CHAPTER 4

Why Focus on Innovation Governance Models?

Companies that have a commitment to ongoing innovation also have, whether explicit or implicit, a governance model by which they allocate authority and responsibility for innovation within the organization. Our research has shown that even though they may not talk about “innovation governance,” most companies manage innovation according to a governance model that senior managers can describe. The mission to promote and oversee innovation might be entrusted to a particular person – who may or may not be fully dedicated to the task – or it can be taken on by a group of managers working together in the context of different types of organizational mechanisms. Our respondents' experience also shows that these models tend to evolve over time.

The evolution of governance models may reflect changes in innovation processes, for example the maturation of innovation practices and the shift from “developing products” to “innovation.” The evolution may also be justified by changes in the innovation context, such as the rise of global innovation, digitization and the internet, and partnering or “open innovation.” There may also be changes in staffing and structure, often linked to the appointment of a new CEO or CTO. Some of these evolutions represent management's desire for a more effective innovation process or a broader or different innovation focus. Others simply reflect a change in management philosophy or personal commitment at the top.

But one thing stands out – few companies we know seem to have adopted a systematic approach to identifying and comparing possible models before choosing one. And equally few are able to review possible models when they feel that their existing model needs improvement. In fact, often senior managers' descriptions of existing innovation governance practices are basic and incomplete. In our survey, several managers in the same company described the company's governance model differently. There is often a lack of clarity and comprehensiveness in the way governance is understood by top management. We feel therefore that it is critically important to specify and evaluate the range of possible models (1) so that companies can be more reflective and explicit in their choice of governance model, and (2) so that they can choose the ones that best fit their current conditions and aspirations and be able to keep improving them.

Why Do Companies Need an Innovation Governance Model?

Innovation is a complex, company-wide venture carried out by people who assume very different roles and responsibilities within the company. Although they belong to different groups and functions, which are typically committed to different goals, their efforts must be aligned in order for innovation to be successful. They must also be aligned with top management's goals and strategies. Top management must decide who is going to be responsible at the highest level for innovation in the company and who will play a supporting role. It is this combination of primary and supporting responsibilities for innovation to achieve critical alignment that we refer to as a “governance model.”

Like other complex, company-wide issues that need a proper governance system – including quality management and commitment to environmental sustainability – innovation must have a governance system that enables the adjudication of disputes, the allocation of resources, the alignment of strategies, and so on.

Corporate governance is most usually associated with the board's role – the board has a clear and articulated responsibility to oversee the actions and strategies of the company and to ensure that these align with both legal directives and the interests of stakeholders. But, as we saw in Chapter 2, although in some companies the board has an explicit interest in innovation, in most companies innovation is left to the employees, and the board is merely informed of strategy and outcomes. We hope it will become evident, in this chapter and in subsequent chapters, that the board should play an important and supportive role in innovation and innovation governance. It should, at least, be aware of the company's governance model. This does not mean that the board should meddle or try to take the place of innovation-focused employees!

What are the Key Elements of an Innovation Governance Model?

At least three key tasks must be dealt with when implementing an innovation governance model:

- Assigning primary responsibility.

- Defining the scope and level of responsibilities.

- Planning the support mechanisms.

Here again, we address the need to make governance explicit. As we have seen, often people do not know for sure who holds primary responsibility for innovation. Is it the CTO or the CMO? What is the role of the CEO? How empowered is the innovation steering group? The duties of those who are responsible for governance are far too complex and important to leave these questions unanswered.

Defining the scope and level of responsibilities is also a key task; and of course, as management deals honestly and explicitly with these two tasks, each will help to shed light on the other. If the two tasks are well executed, addressing the third will not be so hard. This last task requires a level of understanding of innovation best practices, and the details can be entrusted to those whose expertise is in that realm.

Assigning Primary Responsibility

The main element of an innovation governance model is assigning primary responsibility for innovation in the company. In some companies it is obvious who is responsible. For example, in Chapter 8 we will see that at Corning responsibility for front-end or radical innovation is assigned to the Corporate Technology Council (CTC), while responsibility for getting innovations to market rests with the Growth Execution Council (GEC).

In many companies, however, it is not so clear who is responsible. Our experience is that descriptions of who has primary responsibility for innovation tend to be basic and incomplete. When managers in the same company describe its governance model differently, this highlights a lack of clarity and comprehensiveness in the way governance is understood.

