CHAPTER 5

Innovation Governance Models

In sophisticated innovation-driven companies, it may not be easy to define in simple terms precisely who “owns” or “governs” innovation because of the multiplicity of owners and actors. In addition the number, nature and roles of these governance mechanisms usually evolve naturally over time, as management reinforces or keeps enlarging the scope of their responsibilities. Innovative companies do not change their governance models overnight at the whim of a new CEO or CTO. They work on their models to perfect them and enhance their effectiveness. Good innovation governance builds upon experience and calls for consistency over time and constant improvements.

- The Group wishes to emphasize the need for dynamic and responsible innovation that can generate growth and sustainable improvements.

- The function of each member of the Group includes an innovation dimension with a significant weight. Personal evaluations, compensation and career evolution are linked, among other factors, to that criterion, which is applied at individual and team level.

- At all levels, Group management includes among its most important missions the development and encouragement of innovation in all its forms, including participative innovation. The Group recognizes and rewards innovators. It accepts that the approach presents risks.

- Quality ideas that fit within the Group's strategic priorities receive the means to demonstrate their validity and, if it is proven, to be deployed.

- Innovation integrates a number of external stakeholders, starting with customers.

Innovative Companies Deploy a Range of Governance Mechanisms

Solvay, one of the world's top 10 chemical groups, illustrates how companies deploy a range of innovation governance models and how these evolve over time to respond to new business demands. The example of Solvay may be inspiring for companies that are embarking on the complex process of building an organizational framework and allocating a range of responsibilities for innovation.

From its roots in long-established commodity products like sodium carbonate, Solvay has evolved to become a highly respected global supplier of advanced chemicals and plastics. This transformation reflects a strong management commitment to innovation.

With innovation as its key pillar, Solvay focused naturally on R&D and technology. However, in the late 1990s, top management broadened the scope of Solvay's innovation efforts with the objective of mobilizing staff in participative, or bottom-up, initiatives. It also formalized its innovation governance activities, first by appointing an executive committee member – the head of one of its large business sectors – as corporate innovation sponsor with the mission to stimulate, steer, and sustain innovation. Second, management brought in an experienced innovation practitioner as dedicated group innovation champion, with the mission to support all corporate innovation initiatives and orchestrate this bottom-up effort.

The first outcomes of this new management emphasis on bottom-up innovation included, among others, the creation and sharing of an innovation charter (see box); the organization of a structured idea management system; and the awarding of innovation trophies in six different categories of innovation, including success in replication, or adopting in one unit the ideas or best practices developed elsewhere.

An interesting aspect of Solvay's broad-based innovation governance model is that it recognizes that bottom-up innovation, which the company refers to as participative or kaizen innovation, requires different management mechanisms than disruptive innovation, which most often happens in a top-down mode.

Roles for Participative (Kaizen) Innovation

Solvay's participative innovation objective is to tap the brains of the entire organization, down to blue collar workers in manufacturing sites, to generate innovative ideas and to mobilize everyone behind their execution. This objective is illustrated in the management values that are specified in the Solvay Innovation Charter.

Besides the group innovation champion, who supports the overall bottom-up effort, Solvay counts on the involvement of a broad variety of actors through a “central” idea management tool. A 2005 innovation-focused issue of Solvay News describes the role of these actors as follows:

- Innoplace: The intranet-based innovation platform supports the ideation system, which is in place in most entities – businesses and functions – and which covers a number of broad categories of ideas, not just technologies, products, and processes.

- Managers: They are supposed to encourage innovation from all. They facilitate the realization of ideas, recognize the actors and evaluate innovation performance, notably through evaluation discussions.

- Innovation champions (in each main business area and function) and Innov'actors (down to site level in France): They propose innovation initiatives to the managers and execute these initiatives with the staff concerned.

- Facilitators: Within the idea management system, they identify so-called experts and steer the development of ideas.

- Experts: They validate the ideas they receive from facilitators, and they orient the development of ideas within the appropriate innovation structures.

