CHAPTER THREE

WHAT MAKES PUBLIC ORGANIZATIONS DISTINCTIVE

The overview of organization theory in Chapter Two brings us to a fascinating and important controversy. Leading experts on management and organizations have spurned the distinction between public and private organizations as either a crude oversimplification or an unimportant issue. Other very knowledgeable people have called for the development of a field that recognizes the distinctive nature of public organizations and public management. Meanwhile, policymakers around the world struggle with decisions—involving trillions of dollars’ worth of assets—about the privatization of state activities and the proper roles of the public and private sectors. Figure 1.2 asserts that government organizations’ status as public bodies has a major influence on their environment, goals, and values, and hence on their other characteristics. This characterization sides with those who see public organizations and managers as sufficiently distinct to deserve special analysis.

This chapter discusses important theoretical and practical issues that fuel this controversy and develops some conclusions about the distinction between public and private organizations. First, it examines in depth the problems with this distinction. It then describes the overlapping of the public, private, and nonprofit sectors in the United States, which precludes simple distinctions among them. The discussion then turns to the other side of the debate: the meaning and importance of the distinction. If they are not distinct from other organizations, such as businesses, in any important way, why do public organizations exist? Answers to this question point to the inevitable need for public organizations and to their distinctive attributes. Still, given all the complexities, how can we define public organizations and managers? This chapter discusses some of the confusion over the meaning of public organizations and then describes some of the best-developed ways of defining the category and conducting research to clarify it. After analyzing some of the problems that arise in conducting such research, the chapter concludes with a description of the most frequent observations about the nature of public organizations and managers. The remainder of the book examines the research and debate on the accuracy of these observations.

Public Versus Private: A Dangerous Distinction?

For years, authors have cautioned against making oversimplified distinctions between public and private management (Bozeman, 1987; Murray, 1975; Simon, 1995, 1998). Objections to such distinctions deserve careful attention because they provide valuable counterpoints to invidious stereotypes about government organizations and the people who work in them. They also point out realities of the contemporary political economy and raise challenges that we must face when clarifying the distinction.

The Generic Tradition in Organization Theory

A distinguished intellectual tradition bolsters the generic perspective on organizations—that is, the position that organization and management theorists should emphasize the commonalities among organizations in order to develop knowledge that will be applicable to all organizations, avoiding such popular distinctions as public versus private and profit versus nonprofit. As serious analysis of organizations and management burgeoned early in the twentieth century, leading figures argued that their insights applied across commonly differentiated types of organizations. Many of them pointedly referred to the distinction between public and private organizations as the sort of crude oversimplification that theorists must overcome. From their point of view, such distinctions pose intellectual dangers: they oversimplify, confuse, mislead, and impede sound theory and research.

The historical review of organization theory in the preceding chapter illustrates how virtually all of the major contributions to the field were conceived to apply broadly across all types of organizations, or in some cases to concentrate on industry. Throughout the evolution described in that review, the distinction between public and private organizations received short shrift.

In some cases, the authors either clearly implied or aggressively asserted that their ideas applied to both public and private organizations. Max Weber claimed that his analysis of bureaucratic organizations applied to both government agencies and business firms. Frederick Taylor applied his scientific management procedures in government arsenals and other public organizations, and such techniques are widely applied in both public and private organizations today. Similarly, members of the administrative management school sought to develop standard principles to govern the administrative structures of all organizations. The emphasis on social and psychological factors in the workplace in the Hawthorne studies, McGregor’s Theory Y, and Kurt Lewin’s research pervades the organizational development procedures that consultants apply in government agencies today (Golembiewski, 1985).

Herbert Simon (1946) implicitly framed much of his work as being applicable to all organizational settings, both public and private. Beginning as a political scientist, he coauthored one of the leading texts in public administration (Simon, Smithburg, and Thompson, 1950). It contains a sophisticated discussion of the political context of public organizations. It also argues, however, that there are more similarities than differences between public and private organizations. Accordingly, in his other work he concentrated on general analyses of organizations (Simon, 1948; March and Simon, 1958). He thus implied that his insights about satisficing and other organizational processes apply across all types of organizations. In his more recent work, shortly before his death, he emphatically asserted that public, private, and nonprofit organizations are equivalent on key dimensions. He said that public, private, and nonprofit organizations are essentially identical on the dimension that receives more attention than virtually any other dimension in discussions of the unique aspects of public organizations—the capacities of leaders to reward employees (Simon, 1995, p. 283, n. 3). He stated that the “common claim that public and nonprofit organizations cannot, and on average do not, operate as efficiently as private businesses” is simply false (Simon, 1998, p. 11). Thus the leading intellectual figure of organization theory clearly assigned relative unimportance to the distinctiveness of public organizations.

Chapter Two also showed that contingency theory considers the primary contingencies affecting organizational structure and design to be environmental uncertainty and complexity, the variability and complexity of organizational tasks and technologies (the work that the organization does and how it does it), organizational size, and the strategic decisions of managers. Thus, even though this perspective emphasizes variations among organizations, it downplays any particular distinctiveness of public organizations. James Thompson (1962), a leading figure among the contingency theorists, echoed the generic refrain—that public and private organizations have more similarities than differences. During the 1980s, the contingency perspective evolved in many different directions, some involving more attention than others to governmental and economic influences (Scott, 2003). Still, the titles and coverage in management and organization theory journals and in excellent overviews of the field (Daft, 2013) reflect the generic tradition.

Findings from Research

Objections to distinguishing between public and private organizations draw on more than theorists’ claims. Studies of variables such as size, task, and technology in government agencies show that these variables may influence public organizations more than anything related to their status as a governmental entity. These findings agree with the commonsense observation that an organization becomes bureaucratic not because it is in government or business but because of its large size.

Major studies that analyzed many different organizations to develop taxonomies and typologies have produced little evidence of a strict division between public and private organizations. Some of the prominent efforts to develop a taxonomy of organizations based on empirical measures of organizational characteristics either have failed to show any value in drawing a distinction between public and private or have produced inconclusive results. Haas, Hall, and Johnson (1966) measured characteristics of a large sample of organizations and used statistical techniques to categorize them according to the characteristics they shared. A number of the resulting categories included both public and private organizations.

This finding is not surprising, because organizations’ tasks and functions can have much more influence on their characteristics than their status as public or private. A government-owned hospital, for example, obviously resembles a private hospital more than it resembles a government-owned utility. Consultants and researchers frequently find, in both the public and the private sectors, organizations with highly motivated employees as well as severely troubled organizations. They often find that factors such as leadership practices influence employee motivation and job satisfaction more than whether the employing organization is public, private, or nonprofit.