Duties that we include under primary responsibilities are often split or shared: for example, in companies like Nestlé, the head of all strategic business units may be responsible for defining where and on what the company should look for innovation, while the CTO defines the how. This kind of teaming can succeed when the pair works well together; if it does not, this can seriously disrupt the organization's chances of articulating and pursuing a coherent innovation strategy.

If primary responsibility for innovation governance is not assigned in the context of a holistic view of innovation, the assigned roles are likely to be at odds with each other. For example, one company adopted the mission of “growing by innovation” and appointed a director of innovation, but its annual portfolio assessment set its sights on projects that would have short-term payback. As a result, although the explicit assignment held the promise of setting and meeting innovation targets (and, in fact, under this director's leadership identified a number of promising opportunities), the tacit commitment of the company's leadership to conservative investment stymied any positive results that might have emerged from creating the director of innovation position.

Defining the Scope and Level of Responsibilities

The second element is the scope of innovation responsibility and the level of empowerment of those who fill innovation governance roles. This aspect of innovation governance also presents challenges. Most positions within a company are limited to particular functions and/or divisions. A key feature of successful innovation is that it crosses boundaries. Those who are assigned leadership roles in governing innovation must, likewise, cross boundaries. This calls for clear assignment of roles and empowerment that might upset the usual ways that business is done.

Explicit allocation of responsibilities requires corporate alignment on what is necessary for successful innovation. For example, what processes and subprocesses are essential? How will their effectiveness be judged? Who will be responsible for launching improvement initiatives? A reflection of the complexity of these questions is the degree to which leading innovation companies have gained value from the dialogues of the International Association for Product Development (IAPD) and other such peer groups. Many companies now have specific roles for process architects, or process owners, but the scope of innovation goes way beyond the design, implementation, and continuous improvement of processes. Companies need to make these questions clear and create alignment to ensure successful governance.

Planning the Support Mechanisms

The third element is the creation and implementation of supporting organizational mechanisms to manage specific aspects of innovation, or to manage innovation in specific parts of the company. By its very nature, innovation demands that innovators have the freedom to experiment, to change direction and to break with old habits and patterns. This is why some people raise their eyebrows when they hear the phrase “innovation governance.” Some companies, usually those with powerful innovator CEOs (who are often also founders), can be run rather like dictatorships. At Polaroid, innovation came from the top, from Edwin Land. His chief support mechanism was to start several teams working on an idea. He could then choose the inventions and designs that best matched his idea. The rest of the company was set up to carry out the required actions to bring the idea to market.

More “democratic” companies, where innovation is bottom up or a combination of top down and bottom up, require a more subtle governance model. They need one that will enable freedom in the pursuit of novelty and change but at the same time reduce the anarchy and confusion that ensues when no one “knows the rules,” when the rules conflict, and when those who make the rules are not in alignment, or sometimes even in communication, with one another.

In this context, IBM's characterization of its approach to innovation as “managed anarchy” seems to be right on target. As we will see in more detail in Chapter 7, Sam Palmisano, like many successful CEO innovation leaders, was a great spokesman for innovation, not limiting his passion to within the company but sharing it with other organizations that might help spread the word among innovation partners. He also found effective ways of conveying his message on innovation to the whole company using social media and allowing everyone to participate. Although IBM's governance model is basically top down, the company also has a carefully designed and regularly updated set of processes for innovation that specify who does what. We might conclude that, at IBM, innovation is inspired from above, spread wide through intranet connections, and kept on track by precise and well-implemented processes.

The Governance System and an Explicit Constitution

While the kinds of governance mechanisms described above work well in some companies, there is often an element of “magic” – something that is hard to explain, even hard to understand, and often dependent on particular people (e.g. Jobs at Apple). A successful innovator, in order to tip the scales toward long-term success, needs to allocate innovation responsibilities and define the nature and the boundaries of those responsibilities. Otherwise, as happens too often, decisions made by one person or group may be undermined by another, and often there is no recourse, no system of adjudication for settling disputes. One of the obvious causes of innovation failure is a lack of alignment of decision makers – people with the authority to set limits, give the go-ahead to projects, and identify the markets, technologies, or potential partners that innovators should be exploring. One decision maker gives the go-ahead; the other fails to resource the project. One decision maker points the innovators toward a particular market; the other – after considerable resources have been spent – declines to allow any innovation in that arena. And so forth.

