Chapter 9

Go, Team! Driving Engagement through Team Development

In This Chapter

![]() Knowing what makes a team great

Knowing what makes a team great

![]() Understanding how groups develop

Understanding how groups develop

![]() Leading teams from afar

Leading teams from afar

![]() Using activities to build team cohesiveness

Using activities to build team cohesiveness

![]() Conducting a high-impact team workshop

Conducting a high-impact team workshop

One of my all-time favorite jobs was working as a grocery clerk at a neighborhood grocer throughout high school and college. Over the years, when I've bumped into former co-workers, we've often reflected on what an amazing experience we had working there. I've come to realize that stocking shelves is not in and of itself terribly engaging. But working with great co-workers, helping each other out, and having great camaraderie, trust, and love for one another is engaging. In other words, a great team environment can engage a person as much as a great job can! For the details on how team dynamics can act as a significant engagement driver (or a big-time driver of disengagement), read on!

Yay, Team: Identifying Characteristics of an Engaged Team

Early in my career, when facilitating supervisory training, I used to tell the participants the characteristics of an engaged team. Eventually, however, I figured out this was something most people already know. After all, everyone's been on a sports team, a dance team, in Boy Scouts or Girl Scouts, on church committees, or in a play group, and has seen what works and what doesn't. In fact, I'm so confident you're already familiar with the characteristics of an engaged team that I'm tempted to just move on to the next section. But in the interest of being thorough, I'll spell it out here. Engaged teams demonstrate the following:

- Accountability

- Authority

- Clarity of roles

- Decisiveness

- Direction

- Mutual commitment

- Open communication

- Performance

- Productivity

- Respect

- Selflessness

- Transparency

- Trust

- Vision

But that's not all. For a team to be truly engaged, focused, and motivated, it must also demonstrate the following:

- Accessibility

- Agility

- Appreciation

- Balance

- Celebration

- Collaboration

- Complementary skills

- Diversity

- Drive

- Empowerment

- External focus

- Flexibility

- Fun

- Morale

- Ownership

- Pride

- Recognition

- Sense of purpose

- Visibility

Unfortunately, many teams don't demonstrate these characteristics. In other words, these words describe what characteristics teams should have, not what they do have. Why? For one, people get busy, and they don't always feel they have the time to exhibit these ideal behaviors. Additionally, some people are just mistrusting, cynical, or skeptical by their very nature. They're not bad people — these traits are just part of their DNA.

For many, the default is to assume the worst of people, or that people have bad intentions. But perhaps the most significant hallmark of a successful team is that members assume good intentions. In addition, people on successful teams hold each other accountable when they see their teammates demonstrating less-than-ideal characteristics.

Stormin’ Norman: Exploring Tuckman's Stages

In 1965, psychologist Dr. Bruce Tuckman proposed a model of group development that he called “Tuckman's Stages.” This model included four stages:

- Stage 1: Forming

- Stage 2: Storming

- Stage 3: Norming

- Stage 4: Performing

To help you understand this model, let me give an example: Suppose you and your partner decide to have a child. Fast-forward nine months, and — boom! — you bring the baby home. You're crazy excited. You'reforming a family!

Soon, the reality of parenting sets in. The baby won't sleep through the night. He cries all the time. You and your partner are exhausted and increasingly irritated with each other. You haven't had an evening out together, just the two of you, in months. Welcome to the storming stage of your new family, or team.

Eventually, the baby starts to sleep. He figures out how to soothe himself, so there's not so much crying. You've found a few babysitters to step in so you and your partner can have some time alone. You settle into a routine. This is your team's norming stage.

Before you know it, your baby is 2 years old. Although some challenges remain (they don't call them the “terrible twos” for nothing), things have settled down. Your “team” is performing quite well! In fact, having forgotten how painful the storming stage was, you're even thinking of having another child. When you do, you'll be right back at the forming stage, and the cycle will start again.

Of course, growing families aren't the only “teams” that follow Tuckman's Stages. These stages also apply to work teams and to the lifecycle of companies. And although this example showcased what happens to a “team” when new people are added, the same cycle occurs any time a significant event occurs, such as an acquisition, starting a new project, converting to a new system, organizational changes, changes to company leadership, or the departure of team members. (Just ask any parent whose child goes off to college about how their “team” has changed!) These days, the one thing we can count on is that change is a constant. Understanding Tuckman's Stages can help leaders ensure that team members stay engaged amidst change.