- Employees: They are all expected to submit and react to ideas. They each have a personal annual innovation objective. They keep informed and take frequent initiatives.

Roles and Mechanisms for Disruptive Innovation

Besides focusing on bottom-up innovation, the company has progressively beefed up its ability to generate and steer disruptive innovations to create new businesses. For this purpose, a number of committees and functions have emerged over the years. But since 2010, these various initiatives have been streamlined and consolidated into fewer, more empowered mechanisms. For example, in 2010, management created the position of chief scientific and innovation officer reporting directly to the CEO. It also centralized into an Innovation Center a number of activities pertaining to longer-term, disruptive innovations, e.g. an R&D Excellence function responsible for managing new shared technology platforms, as well as groups responsible for creating new ventures and businesses.

To steer these activities, management converted the New Business Board it had created in the mid-2000s, consisting of Solvay senior leaders and external personalities, into an Innovation Board. It is responsible for managing the portfolio of activities in a prospective development mode, orienting innovation and long-term research programs and developing softer competencies.

In summary, Solvay's top management has launched a number of initiatives and organizational mechanisms to progressively reinforce and simplify its innovation governance practices. Its three original objectives remain to: (1) build new growth platforms and enhance the company's competitiveness; (2) encourage open innovation and partnerships; and (3) engage everyone behind the innovation agenda.

It would not be exaggerating to say that Solvay's long-term objective is to make innovation everyone's business.

As in many innovative companies, Solvay's top management team, through its CEO and its corporate innovation sponsor, is the locus of the company's innovation governance system. But the company uses a number of complementary supporting models to implement its vision of an innovation-driven company and leverage its efforts. To apply our initial terminology of governance models, Solvay's supporting models include a CSO/CIO, a dedicated innovation manager, and a high-level, cross-functional steering group or board, plus a network of champions cascading down to the operational level. Not many companies have such an elaborate innovation governance system.

Solvay's bottom-up and top-down innovation mechanisms have worked well for the company. But there is no doubt that management will have to keep improving and reinforcing its current governance system. As stated in Chapter 4, innovation governance models are bound to evolve as companies grow and new challenges emerge.

The Most Widely Used Innovation Governance Models

Chapter 4 proposed a list of innovation governance models that we had empirically encountered in the course of our innovation management consulting practice. In order to validate this list and identify the most popular of these models, we conducted a selective online survey with 113 companies, half of them global multinationals.1 Indeed, all respondents in our survey recognized their model in the list provided to them, with only minor differences, typically in the naming of that responsibility. So these models provide a fair representation of the range of organizational solutions available for the allocation of overall innovation responsibilities in companies.

Note that, as mentioned in Chapter 4, the same models are also used as secondary or supporting innovation management mechanisms, alongside a primary model. For example, companies that have adopted one of the models in the list for their primary allocation of innovation responsibilities will often choose one or several additional models to enhance and support their primary model. That supporting model can be of the same type as the primary model, but at a lower hierarchical level. For example, if the corporate CTO is chosen as the primary source of innovation governance in a company, divisional CTOs may be assigned a similar responsibility for promoting innovation in their specific organization. But the supporting model can also be of a different nature. For example, when the top management team or the CEO is deemed to be in overall charge of innovation in the company, they may appoint a dedicated innovation manager or a network of champions to leverage their efforts.

Our survey indicates that all these models are in use today, even though some are found more frequently than others. This applies to models for both overall and supporting responsibilities, as shown in Tables 5.1 and 5.2. These tables also highlight that rankings for the frequency of use differ significantly between models for overall and for supporting responsibilities. As we will explore in more detail later, some models, like the innovation manager or the group of champions, are more frequently found in a supporting role than as a primary responsibility.

