CHAPTER SIX

ORGANIZATIONAL GOALS AND EFFECTIVENESS

Organizations are goal-directed, purposive entities, and their effectiveness in pursuing those goals influences the quality of our lives and even our ability to survive. Virtually all of management and organization theory is concerned with performance and effectiveness, at least implicitly. Virtually all of it is in some way concerned with the challenge of getting an organization and the people in it to perform well. This chapter first discusses major issues about organizational goals and the goals of public organizations, including observations that other authors have made about how public organizations’ goals influence their other characteristics. Then the chapter reviews the models of organizational effectiveness that researchers have developed and discusses their implications for organizing and managing public organizations.

As previous chapters have discussed, beliefs about the performance and effectiveness of public organizations, especially in comparison to private organizations, have played a major role in some of the most significant political changes and government reforms in recent history, in nations around the world. Executives and officials in government, business, and nonprofit organizations emphasize goals and effectiveness in a variety of ways. One can hardly look at the annual report or the Web site of an organization without encountering its mission statement, which expresses the organization’s general goals. Very often one also sees statements of core values that express general objectives, and on the Web sites of many government agencies, one can review the organization’s strategic plan or performance plan, which expresses its specific goals and performance measures. All of the major federal agencies have strategic plans with goals statements or “performance plans” or both on their Web sites and in their annual reports. The Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) of 1993 directed each federal agency to develop such plans, and subsequent reports of their performance, in relation to the goals. Web sites now make available copies of all the federal agencies’ strategic plans and performance plans.

For example, on the Web site for the Social Security Administration (SSA), which in money paid out is the largest federal program, one can review the 2013–2016 performance plan (U.S. Social Security Administration, 2013). The plan provides the following summary of the agencys’s goals (p. 5):

These expressions of the goals of the SSA raise the question of how useful they are and how much influence they will have on the agency’s effectiveness. Clearly many officials and executives think such expressions have value. One now finds strategic plans and performance plans of this sort at all levels of government (Berman and Wang, 2000), in part because state legislatures have passed legislation similar to the GPRA, requiring state agencies to prepare such plans. This huge national investment in stating goals and performance measures reflects one of the strongest trends in public management in the past two decades. Authors and officials have increasingly emphasized themes such as “managing for results” that involve stating goals and measurements that reflect effectiveness in achieving the goals (Abramson and Kamensky, 2001; Moynihan, 2008; Osborne and Gaebler, 1992). There is also a movement emphasizing the integration of such goals and performance measures with governmental and agency budgets (Grizzle and Pettijohn, 2002). Melkers and Willoughby (1998) reported that forty-seven of the fifty states have some form of requirement for performance-based budgeting.

This concentration on goals and performance measures involves interesting basic assumptions. It assumes that public organizations will perform better if the people in them clarify their goals and measure progress against them. This assumption usually links to the idea that government agencies need to perform a lot better, and that they can do so by becoming more like business firms, which presumably have clearer goals and performance measures. These assumptions sound reasonable enough, but Radin (2000) points out that these and others undergirding the GPRA and related approaches at other levels of government may not work well in the fragmented, pluralistic institutional and political environments of government agencies described in the preceding chapter. The multiple authorities and actors in the system do not necessarily agree on the goals and performance criteria for public organizations, and they often do not support a rational, goal-oriented approach to decision making.

Still, the importance attached to goals, performance, and effectiveness makes it interesting and important to examine the ways in which organization and management theorists have dealt with these topics. Ironically, in relation to the emphasis that public officials have been placing on goals and measures, when one turns to the literature on organizational goals and effectiveness, one finds something of a muddle, although a very insightful one. Experts in the field have not developed clear, conclusive ways of defining organizational goals and defining and assessing effectiveness. Their use of the somewhat unusual-sounding concept of organizational effectiveness reflects some of the complications. Referring simply to organizational success bears less of an implication that the activities of the organization brought about the success. Referring to effectiveness suggests not only that the organization had good results but also that it brought about these results through its own management, design, and other features.

Many other terms for performing well also have limitations. In assessing business firms, most investors look carefully at their profitability. Yet sophisticated investors realize that short-term profitability may in some cases mask long-term problems. In addition, consumer advocates and environmental groups object to assessments of business performance that disregard concerns for the environment and ethical concerns for the consumer. In addition, profitability does not apply to government and nonprofit organizations. As with the generic approach in general, researchers have to consider the need for a general body of knowledge on organizational effectiveness that is not restricted to certain sectors or industries. As described shortly, in response to such complications, researchers have attempted a number of different approaches to organizational goals and effectiveness.

General Organizational Goals

An organizational goal is a condition that an organization seeks to attain. The discussion here recites many problems with the concept of goals, but organization theorists have developed some useful insights and distinctions about them. For example, the mission statements that have become so popular in recent decades represent what organization theorists would call official goals (Perrow, 1961). Official goals are formal expressions of general goals that present an organization’s major values and purposes, such as those for the SSA described earlier. One tends to encounter official goals in mission statements and annual reports, where they are meant to enhance the organization’s legitimacy and to motivate and guide its members. Operative goals are the relatively specific immediate ends an organization seeks, reflected in its actual operations and procedures. People in organizations often consider goals important as expressions of guiding organizational values that can stimulate and generally orient employees to the organization’s mission. In addition, clarifying goals for individuals and work groups can improve efficiency and productivity. The discussion of motivation in Chapter Ten reviews the research that shows that providing workers with clear, challenging goals can enhance their productivity. Nevertheless, the concept of a goal has many complications, with important implications for organizing and managing and for the debate over whether public and private organizations differ.

