CHAPTER 14

Aligning Individual and Collective Innovation Leadership

This book is based on a core belief, namely that sustained innovation performance is conditioned by the quality of the company's innovation governance. Management teams that are not fully satisfied with their innovation governance system – and Chapter 6 showed that they are numerous – need to start by building and sharing a vision of the desirable improvement path ahead. As with all major change efforts, a leap in innovation governance effectiveness requires a three-phase approach:

Chapter 13 recommended reviewing and assessing your innovation governance system on the basis of eight factors. The first and most important is an attitudinal element that everyone in a company can observe, namely the level of commitment and engagement by the top management team, and particularly the CEO, behind innovation and the chosen governance model. Such an attitude reflects a combination of individual and collective innovation leadership.

Indeed, to thrive, innovation requires two things: First, members of the top management team should share the same set of beliefs and values regarding their role, and behave consistently as innovation leaders, every day and in every situation. Second, C-suite members should work together as a cohesive team, complementing one another in terms of talents and styles.

For this to happen, everyone in the management team must start with a personal reflection and self-examination to assess:

The results of these individual self-assessments ought to be shared openly and constructively within the top management team, for example during a vision-building workshop to devise a better innovation governance system. The best way to initiate a new vision is to start by taking stock of the current situation, aspirations and predispositions of everyone in the team. Note that this leadership appraisal process has fruitful applications for all kinds of corporate change initiatives, not just for innovation governance.

Let's review each of these four leadership elements.

Do You Meet the Main Leadership Imperatives of Innovation?

The book Innovation Leaders mentioned in Chapter 1 addressed an important question: Is there a special type of leadership for innovation – the answer was clearly yes – and, if so, what are its main characteristics?1 The book proposed six behavioral traits of innovation leaders. In addition, it suggested that innovation leaders do not necessarily share the same interests and talents. Some are more attracted by and predisposed to become involved in the creative front end of innovation – typically dealing with technologies, ideas, and concept portfolios. We call them front-end innovation leaders. Others, or back-end innovation leaders, naturally focus on the operational side of innovation and managing projects from concept approval to market launch and roll-out. It is therefore advisable for each member of the C-suite (1) to review these six behavioral traits and assess whether they are being met, individually and collectively, and (2) to identify who in the team falls naturally at the front end or back end of innovation.

Do You Generally Behave Like an Innovation Leader?

Trait #1 – Do You Show Signs of Both Emotion and Realism?

Using a description proposed by Daniel Borel, the entrepreneurial founder of Logitech, the first leadership trait of innovation leaders is their ability to combine a genuine interest in creativity with close attention to process discipline. Of course, innovation leaders encourage and support innovators and are open to their ideas; they also ensure that their staff design and use a process to generate, acknowledge, screen, and rank ideas before they can be validated and turned into potential projects. At the same time, they are pragmatic and involved in all the critical project execution tasks that require a lot of implementation discipline. Of course, some leaders lean more to one side than the other, but the two aspects – creativity and discipline – need to be well represented within the top management team. Given the usual cross-functional composition of most executive groups, which consist of creative marketing and technical leaders as well as more operational ones, this first innovation leadership trait is likely to be well met as a group.

Trait #2 – Do You Accept Risk and Failure and Promote a Passion for Learning?

This second trait, or at least the first part of it – acceptance of risk and failure – is generally recognized as the main attribute of innovation leaders. In fact, the important aspect is the second element: a passion for learning from experiments and mistakes. The only benefit of a bungle is that it makes people reflect, learn, and become wiser. This is why innovation leaders make a point of exhorting project teams to systematically organize honest debriefing sessions at the end of each project – particularly if it fails – to understand the mistakes that were made and draw lessons. In assessing the extent to which they meet this requirement, leaders have to be candid with themselves and look at the reality, which means being conscious of their actions, not only their words. Questions to ask include: Do we seriously analyze our failures and try to understand their root causes? What really happens in our company with the teams and project leaders that fail? Will the people involved be penalized in their career? If the justification for failure is learning, then innovation leaders must also make it clear that repeating the same mistake is unacceptable.

