial investment minus the upfront sales load. This is the true value of the real assets inside the investment, what was actually bought with the remaining money after the load is taken away.

In this hypothetical example assume the load is 10 percent, (7 percent commission plus 3 percent fees), the distribution is 7 percent, and the share price remains stable over a term of seven years. If a client was to reinvest their distributions their account would look like Table 5.1.

Table 5.1 DPP Account Balance versus NAV

The goal of the DPPs is to eventually sell for the account balance value but I like to work with the assumption the investment will only be able to sell for the NAV. In this case, the client would have $150,577 at the end of the investment’s seven-year term.

Now let’s go back to the topic of actual fees paid between investments that are either commission oriented or wrap-fee based.

In a wrap-fee based account, your fees are deducted each year from your account balance.

The best way to see the differences paid in fees is to look at the above example investment through the eyes of the adviser and his or her wallet.

Assume two hypothetical investments both last seven years and by either reinvestment of distributions or appreciation, the balance increases by 7 percent per year. The commission is 7 percent upfront for Product A and Product B has a wrap fee of 1 percent up front based on the account balance. Lastly assume the price per share for Product A stays level during the term of the investment (see Table 5.2).

Table 5.2 DPP versus Wrap Account Fee Comparison

At the end of the investment period, the client who is being billed annually at 1 percent by the wrap-fee adviser actually pays more in fees than the upfront cost of the commission based product. This is because the 1 percent is compounding based on the increasing account balance whereas the upfront single commission is based on the initial contribution.

I feel all clients should be in a mix of stock market investments as well as non-stock market investments depending of course on the results of your suitability analysis. Each comes with its own compensation model, either wrap-fee based (stock market) or commission based (non-stock market).

I believe that the best advisors are paid a combination of these types of compensation models and are upfront with the investor about it. It is the only way to effectively help people invest their money. By using a combination of payment models, an advisor can pick the ideas that make the most sense for the client instead of for the advisor’s business model. As the investor, make an informed decision about the costs by asking lots of questions.

Income, Income, Income

How often have you heard that a reasonable withdrawal rate from a portfolio is around 4 percent? Study after study shows that pulling out more than this amount in a portfolio of stocks and bonds will likely erode the principal in the long run and risk your retirement nest egg.

I propose that stock portfolios, and now with rising interest rates for the foreseeable future, bond portfolios, are not designed for generating income and should only be used for growth purposes and liquidity needs.

Wall Street will always tell you that the markets average 10 percent. This is not true. The S&P500 from January 1871 to June 2012 has averaged 8.8 percent, with full dividend reinvestment. If you were taking out dividends for income, then the S&P500 returned a measly 4.14 percent. That’s far short of the magic 10 percent number and represents over 140 years in the market. Not many of us have the potential to invest over THAT time horizon.

What most advisors don’t know, won’t tell you or frankly ignore is that there have been periods when the S&P500 averaged 0 percent. During the previous bear markets, 1881–1921, 1929–1954, and 1965–1982, these were extensive periods in history when you made nothing in the stock market.

The cover of Business Week, August 1979, said it best: “The Death of Equities.” Why? Because the markets had gone up and down for the previous 14 years like a roller coaster and kept returning to where they began.

Here in mid-2012, the average investor is burned out on the emotionally driven volatility of the markets. We had a negative 26 percent start to 2009 swing completely around into a positive 26 percent finish due to the printing press of the Federal Reserve. A flash crash-laden 2010 followed by a violent rollercoaster in 2011, with an August to September crash that rivaled all crashes going back to 1932.

As quoted from the New York Times in September 2011.

“The last few years have been the most volatile for all of recorded history.”

The inherent problem with pulling income from volatile equity portfolios is the compounded effect in bad years.

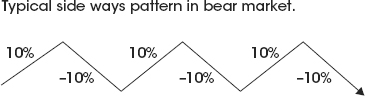

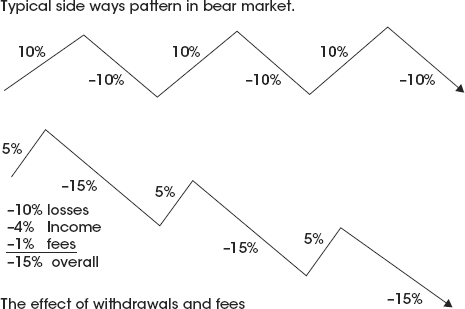

Assume the markets go back and forth for several years in a row: 10 percent up and 10 percent down. Back and forth, back and forth as you see in Figure 5.5.

