CHAPTER 10

Appointing Individual Innovation Champions

Example 2 – DSM's Innovation Governance Model: The Entrepreneurial CIO1

Royal DSM is a global life sciences and materials sciences company headquartered in the Netherlands. In 2009, it received the Outstanding Corporate Innovator Award from the Product Development and Management Association (PDMA). The award recognizes organizations that demonstrate exceptional skill in continuously creating and capturing value through new products and services. This award, presented to Rob van Leen, DSM's chief innovation officer (CIO), indirectly recognized the quality of the company's innovation governance. The company had indeed made a lot of progress in the way it managed innovation since transforming itself from a commodity chemical company to a high value-added specialty chemical company. Although management entrusted most of its growth and innovation mission to its business group directors, it also counted on its high-profile corporate Innovation Center, under Van Leen's leadership, to stimulate, steer, and sustain the company's innovation drive.

Going through Decades of Transformation at DSM

Few companies have transformed themselves like DSM (formerly Dutch States Mines), which started as a state-owned coal company in 1902. It successively added fertilizers, industrial chemicals, and raw materials for synthetic fibers to its product portfolio. After the country's last coal mine closed in 1975, petrochemicals became the company's focus, and profits from raw materials for plastics grew by double digits. In 1989, the company was privatized and listed on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange. Since then, and as a direct consequence of an entirely new strategy formulation process, DSM completely refigured its business portfolio and its approach to innovation.

Reconfiguring the Business Portfolio

Feeling an urgent need to improve the quality of its strategic process, which had become merely a number crunching exercise, in 1992 management launched a new collective strategy formulation approach for each business group: the Business Strategy Dialogues (BSDs). The BSD approach was complemented with the Corporate Strategy Dialogues (CSDs) in 1994. The objective of CSDs was to develop a long-term corporate strategy and set priorities for the company. The aim of the new strategic process was to ensure that DSM continued to shift its focus to more value-added products, thus enabling its entry into markets with higher growth and greater profits.

Under the leadership of the CEO, Simon de Bree, DSM continued to focus its portfolio on life sciences and performance materials. In 1998 it acquired Gist brocades (Gb), a Dutch biotechnology company that had become a leader in penicillin, enzymes, and food ingredients, all derived from microorganisms such as yeast, bacteria, and fungi. This acquisition brought DSM expertise in pharmaceutical intermediates, food specialties, and biotechnology. The culture and open approach to research and innovation at Gb were also attractive to DSM, which was larger and somewhat less flexible.

In 2000 Peter Elverding, who had succeeded Simon de Bree as CEO, led a CSD that resulted in “Vision 2005 – Focus and Value.” The vision was to move DSM away from its reliance on petrochemicals and complete its transformation into a specialty chemical company through organic growth and acquisitions. In 2000, the company acquired Catalytica Pharmaceuticals in the USA, and in 2002 it sold its large petrochemical business to the Saudi Basic Industries Corporation (SABIC). It was the largest single transaction in the company's history and provided DSM with enough cash to expand its portfolio. Roche's Vitamins & Fine Chemicals Division was acquired at the end of 2003, allowing DSM to inherit 6000 skilled employees and add more high-quality specialty products to its portfolio. This acquisition helped restore sales and achieve the target of having 80% of sales coming from specialties by 2005. It also resulted in DSM becoming the world's leader in vitamins and achieving its goal of establishing a solid life sciences activity. Neoresins was acquired in 2005 and a number of non-core commodity businesses were divested over the following years, enabling DSM to become a pure-play life sciences and materials sciences company.

In 2005 Elverding and DSM management initiated the company's “Vision 2010” which focused on completing the portfolio restructuring task that had been started a decade earlier. It also introduced a major innovation drive – creating an Innovation Center, appointing a chief innovation officer and setting an ambitious innovation growth target of €1 billion in new sales by 2010.

In 2007 Feike Sijbesma, who had come to DSM through the Gb acquisition, became CEO, and in 2010, management's new vision became “DSM in motion – Driving focused growth.” The company had completed its portfolio restructuring and was directing all its efforts on growth, in both its business groups (BGs) and new businesses, referred to as emerging business areas.

In 2011, the company reached sales of €9 billion. By that time it had more than 200 offices and sites in 49 countries and employed over 22,200 employees worldwide, with one-third of the workforce being Dutch. The combination of life sciences and materials sciences provided the company with an interesting position for growth in areas such as biotechnology and biomedical materials.