Table 5.1 Primary Innovation Governance Models Ranked by Frequency of Occurrence

Source: IMD survey (N = 113)

| Who Has the Overall Responsibility for Innovation in Your Company? | In % of Respondents |

|---|---|

| The Top Management Team or a Subset of It | 29 |

| The CEO or Division President | 16 |

| A High-level Cross-functional Steering Group | 14 |

| CTO or CRO | 10 |

| A Dedicated Innovation Manager or CIO | 9 |

| No one specifically | 6 |

| A group of champions | 5 |

| Another CXO or Business Unit Manager | 4 |

| Other | 4 |

| A CTO/CRO with a CXO or Business Unit Manager | 3 |

Table 5.2 Supporting Innovation Governance Models Ranked by Frequency of Occurrence

Source: IMD survey (N = 113)

| Who Plays the Main Supporting Role for Innovation in Your Company? | In % of Respondents |

|---|---|

| The Top Management Team or a Subset of It | 17 |

| A Dedicated Innovation Manager or CIO | 14 |

| The CEO or Division President | 13 |

| A group of champions | 13 |

| No one specifically | 13 |

| A High-level Cross-functional Steering Group | 12 |

| CTO or CRO | 6 |

| Other | 5 |

| Another CXO or Business Unit Manager | 4 |

| A CTO/CRO with a CXO or Business Unit Manager | 3 |

We will now consider each of these models individually and highlight why and how they are used.

The Top Management Team (or a Subset of It) as a Group

In this model, the top management team – or more frequently a small subset of it, often fewer than four senior leaders – exercises overall responsibility for innovation. This seems to be the most widespread form of innovation governance. To reflect the supervisory nature of their mission, some of these innovation-oriented top management teams call their group the innovation board.

This model makes sense if we consider that innovation – a cross-functional and multidisciplinary activity – needs to be steered from the top, with members of the top team contributing their specific competence. Companies like Corning, Nestlé Waters, Lego, and SKF, among others, seem to have adopted this model; but both the size and composition of these groups of top managers in charge of innovation vary greatly from company to company.

For example, many of the adopters of this model in our research sample have limited the membership of their dedicated innovation governance group to those senior leaders most directly linked with innovation activities, i.e. typically a mix of technical and commercial or business leaders. Chief human resources officers, chief financial officers, and other senior staff functions are generally not part of the innovation governance group.

CEOs may include themselves in this high-level steering group – at least officially – particularly in innovation-dependent companies or firms that they founded. In most large corporations, however, busy CEOs tend to delegate day-to-day responsibility for innovation to colleagues within their top management team.

An analysis of what members of this type of innovation governance group actually do shows a diverse pattern of responsibilities and activities (refer to Table 5.3).

Table 5.3 What Do They Do? The Top Management Team (or a Subset of It) as a Group

Source: IMD survey (N = 32)

| Among the proponents of this model: | |

| 69% |

|

| 41% |

|

| 34% |

|

| 31% |

|

| 31% |

|

| 25% |

|

| 25% |

|

| 25% |

|

| 22% |

|

| 19% |

|

The degree of formality with which innovation responsibilities are allocated varies greatly, and this has a strong bearing on the level of satisfaction (or dissatisfaction) with the model, as we shall see in Chapter 6. In its weakest form, innovation is included alongside all other items in the top management team's regular meetings. It is on the agenda, but has no special time allocation. In its strongest form, members of the top management team schedule regular meetings explicitly dedicated to addressing innovation issues; they set up specific innovation objectives and measures; they share among themselves oversight responsibilities for specific projects – typically the ones with a high risk/high reward profile – and they launch various initiatives to promote innovation.

Generally, given its composition of senior leaders, this governance model tends to put stronger emphasis on the content of innovation, i.e. on projects and new ventures, rather than on process. Process improvement issues tend to be delegated to various supporting mechanisms.

Companies that have chosen to allocate overall innovation governance responsibilities to the top management team or a subset of it use a wide variety of other supporting mechanisms to cascade their efforts down the organization.

Not surprisingly, the most frequently found supporting model is the direct involvement of divisional management teams. The second most popular approach is to appoint a dedicated innovation manager to follow through and implement the innovation initiatives adopted at top level. These innovation managers are also generally responsible for proposing improvements to the company's innovation process and tools.