This simple but powerful team-development model has stood the test of time, and continues to be used even today by academics and consultants in classrooms and workshops across the world. The key points to keep in mind about Tuckman's Stages is that they're a natural aspect of team development, they should be anticipated, and in many ways they're part of a virtuous cycle.

The forming stage

Teams, whether at work or at home, always begin in this stage, and will return to this stage whenever a significant change occurs — for example, when people are added to the team, when members of the team leave, or when a new project starts.

In the forming stage, particularly on new teams, team members tend to exhibit the following behaviors:

- They're fired up to be part of the team, and they're eager for work ahead.

- They have some anxiety and uncertainty. They're wondering things like, “What's expected of me?”, “How will I fit in?”, or “How will my performance measure up to others?”

- They may be reticent to ask questions and share ideas. During this stage, politeness often prevails. On the surface, team members will appear cooperative, and there will be lots of face-to-face agreement. Often, however, there are unspoken opinions and silent disagreements.

- They may test the situation and each other.

- Their commitment and motivation levels are high. Productivity levels, however, are merely moderate, as people are still learning the goals, the roles, and what's expected.

- Defining and clarifying team and individual goals, roles, expectations, and practices.

- Discussing past practices to determine what worked and what didn't.

- Building relationships and rapport by ensuring that the team spends time together and engaging in team-building activities. (You'll learn more about team-building activities that foster rapport and engagement later in this chapter.)

- Establishing team norms (that is, the “rules of the tavern” and best practices for communicating, making decisions, and so on).

- Assessing strengths and weaknesses of team members and identifying ways they can help each other improve.

- Articulating your management philosophy, your strengths, and your weaknesses, and asking the team to provide ongoing feedback.

For maximum engagement, team leaders must help team members understand and manage transition and change. That includes familiarizing team members with the four stages of team development (forming, storming, norming, and performing). This will help team members prepare for what's coming and deal with the inevitable highs and lows. Team leaders must also teach and model the skills and behaviors they want to see on their teams, and recognize those skills and behaviors when they see them.

The storming stage

Over time, teams will move from the forming stage to the storming stage. Why? Because as team members become more familiar with each other, they become comfortable enough to state their true feelings and beliefs, which inevitably leads to disagreements.

During this stage, conflict is the watchword. Think: Hell's Kitchen with Gordon Ramsay. Team members may experience some of the following:

- They may discover that the team doesn't live up to early expectations.

- They may feel frustrated, confused, or angry about the team's progress or process (or lack thereof).

- They may react negatively to the team leader and to other members of the team. Power struggles may ensue.

- They may have conflicts and disagreements about goals, roles, and responsibilities, expressed openly or behind the scenes.

- Commitment, morale, and productivity may take a downturn.

- Bringing conflict out into the open

- Acknowledging with the team that storming is natural, inevitable, and essential to the growth of the team

- Creating forums and encouraging open discussion of issues, even if it's directed at you as the leader

- Establishing norms for constructive discussion and debate

- Reinforcing positive conflict-resolution efforts

- Balancing individual needs with team needs

For more on resolving conflict, see Chapter 5.

In addition, team leaders should revisit and clarify goals, roles, and expectations. (Note that teams may move more quickly through storming if the tasks in the forming stage were done well.)

The norming stage

In the norming stage, things begin to smooth out. Turbulence subsides, a sense of calm prevails, and commitment and productivity take a turn for the better.

For team members, this stage is characterized by the following:

- They begin to resolve the discrepancies between their expectations and the reality of the team experience.

- They have an increased understanding of accountabilities and expectations.

- They develop self-esteem, as well as trust and confidence in the team.

- They become more comfortable expressing their “real” ideas and feelings.

- They start using “team language” — that is, saying “we” rather than “I.”

- Being less directive and more participatory

- Collectively reviewing team norms, processes, and practices and adjusting them based on what's working and what isn't working

- Encouraging and giving recognition for taking initiative, taking risks, creative problem solving, and seeking and acting on feedback

In addition, the team leader should continue to build trust and relationships through personal interactions and team building.

The performing stage

Ah, the performing stage . . . the sweet spot of group development. In this stage, life is good. Members feel excited to be part of the engaged, high-performing team, which functions as smoothly as Barry White at a singles bar. That's not to say there's no conflict or disruption, just that the team has set rules for handling it.