Pugh, Hickson, and Hinings (1969) classified fifty-eight organizations into categories based on their structural characteristics; they had predicted that the government organizations would show more bureaucratic features, such as more rules and procedures, but they found no such differences. They did find, however, that the government organizations showed higher degrees of control by external authorities, especially over personnel procedures. The study included only eight government organizations, all of them local government units with functions similar to those of business organizations (for example, a vehicle repair unit and a water utility). Consequently, the researchers interpreted as inconclusive their findings regarding whether government agencies differ from private organizations in terms of their structural characteristics. Studies such as these have consistently found the public-private distinction inadequate for a general typology or taxonomy of organizations (McKelvey, 1982).

The Blurring of the Sectors

Those who object to the claim that public organizations make up a distinct category also point out that the public and private sectors overlap and interrelate in a number of ways, and that this blurring and entwining of the sectors has advanced even further in recent years (Cooper, 2003, p. 11; Haque, 2001; Kettl, 1993, 2002; Moe, 2001; Weisbrod, 1997, 1998).

Mixed, Intermediate, and Hybrid Forms.

A number of important government organizations are designed to resemble business firms. A diverse array of state-owned enterprises, government corporations, government-sponsored corporations, and public authorities perform crucial functions in the United States and other countries (Musolf and Seidman, 1980; Seidman, 1983; Walsh, 1978). Usually owned and operated by government, they typically perform business-type functions and generate their own revenues through sales of their products or by other means. Such enterprises usually receive a special charter to operate more independently than government agencies. Examples include the U.S. Postal Service, the National Park Service, and port authorities in many coastal cities; there are a multitude of other such organizations at all levels of government. Such organizations are sometimes the subjects of controversy over whether they operate in a sufficiently businesslike fashion while showing sufficient public accountability. These hybrid arrangements often involve massive financial resources. In 1996, the U.S. comptroller general voiced concern over the results of audits by the General Accounting Office (GAO, now called the Governmental Accountability Office) of federal loan and insurance programs. These programs provide student loans, farm loans, deposit insurance for banks, flood and crop insurance, and home mortgages. The programs are carried out by government-sponsored enterprises such as the Federal National Mortgage Association (“Fannie Mae”). The comptroller general said that the GAO audits indicated that cutbacks in federal funding and personnel have left the government with insufficient financial accounting systems and personnel to monitor these liabilities properly. The federal liabilities for these programs total $7.3 trillion. Since the comptroller general made his assessment, experts continued to point to accountability issues that these organizations pose, because they tend to have relative independence from political and regulatory controls and can use their resources to gain and even extend their independence (Koppel, 2001; Moe, 2001).

These conditions exploded in 2007 and 2008, as part of the financial crisis described at the beginning of this book. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac played major roles in the crisis, although experts heatedly debate the nature of their involvement and how much they contributed to the crisis. Critics claimed that government officials had for years emphasized providing low-income citizens with access to mortgage money to use in buying homes, and Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac served as primary vehicles for implementing this policy. The critics contend that the policy led these two quasi-governmental organizations to extend large amounts of mortgage money to people who could not afford to make their mortgage payments. More important, they said, in implementing the policy Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac encouraged private banks to follow the same pattern, and the banks poured massive amounts of money into mortgage loans to people who could not afford them. It seems crazy that such organizations would make so many bad loans, but the organizations made money by pooling the mortgage payments into investment vehicles and selling them like bonds or notes to investors. Investors from around the world bought these “collateralized debt obligations” and related types of investments, and the banks had the incentive to keep extending more and more mortgages to people who could not afford them. Ultimately, the holders of the mortgages began to default on them, and this system of investments collapsed, causing huge losses for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and even greater losses for the private banks and financial institutions. The depth and severity of these losses is unclear at the time of this writing, and stories in the news media describe government policymakers’ and bank executives’ serious consideration of having the federal government take substantial amounts of control over one or more of the largest private financial corporations in the United States, by buying large proportions of the corporations’ stock.

Some economists and financial experts defend Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, contending that they did not play as great a role in the crisis as critics claim, because they had standards that prevented them from extending as many bad mortgage loans as did the private corporations. Whatever the case, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac both faced financial collapse and had to be taken over and restructured by government officials. During 2008, the stock price of Fannie Mae declined from about $70 per share to $1 per share. It is hard to avoid interpreting that item of information as anything other than a disaster for stockholders. Whatever the magnitude of the role of the government-sponsored corporations in precipitating the crisis, one can hardly provide a more dramatic example of their importance.

On the other side of the coin are the many nonprofit, or third-sector, organizations that perform functions similar to those of government organizations. Like government agencies, many nonprofits obviously have no profit indicators or incentives and often pursue social or public service missions, often under contract with the government (Weisbrod, 1997). To further complicate the picture, however, experts on nonprofit organizations observe a trend toward commercialization of nonprofits, by which they try to make money in businesslike ways that may jeopardize their public service missions (Weisbrod, 1998). Finally, many private, for-profit organizations work with government in ways that blur the distinction between them. Some corporations, such as defense contractors, receive so much funding and direction from government that some analysts equate them with government bureaus (Bozeman, 1987; Weidenbaum, 1969).

Functional Analogies: Doing the Same Things.

Obviously, many people and organizations in the public and private sectors perform virtually the same functions. General managers, secretaries, computer programmers, auditors, personnel officers, maintenance workers, and many other specialists perform similar tasks in public, private, and hybrid organizations. Organizations located in the different sectors—for example, hospitals, schools, and electric utilities—also perform the same general functions. The New Public Management movement that has spread through many nations in recent decades has taken various forms but has often emphasized the use in government of procedures similar to those purportedly used in business and private market activities, based on the assumption that government and business organizations are sufficiently similar to make it possible to use similar techniques in both settings (Barzelay, 2001; Ferlie, Pettigrew, Ashburner, and Fitzgerald, 1996; Kettl, 2002).

Complex Interrelations.

