CHAPTER ONE

THE CHALLENGE OF EFFECTIVE PUBLIC ORGANIZATION AND MANAGEMENT

As this book heads for publication, the president of the United States and his political opponents in Congress have entered into a dispute over sequestration of federal funds. Previous legislation required that funding for federal programs be sequestered, or withheld, if by a certain date the president and Congress could not agree on cuts in federal funding to reduce the federal deficit. The date passed and the sequestration began. Executives and managers in U.S. federal agencies had to decide how to make the funding reductions. They announced plans to reduce numerous federal programs and to reduce the services those programs delivered. These reductions would have serious adverse effects on government services at the state and local levels. Leaders of federal agencies announced plans to furlough tens of thousands of federal employees. An agreement between the president and Congress was still possible, rendering it unclear whether or not these furloughs and service reductions would actually take place. By the time readers devote attention to this book, they will know the outcomes of this sequestration episode. Whatever the outcomes, the situation illustrates an important characteristic of public or governmental organizations and the people in them. They are very heavily influenced by developments in the political and governmental context in which they operate. Even government employees who may never encounter an elected official in their day-to-day activities have their working lives influenced by the political system under whose auspices they operate.

During the same period of time, the news media and professional publications provided generally similar examples each day. A major storm caused immense damage in northeastern states. Soon after, stories in the news media described sharp criticisms of the public works department of a major city. Critics castigated the department’s management and leadership, alleging that weak management had led to an inadequate response to the storm that had aggravated the damage from it. In still another example, a major newspaper carried a front-page story claiming that excessive bureaucracy and poor management were causing inadequate and delayed services for veterans and their beneficiaries. Again and again, such reports illustrated similar points. Government organizations, which this book will usually call public organizations, deliver important services and discharge functions that many citizens consider crucial. Inadequate organization and management of those functions and services creates problems for citizens, from small irritations to severe and life-threatening damages. The organizations and the people in them have to carry out their services and functions under the auspices and influence of other governmental authorities. Hence they operate directly or indirectly in what David Aberbach and Bert Rockman call “the web of politics” (Aberbach and Rockman, 2000). The examples generally apply as well to governments in the other nations and the organizations within those governments. Nations around the world have followed a continuing pattern of organizing, reorganizing, reforming, and striving to improve government agencies’ management and performance (Kettl, 2002, 2009; Kickert, 2007, 2008; Light, 1997, 2008; Pollitt and Bouckaert, 2011). As in the United States, governmental or public organizations in all nations operate within a context of constitutional provisions, laws, and political authorities and processes that heavily influence their organization and management.

Toward Improved Understanding and Management of Public Organizations

All nations face decisions about the roles of their government and private institutions in their society. The pattern of reorganization and reform mentioned in the preceding section spawned a movement in many countries either to curtail government authority and replace it with greater private activity or to make government operations more like those of private business firms (Christensen and Laegreid, 2007; Pollitt and Bouckeart, 2011). This skepticism about government implies that there are sharp differences between government and privately managed organizations. During this same period, however, numerous writers argued that we had too little sound analysis of such differences and too little attention to management in the public sector. A large body of scholarship in political science and economics that focused on government bureaucracy had too little to say about managing that bureaucracy. This critique elicited a wave of research and writing on public management and public organization theory, in which experts and researchers have been working to provide more careful analyses of organizational and managerial issues in government.

This chapter elaborates on these points to develop another central theme of this book: we face a dilemma in combining our legitimate concerns about the performance of public organizations with the recognition that they play indispensable roles in society. We need to maintain and improve their effectiveness. We can profit by studying major topics from general management and organization theory and examining the rapidly increasing evidence of their successful application in the public sector. That evidence indicates that the governmental context strongly influences organization and management, sometimes constraining performance. Just as often, however, governmental organizations and managers perform much better than is commonly acknowledged. Examples of effective public management abound. These examples usually reflect the efforts of managers in government who combine managerial skill with effective knowledge of the public sector context. Experts continue to research and debate the nature of this combination, however, as more evidence appears rapidly and in diverse places. This book seeks to base its analysis of public management and organizations on the most careful and current review of this evidence to date.