In our research, it became evident that although our respondents were able to identify a governance model that had been implemented in their company, only rarely could they explicitly state the nature and boundaries of the allocated responsibilities. For example, a respondent might state that the CTO is in charge of innovation but not be able to specify what this means in any detail. Does the CTO determine levels of acceptable risk for innovation projects? Does he/she determine the balance of the innovation portfolio? If the company uses a phase/review process to take projects from early approval to commercialization, what is the exact task of the reviewers and what is their relationship to the CTO? These are important questions, and in many companies – though certainly not all – there are no explicit answers to them, and this lack of clarity is a major cause of waste, frustration, and failure.

Accomplishing the three difficult tasks that we have described above allows a company to move from an intuitive approach to innovation to one that is clearly communicated and clearly understood. And, perhaps equally importantly, the accomplishment of these tasks positions the company on a path to continuous improvement. Clarity about its own approach will help it to overcome the typical blind spots when it comes to seeing and appreciating what is new – be these opportunities or challenges. And such clarity can pave the way for developing what might be called an innovation governance constitution.

In Chapter 1 we suggested that a form of constitution is necessary for proper innovation governance in order to provide a frame for innovation activities that cut across organizational units, as well as to curb individual and functional interests in favor of corporate interests. The innovation governance constitution should include the three tasks outlined above, as well as:

- Specifying rules of legitimacy, which define who owns what, who does what, who is responsible for what, and what legitimizes these responsibilities.

- Identifying desired targets regarding growth through innovation and use of resources.

- Defining methods for resolving conflict, especially when innovation activities conflict with accepted line responsibilities and activities.

- Stating how the company will protect stakeholder interests, both internal (e.g. employees) and external (customers as well as other beneficiaries and/or potential victims).

Few companies have an explicit constitution. One of our purposes in this book is to elucidate the models that companies are using so that the value and the practicality of addressing these kinds of issues can be apparent.

What Models Do Companies Use?

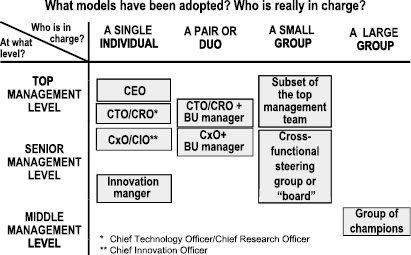

Our research has identified nine models that companies use today (10 if one includes the option of no one being in charge). These models range from having single individuals in charge to duos or groups, and they range from top to senior to middle management. The models in place in a company are often influenced by the company's history and culture and they reflect the choices management must make when allocating responsibilities for innovation.

The first choice relates to the type and number of bearers of that responsibility. Will innovation oversight be entrusted to a single manager or leader? Will that person be fully dedicated to the task or not? Will it be given to a duo of managers or leaders or to a small group of leaders? Or will it be distributed among a larger group of managers?

The second choice deals with the management level of the appointed innovation heads and their reporting relationships. Should the jobs be filled by top managers reporting directly to the CEO or to the executive group? Should they involve less senior or even middle managers reporting to a lower level of management?

When they are combined, these two choices determine nine different models of governance, as illustrated in Figure 4.1. In practice, large companies tend to use several models to steer innovation.

Figure 4.1: Typology of Governance Models

Multi-business corporations may not steer innovation centrally but rather let each business group or division choose its own model. For example, Elanco, the veterinarian business within Eli Lilly, has developed its own model of innovation governance. Although Eli Lilly's governance model is a high-level cross-functional steering group, Elanco's model places the main responsibility with the division's president and teams of innovation champions.

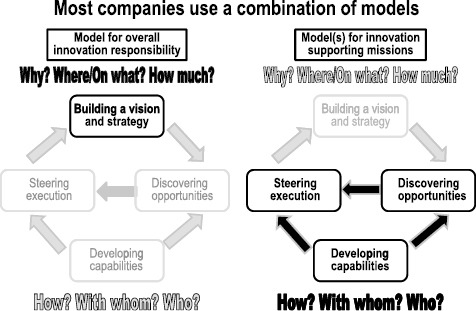

But even if companies have adopted a single corporate approach to innovation, they may opt for several models, for example a general model to promote and steer innovation overall, and one or several supporting models or mechanisms to leverage the first one and deal with specific missions. The overall model typically deals with the three content questions (why, where, and how much), while the supporting models tend to focus on the three process questions (how, with whom, and who). Figure 4.2 illustrates the different focus of these two types of models.