The CEO or Group/Division President (in Multi-Business Corporations)

The CEO as the ultimate “innovation czar” is the second most frequently mentioned model of innovation governance in our sample. It has to a great extent been promoted by a number of charismatic personalities, often direct founders of their companies. No one at Apple would have questioned who was really in charge of innovation under Steve Jobs.

Now, as we mentioned in Chapter 4, the question must be asked, since Jobs' successor as CEO, Tim Cook, may not have the same personality, innovation charisma, and approach. As a consequence, Apple may have to rethink and adapt its innovation governance model to the post-Jobs era. A number of senior executives were involved under Jobs – albeit probably more in a bilateral fashion than as a collective team – and they will certainly continue to be involved, but probably more as a group than as individuals reporting to the CEO. As a consequence – and the future will tell – Apple may well move from the CEO model to the top management team model.

Besides these large innovative companies founded by charismatic CEOs acting as innovation supremos – think of Oracle, Cisco, Amazon, Google, Facebook, and the like – some older companies like IBM, Polaroid, Bose, and Hewlett-Packard were built around that model. Nevertheless, CEOs are rarely the people directly in overall charge of innovation in more traditional large companies. But they can be in small and medium-sized technology-based enterprises and family-owned firms. In large decentralized companies with several divisions or business groups, the heads of these organizations – the business group or division presidents – behave like CEOs of their units and, as such, can exercise ultimate responsibility for innovation in their domain, and this is why they are included in this model.

When the CEO is in overall charge of innovation, the message is usually loud and clear for the rest of the organization – innovation is a top priority – because everyone can observe what is at the heart of the CEO's interest. Will the CEO spend time in design or R&D? Will he/she show a great interest in new products – as Toyota's Akio Toyoda has done, to the point of putting himself in the role of the ultimate racetrack tester of his company's cars? Will he/she encourage the organization to open up to innovations from outside the company as A.G. Lafley did so strongly at P&G? When they take on ultimate responsibility for innovation in their companies, CEOs tend to focus on content issues – i.e. on new technologies and products – more than on process, which they typically delegate to other supporting mechanisms.

However, and surprisingly, as shown in Table 5.4, in only a small proportion of companies that use this model do CEOs get involved in concrete innovation governance tasks, like formulating an innovation strategy or setting innovation targets and measures. CEOs seem to prefer to place their emphasis on attitudes. They preach an “innovation gospel” on all occasions, internally and externally, and they promote innovation values relentlessly, becoming the evangelists of an “innovation ethic,” as Peter Drucker promoted. They generally delegate most innovation management responsibilities to whatever supporting mechanisms they have set up.

Table 5.4 What Do They Focus On? The CEO or Division President

Source: IMD survey (N = 19)

| Among the proponents of this model: | |

| 50% |

|

| 50% |

|

| 33% |

|

| 28% |

|

| 28% |

|

| 28% |

|

| 22% |

|

| 17% |

|

| 17% |

|

When CEOs decide to take on overall responsibility for innovation in their company, they often rely on their top management team and/or on their divisional presidents to support their efforts. In fewer cases, they will mobilize a group of champions to leverage their initiative or choose any one of the other supporting models.

The High-level, Cross-functional Innovation Steering Group or Board

The third model – in terms of frequency of use according to our research sample – can take several forms. Generally, several leaders or managers, chosen from various functions and sometimes across different hierarchical levels, are charged with steering innovation as a group. This model, which may be referred to as the innovation committee, innovation steering group or even innovation governance board, differs from the first model essentially because not all its members are part of the top management team. The chair of such a group is almost always part of the executive committee – it is not infrequent to see the CTO or CRO occupy such a position – but the other members may span a couple of levels under the executive committee.

A number of companies have chosen the high-level, cross-functional steering group or board as a model. Dutch electronics manufacturer Philips, pharmaceutical giants Eli Lilly, Roche, and Sanofi Pasteur, oil giant Royal Dutch Shell, and packaging specialist Tetra Pak are among the companies that have adopted this model.