These complications include the problem that goals are always multiple (Rainey, 1993). A goal is always one of a set of goals that one is trying to achieve (Simon, 1973). The goals in a set often conflict with one another—maximizing one goal takes away from another goal. Short-term and long-term goals can conflict with each other. For example, although business firms supposedly have clearer, more measurable goals than public and nonprofit organizations, such firms have to try to manage conflicts among goals for short-term and long-term profits, community and public relations, employee and management development, and social responsibility (such as compliance with affirmative action and environmental protection laws). Goals are arranged in chains and hierarchies, and this makes it hard to express a goal in an ultimate or conclusive way. One goal leads to another or is an operative goal for a higher or more general goal. Many of the concepts related to organizational purpose—such as goals, objectives, values, incentives, and motives—overlap in various ways, leaving us with no conclusive or definitive terminology. Distinctions among these concepts are relatively arbitrary.

These complications appear to be related to a divergence among organization theorists, between those who take the concept of goals very seriously and those who reject it as relatively useless (Rainey, 1993). These complications present a problem for both theorists and practicing managers. The later discussion of models of effectiveness points out that these sorts of complications impede the assessment of organizational effectiveness—it can be difficult to say what an organization’s goals really are and to measure their achievement. It is important for leaders and managers to help the organization clarify its goals, but these complications make that a very challenging process. The next chapter discusses some of the procedures that members of organizations can use to clarify the organization’s goal statements.

Goals of Public Organizations

The complications surrounding the concept of goals also contribute to an interesting anomaly in the debate over the distinctiveness of public organizations. They imply that all organizations, including business firms, have vague, multiple, and relatively intangible goals. Without a doubt, however, the most often repeated observations about public organizations are that their goals are particularly vague and intangible compared to those of private business firms and that they more often have multiple, conflicting goals (see III.1.a in Exhibit 3.1; Rainey, 1993). Previous chapters illustrated the meaning of this observation. Public organizations produce goods and services that are not exchanged in markets. Government auspices and oversight imposed on these organizations include such multiple, conflicting, and often intangible goals as the constitutional, competence, and responsiveness values discussed in Chapters Four and Five (see Exhibit 4.3). In addition, authorizing legislation often assigns vague missions to government agencies and provides vague guidance for public programs (Lowi, 1979; Seidman and Gilmour, 1986). Given such mandates, coupled with concerns over public opinion and public demands, agency managers feel pressured to balance conflicting, idealized goals. Conservation agencies, for example, receive mandates and pressures both to conserve natural resources and to develop them (Wildavsky, 1979, p. 215). Prison commissioners face pressures both to punish offenders and to rehabilitate them (DiIulio, 1990). Police chiefs must try to find a balance between keeping the peace, enforcing the law, controlling crime, preventing crime, ensuring fairness and respect for citizen rights, and operating efficiently and with minimal costs (Moore, 1990).

In addition, many observers go on to assert that these goal complexities have major implications for public organizations and their management. Some researchers emphasize the effect of these complexities on work attitudes and performance. Buchanan (1974, 1975) found that federal agency managers reported lower organizational commitment, job involvement, and work satisfaction than did managers in private business. He also found that the federal managers reported a weaker sense of having impacts on their organizations and a weaker sense of finding challenge in their jobs. He concluded that the vagueness and value conflicts inherent in public organizations’ goals were among several reasons the federal managers reported lower commitment, involvement, and satisfaction. He argued that the diffuseness of agencies’ objectives made it harder to design challenging jobs for the public sector managers and harder for them to perceive the impact of their work, which in turn weakened federal managers’ commitment and satisfaction. Other studies have found more positive attitudes among managers in government than Buchanan observed, but his conclusions suggest the kinds of problems that vague and conflicting organizational goals may cause.

Boyatzis (1982), in a study of the competencies of a broad sample of managers, found that public managers displayed weaker “goal and action” competencies—those concerned with formulating and emphasizing means and ends. He concluded that the difference must result from the absence in the public sector of clear goals and performance measures such as sales and profits.

Other observations concern effects on organizational structure (pervasiveness of rules, number of levels) and hierarchical delegation. Some scholars have asserted that the goal ambiguity in public agencies and the consequent difficulties in developing clear and readily measurable performance indicators lead to performance evaluation on the basis of adherence to proper procedure and compliance with rules (Barton, 1980; Dahl and Lindblom, 1953; Lynn, 1981; Meyer, 1979; Warwick, 1975). Under accountability pressures and scrutiny by legislative bodies, the chief executive, oversight agencies, courts, and the media, higher-level executives in public agencies demand compliance with rules and procedures mandated by Congress or oversight agencies or contained in their chartering legislation. Executives and managers in public agencies also tend to add even more rules and clearance requirements in addition to externally imposed rules and procedures; plus, they add more hierarchical levels of review and generally resist delegation in an effort to control the units and individuals below them. The absence of clear, measurable, well-accepted performance criteria thus induces a vicious cycle of “inevitable bureaucracy” (Lynn, 1981) in which the demand for increased accountability increases the emphasis on rule adherence and hierarchical control. Some authors add the observation that these conditions breed a paradox in which the proliferation of rules and clearance requirements fails to achieve control over lower levels (Buchanan, 1975; Warwick, 1975). Rules provide some protections for people at lower levels, through civil service protections and the safety of strict compliance with other administrative rules. Superiors’ efforts to control lower-level employees through additional rules and reporting requirements add to bureaucratic complexity without achieving control.