Government, business, and nonprofit organizations interrelate in a number of ways (Kettl, 1993, 2002; Weisbrod, 1997). Governments buy many products and services from nongovernmental organizations. Through contracts, grants, vouchers, subsidies, and franchises, governments arrange for the delivery of health care, sanitation services, research services, and numerous other services by private organizations. These entangled relations muddle the question of where government and the private sector begin and end. Banks process loans provided by the Veterans Administration and receive Social Security deposits by wire for Social Security recipients. Private corporations handle portions of the administration of Medicare by means of government contracts, and private physicians render most Medicare services. Private nonprofit corporations and religious organizations operate facilities for the elderly or for delinquent youths, using funds provided through government contracts and operate under extensive government regulation. In thousands of examples of this sort, private businesses and nonprofit organizations become part of the service delivery process for government programs and further blur the public-private distinction. Chapters Four, Five, and Fourteen provide more detail on these situations and their implications for organizations and management (Moe, 1996, 2001; Provan and Milward, 1995).

Analogies from Social Roles and Contexts.

Government uses laws, regulations, and fiscal policies to influence private organizations. Environmental protection regulations, tax laws, monetary policies, and equal employment opportunity regulations either impose direct requirements on private organizations or establish inducements and incentives to get them to act in certain ways. Here again nongovernmental organizations share in the implementation of public policies. They become part of government and an extension of it. Even working independently of government, business organizations affect the quality of life in the nation and the public interest. Members of the most profit-oriented firms argue that their organizations serve their communities and the well-being of the nation as much as governmental organizations do. As noted earlier, however, observers worry that excessive commercialization is making too many nonprofits too much like business firms. According to some critics, government agencies also sometimes behave too much like private organizations. One of the foremost contemporary criticisms of government concerns the influence that interest groups wield over public agencies and programs. According to the critics, these groups use the agencies to serve their own interests rather than the public interest.

The Importance of Avoiding Oversimplification

Theory, research, and the realities of the contemporary political economy show the inadequacy of simple notions about differences between public and private organizations. For management theory and research, this realization poses the challenge of determining what role a distinction between public and private can play. For practical management and public policy, it means that we must avoid oversimplifying the issue and jumping to conclusions about sharp distinctions between public and private.

That advice may sound obvious enough, but violations of it abound. During the intense debate about the Department of Homeland Security at the time of this writing, a Wall Street Journal editorial warned that the federal bureaucracy would be a major obstacle to effective homeland security policies. The editorial repeated the simplistic stereotypes about federal agencies that have prevailed for years. The author claimed that federal agencies steadfastly resist change and aggrandize themselves by adding more and more employees. The editorial advanced these claims even at a time when the Bush administration’s President’s Management Agenda pointed out that the Clinton administration, through the National Performance Review, had reduced federal employment by over 324,000 positions and criticized the way the reductions were carried out. Surveys also have shown that public managers and business managers often hold inaccurate stereotypes about each other (Stevens, Wartick, and Bagby, 1988; Weiss, 1983). For example, the increase in privatization and contracting out has led to increasing controversy over whether privatization proponents have made oversimplified claims about the benefits of privatization, with proponents claiming great successes (Savas, 2000) and skeptics raising doubts (Donahue, 1990; Hodge, 2000; Kuttner, 1997; Sclar, 2000).

For all the reasons just discussed, clear demarcations between the public and private sectors are impossible, and oversimplified distinctions between public and private organizations are misleading. We still face a paradox, however, because scholars and officials make the distinction repeatedly in relation to important issues, and public and private organizations do differ in some obvious ways.

Public Organizations: An Essential Distinction

If there is no real difference between public and private organizations, can we nationalize all industrial firms, or privatize all government agencies? Private executives earn massively higher pay than their government counterparts. The financial press regularly lambastes corporate executive compensation practices as absurd and claims that these compensation policies squander many billions of dollars. Can we simply put these business executives on the federal executive compensation schedule and save a lot of money for these corporations and their customers? Such questions make it clear that there are some important differences in the administration of public and private organizations. Scholars have provided useful insights into the distinction in recent years, and researchers and managers have reported more evidence of the distinctive features of public organizations.

The Purpose of Public Organizations

Why do public organizations exist? We can draw answers to this question from both political and economic theory. Even some economists who strongly favor free markets regard government agencies as inevitable components of free-market economies (Downs, 1967).

Politics and Markets.

Decades ago, Robert Dahl and Charles Lindblom (1953) provided a useful analysis of the raison d’être for public organizations. They analyzed the alternatives available to nations for controlling their political economies. Two of the fundamental alternatives are political hierarchies and economic markets. In advanced industrial democracies, the political process involves a complex array of contending groups and institutions that produces a complex, hydra-headed hierarchy, which Dahl and Lindblom called a polyarchy. Such a politically established hierarchy can direct economic activities. Alternatively, the price system in free economic markets can control economic production and allocation decisions. All nations use some mixture of markets and polyarchies.

Political hierarchy, or polyarchy, draws on political authority, which can serve as a very useful, inexpensive means of social control. It is cheaper to have people relatively willingly stop at red lights than to work out a system of compensating them for doing so. However, political authority can be “all thumbs” (Lindblom, 1977). Central plans and directives often prove confining, clumsy, ineffective, poorly adapted to many local circumstances, and cumbersome to change.

Markets have the advantage of operating through voluntary exchanges. Producers must induce consumers to engage willingly in exchanges with them. They have the incentive to produce what consumers want, as efficiently as possible. This allows much freedom and flexibility, provides incentives for efficient use of resources, steers production in the direction of consumer demands, and avoids the problems of central planning and rule making inherent in a polyarchy. Markets, however, have a limited capacity to handle the types of problems for which government action is required (Downs, 1967; Lindblom, 1977). Such problems include the following:

Public goods and free riders. Certain services, once provided, benefit everyone. Individuals have the incentive to act as free riders and let others pay, so government imposes taxes to pay for such services. National defense is the most frequently cited example. Similarly, even though private organizations could provide educational and police services, government provides most of them because they entail general benefits for the entire society.

Individual incompetence. People often lack sufficient education or information to make wise individual choices in some areas, so government regulates these activities. For example, most people would not be able to determine the safety of particular medicines, so the Food and Drug Administration regulates the distribution of pharmaceuticals.

Externalities or spillovers. Some costs may spill over onto people who are not parties to a market exchange. A manufacturer polluting the air imposes costs on others that the price of the product does not cover. The Environmental Protection Agency regulates environmental externalities of this sort.

Government acts to correct problems that markets themselves create or are unable to address—monopolies, the need for income redistribution, and instability due to market fluctuations—and to provide crucial services that are too risky or expensive for private competitors to provide. Critics also complain that market systems produce too many frivolous and trivial products, foster crassness and greed, confer too much power on corporations and their executives, and allow extensive bungling and corruption. Public concern over such matters bolsters support for a strong and active government (Lipset and Schneider, 1987). Conservative economists argue that markets eventually resolve many of these problems and that government interventions simply make matters worse. Advocates of privatization claim that government does not have to perform many of the functions it does and that government provides many services that private organizations can provide more efficiently. Nevertheless, American citizens broadly support government action in relation to many of these problems.