The norm for these steering groups or boards is to select members on the basis of their functional responsibilities, of course, but also on their personal interest in and commitment to innovation. It is indeed wise to avoid appointing innovation skeptics to such groups, irrespective of their functional responsibilities, and few companies have done that. Some companies make a point of letting some of their younger, most innovative or entrepreneurial managers join the group, possibly on a rotating basis, and this even if those managers remain at a more junior level hierarchically.

Tables 5.5 and 5.6 highlight some of the key characteristics of this model in terms of its composition and empowerment level.

Table 5.5 The High-level, Cross-functional Steering Group or Board Composition

| Among the proponents of this model: | |

| 75% |

|

| 50% |

|

| 19% |

|

| 6% |

|

IMD Survey (N = 16)

Table 5.6 The High-level, Cross-functional Steering Group or Board Empowerment and Mandate

| Among the proponents of this model: | |

| 75% |

|

| 56% |

|

| 44% |

|

| 38% |

|

| 13% |

|

IMD Survey (N = 16)

The level of empowerment of these steering groups or boards varies significantly from company to company. The most surprising element is that only just over one-third of the steering groups or boards represented in our research have access to a dedicated innovation excellence budget, and this limits their capacity to launch costly improvement initiatives.

Some adopters of this model call it the innovation process board which stresses their focus on the process side. One of the key roles of such innovation process boards is to launch a broad range of innovation process improvements and to supervise dedicated process owners. The content of innovation, these companies usually argue, should remain the responsibility of the hierarchical line management, which may not be part of this mechanism.

Other companies, by referring to this body as an innovation governance board, for example, highlight that it is in charge of both content and process. Clearly, the membership structure – in terms of level in the hierarchy and nature of responsibilities – determines whether or not these mechanisms will deal with content issues or only with process management.

On the communication side, 63% communicate regularly upward (to top management) about actions undertaken and progress achieved, whereas only 50% communicate downward about their initiatives and results.

As with the previous models, high-level, cross-functional steering groups or boards do not govern innovation alone. They depend on other organizational mechanisms to implement their policies and decisions. The most frequent supporting model is the dedicated innovation manager, who generally reports functionally to the steering group or board and hierarchically to a member of that steering group or board. Process owners are also frequently appointed to recommend, monitor, and improve specific processes.

Companies with several relatively independent business units may work with additional steering groups or boards at the divisional level, or with groups of champions. But some have no supporting mechanism and rely on the functional organization to implement the process.

The CTO or CRO as the Ultimate Innovation Champion

Allocating responsibility for innovation to the CTO or CRO comes in only fourth place on our list of preferred models. Yet it is probably one of the most traditional forms of innovation governance, particularly for technology-, science-, and engineering-based companies. CTOs are normally found in engineering companies, while CROs (and/or chief scientific officers, or CSOs) turn up more frequently in science-based companies like fine chemicals or pharmaceuticals.

Whatever the title, the CTO or CRO is generally viewed as the promoter of new technology-based products. It is therefore natural for the top management team in companies that strongly equate innovation with new technologies and new products to turn to these talented individuals for all sorts of technology-based innovation initiatives. Companies like Nestlé and Rolex have chosen this governance approach, as has Crédit Suisse. In industries where information technology is predominant – like banks and insurance companies – the equivalent of the CTO is the chief information officer. It is therefore not surprising to see these leaders playing a key role in innovation governance in their companies.

The CTO or CRO model is widely relied upon for innovation in countries with a strong technology and engineering tradition and sector like the USA, Japan, Germany, Sweden, and Switzerland. In these countries, the CTO or CRO may be called senior vice president of R&D and technology, chief engineer, research president, senior vice president of engineering, and the like. But whatever they are called, they are normally full members of the top management team and their colleagues look to them for guidance with regard to innovative developments. In large companies with a management board structure – a traditional form of collegial management in countries like Germany, Switzerland, and the Netherlands – the management board member in charge of technology may not be called the CTO, but he/she will often be viewed as the official spokesperson for and promoter of innovation within the top team.