DSM is organized around five clusters and seven BGs:

- The Nutrition cluster includes two BGs: DSM Nutritional Products and DSM Food Specialties. It serves customers within the food, feed, beverages, and flavor sector.

- The Pharma cluster consists of the DSM Pharmaceutical Products BG and DSM's 50% interest in the DSM Sinochem Pharmaceuticals joint venture. Both are important suppliers to the pharmaceutical industry.

- The Performance Materials cluster and its three BGs – DSM Engineering Plastics, DSM Dyneema®, and DSM Resins & Functional Materials – supply advanced materials to a broad range of industries.

- The Polymer Intermediates cluster and its BG – DSM Fibre Intermediates – supply among other things caprolactam, the raw material for nylon.

- The Innovation Center is the most recent cluster. It was created and is headed by Van Leen. It comprises, alongside a business incubator, three new entrepreneurial businesses, or emerging business areas: DSM Bio-based Products & Services, DSM Biomedical, and DSM Advanced Surfaces.

Rethinking its Innovation Governance Approach

Until 2005 and management's Vision 2010, DSM managed innovation in a traditional way, through its R&D organization. A large research center – DSM Research – conducted research for all businesses. The director of research and development (R&D) reported to the managing board, at least one of whose members had previously been a director of R&D. The focus was on process improvements and operational excellence. Most projects were about cost reduction, and the word that was used across the organization was “standardization.” Systems were standardized and rolled out across all business groups, irrespective of their focus. Despite a number of successful innovation projects, like the one that led to the polyethylene fiber Dyneema – the strongest fiber in the world – DSM remained a rather conservative company.

Through the acquisitions of Gb and Roche Vitamins & Fine Chemicals (and later Neoresins), DSM ended up with a patchwork of R&D centers in addition to the old central R&D lab. Some sites ended up competing for projects. Between 2000 and 2005, the company came up with very few innovations, and by the end of 2005 the innovation portfolio in several business groups was empty. A new model of steering R&D and business innovation was clearly needed.

In 2005, in the context of DSM's new Vision 2010, an Innovation Center (IC) was established at corporate level to accelerate and support innovation. The notion of an Innovation Center had come from the head of corporate planning (now called Corporate Strategy & Acquisitions). The idea was to set up a unit dedicated to managing the innovation process with a strong “central push.” The concept was influenced by IBM's emerging business areas model.

Peter Elverding, the CEO at the time, chose 48-year-old Rob van Leen, then the head of DSM Food Specialties, to take on the role of creating, establishing, and running the IC. Van Leen had come with Gb when it was acquired by DSM and he had led both radical and incremental innovation projects. His good reputation and credibility within the company, together with his PhD in sciences and a business degree, made him the perfect candidate.

When Elverding had asked Van Leen to be the company's first CIO, Van Leen was busy with the Nutrition work stream of the Corporate Strategy Dialogue and he was still running his old BG job at the same time, which he was not keen to leave. But he accepted the mission after the CEO declared, “We fully trust you … It will be OK. Nobody else is better equipped to do it, so you have to do it!”

Van Leen reported to Feike Sijbesma, a member of DSM's managing board. When negotiating the level of his new position, he had insisted on reporting directly to the CEO, but was quickly reassured that Sijbesma was soon (in 2007) to succeed Elverding as CEO. Sijbesma was committed to accelerating DSM's innovation efforts and, like Van Leen, he had brought with him the entrepreneurial spirit of Gb, his former company.

There was no clear assignment when the new post was announced in 2006. So, Van Leen's first task was to draft the job description and to define the boundaries of the new IC, which was entrusted with a number of existing innovation-oriented departments. DSM's IC was defined as comprising, among other departments, a Corporate Technology Office, an Innovation Competence Center, and an Innovation Shared Service Center (including corporate licensing, venturing, and intellectual property activities). It was supposed to develop new businesses for the corporation outside the scope of the existing business groups, and for that purpose Van Leen planned to establish an incubator and an emerging business area program.

Coming from a business group himself, Van Leen established the IC as a business-oriented group, not as a staff support function.