Trait #3 – Do You Have the Courage to Stop Projects, Not Just to Start Them?

Innovation has to do with starting new things, so new project ideas tend to abound in innovative companies. One of the critical leadership roles of top management is to ensure that the portfolio of projects meets the company's objectives and strategies and bears a reasonable chance of success. This implies the need to prune projects that either do not fit with the strategy or show a dubious outlook in terms of market impact. This mission, which is often unpopular with project initiators, assumes that management is able to exercise discernment about the future of a project if it is continued. It raises the difficult question of when to persist or when to pull the plug. Innovation leaders tend to rely on two elements to make such a decision. The first is a deep gut feeling about the superior customer value that the project will create if it is successful. The example of Nespresso, described in Chapter 9, illustrates this point convincingly. Some members of Nestlé's executive group were indeed so convinced of the superiority of the espresso produced by their new system that they agreed to keep funding the project for 16 years. The second argument in favor of persisting with an uncertain project is when customers express a strong interest in the project outcome.

Trait #4 – Are You Good at Building and Steering Teams and Attracting Innovators?

If invention can be an individual phenomenon, innovation is always the result of a team effort, as noted by Ed Catmull, co-founder of Pixar and president of Pixar & Disney Studios.2 It is therefore not surprising that innovation leaders pay a lot of attention to the teams they have assembled for an innovation project. The first thing they do is to select team members carefully in order to balance skills, experience, and personalities in an optimal way. This implies that they do not pick team members on the basis of who is available, but on who will bring the best contribution to the project. In some companies, like Sony, this goes as far as giving the leaders of critical projects a free hand to raid the entire organization to find the talents they need, irrespective of departmental turf lines. Once teams are brought together, innovation leaders take care of their resource and coaching needs, and they open their door for advice, as needed, but without interfering in the team's work. Innovation leaders value and trust teams, and they know how to recognize and reward them, which makes them popular with innovators.

Trait #5 – Are You Open to External Technologies and Ideas?

Innovation leaders promote openness across all functions and they encourage their staff to go out, broaden their horizons, and build external networks. Once again, as for tolerance of failure, there is a gap between preaching the open innovation gospel and practicing it in reality. Some leaders talk officially about the need to go out and be open, but in fact resent seeing their staff take time away from their normal work to build external relationships and explore idea and technology sources. In most companies, marketing people are expected to go out and meet information sources in the market to identify new trends and detect ill-met, unmet, or latent customer needs. Similarly, technology specialists in R&D are encouraged to establish networks in their scientific community to build intelligence and identify promising new technologies. What is less common is to see marketers and technologists engage in common exploratory market trips. And yet, a cross-functional exposition to the market and a confrontation of ideas are often the most fruitful ways to develop innovative concepts. So, innovation leaders need to encourage these experiments.

Trait #6 – Do You Show Passion for Innovation and Share it Widely?

A common element in the personality of innovation leaders is the high level of energy and enthusiasm for innovation that they convey to their staff. This passion can generally be communicated because passionate leaders tend to attract passionate followers. Daniel Borel was known for his passion, and he insisted that it be one of the important elements to be detected through personality tests for new job candidates.3 Of course, being passionate about innovation does not mean being blind to the risks involved. It means being determined to conduct projects, to make them successful, and also, as mentioned above, to know when to stop them.

Are You a Front-end or Back-end Innovation Leader?

Innovative companies generally have a number of innovation leaders in the organization, including of course in the C-suite. To succeed and sustain innovation, they need the right combination of front-end and back-end leaders, since the two types are complementary. In pharmaceutical firms, front-end leaders are typically found among the heads of discovery, under the leadership of the chief research officer, whereas back-end leaders tend to be in charge of clinical development, manufacturing, and marketing and sales. It is generally relatively easy to identify these two types of leaders because of their functional orientation and also their general management interests and attitude.