Figure 5.5 Sideways Market—No Fees or Withdrawals

Each year, you pull out the same amount of income from your account. How about the universal 4 percent that Wall Street recommends?

On top of the 4 percent you are taking for income, assume your fees are 1 percent a year.

The long-term effect is that the growth of your account is stunted in the good years and the losses are compounded in the bad years.

In the good years, you make 10 percent but then take out 4 percent for income and 1 percent for fees, leaving only 5 percent overall growth in the account.

In the bad years, you lose 10 percent, and with the 4 percent withdrawal for income and 1 percent fees, your overall portfolio has dropped 15 percent (see Figure 5.6). This path is unsustainable, and before long, you will run out of money.

Figure 5.6 Sideways Market Result with Withdrawals and Fees

There is another dilemma people face when only using equity portfolios for income needs. It is their flight or fight emotional response. When the market is going down, the flight or fight response kicks in, and people usually feel a lot of stress when pulling money out of their accounts. They don’t want to compound the losses and thus will sacrifice their standard of living so as not to pull out too much from their accounts. Then in good years, they often will take out too much because they feel they are making up for a bad year, and thus, they diminish the long-term growth potential of their nest egg.

The result is the same: A lot of unnecessary stress because their money has been positioned in the wrong type of investments to meet their goals. The best investments for income purposes are the ones designed to provide the potential for income streams without causing market-driven wide swings in the principal balance.

Many of the investments we’ll discuss in Chapter 6 and Appendix B are investments that are designed to generate cash flow, and, since the principal is not tied to the stock market, you don’t necessarily see wild fluctuations in price. You may see your principal vary with changes in value of the underlying tangible asset, but they generally are not market or emotionally driven. When investments are not subject to wild fluctuations, people tend not to panic, and they allow their money to work over time. One of the biggest reasons most investments don’t work out is due to the fear/greed cycle and irrationality of buy/sell decisions.

Buy high, sell low never pays!

Taxes

If a lawyer and an IRS agent were both drowning and you could only save one of them, would you go to lunch or read the paper?

I’ve always loved this joke as it demonstrates the attitude most people have in wanting to deal with either attorneys or the IRS agent who is potentially going to audit you or your business. The sad reality is, in order to build your wealth and most importantly keep it, you need to embrace both of these individuals.

Taxes are a giant leak in one’s bucket. Everything from income to estate taxes is a drain on your wealth bucket each year and even after you kick the bucket. Uncle Sam is always looking for his take. There is nothing wrong with that, but to quote Arthur Godfrey, “I’m proud of paying taxes; the only thing: I could be just as proud for half the money.”

Pay the tax you are legally obligated to pay, just don’t leave a tip!

Quoting the Honorable Learned Hand, U.S. Appeals Court Justice, 1914:

“Over and over again Courts have said there is nothing sinister in so arranging one’s affairs as to keep taxes as low as possible. Everybody does so, rich and poor, and all do right, for nobody owes any public duty to pay more than the law demands. Taxes are enforced exactions, not voluntary contributions. To demand more in the name of morals is mere cant.”

He continued with the most astute observation I use when thinking about clients and their tax bills.

“There are two systems of taxation in our country: one for the informed and one for the uninformed.”

Most people depend so heavily on their CPA for tax advice that they forget this person is so bogged down with all the duties of just figuring out their tax bill that he or she doesn’t usually spend a lot of time helping clients truly reduce their tax bills. That is a job for a tax attorney with help from a financial advisor. How many people reading this book can think of a sit-down with their advisor where they discussed tax strategies and were educated on possibilities?

Most financial advisors will never bring up the issue of income tax planning because of two primary reasons. First they are not paid a commission or fee for discussing taxes, so why bother? Second, they are not well informed in tax planning because they don’t think of it as a worthy investment.

Investing in tax reduction education and planning is just as valid an investment as putting your money in a piece of real estate or a stock. The outcome of income tax planning is usually far more consistent than any other type of investment.

Would you put $15,000 into a stock if you had a very high degree of certainty this stock would grow to $45,000 over the next year? Most would probably say of course.

How many readers would pay a tax attorney $15,000 for the goal of achieving $60,000 in income tax savings? Far fewer in my experience. The thought of paying fees of $15,000 seems outrageous to most people, yet the result of this “investment” is the same. You will have an additional $45,000 in your pocket at the end of the year over and above the $15,000 fee the attorney charges.

Which pathway is more reliable? Does the IRS make you pay anticipated quarterly payments on the potential profit you will make if you buy a stock today? Of course not. Only if the stock goes up and you sell, thus triggering the gains, will you pay the tax.