CTOs and CROs naturally focus on the content of innovation, i.e. on the development of knowledge, technology, and new products. In some companies – particularly technology-intensive Japanese ones – they also focus on new ventures and new business creation, but these are always technology-based. They focus on process issues to the extent that they affect the company's technology and R&D effectiveness. For that purpose, they may set up an ideation and knowledge management process, but they rarely intervene in the non-technical aspects of the company, including finance, business model development, and marketing. The same is true for culture issues: CTOs and CROs may promote a mindset change in R&D – for example, to support cross-disciplinary collaboration, open source innovation, or the creation of a sense of urgency – but they generally do not feel responsible for spreading the effort to the whole organization and supervising the development of innovative processes, for example in commercial operations.

Table 5.7 What are Their Responsibilities? The Chief Technology Officer or Chief Research Officer

| Among the proponents of this model: | |

| 90% |

|

| 90% |

|

| 90% |

|

| 70% |

|

| 70% |

|

| 60% |

|

| 50% |

|

| 50% |

|

| 50% |

|

IMD Survey (N = 11)

Because of their wide-ranging responsibilities, CTOs and CROs tend to exercise their innovation governance responsibilities with the help of supporting mechanisms. Most have their own CTO office, staffed with a few experts on content and process. In Japan, for example, CTOs often set up a small technology planning group to guide them in road-mapping tasks and to assess new business opportunities linked with the adoption of new technologies. In most large companies, CTOs are supported by a more or less formal network of divisional or business unit R&D managers.

The Dedicated Innovation Manager or Chief Innovation Officer

These models are less frequently mentioned than the previous ones but deserve attention nevertheless, mostly because they stress that responsibility for innovation can be entrusted to a single dedicated manager, as opposed to a busy CTO or CRO with operational duties, or to a large steering group, committee, or board. This can be done by appointing a full-time innovation manager (or several of them in a multi-business corporation), who will act as a catalyst for innovation and as the official supporter of the line organization in its efforts to promote an innovation agenda.

Chief innovation officers are generally entrusted with overall responsibility for innovation, whereas innovation managers are more frequently found supporting another governance model. AkzoNobel, DSM, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Herman Miller are among the proponents of dedicating a member of management to innovation.

Innovation managers tend to be chosen from the ranks of highly motivated middle to upper-middle executives from a variety of functions, typically marketing or R&D. They frequently report to a member of the top management team and operate mostly by themselves, occasionally with a couple of staff assistants. They are often responsible for tracking and measuring innovation efforts and results, identifying and sharing best practices, and supporting innovation initiatives launched by the line organization. In that sense, they deal with the process side of innovation much more than the content aspects.

Within these two models, the innovation manager model is more frequently found – and in a broader variety of companies and industries – than its more empowered version, the high-level chief innovation officer (CIO) or senior vice president for innovation. Even though the two functions may look similar in terms of mission, they often differ greatly in terms of access to top management – the CIO typically reports to the CEO – and hence in terms of influence and resources. Unlike innovation managers, who rarely supervise innovation departments, CIOs often have a staff department to support them in their mission, and they are also frequently responsible for the company's innovation acceleration mechanisms, such as new business incubators or innovation hubs. In that sense, they will often be responsible for process and content.

One of the most interesting examples of the empowered CIO model, which will be described in Chapter 10, can be found at Dutch life and materials science company DSM. Not only is DSM's CIO in charge of the company's Innovation Center, with its incubator and emerging business areas, but he also directly supervises the CTO office, hence all corporate technology development activities. This structure, according to DSM's CIO, conveys a strong message to the organization, namely that innovation goes much beyond technology. At DSM, the CIO and his Innovation Center are considered both as the guardians and promoters of innovation excellence within the corporation and as the unit in charge of new business creation.

A Group of Innovation Champions

A number of companies in our survey noted that they have entrusted overall responsibility for innovation to a group of selected champions. In the innovation management literature, champions are often defined as self-motivated upper-middle to senior managers who are not necessarily idea initiators, but who promote the most promising ideas of others in the organization. They secure resources to execute the ideas, often on their personal initiative – more or less independently of top management mandates. They are often self-appointed enthusiasts about the projects they sponsor and are willing to commit personal time and effort in addition to their normal job. They generally operate with the blessing of top management and do not hesitate to take career risks. In that sense, they are and act as innovation accelerators.