Political Rationales for Government.

A purely economic rationale ignores the many political and social justifications for government. In theory, government in the United States and many other nations exists to maintain systems of law, justice, and social organization; to maintain individual rights and freedoms; to provide national security and stability; to promote general prosperity; and to provide direction for the nation and its communities. In reality, government often simply does what influential political groups demand. In spite of the blurring of the distinction between the public and private sectors, government organizations in the United States and many other nations remain restricted to certain functions. For the most part, they provide services that are not exchanged on economic markets but are justified on the basis of general social values, the public interest, and the politically imposed demands of groups.

The Concept of Public Values

In essential intellectual activity related to analyzing public organizations, authors have developed the concept of public values as a rationale for government and other entities to defend and produce such values. The concept is similar to concepts of market failure discussed earlier, such as public goods, externalities, and public information that protects citizens from inadequate knowledge of such matters as the health risks of pharmaceutical products. The concept of public values differs from those economics-based concepts, however. Authors developing the concept focus much less on economic market failure and more on the political and institutional processes by which public values are identified—and furthered or damaged.

Moore: Creating Public Value.

The publication about public values most frequently cited by other authors is Mark Moore’s Creating Public Value (1995). Moore implicitly defined public values by discussing differences between public and private production processes and circumstances justifying public production, and he provided many examples. Public value consists of what governmental activities produce, with due authorization through representative government, and taking into consideration the efficiency and effectiveness with which the public outputs are produced. Public managers create public value when they produce outputs for which citizens express a desire:

Value is rooted in the desires and perceptions of individuals—not necessarily in physical transformations, and not in abstractions called societies. . . . Citizens’ aspirations, expressed through representative government, are the central concerns of public management. . . . Every time the organization deploys public authority directly to oblige individuals to contribute to the public good, or uses money raised through the coercive power of taxation to pursue a purpose that has been authorized by citizens and representative government, the value of that enterprise must be judged against citizens’ expectations for justice and fairness as well as efficiency and effectiveness (p. 52).

Similarly, Moore contended that managers can create public value in two ways (1995, p. 52). They can “deploy the money and authority entrusted to them to produce things of value to particular clients and beneficiaries.” They can also create public value by “establishing and operating an institution that meets citizens’ (and their representatives’) desires for properly ordered and productive public institutions.” Public managers can behave proactively in this process. “They satisfy these desires when they represent the past and future performance of their organization to citizens and representatives for continued authorization through established mechanisms of accountability.” Public managers, Moore argued, “must produce something whose benefits to specific clients outweigh the costs of production.”

Moore thus advanced a conception of public value that one can describe as a “publicly authorized production” conception. (These quotation marks are ours, and do not indicate a quotation from Moore.) Public value derives from what governmental activities produce, with authorization from citizens and their representatives. Public value increases when the outcomes are produced with more efficiency and effectiveness. Thus Moore offered no explicit definition of “public value” except that it derives from citizen desires, and he offers no definitive or explicit list of public values.

The Accenture Public Sector Value Model.

One finds a similar perspective in the “Accenture Public Sector Value Model” (Jupp and Younger, 2004), whose authors cite Moore as a source of the concept of public value. Similarly to Moore, the Accenture model never defines public values explicitly. The authors of the model explain that public value emerges from the production of outcomes of governmental activities, considered together with the cost-effectiveness of producing those outcomes:

“Outcomes” are a weighted basket of social achievements. “Cost-effectiveness” is defined as annual expenditure minus capital expenditure, plus capital charge (p. 18).

Without considering the merits of the model, one can point out that the model and its authors do not undertake to define public values explicitly. Public values consist of outcomes based on what a government entity is supposed to be doing, and based on what citizens want it to do, taking into account. As with Moore’s conception, which influenced the Accenture model, the authors of this model offer no explicit or independent definition of public value, except as outcomes that citizens want. They, too, offer no list of public values.

Bozeman’s Public Values and Public Interest.

Bozeman, in Public Values and Public Interest (2007), advances a conception of public values and public value failure with similarities to that of Moore, but with very important differences. In previous work, Bozeman (2002a) had proposed a concept of “public value failure” as a major alternative to the concept of market failure. He argued that market failure concepts have tended to concentrate on market efficiency and utilitarianism, whereas public value failure concentrates instead on failures of the public and private sectors to fulfill core public values. Bozeman suggests a number of instances in which this can occur. For one, mechanisms for articulating and aggregating values fail when core public values are skirted because of flaws in policymaking processes. For example, if public opinion strongly favors gun control but no such policies are enacted, the disjunction between public opinion and policy outcomes fails to maximize public values about democratic representation. In another example, the public and private sectors may produce a situation involving threats to human dignity and subsistence, such as an international market for internal human organs leading impoverished individuals to sell their internal organs merely to survive. Interesting and important, the concepts of public value and public value failure further illustrate the relatively abstract nature of the rationales for government and its organizations, and in turn become significant aspects of the context for understanding and managing government organizations.

In the more recent book, Bozeman (2007, p. 13) offers an explicit definition of public values: “A society’s ‘public values’ are those providing normative consensus about (a) the rights, benefits, and prerogatives to which citizens should (and should not) be entitled; (b) the obligations of citizens to society, the state, and one another; and (c) the principles on which governments and policies should be based.” He also conceives of public values as existing at the individual level. He defines individual public values as “the content-specific preferences of individuals concerning, on the one hand, the rights, obligations, and benefits to which citizens are entitled and, on the other hand, the obligations expected of citizens and their designated representatives” (p. 14). In other words, he asserts that in societies one can discern patterns of consensus about what everyone should get, what they owe back to society, and how government should work. Individuals have their own values in relation to such matters, and the patterns of consensus consist of aggregations of those individuals who agree with each other about such matters.

This perspective resembles Moore’s in various ways. Both perspectives locate value in the preferences of the citizenry, for example. Both emphasize the production of outputs and outcomes as sources of public value. Bozeman at certain points emphasizes public value “failure,” when neither the market nor the public sector provides goods and services that achieve public values. Moore emphasized positive production of outcomes that enhance public value, but, by implication, failure to produce such outcomes fails to create or increase public value.