During this stage, team members

- Are focused on team versus individual results

- Understand and take advantage of team members’ strengths, valuing their differences

- Exhibit high levels of confidence

- Demonstrate a sense of true collaboration and shared team leadership

- Demonstrate high levels of commitment, morale, and productivity

- Can function at a high level, even absent of the team leader

Not surprisingly, people on teams in this stage are hesitant to introduce change, thereby reverting to the forming stage. After all, if it ain't broke, don't fix it, right? Besides, moving through all those stages can be painful! But introducing change is a must. Otherwise, the team risks becoming complacent, stale, or overconfident.

- Giving people more responsibility and delegating some of your tasks to develop team members’ technical, business, and leadership skills

- Providing more feedback and additional “big picture” information to help team members make links to the larger organization

- Injecting new perspectives into the team via transfers in or out, promotions, new hires, external expertise, market intelligence, and benchmarking

- Continuing to celebrate individual and team successes

Putting it all together

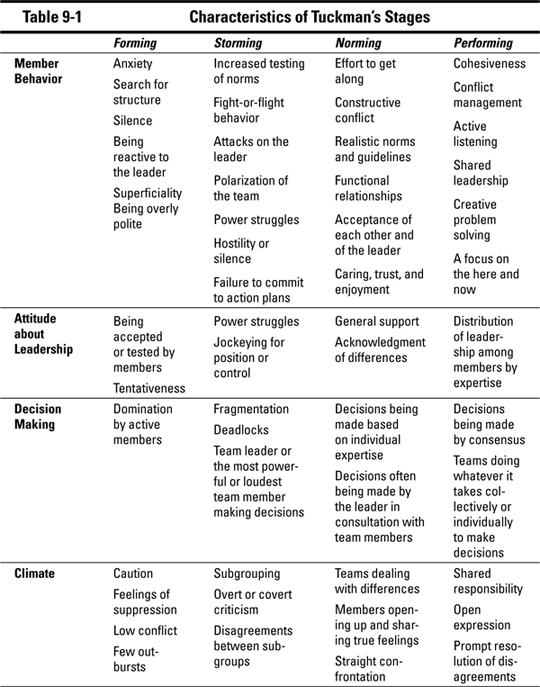

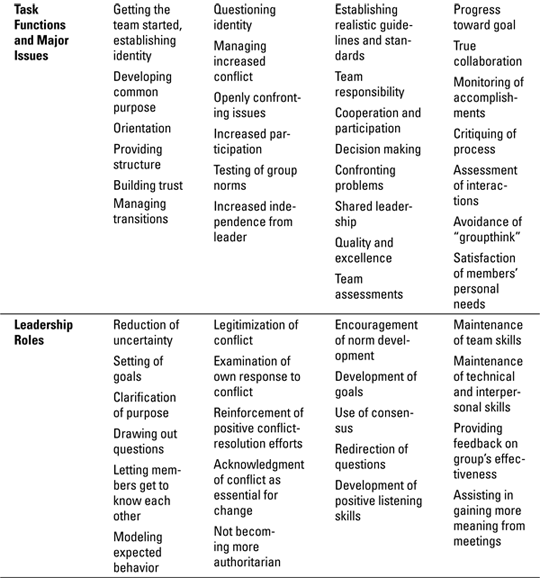

Need a little assistance assimilating all that information about Tuckman's Stages? Table 9-1 should help.

From a Distance: Leading Teams from Afar

If you're charged with leading a team from afar, you'll need some special competencies. Most notably, you'll need the ability to manage boundaries and barriers. Staff in remote locations face significant obstacles — logistical and otherwise — which impede and even prevent success. You have to be prepared to help your team navigate those obstacles. In addition, you'll need to master technology for communication and collaboration, such as Microsoft SharePoint, Skype, extranets, and of course, e-mail. (Note that this includes understanding e-mail etiquette.) Finally, particularly if your staff are located in other regions or countries, you'll need a strong dose of cultural awareness.

- Focus on relationships first, and cultural and language differences second. Get to know your employees. Do you know their family situation? Do you know the names of each employee's spouse and kids? Do your remote employees feel you care about them as people? Remember: You can't be an empathetic boss without knowing your employees personally.

- Develop a way to share information. When managing remote or virtual employees, technology is the great equalizer. Make sure remote employees have an opportunity to share their information with the team via SharePoint, Skype, webinars, and so on. The idea is that they should feel like they're in the room with you.