Figure 4.2: A Different Focus for Each Type of Model

Models Dealing with the Why, Where, and How Much Questions

These important questions are the three keys to innovation strategy. In short they should be resolved by top management and the board should also play a role in addressing them. If overall innovation responsibility has been entrusted to people in a lower hierarchical level than top management, then they ought to make their own assumptions regarding the answers to these questions and propose them to top management for approval (or modification).

The answers to the second and third questions (where and how much) will obviously be influenced by management's answer to the first. Just as innovation models have moved over the past couple of decades from an emphasis on developing new products to a much broader scope that includes, for example, business model innovation, so the question of where the company will look for innovation has broadened. Companies now look to markets and capabilities that would have seemed way out of their realm of interest in previous decades. The question of where needs to be addressed in the context of research and understanding of markets and of competencies and capabilities, and it should be seen as a moving target. Those tasked with answering this question need to be sure that the company's innovation system is up to date in this respect.

The last question, how much, is probably – even more than the other two – one that only top management can address. If it is not well handled, it can cause much undue waste and leads not only to great inefficiency but also to unnecessary discouragement of innovators. How much is top management prepared to spend on innovation? How will it define innovation – as limited to breakthrough new projects, or encompassing all of the ways in which the company changes its value proposition? Or something in between? The answer to how much needs to be considered not only in terms of percentages or funds but also in terms of on what, and the decision-making processes need to be aligned with top management's position on this topic.

Models Dealing with the How, With Whom, and Who Questions

The second set of questions is more in the domain of process and is often guided by what we call supporting mechanisms. There may be different types of supporting mechanisms for different processes, which is why most companies use a range of supporting mechanisms. For example, the supporting mechanism for idea management will often be different from that for portfolio management or project review and control. Addressing these questions builds the company's capability for innovation and steers the actual project work that is necessary to take opportunities from possibility to reality. Of course, this aspect of governance flourishes when the first three questions have been dealt with effectively and is virtually crippled when they have not been. Many companies have had “process owners” or “process architects” for many years now, whose responsibility is to keep these processes working, to upgrade them, and to identify new ones which might add to innovation effectiveness.

Companies have always relied on external partners or suppliers to add to their own capabilities. In the past, this was most frequently limited to suppliers who could provide the required elements of a product – for example, a company might contract with a supplier to make an electronic part that the company did not have the know-how to produce. This is why the with whom question could be delegated to functions and people close to operations. Then, the theory of supplier relationships was largely based on how to get the best deal from the supplier. But today, the question with whom has become an important and strategic aspect of open innovation as companies work with partners around the world to expand capabilities and market access. And this is why this question – at least in terms of policy – has moved back to the top management level.

The question of who – who in the company should be involved in innovation – also has an impact requiring some top management involvement, inasmuch as it can present problems and issues that can stall and disrupt innovation activities. The answer to who should be involved is, in our opinion, anyone whose talents and interests might be helpful in creating value – for the customer and for the company. Of course we do not mean that everyone should swarm to every project that is of interest – part of the job of innovation governance is to protect innovators from the frequent tendency to assign too many projects and stretch resources beyond the breaking point. However, it has become increasingly apparent that when innovation is carried out in functional silos, the company's ability to succeed is diminished. Governance of the question “Who will participate in innovation?” needs to ensure that functional boundaries do not prevent collaboration across organizational units.

In summary, however the responsibilities for governing innovation are deployed – whether there is a single model in use or responsibilities are allocated to two or more people or groups – governance must take into consideration these six questions. Innovation is a systemic enterprise and if the answer to any of these questions is missing or incomplete the whole structure will suffer.

The Nine Governance Models

- Model 1: The top management team (or a subset of that team) as a group. In this model – which seems to be the most widely used – members of the C-suite share the duties of governance, although most often membership is limited to those who are directly involved with innovation – e.g. business leaders plus marketing and R&D.

- Model 2: The CEO or, in multi-business corporations, a group/division president. When the CEO is in ultimate charge of innovation, the message that innovation is a top priority for the company is usually loud and clear. Many get that message out beyond the limits of the company. Steve Jobs, Jeff Bezos, A.G. Lafley, and Akio Toyoda, among others, have all contributed to the fact that the whole world is more engaged in innovation – not just their companies.

