CHAPTER 12

Getting Started

How Michelin has Rethought its Governance Model

Throughout this book, we have advocated the need for innovative companies to regularly review their approach to governing innovation in order to make it more effective. Some companies do it on an incremental basis, perfecting their system while keeping the same organizational model. Others adopt a more radical approach by exchanging their traditional model for a totally new way of allocating responsibilities and governing innovation. This is what Michelin, arguably the world's most innovative tire company, has done.

There are, generally, several drivers of this more radical type of change. It frequently starts with a management desire to broaden the company's scope of innovation and/or boost its performance given new market and competitive developments. But it is also frequently triggered by a change in top management and the arrival of a CEO with ambitious growth objectives and the will to leverage innovation as the main driver of that growth. This is what happened at DSM around 2005 and this is the process that Michelin has embarked on recently.

We believe that the path Michelin has followed in questioning its past practices, streamlining its innovation process, and coming up with a new innovation ecosystem – all of it achieved in a couple of years – should inspire many companies and show them one way to go. Michelin has reinvented its innovation governance model, and it has done so through deep personal engagement at the very top of the company. The management team does not claim that the system is perfect, yet, but they remain fully committed to keep improving it.

A Long History of Innovation in Transportation

Pioneering Rubber Tires

The roots of Michelin go back to 1832 in Clermont-Ferrand, in the Auvergne region of France, when two entrepreneurs applied a British invention1 to produce a variety of rubber products. They built a small manufacturing plant and set up a partnership limited by shares in 1863. The company became Michelin & Co. in 1889 when two brothers from the founding family, Edouard and André Michelin, started to exploit a new rubber brake pad for horse-drawn carriages, “The Silent.” This marked the beginning of the company's activities in rubber-based products for facilitating transportation and mobility, a mission that continues to guide the company today.

Most Michelin observers attribute the company's ability to sustain innovation to the strong and visionary influence of the successive members of the family who steered the company for more than a century. The two Michelin brothers were fertile inventors and marketers, applying their rubber knowledge to the emerging bicycle tire market. They introduced the first detachable and hence easily repairable bicycle tire, before beginning to produce tires for automobiles, trucks, and even airplanes. They manufactured airplanes during World War I and introduced the first trains on tires in 1929. To encourage mobility, they developed the first tourist guides and roadmaps, and they promoted road numbering and road signs. Edouard ran the company; his brother, André, was an astute commercial communicator and marketer. He launched and promoted bicycle and automobile races to demonstrate the superiority of the company's products. The Michelin Man logo, created in 1898, became universally recognized by motorists and, in 2000, a panel of professionals voted it the world's best logo.

Michelin's historical focus on innovation continued with the two brothers' successors within the family. Over time, they introduced most of the new modern developments in tires. In 1935, Michelin took over the automobile manufacturer Citroën and started developing the legendary Deux Chevaux which became a hit with young baby boomers after World War II. But what made Michelin the recognized innovation leader in the tire industry was the introduction of the revolutionary X radial casing tire in 1946. The concept brought such great benefits in terms of safety and tire life that, despite its higher cost, it was adopted by all tire manufacturers and became a world standard.

Building a Global Technology-intensive Company

The globalization and growth of the company from the post-World War II period until the late 1990s was led by François Michelin, Edouard's grandson. He was at the helm from 1955 to 1999 and passed the top job on to his own son, Edouard, who took over until the tragic accident that caused his death in 2006. From 2006 until 2012, Michel Rollier, another family member and Michelin's managing general partner, continued the family's historic focus on globalization and innovation, until he was replaced by Jean-Dominique Senard, the first non-family member CEO.

François Michelin was credited with refocusing the company on tires,2 keeping only the maps and guides business as part of the original family jewels. He acquired a number of competitors, including Uniroyal/Goodrich and a few smaller companies. He also initiated the company's globalization drive by establishing factories and subsidiaries in both North America and Latin America as well as in Asia. That move was continued and amplified under his son Edouard Michelin and Edouard's successor, Michel Rollier.

A fervent believer in technology, François set up the most advanced R&D and testing capability in the industry, which led to the development of tires for all kinds of applications, including Formula One cars, the space shuttle, and the Airbus A380 super jumbo. Michelin progressively applied its radial tire concept to all road and off-road vehicles as well as airplanes, and it developed a range of improved variants of that X tire casing. But François was not fully satisfied with incremental developments. So he urged his research department to pursue disruptive innovations.