General Management and Public Management

This book proceeds on the argument that a review and explanation of the literature on organizations and their management, integrated with a review of the research on public organizations, supports understanding and improved management of public organizations. As this implies, these two bodies of research and thought are related but separate, and their integration imposes a major challenge for those interested in public management. The character of these fields and of their separation needs clarification. We can begin that process by noting that scholars in sociology, psychology, and business administration have developed an elaborate body of knowledge in the fields of organizational behavior and organization theory.

Organizational Behavior, Organization Theory, and Management

The study of organizational behavior had its primary origins in industrial and social psychology. Researchers of organizational behavior typically concentrate on individual and group behaviors in organizations, analyzing motivation, work satisfaction, leadership, work-group dynamics, and the attitudes and behaviors of the members of organizations. Organization theory, on the other hand, is based more in sociology. It focuses on topics that concern the organization as a whole, such as organizational environments, goals and effectiveness, strategy and decision making, change and innovation, and structure and design. Some writers treat organizational behavior as a subfield of organization theory. The distinction is primarily a matter of specialization among researchers; it is reflected in the relative emphasis each topic receives in specific textbooks (Daft, 2013; Schermerhorn, 2011) and in divisions of professional associations.

Organization theory and organizational behavior are covered in every reputable, accredited program of business administration, public administration, educational administration, or other form of administration, because they are considered relevant to management. The term management is used in widely diverse ways, and the study of this field includes the use of sources outside typical academic research, such as government reports, books on applied management, and observations of practicing managers about their work. While many elements play crucial roles in effective management—finance, information systems, inventory, purchasing, production processes, and others—this book concentrates on organizational behavior and theory. We can further define this concentration as the analysis and practice of such functions as leading, organizing, motivating, planning and strategy making, evaluating effectiveness, and communicating.

A strong tradition, hereafter called the “generic tradition,” pervades organization theory, organizational behavior, and general management. As discussed in Chapters Two and Three, most of the major figures in this field, both classical and contemporary, apply their theories and insights to all types of organizations. They have worked to build a general body of knowledge about organizations and management. Some pointedly reject any distinctions between public and private organizations as crude stereotypes. Many current texts on organization theory and management contain applications to public, private, and nonprofit organizations (for example, Daft, 2013).

In addition, management researchers and consultants frequently work with public organizations and use the same concepts and techniques they use with private businesses. They argue that their theories and frameworks apply to public organizations and managers since management and organization in government, nonprofit, and private business settings face similar challenges and follow generally similar patterns.

Public Administration, Economics, and Political Science

The generic tradition offers many valuable insights and concepts, as this book will illustrate repeatedly. Nevertheless, we do have a body of knowledge specific to public organizations and management. We have a huge government, and it entails an immense amount of managerial activity. City managers, for example, have become highly professionalized. We have a huge body of literature and knowledge about public administration. Economists have developed theories of public bureaucracy (Downs, 1967). Political scientists have written extensively about it (Meier and Bothe, 2007; Stillman, 2004). These political scientists and economists usually depict the public bureaucracy as quite different from private business. Political scientists concentrate on the political role of public organizations and their relationships with legislators, courts, chief executives, and interest groups. Economists analyzing the public bureaucracy emphasize the absence of economic markets for its outputs. They have usually concluded that this absence of markets makes public organizations more bureaucratic, inefficient, change-resistant, and susceptible to political influence than private firms (Barton, 1980; Breton and Wintrobe, 1982; Dahl and Lindblom, 1953; Downs, 1967; Niskanen, 1971; Tullock, 1965).

In the 1970s, authors began to point out the divergence between the generic management literature and that on the public bureaucracy and to call for better integration of these topics.1 These authors noted that organization theory and the organizational behavior literature offer elaborate models and concepts for analyzing organizational structure, change, decisions, strategy, environments, motivation, leadership, and other important topics. In addition, researchers had tested these frameworks in empirical research. Because of their generic approach, however, they paid too little attention to the issues raised by political scientists and economists concerning public organizations. For instance, they virtually ignored the internationally significant issue of whether government ownership and economic market exposure make a difference for management and organization.

Critics also faulted the writings in political science and public administration for too much anecdotal description and too little theory and systematic research (Perry and Kraemer, 1983; Pitt and Smith, 1981). Scholars in public administration generally disparaged as inadequate the research and theory in that field (Kraemer and Perry, 1989; McCurdy and Cleary, 1984; White and Adams, 1994). In a national survey of research projects on public management, Garson and Overman (1981, 1982) found relatively little funded research on general public management and concluded that the research that did exist was highly fragmented and diverse.