- Model 3: The high-level, cross-functional innovation steering group or board. Members of such steering groups or boards are chosen based on functional responsibilities and frequently also on their personal interest in and commitment to innovation. Often a CTO or CRO chairs the group, but other members may span a couple of levels under the executive committee.

- Model 4: The CTO or CRO as the ultimate innovation champion. This model is most usually employed in companies with a strong technology and/or engineering tradition. The CTO/CRO model focuses on the content of innovation, i.e. on the promotion of technology-based initiatives, and the CTO or CRO is rarely involved in the non-technical aspects of innovation.

- Models 5 and 6: The dedicated innovation manager or chief innovation officer. The difference between these models and the CTO/CRO model is that responsibility for innovation is entrusted to a single, dedicated manager, not to a busy CTO/CRO with operational duties. In this model the innovation manager's focus is more on the process than the content side and he/she is usually responsible for tracking innovation success and identifying and sharing best practices.

- Model 7: A group of innovation champions. This model is more frequently found in a supporting model role than as a primary governance model. Typically, champions are innovation enthusiasts, sometimes referred to as “intrapreneurs.” In some companies their focus is mostly on content, i.e. specific projects. In others it is more on the process side as they work to share innovation practices and experiences.

- Models 8 and 9: The duo or the complementary two-person team. The duo might be a CTO who shares innovation responsibility with a business unit manager, a functional manager, or a CXO. Few companies use either of these models, but they do exist.

An additional model is when no one is in charge. In some companies innovation is so much part of the company's DNA that everyone feels responsible and so they believe that there is no need for governance. In other cases, restructuring or reorganization may have temporarily (or in some cases more permanently) disrupted the usual governance mechanisms. And finally, in companies where innovation is not perceived as particularly important there may be no one in charge.

Choosing a Model

Identifying and comparing possible models before selecting one is always beneficial. When this important step is not taken, a company runs the risk of using an inappropriate model for its condition and state of innovation maturity. Given that no model is perfect, we recommend that a company evaluates the advantages and disadvantages of each model before selecting one or changing from one to another. We also suggest that care should be taken in deciding who should be involved in the deliberations.

When choosing an innovation governance model for the company, top management needs to review and discuss several issues. Key considerations include the company's size, its place in the industry's competitive landscape, and its organizational structure. Other important considerations are the management philosophies of the top team and the board, as well as the innovation interests and capabilities of members of the top management team. For example, if the CEO or the CTO is an obvious choice for innovation leadership, this will move the choice of governance model in that direction. If there are many strong innovation leaders in the ranks of middle management, then the company might choose Model 7: a group of innovation champions.

It is also important to address the more cultural and historical parameters – for example, how the different functions work together, how important innovation is to the company's perception of itself, and the company's core capabilities (some core capabilities lead fairly easily to innovative changes; others tend to restrict the company to a limited scope when it comes to innovation).

Another question to ask is how open the company is to change, and this is a difficult question to answer. We are all open to change, or so we think. It is only after we have failed to see the opportunities or challenges that we missed that we realize that we have been wearing blinders. In our experience, some of the more sophisticated models for understanding customers, markets, and technologies can help a company to be open to a wider world. Using practices such as voice of customer (VOC) or technology mapping usually reveals that there are, as Shakespeare said, “more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”

How Many Models Do Companies Use?

Companies – especially large ones – frequently use more than one governance model. For example, the CEO may be the person in overall charge of innovation in the company (Model 2), yet that same CEO may benefit from the advice and recommendations of a high-level innovation steering group (Model 3), while mobilizing a group of middle management champions to preach the innovation gospel across business units (Model 7). In fact, in our research we found that almost every possible combination of models was used.

Using a variety of mechanisms can make it difficult to identify who, if anyone, ultimately bears overall responsibility and coordinates the tasks of all these mechanisms. This is, of course, especially true when governance practices have emerged over time and have never been properly defined. For this reason, the question of how many models to use is best answered in the context of reviewing and selecting governance models, both primary and supporting.

Do Companies Change Models?

The scope of innovation has broadened dramatically in the past decades. From the late 1980s until the early 2000s innovators, particularly in larger companies, were puzzling how to improve their capacity to develop new products. The maturation of new product development (NPD) practices in the early 2000s, along with many other factors, totally transformed the scope of innovation – it became a global phenomenon, entered into with partners and open to changes in profit/business models. Companies whose innovation governance models still focus on the architecture and implementation of “product development processes” will benefit greatly from a shift in innovation governance that addresses and includes these radical and important changes.