Encouraged by their CEO, Michelin's engineers came up with several radically new ideas, some of which were cleverly engineered but ended up having limited application potential. Large amounts were invested in these developments, which caught the imagination of the company for a while but proved disappointing in terms of performance or costs, and thus had to be discontinued.

The most famous of these developments was PAX, an innovative but expensive tire and wheel system with an internal support ring that allowed drivers to continue their journey on a flat tire. The non-standard nature of the wheel, its assembly and specific service equipment, and the cost proved to be barriers to the generalization of the system.

Another disruptive manufacturing process innovation, called C3M, made it possible to build tires on a very compact machine from individual materials (rather than traditional pre-assembled components). It was not adopted on a large scale due to its disappointing cost/performance ratio. Its merit proved to be in stimulating manufacturing engineers to improve their traditional process to attain the performance level of the C3M, while continuing to use their current manufacturing set-up. Additionally, the bold approach for such a compact, modular process did lead to a breakthrough in manufacturing technology. This fundamental process technology now has numerous applications on new tire assembly machines, including high performance tire production.

Promoting Sustainable Mobility and Electric Propulsion

François Michelin was also a visionary regarding the future of mobility. As a company, Michelin always tried to contribute to vehicles' energy efficiency, but the concern for sustainable mobility really became part of its vision and mission in the 1990s. Management was aware that road transportation would have to dramatically change in terms of practices and technologies to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, primarily carbon dioxide (CO2). The contribution of tires to this overall CO2 and GHG reduction objective was significant. Indeed, tires have a major impact on vehicles' rolling resistance and thus directly on energy efficiency and emissions. This observation led Michelin's scientists and engineers to work persistently to reduce the rolling resistance of the company's tires. The Green X tire, introduced in 1992, was a significant advancement compared with Michelin's traditional radial tires. Improvements continued regularly over the years, leading in 2007 to the Energy Saver tire with its record-breaking low resistance.

In the truck category, the X One truck tire replaced standard dual tires with a single tire, providing significant improvements in rolling resistance and reductions in mass. Both the Energy Saver and the X One innovations have been recognized as industry transformers in a period when the contribution of tires to reductions in CO2 emissions is highly valued.

The launch of Challenge Bibendum in 1998, described as a “global clean vehicle and sustainable mobility forum,” was a tangible sign of the company's environmental commitment. Players from the automotive industry and the energy sector were invited to work on reconciling the automotive world and the environment by demonstrating new technologies and vehicle concepts for sustainable mobility.

Since electric vehicles (EVs) were expected to have lower mechanical resistance because of the removal of the internal combustion engine, the relative importance of tire rolling resistance in the total loss of energy would be significantly higher. Based on this consideration, Michelin's tire research and development organization had developed new low rolling resistance targets for EVs and a totally new concept tire for EVs.

Convinced that the future of the car industry would be strongly impacted by solutions in electric propulsion, in 1996 François Michelin decided to set up a small research center, called CDM (Conception-Development Michelin), near Fribourg in Switzerland. The center was totally devoted to the development of zero emission automotive technologies that had a real chance of being used in the future. This was one of François Michelin's last decisions before handing over to his son Edouard. Because of its different scope and time horizon, this small research center3 was deliberately set up some distance from Michelin's main tire technical center in France, which viewed it with a certain amount of skepticism.

Twelve years after its creation, Michelin's CDM research center had developed and successfully demonstrated the feasibility and performance of a broad range of innovative systems and components for electric and hybrid-electric vehicles, all covered by numerous patents. They included electric drives, fuel cells, and hydrogen storage systems.

Exploiting Opportunities in the Digital Era

In 1989, Michelin – world leader in road maps and tourism guides4 – pioneered the first computerized system5 allowing travelers to create roadmaps with detailed instructions. The company was therefore uniquely positioned to exploit opportunities in digital navigation systems. It started to work on its own GPS system, in competition with companies such as Garmin and TomTom. But in the early 2000s, management stopped all hardware developments, which were becoming extremely expensive, to focus instead on software. The company introduced a web-based navigation system – ViaMichelin – and is now developing GPS mapping and traffic information software to be embedded in high-end car navigation systems, a fast-growing segment. Michelin insiders believe that the company's relatively prudent move into digital navigation systems reflects (1) management's predominant focus on tires, and (2) a historical lack of management mechanism for venturing and new business development. Indeed, the creation of CDM and its focus on electric vehicles was the result of a personal visionary decision by François Michelin, not the outcome of a well thought through corporate development decision.