- Consider time zones and share the associated sacrifices equally. If you're leading people in a different region or country, be sensitive to their time zone. Shift calls so they aren't always the one whose phone rings at 11 p.m. Rotating time-zone hardships is a simple way to reinforce that you're sensitive to the work–life balance.

- Identify communication preferences for team and individuals. Some individuals and/or teams may be more visual by nature, so using tools to share documents may be better than describing them over a conference call.

- Create a team-level communication protocol and stick to it. This protocol might outline how communication will be handled, when team members can expect communications, and what to expect on an ongoing basis.

- Be accessible. Although you do need to set some boundaries if there are time-zone differences, you have to make yourself more available than you might if you were right down the hall. Remote employees are prone to feeling isolated. If, when they reach out, they get the “I'm too busy right now” treatment, their sense of isolation will increase exponentially.

- Develop ways for your remote employees to virtually “stop by.” Have a virtual open-door policy and encourage your remote employees to “swing by” when they need to chat, have a question, want to check in, and so on. Confirming that it's okay to text or instant-message you whenever and wherever will minimize their loneliness. Texting is often a great “check-in” communication tool because it's quick and informal and happens in real-time.

- Make sure remote employees have the opportunity to participate in company initiatives. These include surveys, task teams, meetings, socials, holiday parties, and so on. Be aware of the “out of sight, out of mind” phenomenon that exists with remote employees. Camaraderie is a significant engagement driver — and even more so with remote employees, who don't get the benefit of the “water cooler” companionship that in-house workers experience. Effective remote managers go out of their way to include their remote employees on intradepartmental initiatives and special projects.

- Communicate more often, and in different modes. Send frequent informational e-mails, and regularly keep in touch with remote team members with phone calls or other forms of communication.

Team Player: Exploring Team-Building Activities

One of the most important things a successful leader does to foster engagement, particularly in the early stages of a team's development, is to build trust and relationships. In this case, trust is the confidence among team members that their peers’ intentions are good and, consequently, that it's unnecessary to be defensive or wary within the group.

Building trust doesn't just happen. It requires shared experiences over time, evidence of credibility and follow through, and an in-depth understanding of the unique attributes of each team member. Ultimately, the team leader and team members must become comfortable with each other, and get to know each other beyond a purely work-related context.

Fortunately, team leaders can accelerate this process, building trust in a relatively short period of time, by taking a few specific actions, or team-building activities. These activities enable leaders to build relationships and trust through personal and professional self-disclosure, and to increase self-awareness and awareness of each other's strengths, blind spots, and unique contributions to the team.

Before getting into the specific activities team leaders can do to build trust, this section discusses the ins and outs of running a successful team-building activity and common challenges you'll face.

Running a successful team-building activity

In an ideal world, you'll have the budget to hire team-building consultants, or perhaps have qualified organizational development (OD), training, or HR folks to lend you a hand. If not, this section has tools to help you lead the team-building activity yourself.

Before the team activity, you'll want to be sure you truly understand the ins and outs of the activity. You want to be crystal clear about what will happen, when, why, and how. Also, make sure you have all the necessary materials, and test them to make sure they work with the activity. Next, set up the room as needed, making sure all tables, chairs, flip charts, and whatnot are in place. Finally, anticipate any potential problems, and take steps to prevent them.

At the beginning of the activity, welcome your team. Give them a brief overview of the activity — why you're doing it, the steps or rules, and so on. Show some enthusiasm! You want to fire up the group, so they become interested and excited. Before moving on, make sure the team understands the activity. Set clear expectations, and give team members the opportunity to ask questions.

When everyone's up to speed, distribute the necessary materials and get started. As team members work, be encouraging and supportive. Be sure to thank whoever goes first — that takes courage! Watch for opportunities to clarify instructions. If the activity is timed, keep team members abreast of how much time remains.

When the activity is over, conduct a debriefing session. Ask questions — either the ones provided with the activity or your own. Here are a few examples of questions you may ask during the debrief:

- Why is it important for us to get to know each other outside a purely work-related context?

- How difficult (or easy) was it for you to share information about yourself with others?

- How can we learn more about each other back on the job?