Steve Jobs was undoubtedly a front-end innovation leader at Apple and he exemplifies the profile of these promoters of radical creativity:

- Passion for new ideas, new products, and new designs to meet customers' unarticulated needs or improve their experience.

- A bias toward questioning the status quo and challenging staff with all kinds of questions: why? what if? what else? why not? who? who else? how much? how? how else?

- Adoption of a VC-like philosophy regarding returns, i.e. knowing full well that only a fraction of new ideas and projects will succeed, and thus focusing on those with a big win promise.

- Willingness to experiment and open new paths, which means accepting risk and tolerating failure.

- Ability to promote individual and team freedom and create a climate of mental adventure and excitement that will naturally attract innovators.

Tim Cook, who replaced Jobs at the head of Apple, is an archetypal back-end innovation leader. He is known for having superbly handled Apple's supply chain, manufacturing outsourcing and logistics, thus freeing Jobs to focus on his front-end interests. Cook probably meets several if not all of the characteristics of back-end innovation leaders, who are the proponents of operational discipline:

- Focus on getting products to market flawlessly and cost-effectively by mastering all the operational foundations necessary to go smoothly from concept to launch and roll-out.

- Insistence on planning quality as well as on process discipline and standardization to make innovation replicable.

- Demand for speed to market through a high level of cross-functional integration and a first-time-right philosophy in implementation.

- Flexibility in execution decisions, based on operational knowledge and pragmatic risk management.

- Ability to motivate staff for product battles and promotion of a “launch and learn” approach, possibly leading to product improvements and relaunch cycles.

Besides identifying front- and back-end leaders, their position in the organization and their respective clout, management needs to ensure that the handover between them is smooth, which may not be easy given their very different personalities and leadership styles. In appointing an innovation leader as CEO, boards should be aware of the implications of their choice. If they appoint a front-end innovation leader like Jobs at the helm of the company, who will take care of the disciplined operational side? And if they choose a back-end leader as CEO, like Cook, who will defend an aggressive front-end agenda?

What is Your Own Leadership Model?

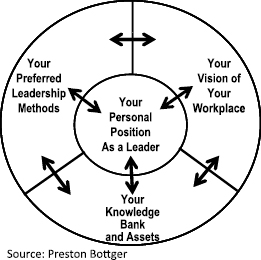

Besides reviewing the leadership imperatives for innovation, members of the top team – and more generally all senior leaders – need to reflect on what drives them as individual leaders. Preston Bottger, who teaches leadership and management development at IMD business school in Lausanne, believes in Lao Tzu's famous observation: “He who knows others is wise; he who knows himself is enlightened.” This is why he advocates that every manager who aspires to a leadership position should reflect on his/her own model of leadership. This, he suggests, implies assessing four elements and understanding how these elements support, or sometimes conflict with, the company's position and its innovation challenge (refer to Figure 14.1).

Figure 14.1: Characterizing Your Own Model of Leadership

At the center is the first element, your personal position as a leader, including your hierarchy of motivations and drivers – both intrinsic (i.e. personal and deep-seated) and extrinsic (i.e. influenced by your external environment). Recognizing your individual motivations and making them explicit is important as a first self-assessment step for innovation governance:

- Why do you want to promote an innovation agenda?

- What would you like to achieve, individually and collectively?

- How much energy are you ready to invest to meet your objective?

- What's in it for you, personally?

- What do you like and dislike about steering innovation?

- What are your beliefs about what it will take to succeed?

- What are you ready to do to show your commitment?

- What are you ready to give up? (If anything.)

- How long you are ready to go on for?

The second element, according to Bottger, is your knowledge bank or your personal assets for governing innovation. This includes:

- your individual talents and skills, i.e. what you are good at;

- your past experience with innovation and change management;

- your knowledge of how the company works and of the location of its untapped potential;

- your internal and external networks; and

- your access to information, concepts and tools relevant for innovation.

The third element is your preferred methods for gaining and exerting influence and introducing change:

- Do you believe in personally showing the way through your acts and decisions?