The IRS does make you pay quarterly payments based on your previous year’s income. So if they are so certain you’ll make roughly the same amount the next year and force you to pay the tax in advance, investing in income tax education and planning generally is a far more consistent and reliable investment than any stock, piece of real estate, or other common investment one might make.

My reason for helping clients think outside the box is simple. Take care of the client, and they will take care of you. If I can show a client in conjunction with their CPA how to save $10,000 in taxes by using a simple C-Corp for their business and deducting some expenses they had been paying with after-tax dollars before, they now will have an extra $10,000 in their pocket for their enjoyment, not Uncle Sam’s.

What might the client use the newfound $10,000 for? If they don’t plan on spending it, maybe they hand it back to us for investment purposes. What goes around comes around.

On the topic of Certified Public Accountants (CPAs), Enrolled Agents, and so forth, these people are a vital part of your financial team, but please understand their general background. They are tax pros. Many times, clients will say, “I have to consult with my CPA on whether this investment makes any sense.” I encourage it but also jokingly say, “After you consult with your tax person, you should consult with your mechanic and maybe even your doctor.”

The reason I say this is that your mechanic and doctor probably know as much about these investments as your CPA does, so their opinions are probably just as valid. Your CPA may not understand these investments, and in turn give terrible advice because he or she has no idea what we’re talking about. He or she may even automatically say that the investment is bad. If you think about their errors and omission insurance, it only covers tax issues, not investment advice. If a CPA is being cautious, it is in their best interest to recommend against these ideas because if something does happen in the future, they can come back and say they didn’t recommend the investment and it is not their fault. The best CPAs will generally be upfront about this issue. They will say something like, “The investment is outside my area of expertise. You should consult with other financial advisors to get an informed second opinion.”

If you feel you need a second opinion on an investment portfolio or idea and are not sure who to ask, feel free contact me at 800-737-8552, or go to the book’s web site at www.TheWealthCode.com. I’ll be happy to give you my two cents worth.

COMMON SENSE CONCEPT

COMMON SENSE CONCEPTTaxes and investments go hand in hand. Many of the best investments have huge tax savings tied to them. For example, you have a small rental house, and in a given year you receive $10,000 in rental income. That same year on your tax return you deduct the depreciation of the house, for instance $10,000, against the rental income. In this situation, you have enjoyed $10,000 of rental income in your pocket and do not owe a dime in income taxes.

Compare that to the person who has $10,000 in CD interest income. If they were in the 30 percent tax bracket, they would only have $7,000 to enjoy after the $3,000 in taxes due.

Now, the person who was able to use depreciation to offset the rental income will have a lower cost basis for their rental property. But if they eventually sell the investment home and use an IRS Section 1031 tax-deferred exchange to get into another property of equal or greater value, no tax will be due. If that person eventually passes away, their estate will receive a step-up in the cost basis of the investment home, and the capital gains and recapture taxes that were due disappear. This is one way the rich get richer. They understand The Wealth Code on taxes and how to best preserve their nest eggs and pass them from generation to generation without the government taking half or more.

Poor Estate Planning

How is it possible for someone like Henry J. Kaiser, Jr., to die with an estate of $55,910,373 and only lose $1,030,415 in estate costs, while someone like Elvis Presley, who died with only $10,165,434 lost $7,374,635 or 73 percent to estate costs and taxes? The difference is estate planning, another huge leak in the bucket.

Most people do not realize the implications that death has on an estate. Usually something as simple as a living trust in the appropriate states, or wills in those states where those are more appropriate, would save countless hours of aggravation and money drained from an estate in probate court fees, attorney’s fees, and so forth.

One reason people give for not having the proper estate plans in place is the initial cost. This is unfortunate and shortsighted.

One client with an estate more than $15M called me after sitting with a highly qualified estate tax attorney I had recommended. He told me he was outraged by the price the attorney would charge to implement a solid estate plan. In this case, the total cost was about $8,000. I reminded the client that he would be saving about $3M in estate taxes by using the plan. Still, the client was so focused on the “outrageous” $8,000 that he never implemented the plan.

Penny wise and pound foolish, as the saying goes. By focusing only on the cost, the client lost sight of the goal. Said another way, would you invest $8,000 in a mutual fund if it was assured of returning $3M in profits? Of course, this is a no brainer. Why then would it be unthinkable to spend $8,000 on attorneys’ fees up front to get a big binder of paperwork that in the long run would save $3M in estate taxes?

A good exercise is to ask yourself two or three questions, depending on your situation.