Refocusing on Incremental Innovation, Emerging Markets, and Profitability

In the 1990s and early 2000s, the whole organization was so R&D led that this created voids in other management areas, which did not help in addressing its competitiveness and financial health challenges. Besides, unsuccessful engineering-led developments affected the morale of R&D. They also created some skepticism in the organization and management toward radical R&D.

So, when he took over after Edouard Michelin's untimely death, Michel Rollier faced a threefold challenge. He felt that he needed (1) to better link the company's creative research group with the market; (2) to build manufacturing capacity in the emerging markets of Asia and Latin America; and (3) to rapidly improve the company's level of cost competitiveness and profitability.

In pursuit of renewed financial health for the company, Rollier refocused the organization on productivity and manufacturing rationalization. He was helped in this by Jean-Dominique Senard, one of his two managing partners6 in charge of finance and strategy.

Streamlining R&D

Having noticed that the company had not benefited enough from its disruptive innovations, Rollier passed a new message to staff: “Let's reorient Research so that it focuses on products that the market wants!” Didier Miraton – the second managing partner – acted as CTO in charge of Michelin's Technical Center. Together with his number 2, Terry Gettys, they launched an analysis of the company's past technological successes and failures. This assessment was used to introduce a number of changes to streamline and standardize the development process. These changes, introduced between 2007 and 2011, dealt with R&D ambition, speed, resources, and processes. They included:

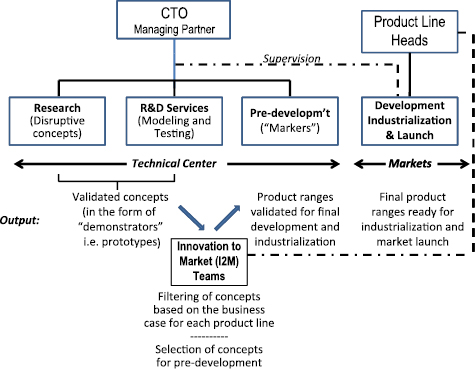

- Better recognition of the three distinct phases in product development: Advanced research to develop new concepts and new materials; pre-development – called markers in Michelin's R&D terminology – to elaborate some of the concepts from Research into producible tires; and development, industrialization, and commercialization.

- A more ambitious development program regarding the evolution of Michelin's future tire features. Given the increasing quality in the tire industry as a whole, Michelin had to perform 20 to 30% better on key tire features to gain significant differentiation and justify its price premium. But such changes could have a disruptive impact on manufacturing.

- A gate review system and a better way to link the research organization with the market through what was called an Innovation to Market (I2M) process. It was entrusted to the product line organizations, which were the ultimate receivers, developers, and industrializers of the new product concepts developed and prototyped by Research.

The new I2M approach was steered by the product line groups (passenger cars and light trucks; trucks; specialties, i.e. aircraft, earthmover, agricultural and motorcycle tires; and materials). It consisted of selecting from the research organization's output the most compatible and attractive concepts for the product lines on the basis of their business case. The pre-development group would then take the retained concepts and design the precursors of future product ranges to be developed and industrialized by the market organizations. The task of the I2M teams – a combination of technical, financial, and industrial people from the product line organizations – was therefore to establish a better link between Research and the market.

Figure 12.1 presents a simplified picture of Michelin's research, development, and industrialization structure (RD&I) toward the end of Rollier's tenure as CEO, and of its main output.

Figure 12.1: Michelin's RD&I Organization and Process

This refocusing on the market meant that the product line groups started to play a leading role in selecting and positioning key innovations in their new product portfolios. In a context of undercapacity in manufacturing and the need to reach a higher level of profitability, the product line groups started to apply stringent filters to radical ideas from Research. Thus, several of the latest disruptive developments conceived by the research organization were kept on hold due to a lack of resources for their market validation and industrialization. The bulk of Michelin's capital investments were indeed earmarked for new plant capacity in emerging markets like India, leaving radical concepts without adequate resources for rapid deployment.

This shift in emphasis, away from disruptive technology-pushed innovation toward market value-driven developments, and the resulting empowerment of the product line groups regarding new products, created some concerns within Research that had always benefited from special attention from the former CEOs François and Edouard Michelin.

Taking the Helm and Refocusing on Product and Market Leadership

Leveraging the Strengths of a Global Organization

A change of CEO – from Rollier to Senard – was announced in the spring of 2011 to become effective in May 2012. It was accompanied by the departure of the CTO and his replacement by his number 2 – Terry Gettys – an experienced American engineer who became executive vice president in charge of RD&I.