Differences between the two perspectives involve matters of emphasis and explicit versus implicit expression. There are important differences, however, that have implications for the relationship between this discussion and public service motivation. One way of expressing some of these differences would contend that Moore emphasized production whereas Bozeman more heavily emphasizes the demand side of the production process. As his book’s title—Creating Public Value: Strategic Management in Government— implies, Moore focused on the public manager’s production of public value, by identifying outcomes that will increase it, developing strategy for producing those outcomes, managing the political context, and designing effective and efficient operational management processes for producing the outcomes. In Moore’s analysis, public value refers generally to outcomes of value to citizens and clients, with the public value increasing as the efficiency and effectiveness of production increases. He identified outcomes only through some examples but not through an explicit listing, definition, or typology. Bozeman’s perspective more heavily emphasizes the existence of public values, independently of production processes but obviously enhanced or diminished by production processes. Moore discussed how the public manager and others (such as political authorities) decide whether government can justify producing outcomes, rather than leaving the production to the private sector. Bozeman (2007) and Jørgensen and Bozeman (2007) do not restrict the production of goods and services that affect public values to government. Public and private organizations produce goods and services that either achieve or fail to achieve public values. Hence, public values represent a psychological and sociologic construct referring to values that persons and social aggregates hold, independent of the production of goods and services that fulfill those values or violate them.

Identifying Public Values

The consideration of public values as psychological and social constructs that exist independently of production processes for outcomes that influence public values has a very significant implication. It draws Jørgensen and Bozeman (2007; also Bozeman, 2007) into an effort to identify public values. They point out that public administration scholars examining public values take a variety of approaches. One approach is to posit public values, making no pretense of deriving them. One can conduct public opinion polls, survey public managers, or locate public values statements in government agencies’ strategic planning documents and mission statements and sometimes in their budget justification documents. Another approach (Jørgensen and Bozeman, 2007) involves developing an inventory of public values from public administration and political science literature. When Jørgensen and Bozeman undertake to develop such an inventory, the list of public values becomes complex, multileveled, and sometimes mutually conflicting. The inventory includes seven major “value constellations” (Jørgensen and Bozeman, 2007) or “value categories,” (Bozeman, 2007, pp. 140–141), each containing a set of values.

The complex results of the inventory should come as no surprise. As many authors have pointed out many times, the values that organizations pursue are diverse, multiple, and conflicting, and the values that government organizations pursue are usually more so. Bozeman (2007, p. 143) contends that lack of complete consensus about public values should not prevent progress in analyzing public interest considerations. He proposes a public value mapping model that includes criteria for use in analyzing public values and public value failure. For purposes of the present discussion, however, the absence of a compact, definitive list of public values has implications for the discussion of public service motivation (PSM) that follows. As described later, much of the PSM research has pursued a conception of PSM that involves only a few references to any public values that might appear on any list or inventory. In addition, much of the PSM research has treated PSM as a general, unitary construct, of which different individuals have more or less. The complexity of the public values inventory, however, coupled with Bozeman’s assertion that public values also exist at the individual level, suggests that individuals may vary widely in their conceptions of PSM.

The Meaning and Nature of Public Organizations and Public Management

Although the idea of a public domain within society is an ancient one, beliefs about what is appropriately public and what is private, in both personal affairs and social organization, have varied among societies and over time. The word public comes from the Latin for “people,” and Webster’s New World Dictionary defines it as pertaining to the people of a community, nation, or state. The word private comes from the Latin word that means to be deprived of public office or set apart from government as a personal matter. In contemporary definitions, the distinction between public and private often involves three major factors (Benn and Gaus, 1983): interests affected (whether benefits or losses are communal or restricted to individuals); access to facilities, resources, or information; and agency (whether a person or organization acts as an individual or for the community as a whole). These dimensions can be independent of one another and even contradictory. For example, a military base may purportedly operate in the public interest, acting as an agent for the nation, but deny public access to its facilities.

Approaches to Defining Public Organizations and Public Managers.

The multiple dimensions along which the concepts of public and private vary make for many ways to define public organizations, most of which prove inadequate. For example, one time-honored approach defines public organizations as those that have a great impact on the public interest (Dewey, 1927). Decisions about whether government should regulate have turned on judgments about the public interest (Mitnick, 1980). In a prominent typology of organizations, Blau and Scott (1962) distinguished between commonweal organizations, which benefit the public in general, and business organizations, which benefit their owners. The public interest, however, has proved notoriously hard to define and measure (Mitnick, 1980). Some definitions directly conflict with others; for example, defining the public interest as what a philosopher king or benevolent dictator decides versus what the majority of people prefer. Most organizations, including business firms, affect the public interest in some sense. Manufacturers of computers, pharmaceuticals, automobiles, and many other products clearly have tremendous influence on the well-being of the nation.

Alternatively, researchers and managers often refer to auspices or ownership—an implicit use of the agency factor mentioned earlier. Public organizations are governmental organizations, and private organizations are nongovernmental, usually business firms. Researchers using this simple dichotomy have kept the debate going by producing impressive research results (Mascarenhas, 1989). The blurring of the boundaries between the sectors, however, shows that we need further analysis of what this dichotomy means.

Agencies and Enterprises as Points on a Continuum.

Observations about the blurring of the sectors are hardly original. More than half a century ago, in their analysis of markets and polyarchies, Dahl and Lindblom (1953) described a complex continuum of types of organizations, ranging from enterprises (organizations controlled primarily by markets) to agencies (public or government-owned organizations). For enterprises, they argued, the pricing system automatically links revenues to products and services sold. This creates stronger incentives for cost reduction in enterprises than in agencies. Agencies, conversely, have more trouble integrating cost reduction into their goals and coordinating spending and revenue-raising decisions, because legislatures assign their tasks and funds separately. Their funding allocations usually depend on past levels, and if they achieve improvements in efficiency, their appropriations are likely to be cut. Agencies also pursue more intangible, diverse objectives, making their efficiency harder to measure. The difficulty in specifying and measuring objectives causes officials to try to control agencies through enforcement of rigid procedures rather than through evaluations of products and services. Agencies also have more problems related to hierarchical control—such as red tape, buck passing, rigidity, and timidity—than do enterprises.