In this way, goal ambiguity also supposedly contributes to a weakening of the authority of top leaders in public organizations. Because they cannot assess performance on the basis of relatively clear measures, their control over lower levels is weakened. The absence of clear performance measures also allegedly contributes to a weakening of leaders’ attentiveness to developing their agencies. Because they cannot simply refer to their performance against unambiguous targets to justify continued funding, they must play more political, expository roles to develop political support for their programs. Blumenthal (1983), reflecting on his experiences as a top federal and business executive, began his account of the differences between these roles with the observation that there is no bottom line in government. Media relations, general appearance and reputation, and political relations external to the agency figure more importantly in how others assess an executive’s performance than do concrete indicators of the performance of his or her agency. Allison (1983) provided an account of the similar observations of experienced public officials about the absence of a bottom line and of accepted and readily measurable performance indicators in public agencies.

Later chapters examine some of the research findings that support—or fail to support—these observations. For example, several surveys covering different levels of government, different parts of the United States, and different organizations asked managers in government agencies and business firms to respond to questions about whether the goals of their organization are vague, hard to define, and hard to measure. The results showed no particular differences between the government managers and the business managers in their responses to such questions (Rainey, 1983; Rainey, Pandey, and Bozeman, 1995). In addition, Bozeman and Rainey (1998) reported evidence that government managers in their study were more likely than business managers to say that their organizations had too many rules; this is not consistent with the claim that government managers like to create more and more rules and red tape. In spite of conflicting assertions and findings such as these, the main point is that many observers claim that the goals of public organizations have a distinct character that influences their other characteristics and their management. The findings just mentioned do not necessarily prove that there are no such differences, but they certainly complicate the debate. They illustrate the importance for researchers and managers of clarifying just what is meant by these repeated references to the vague, conflicting, multiple goals of public agencies and of proving or disproving their alleged effect on organizations and management in government.

Regardless of these complications in the analysis of the goals of public agencies, it is still very important and useful for agency leaders and managers to try to clarify their organization’s goals and assess its effectiveness in achieving them. Both the Web sites of many public agencies and the following chapter provide many examples of efforts at clarifying goals and missions, and an expanding literature on public management provides many more (Behn, 1994, p. 50; Denhardt, 2000; Hargrove and Glidewell, 1990, p. 95; Meyers, Riccucci, and Lurie, 2001). Chapter Nine describes a stream of research in psychology that has found that work groups perform better when given clear, challenging goals (Locke and Latham, 1990a; Wright, 2001, 2004). In seeking to clarify goals, however, managers need to be aware of the attendant complications and conflicts. They also need to be aware of the concepts and models for assessing organizational effectiveness that researchers have developed, as well as of the controversies over the strengths and weaknesses of the models and the trade-offs among them.

Models for Assessing Organizational Effectiveness

The people who study organizational effectiveness agree on many of the preceding points, but they have never come to agreement on one conclusive model or framework for assessing effectiveness (Daft, 2013; Hall and Tolbert, 2004). The complexities just described, as well as numerous others, have caused them to try many approaches.

The Goal Approach

When organization theorists first began to develop models of organizational effectiveness, it appeared obvious that one should determine the goals of one’s organization and assess whether it achieves them. As suggested already, however, organizations have many goals, which vary along many dimensions and often conflict with one another. Herbert Simon (1973) once pointed out that a goal is always embedded in a set of goals, which a person or group tries to maximize simultaneously—such as to achieve excellence in delivery of services to clients but also keep the maintenance schedule up, keep the members happy and motivated, maintain satisfactory relations with legislators and interest groups, and so on. Many different coalitions or stakeholders associated with an organization—managers, workers, client and constituency groups, oversight and regulatory agencies, legislators, courts, people in different subunits with different priorities for the organization, and so on—can have different goals for the organization.

One can also state goals at different levels of generality, in various terms, and in various time frames (short term versus long term). Goals always link together in chains of means and ends, in which an immediate objective can be expressed as a goal but ultimately serves as a means to a more general or longer-term goal. In addition, researchers and consultants can have a hard time specifying an organization’s goals because the people in the organization have difficulty stating or admitting the real goals. Organizations have not only formal, publicly espoused goals but also actual goals. In their annual reports, public agencies and business firms often make glowing statements of their commitment to the general welfare as well as to their customers and clients. An automobile company might express commitment to providing the American people with the safest, most enjoyable, most efficient automobiles in the world. A transportation agency might state its determination to serve all the people of its state with the safest, most efficient, most effective transportation facilities and processes possible. Yet the actual behavior of these organizations may indicate more concern with their economic security than with their clients and the general public. The goal model, in simplified forms, implies a view of management as a rational, orderly process. Earlier chapters have described how management scholars increasingly depict managerial decisions and contexts as more turbulent, intuitive, paradoxical, and emergent than a rational, goal-based approach implies.

All of these complications cause organizational effectiveness researchers to search for alternatives to a simple goal model. As the discussion of strategy in Chapter Four demonstrated, however, experts still exhort managers to identify missions, core values, and strategies. This may depart from a strict goal-based approach, but when you tell people to decide what they want to accomplish and to design strategies to achieve those conditions, you are talking about goals, even if you devise some other names for them. Goal clarification also plays a key role in managerial procedures described in later chapters, such as management by objectives (MBO).