Starting an Innovation Drive to Improve Innovation Excellence

Setting Innovation Targets

The creation of the IC, the empowerment of a high-caliber CIO, and insistent messages from the managing board all clearly signaled that top management was serious when it proposed adopting innovation as a core value. The managing board set the following six innovation targets:

- Become an intrinsically innovative company

- Adopt excellent innovation practices

- Achieve above average returns on innovation investments

- Reach €1 billion in additional innovation-related sales by 2010

- Make selective acquisitions to contribute to the €1 billion target

- Generate emerging business areas to create new business in the mid to long term.

Conducting an Innovation Diagnostic

Van Leen looked for relevant ways to measure DSM's level of innovation. With the help of an external consultant who proposed an innovation diagnostic tool, the IC performed an innovation audit involving over 700 staff using questionnaires and interviews. The consultant benchmarked DSM against 27 of its industry peers on nine indicators: innovation aspirations; innovation strategy; idea generation and validation; project management; commercialization and launch; portfolio management; external networks; organization; and culture and talent.

On most of these factors, DSM scored below the industry average when it was first evaluated in 2006. The diagnostic has since been conducted by the IC every second year, through 110 questions on the innovation process. In 2012, for the first time, the diagnostic indicated that DSM had reached the top quartile benchmark of its industry.

To follow up on the initial diagnostic, Van Leen and his staff identified the critical new projects in each BG that could contribute to reaching DSM's €1 billion sales objective by 2010. The top 50 projects were then put under the management spotlight. This Top 50 list is constantly updated and is continually monitored by Van Leen and the managing board.

Promoting Functional Excellence in Innovation

The biggest challenge for the new IC was to help the business groups contribute to the €1 billion target through market-driven, innovative sales. Initially, what was to be included in this figure or how to reach it had not been defined. To assist in meeting the target, a small unit was created to promote functional excellence in innovation. Led by an experienced business manager, it had multiple missions:

- Help the CIO assess and manage innovation

- Gather and share best practices

- Steer improvement programs

- Facilitate the BGs' innovation efforts and initiatives

- Help the BGs address and plan their innovation growth targets

- Support BG heads so they can free up people to work on innovation projects.

Establishing a Reporting System

The outcome of the diagnostic gave Van Leen's financial team a good starting point for developing reports on innovation achievements and performance. The Quarterly Innovation Reports (IRs) were launched in the second quarter of 2006 and are still in use today. These reports convey the progress of BGs and the IC in their innovation projects. They describe each BG's innovation sales, launches – new products are included for five years after launch – and the value of the project pipeline. The IC's VP of finance and control goes through the IRs in detail with each BG innovation director and the BG controller in a quarterly conference call. Their role is to identify “white space” opportunities and discuss the BG's innovation management practices. These quarterly reports are widely distributed and reviewed by the managing board, something that was not originally welcomed by the BGs that were performing at the bottom of the list.

Soon after, a Top 50 Boost Report was launched. This complementary report, produced twice a year, allowed Van Leen and the managing board to focus on and evaluate the top 50 projects contributing to the €1 billion target for 2010. This report has now been extended to include the top ventures from the emerging business areas. It is reviewed annually with the managing board.

An existing intranet project management tool, called Project Plaza, was rolled out throughout the company to support innovation projects and portfolio management. Through this portal, business managers and, for example, their controllers can conduct feasibility studies, analyze business cases, select the right projects, check sales, and quantify the value of projects.

Creating an Idea Box

Over time, more tools and processes were put in place. After a two-year pilot in Switzerland, corporate idea boxes (IBs) were launched in the second half of 2008 to encourage all employees to contribute to an integrated innovation culture. BGs that wished to implement an IB had to set up an infrastructure to manage it, with an IB manager, an IB owner, and idea screeners. The IB itself was not unique to DSM. What was unique was its challenging nature, prompting clear answers to why an idea was needed and what value it would bring to the company.

Not all BGs adopted the system immediately, something that the DSM culture allowed, but its use spread gradually and proved highly beneficial.

Distributing Innovation Awards

DSM's innovation awards program recognized and rewarded scientists who had proved excellence in pioneering research that led to innovative products and applications. A Nutrition Award recognized innovative research in human and animal nutrition. A Science & Technology Award encouraged young scientists to conduct creative, groundbreaking research. The Performance Materials Award recognized excellence in innovative research in the field of performance materials. The internal awards program was expanded to recognize both individuals and teams for excellence in science and intellectual property, but most importantly integral innovation. The awards program was generally well accepted and valued.