Companies do indeed change their models for governing innovation. Often companies alter models when there are staffing changes, especially the appointment of a new CEO or CTO. If the company adds people with experience and expertise in innovation, the model may shift to include these new hires. Conversely, if the company loses people with such expertise, a different model may need to be applied to bring the remaining talent into a more central role.

In companies where innovation governance is weak – ill-defined or affecting only some of the company's innovation concerns, for example – models may simply drift from one to another. In these companies, models are also subject to change according to the whims of senior officers – a phenomenon that is sometimes referred to as “process of the month” and which can (1) confuse people about what their goals and responsibilities are, and (2) lead people to ignore the whims of senior management (“they'll just change their minds next month – might as well keep on doing what we're doing”).

There are two motivations for change that are most likely to improve a company's innovation governance system. One is the move to a more empowered model; the other is the transition from a narrower to a broader innovation scope. In Chapters 8 and 11 we will review in more depth how Corning and Tetra Pak, respectively, empowered and broadened their model of innovation governance. At Corning, the change was triggered by the disaster of the telecom downturn, after which the company decided to create two governance models, one focusing on the radical front end of innovation and the other on projects leading to medium-term growth. Although Corning has always been a company in which innovation has played an important role, the current governance model has been greatly reinforced and made explicit, and this has had a positive effect on Corning's approach to innovation over the past few years. Similarly, Tetra Pak has considerably broadened the scope of its initial governance model – the innovation process board – by creating different high-level “councils” dealing with both process and content (i.e. strategy).

Which is Better, a Centralized Model or a Decentralized One?

Companies' response to this question varies. The major factors seem to be (1) the top team's management philosophy, and (2) the degree to which the company's business is homogeneous. Smaller companies will tend toward a centralized model, but there are also larger, diversified companies that have chosen to centralize innovation governance.

Corning is a good example of the first factor. Its top management team insists on centralized governance. Although the company has pursued many different innovations and worked with many different partners, its approach to innovation governance has remained centralized since it was founded.

We can see several reasons for this. First, innovation at Corning focuses on the use of glass. The uses have varied widely – from electric bulbs to TV monitors to photonics – and the company identifies current uses as well as what it calls “white space” potentials for this fungible substance. The location of the core of Corning's scientific resources at Sullivan Park, not far from company headquarters in the town of Corning, enables scientists working on widely different projects to cross boundaries and help one another.

Second, Corning's top management has always been centrally involved in innovation. For example, when Jamie Houghton – a scion of the Houghton family which founded Corning – returned as CEO after the telecom downturn nearly put the company out of business, his first visit was to the scientists at Sullivan Park. He did not want there to be any doubt about what he considered key to Corning's past and future success. (See Chapter 8 for more on Corning.)

The second deciding factor on whether a centralized or decentralized model is better is the degree of variability of innovation. Homogeneous companies are likely to have a centralized governance model. Like small companies, they have consistent answers to the questions of why, where, and how much. If, as the company explores innovation, these answers change, then it might be time to consider a more decentralized model in order to enable different parts of the company to pursue different paths.

An example of such a shift can be seen in Nestlé's approach to innovation governance. Although, in the main, the company's governance model is centralized, the rise of a number of so-called globally managed businesses like Nestlé Waters or Nespresso enabled it to create products and exploit markets that were very different and much more global than usual. Nestlé's globally managed businesses have therefore gained a considerable amount of freedom in their innovation governance, despite the fact that their R&D resources are managed centrally.

More heterogeneous companies are more likely to have a decentralized governance model. A clear example is United Technologies, whose business units are businesses in their own right – Sikorsky, Otis Elevator, Pratt & Whitney, and so on – and have their own governance models. Of course the models within each of these businesses may be centralized or not.

In conclusion, a clear focus on the possible models of innovation governance enables a company to raise and address questions that affect its ability to use its capacity for innovation. If these questions are not addressed, the work of innovation will fall prey to “mixed signals” from management. If they are addressed, the company will have a far better chance of succeeding in its innovation efforts – those that use existing talents and capabilities, as well as those that must be deployed to sense and respond to change. In the next chapter we will find out which models are most widely used by companies and how different companies choose, implement, and modify their models.