- Are you an adept of persuasion through rational argument?

- Do you prefer to call on people's emotional intelligence and followership?

- Are you afraid of a confrontation of ideas?

- Do you feel comfortable building coalitions toward a common objective?

Finally, the last element of your personal model of leadership is your vision of your workplace. This includes:

- your perception of your management team effectiveness and of its inner workings;

- your understanding of your company and of its strengths and weaknesses;

- your assessment of your industry and where it is heading; and

- your vision of the broad environment in which your company is operating.

This first self-assessment can be complemented by characterizing your leadership style and understanding how your type of leadership matches some of the imperatives for an effective governance system.

What is Your Own Innate Leadership Style?

Being aware of your own leadership style and that of your management colleagues is a difficult but useful undertaking. A number of models have been developed over the years for this purpose. The most widely used – the Myers-Briggs personality typology – is useful for defining the psychological underpinnings of a leadership profile. But it is not easy to make it operational as a leadership model because of its complexity, notably because of its 16 types. As a consequence, and for our purposes, we prefer to use a simpler model, developed by management author Robert Tomasko4 for his consulting clients. Experience shows that this model is very intuitive, i.e. people can easily recognize themselves and their colleagues in this typology, just by reviewing the descriptors of each style.

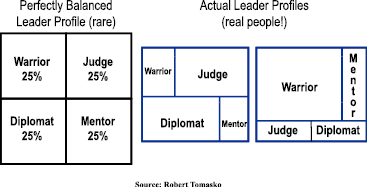

Leaders – suggests Tomasko – need to develop four complementary abilities:

- To be aggressive, like a warrior.

- To be conserving, like a judge.

- To adapt to situations and people, like a diplomat.

- To support people and ideas, like a mentor.

Every leader has a combination of these four characteristics in different proportions, and the combinations vary from one leader to another. In most cases, leaders feature one (and sometimes two) of these four traits as their major, i.e. they instinctively behave according to their major trait, even though they can proactively bring their other traits to bear as minors in different proportions and situations (refer to Figure 14.2 for an illustration).

Figure 14.2: Every Leader Features a Combination of Four Traits

This simple typology of leadership styles is relatively easy to use. Our experience shows that the descriptors of qualities and excesses for each of these four leadership styles, which are listed in the following paragraphs, are sufficient for anyone to detect the major and minors of everyone in the management team.

Let's review each of these four archetypes, characterize them in terms of philosophy and behavior, and indicate where, on the innovation governance front, they can be either particularly effective or, in some cases, dysfunctional.

Are You Primarily a Warrior?

Warriors are action-oriented, dynamic leaders. Their philosophy is: To be successful, you have to make things happen! Warriors are proponents of a “just do it” approach, rather than of thorough analysis and planning. They also naturally tend to promote outside-in perspectives and approaches. Because of their qualities – they are typically masterful, confident, persuasive, risk taking, and forceful – they are at their best when the name of the game is taking charge and showing initiative. But these qualities can be pushed to an extreme, thus leading to questionable behavior. They can indeed be domineering in dictating assignments and approaches, instead of being masterful; their confidence can turn to arrogance; they may be coercive with staff instead of persuasive; they may favor gambling rather than risk taking; and they can be seen as pushy rather than simply forceful. So, extreme warriors may not be effective when a situation requires the art of delegating and winning cooperation.

Leaders whose major trait is the warrior are competent in all innovation governance tasks that deal with adopting a bold vision and game plan, spotting new business opportunities, sponsoring high-risk, high-reward projects, launching new products, and creating new ventures. They are also forceful in pursuing acquisitions to complement their company's technology profile or reinforce its market base. On a people motivation side, they typically attract and motivate business-oriented innovators and self-starting entrepreneurs through their dynamism and “go get it” approach.