Restructuring the Management of Technology and R&D

As a scientist himself, Van Leen had personal experience of R&D management. His former responsibility as a BG head had also convinced him of the need to introduce a clear focus on market-oriented radical innovation and a much higher degree of business orientation. So he promoted the concept that innovation and the underlying R&D, manufacturing, and business development processes had to be managed by an entrepreneur from start to finish.

Implementing a New R&D Model

Van Leen believed in having an entrepreneurial business manager oversee the market research and the design phase of projects. Input into the pipeline would come from the Business Strategy Dialogues, and the innovation project would be driven by the needs of the business group. A project manager from R&D would head up the technical part of the project, reporting to the entrepreneur. The entrepreneur has two key roles: (1) to drive and oversee the product/business specification phase, and (2) to be the interface manager with all functions involved in the project or program.

According to Van Leen's new model, the concept of a central research lab was abandoned and a hybrid model was adopted, similar to the way research had been managed at Gb, where product and application development were under the business units and funded by them. Competence-oriented groups were created to serve the whole company, but they were located in specific business groups. Thus there was a Biotechnology Center at the former Gb site; a Nutrition Center at the former Roche Vitamins site; and an Organic Chemistry Center and a Materials Science Center at the largest DSM site.

R&D activities were organized along three axes, with separate responsibilities for managing people (leading a unit or department), focusing on science (building expertise in a particular discipline), and project management (managing a project team). This functional set-up was designed to clarify the different responsibilities, accountabilities, and authorities. And the three-axis model was intended to simplify career development routes within R&D, as young scientists and engineers could select one of the three axes and follow a career path corresponding to their choice.

By 2012, after a number of acquisitions of small specialty companies in different parts of the world, DSM had 35 R&D sites. The main R&D centers, however, were still located in the Netherlands, Switzerland, China, and the USA. The total R&D spending was 5% of net sales. R&D centers collaborated closely on fundamental research with the venturing group as well as with outside parties in academia and industry. The technology base was kept state of the art by a Corporate Research Program, directed by the CTO, which consumed about 10% of the total research budget.

Setting up a Corporate Technology Responsibility

The most radical change was to bring the CTO and his office into the IC, reporting to Van Leen. But the CTO remained, together with his boss, part of DSM's leadership council, i.e. the top 30 senior executives in the company.

The CTO has a corporate budget to ensure that new initiatives are included in the R&D pipeline. His role is to drive the corporate R&D competence plan and fill any gaps. However, he has no direct responsibility over DSM labs, which fall under the authority of each BG's R&D director.

The CTO focuses on three major tasks (besides making the new organization work): (1) chairing the DSM Science and Technology Council (DSTC), which consisted of the chairmen of the R&D councils of the clusters, among other people; (2) allocating, funding, and supervising the corporate research budget and programs; and (3) steering and executing the recommendations of the Scientific Advisory Board that worked for the DSTC.

Mobilizing Innovators in Business Groups

Originally, the attitude of BG heads toward the Innovation Center and its role varied considerably. Van Leen had full support for his initiatives from some business groups, typically those with a newly arrived BG head. Other BGs were initially reluctant to see the IC becoming too involved in their process, either because they wished to remain independent or because they did not see what added value the IC could bring to their business.

Van Leen was aware that he was treading a fine line. How much should the IC be involved in improving the innovation process in a BG? He wanted them to be better at innovation but he did not want to interfere or take over responsibility.

Gathering Innovation Enthusiasts to Spearhead Change

To promote innovation, each BG had to embark on an improvement program. Because there was a clear difference in the enthusiasm, pace, and determination of the various BGs, Van Leen set up a network of so-called innovation enthusiasts under the name the “Billion Bunch.” The name derived from the fact that they were supposed to help DSM achieve the €1 billion target in innovation sales by 2010. Their objective was also to exchange best practices across units on managing innovation. However, since BG heads appointed members of the “bunch,” their profile and motivation were not always ideal.

This is one reason that the Billion Bunch network was disbanded after a couple of years and replaced by a network of innovation directors. Van Leen wanted indeed to have a real and empowered counterpart in each of the BGs. Today, these innovation directors lead teams of business development managers, and some also have the BG R&D head reporting to them (similar to the CIO–CTO relationship). They remain part of their BG but functionally report to Van Leen in their innovation mission.