If you are single:

- What happens financially if you are incapacitated tomorrow and cannot work?

- What happens to your loved ones financially if you die tomorrow?

If you are married:

- What happens financially if you or your spouse becomes incapacitated tomorrow and cannot work?

- What happens to your spouse financially and estate-tax wise if you die tomorrow?

- What happens to your children or beneficiaries in terms of taxes and financial well-being when the second spouse passes away?

Most people have never asked themselves these questions. It can be difficult to talk about such things as becoming incapacitated or dying. It’s easier to push that topic to another day.

There is a saying that the only thing in life that is guaranteed is that tomorrow is not guaranteed!

People usually say death AND taxes are inevitable, but I’m not so sure about the taxes if proper estate and income tax planning is adopted.

Here’s a sad reality. Dying with a large IRA can potentially cost 79 percent of the account in taxes.

Assume you have a $10M estate with $1M in an IRA. You die in 2012. Under the current tax laws, the estate pays the death taxes of 35 percent on the IRA balance, in this case $350,000. Then, if not properly designated, the beneficiary receiving the $1M IRA has to declare it for income tax purposes. In California with a state income tax of 9 percent and with the Federal top rate of 35 percent, you would lose 44 percent of the $1M, or $440,000.

Adding both taxes together, the $1M IRA has paid taxes of $350,000 and $440,000. For a total of $790,000 or 79 percent lost. Is this what you really intended to happen?

Please do not let this happen to your estate. There are several ways you can offset a lot of the taxes due by proper beneficiary designations and using allowable deductions. For instance, offset some of the taxable income by the amount of estate tax paid. If you have a large IRA and you have a large estate, please seek competent counsel on how to properly pass it to your spouse or next generation without Uncle Sam taking the lion’s share. Why save for your whole life only to have the biggest beneficiary be the government because of being uninformed and having poor estate planning. Poor estate planning is a giant leak in the bucket.

Appendix C covers the concept of discounted Roth IRA conversions, the ability to convert large IRAs to a tax-free Roth IRA at a fraction of the reportable income conventionally assumed. This is a section of this book not to be missed if you have a large pre-tax retirement account such as an IRA or 401(k).

Poor Asset Protection

I read a story about an elderly lady who gave her grandson $16,000 for his 16th birthday. My first thought was wow, don’t we all need a grandmother like that. What does the grandson do? He buys his first car of course. This is where this happy story gets ugly.

The grandson unfortunately causes an accident and hurts some people. They in turn hire a contingent-paid attorney (an attorney who gets paid only if there is a successful judgment), and sue. They don’t sue the kid. They don’t sue his parents as it is found out they really don’t have any money. They sue the grandmother for making a negligent gift to a minor and the result is a judgment which cleans out her assets putting her in the poor house.

Your first thought should be, “How can that be true? That’s not right.”

You are correct, morally or even ethically it is not right, but when it comes to civil lawsuits, there is no right or wrong. It is what it is.

As with income or estate tax planning, asset protection is also a tool the wealthy understand well. They pay for competent advice while the vast majority of individuals and businesses remain woefully ill-informed. Many clients think that just because they have a revocable living trust they are protected from a lawsuit. This is not correct. A revocable living trust is your alter-ego with the same tax id number. It can be sued as easily as you can be.

An unexpected leak in your bucket is poor asset protection. Any day you are driving on the road, or conducting your business, is a day an accident can happen and you can have everything you have worked your entire life to save and invest taken from you.

How many people own a small rental property personally? That is, they have the title of the property in their names and not in a separate entity such as a Limited Liability Company (LLC) or Corporation. The day a tenant trips on a weed in the front yard is the day you get sued. Again, not that it is your fault that Mother Nature put a weed on the grass, but because you own the grass that weed grew on.

COMMON SENSE CONCEPT

COMMON SENSE CONCEPTA common way of protecting your assets is to get a general liability umbrella policy. They are extremely cheap and in general a good thing to have. There is one problem though, and it revolves around the idea of low hanging fruit—something which is easily attained with minimal work.

If you are sued and the contingent-paid attorney does an asset discovery and finds your umbrella policy, he knows he will get paid. For instance if you have a $1M policy, that attorney knows he will get his roughly 35 percent contingent fee, or $350,000. If he knows he will get that, it is worth taking on the case and going for everything else you have. That is gravy on top of the $350,000 he knows he will get paid.

The key to asset protection is making it very difficult to be sued and more importantly to collect on any successful judgment.