However, uncontrolled warriors may feel, and give in to, the urge to work against the principles of governance, which at its most basic level demands cooperation and dialogue – and, of course, following the rules. They may trigger resistance and frustration, particularly within functions and units outside their organizational turf, e.g. marketing if they come from the R&D side; R&D if they are from marketing; market companies if they are at headquarters, etc. They may also act more on instinct or gut feeling than through thorough analysis of the facts and careful planning. They may establish key performance indicators but may not always base their actions on indicator trends if these go against their perception of reality. Warriors accept data that confirm their opinion, but they might dismiss facts that go against their vision and mental model. Some of them do not hesitate to artificially generate the kind of data that justify their undertakings. Additionally, they may be inappropriate for leading complex negotiation deals related to innovation partnerships, given their impatience, forcefulness, and lack of diplomacy.

Some of the shortcomings of full-blooded warriors can in fact be reduced by their other, secondary traits. For example, if warriors have a judge element as secondary leadership trait, their reluctance to engage in data analysis and planning may be subdued. If they have a diplomat tendency as a second trait – an infrequent occurrence, though, because the two profiles tend to be incompatible – they are definitely in a good position to lead partnership discussions. If they have a significant mentor overtone in their profile, they may be in a better position to marshal the energies of their staff to achieve their objective and obtain cooperation.

Are You Fundamentally a Judge?

Judges are “no-nonsense” leaders with a bias for solid analysis. Their philosophy is: To be successful, let's base our decisions on facts! In this sense, they are the opposite of the more instinctive warriors. Their qualities – they are practical, economical, tenacious, reserved, thorough, and detail oriented – make them indispensable when important decisions need to be based on thorough analysis, and when pros and cons must be carefully evaluated before acting. But, as for warriors, the qualities of judges, if taken too far, can become detrimental. Their practical sense may lead to unimaginative behavior; their economical bias, if excessive, may make them stingy; their tenacity can turn into rigidity; their reserved behavior may lead to their being perceived as dull; being thorough may cause them to be overelaborate; and their detail orientation could mean they are seen as being data-bound. All of this may prevent them from reacting quickly and improvising in an emergency. In the worst case, judges are at risk of falling prey to the famous analysis–paralysis syndrome.

Leaders with a definite judge style can play an important role in innovation governance. Their bias toward rigorous analysis ensures that important decisions, for example on make-or-break projects, are carefully evaluated, thus limiting the risk of failure. They are also capable of establishing and standardizing complex processes. They are good at organizing functions, defining roles and responsibilities, and streamlining decision procedures. As proponents of the classical saying “Things that cannot be measured cannot be improved,” they naturally tend to establish and monitor performance indicators. Because of their trustworthiness, judges are typically appreciated by the company's controller and CFO – archetypal judges themselves – and they can play a major advisory role vis-à-vis the CEO.

However, their attention to detail may make them unpopular with the more instinctive innovators and entrepreneurs. Overzealous judges may indeed slow things down, particularly in the action-intensive product development and launch phases of the innovation process, which require quick decisions and reactive management. They may also restrain management from taking innovation risks, for example in pioneering a new technology, introducing a totally new product category, and being first in the market.

The above descriptions characterize full-blooded judges. In reality, however, as with the other three styles, leaders operate on the basis of their major trait, but its excesses are most frequently offset by their minor traits. This applies to judges particularly when their minor trait is diplomat or mentor. Either of these dispositions can make them more sensitive to the personal views of their subordinates, thus more effective when challenging projects and decisions. A judge with a warrior minor – an association often found in CEOs, although the reverse is more frequent – combines the best of both worlds, i.e. a realistic approach to risk taking.

Do You Behave Like a Diplomat?

Diplomats are leaders who believe that a harmonious organization performs better than a dissenting one, so they listen to the opinions of their teammates and staff before making decisions. Their philosophy is: To be successful, let's ensure everyone gets a fair deal and is able to contribute his or her best talents. This predisposition makes them more inside-out oriented than warriors. Given their qualities – diplomats can be flexible, willing to experiment, tactful and patient, socially skillful, and to certain extent shrewd – they are at their best when making trade-offs and handling cross-functional conflicts. But, as with the other traits, these qualities can turn into limitations when applied with excessive zeal. Their flexibility, when carried to an extreme, may make them inconsistent; their bias toward experimentation may make them reluctant to commit to a course of action; their tact and patience may make them overcautious; their attention to social skills may turn into indecisiveness; and their shrewd approach to human relations may be perceived as a desire to manipulate people. In short, diplomats may not be good at forcing a decision and sticking their neck out on a given course of action.