With a 14.6% share of the global market for tires, in second place behind Bridgestone, Michelin continued to vie for global market leadership and increased growth. By the end of 2012, the company had 113,500 employees; it had produced 166 million tires in 69 production facilities in 18 countries, and conducted marketing operations in more than 170 countries. Its 2012 consolidated net sales amounted to €21.5 billion, broken down as follows:

- Fifty-two percent came from passenger car and light truck tires and related distribution. The company was number 1 worldwide in both high-performance tires for cars and fuel-efficient tires. It was also strong in tire distribution thanks to its own networks of distributors – Euromaster in Europe and TCI in the USA. 7

- Thirty-one percent resulted from truck tires and related regrooving, retreading, and distribution. Michelin was number 1 in the world in radial truck tires and in retreading.

- Seventeen percent came from its specialty businesses. This category covered tires for the agricultural, two-wheel, off-road, and aerospace markets. It also included Michelin Travel Partner (the maps and guides business and the organizer of the ViaMichelin website and of the navigation software activity), as well as Michelin Lifestyle, its accessories business.

Michelin's strength was in the replacement tire market, where its reputation for quality allowed it to command a price premium of 5 to 10% over its competitors. Replacement sales represented close to 80% of volume in the market for passenger cars and light trucks and the same proportion in the truck market.

Keeping a Strong RD&I Organization

When Gettys took over the management of the RD&I organization, Michelin's technological advance over its competitors was based on a strong organization with over 6000 engineers, technicians, and testers. They spread across a network of laboratories and test centers in Europe, North America, and Asia (China, Thailand, and Japan). The group spent almost 3% of its sales on RD&I, with two primary objectives:

- To achieve the best performance balance for each type of tire use, in terms of safety, durability, fuel efficiency, and carbon emissions, as well as quietness and comfort.

- To reduce total lifetime cost of ownership for its customers.

Michelin prided itself on being the preferred supplier of tires for the motorsport industry and it had developed a special department specifically for that purpose. The company also collaborated closely with most of the world's vehicle manufacturers and bodywork designers, helping them in their innovation processes. Its partnership extended to the design and development of futuristic concept tires for cars to be exhibited in the main car shows around the world.

Building a New Top Management Team

Under Rollier, Michelin had been led by a triumvirate with a managing general partner (Rollier) as CEO and two managing partners. When he took over the CEO role, Senard did not retain the triumvirate. He reinforced the Group's former executive council, which had served as an advisory council to the managing partners, and turned it into a Comité Exécutif Groupe (CEG), with more accountability when it came to steering the company's performance. The CEG included 11 members:

- the four product line directors;

- the director of all the geographic zones;

- the director of RD&I;

- the director of commercial performance; and

- four corporate directors (in charge of finance; corporate communications and brands; personnel; and corporate development).

An “extended CEG” was created including functions such as individual geographic zone directors, heads of research, strategic anticipation and sustainable development, purchasing, and a few other key central functions.

Refocusing on Product Leadership

Having made a lot of progress on productivity and costs and expanded its capacity in emerging markets, Michelin was now in the perfect position to reinforce and accelerate its innovation focus. Senard fully appreciated the challenges the company would have to face and the role that effective innovations would need to play.

Michelin was in danger of seeing its superiority in tire performance threatened by competitors. To keep its price premium in the market, the company had to boost superior product performance in areas most valued by customers. Since the premium segment of the tire market was limited in size, Michelin also needed to pursue cost-effective innovations and leverage them in broad market segments under its multiple brands.

Senard was also concerned by what he saw as the danger of loss of innovation spirit in his business organization. The company's product line management teams were busy with much-needed capacity building programs and jockeying for position in the market with their leading competitors. Radical innovation was no longer their first priority. As for Michelin's scientists and engineers, they remained uncertain about the best way to get the market organizations to adopt their new product concepts.

Finally, Senard was convinced that his management team, by being focused on tires, was missing growth opportunities in adjacent or totally new product or service areas. Based on these considerations, Senard set the objective to reinforce Michelin's product and market leadership with a rapid action plan.

Addressing the Product Leadership Challenge through a Dedicated Project Group

In June 2011, Senard held a series of meetings with Gettys, the new head of the RD&I organization, on how to accelerate the time to market for key innovations. Gettys immediately started a work group to evaluate the existing company-wide innovation process and identify its strengths and deficiencies. He also consulted Pascal Thibault, head of organization, consulting, and transformation within Michelin's HR department, to explore how to boost innovation in the company.