These innovation directors and the heads of the IC incubator and the functional excellence unit are now part of an Innovation Council chaired by Van Leen. The role of this council is to work together to achieve the company's new innovation target. Indeed, the original objective was vastly exceeded – sales from innovation reached €1.3 billion in 2010. The new corporate innovation target is now to achieve 20% of total sales in 2015 from products and solutions introduced within the previous five years – and the definition of new products has been clearly specified, which is critical for this type of measurement. This is a considerable objective for a chemical company.

Collectively, members of the innovation council discuss the composition of the radical innovation project portfolio and make recommendations to the managing board, which makes the final decisions. Individually, each innovation director is assigned an innovation target corresponding to the situation of his/her BG – some higher, others lower – in order to ensure that the average of all BGs reaches the 20% target. This means that the innovation directors personally follow the progress of their projects from the Top 50 list and serve as the BG representatives of the IC's functional excellence activities. In addition, each innovation director is in charge of a topic or an innovation theme, which he/she leads DSM-wide.

As part of its regular meetings, the innovation council also looks at individual BG project portfolios. They might, for example, advise that the BG increase the level of spending on a particular project by a factor of five in order to develop a cluster of new applications. This, however, means reallocating budgets at the DSM level, which is not an easy task.

Creating a Product Launch Team

Traditionally, DSM did not proactively launch products in its markets. The company lacked marketing and sales talent and experience. So, as part of the innovation boost efforts, and in collaboration with the chief marketing officer, Van Leen hired marketing specialists from inside and outside the company and set up a commercialization and realization team to support the BGs' efforts to take innovations to market. Originally, this service was offered to the BGs free of charge, but they now pay for it.

Launching a Culture Change Program

Together with Van Leen, a number of senior managers felt the need for DSM to become more entrepreneurial, but how? It started with supporting risk taking, something the managing board was willing to do. They also saw the need to change in at least two main areas: (1) to move from a product- and technology-driven culture to one focusing equally on business models and product co-creation with customers, and (2) to foster an attitude of curiosity and customer empathy and interest, a must in life sciences.

Van Leen was fully aware of the need for change, which is why he had asked HR to design an ambitious Innovation Learning Program with the support of some of the BG and functional excellence staff. Together, they planned a number of different management development programs targeting various hierarchical levels and functions. In 2012, the first round of programs had involved the leaders and owners of the top 50 projects.

Building a New Business Creation Infrastructure

Van Leen inherited a number of existing and important corporate functions like the Intellectual Property department and the Licensing group. These two units were to provide the bulk of the IC permanent staff, but Van Leen saw limited ways for him to add extra value to them, preferring to focus instead on innovation- and business-building activities.

Mapping Strategic Choices

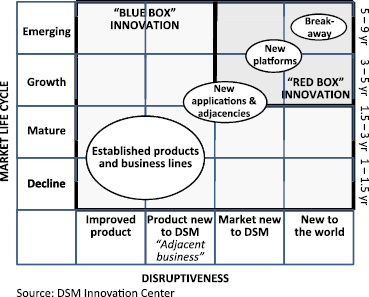

As part of its recent Corporate Strategy Dialogue input, Van Leen adopted a tool to map the company's innovation initiatives (refer to Figure 10.1). The “blue box” quadrants (in light gray on the figure) represented opportunities for incremental product creation, whereas the “red box” (in dark gray) featured more radical areas for business creation. The red box was defined as containing future new platforms consisting of projects, ventures, and acquisition possibilities. The “blue box vs. red box” concept was quickly adopted by the organization, all the way up to CEO level, and was used to characterize the company's innovation strategy. Blue box projects generally belonged to the BGs, whereas red box ones – with a few exceptions that were allocated to BGs – entered the realm of the IC, notably the incubator and the emerging business areas.

Figure 10.1: DSM Innovation Matrix

The composition of the red box portfolio was discussed and agreed upon in the innovation council. Originally, 45 projects were allocated to the red box quadrant. After multiple discussions within the innovation council, the number was reduced to fewer than 15 and the projects were allocated mostly to the incubator and the emerging business areas. A critical factor for the selection of these projects was their potential contribution to building new technology and business platforms, and the potential market size of these platforms. The benchmark retained for these new business platforms set the ideal level at €250 million in sales to be achieved within a 10- to 15-year time span, and with higher margins than DSM's current businesses. Individual stand-alone projects were retained as long as they were part of existing platforms or businesses. Overall, a significant R&D budget envelope (25% of the corporate total) was allocated to the development of red box projects.