Tackling common challenges

Sometimes, conducting a team-building activity is a little like herding cats. In other words, it can be challenging. Here are a few challenges you may face in your team-building efforts and some steps you can take to overcome them:

- People don't want to participate. Unfortunately, not everyone is thrilled by the prospect of a team-building activity, particularly if they're shy. To get them onboard, clearly articulate the purpose of the activity. Remind them that in order for it to be team building, everyone must participate. Reassure them that everyone will participate, and that no one will be singled out or otherwise embarrassed. If the activity allows, have your more outgoing team members go first (or go first yourself ).

- People are unclear about directions. Fortunately, this one's easy to address. Just be sure to speak slowly when explaining the activity. Pause after each direction to let it sink in. When you're finished, start over and repeat the directions. Ensure that any difficult or confusing steps are put in context.

- There aren't enough materials. This challenge also has an easy fix: Make sure you bring more than enough materials for all participants.

- People don't contribute during the debrief. As I mention earlier, after asking a question, pause and silently count to ten. This gives people time to think. Reword questions only if someone says he didn't understand. If no one answers, offer your own observation, and then ask what others saw or felt that was similar or different from what you shared. As a last resort, call on someone by name to respond. Start with a more outgoing team member, who won't feel embarrassed by the attention.

Looking at effective team-building activities

This section contains several team-building activities that you can use to strengthen your own team.

Hello, My N.A.M.E. Is . . .

In this exercise, members introduce themselves by presenting their first names as acronyms. This allows them to learn interesting things about each other.

Materials

None

Instructions

- Give the group five minutes to think of interesting facts about themselves that correspond to the letters of their first names.

- Share your acronym as an example.

- Have each person share his or her acronym.

Example

“Hi. I'm Logan. L is for Led Zeppelin, one of my favorite rock groups. O is for Ohio, which is where I live. G is for German, the only foreign language I know. A is for Aunt Wendy, my favorite relative. And N is for No Fish because I don't eat seafood.”

What Makes Us Tick?

Provide members with a way to share things about themselves that aren't observable to others, but have an impact on others. This gives team members an opportunity to look for ways to support each other.

Materials

- Flip chart paper/whiteboard (or “web meeting” equivalent)

- Blank sheets of note paper

Instructions

-

List sentence starters on a flip chart or whiteboard.

Include a few or all from this list, as time allows:

- What is important to me in the next six months is . . .

- I feel very confident that . . .

- I'm not as confident that . . .

- The team can help me by . . .

- If you see me doing something that you think is a mistake, please . . .

- The best way to communicate with me is . . .

- Allow five to ten minutes for team members to write down their answers.

-

Go around the group one question at a time, allowing each person to share his or her response to the question.

Allow time for clarification and some reaction and discussion to make it interactive and animated.

Debrief

During the debrief, ask the following questions:

- What did you hear in common with particular team members?

- Reflect on the differences expressed during this exercise. How can those differences become an asset for the team?

- What suggestions do you have for how we can honor each member's needs?

Option

Give team members a worksheet with the sentence starters listed as pre-work so they have more time to think through their answers.

A Penny for Your Thoughts

This lighthearted activity reveals a quick, personal fact about each person.

Materials

One penny for each participant. (Ideally, these should be shiny, easy to read, and less than 20 years old.)

Instructions

-

Give a penny to each person.

As you do this, try jokingly asking whether they realized they were going to get a cash bonus today.

- Ask each team member to share something significant or interesting about himself or herself from the year on the penny.

- Go first to set the example.

- As people share, let the other members ask questions.

Examples

“My penny is from 1999. That was the year that I let my husband talk me into going skydiving with him.”

Variations

Have team members explain what they would do differently if they could relive that year. Alternatively, have them say what their favorite song, book, movie, or TV show was from that year. Allow participants to use their smartphones if they need a little help jogging their memories!

Personal Histories

This activity enables you to foster trust by giving members an opportunity to demonstrate vulnerability in a low-risk way.

Materials

None

Instructions

Go around the group and have everyone answer four questions about themselves:

- Where did you grow up?

- How many siblings do you have and where do you fall in the birth order?

- What was the most difficult or important challenge of your childhood?

- What is your best memory from childhood?

Set the tone to focus on positive outcomes from difficult situations. Otherwise, this exercise could devolve into a series of “how my childhood was worse than yours” stories. It could also bring out some very negative emotions if not handled well by the leader.

Debrief

During the debrief, ask the following question:

What did you learn about others that you didn't know?