Experts have suggested various terminologies and procedures for identifying organizational goals, and the goal model has never really been banished from the search for effectiveness criteria. These prescriptive frameworks, however, illustrate many of the complexities of goals mentioned earlier. Morrisey (1976), for example, illustrated the multiple levels and means-ends relationships of goals. He suggested a framework for public managers to use in developing MBO programs that he describes as a funnel in which the organization moves from greater generality to greater specificity by stating goals and missions, key results areas, indicators, objectives, and finally, action plans. Gross (1976) suggested a framework involving seven different groups of goals—satisfying interests (such as those of clients and members), producing output, making efficient use of inputs, investing in the organization, acquiring resources, observing codes (such as laws and budgetary guidelines), and behaving rationally (through research and proper administration). Under each of these general goals he listed multiple subgoals. Obviously, managers and researchers have difficulty clearly and conclusively specifying an organization’s goals.

For similar reasons, researchers have grappled with complications in measuring effectiveness. As usual, they have encountered the problem of choosing between subjective measures and objective measures. Some have asked respondents to rate the effectiveness of organizations, sometimes asking members for the ratings, sometimes comparing members’ ratings of their own units in the organization with the ratings provided by other members (such as top managers or members of other units). Sometimes they have asked people outside the organization for ratings. Others have developed more objective measures, such as profitability and productivity indicators, from records or other sources. Some researchers have developed both types of evidence, but they have found this expensive. They have also sometimes found that the two types of measures may not correlate with each other. In one frequently used variant of the goals approach, researchers have not sought to determine the specific goals of a specific organization; rather, they have measured ratings of effectiveness on certain criteria or goals that they assume all organizations must pursue, such as productivity, efficiency, flexibility, and adaptability. Mott (1972), for example, studied the effectiveness of government organizations (units of NASA; the State Department; the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; and a state mental hospital) by asking managers in them to rate the quantity, quality, efficiency, adaptability, and flexibility of their divisions.

The Systems-Resource Approach

Partly because of difficulties with goal models, Yuchtman and Seashore (1967) developed a systems-resource model. They concentrated on whether an organization can attain valued resources from its environment to sustain itself. They placed effectiveness criteria in a hierarchy, with the organization’s ability to exploit external resources and opportunities as the ultimate criterion. They regarded this criterion as being ultimately immeasurable by itself: it has to be inferred by measuring the next-highest, or penultimate, criteria, which they identified in a study of insurance companies. These criteria included such factors as business volume, market penetration, youthfulness of organizational members, and production and maintenance costs. They developed these factors by using statistical techniques to group together measures of organizational activities and characteristics such as sales and number of policies in force. Drawing on a survey they conducted in the same companies, they also examined the relationships between lower-order, subsidiary variables, such as communication and managerial supportiveness, and the penultimate factors.

Not many researchers have followed this lead with subsequent research efforts. Critics have raised questions about whether the approach confuses the conception and ordering of important variables. Some of the penultimate factors could just as well be called goals, others seem to represent means for achieving goals, and some of the factors seem more important than others. Critics have complained that the analytical techniques bunched together unlike factors inappropriately. Others have pointed out that the criteria represent the interests of those in charge of the organizations, even though other actors, such as customers and public interest groups, might have very different interests.

Still, insights from the study influenced later developments in thinking about effectiveness. The study found that some subsidiary variables were related to later readings on penultimate variables. This shows that effective procedures now can lead to effective outcomes later and emphasizes the importance of examining such relationships over time. Some subsidiary measures are linked strongly to certain penultimate factors but not to others. This shows that one can point to different dimensions of effectiveness, with different sets of variables linking with them.

Also, while few researchers have reported additional studies following this model, at least one such study applied it to public agencies. Molnar and Rogers (1976) analyzed county-level offices of 110 public agencies, including various agricultural, welfare, community development, conservation, employment, and planning and zoning agencies. They argued that the resource-dependence model, which is applied to business firms, needs modification for public agencies, for reasons similar to those discussed earlier in this book—absence of profit and of sales in markets, which blurs the link between inputs and outputs; consequent evaluation by political officials and other political actors; and an emphasis on meeting community or social needs that rivals emphases on internal efficiency.

Rogers and Molnar had people in the agencies rate their own organization’s effectiveness and the effectiveness of other organizations in the study. To represent the systems-resource approach for public agencies, they examined how many resources (equipment, funds, personnel, meeting rooms) an agency provided to other agencies in the study (“resource outflow”) and how many they received from other agencies (“resource inflow”). They also calculated a score for how much resources flowing in exceeded resources flowing out. They found that the higher the level of resources flowing into an agency, the higher the level of resources flowing out. The more effective agencies thus appeared better able to develop effective exchanges with other agencies, using their own resources to attract resources. Of course, the effectiveness of public agencies involves many additional dimensions, but this study offers an interesting analysis of one means of examining it.

Participant-Satisfaction Models

Another approach involves asking participants about their satisfaction with the organization. This approach focuses on whether the members of an organization feel that it fulfills their needs or that they share its goals and work to achieve them. This approach can figure importantly in managing an organization, but it has serious limitations if participation is conceived too narrowly. Participants include not just employees but also suppliers, customers, regulators and external controllers, and allies. Some of the more recent studies of effectiveness ask many different participants from such categories for ratings of an organization (Cameron, 1978). Others have tried to build in more ethical and social-justice considerations by examining how well an organization serves or harms the most disadvantaged participants (Keeley, 1984). The participant-satisfaction approach thus adds crucial insights to our thinking about effectiveness, but even these elaborated versions of the approach encounter problems in handling the general social significance of an organization’s performance. Organizations also affect the interests of the general public or society and of individuals not even remotely associated with the organization as participants.