These champions focus mainly on the content of innovation, i.e. on specific projects. However, there are a great variety of champions besides the self-appointed intrapreneurs as they are sometimes called. For example, a few companies have appointed idea advocates – usually senior managers towards the end of their careers, who are well respected in the organization. They may volunteer for the role and are assigned by the CEO to make themselves available to help idea submitters prepare and defend their proposals in front of top management.

Some of the less-empowered champions may be chosen by their leaders among middle or upper-middle managers on the basis of their communicable interest in innovation and their energy and drive to stimulate and support management colleagues. They typically focus on the process side of innovation, and they network internally and sometimes even with other companies to share experience and benchmarks.

In our survey, a number of companies, mostly in the USA, reported that they rely on a group of champions to promote and steer innovation. FMC technologies, Hallmark Cards, Bank of America, and Abbott Laboratories are among them. But a company that stands out for having forcefully empowered a group of champions is PepsiCo, particularly under the leadership of its former CEO Roger A. Enrico, who was recognized as a charismatic business builder and marketing wizard. Enrico prided himself on not doing things “by the book,” and he strongly believed that employees are seldom given a chance to fully contribute and show what they can do. So, he selected a group of promising young executives to deploy as business development and innovation champions. He personally coached them and handled their management development at his own ranch.

Groups of champions are more frequently found as a supporting model rather than as a primary innovation governance model.

The Duo (Complementary Two-person Team)

The last governance models are also the least frequently used in practice, at least based on responses to our survey. However, these models do exist; we have seen them in action, in a more or less formal way.

In technology-based companies, the duo may consist of a CTO sharing overall responsibility for innovation with a business unit manager or another functional manager or CXO – for example, a CMO or the company's CFO. In other companies, like banks and financial groups, the duo may bring together a CXO – for example, the chief information officer – and a commercial or business executive.

The idea behind these models is that since innovation is a truly cross-functional activity, it cannot be fully embraced by a representative of a single function – for example, the CTO. The technical and business elements of innovation are therefore entrusted to senior representatives from these functions working together as a team. That last phrase points to an element that is obviously critical and may be difficult to achieve in reality.

No One in Charge

It may be strange to include the absence of a model in our list of innovation governance models. But it does reflect a reality. In some companies, there just is no one officially in charge of innovation. In our experience, there may be several reasons for this.

The first reason – by far the most positive and the first one given in our survey responses – is that innovation is so much part of the company's DNA that everyone feels responsible and acts to support it.

This is based on a management belief that innovation is everyone's task and that the company can therefore count on each function to play its usual role in the process … hence no need for an official mechanism for allocating innovation responsibilities! This type of reasoning may be common in a range of very innovative new companies, for example in the internet area. Some will argue that a bottom-up organization like Google fits in this category because ideas are supposed to come from everywhere in the organization, and everyone is empowered to experiment with them. However, this is debatable given the visionary leadership at play within Google's top management team. Google's founders were clearly in charge of innovation, at least at the beginning.

The second reason for the absence of a governance model may be due to temporary circumstances, such as a restructuring drive or the reorganization of a company. Some companies change their governance models so often – typically at each change of CEO or CTO – that managers may feel that no one is permanently in charge of innovation.

The third reason – which no one in our survey cited, although it exists in real life – is that innovation may not be perceived as really critical by management, and therefore it is deemed unnecessary to allocate specific responsibilities for it. We have come across a few companies in this category. They were typically active in domains requiring strong management emphasis on operational excellence, for example in the shipping industry.

And there is also a fourth reason: There are indeed management teams who are blissfully unaware that innovation will not happen on its own and that it requires some sort of governance.

Combinations of Primary and Supporting Models

As we have seen, all of the models listed above can be used both for the primary allocation of management responsibilities for innovation and for supporting innovation. For example, in one company the CEO could be the person in overall charge of innovation; in another he/she could be supporting whoever is entrusted with overall responsibility.