Variations

Other questions could be used here, as long as they call for moderate vulnerability. For instance, “What is your favorite food?” wouldn't work because it involves virtually no vulnerability. Likewise, “How do you feel about your mother?” also doesn't work — in this case, because it could be too invasive.

Inquiring Minds Want to Know

This exercise gives team members the chance to uncover something unusual or intriguing about each other.

Materials

Flip chart paper/whiteboard (or “web meeting” equivalent)

Instructions

-

Ask each person in the room to pick two questions from the following list (displayed on a flip chart) that they would like to ask someone:

- If you could do anything, what profession (other than your own) would you like to do? Why?

- What profession would you definitely not like to do? Why?

- What is your favorite word? What is your least favorite word? Why?

- What is a funny memory that you have from your childhood?

- What are four words that your best friend or partner would use to describe you?

- What do you think is one of the first things that people (at work) notice about you?

- If you could be a rock star, an actor, or a celebrity, who would you be? Why?

- Ask each person to pair up with someone he or she doesn't know very well.

- Have each person “interview” his or her partner using the two questions previously selected.

- Ask each person to introduce his or her partner and share that person's answers to the interview questions.

Variation

Instead of providing a list of questions in Step 1, ask team members to write down two creative or interesting questions they'd like to ask someone. Use one or two of the questions in the list as an example.

What I Bring to the Team

This exercise is an opportunity for team members to recognize and disclose their own strengths and areas for improvement. It can also be an opportunity for the team leader or other team members to give each other positive feedback.

Materials

None

Instructions

-

Ask each person to reflect on why he or she was chosen for his or her position on the team (strengths, experience, and so on).

Specifically, ask each person to list the following:

- One or two things that he or she is really good at

- One or two things that he or she needs to work on or that can be a blind spot

- Ask each person to reveal his or her answers.

Variations

- Have the team leader provide feedback to each person in front of the group, commenting on strengths only. The team leader should share one or two specific things that he or she thinks makes the person a good fit for the position or a unique, important quality that he or she brings to the team.

- If appropriate, and if time allows, encourage others in the room to comment on what they see as the strengths of each person.

- Give each person a sheet of flip chart paper and ask him or her to draw a symbol that represents his or her answers. For instance, an employee who views her strength as being able to multitask might draw an octopus. Someone who views his strength as having global experience might draw a picture of planet Earth.

Scramble

In this frantic activity, team members simultaneously strategize, gather, and summarize information about each other. Afterward, they present their findings to the team. (Note that this activity isn't suitable for virtual teams.) Be sure to let team members know this activity will be chaotic, and to watch the time carefully.

Materials

None

Instructions

- Divide the team into groups of three to nine participants.

-

Give each group a topic. (Make sure you have enough topics for all groups.)

Topics may be work related (for example, pertaining to college degrees earned, languages spoken, or previous employers) or non–work related (for example, pertaining to pets, birthplace, last vacation destination, hobbies, and so on).

- Give the groups three minutes to determine how they'll gather the information for their topic from all the people in the room.

-

Give the groups three minutes to gather all the information for their topics.

This happens simultaneously for all groups.

- Give the groups three minutes to summarize the data they collected.

- Give each group one minute to present their findings to the whole team.

Debrief

During the debrief session, try asking the following questions:

- How did you accomplish your goals during each phase?

- Did you adjust your strategy during the activity? How?

- During which phase did you feel most rushed? Why?

- How does that relate to how you approach work? In other words, when do you feel most rushed or under pressure?

Variation

Give the teams an extra minute or two in the summarizing phase to record their findings on a flip chart. Then, instead of making a presentation, have them post their findings on the wall. Encourage folks to walk around the “gallery” to view the findings.

Heads or Tails

In this icebreaker activity, members tell an anecdote about themselves. The anecdote can be true or untrue. This activity gives members an opportunity to learn some interesting facts about each other.

Materials

- A coin

- A paper cup

Instructions

- Have the team sit around a table so everyone can see each other.

- The first participant starts by placing the coin face up or face down under the cup so no one can see it.

- If the participant placed the coin face up, he or she must tell a true story about himself or herself; if the participant placed it face down, he or she must tell a story that is untrue.

- The group tries to guess whether the story is true or untrue.

- The participant lifts the cup to reveal the answer.

- Repeat until all members have had the chance to tell their stories.