Neither the political science nor the economics literature on public bureaucracy paid as much attention to internal management—designing the structure of the organization, motivating and leading employees, developing internal communications and teamwork—as did the organization theory and general management literature. From the perspective of organization theory, many of the general observations of political scientists and economists about motivation, structure, and other aspects of the public bureaucracy appeared oversimplified.

Issues in Education and Research

Concerns about the way we educate people for public management also fueled the debate about the topic. In the wake of the upsurge in government activity during the 1960s, graduate programs in public administration spread among universities around the country. The National Association of Schools of Public Affairs and Administration began to accredit these programs. Among other criteria, this process required master of public administration (M.P.A.) programs to emphasize management skills and technical knowledge rather than to provide a modified master’s program in political science. This implied the importance of identifying how M.P.A. programs compare to master of business administration (M.B.A.) programs in preparing people for management positions. At the same time, it raised the question of how public management differs from business management.

These developments coincided with expressions of concern about the adequacy of our knowledge of public management. In 1979 the U.S. Office of Personnel Management (1980) organized a prestigious conference at the Brookings Institution. The conference featured statements by prominent academics and government officials about the need for research on public management. It sought to address a widespread concern among both practitioners and researchers about “the lack of depth of knowledge in this field” (p. 7). At around the same time, various authors produced a stream of articles and books arguing that public sector management involves relatively distinct issues and approaches. They also complained, however, that too little research and theory and too few case exercises directly addressed the practice of active, effective public management (Allison, 1983; Chase and Reveal, 1983; Lynn, 1981, 1987). More recently, this concern with building research and theory on public management has developed into something of a movement, as more researchers have converged on the topic. Beginning in 1990, a network of scholars have come together for a series of five National Public Management Research Conferences. These conferences have led to the publication of books containing research reported at the conferences (Bozeman, 1993; Brudney, O’Toole, and Rainey, 2000; Frederickson and Johnston, 1999; Kettl and Milward, 1996) and of many professional journal articles. In 2000, the group formed a professional association, the Public Management Research Association, to promote research on the topic. Later chapters will cover many of the products and results of their research.

Ineffective Public Management?

On a less positive note, recurrent complaints about inadequacies in the practice of public management have also fueled interest in the field, in an intellectual version of the ambivalence about public organizations and their management that the public and political officials tend to show. We generally recognize that large bureaucracies—especially government bureaucracies—have a pervasive influence on our lives. They often blunder, and they can harm and oppress people, both inside the organizations and without (Adams and Balfour, 2009). We face severe challenges in ensuring both their effective operation and our control over them through democratic processes. Some analysts contend that our efforts to maintain this balance of effective operation and democratic control often create disincentives and constraints that prevent many public administrators from assuming the managerial roles that managers in industry typically play (Gore, 1993; Lynn, 1981; National Academy of Public Administration, 1986; Warwick, 1975). Some of these authors argue that too many public managers fail to seriously engage the challenges of motivating their subordinates, effectively designing their organizations and work processes, and otherwise actively managing their responsibilities. Both elected and politically appointed officials face short terms in office, complex laws and rules that constrain the changes they can make, intense external political pressures, and sometimes their own amateurishness. Many concentrate on pressing public policy issues and, at their worst, exhibit political showmanship and pay little attention to the internal management of agencies and programs under their authority. Middle managers and career civil servants, constrained by central rules, have little authority or incentive to manage. Experts also complain that too often elected officials charged with overseeing public organizations show too little concern with effectively managing them. Elected officials have little political incentive to attend to “good government” issues, such as effective management of agencies. Some have little managerial background, and some tend to interpret managerial issues in ways that would be considered outmoded by management experts.

Effective Public Management

In contrast with criticisms of government agencies and employees, other authors contend that public bureaucracies perform better than is commonly acknowledged (Doig and Hargrove, 1987; Downs and Larkey, 1986; Goodsell, 2003, 2011; Milward and Rainey, 1983; Rainey and Steinbauer, 1999). Others described successful governmental innovations and policies (Borins, 2008; Holzer and Callahan, 1998). Wamsley and his colleagues (1990) called for increasing recognition that the administrative branches of governments in the United States play as essential and legitimate a role as the other branches of government. Many of these authors pointed to evidence of excellent performance by many government organizations and officials and the difficulty of proving that the private sector performs better.