Beefing Up Corporate Venturing

Venturing was made part of the IC, and it soon came to play an integral part in the open innovation process. The group teamed up with innovative players all over the world and invested in promising start-ups. The objective was to give DSM access to new technologies and innovative products aligned with the company's growth strategy. Participation in start-ups ranged from 5 to 20% of their capital, giving these companies financial support as well as access to DSM's expertise, resources, and networks.

The diversity of the venturing portfolio gave DSM a broad window on the world in a wide range of markets including emerging economies.

Creating a Business Incubator

The business incubator (BI) was created – out of the former Corporate New Business Development unit – to be the originator of and platform for large new business opportunities. The BI was to capture larger dynamic shifts in the market and breed more radical, slightly longer-term innovations leading to new business models and higher value products. Its focus was on potential technology and market platforms, not on individual, stand-alone projects.

By 2008, the BI had focused its activities on four innovation areas: climate change and energy; health and wellness; functionality and performance, and emerging economies. A fifth area, the X-factor, was temporarily created in 2008 to leverage the combined knowledge and technology in life sciences and materials sciences. The most promising projects from the BI were expected either to be turned into an emerging business area or to be transferred directly to a business group or even sold off.

The incubator had a small team and a lean infrastructure, which Van Leen was considering how to build further. A first step in that direction was the setting up of local incubators in the emerging markets of India and China.

Seeding Emerging Business Areas

Emerging business areas (EBAs) were created with the mission to look at significant new trends in industries and markets, identify potential innovation pockets and relate these to DSM's current market strongholds and technology position. EBAs were defined as broad platforms within which a series of new projects could be launched with the objective of creating entirely new businesses.

DSM's top management wanted entrepreneurial teams, rather than traditional DSM functional teams, to lead these EBAs. Originally, the managing board and Van Leen screened all existing opportunities, reducing the number of possible projects from 14 to four by deciding to allocate some to the BGs and kill others or put them on the back-burner. The four areas of opportunity that were selected were: white biotechnology (biofuels), biomedical materials, personalized nutrition, and specialty packaging.

In fact, the last two EBAs were canceled after four or five years of trying hard. Personalized nutrition – management felt – was a valid concept but came too early for the market. Specialty packaging did not bring spectacularly big solutions to the fore and was terminated in 2010, although an interesting packaging solution for cheese was transferred to DSM Food Specialties, where it is flourishing as part of the dairy portfolio. This allowed management to send a clear signal to the organization – stopping projects is OK.

Meanwhile, a project from the incubator that had developed an effective anti-glare coating for glass surfaces was turned into an EBA under the name advanced surfaces. Management had been tempted to kill the project for lack of market opportunities – the first application was limited to the glass picture frame market. But the project was re-evaluated and a huge new application identified in coating solar cell panels to increase their productivity. The additional energy produced justified the cost of the coating.

This experience with the early EBAs clearly showed the need for a venture management process. So the IC developed a real stage-gate process for new ventures to provide management with an overall approach to new business creation.

In 2012, the Innovation Center housed three EBAs:

- Bio-based Products & Services – the former white biotechnology platform – which exploits opportunities in advanced biofuels. The unit was transferred to the USA, the largest market for this type of product.

- Biomedical, which conceives, among other applications, biodegradable structures contributing to the development of bones and cartilage in patients. It was also based in the USA.

- Advanced Surfaces, which proposes coating solar panels for greater electricity generation and follows other applications in trapping light. It seems to have considerable potential.

By the end of 2012, all three EBAs were net cash eaters and management was ready to invest huge amounts in their development. Van Leen estimated that all three could become extremely profitable. But they all need to complete 10 to 15 years of maturation before they start delivering.

Growing EBAs and Extending the EBA Portfolio

Given the amount of R&D money invested in the development of EBAs, their progress was a regular item on the managing board's agenda. Van Leen personally devoted 70 to 80% of his time to the three EBAs and the business incubator. This included the time spent in coaching their organic growth strategy as well as in identifying and evaluating partnership and acquisition candidates. Several focused acquisitions had been concluded to boost their expertise and market coverage.

Van Leen was aware that he might be expected to grow new EBAs, since the ones under his leadership were reaching their growth stage. This could create a gap to develop a new EBA. The difficulty was identifying suitable technology and market platforms for these new businesses.