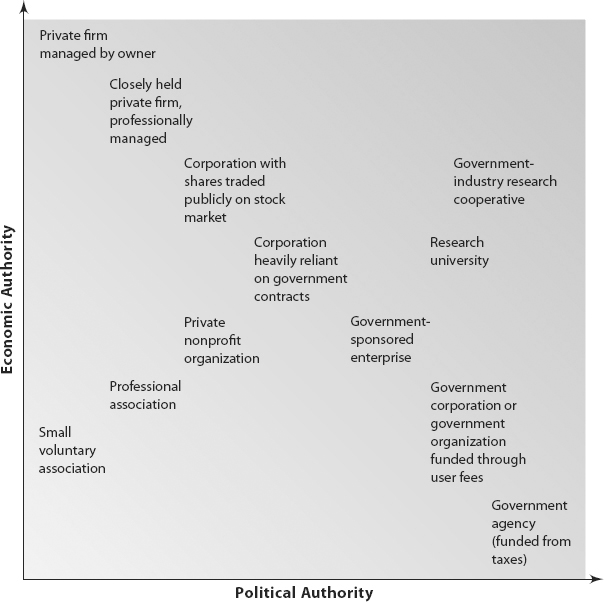

More important than these assertions in Dahl and Lindblom’s oversimplified comparison of agencies and enterprises is their conception of a continuum of various forms of agencies and enterprises, ranging from the most public of organizations to the most private (see Figure 3.1). Dahl and Lindblom did not explain how their assertions about the different characteristics of agencies and enterprises apply to organizations on different points of the continuum. Implicitly, however, they suggested that agency characteristics apply less and less as one moves away from that extreme, and the characteristics of enterprises become more and more applicable.

FIGURE 3.1. AGENCIES, ENTERPRISES, AND HYBRID ORGANIZATIONS

Source: Adapted and revised from Dahl and Lindblom, 1953.

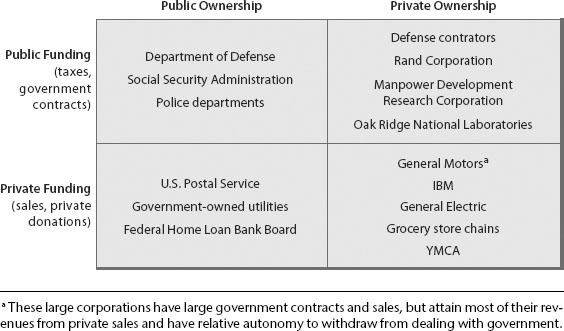

Ownership and Funding.

Wamsley and Zald (1973) pointed out that an organization’s place along the public-private continuum depends on at least two major elements: ownership and funding. Organizations can be owned by the government or privately owned. They can receive most of their funding from government sources, such as budget allocations from legislative bodies, or they can receive most of it from private sources, such as donations or sales within economic markets. Putting these two dichotomies together results in the four categories illustrated in Figure 3.2: publicly owned and funded organizations, such as most government agencies; publicly owned but privately funded organizations, such as the U.S. Postal Service and government-owned utilities; privately owned but governmentally funded organizations, such as certain defense firms funded primarily through government contracts; and privately owned and funded organizations, such as supermarket chains and IBM.

FIGURE 3.2. PUBLIC AND PRIVATE OWNERSHIP AND FUNDING

Source: Adapted and revised from Wamsley and Zald, 1973.

This scheme does have limitations; it makes no mention of regulation, for example. Many corporations, such as IBM, receive funding from government contracts but operate so autonomously that they clearly belong in the private category. Nevertheless, the approach provides a fairly clear way of identifying core categories of public and private organizations.

Economic Authority, Public Authority, and “Publicness.”

Bozeman (1987) drew on a number of the preceding points to try to conceive the complex variations across the public-private continuum. All organizations have some degree of political influence and are subject to some level of external governmental control. Hence, they all have some level of “publicness,” although that level varies widely. Like Wamsley and Zald, Bozeman used two subdimensions—political authority and economic authority—but treated them as continua rather than dichotomies. Economic authority increases as owners and managers gain more control over the use of their organization’s revenues and assets, and it decreases as external government authorities gain more control over their finances.

Political authority is granted by other elements of the political system, such as the citizenry or governmental institutions. It enables the organization to act on behalf of those elements and to make binding decisions for them. Private firms have relatively little of this authority. They operate on their own behalf and only for as long as they support themselves through voluntary exchanges with citizens. Government agencies have high levels of authority to act for the community or country, and citizens are compelled to support their activities through taxes and other requirements.

The publicness of an organization depends on the combination of these two dimensions. Figure 3.3 illustrates Bozeman’s depiction of possible combinations. As in previous approaches, the owner-managed private firm occupies one extreme (high on economic authority, low on political authority), and the traditional government bureau occupies the other (low on economic authority, high on political authority). A more complex array of organizations represents various combinations of the two dimensions. Bozeman and his colleagues have used this approach to design research on public, private, and intermediate forms of research and development laboratories and other organizations. Later chapters describe the important differences they found between the public and private categories, with the intermediate forms falling in between (Bozeman and Loveless, 1987; Coursey and Rainey, 1990; Crow and Bozeman, 1987; Emmert and Crow, 1988). Also employing a concept of publicness, Antonsen and Jørgensen (1997) compared sets of Danish government agencies high on criteria of publicness, such as the number of reasons their executives gave for being part of the public sector (as opposed to being in the public sector as a matter of tradition or for economies of scale). The agencies high on publicness showed a number of differences from those low on this measure, such as higher levels of goal complexity and of external oversight.