Said another way, I want my estate so well guarded by various entities (LLC’s, Corporations, Foreign Trusts, etc.), that the opposing attorneys after their discovery of the assets and holdings of one’s estate realize they will have very little opportunity to collect and thus very little opportunity to get paid. They will either not take the case or they will immediately try to settle for pennies on the dollar.

Either one of these outcomes is desirable for the person being sued. It puts him or her in the driver’s seat instead of at the mercy of opposing council.

This is when an umbrella policy is a fantastic bargaining chip for a lawsuit because in general it will be the only thing the suing party can go after, and even then they will have to fight for it.

There are many great books and online resources for educating yourself on asset protection. Poor asset protection can be one of the most devastating leaks in the bucket because it can come out of nowhere and ruin your financial as well as emotional well-being.

Liquidity

Every day you hear the importance of liquidity with your money. A more complete description of this leak will be covered in Chapter 6, but, for now, a simple discussion will suffice.

While giving presentations at night to clients and potential clients, I used to ask for a show of hands. Who has had a $50,000 emergency that required pulling out money the very next day? This emergency does not include medical bills, which can be paid over time or a new car purchase on a whim, but something tragic, like your favorite uncle has been kidnapped and you need $50,000 in cash the next day to save him.

People always say they have tons of money in the bank for that “what if” emergency. The problem is that those “what if” emergencies rarely if ever happen and you are stuck with money sitting in the bank earning nothing. You are incurring opportunity costs. That money could be working harder for you, but since you keep a large chunk for that rare emergency, you rationalize it is ok to earn 1 percent because it is for peace of mind.

I have asked this emergency funds question to more than 10,000 people who attended my workshops over the years, and only six people ever raised their hands. Some people’s emergencies were at the $30,000 level, and more at the $20,000 or $10,000 level, but rarely at the $50,000 amount. They just haven’t experienced such emergencies.

Wall Street will always say that an investment that is liquid is usually considered a better investment than one that is not. I disagree. Liquidity to me means the investment is far more prone to emotional decisions, for instance, decisions made under duress or panic. An example would be when the markets are getting killed, people are always heard saying they sold at the bottom, right before the market turned up. When I wrote the first edition during March of 2009, the Dow Jones Industrial Average was at 6629 on March 7, 2009. In the papers and on TV, everyone was screaming about the average going to 3000 or 2500, the previous support levels dating back to 1984.

To quote my first edition book that was written on March 7, 2009, page 49.

“The sad part is, we are probably at the bottom of the downturn of the market. When people become so afraid and everyone is selling, that is usually the time to buy.”

As it turned out, the bottom hit on March 9, 2009.

It was almost preordained that the masses were panic selling at the bottom. Again, all the talking heads were screaming about the market breaking the October 2002 low of 7200 and that the sky was falling with no end in sight. I saw dozens of prospective clients during this period and almost all had sold to cash very close to the eventual bottom at the recommendation of their advisors.

Illiquid investments provide a buffer from the irrational decisions we humans are prone to make. Since one can’t sell even when all seems lost, the investments will usually have time and the potential to regain any lost value and become profitable.

A good example would be the drop in value owners experienced on their personal residences bought pre-1990, the last residential real estate market top before the 2006 real estate top. Most homes decreased in value from 1990 to 1994, but because it wasn’t easy to sell a home due to the general illiquidity, owners ended up riding it out, and over time, the house became worth a lot more. An advantage of owning tangible investments, as long as you are not forced to sell in the bad times, is their ability to appreciate in value over time due to inflation.

The illiquidity of the home provided a buffer, making it difficult to sell at the bottom, say in 1994, preventing the owner from making a bad investment choice. Stocks don’t have the luxury of being illiquid. They can be sold on a whim, when one’s emotions are in control, which often leads to those who buy the tops, and those who sell the bottoms, taking terrible losses, in panic.

Let us re-address this enormous leak in the bucket, liquidity, in Chapter 6, after a more complete discussion of the different investment classes available to you and the general characteristics of each one.

COMMON SENSE CONCEPT

COMMON SENSE CONCEPTSummary: Leaks in the Bucket

We all have financial buckets that represent our net worth. Unfortunately, we also have numerous leaks in our buckets that drain off money each year and reduce the size of our nest eggs. Leaks include everything from excess taxes, estate planning, limited investment choices, and fees. Fortunately, once the leaks are identified, you can begin plugging them. As more and more of the leaks get plugged, you will find that your bucket will fill more quickly with even the slightest gains. Recognizing the problem is the hardest part, but that is the purpose for the solutions we present in the upcoming chapters.