Human Resource and Internal Process Models

Internal process approaches to organizational effectiveness assess it by referring to such factors as internal communications, leadership style, motivation, interpersonal trust, and other internal states assumed to be desirable. Likert (1967) developed a four-system typology that follows this pattern, assuming that as one enhances open and employee-centered leadership, communication, and control processes, one achieves organizational effectiveness. Blake and Mouton’s managerial grid (1984) involves similar assumptions, as do many organization development approaches.

Some who take positions quite at odds with the human relations orientation nevertheless share this general view. Management systems experts who concentrate on whether an organization’s accounting and control systems work well make similar assumptions. These orientations have played an important role in the debate over what public management involves. Some writers see inadequacies in public management primarily because of weak management systems and procedures of the sort that purportedly exist in superior form in industry (Crane and Jones, 1982; U.S. General Accounting Office, 2003). They call for better accounting and control systems, better inventory controls, better purchasing and procurement, and better contracting procedures. These human resource and internal process approaches do not involve complete conceptions of organizational effectiveness, but public managers often employ them, and experts assessing public organizations apply them.

The Government Performance Project

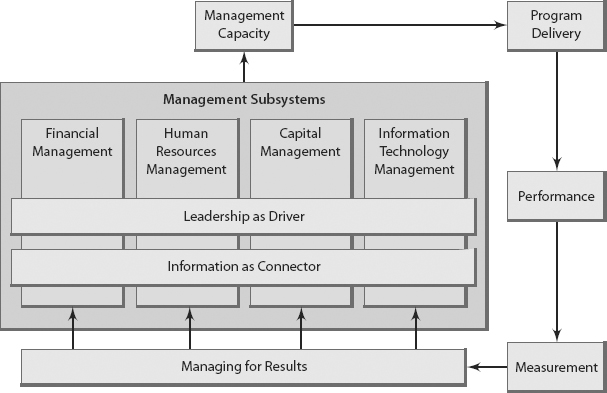

An example of an internal process application, and one of the most elaborate initiatives in assessing effectiveness of governments and government agencies, the Government Performance Project (GPP) received considerable professional and public attention at the turn of the twenty-first century. It involved one of the most widely applied efforts—if not the most widely applied effort—ever undertaken to assess effectiveness of government entities. In 1996, supported by a grant from the Pew Charitable Trusts, researchers at the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at Syracuse University, in partnership with representatives of Governing magazine, developed a process for rating the management capacity of local and state governments and federal agencies in the United States. In spite of its name, the GPP does not measure performance directly, but rather evaluates the capacity of management systems in government entities and thus represents a variant of an internal process model. The GPP evaluates five management system areas: financial management, human resources management, capital management, information technology management, and managing for results. The assessments also seek to determine how well these management systems are integrated in a government or government agency. Figure 6.1 illustrates this basic framework.

FIGURE 6.1. CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK OF THE GOVERNMENT PERFORMANCE PROJECT

As Figure 6.1 implies, the assessment procedure is based on the assumption that governments and government organizations perform well when they have strong management capacity in the areas indicated in the figure. The framework provides general criteria for each of the five management areas. Panels of experts helped to choose measures and indicators for these criteria. For example, criteria for financial management include a multiyear perspective on budgeting; mechanisms that preserve fiscal health; sufficient availability of financial information to policymakers, managers, and citizens; and appropriate control over financial operations. Human resources management criteria include provisions for strategic analysis of human resource needs, ability to obtain needed employees and a skilled workforce, and ability to motivate employees. Information technology (IT) management includes such criteria as whether IT systems support managers’ information needs and strategic goals, and support communication with citizens and service delivery to them, as well as the adequacy of planning, training for, procuring, and evaluating IT systems. Criteria for managing for results include engagement in results-oriented strategic planning, use of results in policymaking and management, use of indicators to measure results, and communication of results to stakeholders.

The GPP assessed these capacities in federal agencies, state governments, and city and county governments, assigning letter grades (that is, A, B, C) for each of the five management capacities and for overall capacity. The procedures for assessing these capacities were not available to the public as of the end of 2002. The Web site describes the procedures as follows:

The GPP grades governments based on the analysis of information it collects from the following resources and procedures: criteria-based assessment, comprehensive self-report surveys, document and Web site analysis, extensive follow-up and validation, statistical checks and comparisons, journalistic interviews with managers and stakeholders, and journalist/academic consensus. Surveys are distributed in March, governments return completed surveys and submit documents by June, analysis occurs during July to November, grading takes place in November, and grades and results are released at the end of January.

Actually, both the academics and the journalists assigned grades to the government organizations, but their grades were similar. The academics assigned grades on the basis of analysis of the information gathered in the process just described, while the journalists relied more on interviews with the organizations. The researchers in charge of the project could not release the exact procedures for assessment because consulting firms were offering to work with government organizations on ways to get better grades, and the researchers felt that publication of the exact procedures could bias the process. The journalists relied on more subjective, journalistic methods.

In 1998, the project studied and rated management activities in fifty states and fifteen federal agencies. The state results were published in the February 1999 issue of Governing and the federal results were published in the February 1999 issue of Government Executive magazine. In 1999, the GPP assessed the management capacity of the top thirty-five U.S. cities by revenue and five federal agencies. The city results were published in the February 2000 issue of Governing and the federal results were published in the March 2000 issue of Government Executive. Furthermore, the release was covered by two national newspapers, the Christian Science Monitor and USA Today; more than 250 regional newspapers; and more than two hundred radio and television stations.