The shift in focus from managing research to managing the whole innovation process came up naturally and it was quickly endorsed by Senard. Gettys and Thibault subsequently suggested creating a small task group – called the Lead project group – to address the challenge, under Gettys' leadership.

- their personal experience and legitimacy with regard to innovation; and

- their mental openness and preparedness to challenge the status quo and propose radical solutions.

Ultimately, the Lead group was set up with members from different areas, as follows:

- the head of Research, the department traditionally responsible for inventing new concepts;

- the two leaders of the US and Japanese research centers;

- the head of the manufacturing process research group;

- a marketing specialist from the passenger car product line, experienced in the front end of innovation;

- a former boss of the agricultural product line, now responsible for Michelin Solutions, the company's new service arm;

- the head of the strategic anticipation and sustainable development group; and

- two “guests” – a consultant and a former Michelin senior manager who had assumed responsibility for the company's sports association.8

The Lead project group was up and running by July 2011. Senard insisted that it had to come up with recommendations to Rollier and Senard by early November. Quickly, Thibault realized that what was at stake was an entirely new innovation governance model and process for Michelin. The limited time frame available for formulating concrete recommendations meant that the group would need to be coached by another external consultant who specialized in helping teams in the conception and implementation of radical change.

With the help of their consultant, the Lead team organized two intense workshops spread over two months. Each workshop was attended by about 20 or 30 participants and preparation involved a number of meetings in small groups. The first workshop focused on a diagnostic of the situation and the second on formulating a broad set of recommendations. The final report, “Innovation Performance and Dynamics,” including what they called a new innovation governance ecosystem – was presented in early November 2011 and approved.

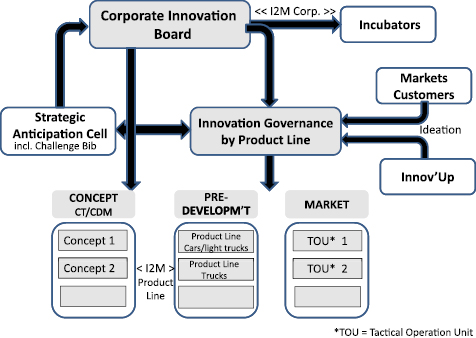

The architecture of the new governance model is shown in Figure 12.2.

Figure 12.2: Michelin's New Innovation Governance Ecosystem

The Lead team's conclusions were very detailed and contained preliminary missions for each part of the innovation governance ecosystem, together with tentative suggestions of people to be in charge. It covered the following tasks:

- Assigning responsibility for the CDM center – the Swiss advanced research group which developed systems for electric cars – to the worldwide research director.

- Revisiting and improving the Innovation to Market (I2M) process that links concept research with the product development organization.

- Reviewing the way the research organization works, with the objective of broadening its scope.

- Improving the identification and inclusion of previously unarticulated customer needs in product specifications.

- Broadening the collection of ideas to the entire Michelin organization and not only the RD&I group.

- Reinforcing and structuring Michelin's ability to track and exploit weak signals announcing important future developments.

- Building an incubator for innovations offering potential new business opportunities that do not fall directly within the domains covered by the tire product lines.

Setting Up a Corporate Innovation Board (CIB)

The Lead project team's main recommendation, which was enthusiastically endorsed by Senard, was to establish a high-level corporate innovation board (CIB). This board would take strategic decisions on innovation priorities and orchestrate company-wide efforts to boost innovation performance. This new mechanism de facto replaced the functional roles and organizations that had hitherto tried to pilot innovation.

Staffing the CIB

Senard welcomed the Lead project team's proposal that he should formally chair the CIB, with Gettys serving as “animator.” The membership of the CIB reflected the strategic importance of the decisions to be made, because the CIB would deal not only with the process of innovation but also with the content of the company's innovation portfolio.

Besides the CEO (Senard) and the executive vice president RD&I (Gettys), the CIB included several members of the Comité Exécutif Groupe, namely the four product line heads. It also included the director of commerce, the head of corporate development, and the head of strategic anticipation and sustainable development, acting as CIB secretary. Finally, it was decided that two external, non-Michelin executives would be invited to participate – a French executive bringing competencies in services innovations, and a highly reputed innovation management professor from India.

Operating the CIB

The first CIB meeting took place in March 2012, a mere four months after the Lead project group presented its recommendations to the Michelin partners. At that first meeting, Senard and Gettys, as chairman and animator respectively of the CIB, reminded its members of their two missions to:

- take strategic decisions on needs and research priorities; and

- manage the dynamics of innovation company-wide.