In response to this concern about the need for better analysis about effective public management, the literature continued to burgeon in the 1990s and into the new century. As later chapters will show, a genre has developed that includes numerous books and articles about effective leadership, management, and organizational practices in government agencies.2 These contributions tend to assert that government organizations can and do perform well, and that we need continued inquiry into when they do, and why.

The Challenge of Sustained Attention and Analysis

The controversies described in the previous sections reflect fundamental complexities of the American political and economic systems. Those systems have always subjected the administrative branch of government to conflicting pressures over who should control and how, whose interests should be served, and what values should predominate (Waldo, [1947] 1984). Management involves paradoxes that require organizations and managers to balance conflicting objectives and priorities. Public management often involves particularly complex objectives and especially difficult conflicts among them.

In this debate over the performance of the public bureaucracy and whether the public sector represents a unique or a generic management context, both sides are correct, in a sense. General management and organizational concepts can have valuable applications in government; however, unique aspects of the government context must often be taken into account. In fact, the examples of effective public management given in later chapters show the need for both. Managers in public agencies can effectively apply generic management procedures, but they must also skillfully negotiate external political pressures and administrative constraints to create a context in which they can manage effectively. The real challenge involves identifying how much we know about this process and when, where, how, and why it applies. We need researchers, practitioners, officials, and citizens to devote sustained, serious attention to developing our knowledge of and support for effective public management and effective public organizations.

Organizations: A Definition and a Conceptual Framework

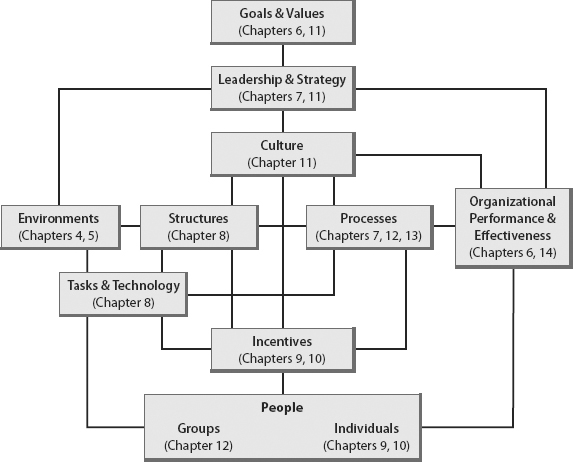

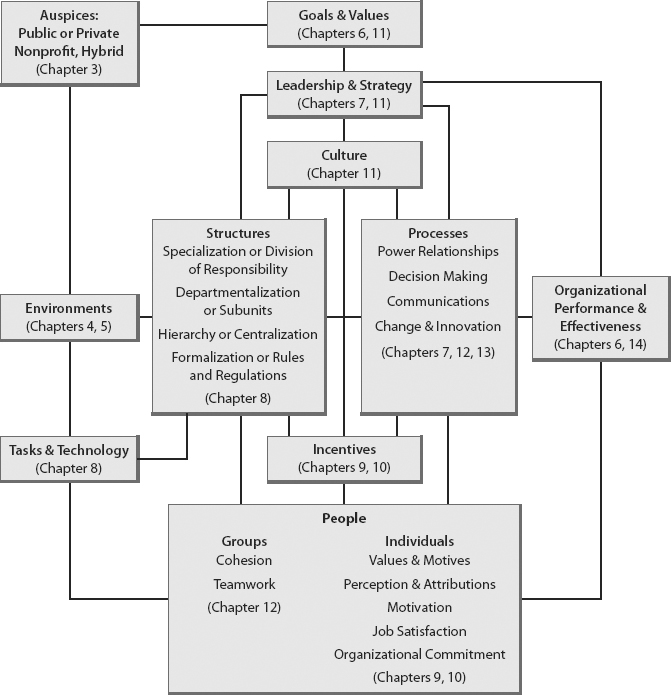

As we move toward a review and analysis of research relevant to public organizations and their management, it becomes useful to clarify the meaning of basic concepts about organizations and to develop a framework to guide the sustained analysis this book will provide. Figure 1.1 presents a framework for this purpose. Figure 1.2 elaborates on some of the basic components of this framework, providing more detail about organizational structures, processes, and people.