Showing the Way at the Top

If Van Leen, as CIO, has been entrusted with overall responsibility for innovation at DSM, he can count fully on the support of the CEO, Feike Sijbesma, who is seen as the ultimate champion of innovation in the company. Sijbesma believes that, for a science- and technology-based company like DSM, innovation is key to corporate growth and profits. He stresses it constantly, in public – he attends all internal and external innovation events – and in private management review sessions. But he also takes concrete and highly symbolic steps to underline management's commitment.

Sijbesma explained: “In the 2008/2009 economic crisis, we initiated a cost-saving program everywhere, but not in technology and innovation! Some of my managers thought that it was unfair that we would not cut costs in R&D. I said to my R&D managers: If you can cut costs in R&D by becoming more efficient, that's fine, but I don't want you to cut costs by doing less. This passed a strong message to the organization!”

Besides regularly reviewing the various innovation reports sent to the managing board, Sijbesma pays particular attention to the top 50 projects, to their staffing and to the resources allocated to them. Given his own technical background and knowledge, he is naturally interested in supervising the whole R&D process but he recognizes that his involvement has advantages and disadvantages for Van Leen and the technical organization. He also maintains a strong relationship with Van Leen and a particular interest in the new business platforms that Van Leen has started in the EBAs.

One of the other important ways in which Sijbesma feels that he can contribute to innovation is by promoting the company's values. The four values he emphasizes have a direct bearing on innovation:

- External orientation: Sijbesma encourages the “proudly found elsewhere” approach, in contrast to the resistance to ideas “not invented here” that was prevalent in some parts of the organization. He repeats it often: “I don't mind if you didn't invent it!” In this spirit, he has decentralized BG headquarters. Only three BGs have their headquarters in Holland. The others are based in the USA, Singapore, China, and Switzerland.

- Accountability for performance and learning: Sijbesma stresses the importance of learning from failed projects. He recognizes that deciding to kill a project is always difficult, but he encourages evaluations to be carried out when there are “project funerals,” because these evaluations promote individual and collective learning.

- Collaboration: Sijbesma is a strong advocate of the “One DSM” concept and he extols the virtue of looking internally for help within other BGs to solve internal problems, something that was not naturally done before.

- Inclusion and diversity: Sijbesma wants to attract a broader mix of people and to encourage different mindsets and behaviors. The managing board includes only two Dutchmen out of five, and two members are based overseas. He promotes this attitude by organizing specific cultural sensitivity training programs, for example on how men and women think differently.

DSM's Outlook and Challenges: A Continued Focus on Innovation

DSM's Vision 2005 was essentially about business portfolio reconfiguration. The subsequent Vision 2010 focused on creating an innovation governance infrastructure with the appointment of Van Leen as CIO and the creation of the Innovation Center. It also set a first growth target for innovation, i.e. €1 billion of new sales by 2010, an objective that was exceeded. The latest vision, “DSM in motion – Driving focused growth,” has established not one, but three deadlines:

- 2013 for a focus on profitability targets: Management wants to create a sense of urgency about profitability.

- 2015 for new sales and growth targets: Management wants innovative products and solutions – developed within the previous five years – to account for 20% of total sales by 2015.

- 2020 for sales aspirations for the three EBAs: These EBAs are designed to contribute an extra €1 billion in profitable sales, while new EBAs might be developed.

These objectives are based on four growth drivers: (1) high growth economies; (2) innovation; (3) sustainability; and (4) acquisitions and partnerships.

Van Leen is aware of the importance of the double mission that has been entrusted to him and the IC in order to achieve the company's objective. On the one hand, he needs to grow new high-margin business groups through technological and business model innovation; on the other hand, he has to continue to help the BGs improve their processes, which requires him to be both diplomatic and challenging.

Sijbesma agrees and credits the company's innovation governance model – its CIO and IC – for its achievements so far: “The IC has two roles. First, it is where new growth bubbles are developed; and second, it is needed to supervise where we spend our money! Our model works well and our organization has learned to use this model. If it works, let's not try to do something different. In technology and innovation, we need a long-term approach and we need to make sure that people learn to work in that system.”

Note

1 This chapter is derived, in part, from the business case “DSM: Mobilizing the Organization to Grow through Innovation” by Daria Tolstoi and Jean-Philippe Deschamps (2009) Ref. IMD-3-2111, distributed by www.thecasecentre.org.