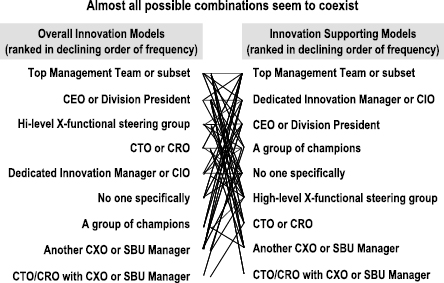

Interestingly, our survey results indicate that almost all combinations of primary and supporting models exist. For example, if the primary model is the top management team or a subset of it, some companies stated that the CEO is a supporter of the top team, while others relied on a cross-functional steering group for this. Yet others considered it to be the role of the CTO to act as supporter, and so forth. Figure 5.1 illustrates these multiple combinations.

Figure 5.1: Combinations of Governance Models

Additional Innovation-supporting Mechanisms

Most companies do not restrict themselves to one primary governance model and only one supporting model. Like Solvay, many use a number of additional sources of help to support their innovation governance efforts. For example, besides relying on corporate innovation-oriented functions, such as R&D, design, new business development, incubators, and the like, most companies in our survey sample mentioned using at least one and often several of the following mechanisms:

- Thirty-two percent have appointed one or several innovation managers reporting to senior management. These innovation managers, who come as the third element of their innovation governance system, are generally middle to upper-middle managers embedded in the corporation's various organizational units. Their mission is similar to that of higher-level innovation managers – to help local managers launch innovation initiatives and support innovation projects, albeit in the units to which they are attached.

- Thirty-two percent rely on selected business managers appointed as innovation sponsors. The use of project sponsors is widespread in new product development as it allows management to ensure that projects meet an essential business need and proceed smoothly. But the same business managers can easily broaden their role and sponsor all kinds of innovation-enhancing initiatives.

- Twenty-nine percent have set up a dedicated innovation department with its own staff resources. Such departments are found primarily when the company has entrusted innovation responsibilities to the CTO/CRO or to a high-level chief innovation officer. These innovation departments typically focus on process excellence, best-practice sharing, and innovation performance tracking. Some of them – sometimes called innovation acceleration teams, as in Nestlé – serve as internal consultants on innovation.

- Twenty-four percent call on external resources – typically management consultants – to help on critical innovation tasks. On the process side, consultants are often asked to provide assistance with technology road-mapping, voice of customer research, benchmarking to help establish a diagnostic of innovation obstacles, or to propose or improve a phase review product development process. Some companies use them more broadly, for example to restructure innovation-oriented departments like R&D. On the content side, consultants' help may be used to optimize a product portfolio or launch market feasibilities for totally new concepts.

- Sixteen percent have deployed a network of officially designated innovation coaches. These innovation coaches are usually different from the innovation sponsors mentioned above. Whereas sponsors support teams and initiatives at the management level without necessarily becoming personally involved, innovation coaches tend to be much more hands-on. They are high-level champions who are accessible to everyone who has an idea, and they will work with idea submitters to refine their original ideas and ensure they are receivable by management. In many companies, these innovation coaches – or innovation advocates as they are sometimes called – are managers in the last years of their career with an interest in innovation, strong personal credibility, and a broad personal network which they can bring to bear on specific innovation projects.

In summary, as we stated at the beginning of this chapter, most companies have deployed a broad range of organizational mechanisms to govern and manage innovation. In the next chapter, we will indicate how the companies we polled evaluate their level of satisfaction or dissatisfaction with their chosen governance model. We will also highlight some of the factors that affect the effectiveness of each of these models.

Note

1 This survey was conducted with 113 companies mostly in Europe and the USA. The respondents came from the following industries: healthcare (18); engineering (16); electronics (17); fast-moving consumer goods (13); trade and services (11); other consumer goods (8); financial services (6); chemicals (6); telecom operators (4); software (4); utilities/energy (3); materials (3); other industrial products and anonymous (4).