By March 2013, the CIB had already met four times and it had reached its cruising speed of three meetings per year, in March, June, and October. Gettys now believes that he needs to introduce a more regular scheduling of topics to optimize the timing.

To ensure that all CIB members are clear about the points that have been discussed and decided, each meeting ends with a formal reading of the decisions. These decisions are collectively reformulated to avoid misunderstandings and surprises when members go back to their business.

The main strategic role of the CIB is now to steer the development process, particularly the front end, by determining the strategic objectives and priorities of the research group. Research will no longer work in a pure technology push mode; it will follow the priorities defined by the CIB on the basis of their market potential. The CIB has thus become a cross-functional locus for identifying and enforcing ambition-driven product/market objectives. It will be helped in its mission by the strategic anticipation unit, which is expected to contribute insight and foresight.

Management recognizes, though, that decisions on new products made in the CIB need to strike a balance between satisfying the immediate, incremental needs of the product lines and being ready for the future by funding more radical concepts. Given the presence of the four product line heads on the CIB, who are evaluated annually on sales and profits, such a balance might be difficult to strike … unless the other more neutral members, and particularly the CIB chairman and the animator, weigh in heavily to defend the more radical projects.

In its first year of operation, the CIB established two new domains that had not previously been treated as priorities by Research. This demonstrated the effectiveness of the broad CIB membership in identifying significant societal and market trends in order to anticipate new technology domains needed for future products and services.

Setting Up Other Elements of the Innovation Ecosystem

Encouraging a Bottom-up Ideation Process

The Lead project team had recommended the promotion of two sources of new bottom-up ideas. The first one, which still needs to be further developed and implemented, is the search for unarticulated customer and market needs.

The second, called Innov'Up, entails the implementation of a formal bottom-up ideation process to act as a strong counterbalance to the top-down impetus embedded in the CIB. A leader has been appointed and experiments have already been launched in the form of “challenges.” Indeed, to make this bottom-up quest for ideas concrete and mobilize the organization, a number of questions have been asked to the entire Michelin Group, which should enable people to work together on these challenges and recommend responses. These challenges have already led to promising results.

The use of social media is also being promoted to allow people worldwide to react to and enrich the ideas generated. The task of filtering ideas has been entrusted to the incubator office (see below), and the CIB is determined to act on the best ideas generated.

Putting New Business Building Activities in Incubators under the CIB Spotlight

Before the creation of the CIB, Senard had already promoted a separate service business, Michelin Solutions, with the objective of developing and selling a broad range of service offerings for cars and truck fleets, later to be extended to fleets of aircraft and off-road vehicles. This business was staffed by some of the company's best marketing minds, who were encouraged to work with a broad range of hardware, software, industrial, IT, and financial “complementors” to offer comprehensive and integrated fleet transportation and mobility solutions.

As a way of managing these new activities – hardware, systems, software, and services – that do not fit with Michelin's existing product lines, the incubator concept was adopted. The most obvious incubator candidates were those technologies that had been developed to a good maturity level, yet fell outside the priority scope of the tire product lines. Everyone at Michelin is aware that the outlook for these activities is uncertain, given that they resulted from a pure “inside-out” perspective. They were not products requested by the market. They ought to be complemented by other “outside-in” business ideas, emanating from a systematic search for unarticulated or latent customer needs. The two ideation processes mentioned above and put in place as part of Michelin's innovation governance ecosystem (refer to Figure 12.2) will undoubtedly contribute such ideas once they are fully operational.

The incubators created by the CIB are under the supervision of an incubator office headed by an entrepreneurial manager. His mission is fourfold:

- Put in place a process and tools to evaluate, screen, and rank ideas coming from both the markets/customers and internal sources – through the Innov'Up process – based on their attractiveness for Michelin and their feasibility/risk.

- Develop and implement a formal venturing process with specific development phases, linked with progressive investment gates, and a way to reduce technical and market uncertainties.

- Coach these new project teams as they proceed, particularly in their partnership discussions and business development efforts.

- Recommend to the CIB, which will remain the main decision body, the new projects worth incubating, as well as those whose outlook does not justify continuing investment and hence need to be stopped.

The CIB will maintain overall supervision of these new businesses and will be ready to create an operating company for them if their market outlook is positive and they are viable from a business point of view.