Debrief

During the debrief session, try asking the following questions:

- How did you decide whether the story was true or untrue?

- If you made up a story, where did it come from?

- What's the value of getting to know each other outside of a purely work-related setting?

Variations

- Limit stories to work situations.

- Have participants make a statement about themselves rather than tell a story — for example, “I've been to every continent at least once.”

- Make it a bit competitive. Break the team into two groups. Have a member from each team share his or her story or statement, and have the other team confer to guess if it was true or untrue. Take turns sharing stories and guessing whether they're true. The team with the most correct answers after everyone shares their story wins a small prize.

- For virtual teams on the phone, have the member reveal his or her correct answer without using the coin and cup.

Rainbow of Diversity

This exercise helps members recognize and appreciate what's going right among them.

Materials

A different-colored crayon for each participant. (A large box of 48 works well.)

Instructions

- Give a crayon to each person.

-

Have each person pair up with someone whose crayon is close to his or her own color.

Don't let team members get too worried about the “correct” or closest color.

- Give everyone two minutes to discover what strengths they have in common that contribute to the success of the group.

-

Have them pair up again, this time with someone whose crayon is very different from their own color.

Again, don't let them get too hung up on finding the exact opposite.

- Give them four minutes to identify what each others’ strengths are and how they can learn from and appreciate those different skills or abilities.

- Have all the participants get together in a circle, standing next to colors that are most like their own; ask the debriefing questions (see the next section) while in the circle.

Debrief

During the debrief session, ask the following questions:

- What did you learn about the person with a color similar to yours?

- What did you learn about the person with a color different from yours?

- What does this circle say about our team?

Hit Me with Your Best Shot: Conducting a High-Impact Team Workshop

Picture this: You've just been asked to lead a major, high-profile, long-term project that requires your staff to work closely with employees from other departments and outside consultants. Of course, you could try to engage these myriad dynamic forces via e-mail and teleconferences, but there's a better way: a high-impact team (HIT) workshop.

A HIT workshop is designed to align and engage your employees to work toward a common goal. It involves bringing together all the key players, face-to-face if possible, for a one-and-a-half-day gathering. This highly interactive and engaging workshop mixes team dynamics analysis, process improvement, communication networks, group problem solving, action planning, and of course, fun!

To conduct a HIT workshop, follow these steps:

-

Clarify the current state of the business and/or project (that is, “Where we are now?”).

This step involves a thorough discussion of the key metrics of the business and/or project.

-

Have breakout discussions on where the business or project should go (that is, “Where are we going?”).

This phase should weave in discussion of current impediments and strengths.

-

Construct a high-performing action plan (that is, “How we will get there?”).

This action plan, along with an implementation strategy, should be created and agreed to by participants in the workshop.

Throughout the workshop, apply team-building activities liberally. Opt for activities that are focused on building the competencies required of engaged teams.

A well-structured process like the one in a HIT workshop pays countless dividends, including the following:

- Improved communications, which expedites work and work processes

- A common sense of direction, established through mutual goals and expectations

- The ability to hit the ground running and avoid costly startup mistakes

- Practice working together in a controlled setting

- Group interaction, and getting to know one another

- A level of comfort and joint ownership of solving a common problem

All teams must go through the forming, storming, and norming stages to get to the performing stage. If you think you've skipped a stage, look a little more closely. Teams rarely skip stages. The speed at which a team progresses through these stages will depend on the size of the change, the experience of the team members, the experience of the leader, and how engaged the team is as a whole. Strong, engaged teams will find ways to accelerate through the stages.

All teams must go through the forming, storming, and norming stages to get to the performing stage. If you think you've skipped a stage, look a little more closely. Teams rarely skip stages. The speed at which a team progresses through these stages will depend on the size of the change, the experience of the team members, the experience of the leader, and how engaged the team is as a whole. Strong, engaged teams will find ways to accelerate through the stages. To expedite the forming stage, the team leader must focus on providing direction and structure and building relationships and trust. This kickoff process involves the following:

To expedite the forming stage, the team leader must focus on providing direction and structure and building relationships and trust. This kickoff process involves the following: Experience shows that an individual or team that develops its own action plan is overwhelmingly more likely to follow through on the actions than when the action plan is assigned.

Experience shows that an individual or team that develops its own action plan is overwhelmingly more likely to follow through on the actions than when the action plan is assigned.