Chapter 1

Why Pricing Is the Key to Your Success

Of all the marketing problems you face in launching a new product, pricing is the most important—and the most difficult!

Want proof?

If your new product costs you, say, $45 to produce, and you sell it for $69, your profit—what you can take home with you—is $24.

- If you price that same product $10 higher, you get to pocket the entire $10 extra—resulting in $34 profit instead of $24.

- If you price your product $10 lower, you lose out of your pocket the full $10—resulting in $14 profit instead of $24.

If you sell more of your products, the profit is reduced by your costs of making the extra products. For example, you get an extra sale that brings in $45, but only $24 of that is actual profit.

Raise Prices—or Sell More Products?

Ask most businesspeople what they could do to dramatically increase their profits, and their answers are usually:

- Increase my advertising

- Add more salespeople

- Add incentives to buy more

All three strategies would probably sell more products, but they are risky. The first two will increase your costs—for which you hope to then get a payoff in increased sales and (hopefully) profits. The third strategy will lower your profit margin, so you’re earning less per unit sold.

Yet these three answers miss the most obvious way to dramatically increase profits: a price raise.

Let’s analyze what is best for profits—10 percent more sales (units) or a 10 percent higher price.

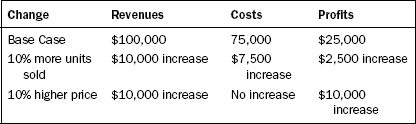

If you are currently selling $100,000 worth of a product, take a look at Exhibit 1.1 to see what would happen.

EXHIBIT 1.1 PRICE EFFECT ON PROFITS

Only with pricing does everything—plus or minus—fall to the bottom line.

You may object to Exhibit 1.1. You might figure that if you raise prices you will sell fewer products. That happens often, but not always.

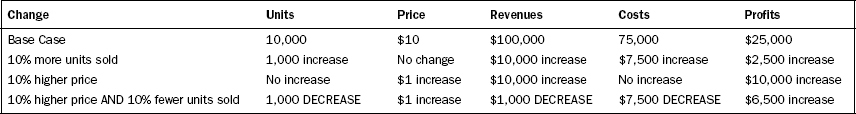

So let’s look at the same situation—if your units sold were to drop 10 percent when you raise prices 10 percent. Now it would look like Exhibit 1.2.

EXHIBIT 1.2 PRICE EFFECT ON PROFITS

Note that in Exhibit 1.2, you’d have:

- $2,500 more profits—selling 10 percent more units

- $10,000 more profits—with a 10 percent higher price

- $6,500 more profits—with a 10 percent higher price even if it lowered units sold by 10 percent

What has that meant for companies? What could it mean for you? Typically, with the cost structure at most companies, a 1 percent increase in price yields a 12 percent gain in profits (Dolan and Simon, 1996).

There’s simply no marketing decision you can make with as strong an impact on your profits as pricing.

Big-Company Case History

When Volkswagen launched the [new Beetle] in the United States, orders flooded in, quickly resulting in consumers waiting nine months for a car. The value customers placed on owning a new Beetle, coupled with the nostalgic effect, was clearly underestimated, and one could make the assumption that a $500 or $1,000 higher price might not have affected sales dramatically but would have significantly increased profits.

Butscher and Laker, 2000

Can you imagine the impact an extra $1,000 in the U.S. price would have had for Volkswagen (VW)? They sold 83,000 new Beetles in the U.S. in 1999. That means whoever picked the price for it may have lost Volkswagen $83 million in profits. Not just in sales—but in profits. And this only counts the first year, not subsequent years.

Yet in Germany, VW had the opposite problem. Their sales were poor due to a “steep” price that Butscher and Laker say overestimated the value Germans put on the car.

Another example is the launch of the Wii. Demand was so strong for the product that stores had waiting lists to get one. An extra $50 on the price wouldn’t have harmed sales at all. Instead consumers lucky enough to buy a Wii were able to resell immediately at a profit of $100 or $125 over the company’s price. So profits that could have (should have?) gone to Wii, went instead to scalpers!

Be sure you don’t throw away money like this!

Tiny-Company Case History

When I launched my first newsletter (Ancillary Profits) I wasn’t very smart about pricing. I knew that $100 was perceived as much bigger than $99 and I came out of the magazine publishing industry, not newsletters. In the magazine industry $20 was a big price. So I priced Ancillary Profits at $97—without even testing other prices.

Fortunately, I decided three months later to test higher prices. In addition to $97, I tested $117 and $127. The winner was $127. It not only gave me $30 more per subscription, but it even brought in 11 percent more orders. That means I was able to pocket 45 percent more profits from just a $30 price increase.

And I was still being stupid. The highest price I tested won. I should have tested even higher. When I did, I was able to get more profits from a $147 price! (Later, even more from $197.)

I calculated how much I lost from not starting at the higher price—and found I’d lost about $38,000 in profits. And if I hadn’t done the three tests within 12 months, it would have been much, much more. Moral of the story: Always test a price that is much higher than you think you can get.

Hopefully, you’re now convinced at how important pricing is to your bottom line.

The problem is that good pricing can be difficult. So difficult that most smaller companies just throw up their hands and take one of two “easy” ways out (both of which can cost you a lot of money!):

- Cost-plus pricing

- Match-your-competitors pricing

We’ll cover cost-plus and match-your-competitors pricing strategies in the next chapter.