One of the missions of these incubators is to change Michelin's attitude to innovation. Traditionally, market failures on radical innovation concepts were regarded as abnormalities, and they remained tainted with frustration. Nobody talked about them. With the incubator concept, management is passing a very different message, i.e. not all projects are expected to lead to success. In a way, incubators should rid Michelin of its guilt feelings about high-risk innovations and they are expected to liberate the generation of new ideas.

But Senard and his CIB colleagues are aware that the profiles required to lead and work on incubating projects – intrapreneurs and risk takers – may not be widely available within the company. Michelin has traditionally sought solid professionals, focused on quality and operational performance, to progress its mature tire business, rather than explorers and go-getters. These profiles are critical for successive incubators and in some cases may have to be sourced outside the company.

Cascading the CIB Idea to the Product Line Level

To manage innovation at the product line level, two parallel organizational mechanisms were created: the Passenger Car Innovation Committee and the Trucks Innovation Committee. These committees are headed by the product line director and key staff responsible for marketing, technical development, industrial development and quality, plus the heads of the corporate research and pre-development groups. Their major role is to steer the I2M filtering process, i.e. to select the major innovations from Research to be introduced in their product line, work with pre-development to build a strategy and business case, and then steer the industrialization phase to go to market as fast as possible. Industrialization and commercialization are handled at the regional level by tactical operational units which have the same product line functions but in a given market area, like North America or Asia.

Anticipating the Next Steps

Members of the CIB appreciate that they have a long road ahead to overcome some of the limitations of their new innovation governance system and to extend and complement it with new features.

Correcting Current Deficiencies

Three potential challenges have been identified and are being remedied.

The first one has to do with the risk of excessive short-termism. This fear is linked to the fact that the product lines currently strongly influence the broad orientation of research, i.e. the themes to be explored and decisions on product priorities. This could reinforce the danger of developing a silo mentality in which each product line narrowly concentrates on its immediate, incremental development objectives. At the CIB meetings, the members must represent the overall best interests of the company, with a strong priority on getting the most impactful innovations to market rapidly. The issue of whether disruptive tire concepts, once invented and validated, can be handled within the current approach – i.e. within the I2M process – or whether they need to be nursed by a specially funded tire incubator has not yet been evaluated.

The second challenge is linked to the first one. Product line heads, particularly of the leading ones, i.e. passenger cars and trucks, may be tempted to pull too many research and pre-development resources toward their own domain. As head of the RD&I organization, Gettys feels that his role is to stop excessive requests by these product lines to the detriment of some of the smaller, less vocal ones. He is helped in this task by the fact that the CIB includes a number of leaders with a broad corporate perspective, e.g. the heads of commerce, corporate development, and the strategic anticipation unit, as well as the two “outsiders.” Besides, the product line heads have been chosen for their ability to act for the good of the company, not only of their business.

The third challenge is that the I2M process – which is in place to validate the concepts developed by Research and filter them on behalf of individual product lines – is perceived to be too slow. Indeed, it generally involves a number of time-consuming activities, such as market research to identify potential customer targets and price ranges. For some innovations it also includes joint testing of demonstrators (prototypes developed by Research) with OEM customers or fleet operators to check how well they are accepted. These activities can take 12 to 18 months of work before go/no-go decisions can be made. The solution that has been adopted is to start this I2M investigation process six months before the demonstrators are totally validated. But Gettys believes that the overall lead time is still too long and will have to be shortened in the future.

Extending the Scope of the CIB

After only four meetings and a number of substantive changes in strategy and process, CIB members know that they must extend the scope of their innovation governance activities.

Setting Up Innovation Indicators

One of the first tasks on Gettys' to-do list is to propose a number of innovation-related indicators. Michelin has a disciplined culture, and when people are given indicators, for example on safety, they tend to act effectively to improve the factors being measured, in this case the rate of accidents. Product line heads each have 15 indicators on their scorecard and every organizational entity has a scorecard, so applying a measuring philosophy to innovation input and output would not be difficult. But Gettys is concerned not to overdo it and to add only the most important indicators to the current pyramids.

Promoting Innovation Excellence

This focus on innovation performance indicators and on benchmarking, according to Gettys, should be entrusted to a new corporate function which aids the CIB by tracking innovation performance. This function is viewed as a necessary resource to constantly assess the dynamics of innovation, i.e. corporate-wide innovation excellence, beyond RD&I activities.