On the innovation governance front, diplomats are likely to be effective in establishing what we referred to in Chapter 1 as an innovation constitution, defining unambiguously the roles and responsibilities of various functions and units in innovation. They are talented at solving turf conflicts and ensuring everyone paddles in the same direction. As members of top management, they can facilitate the emergence of a consensus on important decisions on strategy, projects, and funding. Their role is also important in managing open innovation initiatives and partnerships, since they strive to achieve win–win deals.

But overcautious diplomats, particularly if they water down imaginative concepts to please everyone, may lead the company to develop dull products. An urge for consensus can indeed be dysfunctional in innovation. Diplomats may be reluctant to see conflicts emerge on innovation ideas, particularly if these ideas have reached the top management team.

As with the previous profiles, leaders with a diplomat character trait may see the risk of dysfunctional behavior reduced by their secondary leadership style. We have already mentioned that leaders with a strong diplomat style are infrequently associated with warrior characteristics. They can, however, combine common traits with judges and this may make them more practical and decisive. When they combine a diplomat and mentor profile, a frequent occurrence, they are likely to be excellent developers of human resources, notably of future innovation leaders.

Do Your Staff Consider You as a Mentor?

Mentors pay close attention to the personal development of their staff, coach them, and sponsor their initiatives. Their philosophy is: To be successful, we need a team of motivated people whose talents are being used in a right way. Their qualities – they are considerate, somewhat idealistic with regard to the potential of their staff, modest, supporting, and responsive – make them accomplished at working with others and developing team members. They are often seen as the wise leaders whom people go to when they have a problem to which they see no solution, or when they enter into a personal or professional conflict with colleagues. But mentors' qualities, if pushed too far, can have a negative impact on their effectiveness as born leaders. An overly considerate attitude may be perceived by some colleagues as softness; their idealistic view of people's qualities can be interpreted as gullibility; their modesty may make them unimposing; their supporting attitude can be seen as paternalism; their responsiveness may verge on passivity. These excesses make them ill-adapted to promoting an outside-in attitude in their organization and in gearing up their staff to fight tough competitive battles.

Leaders with a definite mentor profile can play an important role in innovation governance, for instance by aligning people behind the company's innovation agenda and promoting corresponding values. Their strong people orientation makes them indispensable to the top management team as advisers when allocating innovation responsibilities or appointing innovation teams. They can also detect opportunities for improvements in the company's innovation climate and identify obstacles that management needs to overcome. They tend to be keen to launch management development programs to fill gaps in innovation-related skills. Finally, they are useful in handling interpersonal conflicts within innovation teams or between functions.

But because of their innate bias toward looking inside the organization, mentors may not be effective in leading their staff into product battles. By focusing their energy on handling internal interfaces rather than becoming immersed in the market, they may miss innovation opportunities. They are therefore dependent on the motivation, external orientation, and self-starting attitude of their colleagues.

If mentors feature a warrior minor, which introduces an outside orientation and a bias for action, many of their shortcomings will be mitigated. In fact, a warrior/mentor combination can be extremely appropriate for leading an innovative organization. Mentors can also have judge overtones, which give them a more analytical – less emotional – approach to managing people, teams, and processes. When combined with a diplomat minor, mentors can be competent at handling complex negotiations, for example with partners.

How Do You Leverage Individual Talents to Create Effective Innovation Teams?

Tomasko's typology of leadership styles can prove useful when deciding about allocating responsibilities for innovation. It is worth stressing that there is no hierarchy among these four styles. Each has its strengths and can contribute to steering innovation and aligning people behind an innovation effort. Each also includes a number of biases and weaknesses, which must be recognized. This underscores the importance of combining complementary profiles within management and innovation teams to achieve balance.