An interesting and ambitious project, the GPP nevertheless evades easy evaluation because one cannot review the actual assessment procedures. The assessments do not directly measure outcomes, impacts, or results for the organizations reviewed by the GPP, so as a version of an internal process model it does not directly address the actual effectiveness of government organizations in achieving goals and results.

Toward Diverse, Conflicting Criteria

Increasingly, researchers tried to examine multiple measures of effectiveness. Campbell (1977) and his colleagues, for example, reviewed various approaches to effectiveness, including those described earlier, and developed a comprehensive list of criteria (see Exhibit 6.1). Obviously, many dimensions figure into effectiveness. Even this elaborate list does not capture certain criteria, such as effectiveness in contributing to the general public interest or the general political economy.

As researchers try to incorporate more complex sets of criteria, it becomes evident that organizations pursue diverse goals and respond to diverse interests, which imposes trade-offs. Cameron (1978) reported a study of colleges and universities in which he gathered a variety of types of effectiveness measures. Reviewing the literature, he noted that effectiveness studies use many types of criteria, including organizational criteria such as goals, outputs, resource acquisition, and internal processes. They also vary in terms of their universality (whether they use the same criteria for all organizations or different ones for different organizations), whether they are normative or descriptive (describing what an organization should do or what it does do), and whether they are dynamic or static. He also noted different sources of criteria. One can refer to different constituencies, such as the dominant groups in an organization, many constituencies in and out of an organization, or mainly external constituents. The sources also vary by level, from the overall, external system to the organization as a unit, organizational subunits, and individuals. Finally, one can use organizational records or individuals’ perceptions as sources of criteria.

In his own study of educational institutions, Cameron (1978) drew on a variety of criteria: objective and perceptual criteria; measures reflecting the interests of students, faculty, and administrators; participant criteria; and organizational criteria (see Table 6.1). Cameron developed profiles of different educational institutions according to the nine general criteria and found them to be diverse. One institution scored high on student academic and personal development but quite low on student career development. Another had the opposite profile—low on the first two criteria, high on the third. One institution scored high on community involvement, the others scored relatively low. These variations show that even organizations in the same industry or service sector often follow different patterns of effectiveness. They may choose different strategies, involving somewhat different clients, approaches, and products or services. In addition, these differences show that effectiveness criteria can weigh against one another. By doing well on one criterion, an organization may show weaker performance on another. Cameron points out that a university aiming at distinction in faculty research may pay less attention to the personal development of undergraduates than a college more devoted to attracting and placing undergraduates.

TABLE 6.1. EFFECTIVENESS DIMENSIONS FOR EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS

Source: Adapted from Cameron, 1978, p. 630. See original table for numerous additional measures for each dimension.

| Perceptual Measures | Objective Measures |

| 1. Student educational satisfaction | |

| Student dissatisfaction | Number of terminations |

| Student complaints | Counseling center visits |

| 2. Student academic development | |

| Extra work and study | Percentage going on to graduate school |

| Amount of academic development | |

| 3. Student career development | |

| Number employed in field of major | Number receiving career counseling |

| Number of career-oriented courses | |

| 4. Student personal development | |

| Opportunities for personal development | Number of extracurricular activities |

| Emphasis on nonacademic development | Number in extramurals and intramurals |

| 5. Faculty and administrator employment satisfaction | |

| Faculty and administrators’ satisfaction with school and employment | Number of faculty members and administrators leaving |

| 6. Professional development and quality of the faculty | |

| Faculty publications, awards, conference | Percentage of faculty with doctorates |

| Number of new courses | |

| Teaching at the cutting edge | |

| 7. System openness and community interaction | |

| Employee community service | Number of continuing education courses |

| Emphasis on community relations | |

| 8. Ability to acquire resources | |

| National reputation of faculty | General funds raised |

| Drawing power for students | Previously tenured faculty hired |

| Drawing power for faculty | |

| 9. Organizational health | |

| Student-faculty relations | |

| Typical communication type | |

| Levels of trust | |

| Cooperative environment | |

| Use of talents and expertise |

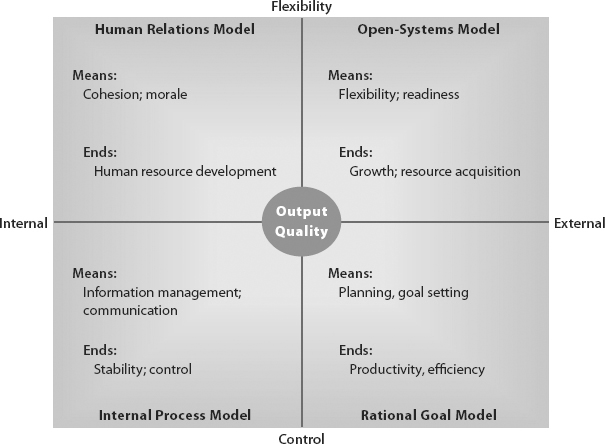

The Competing Values Approach

Quinn and Rohrbaugh (1983) drew the point about conflicting criteria into their competing values framework. They had panels of organizational researchers review the criteria in Table 6.1 to distill the basic dimensions out of the set. The panels’ responses indicated that the criteria grouped together along three value dimensions (see Figure 6.2). The first dimension, organizational focus, ranges from an internal emphasis on the well-being of the organization’s members to an external focus on the success of the entire organization. The second dimension is concerned with control as opposed to flexibility. The third involves relative concentration on means (such as good planning) or ends (such as achieving productivity goals). Quinn and Rohrbaugh pointed out that these dimensions reflect fundamental dilemmas that social scientists have debated for a long time—means versus ends, flexibility versus control and stability, internal versus external orientation.