Looking for Business Model Innovations

Another concern, shared by most members of the CIB, is to broaden the scope of innovation to cover more than technologies and products, for example toward new business models. Michelin has traditionally innovated in its revenue model to take full advantage of the superiority of its radial tires in terms of longevity and retreadability. For example, instead of selling truck tires or off-road equipment tires to fleet operators, the company has pioneered the concept of invoicing operators on the basis of ton-kilometers. Similarly, its aircraft unit invoices airlines on the number of take-offs and landings accomplished with a given set of tires. But these revenue model innovations are already proven, and the company will need to establish a process to systematically pursue new business model innovations.

Searching for Innovation Opportunities in Internal Operations

Senard is interested in applying innovation concepts to the field of services, as exemplified by his strong involvement in Michelin Solutions, the company's full service arm for private customers and fleet operators. But he is also quite keen to introduce innovative new concepts in the company's internal service functions. One of his most visible moves was to create Michelin Business Services, an internal department for efficiently consolidating all kinds of administrative and logistics functions. This, he believes, should bring efficiency gains via highly focused centers of excellence that support a number of company functions. Indeed, Michelin's organizational entities around the world are currently run independently and have their own administrative infrastructure, which leads to a number of cost redundancies that could be eliminated.

Building a True Culture of Innovation Company-wide

Finally, Senard and his CIB colleagues are aware that the company's culture may have to evolve if innovation is going to extend beyond RD&I specialists to reach all corners of the organization. This may require a major change program to encourage attitudes of openness, initiative, collaboration, risk taking, and entrepreneurship, among other qualities.

One of the guidelines for such a change program might be the Michelin Performance and Responsibility (PRM) approach, which was launched in 2002 to help everyone in the Group remain focused on the long-term consequences of their decisions. As indicated on the website: “In addition to expressing Michelin's sustainable development commitment, PRM also shows that achieving performance and responsibility is the best way to move Michelin forward. In 2012, PRM's 10-year anniversary was widely celebrated across the Group.” The PRM approach has stressed and measured a number of the company's achievements in areas like sustainable development, customer orientation, and corporate social responsibility. As the highest-ranking champion of the PRM philosophy, Senard may be tempted to leverage PRM's traction by finding a way to integrate an innovation agenda into the PRM list of great internal and external causes.

Going Public and Maintaining the Effort

After testing the new governance model and checking that it helped to address Michelin's innovation challenges effectively, Senard felt the need to inform the Michelin organization more broadly. He communicated the news about the new innovation governance model at his first general assembly of shareholders as CEO. The participants had not expected Michelin's management to tackle the company's challenges through innovation. They were thrilled to learn that innovation was, once again, at the center of management's priorities.

But Senard and his CIB colleagues know that they now have to mobilize the entire organization behind their new innovation agenda. The first information round covered the 90 or so most senior managers. The next step was to reach 3000 company managers around the world in a conference called The International Bib Forum. The conference, which was held in Paris, allowed Michelin's executive committee to present the company's new innovation governance ecosystem. But it also stressed that innovation, in addition to its strong top-down dimension, requires a massive bottom-up effort to mobilize the entire organization in the quest for market insights and innovative ideas. Management expects that everyone in that forum will have understood that he/she can participate in this effort.

At that conference, besides announcing that management would organize a corporate innovation award, Senard publicly stressed that his personal commitment at the head of the CIB is not a temporary phenomenon. It is there to stay … because innovation never ends!

Notes

1 One of the two French entrepreneurs, Edouard Daubrée, married the niece of Scottish scientist Charles Macintosh, who discovered that rubber was soluble in benzene.

2 Michelin sold Citroën to the Peugeot Group in 1974 in order to concentrate on its core tire business. Later it sold all its non-tire activities (suspensions, wheels, batteries, etc.) except the maps and guides business.

3 In 2010, it employed 70 or so engineers and technicians.

4 The company sold 10 million maps and guides in 2011.

5 The 3615 Michelin system was made available on Minitel, a French Videotex online service accessible via telephone lines (it is considered one of the world's most successful pre-World Wide Web online services).

6 Michelin is incorporated as a partnership limited by shares. It is led by a managing general partner (CEO), assisted if needed by one or two managing partners.

7 Michelin had taken over some of its European distributors and created a broad Europe-wide network of tire service stations called Euromaster. Its agencies sold competitive products in addition to Michelin tires.

8 Since its creation, Michelin has always believed in the values of sport as a management philosophy. The company has been a strong promoter of sports in its organization, and the sports association it sponsors in Clermont-Ferrand is one of Europe's largest and most dynamic sports clubs.