New product development projects are often, intuitively, assigned to warrior leaders because they tend to be professionally aggressive, proactive, risk taking and market oriented. But at the same time, teams need rigor in analysis, methods for minimizing uncertainty and risk, and a disciplined process for navigating through the project gates. This may require a second in command with a strong judge inclination, i.e. a thorough and prudent leader.

If the project team is not balanced across all profiles, this can be achieved by paying special attention to the composition of the project review team – the higher level committee in charge of challenging the project team and approving its completion of the requirements of each gate. If there is no warrior profile in the project team, for example, then the chair of the review committee should be a warrior type to invigorate the team, create a sense of urgency, and stress the need to be market oriented. If the project team is in the hands of a strong warrior leader, then the review committee should be composed of judges and diplomats, the latter to smooth interfunction relationships, notably regarding turf sensitivities and conflicts over resource allocation.

Similarly, the top management team can apply this typology within the innovation governance model. For example, if the primary responsibility for innovation is allocated to a single person, e.g. to the CTO or the CIO, then the natural leadership style of that person needs to be recognized. If this leader is perceived by peers as a true warrior – as happens frequently because companies like to appoint doers in this position – management would do well to recommend that the warrior appoints people to work with him/her who have a complementary profile. Whether consciously or subconsciously, leaders often look for a second in command or assistants who have the same major leadership trait as they do. Warriors, for example, may be tempted to surround themselves with other warriors, simply because they feel more comfortable dealing with people like themselves. However, a warrior CTO or CIO needs a judge as his/her assistant to handle the disciplined part of the job, for example the standardization, improvement, and supervision of processes, and the implementation and tracking of innovation performance indicators.

The challenge is obviously easier to address when the governance model allocates innovation responsibilities to a group of leaders, such as the subset of the top management team, or the high-level innovation steering group or board – which has managers spanning different hierarchical levels. In these cases, it is desirable for the leaders in question to possess different styles, thus ensuring that the group is reasonably balanced in terms of leadership profile.

Aligning Leadership and Innovation Governance

To close this reflection on leadership and governance, it may be useful to briefly review why innovation leadership provides a foundation from which effective governance will emerge.

Why Does Innovation Need to be Governed?

As we have pointed out, innovation is a highly complex corporate activity, which crosses many of the boundaries that exist in most companies.

The kind of governance that emerges naturally in a complex system with many groups that have differing goals, expertise, and interests is typically tribal – each group possesses its own rules and its own judgment of what is important. As sociobiologist Edward O. Wilson put it in a chapter entitled “Tribalism is a Fundamental Human Trait”: “to form groups, drawing visceral comfort and pride from familiar fellowship, and to defend the group enthusiastically against rival groups – these are among the absolute universals of human nature and hence of culture.”5

Anyone who has been in the position of managing or leading innovation has no doubt come across the functional tribalism that can defeat innovation – whereby innovators want the most radical breakthrough solution they can imagine, engineers want to spend years perfecting one aspect of the innovation, manufacturers want to preserve the efficiency of their processes, sales just wants something that will please their current customers (e.g. something faster or cheaper or prettier), and so on. These are not simply differences of opinion – these are core beliefs about what is essentially important. This is why innovation needs to be governed.

Why Should Innovation Governance Models be Made Explicit?

As we have just seen, tribalism is one form of governance that emerges in complex companies in the absence of an explicit model. In addition to tribalism, companies may exhibit governance models that resemble democracies, republics, monarchies, aristocracies, plutocracies, dictatorships, and of course the lack of government, or anarchy.