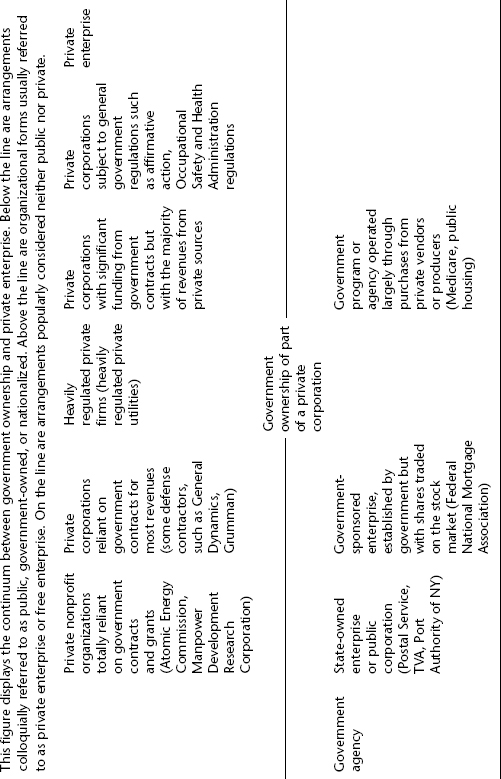

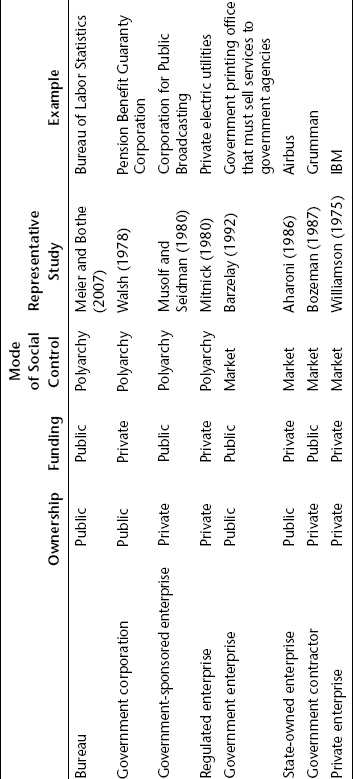

Even these more complex efforts to clarify the public-private dimension do not capture its full complexity. Government and political processes influence organizations in many ways: through laws, regulations, grants, contracts, charters, franchises, direct ownership (with many variations in oversight), and numerous other ways (Salamon and Elliot, 2002). Private market influences also involve many variations. Perry and Rainey (1988) suggested that future research could continue to compare organizations in different categories, such as those in Table 3.1.

TABLE 3.1. TYPOLOGY OF ORGANIZATIONS CREATED BY CROSS-CLASSIFYING OWNERSHIP, FUNDING, AND MODE OF SOCIAL CONTROL

Source: Adapted and revised from Perry and Rainey, 1988.

Although this topic needs further refinement, these analyses of the public-private dimension of organizations clarify important points. Simply stating that the public and private sectors are not distinct does little good. The challenge involves conceiving and analyzing the differences, variations, and similarities. In starting to do so, we can think with reasonable clarity about a distinction between public and private organizations, although we must always realize the complications. We can think of assertions about public organizations that apply primarily to organizations owned and funded by government, such as typical government agencies. At least by definition, they differ from privately owned firms, which get most of their resources from private sources and are not subject to extensive government regulations. We can then seek evidence comparing these two groups, and in fact such research often shows differences, although we need much more evidence. The population of hybrid and third-sector organizations raises complications about whether and how differences between these core public and private categories apply to those hybrid categories. Yet we have increasing evidence that organizations in this intermediate group—even within the same function or industry—differ in important ways on the basis of how public or private they are. Designing and evaluating this evidence, however, involves some further complications.

Problems and Approaches in Public-Private Comparisons

Defining a distinction between public and private organizations does not prove that important differences between them actually exist. We need to consider the supposed differences and the evidence for or against them. First, however, we must consider some intriguing challenges in research on public management and public-private comparisons, because they figure importantly in sizing up the evidence.

The discussion of the generic approach to organizational analysis and contingency theory introduced some of these challenges. Many factors, such as size, task or function, and industry characteristics, can influence an organization more than its status as a governmental entity. Research needs to show that these alternative factors do not confuse analysis of differences between public organizations and other types. Obviously, for example, if you compare large public agencies to small private firms and find the agencies more bureaucratic, size may be the real explanation. Also, one would not compare a set of public hospitals to private utilities as a way of assessing the nature of public organizations. Ideally, an analysis of the public-private dimension requires a convincing sample, with a good model that accounts for other variables besides the public-private dimension. Ideally, studies would also have huge, well-designed samples of organizations and employees, representing many functions and controlling for many variables. Such studies require a lot of resources and have been virtually nonexistent, with the exception of the example of the National Organizations Study (which found differences among public, nonprofit, and private organizations, as described in Chapter Eight; see Kalleberg, Knoke, and Marsden, 2001; Kalleberg, Knoke, Marsden, and Spaeth, 1996). Instead, researchers and practitioners have adopted a variety of less comprehensive approaches.

Some writers theorized on the basis of assumptions, previous literature and research, and their own experiences (Dahl and Lindblom, 1953; Downs, 1967; Wilson, 1989). Similarly, but less systematically, some books about public bureaucracies simply provided a list of the differences between public and private, based on the authors’ knowledge and experience (Gawthorp, 1969; Mainzer, 1973). Other researchers conducted research projects that measure or observe public bureaucracies and draw conclusions about their differences from private organizations. Some concentrated on one agency (Warwick, 1975), some on many agencies (Meyer, 1979). Although valuable, these studies examined no private organizations directly.

Many executives and managers who have served in both public agencies and private business firms have made emphatic statements about the sharp differences between the two settings (Blumenthal, 1983; Hunt, 1999; IBM Endowment for the Business of Government, 2002; Rumsfeld, 1983; Weiss, 1983). Quite convincing as testimonials, they apply primarily to the executive and managerial levels. Differences might fade at lower levels. Other researchers compared sets of public and private organizations or managers. Some compared the managers in small sets of government and business organizations (Buchanan, 1974, 1975; Kurland and Egan, 1999; Porter and Lawler, 1968; Rainey, 1979, 1983). Questions remain about how well the small samples represented the full populations and how well they accounted for important factors such as tasks. More recent studies with larger samples of organizations still leave questions about representing the full populations. They add more convincing evidence of distinctive aspects of public management (Hickson and others, 1986; Kalleberg, Knoke, and Marsden, 2001; Kalleberg, Knoke, Marsden, and Spaeth, 1996; Pandey and Kingsley, 2000) or provide refinements to our understanding of the distinction without finding sharp differences between public and private managers on their focal variables (Moon and Bretschneider, 2002).

To analyze public versus private delivery of a particular service, many researchers compare public and private organizations within functional categories. They compare hospitals (Savas, 2000, p. 190), utilities (Atkinson and Halversen, 1986), schools (Chubb and Moe, 1988), airlines (Backx, Carney, and Gedajlovic, 2002), and other types of organizations. Similarly, other studies compare a function, such as management of computers or the innovativeness of information technology, in government and business organizations (Bretschneider, 1990; Moon and Bretschneider, 2002). Still others compare state-owned enterprises to private firms (Hickson and others, 1986; MacAvoy and McIssac, 1989; Mascarenhas, 1989). They find differences and show that the public-private distinction appears meaningful even when the same general types of organizations operate under both auspices. Studies of one functional type, however, may not apply to other functional types. The public-private distinction apparently has some different implications in one industry or market environment, such as hospitals, compared with another industry or market, such as refuse collection (Hodge, 2000). Yet another complication is that public and private organizations within a functional category may not actually do the same thing or operate in the same way (Kelman, 1985). For example, private and public hospitals may serve different types of patients, and public and private electric utilities may have different funding patterns.