FIGURE 6.2. THE COMPETING VALUES FRAMEWORK

Source: Quinn and Rohrbaugh, 1983. Reprinted by permission of the authors. Copyright ©1983, Institute of Management Sciences.

The dimensions combine to represent the four models of effectiveness shown in Figure 6.2. The human relations model emphasizes flexibility in internal processes and improving cohesion and morale as a means of developing the people in an organization. The internal process model also has an internal focus, but it emphasizes control—through maintaining sound information, auditing, and review systems—as a means to achieving stability. At the external end, the open-systems model emphasizes responsiveness to the environment, with flexibility in structure and process as a means to achieving growth and acquiring resources. The rational goal model emphasizes careful planning to maximize efficiency.

Quinn and Rohrbaugh recognized the contradictions between the different models and values. They argued, however, that a comprehensive model must retain all of these contradictions, because organizations constantly face such competition among values. Organizations have to stay open to external opportunities yet have sound internal controls. They must be ready to change but maintain reasonable stability. Effective organizations and managers balance conflicting values. They do not always do so in the same way, of course. Quinn and Cameron (1983) drew amoeba-like shapes on the diagram in Figure 6.2 to illustrate the different emphases that organizations place on the values. An organization that heavily emphasizes control and formalization would have a profile illustrated by a roughly circular shape that expands much more widely on the lower part of the diagram than on the upper part. For an organization that emphasizes innovation and informal teamwork, the circle would sweep more widely around the upper part of the chart, showing higher emphasis on morale and flexibility. This contrast again underscores the point that different organizations may pursue different conceptions of effectiveness.

Quinn and Cameron also pointed out that effectiveness profiles apparently shift as an organization moves through different stages in its life cycle. In addition, major constituencies can impose such shifts. They described how a unit of a state mental health agency moved from a teamwork-and-innovation profile to a control-oriented profile because of a series of newspaper articles criticizing the unit for lax rules, records, and rule adherence.

Still, the ultimate message is that organizations and managers must balance or concurrently manage competing values. Rohrbaugh (1981) illustrated the use of all the values with a measure of the effectiveness of an employment services agency. Quinn (1988) developed scales for managers to conduct self-assessments of their own orientation within the set of values, for use in training them to manage these conflicts. The competing values framework expresses the values in a highly generalized form and does not address the more specific, substantive goals of particular agencies or the explicit political and institutional values imposed on public organizations. Nevertheless, it provides valuable insights into the effectiveness of public organizations, especially on the point that the criteria are multiple, shifting, and conflicting.

The Balanced Scorecard

An approach to assessing organizational performance and effectiveness that has achieved considerable prominence incorporates multiple dimensions and measures into the process. Kaplan and Norton (1996, 2000) developed the Balanced Scorecard to prevent a narrow concentration on financial measures in business auditing and control systems. Devised for use by business firms, this model has been used by government organizations in innovative ways.

The Balanced Scorecard requires an organization to develop goals, measures, and initiatives for four perspectives (Kaplan and Norton, 1996, p. 44):

- The financial perspective, in which typical measures include return on investment and economic value added

- The customer perspective, involving such measures as customer satisfaction and retention

- The internal perspective, involving measures of quality, response time, cost, and new product introductions

- The learning and growth perspective, in which goals and measures focus on such matters as employee satisfaction and information system availability

Responding to the National Performance Review’s emphasis on setting goals and managing for results, a task force applied the Balanced Scorecard in developing a model for assessment of the federal government procurement system carried out in major federal agencies (Kaplan and Norton, 1996, pp. 181–182). Interestingly, Kaplan and Norton also described applications in the public sector that were in effect before descriptions of their model were published. Sunnyvale, California, a city repeatedly recognized for its excellence in management, had for more than twenty years produced annual performance reports stating goals and performance indicators for each major policy area. Charlotte, North Carolina, issued an objectives scorecard in 1995 reporting on accomplishments in “focus areas,” including community safety, economic development, and transportation. The report also provided performance measures from four perspectives, including the financial, customer service, internal work efficiency, and learning and growth perspectives (Kaplan and Norton, 1996, pp. 181–185). The Texas State Office of the Auditor developed its own version of the approach, adding a focus on mission for their public sector context, because financial results in public institutions do not play the central role they do in private firms. Their model includes concentrations on mission, customer focus, internal processes, learning and knowledge, and financial matters (Kerr, 2001).

Other agencies, influenced by the approach, have developed their own versions. In the major reforms at the Internal Revenue Service described in Chapters Eight and Twelve, the agency adopted a “balanced measures” approach. The model includes goals and measures in the areas of business process results, customer satisfaction, and employee satisfaction. The executives leading the reforms regularly reviewed reports from consulting firms that had conducted customer satisfaction and employee satisfaction surveys.