The tacit models of government that large and complex systems adopt do not usually provide the best possible methods of coordination and execution. Corporate democracies are often extremely inefficient. Aristocracies or monarchies, where the senior leadership is automatically chosen from among the elite – be they members of the founding family or of some other inner circle – do not look widely for appropriate leaders and are often subject to conservative and tradition-bound thinking. Dictatorships may become tied to the inspiration, personality, operational style, and judgments of a particular leader, with disastrous consequences when that person retires. Any tacit form of government is likely to be held captive by a limited scope of knowledge, information, and relationships as leaders assume that their knowledge, their world view, is the best one – or perhaps the only one. This is true for corporate governance in general; it applies also to innovation governance.

The alternative, then, as we have argued throughout this book, is to make the company's model of innovation governance explicit, for example in an innovation constitution.

Governing Relates to Knowing What You are Doing

Sometime in the later decades of the 20th century, innovators (then called new product developers) began to ask what would make their work more successful. Would it be useful to gather together teams with members who represented the tribal functions early in the process? Was there a way to outline the decisions that needed to be made and the tasks that needed to be undertaken in order to get an idea to market? How could the likely success or failure of a project be assessed before too many resources were allocated to it, and how might the company be able to align its product strategy with the actual projects that were being resourced?

As these and other fundamental questions were raised, and as companies discovered ways of addressing them that created a discipline around the enterprise of innovating, the boundaries of the activity expanded to include both purposeful exploration of new opportunities and the introduction of innovation partners. The digitization of information and globalization added to the complexity, but also to companies' ability to draw on vast resources while at the same time being able to coordinate means and information.

Corporate leaders and innovators now have access to the world at the click of a mouse. They can gather and communicate critical information in the form of maps and diagrams that reveal not only data but also context. They have designed and implemented processes and practices that foster genuine communication and understanding among their “tribal groups” as well as with partners and customers. And yet, even with all of this in its favor, in many instances innovation seems not to be working as well as we might expect.

Now is the Time to Start Governing Innovation

Happily, there is a better way. First of all, innovation has become governable. That is, top management now has many tools to enable it to set innovation goals and objectives, to measure progress – or the lack thereof – towards these goals, and to assess what is contributing to success or failure. Second, innovation has become, for most companies, an inescapable issue of basic survival in this fast-moving and networked world. Third, innovation, unlike new product development, regularly requires the company to make decisions that challenge its core identity – for example, moving to new business models, partnerships, and new businesses – and this requires the explicit participation of empowered individuals or groups in the company.

Many of the companies we have written about derived their governance model from an understanding of their history and culture – the basis of their innate or tacit models. Some drew on models they were familiar with at other companies. All took into consideration their strengths and weaknesses, and we believe that none of them thought that the model it implemented would necessarily work forever – i.e. they are open to, even committed to, changing and improving the model.

We predict that as governance increasingly becomes an explicit matter of concern, management's ability to set innovation goals and agendas and to move effectively toward accomplishing them will improve markedly. We also suspect that success in governing innovation will open up new areas that cannot now be predicted. But we know that the key ingredients for participating in whatever the new world brings will still be effective governance, leadership, and collaboration.

Notes

1 Deschamps, J.-P. (2008). Innovation Leaders: How Senior Executives Stimulate, Steer and Sustain Innovation. Chichester, Wiley/Jossey-Bass.

2 Catmull, E. (2008). How Pixar Fosters Collective Creativity. Harvard Business Review, September: 64–72.

3 Videotaped interview with Daniel Borel, former chairman of Logitech, on “Innovation & Leadership,” IMD, 2003.

4 Robert M. Tomasko is a management author and consultant who has written four best-selling books: Downsizing: Reshaping the Corporation for the Future, New York, Amacom, 1987; Rethinking the Corporation, New York, Amacom, 1993; Go for Growth, Hoboken, John Wiley & Sons Inc., 1996; and Bigger Isn't Always Better, New York, Amacom, 2006. He directs the Social Enterprise Program and holds a faculty appointment at American University, where he teaches graduate courses in corporate social responsibility, effective activism, leadership, NGO management, and social entrepreneurship.

5 Wilson, E.O. (2012). The Social Conquest of Earth. New York, Liveright Publishing Company, p. 57.