In some cases, organizational researchers studying other topics have used a public-private distinction in the process and have found that it makes a difference (Chubb and Moe, 1988; Hickson and others, 1986; Kalleberg, Knoke, Marsden, and Spaeth, 1996; Kurke and Aldrich, 1983; Mintzberg, 1972; Tolbert, 1985). These researchers had no particular concern with the success or failure of the distinction per se; they simply found it meaningful.

A few studies compare public and private samples from census data, large-scale social surveys, or national studies (Brewer and Selden, 1998; Houston, 2000; Kalleberg, Knoke, Marsden, and Spaeth, 1996; Light, 2002a; Smith and Nock, 1980; U.S. Office of Personnel Management, 2000). These have great value, but such aggregated findings often prove difficult to relate to the characteristics of specific organizations and the people in them. In the absence of huge, conclusive studies, we have to piece together evidence from more limited analyses such as these. Many issues remain debatable, but we can learn a great deal from doing so.

Common Assertions About Public Organizations and Public Management

In spite of the difficulties described in the preceding section, the stream of assertions and research findings continues. During the 1970s and 1980s, various reviews compiled the most frequent arguments and evidence about the distinction between public and private (Fottler, 1981; Meyer, 1982; Rainey, Backoff, and Levine, 1976). There has been a good deal of progress in research, but the basic points of contention have not changed substantially. Exhibit 3.1 shows a recent summary and introduces many of the issues that later chapters examine. The exhibit and the discussion of it that follows pull together theoretical statements, expert observations, and research findings. Except for those mentioned, it omits many controversies about the accuracy of the statements (these are considered in later chapters). Still, it presents a reasonable depiction of prevailing issues and views about the nature of public organizations and management that amounts to a theory of public organizations.

Unlike private organizations, most public organizations do not sell their outputs in economic markets. Hence the information and incentives provided by economic markets are weaker for them or absent altogether. Some scholars theorize (as many citizens believe) that this reduces incentives for cost reduction, operating efficiency, and effective performance. In the absence of markets, other governmental institutions (courts, legislatures, the executive branch) use legal and formal constraints to impose greater external governmental control of procedures, spheres of operations, and strategic objectives. Interest groups, the media, public opinion, and informal bargaining and pressure by governmental authorities exert an array of less formal, more political influences. These differences arise from the distinct nature of transactions with the external environment. Government is more monopolistic, coercive, and unavoidable than the private sector, with a greater breadth of impact, and it requires more constraint. Therefore, government organizations operate under greater public scrutiny and are subject to unique public expectations for fairness, openness, accountability, and honesty. Internal structures and processes in government organizations reflect these influences, according to the typical analysis. Also, characteristics unique to the public sector—the absence of the market, the production of goods and services not readily valued at a market price, and value-laden expectations for accountability, fairness, openness, and honesty as well as performance—complicate the goals and evaluation criteria of public organizations. Goals and performance criteria are more diverse, they conflict more often (and entail more difficult trade-offs), and they are more intangible and harder to measure. The external controls of government, combined with the vague and multiple objectives of public organizations, generate more elaborate internal rules and reporting requirements. They cause more rigid hierarchical arrangements, including highly structured and centralized rules for personnel procedures, budgeting, and procurement.

Greater constraints and diffuse objectives allow managers less decision-making autonomy and flexibility than their private counterparts have. Subordinates and subunits may have external political alliances and merit-system protections that give them relative autonomy from higher levels. Striving for control, because of the political pressures on them, but lacking clear performance measures, executives in public organizations avoid delegation of authority and impose more levels of review and more formal regulations.

Some observers contend that these conditions, aggravated by rapid turnover of political executives, push top executives toward a more external, political role with less attention to internal management. Middle managers and rank-and-file employees respond to the constraints and pressures with caution and rigidity. Critics and managers alike complain about weak incentive structures in government, lament the absence of flexibility in bestowing financial rewards, and point to other problems with governmental personnel systems. Complaints about difficulty in firing, disciplining, and financially rewarding employees generated major civil service reforms in the late 1970s at the federal level and in states around the country and have continued ever since. As noted in Chapter One, this issue of the need for flexibility to escape such constraints became the most important point of contention in the debate over the new Department of Homeland Security in 2002.

In turn, expert observers assert, and some research indicates, that public employees’ personality traits, values, needs, and work-related attitudes differ from those of private sector employees. Some research finds that public employees place lower value on financial incentives, show somewhat lower levels of satisfaction with certain aspects of their work, and differ from their private sector counterparts in some other work attitudes. Along these lines, as Chapter Nine describes, a growing body of research on public service motivation over the past decade suggests special patterns of motivation in public and nonprofit organizations that can produce levels of motivation and effort comparable to or higher than those among private sector employees (Francois, 2000; Houston, 2000; Perry, 1996, 2000).

Intriguingly, the comparative performance of public and nonpublic organizations and employees figures as the most significant issue of all and the most difficult one to resolve. It also generates the most controversy. As noted earlier, the general view has been that government organizations operate less efficiently and effectively than private organizations because of the constraints and characteristics mentioned previously. Many studies have compared public and private delivery of the same services, mostly finding the private form more efficient. Efficiency studies raise many questions, however, and a number of authors defend government performance strongly. They cite client satisfaction surveys, evidence of poor performance by private organizations, and many other forms of evidence to argue that government performs much better than generally supposed. As Chapters Six and Fourteen elaborate, in recent years numerous authors have claimed that public and nonprofit organizations frequently perform very well and very innovatively, and they offer evidence or observations about when and why they do.

This countertrend in research and thinking about public organizations actually creates a divergence in the theory about them. One orientation treats government agencies as inherently dysfunctional and inferior to business firms; another perspective emphasizes the capacity of public and nonprofit organizations to perform well and innovate successfully. Both perspectives tend to agree on propositions and observations about many characteristics of public and nonprofit organizations, such as the political influences on public agencies.

This discussion and Exhibit 3.1 provide a summary characterization of the prevailing view of public organizations that one would attain from an overview of the literature and research. Yet for all the reasons given earlier, it is best for now to regard this as an oversimplified and unconfirmed set of assertions. The challenge now is to bring together the evidence from the literature and research to work toward a better understanding and assessment of these assertions.

- Key terms

- Discussion questions

- Topics for writing assignments or reports

- Class Exercise 1: The Nature of Public Service: The Connecticut Department of Transportation