FIGURE 1.1. A FRAMEWORK FOR ORGANIZATIONAL ANALYSIS

FIGURE 1.2. A FRAMEWORK FOR ORGANIZATIONAL ANALYSIS (ELABORATION OF FIGURE 1.1)

Writers on organization theory and management have argued for a long time over how best to define organization, reaching little consensus. It is not a good use of time to worry over a precise definition, so here is a provisional one that employs elements of Figure 1.1. This statement goes on too long to serve as a precise definition; it actually amounts to more of a perspective on organizations:

An organization is a group of people who work together to pursue a goal. They do so by attaining resources from their environment. They seek to transform those resources by accomplishing tasks and applying technologies to achieve effective performance of their goals, thereby attaining additional resources. They deal with the many uncertainties and vagaries associated with these processes by organizing their activities. Organizing involves leadership processes, through which leaders guide the development of strategies for achieving goals and the establishment of structures and processes to support those strategies. Structures are the relatively stable, observable assignments and divisions of responsibility within the organization, achieved through such means as hierarchies of authority, rules and regulations, and specialization of individuals, groups, and subunits. The division of responsibility determined by the organizational structure divides the organization’s goals into components that the different groups and individuals can concentrate on—hence the term organization, referring to the set of organs that make up the whole. This division of responsibility requires that the individual activities and units be coordinated. Structures such as rules and regulations and hierarchies of authority can aid coordination. Processes are less physically observable, more dynamic activities that also play a major role in the response to this imperative for coordination. They include such activities as determining power relationships, decision making, evaluation, communication, conflict resolution, and change and innovation. Within these structures and processes, groups and individuals respond to incentives presented to them, making the contributions and producing the products and services that ultimately result in effective performance.

While this perspective on organizations and the framework depicted in the figures seem very general and uncontroversial, they have a number of serious implications that could be debated at length. Mainly, however, they simply set forth the topics that the chapters of this book cover and indicate their importance as components of an effective organization. Management consultants working with all types of organizations claim great value and great successes for frameworks about as general as this one, as ways of guiding decision makers through important topics and issues. Leaders, managers, and participants in organizations need to develop a sense of what it means to organize effectively, and of the most important aspects of an organization that they should think about in trying to improve the organization or to organize some part of it or some new undertaking. The framework offers one of many approaches to organizing one’s thinking about organizing, and the chapters to come elaborate its components.

After that, the final chapter provides an example of applying the framework to organizing for and managing a major trend, the contracting out of public services.

As this chapter has discussed, this book proceeds on certain assertions and assumptions. Government organizations perform crucial functions. We can improve public management and the performance of public agencies by learning about the literature on organization theory, organizational behavior, and general management and applying it to government agencies and activities.

The literature on organizations and management has not paid enough attention to distinctive characteristics of public sector organizations and managers. This book integrates research and thought on the public sector context with the more general organizational and management theories and research. This integration has important implications for the debates over whether public management is basically ineffective or often excellent and over how to reform and improve public management and education for people who pursue it. A sustained, careful analysis, drawing on available concepts, theories, and research and organized around the general framework presented here, can contribute usefully to advancing our knowledge of these topics.

- Key terms

- Discussion questions

- Topics for writing assignments or reports

Notes

1. Authors who address the divergence between the generic management literature and that on the public bureaucracy and who call for better integration of these topics include Allison, 1983; Bozeman, 1987; Hood and Dunsire, 1981; Lynn, 1981; Meyer, 1979; Perry and Kraemer, 1983; Pitt and Smith, 1981; Rainey, Backoff, and Levine, 1976; Wamsley and Zald, 1973; Warwick, 1975.

2. Books and articles about effective leadership, organization, and management in government include Barzelay, 1992; Behn, 1994; Borins, 2008; Cohen and Eimicke, 1998; Cooper and Wright, 1992; Denhardt, 2000; Doig and Hargrove, 1987; Hargrove and Glidewell, 1990; Holzer and Callahan, 1998; Ingraham, Thompson, and Sanders, 1998; Jones and Thompson, 1999; Light, 1998; Linden, 1994; Meier and O’Toole, 2006; Morse, Buss, and Kinghorn, 2007; Newell, Reeher, and Ronayne, 2012; Osborne and Gaebler, 1992; O’Toole and Meier, 2011; Popovich, 1998; Rainey and Steinbauer, 1999; Riccucci, 1995, 2005; Thompson and Jones, 1994; Wolf, 1997. Books that defend the value and performance of government in general include Esman, 2000; Glazer and Rothenberg, 2001; Neiman, 2000.