The Balanced Scorecard and related approaches raise plenty of issues that can be debated. For example, an emphasis on serving “customers” has grown in the field of public administration over the past decade. This trend has sparked some debate and controversy over whether government employees should think of citizens and clients as customers. In addition, the long-term success of balanced measurement systems remains to be seen. As indicated previously, some of the related approaches involve simply trying to measure employee satisfaction, and some measures of work satisfaction do not really assess learning and growth in the organization as Kaplan and Norton proposed. The Balanced Scorecard and similar balanced measurement approaches do, however, emphasize the important and valuable point that people in public organizations need to develop well-rounded and balanced measures of effectiveness that combine attention to results and impacts, internal capacity and development, and the perspectives of external stakeholders, including so-called customers.

Effectiveness in Organizational Networks

Government programs and policies have always involved complex clusters of individuals, groups, and organizations, but such patterns of networking have become even more prevalent in recent decades (Henry, 2002; Kettl, 2002; Raab, 2002; Vigoda, 2002). A variety of developments have fueled this trend, including increased privatization and contracting out of public services, greater involvement of the nonprofit sector in public service delivery, and complex problems that exceed the capacity of any one organization, as well as other trends (O’Toole, 1997). The growing significance of networks raises challenges for research, theory, and practice in public administration, especially in relation to the effectiveness of public organizations and public management. O’Toole (1997, p. 44) defined networks as “structures of interdependence involving multiple organizations or parts thereof, where one unit is not merely the formal subordinate of the others in some larger hierarchical arrangement.” Such situations do not involve typical or traditional chains of command and hierarchical authority. For managers, the lines of accountability and authority are loosened, and the management of a network requires more reliance on trust and collaboration than programs operated within the hierarchy of one organization (O’Toole, 1997). Managers also face varying degrees of responsibility to activate, mobilize, and synthesize networks (McGuire, 2002).

In addition to altering the roles of managers, networks bring up new questions about assessing effectiveness and achieving it, and researchers have developed new and important insights about such matters. For example, Provan and Milward (1995) analyzed the mental health services of four urban areas in the United States. They found that these services were provided by networks of different organizations, each of which provided some type of service or part of the package of mental health services available in the area. Quite significantly, virtually none of the organizations was a government organization. The government—the federal government for the most part—provided most of the funding for the mental health services in these areas, but networks of private and nonprofit organizations provided the services.

The researchers pointed out that for such networks of organizations, a real measure of effectiveness should not be focused on any individual organization. Instead, one must think in terms of the effectiveness of the entire network. Provan and Milward focused on clients in measuring the network’s effectiveness, using responses from clients, their families, and caseworkers concerning the clients’ quality of life, their satisfaction with the services of the network, and their level of functioning. They then examined the characteristics of the network in relation to these measures of effectiveness. They found that the most effective of the four mental health service networks was centralized and concentrated around a primary organization. The government funds for the system went directly to that agency, which played a strong central role in coordinating the other organizations in delivering services. This finding runs counter to the organic-mechanistic distinction discussed in earlier chapters, which suggests that decentralized, highly flexible arrangements are most appropriate (Provan and Milward, 1995, pp. 25–26).

More recently, Milward and Provan (1998, 2000) developed the findings of their study into principles about the governance of networks. They concluded that a network will most likely be effective when a powerful core agency integrates the network, the mechanisms for fiscal control by the state are direct and not fragmented, resources are plentiful, and the network is stable. In addition, they have further developed ideas about how one must evaluate networks, pointing out that assessing the effectiveness of networks requires evaluation on multiple levels. Evaluators must assess the effectiveness of the network at the community level, at the level of the network itself, and at the level of the organization participating in the network. Given the continuing and growing importance of networks, we can expect continuing emphasis on developing concepts and frameworks such as these.

Managing Goals and Effectiveness

One purpose of reviewing this material on goals and effectiveness relatively early in the book, before the chapters that follow, is to raise basic issues concerning the goals of public organizations that allegedly influence their operations and characteristics. In addition, the concepts and models of effectiveness provide a context and basic theme for the topics to be discussed. The complications with these concepts and the absence of a conclusive model of effectiveness raise challenges for researchers and practicing managers alike. The next chapter and later chapters show how important these challenges are, however, and provide examples of how leaders have addressed them. Later chapters provide examples of mission statements and expressions of goals and values that members of public organizations have developed. The next chapter discusses strategic management, decision making, and power relationships that are part of the process of developing and pursuing goals and effectiveness. Later chapters discuss topics such as organizational culture and leadership, communication, motivation, organizational change, and managing for excellence—all topics that relate to goals and effectiveness. As Figures 1.1 and 1.2 in Chapter One indicate, a central challenge for people in public organizations is the coordination of such issues and topics in pursuit of goals and effectiveness.

Effectiveness of Public Organizations

As noted at the outset of this book and this chapter, beliefs about the effectiveness of public organizations, and about their performance in comparison to business firms, are important parts of the culture of the United States and other countries. These beliefs and perceptions have influenced some of the major political developments in recent decades, and one could argue that they have helped shape the history of the United States and other nations. The preceding sections show, however, that assessing the effectiveness of organizations involves many complexities. Assessing the performance of the complex populations of organizations is even more complicated.

Chapter Fourteen returns to the topics of the effectiveness of public organizations and their effectiveness compared to private organizations. It argues that public organizations often operate very well, if not much better than suggested by the widespread public beliefs about their inferior performance indicated in public opinion polls. Chapter Fourteen makes this argument before covering additional ideas about the effective leadership and management of public organizations, claiming that public managers and leaders often perform well in managing goals and effectiveness.

- Key terms

- Discussion questions

- Topics for writing assignments or reports

- Class Exercise 1: The Nature of Public Service: The Connecticut Department of Transportation